An accessory spleen is a relatively common defect that occurs in 10–30% of the population, but it is often misdiagnosed or unrecognized due to its frequent small size.1 It originates because of fusing failure of the splenic tissue as the spleen migrates from the midline to the upper left quadrant during embryological development. This phenomenon may happen anywhere along the spleen's abdominal path, but it is frequently set in the hilum of the spleen, the tail of the pancreas or the gastrosplenic and splenorenal ligaments.2 Occasionally other rare locations have been described,1–4 such as the case we present below.

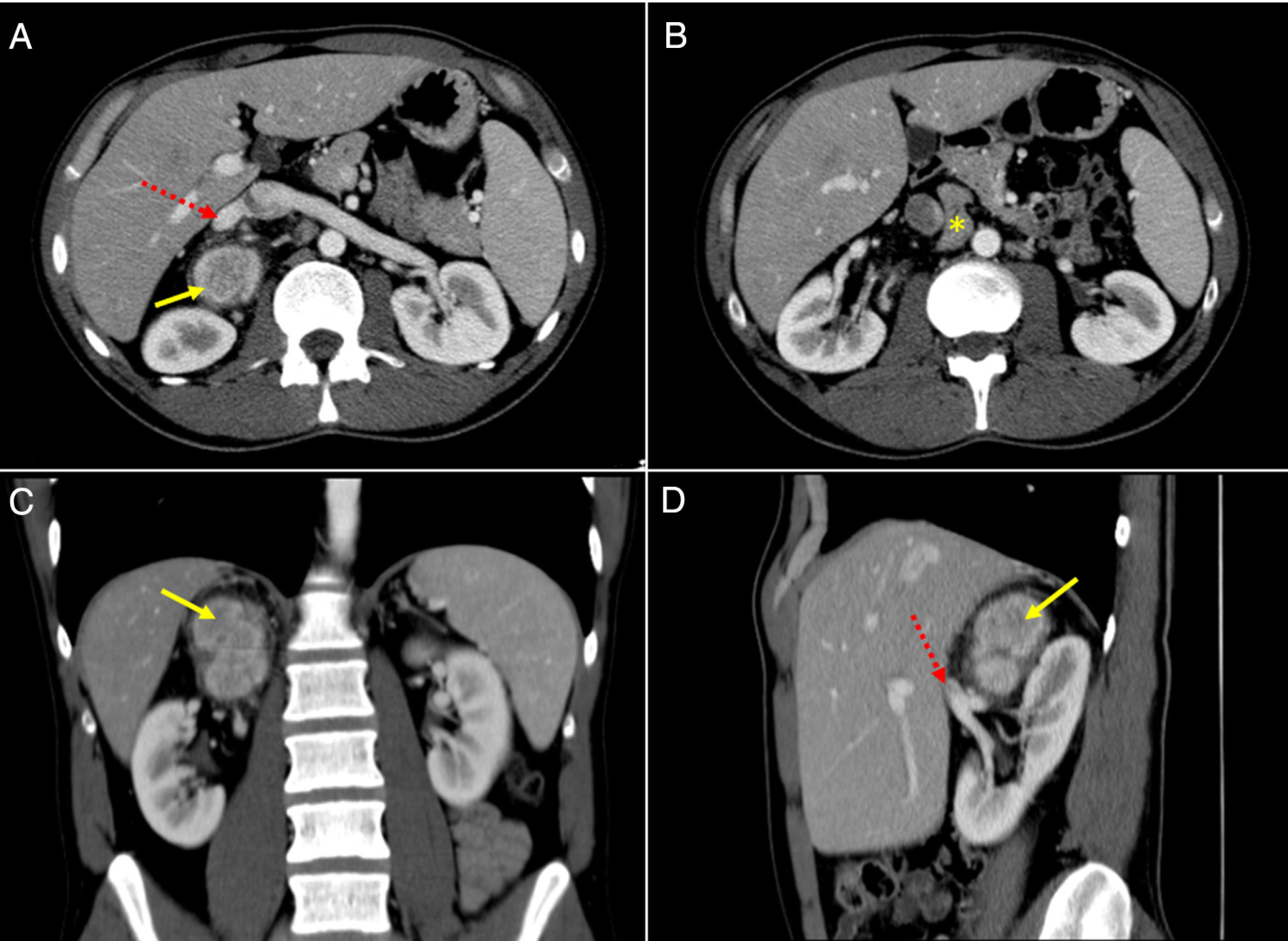

A 34-year-old male patient with unremarkable past medical history was admitted to our institution for an intermittent, non-specific, right low back pain. Suspecting a typical renal colic, an ultrasound (US) was performed which identified a 63mm×45mm×34mm right adrenal mass. In order to confirm the diagnosis, a computed tomography (CT) scan and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were conducted. The CT scan confirmed the US findings, showing a 32mm×41mm ovoid, relatively well-defined, heterogeneous mass, with intense contrast-enhancement (114 Hounsfield units) in the arterial phase and a wash-out pattern with late registrations lower than 50%. In addition, a 32mm irregular adenopathy in the retroperitoneum was described next to the right adrenal gland (Fig. 1). In the MRI, the lesion was hypointense