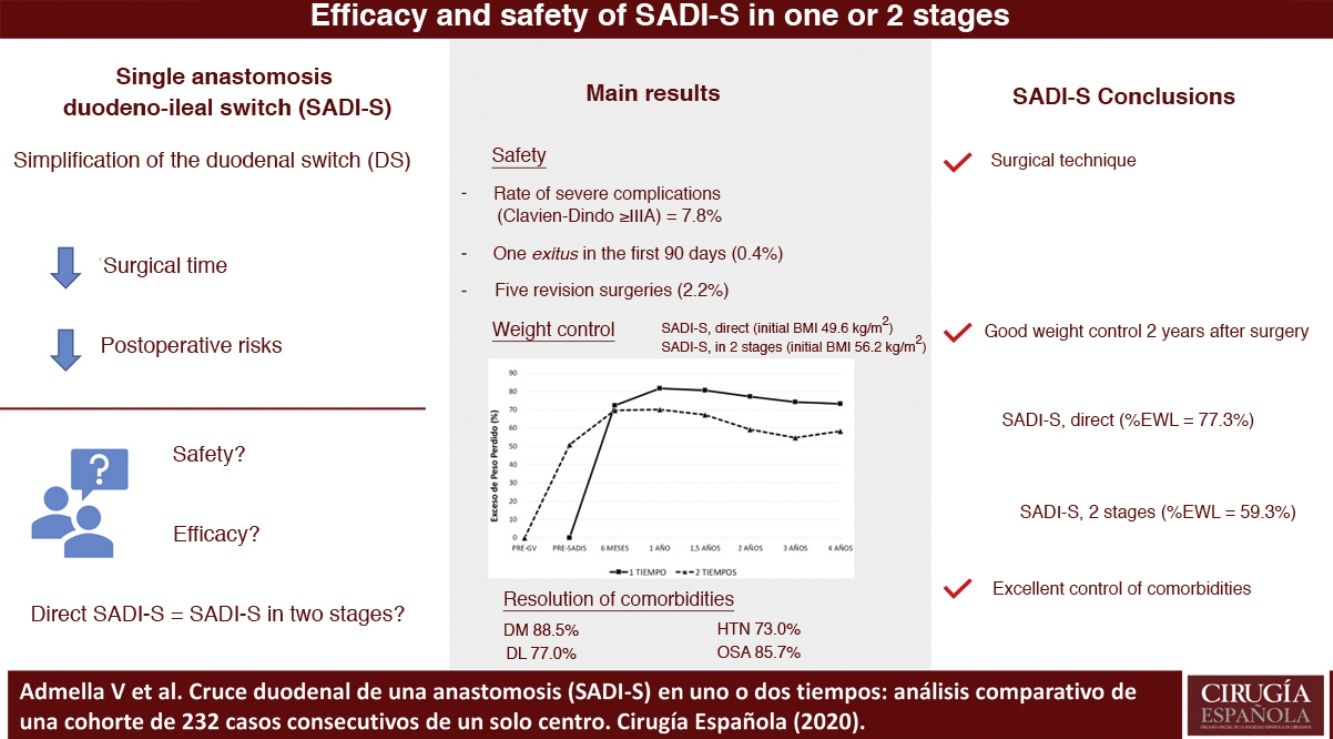

The “Single Anastomosis Duodeno-Ileal bypass with Sleeve gastrectomy” (SADI-S) is a bariatric surgery conceived to simplify the duodenal switch in order to reduce its postoperative complications. The objective of this study is to assess the safety and efficacy of SADI-S, comparing its results in both direct and two-step procedure.

MethodsUnicentric cohort study that includes patients submitted to SADI-S, both direct or in two-step, between 2014 and 2019.

ResultsTwo hundred thirty-two patients were included, 192 were submitted to direct SADI-S and 40 had previously undergone a sleeve gastrectomy. The severe complications rate (Clavien-Dindo ≥ IIIA) was 7.8%, being hemoperitoneum and duodenal stump leak the most frequent ones. One patient was exitus between the first 90 days after surgery (0.4%). Patients submitted to direct SADI-S had an initial body mass index (BMI) of 49.6 kg/m2 in comparison of 56.2 kg/m2 in the two-step SADI-S (P < .001). The mean excess weight loss (EWL) at two years was higher in direct SADI-S (77.3 vs. 59.3%, P < .05). Rate of comorbidities resolution was 88.5% for diabetes, 73.0% for hypertension, 77.0% for dyslipidemia and 85.7% for sleep apnea, with no differences between both techniques.

