Breast cancer (BC) is the most common malignant tumor in women as a result of a combination of physical, chemical, biological and genetic factors. Most BC is sporadic, and less than 10% of cases present a family relationship, fundamentally due to alterations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Only a small number of hereditary cases can be attributed to mutations in other genes, such as p53 in Li-Fraumeni syndrome, PTEN in Cowden syndrome, MSH2 and MLH1 in Muir-Torre syndrome, ATM in ataxia telangiectasia and STK11 in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS).1

PJS is a rare disease characterized by the association of hamartomatous polyps in the digestive tract, hyperpigmented macules on the lips and oral mucosa and an increased risk for developing digestive and extradigestive neoplasms. Its hereditary pattern is autosomal dominant (AD) with a variable penetrance, and in a high percentage of cases (80%–94%) it is associated with mutations in the specific 19p13.3 locus of the LKB1/STK11 gene.2,3

PJS was first defined in 1954 by Bruwer et al.4 and it is classified in the hamartomatous polyposis group together with juvenile polyposis, hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome, Cowden syndrome and the Ruvalcava-Myrhe-Smith syndrome, and it shares a high risk of colorectal cancer.5 In PJS, there is also a high probability of neoplasia in the rest of the digestive system, and other locations at early age, most frequently breast (54%), ovarian (21%), cervical (19%) and lung (15%) cancer.5,6

This rare syndrome (1/200000 newborns), which equally affects both sexes, is usually diagnosed during childhood based on family history, presence of typical melanotic macules or problems caused by the growth of intestinal polyps that cause symptoms of invagination, obstruction or hemorrhage.

Although pigmentation can appear at any age, it is most frequent during infancy and early childhood, with melanin deposits on the lips (95%) or in the mouth (83%), and less frequently on hands, feet and periorificial locations. The majority of the clinical manifestations are gastrointestinal, although the hamartoma–adenoma–carcinoma sequence is controversial for some authors7 and it is known as the “landscape effect”. The alterations, especially in the lamina propia, can lead to epithelial cancers.8 On occasion, the initial manifestation is the appearance of a neoplasm at an early age due to the risk accumulation.

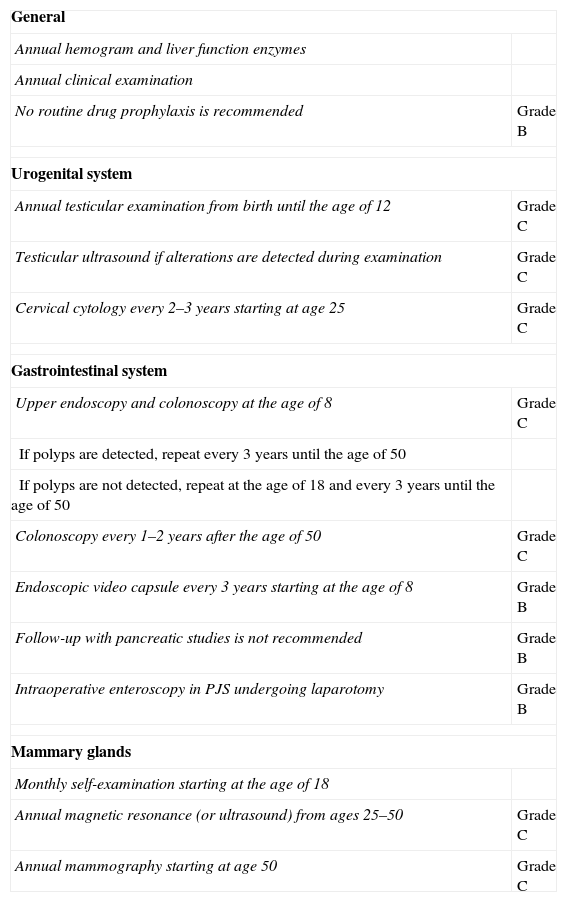

We present the case of a patient affected by BC in whom the hereditary cause was discovered incidentally. The patient is a 51-year-old Caucasian woman with a history of chronic anemia (treated with oral iron supplements) who had also undergone cholecystectomy. She reported no family history of breast cancer or any genetic alterations. At the age of 50, the patient had been diagnosed with bilateral breast carcinoma after a mammography had detected suspicious microcalcifications, which was later confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1). Bilateral mastectomy was performed along with selective biopsy of sentinel axillary lymph nodes, which was negative; immediate reconstruction was therefore performed with a Becker expander/implant. The pathology study reported the carcinoma to be a high-grade intraductal type (Van Nuys index >8) in both breasts.