in the T1-weighted image and hyperintense in the T2 signal. Aiming to typify the adrenal incidentaloma, endocrinological studies were performed. Nugent test, urine catecholamines and seric aldosterone, cortisol, DHEA, testosterone and androstenedione were all within normal limits. Since a non-functional malignant neoplasm could not be ruled out, a laparoscopic exploration was arranged.

CT scan (a–b, Axial view; c, Coronal view; d, Sagittal view), showing a heterogeneous mass in the right adrenal gland topography, with intense contrast enhancement (yellow arrow) and close to the right renal vein in its origin from inferior vena cava (discontinuous red arrow). In a lower axial view, an irregular adenopathy was found in the retroperitoneum (yellow asterisk), between the aorta and vena cava, next to the lower margin of the tumor.

The patient was placed in left lateral decubitus position and an anterior laparoscopic approach was performed. A great mass with surrounding retroperitoneal adenopathies was found, with dense adhesions to parietal peritoneum and nearby structures. Laparoscopic resection was not possible due to the apparent absence of a clear cleavage plane between the mass and inferior vena cava and renal vessels. Conversion to median laparotomy was then conducted, and the adrenalectomy was performed effectively with regional lymphadenectomy. No postoperative complications were registered, and the patient was discharged on the fourth postoperative day.

