Castleman's disease (CD) also known as angiofollicular mediastinal lymph node hyperplasia, is a rare lymphatic disorder, described by Benjamin Castleman in 1954.1 Two types are differentiated: unicentric (localised lymph node involvement) or multicentric (multifocal or generalised).2 Unicentric CD is usually asymptomatic or has symptoms due to local compression (mediastinal invasion/superior vena cava syndrome); multicentric CD is dominated by non-specific symptoms such as fever, fatigue, night sweats or weight loss.3,4 Clinical significance lies in the associated neoplastic potential, with the possibility of developing lymphoproliferative syndromes (Hodgkin's or extranodal B-cell lymphoma, follicular dendritic cell sarcoma or Kaposi's sarcoma).5,6 The differential diagnosis should be established mainly with lung cancer, without ruling out other disease such as infections, sarcoidosis or inflammatory pseudotumour.1,3,5 Three histopathological patterns can be distinguished: hyaline vascular (the most common with a predominance of unicentric disease); plasma cell (multicentric) and mixed.1 Biopsy or excision of the lesion is necessary to make the diagnosis and rule out malignancy, with the treatment of choice being complete surgical resection in well-delimited localised unicentric lesions; without the need for multimodal treatment and with rare local recurrence.3

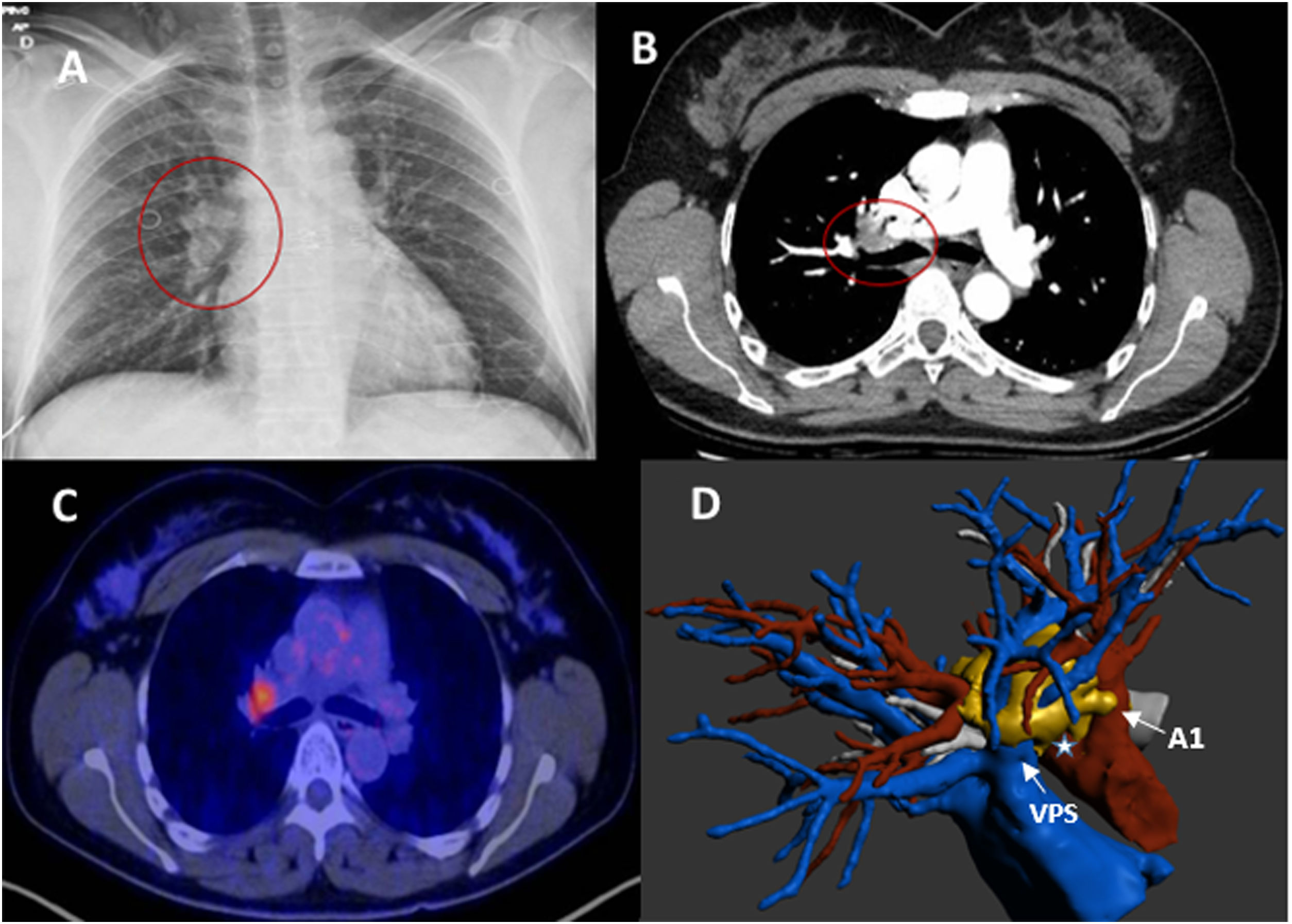

We present a 45-year-old female smoker (20cig/day), coincidentally diagnosed with a right hilar lesion on chest X-ray (Fig. 1A). CT scan showed a right hilar nodular lesion (28 mm) with no other findings. The lesion extensively touched and partially involved the superior lobar arteries, superior pulmonary vein, and right main bronchus, suggestive of malignancy (Fig.1B). 18FDG-PET/CT showed right hilar hypercapitation (SUVmax 5.8), with no pathological adenopathies (Fig. 1C). Spirometry (FEV1 and DLCO) was normal. EBUS was performed for histological affiliation with negative FNA for malignancy, and the decision was taken in a multidisciplinary committee for diagnostic-therapeutic surgery. 3D reconstruction was very useful in preoperative planning, showing the precise location of the lesion (1D). Exploratory VATS was started, and multiple adhesions were observed with conversion to lateral thoracotomy. A hilar mass encompassing the pulmonary vein and right superior lobar arteries was observed without histopathological diagnosis after intraoperative biopsy. Given the feasibility of complete resection, a right upper lobectomy with systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy was performed. The anatomopathological diagnosis confirmed the presence of unicentric hyaline vascular Castleman's disease (Fig.2A and B) with anthracotic lymphadenopathy and sinus histiocytosis, and the immunohistochemical study was negative for HHV-8 and EBV-LMP1. The patient made satisfactory progress and was discharged from hospital on the third postoperative day, with no evidence of recurrence after 1 year of follow-up.

(A) Chest X-ray in PA projection with increased right hilar density. (B) Axial CT scan with right hilar lesion encompassing vascular branches and in contact with the right main bronchus. (C) PET/CT image with pathological hyperenhancement in the right hilar region. (D) reconstruction showing lesion encompassing right superior pulmonary vein, in close contact with mediastinal arterial branch (A1) and truncus arteriosus (*). PA, posteroanterior; CT, computed tomography; PET/CT, positron emission tomography.

