The growing epidemic of obesity and the increase in weight loss surgery has led to a resurgence of interest in biliary reflux because anatomical alterations may be refluxogenic.

HIDA scan is the least invasive scan with good patient tolerability, sensitivity and reproducibility for the diagnosis of biliary reflux.

Patients with more advanced oesophageal lesions have a higher degree of duodenal reflux. It has been shown in animal models and in vitro that there is more Barrett's and dysplasia with duodenal reflux.

There are two cases of post-OAGB malignancy reported in 20 years, both without correlation with a biliary aetiology, so the carcinogenic risk probably remains theoretical.

Prospective trials on OAGB should include endoscopy preoperatively and at 5-year intervals, to have data on the real effects of bile exposure on the gastric reservoir and oesophagus.

La creciente epidemia de obesidad y el aumento de las intervenciones quirúrgicas para la pérdida de peso, ha hecho resurgir el interés por el reflujo biliar porque estas alteraciones anatómicas pueden ser refluxógenas.

La gammagrafía HIDA es la exploración menos invasiva con buena tolerabilidad para el paciente, sensibilidad y reproducibilidad para el diagnóstico del reflujo biliar.

Los pacientes con lesiones esofágicas más avanzadas tienen un mayor grado de reflujo duodenal. Se ha demostrado en modelo animal e in vitro que hay más Barret y displasia con reflujo duodenal.

Hay dos casos de malignidad post-OAGB notificados en 20 años, ambos sin correlación con una etiología biliar, por lo que probablemente el riesgo carcinogénico siga siendo teórico.

Ensayos prospectivos sobre OAGB deben incluir endoscopia preoperatoria y a intervalos de 5 años, para disponer de datos sobre los efectos reales de la exposición a la bilis en el reservorio gástrico y el esófago.

The growing epidemic of obesity and the increase in weight loss surgery have led to a resurgence of interest in biliary reflux, which is becoming an increasingly common area of study.1,2

Although obesity is an independent risk factor for the development of gastro-oesophageal reflux, the anatomical alterations of bariatric surgery may also be refluxogenic.1 Duodenal contents (bile, bicarbonate and pancreatic enzymes) may reflux into the stomach and oesophagus, which is called duodenogastro-oesophageal reflux (DGOR) or biliary reflux.

It is well documented that bile acids, together with gastric acid, contribute to reflux-type symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, etc.), erosive oesophagitis and Barrett's oesophagus.1

Validated investigations exist for the diagnosis of acid gastro-oesophageal reflux; however, detection of bile-containing reflux, with subsequent diagnosis of DGOR, is more difficult and there is no accepted gold standard.2

Bilitec ambulatory monitoring was developed specifically for the detection of bile reflux, but is prone to errors, especially false positive readings, while ambulatory pH monitoring and multichannel impedance-pH (MII-pH) take a measurement of total reflux rather than a specific measurement of DGOR.1 Unfortunately, none of the current ambulatory techniques are ideal.

Direct aspiration of gastric and oesophageal fluid allows chemical analysis of the concentration and composition of the fluid and determination of the presence of bile acids. Aspiration can be performed endoscopically during the test or through a nasogastric tube, and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry can provide quantitative analysis of bile acids.3 Fluid collection during endoscopy has the advantage of direct visualisation of the fluid and allows an assessment of the oesophageal and gastric mucosa, with the added advantage of tissue biopsy. Endoscopic features are as follows: presence of a gastric bile reservoir, acute gastritis with erythema, thickened gastric folds or mucosal erosions.4 Histological findings include foveolar hypertrophy, intestinal metaplasia and acute or chronic inflammation.4

Obviously, these findings are not specific for biliary reflux, thus limiting the diagnostic value of endoscopic visualisation and histological analysis when used in isolation.

The intermittent nature of bile reflux also limits the usefulness of isolated gastric and oesophageal fluid aspirates. In the case of endoscopy, sedation and hospital admission significantly increase cost, infrastructure requirements and patient acceptance.

Of the available techniques, HIDA scanning is the least invasive, but provides only a short window for capturing DGOR events. A more complete profile requires prolonged monitoring. Patient tolerability is also of key importance, with HIDA scanning having superior patient tolerability to catheter-based techniques. In available comparative studies, HIDA scintigraphy shows higher sensitivity and specificity than endoscopy and gastric and oesophageal fluid aspiration.1

It is not possible to distinguish between the available techniques on the basis of cost either, due to the small economic margin between them. Endoscopy and HIDA scanning have infrastructural requirements, as they need a staffed endoscopy room and a gamma camera with CT and SPECT, respectively. However, MII-pH and Bilitec monitoring also requires a highly skilled healthcare professional for catheter placement and interpretation of the acquired data.