Mammography, barium transit study and digestive ultrasound images: (A) diffuse microcalcifications in the right breast; (B) diffuse microcalcifications in the left breast; (C) upper GI ultrasound reveals hamartomatous polyps in the third duodenal portion (white arrow); (D) gastrointestinal tract where filling defects are observed in the proximal jejunum that represent polypoid formations (white arrow).

The patient came to the emergency room complaining of rapid onset discomfort in the right hypochondrium and nausea, with no associated fever. Blood tests showed mild hypertransaminasemia, and the study was completed with ultrasound and cholangio-MRI, providing a diagnosis of choledocholithiasis. During ERCP, numerous duodenal polyps were found as well as a choledochal calculus, which was extracted. Several gastric and duodenal polyps were removed by upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy (Fig. 1). The presence of perioral melanotic macules and the histologic confirmation of hamartomatous polyps established the diagnosis of PJS.9

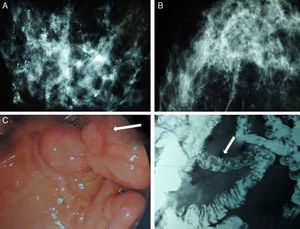

All patients diagnosed with PJS should be followed-up for life and sent for genetic counseling in accordance with the recommendations proposed by a committee of European experts that met in Mallorca in 2007, published in a consensus document (clinical guidelines) with a level of evidence of B or C.9 The objective is twofold: (1) to detect the presence of polyps with an appropriate size for endoscopic extirpation in order to avoid possible complications; and (2) to provide early cancer diagnosis.

These recommendations, shown in Table 1, require a close multidisciplinary follow-up with analyses as well as examinations of the digestive and urogenital systems, in addition to programmed breast examinations at a younger than usual age. Our patient currently continues to undergo these follow-up tests and her genetic study is pending, which could define the recommended interval for screening and checkups within her family, in order to avoid future neoplasia.

Recommendations for Testing and Follow-up in Patients Diagnosed With Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome, With Their Grades of Recommendation.

| General | |

| Annual hemogram and liver function enzymes | |

| Annual clinical examination | |

| No routine drug prophylaxis is recommended | Grade B |

| Urogenital system | |

| Annual testicular examination from birth until the age of 12 | Grade C |

| Testicular ultrasound if alterations are detected during examination | Grade C |

| Cervical cytology every 2–3 years starting at age 25 | Grade C |

| Gastrointestinal system | |

| Upper endoscopy and colonoscopy at the age of 8 | Grade C |

| If polyps are detected, repeat every 3 years until the age of 50 | |

| If polyps are not detected, repeat at the age of 18 and every 3 years until the age of 50 | |

| Colonoscopy every 1–2 years after the age of 50 | Grade C |

| Endoscopic video capsule every 3 years starting at the age of 8 | Grade B |

| Follow-up with pancreatic studies is not recommended | Grade B |

| Intraoperative enteroscopy in PJS undergoing laparotomy | Grade B |

| Mammary glands | |

| Monthly self-examination starting at the age of 18 | |

| Annual magnetic resonance (or ultrasound) from ages 25–50 | Grade C |

| Annual mammography starting at age 50 | Grade C |

Taken from AD Beggs et al.9

PJS, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Please cite this article as: Lorenzo Liñán MÁ, Lorenzo Campos M, Motos Micó J, Martínez Pérez C, Gumbau Puchol V. Cáncer de mama bilateral y síndrome de Peutz-Jeghers. Cir Esp. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2012.05.025