Castleman's disease, hyaline vascular type. (A) HE stain (20×). Atrophic follicle with expansion of the mantle zone showing the "onion layer" pattern and penetrating hyalinised vessels (lollipop). (B) HE stain (0.3×). Panoramic view. Enlarged lymph node with follicular hyperplasia, hyalinised atrophic germinal centres, and expansion of the mantle zone. HE, haematoxylin-eosin.

The aetiology is unclear, with a causal relationship in multicentric cases with infection by human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), as well as association with HIV infection, Kaposi's sarcoma, lymphoma or POEMS syndrome (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal protein, skin changes).1,3 Cytopenias, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinaemia or hepatic and/or renal dysfunction may occur secondary to cytokine release (IL-6, IL-1 or tumour necrosis factor alpha).3,7 With no gender predilection, it can occur at any age, but is rare in children and predominant between 30 and 40 years in unicentric CD.3 The typical radiological finding is a solitary, well-demarcated incidental mass in the thorax (tracheobronchopulmonary lymphatic region), homo- or heterogeneous, sometimes with necrosis or degeneration (large size).3,6 They also appear as hypervascularised lesions with adhesions to adjacent structures or mediastinum.8 The most frequent sites are cervical, axillary, mediastinal and abdominal, with few cases described at intrapulmonary or hilar level.2,3 Other infrequent locations are nasopharynx, mesentery, retroperitoneum, chest wall or extremities.3,6 The value of 18FDG-PET/TC is controversial, and it is not possible to differentiate between CD and malignancy, with cases described with SUVmax between 1.4 and 7.4 in lung involvement. Given its malignant potential, biopsy should be considered in the presence of elevated SUVs (rare in multicentric disease), or hypermetabolism in large lymph node conglomerates.8

Videothoracoscopy is considered a feasible technique for the diagnosis and treatment of selected unicentric cases; bleeding or firm adhesions of the mass to neighbouring structures are the main reasons for conversion to thoracotomy.9 There is the possibility of enucleation of well-demarcated lesions, avoiding major lung resection.2,4 Talat et al. in their systematic review (n = 404) described a surgical or debulky resection rate of 77%, more frequent in unicentric (94.3%) than multicentric (38.9%) CD, with longer overall survival in unicentric (95.3%) vs multicentric disease (61.1%) and longer disease-free interval at 3 and 5 years in unicentric disease. In unresectable lesions, residual tumour, or inoperable patients, neo or adjuvant therapies3–5 such as adjuvant radiotherapy have been described with satisfactory long-term results and excellent local control (25−50 Gy dose) in the chest.3,6,10 In multicentric CD, surgery is not considered a first option and is reserved for diagnostic purposes. Treatment will usually be systemic based on gluocorticoids, chemotherapy or anti-IL-6 antibodies (rituximab, tocilizumab, or siltuximab) given the elevated expression of IL-6, with a worse prognosis than unicentric disease.3

With our case we wish to highlight the similarity of unicentric CD with lung cancer, emphasising the importance of establishing a differential diagnosis of this disease with other entities. Preoperative diagnosis is usually complex due to the nonspecific clinical and radiological manifestations. Surgical resection of the lesion and postoperative histopathological study is required to reach a diagnosis of certainty.

Please cite this article as: Carrasco Fuentes G, Sevilla López S, Sabio González A, Bravo Cerro AJ. Enfermedad de Castleman unicéntrica simulando un cáncer de pulmón hiliar. Cir Esp. 2023;101:298–300.