This letter is in regard to the article published in your journal in September 2015 by Abad Calvo et al., “Abdominal Cocoon Syndrome: A Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenge.”1

We would like to present a recent case at our hospital of a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis (Child–Pugh B) who underwent orthotopic liver transplantation. During the surgical procedure, signs compatible with Cocoon syndrome were observed that had not been detected by preoperative imaging tests (a series of abdominal ultrasounds over previous months), which was later confirmed by the pathology study. We would like to comment on this case with the medical community because of the liver involvement, which, according to the reviewed literature, is particularly uncommon and has not been documented with images. Likewise, we also report our experience in terms of technical difficulties that could be posed by the presence of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) during a surgical procedure of this nature.

Secondary EPS is a rare complication, whose pathogenesis, although still uncertain, is explained in most cases by recurrent inflammatory peritoneal reactions.2,3 This would be the case of our patient, who presented ascites on several occasions. Within the semiological scenario of EPS, most publications report that the most commonly affected organ is the intestine,1,4,5 and few articles mention the rare involvement of the supramesocolic organs.6–9 Even an extensive review of 193 patients by Akbulut9 describes the clinical symptoms derived from intestinal involvement, but not of hepatic and/or gastric involvement. However, our patient had involvement mainly of the liver and stomach, and the small intestine to a lesser degree.

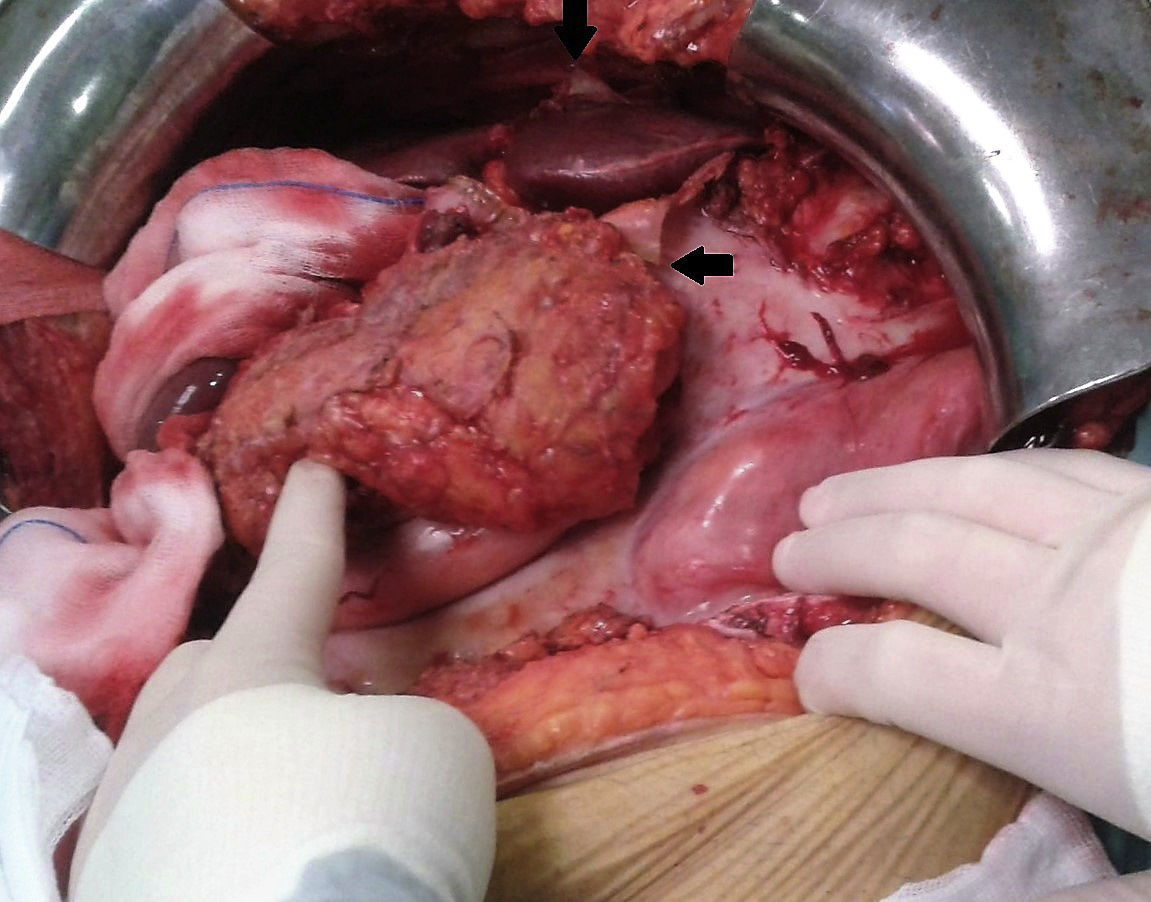

During surgery, we detected the presence of a pearly-white membrane encapsulating most of the organs of the supramesocolic compartment, which made it difficult to open the abdominal cavity and observe the liver and its vascular pedicle. The dissection of the elements of the hepatic hilum was especially painstaking. Therefore, in the operating room, we decided to initially release the prehepatic fibrotic capsule (Fig. 1). Afterwards, we opted to perform en bloc resection of the hepatic hilum, with prior clamping (Pringle), and then dissected its elements once the hepatectomy was completed and enough space had been created to provide for its correct identification.

Thus, we conclude that EPS could affect, albeit uncommonly, the organs of the supramesocolic compartment, representing a challenge during the vascular-biliary surgical management of liver transplantation, although it is not a contraindication.

FundingNo funding was received for the completion of this manuscript.

AuthorshipIsabel Casal Beloy, María Alejandra García Novoa: composition of the manuscript, data collection.

Jose Ignacio Rivas Polo: critical review of the manuscript, data collection.

Manuel Gómez Gutiérrez: critical review of the manuscript, approval of the final version of the manuscript, data collection.

Please cite this article as: Casal Beloy I, García Novoa MA, Rivas Polo JI, Gómez Gutiérrez M. Síndrome de Cocoon con afectación hepática. Hallazgo casual durante un trasplante hepático ortotópico. Cir Esp. 2017;95:485–486.