The use of a bile acid-specific biosensor, using polymers capable of forming covalent bonds with bile acids, has been conceptualised; this technique remains an undeveloped concept, but illustrates a potential area of advancement. Other techniques, such as duodenal sodium counting with electrodes or intraluminal gamma-chamber measurement, are still experimental.1

Techniques that apply Doppler principles with a probe placed over the epigastrium and record the retrograde flow of enteric contents through the pylorus into the stomach are some of the advances that have been made. However, movement of the pylorus during respiration interrupts continuous visualisation and the extent and duration of exposure cannot be determined. It has therefore not been adopted in this field.

In the short-term wireless devices, such as those used for pH monitoring (Bravo™, Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA), will potentially improve the uptake of ambulatory recording techniques, with improved tolerability.1 There is scope for further progress in bile reflux detection techniques.

At present, although there is no gold standard, the HIDA scan is the least invasive scan, with good patient tolerability, sensitivity and reproducibility to be considered first-line for the diagnosis of bile reflux.

It should be added that there are currently no specific questionnaires separating bile reflux and gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms, which increases the difficulty of diagnosis.

Role of duodenogastro-oesophageal refluxIn the latest systematic review analysing the prevalence, symptoms, lesions and treatment of DGOR, several studies both in vitro and in vivo have implicated duodenal contents in the pathogenesis of oesophagogastric lesions.5

Patients with more advanced oesophageal lesions have a higher degree of duodenal reflux than those with simpler lesions. It has been demonstrated in animal models and in vitro that there is more Barrett's and dysplasia with duodenal reflux.6

Recent trials that have attempted to directly treat bile as a component of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) have demonstrated an improvement in symptoms and lesions in these patients. Forty percent of patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) have inadequate response to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and of these, 45 %–68 % have duodenal reflux, but the scientific evidence is so far insufficient to say that this is the cause of PPI non-responders. Furthermore, treating biliary reflux has not been shown to decrease or reverse Barrett's once established.5

Treatment used in vitro, such as alginates, have been shown to improve bile reflux. Famotidine/12 h in therapies of 5 days to 8 weeks decreases this reflux. Combined therapy of PPIs and baclofen at doses of 5–20 mg/8 h is effective and decreases this reflux from 13.8% to 6.1%.5

A new therapy, called IW-3718 (Colesevelam), binds and neutralises bile in the stomach, decreasing the volume of reflux and improving endoscopic imaging in 87% of cases, while also increasing muscle tissue relaxation.5

DGOR increases the prevalence of more advanced oesophageal lesions and we must continue to advance future therapies to address this reflux.

Scientific evidenceRenewed interest in biliary reflux has arisen especially after a particular bypass surgery used for obese patients such as the one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB), which is now the third most common bariatric and metabolic surgery procedure performed worldwide.1 By avoiding the second anastomosis associated with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), OAGB is said to be easier and avoids the potential complications associated with enteroenterostomy, but exposes the gastric reservoir to biliary reflux.

Some meta-analyses have shown equivalent metabolic outcomes when compared to RYGB and gastric sleeve (GS). Despite these results, OAGB has not been enthusiastically accepted due to the potential impact of postoperative biliary reflux.7,8

After OAGB surgery a small amount of bile may be transiently present in the stomach in about 50% of cases, leading to a mild chronic gastritis marked by the presence of foveolar hyperplasia, a specific marker of bile contact with the gastric mucosa. Highly intense and symptomatic biliary gastritis may occur, but is rarely observed.9

Bile reflux into the oesophagus is a complication that occurs in a variable percentage of cases in the various published series. The most frequent rates are 2%, with a range of 0-5.6%. A recent prospective study7 revealed that a low volume reflux of bile into the gastric pouch is common after OAGB and SG, in contrast to RYGB.