ConclusionIn medium term, SADI-S is a safe and effective technique that offers a satisfactory weight loss and remission of comorbidities. Patients submitted to two-step SADI-S had a higher initial BMI and presented a lower EWL than direct SADI-S.

El cruce duodenal de una anastomosis (SADI-S) es una cirugía bariátrica concebida como una simplificación del cruce duodenal. El objetivo de este estudio es valorar su seguridad y eficacia, comparando los casos operados en uno o dos tiempos.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo unicéntrico que compara los resultados de pacientes intervenidos de SADI-S en uno o dos tiempos entre 2014 y 2019.

ResultadosSe incluyeron a 232 pacientes, 192 operados directamente y 40 sometidos previamente a una gastrectomía vertical. La tasa de complicaciones Clavien-Dindo ≥ IIIA fue 7,8%, siendo las más frecuentes el hemoperitoneo y la fístula de muñón duodenal. Hubo un éxitus en los primeros 90 días del 0,4%. Los pacientes sometidos a SADI-S directo partieron de un índice de masa corporal (IMC) de 49,6 kg/m2 y los operados en dos tiempos de 56,2 kg/m2 (P < ,001), siendo el exceso de peso perdido a los dos años de ambos grupos de 77,3% y 59,3% respectivamente (P < ,05). La tasa de resolución de la diabetes, hipertensión arterial, dislipemia y síndrome de apnea obstructiva del sueño fue de 88,5, 73,0, 77,0 y 85,7% respectivamente, sin diferencias entre el SADI-S en uno o dos tiempos.

ConclusiónEl SADI-S es una técnica segura y eficaz a medio plazo para la pérdida de peso y control de comorbilidades. Los pacientes intervenidos en dos tiempos partieron de un IMC mayor y presentaron menor porcentaje de exceso de peso perdido que los operados directamente.

The duodenal switch (DS) has proven to be the most effective surgical procedure for the treatment of morbid obesity and its comorbidities.1–5 However, it currently represents a small percentage of bariatric surgeries performed around the world, probably due to its technical complexity and the risk of long-term complications.6,7 With the intention of simplifying the DS technique, in 2007 Drs Sánchez-Pernaute and Torres introduced the DS with one anastomosis (Single Anastomosis Duodeno-Ileal bypass with Sleeve gastrectomy, or SADI-S).8 The omega reconstruction, avoiding the distal ileo-ileal anastomosis, aims to reduce surgical time and postoperative risks.9 The SADI-S consists of a sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and a duodenal-ileal anastomosis with preservation of the pylorus, jejunal exclusion and a total common-alimentary limb, originally measuring 200 cm and later standardized to 300 cm to reduce the risk of nutritional deficiencies. SADI-S can be performed as direct primary surgery, planned in two stages, or as revision surgery in case of failed weight loss after SG.

Despite the potential advantages of SADI-S, there are few reports in the literature describing its results in large, homogeneous series. The objective of this study is to assess postoperative complications, weight loss, remission of comorbidities, and nutritional deficiencies in a cohort of patients treated with SADI-S at a single tertiary hospital. We will also compare the safety and efficacy of performing this technique in one or two stages.

MethodsStudy design and populationWe conducted a descriptive study of patients who underwent SADI-S in one or two stages between May 2014 and September 2019. Bariatric surgery was indicated following the criteria of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).10 The therapeutic algorithm of our unit indicates hypoabsorption techniques in patients with a body mass index (BMI) ± 45 kg/m2 with associated comorbidities and no symptoms suggestive of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), defined as the existence of retrosternal pyrosis, regurgitation and/or regular taking of proton pump inhibitors.

