Tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) and prosthesis insertion has become the technique of choice for voice and speech restoration in patients undergoing total laryngectomy.

Enlargement of the tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) may lead to leakage and aspiration of liquids causing severe complications such as aspiration pneumonia, vascular breakdown and even death.1,2

We report a case of a salvage reconstruction with a gastro-omental flap in a large persistent TEF in a 71 year old man in whom conservative treatment and the interposition of a muscular flap had failed and whose local and general physical condition made the resolution of the fistula particularly difficult. The application of this free flap in the context of a TEF has not been described to date.

The patient had been treated eight years before for supraglotic squamous carcinoma with total laryngectomy and bilateral radical modified neck dissection therapy with the intraoperative insertion trough a tracheoesophageal puncture (TEP) of a prosthesis (Provox) that allowed a successfully speech rehabilitation. Postoperative Radiation therapy was performed.

During the patient follow-up at least two hospitalization episodes for broncospirative pneumonia occurred due to a widening of the tracheoesophageal puncture. After some initial failed attempts to solve the problem with either removing temporary the prosthesis or placing a silastic lamina to close leakage zones between the Provox and the fistula, a silicone button was placed into the fistula with a rigid bronchoscope. It seemed that a definitive closure of the tracheoesophageal communication was achieved but the silicone button was also lost twice over the next few years.

