Incisional hernia after abdominal surgery has an incidence between 5% and 15%.1 Pregnancy after abdominal surgery is an independent risk factor for the development of an incisional hernia,2 and herniation of the gravid uterus through an incisional hernia is very rare.3

Complications associated with the appearance of this condition during pregnancy as a possible incarceration or strangulation are a serious obstetric problem with important consequences for both the mother and the fetus.

Due to its low incidence, there is no consensus regarding management, which requires individualized treatment.4 In uncomplicated hernias, initial conservative management with abdominal wall repair either intrapartum or in a second stage seems to be a good option.5

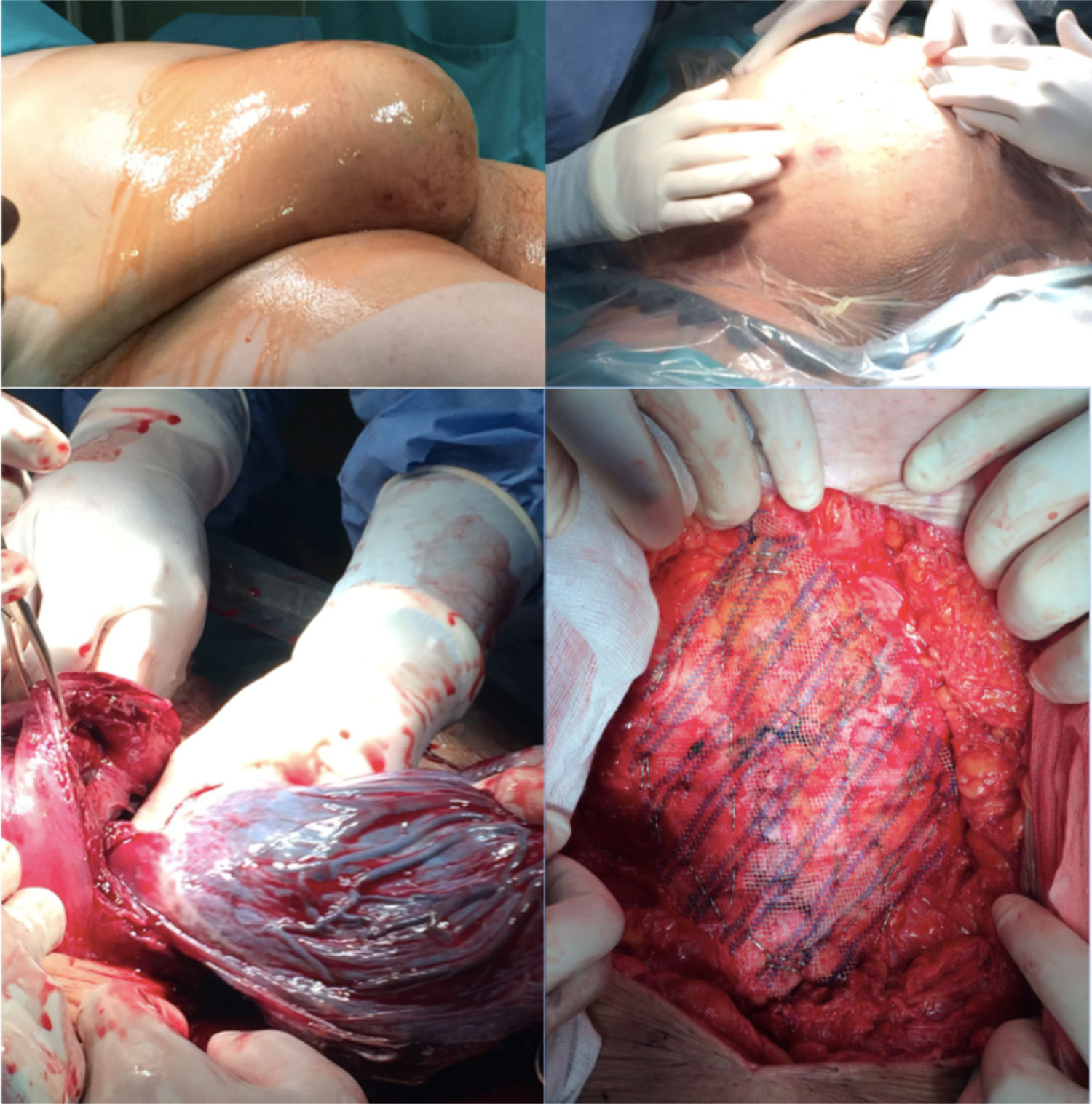

We present a case of incisional hernia of a gravid uterus in a 34-year-old pregnant patient, who was referred to our unit at week 30+1 for suspected uterine herniation. The patient had a history of a previous cesarean section with an infraumbilical midline laparotomy and grade III obesity (weight: 135.4kg and BMI: 49.1) and was being monitored for her high risk of gestational diabetes.

The first trimester of pregnancy passed without incident, but in week 20 of gestation the patient experienced hypogastric pain that prevented her from sitting. During examination, an irreducible tumor was detected at the level of the cesarean section scar. An ultrasound of the abdomen during an office visit revealed a uterine hernia, with no alterations in the fetus.

At week 30+1, our team was contacted for evaluation. During the examination, we observed an abdomen corresponding to the weeks of gestation and an incisional hernia through the infraumbilical scar, which became more evident with Valsalva maneuvers. The presence of uterine herniation was confirmed by follow-up ultrasound. Given the complexity of the case, we opted for a multidisciplinary approach with the gynecology team, proposing elective cesarean section, tubal ligation at the express request of the patient, and incisional hernia repair during the same operation, scheduled for week 38 of pregnancy.

Access was created through the previous incision, and the hernia sac was opened to access the uterus placed in forced anteversion position, which required manipulation to visualize the lower segment and conduct hysterotomy using a Kerr incision (transverse incision of the lower segment). The cesarean section was uneventful, giving birth to a live female fetus in transverse position; bilateral tubal occlusion was performed by simple ligation and partial salpingectomy. In the second stage of surgery, an M4W2 incisional hernia was observed (European Hernia Surgery classification) with an aponeurotic defect measuring 15cm in length