This is often referred to as DGOR, but strictly speaking it is not a correct term in relation to the anatomy of OAGB. The possibility of bile reflux is due to anatomical similarities with the Mason gastric bypass and the Billroth II procedure, both of which are associated with duodenogastric and oesophageal bile reflux and thus potential cancer risk.7

The relatively low frequency and low severity of biliary reflux can be explained by the presence of a wide anastomosis, greater than 3 cm in diameter, which allows easy and rapid gastric emptying, making it a low-pressure system in which intragastric pressure and the oesophagogastric pressure gradient are reduced, contrary to what happens in the GS. The fact that bile is poorly concentrated due to reabsorption in the biliopancreatic loop over its 2 metre length and dilution in the refluxed enteric contents decreases the noxious potential of bile.7,10

This mechanism contrasts with the Billroth II transit reconstruction technique, in which the gastroenteric anastomosis is placed closer to the angle of Treitz and at this level the enteric liquid enters with a higher concentration of bile salts, which is more aggressive. Due to the conformation of the more horizontal gastric pouch, a bile reservoir is formed that will reflux more towards the stomach and oesophagus.

This phenomenon occurs when a short reservoir is left in this OAGB surgery and allows this reflux. If an OAGB is correctly constructed with a long and narrow gastric pouch, no damage to the vagus nerves, with a well-constructed anastomosis, correct alignment between the reservoir and the common loop, it should have a low incidence of reflux of the enterobiliary contents into the stomach and oesophagus.11

The length of the reservoir should always be greater than 15 cm (12–19) and narrow, which is transformed by intra-abdominal pressure into an organ with a virtual lumen and rapid emptying in the absence of the pylorus.

Duodenogastric reflux can occur physiologically and is of minimal concern,7,12 while oesophageal bile has the potential to be associated with mucosal damage. Exposure of the oesophageal mucosa to bile acids increases epithelial permeability and promotes intracellular translocation of bile acids.12 Once intracellular, bile acids can incite an inflammatory response, causing oxidative DNA damage and cell death, thereby potentially initiating a Barrett's oesophagitis-adenocarcinoma sequence.7 De novo gastro-oesophagitis has been demonstrated in up to 58% of patients undergoing OAGB,7 compared to 39.5% reported by Saarinen et al. 11

Despite the known histopathological links between oesophageal mucosal exposure to bile and carcinogenesis, only two cases of gastric pouch/distal oesophageal malignancy have been described in 20 years since the advent of OAGB.13,14 Both were adenocarcinomas of the distal oesophageal junction, diagnosed 2 years postoperatively. One of the patients had known grade C oesophagitis preoperatively; in the other no preoperative endoscopy had been performed.

Similarly, based on long-term evidence from studies of patients undergoing a Billroth II procedure, concerns about bile-related carcinogenesis may be unfounded. In a population-based study of over 18,000 patients, the incidence of gastric stump cancer after Billroth II was not different from the expected incidence in the standard population (73/8,735 cases after Billroth II versus 83 expected).15 These studies show that the actual rate of malignancy is almost certainly incredibly low, with no demonstrable relationship to biliary reflux. This study has limitations because participants were not randomised to their procedure and participants with pre-existing reflux or Barrett's oesophagus on pre-operative endoscopy were positively selected for RYGB to minimise post-operative reflux.

However, with only two cases of post-OAGB malignancy reported in 20 years, both without correlation to a biliary aetiology, it is likely that the theoretical carcinogenic risk remains exactly that: theoretical.

A single prospective trial has shown that biliary reflux is a common finding by HIDA and endoscopy. Gastric bile reflux was present in one third of patients and oesophageal bile reflux in one case. Endoscopic findings were mainly in the gastric reservoir, and macroscopic lesions were rarely found.16

These results suggest that prospective trials of OAGB should include endoscopy preoperatively and at 5-year intervals to provide data on the true effects of bile exposure in the gastric reservoir and oesophagus.

High-level studies analysing this risk are currently lacking; the only prospective randomised study that has compared OAGB to RYGB with endoscopic evaluation is the YOMEGA.17,18 Robert et al.17 reported a higher rate of oesophagitis in the OAGB group (10%) compared to the RYGB group, with one case of oesophageal intestinal metaplasia observed after OAGB and no cases observed after RYGB 2 years after surgery.

In vivo, an experimental model of OAGB has been developed in rats, and after a 30 week follow-up, no incidences of dysplasia or cancer were observed in all three groups. In addition, oesophageal intestinal metaplasia and mucosal ulcerations were observed in 41.7% and 50% of oesophagojejunostomy (EY) rats, respectively, and no incidence of these conditions was observed in OAGB and sham rats. The incidence of oesophagitis was significantly higher and more severe in the EY group compared to the OAGB and sham groups.19

These observations in rats demonstrate that the OAGB model is not superimposable to the EY model with regard to oesophageal carcinogenesis and the longer gastric reservoir has a potential protective effect. Further long-term studies in rats and humans are needed to confirm these promising results.