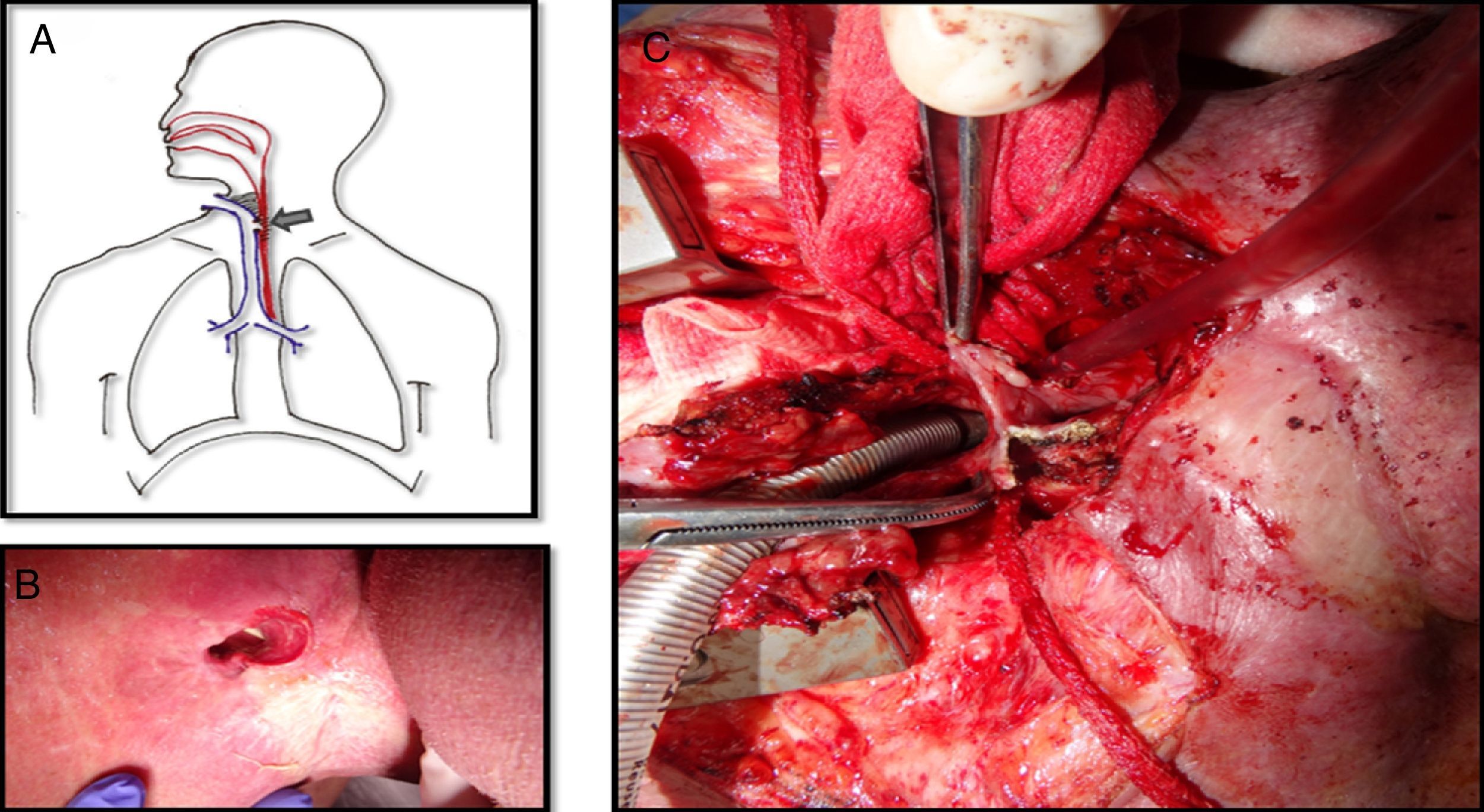

The tracheoesophageal fistula presented by this patient eight years after the primary surgery was about 5×2cm, extending from the level of the tracheostoma to below it, affecting the substomatic trachea as well (Fig. 1A and B). Due to the large size of the fistula the exchange of the silicone button was impossible and it couldn’t be closed either with rigid bronchoscopy or esophagoscopy. Surgical correction with the interposition of a pectoral flap between the trachea and the esophagus was unsuccessfully attempted since the fistula rapidly recurred over few weeks.

A. Picture showing the tracheoesophageal fistula with lot of fibrosis around it. B. The nasogastric tube is visualized through the tracheostoma which confirms a large fistula at this level. C. The trachea is detached from the esophagus. The posterior wall of the trachea has already been removed because the tissue was necrotic. The defect on the anterior wall of the esophagus is visualized.

Finally a gastro-omental flap was performed to try to solve the problem. Surgery was carried out by a multidisciplinary team integrated by otorhinolaryngologists, thoracic and plastics surgeons.

Patient obesity made it difficult to achieve good visualization of the fistula with a cervical approach so a partial upper sternotomy with unilateral J-shaped extension to the right through the third intercostal space was performed. Afterwards, the trachea was detached from the esophagus and the anterior wall of the esophagus and the posterior aspect of the trachea were debrided (Fig. 1C).