Preoperative circuitThe patients were evaluated by the multidisciplinary team composed of specialists in endocrinology, nutrition, psychiatry, pulmonology, anesthesia and surgery, receiving education on eating habits, type of surgery, and managing emotions. Afterwards, and before signing the informed consent, the risks and potential benefits of the surgery were discussed. Patients who had gained more than 10% of their total weight while awaiting surgery were excluded. One month before the operation, a 1500 kcal hypocaloric diet was indicated and, two weeks earlier, a liquid diet was started with 1500 kcal high-protein preparations to promote weight loss.

Surgical techniqueThe patients were operated on under general anesthesia in an anti-Trendelenburg position with legs apart, with the main surgeon standing between the patient’s legs. When measuring the small intestine, the lead surgeon positioned himself on the left side of the patient. Five trocars were placed in the supraumbilical area of the abdomen, and another in the left iliac fossa. The first step consisted of dissecting the duodenal bulb up to the gastroduodenal artery, systematically ligating the right gastroepiploic and right gastric arteries at their origins. The SG was started 6 cm from the pylorus, using a 36–40 Fr catheter. Subsequently, the duodenum was divided using an EndoGIA white-load stapler. The small intestine limb was measured from the ileo-cecal valve to a length of 300 cm, and a manual duodeno-ileal anastomosis was created with resorbable monofilament suture in two planes. Petersen’s space was closed using a running nonabsorbable suture. The suture was checked for leaks with methylene blue or endoscopy. Lastly, an intra-abdominal drain was placed close to the anastomosis and the angle of His.11

Postoperative follow-upDuring hospitalization, nutritional education was reinforced. At discharge, the patients were prescribed multivitamin supplements (group B, C and E vitamins, zinc, selenium and coenzyme Q10), vitamin D and calcium tablets (1000 mg calcium carbonate + 800 IU cholecalciferol), ursodeoxycholic acid (300 mg/8 h), bismuth subgallate (200 mg/8 h) and a protein module (20 g/day). The patients had follow-up office visits with a surgeon, endocrinologist and nutritionist after 1, 3, 6, 12 and 18 months, then annually up to six years, including lab work at 3, 6, 12, 18 months and annually thereafter.

Data collection and definitionsData were obtained from a prospective database, including demographic variables, weight, diabetes mellitus (DM), arterial hypertension (HTN), dyslipidemia (DL), obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), type of surgery, complications in the first 30 days (type and severity according to the Clavien-Dindo score), mortality at 30 and 90 days, postoperative evolution of weight at six months, one year and then annually, resolution of comorbidities, long-term complications, need for extraordinary supplementation due to nutritional deficiencies and revisional surgeries. The percentage of excess weight lost (%EWL) was calculated by taking as reference an ideal BMI of 25 kg/m2. The resolution of comorbidities was defined as the complete withdrawal of the specific treatment.

Statistical analysisAs it was a cohort study, a previous hypothesis was not made, nor was a sample size calculated.12 The evolution of body weight was expressed by %EWL and BMI. The differences between the SADI-S in one or two stages were studied using a chi-squared analysis for the discrete variables and Student’s t test for the continuous variables; a difference was considered significant if P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed with the IBM-SPSS Statistics 20® program.

ResultsBaseline demographic and surgical dataThe study included 232 patients who underwent SADI-S, 192 (82.8%) directly and 40 (17.2%) after SG, with a mean interval between both surgeries of 34.3 months (range 6.2–107.1 months).

Table 1 describes the main characteristics of the patients who underwent SADI-S in one or two stages. The patients operated on directly were older (51.7 vs 44.6 years; P < .001) and had lower initial BMI than those operated on in two stages (49.6 vs 56.2; P < .001). In the prevalence of comorbidities, both groups were homogeneous except for hypertension (P < .05). All procedures were performed laparoscopically, except for four cases that were operated on by open surgery: one patient with a history of several previous surgeries, and three conversions due to technical difficulties.