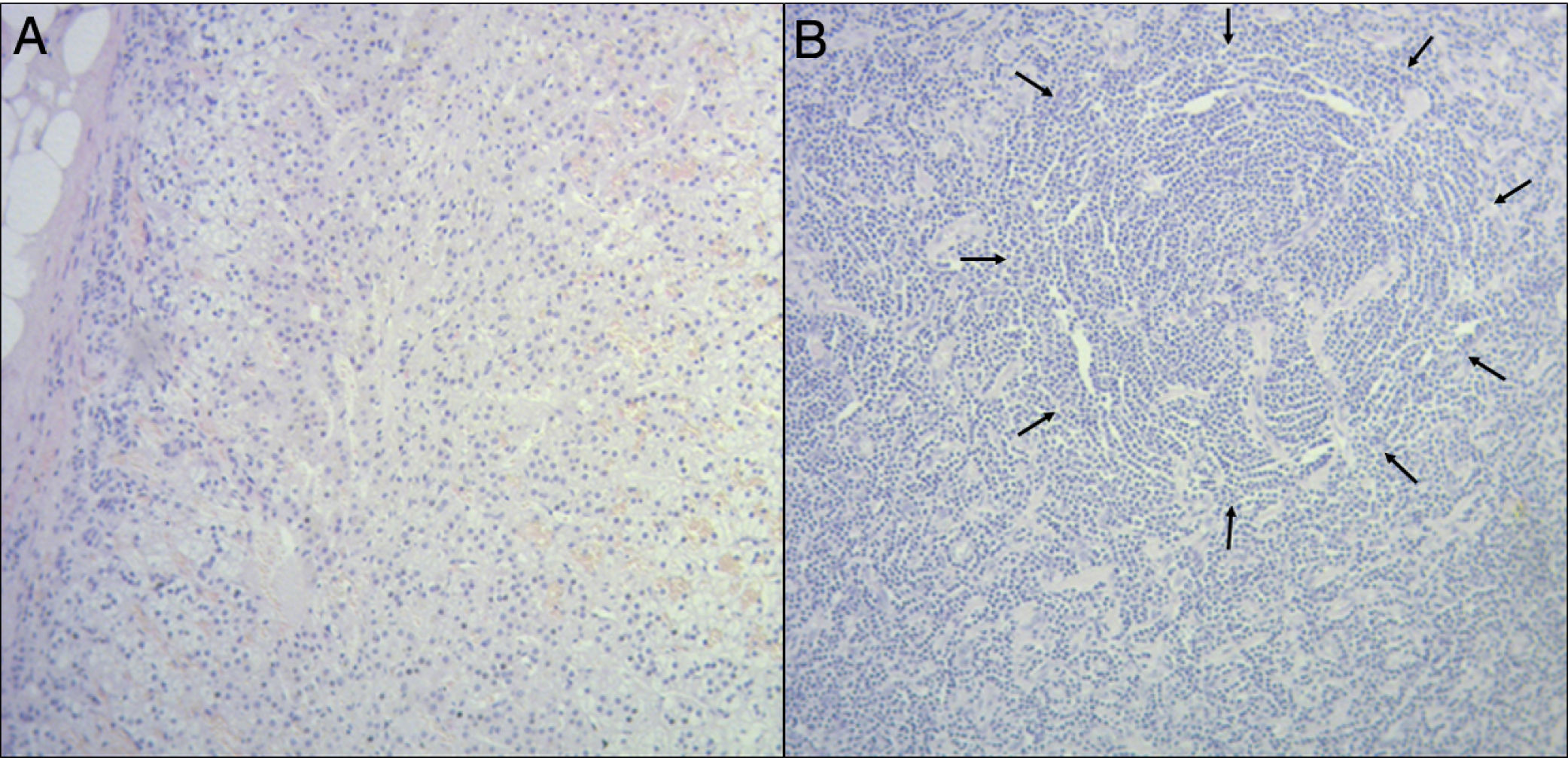

The anatomopathological exam revealed a 110 grams and 9cm×7cm×4cm long surgical piece, which contained a nodular mass of whitish coloration, soft-elastic consistency and well-defined edges that measured 5cm×3.5cm×3cm. The histological examination of the mass unexpectedly revealed spleen tissue, with normal histoarchitecture (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical analyses were carried out to confirm the diagnosis: they demonstrated positive CD20 in germinal center, positive CD3 in periarteriolar sheath and surrounding the follicles, and positive Ki67 in B-cells of the germinal centers, all of these consistent with the original finding. Four lymph nodes were found in the surrounding adipose tissue, showing no antigenic stimulation. An accessory spleen was then confirmed and no further treatments were conducted.

Accessory spleens usually remain as an isolated asymptomatic anomaly and its clinical significance appears when mistaken for an enlarged lymph node or neoplasm.1 Therefore, an accurate interpretation of the preoperative findings could be the key to avoid unnecessary surgery. However, no CT/MRI hallmark or criteria for diagnosing accessory spleens has been described, to the best of our knowledge.5 This explains why in most of the reported cases the definitive diagnosis is reached postoperatively.1–4

For all the aforementioned reasons, we applied a typical diagnostic and treatment algorithm for an adrenal mass. Given the specific location and features of the apparent adrenal tumor, we could not exclude the possibility of malignancy. Thus, surgical exploration could not (and should not) be avoided.

Even though the anatomopathological results were unexpected, the unmistakable histoarchitecture of the spleen allows an almost definitive diagnosis with classic staining techniques. Nevertheless, we recommend performing immunohistochemical analyses in order to dismiss any possible uncertainty.

In summary, when a non-functional adrenal mass is suspected by imaging and serological tests, an accessory spleen should be considered as a possible differential diagnosis. However, we strongly recommend performing a laparoscopic exploration as long as a malignant tumor cannot be ruled out preoperatively.

Conflict of interestNone declared.