and 7cm wide. Given the laxity of the abdominal wall, a repair was performed with primary closure using continuous suture of a caliber 0 slow-absorbing monofilament suture material following a 4:1 ratio, placement of a 25cm×15cm polypropylene mesh onlay with a wide pore (1.5mm) and low weight (60g/m2), affixed with a double crown of non-absorbable fascia tacks and a minimum overlap of 5cm, followed by the placement of 2 subcutaneous suction drains, all of which proceeded without incident (Fig. 1). The postoperative period was favorable, and the patient was discharged on the 8th postoperative day after confirming no drain discharge.

Two years after the procedure, the patient had a follow-up office visit, at which time there was no evidence of hernia recurrence.

The incidence of incisional hernia during pregnancy is unknown, but it is very rare in Western countries.3 For this reason, there is not enough evidence about its management, so individualized management should be based on the characteristics of the mother, fetus and gestation.

The most frequent symptoms and signs are abdominal pain, vomiting and the appearance of a mass in the region of the previous scar. During examination, a palpable defect can be found in the wall with either reducible or non-reducible content and sometimes abdominal distension.5–7 To complete the study, abdominal ultrasound is usually sufficient to determine which structures are contained in the hernia sac. However, sometimes MRI is indicated when the ultrasound does not provide a clear diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis has been made, it is essential to monitor the pregnancy in order to detect uterine changes that could result in delayed intrauterine growth of the fetus. Risk factors associated with this complication have been described, including advanced age, polyhydramnios and multiple gestation.

Although the literature includes approaches during the first months of gestation, both anesthesia and surgery can lead to an increased risk of complications for the mother and the fetus. Therefore, most authors advocate repair during elective cesarean section or in a second phase. In the case of complications, emergency surgery is mandatory. Uterine strangulation in full-term pregnancies is an indication for urgent laparotomy, cesarean section and wall repair in the same operation. When the complication occurs in the early stages of pregnancy, urgent repair of the defect is indicated, assessing fetal viability and continuing gestation if possible.5,7

FundingThis publication has not required any type of funding.

Please cite this article as: Camacho Marente V, Olivares Oliver C, Marchal Santiago A, Martin Cartes JA, Bustos Jimenez M. Eventración uterina en paciente gestante. Cir Esp. 2020;98:303–305.