Baseline and postoperative demographic characteristics of patients who underwent SADI-S in one and 2 stages.

| SADI-S, direct n = 192 | SADI-S, 2-stages n = 40 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Post SADI-S | Initial | Post SG | Post SADI-S | |

| Age, mean (SD) yrs | 51.7 (8.6)** | 44.6 (10.6)** | |||

| Female sex, n (%) | 144 (75) | 28 (70) | |||

| Max. BMI, mean (SD) kg/m2 | 49.6 (5.1)** | 30.7 (4.1)/2 yrs* | 56.2 (7.8)** | 40.1 (6.1) | 36.8 (4.7)/2 yrs* |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| DM | 68 (35.4) | 10 (25) | |||

| Resolution of DM | 61 (89.7) | 6 (60) | 8 (80) | ||

| HTN | 113 (58.9)* | 13 (32.5)* | |||

| Resolution of HTN | 83 (73.4) | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | ||

| DL | 51 (26.6) | 10 (25) | |||

| Resolution of DL | 40 (78.4) | 5 (50) | 7 (70) | ||

| OSA | 80 (41.7) | 18 (45) | |||

| Resolution of OSA | 69 (86.2) | 8 (44.4) | 15 (83.3) | ||

| Laparoscopy, n (%) | 189 (98.4) | 39 (97.5) | |||

| Associated cruroplasty, n (%) | 60 (31.2)* | 5 (12.5)* | |||

DL: dyslipidemia; DM: diabetes mellitus; HTN: arterial hypertension; BMI: body mass index; SADI-S: single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

The mean patient follow-up was 22.3 ± 12 months (3.3–63.9 months), with no differences between the patients treated in one or two stages (22.5 ± 12 vs 21.4 ± 14 months). The numbers of patients with follow-up after 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were 175, 68, 27, and 11, respectively.