Several experimental studies in general surgery have demonstrated different toxicities of bile acids depending on pH concentrations.20 In fact, higher pH values in gastric contents correspond to higher bile acid toxicity. This theory is probably one avenue to better understand the effects of these factors on the oesophageal mucosa. Importantly, this pathway is especially important because most operated patients (even after omega bypass surgeries) receive proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) that cause an increase in the pH of gastric contents, leading to a potential increase in bile acid toxicity in humans.19

In a meta-analysis by Portela et al.21 performed on the SADIS technique, biliary reflux has not been shown to be a problem and gives a figure of 7.6% compared to 26.7% in OAGB.

A particularly difficult entity to diagnose and treat is gastritis of the gastric remnant due to biliary reflux, a cause of chronic pain that occurs months or years after RYGB.22

In a meta-analysis by Portela et al.21 performed on the SADIS technique, biliary reflux has not been shown to be a problem and gives a figure of 7.6% compared to 26.7% in OAGB.

The HIDA scan is a sensitive measure of remnant pathology and is a readily available non-invasive test. HIDA and endoscopic biopsies are highly suggestive of biliary reflux remnant gastritis.

A number of symptomatic patients, months to years after RYGB, with chronic abdominal pain in the setting of bile reflux gastritis of the remnant were effectively treated with gastric remnant resection. This could therefore be a safe and effective treatment for bile reflux gastritis of the remnant, with long-term improvement and resolution of symptoms in most patients.22

HIDA scan and endoscopy are recommended in all patients with chronic abdominal pain after RYGB, once other common causes have been excluded, with an increasing level of treatment, from non-invasive, such as a trial of prokinetic drugs or Ursodiol 500 mg/12 h and increasing even up to 1,000 mg, to surgical treatment of gastric remnant resection or gastric bypass reversal.22

Biliary reflux treatment possibilitiesAs with all other bariatric procedures, revision surgery is inevitable after OAGB. But before surgery in patients with this DGOR, medical treatment is started first, and combinations of prokinetics, probiotics, ursodeoxycholic acid, proton pump inhibitors, baclofen and cholestyramine23 are recommended.