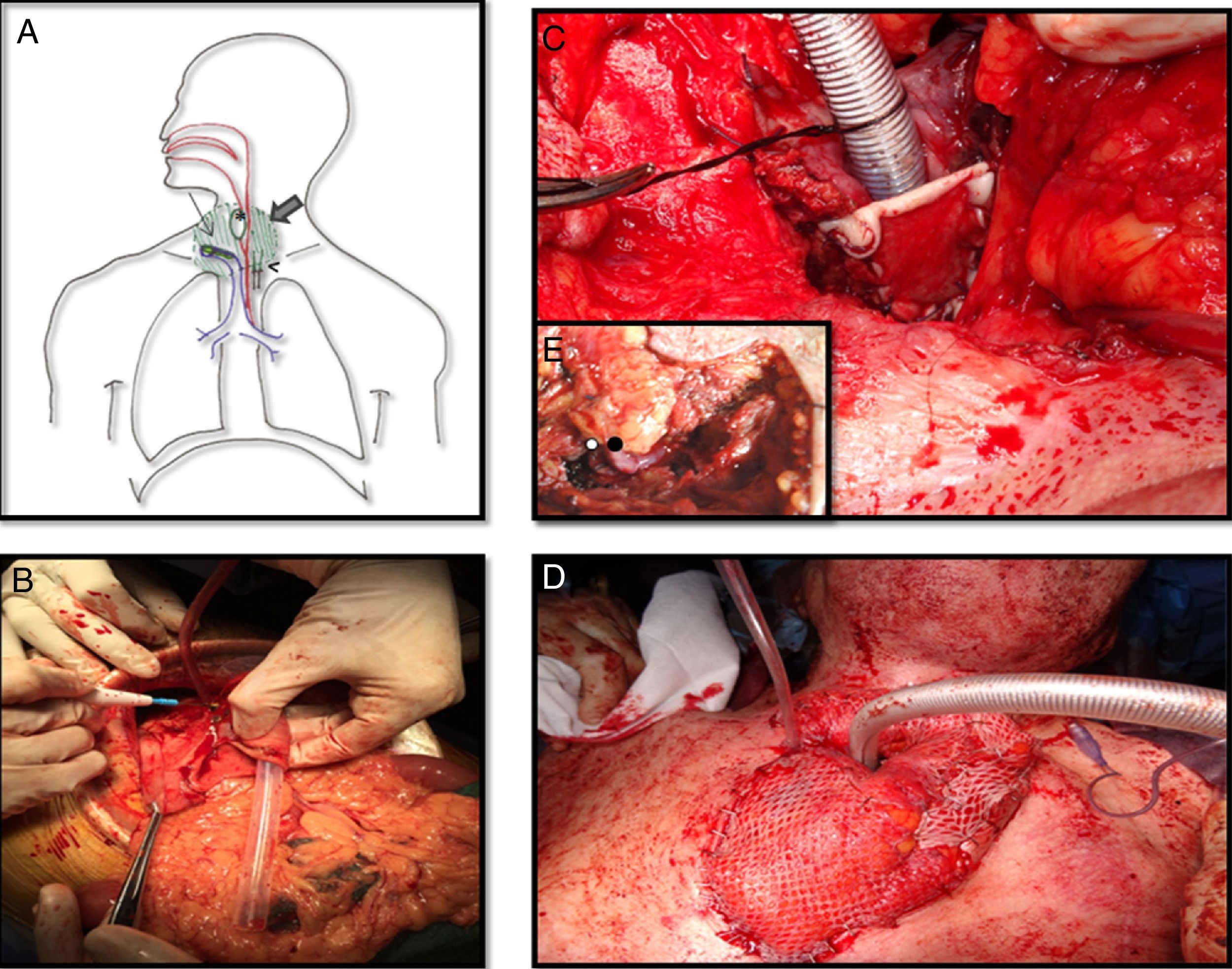

Meanwhile a second team raised the gastro-omental flap, a composite flap which includes a portion of the greater curvature of the stomach, which was harvested in an elliptic shape just a bit larger than the esophagus, and greater omentum pediculated on the right gastroepiploic vessels (Fig. 2B).

A. Schematic view of the reconstruction. Large arrow is pointing out the epiplon surrounding the tracheostoma and the esophagus. Thin arrow is on the skin graft covering the posterior side of the trachea. Head of arrow shows de microvascular anastomosis and finally de asterisk is into the stomach patch that makes up the anterior esophagus. B. Gastro-omental flap with its omentum portion below and the shaping of the stomach patch. C. At the tracheostoma level, the posterior wall of the trachea is formed by a skin graft. The omentum which will be placed around the tracheostoma and behind the skin graft will nourish it. D. The cervical trachea was moved and the new tracheal stoma was placed just 2cm below it was before. Surrounding it the omentum covered by skin grafts. E. Vascular anastomosis under microscope between the right gastroepiploic vessels and the mammary internal ones at the third intercostal space. The white spot is on the arterial anastomosis and the black spot on the venous anastomosis.

The inset procedure of the flap into the neck was carried out before performing the vessels anastomosis. The stomach patch was fashioned to rebuild the anterior esophagus wall and the omentum was placed around the tracheostoma and between the trachea and the esophagus. In order to avoid a lower mediastinal trachesotomy with high risk of further complications due to compression of the great vessels, tracheal length was preserved. We achieved it by conserving all cartilaginous rings and only debriding the posterior membranous trachea which was in contact with the esophagus. Then a split-thickness skin graft from the tight was used to resurface the posterior wall of the trachea on the tracheostoma level as well as to prevent the airway obstruction by the omentum. Its epidermal side was stitched to the posterior edges of the trachea and its dermal face was in contact with the surrounding omentum so that it could nourish it (Fig. 2C). Finally a microsurgery anastomosis between the internal mammary vessels and the gastroepiploic ones was performed without vein graft requirement. The omentum placed around the tracheostoma was covered by skin grafts and the sternotomy was left open to avoid the compression of the flap (Fig. 2D and E).

During the first three days of the postoperative period a nasogastric tube was used for stomach aspiration to protect the stomach suture. Afterwards on the fourth postoperative day it was used for patient feeding. Post-operative evaluation with radiologic barium swallow test ten days after surgery and with computerized scanner visualization evidenced the patency of the digestive tract and the absence of fistula. Patient discharge occurred 25 days after surgery and the nasogastric tube was removed when oral intake was well tolerated on the 45th post-operative day. Over the next sixteen months of follow-up the omentum atrophied significantly improving neck appearance and the patient continued tolerating oral diet without need to endoscopic balloon dilatation.

The initial management of TEF usually involves a combination of various conservative measures such as changes in the size of the prosthesis, temporary prosthesis withdrawal, TEP site injection, suture placement around the puncture or the placement of silicone button prostheses in order to close the fistula.3

However, in patients with a high risk of wound breakdown, toxicity by radiotherapy, high levels of contamination at the local site and with previous flaps failed, as wells as in obese patients in whom breathing and coughing may increase instability, we believe that the insertion of a gastro-omental free flap is a good alternative.4–7

The gastric mucosa can be easily customized to the defect without adding significant weight (this is the main disadvantage of muscle flaps, which present excessive bulking). Furthermore, the long omental pedicle allows the creation of the anastomosis to the extra cervical vessels outside the contaminated and radiated area. The omentum can fill all dead spaces and also provides highly vascular tissue rich in growth factors and progenitor cells which help the injured tissue to heal and also protect the anastomosis of the defect and exposed vessels. Although there is some concern about the peptic ulceration of the recipient site, mucus production from the transferred stomach mucosa and atrophy of the denervated gastric glands makes this complication fairly rare. In addition, intensive therapy with proton-pump inhibitors is used for the first three months before atrophy of gland occurs. Besides, the greater antrum, which is the portion of stomach harvested, is sparsely populated by gastric parietal cells.8–10

Please cite this article as: Viñals Viñals JM, Tarrús Bozal P, Serra-Mestre JM, Bermejo Segú O, Nogués Orpí J. Reparación de fístula traqueoesofágica recurrente con colgajo gastro-omental libre en un paciente irradiado. Cir Esp. 2017;95:615–617.