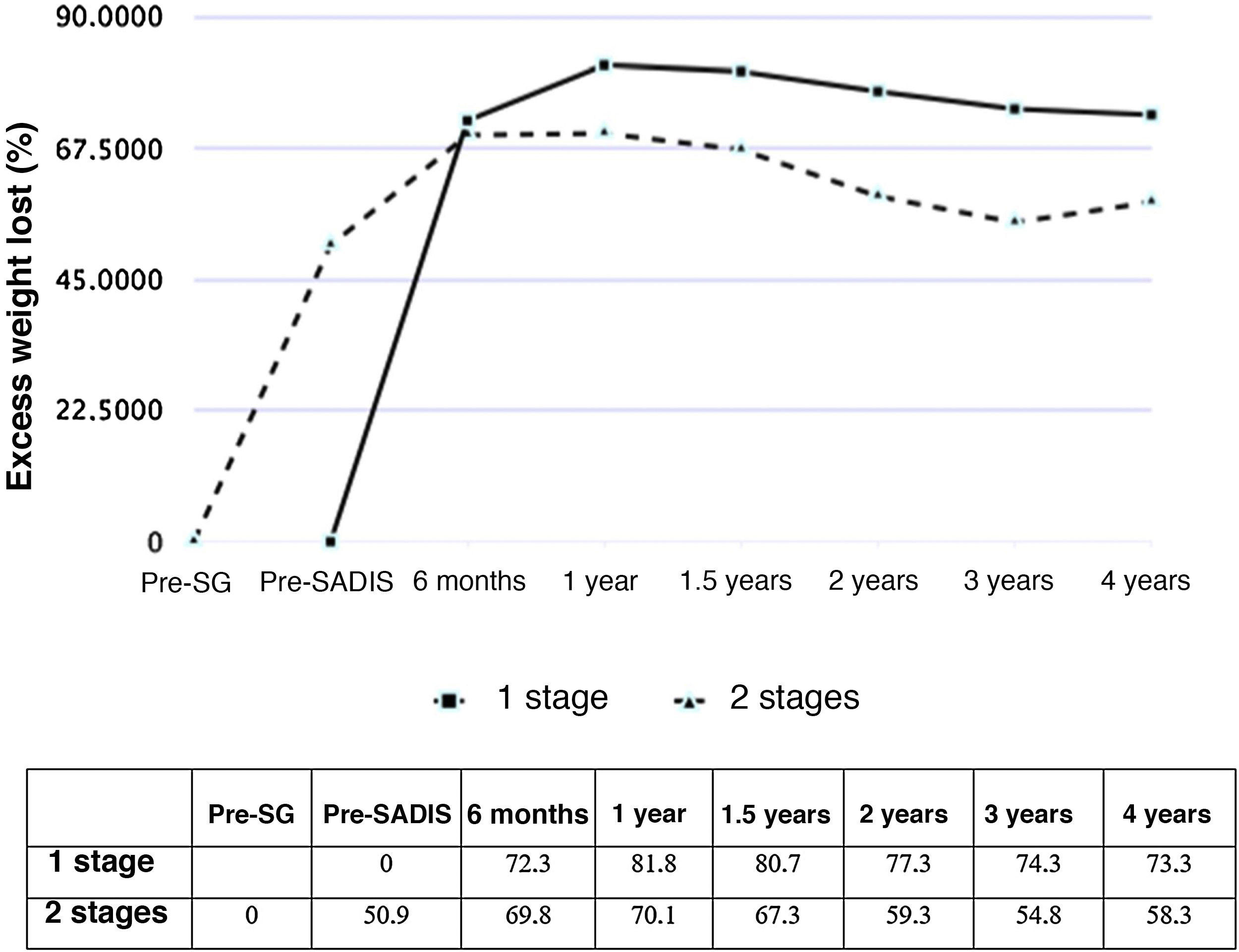

Figs. 1 and 2 show the evolution of BMI and %EWL in both groups. In patients treated directly, the %EWL was 81.8% after one year and 73.3% after 4 years. In those operated on in 2 stages, considering the maximum weight before the SG, the %EWL after SG was 50.9%, reaching a maximum of 70.1% 6 months after the SADI-S and decreasing to 58.3% after 4 years. The percentage of total weight lost was 40.3% one year after surgery and 38.5% 2 years afterwards, with no significant differences between the SADI-S in one or 2 stages.

The overall resolution rates of DM, HTN, DL and OSA were 88.5%, 73.0%, 77.0% and 85.7%, respectively, with no differences observed between the SADI-S in one or two stages (Table 1).

Postoperative complications and revision surgeriesTable 2 summarizes short-term (<30 days) and long-term (>30 days) complications. The overall rate of short-term complications was 13.4% and that of severe complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ IIIA) was 7.8% with no differences between the two groups. The most frequent complications were hemoperitoneum (3.0%) and duodenal stump fistula (1.3%), both only in patients who underwent direct SADI-S. There were no complications secondary to previous SG in patients treated in 2 stages. The mean post-SADI-S hospital stay was 2.9 ± 2 days, with no differences between the 2 groups. There was one case of mortality in the first 30 days (0.4%) due to infarction after reoperation for hemoperitoneum. There were no deaths between postoperative days 30 and 90.

Short-term (<30 days) and long-term (>30 days) complications after SADI-S in one or 2 stages.

| SADI-S, direct n = 192 | SADI-S, 2 stages n = 40 | |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term complications, n (%) | 26 (13.5) | 5 (12.5) |

| Fistula of the duodeno-ileal anastomosis | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Fistula of the duodenal stump | 3 (1.6) | 0 |

| Gastric fistula | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Hemoperitoneum | 7 (3.6) | 0 |

| Intraabdominal collection | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Internal hernia | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Incarcerated incisional hernia | – | 1 (2.5) |

| Surgical wound bleeding | 2 (1) | 1 (2.5) |

| Clavien-Dindo score, n (%) | ||

| I–IIB | 11 (5.7) | 2 (5) |

| ≥IIIA | 15 (7.8) | 3 (7.5) |

| Hospital stay post-SADI-S, mean (SD) days | 2.7 (1.8) | 2.2 (0.7) |

| Global hospital stay, mean (SD), days | 2.7 (1.8)* | 4.4 (0.9)* |

| 90-day post-op mortality, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Long-term complications, n (%) | 15 (7.8) | 4 (10) |

| Internal hernia | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Incarcerated incisional hernia | 1 (0.5) | 1 (2.5) |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| GERD | 12 (6.3) | 3 (7.5) |

| Intestinal obstruction due to bands | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Constipation | 5 (2.6) | 0 |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 16 (8.3) | 3 (7.5) |

GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; SADI-S: single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy.