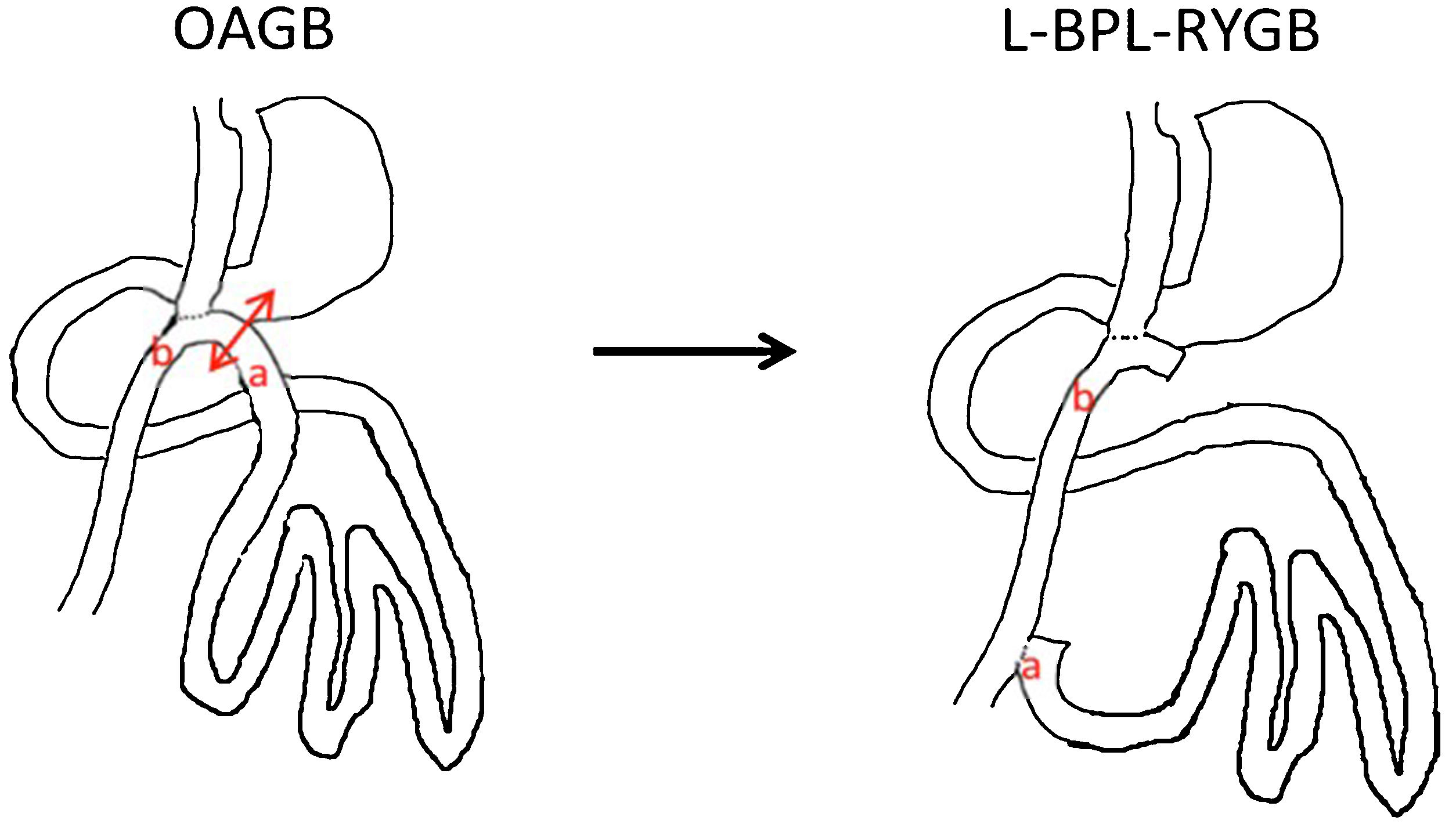

When medical therapy fails to produce results for up to 6 months, the indication for surgical revision should be established. In the surgical approach, Roux-en-Y bile diversion results in what is called long pouch gastric bypass (LPGB).24 Technically, disconnection of the biliopancreatic loop is performed immediately prior to gastroenterostomy and reanastomosis to the common loop 70 cm from the gastroenterostomy, followed by closure of the mesenteric gaps. The result is a RYGB with a 70 cm feeding loop, a 200 cm biliopancreatic loop and a common loop of at least 300 cm (Fig. 1).

In the case of Barrett's or oesophagitis grade C or D, it is advisable to disassemble the gastrojejunal anastomosis and convert it into a classic RYGB with a short pouch to avoid damage from residual acid secretion.

Some authors prefer to control biliary reflux using a Braun type enteroanastomosis, but this intervention is less effective and fails, requiring conversion to RYGB. Simple repair of a hiatus hernia, or even construction of a Toupet or Nissen valve, are possible alternatives, but with inconsistent outcomes.25

Reversal of surgery has been described in cases of severe reflux associated with malnutrition, always in consensus with the patient, based on the evident risk of weight regain. However, the final result of reversal of the stomach that is still bipartite, such as Magenstrasse and Mill, means that weight regain does not always occur.24

Khrucharoen et al.,26 reviewing the current literature, stated that the most commonly employed surgical technique for revision OAGB is RYGB, followed by reversion to GS, restoration of the original anatomy and gastrogastrostomy alone.

They also found that the most common indications for revision surgery were intractable malnutrition and biliary reflux, and concluded that the choice of approach appeared to depend on both indication and institutional preference: revision to RYGB, which is technically simpler compared to reversion to normal anatomy, may be necessary in patients with severe biliary reflux, but should be avoided in those with severe malnutrition.

Similarly, Hussain et al.27 analysed data from a large series of 925 OAGB, and in 22 cases (2.3%) secondary surgery was necessary: five patients (.5%) developed severe diarrhoea which was treated by shortening the biliopancreatic branch and three patients (.3%) developed intractable biliary reflux and were treated by conversion to RYGB.

The YOMEGA trial shows serious adverse effects after OAGB, especially malnutrition, as well as intractable biliary reflux (1.6%), which required conversion to RYGB.17

A recent Italian multi-institutional study28 evaluated revision surgery in a total of 8,676 patients with OAGB, showing intractable DGOR in .94%, with RYGB being the most commonly performed revision procedure, followed by biliopancreatic branch elongation and restoration of normal anatomy. Studies such as this one demonstrates that there is an acceptable revision rate after OAGB and that conversion to RYGB represents the most frequent option.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Frutos Bernal MD, Reflujo biliar tras cirugía bariátrica. Cir Esp. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2023.02.002