The overall complication rate >30 days was 8.2%. The most frequent was symptomatic GERD, which was present in 15 patients (6.5%) and showed biliary etiology in three. Two patients (0.9%) had an internal hernia due to a Petersen space defect 12 days and four months after SADI-S. A total of 19 patients (8.2%) required urgent reoperation due to short- or long-term complications. The main reasons for reoperation included hemoperitoneum, and the entire set of patients who presented this complication were treated surgically during hospitalization; other reasons included the presence of a duodenal stump fistula, incarcerated incisional hernia and internal hernia. There were 5 revision surgeries (2.2%): 2 for weight regain, 2 for persistent bile reflux, and one for anastomotic stenosis, converting to DS in all cases.

Need for nutritional supplementsTable 3 describes the nutritional supplementation needs. No differences were observed between the direct or 2-step SADI-S. There were no cases of hypoalbuminemia or protein malnutrition that required supplementation or revisional surgery.

Global percentage of patients with additional nutritional supplements after SADI-S.

| Additional nutritional supplements n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Vitamin A | 25 (10.9) |

| Vitamin B | 4 (1.7) |

| Vitamin D | 65 (28.4) |

| Vitamin E | 0 |

| Vitamin K | 0 |

| Calcium | 22 (9.6) |

| Iron | 36 (15.7) |

| Copper | 3 (1.3) |

| Zinc | 2 (0.9) |

| Albumin | 0 |

| Folic acid | 36 (15.7) |

Our cohort study confirms that the SADI-S technique, in either one or 2 stages, is a safe and effective technique in patients with a BMI > 45 kg/m2 for controlling both weight and comorbidities. Currently, this is one of the largest international reference cohorts in terms of number of patients and follow-up.

Safety7.8% of the patients had early severe complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ IIIA), with an overall reoperation rate of 8.2% and a mortality of 0.4%, values similar to those described in the literature.13,14 No differences were observed in the proportion of complications or in the post-SADI-S hospital stay between the direct or two-step SADI-S, which also concurs with previous studies.15,16 However, the complications in direct SADI-S were more relevant: cases of hemoperitoneum and duodenal stump fistula only occurred in this group. Biertho et al. reported that the risk of duodeno-ileal anastomosis fistula decreased from 2.6% to 0.4% when they switched from circular mechanical suture to manual suture.17 Manual anastomosis was performed in all the patients in our cohort, presenting an overall risk of duodenal-ileal anastomosis fistula of 0.4%. Our group began the practice of this anastomosis in 2008 with DS, so by introducing the SADI-S in 2016, the learning curve was avoided.

As in other bariatric surgeries, closure of the Petersen space is controversial. At our hospital, we close it systematically in the SADI-S, DS and gastric bypass. Currently, there is only one published case of internal hernia after SADI-S18; the two cases reported in the present study represent 0.9% of our cohort. DS, in which the mesentery is divided, presents internal hernia rates of up to 8%.19

One of the arguments of the opponents of SADI-S is the possibility of bile reflux. In our series, there were three symptomatic cases. It would be reasonable to expect a greater incidence in techniques with Billroth II reconstruction that do not preserve the pyloric barrier, such as the mini-gastric bypass. Although the published incidences of symptomatic bile reflux after a mini-gastric bypass range from 0.5% to 1.5%,20,21 comparable to those in our study, it should be remembered that not all bile reflux is symptomatic and that biliary gastritis is a premalignant condition.22

Our patients presented a need for supplementation greater than what is typical of DS,23–25 although there were no cases of malnutrition. It is known that the absorption of nutrients, especially fat-soluble vitamins, is directly related to the length of the common limb.26 The SADI-S originally described, whose efferent limb was 200 cm, presented hypoalbuminemia rates of 12% and revisional surgery for diarrhea of up to 5%.9 The patients in this cohort had a 300 cm efferent loop, a technical variant that some authors have called ‘SIPS’ (Stomach Intestinal Pylorus-Sparing surgery).27,28

EffectivenessThe patients who underwent direct SADI-S presented optimal weight control in the medium term. After three years, a BMI of 30.7 kg/m2 was reached, similar to the 28.1 kg/m2 reported by Torres et al.29 The %EWL of our study (77.3% after 2 years) is comparable with the range of 72%–100% described in the systematic review by Shoar et al,30 despite the fact that the initial BMI of our patients was 50 kg/m2, which is higher than the BMI of several of these studies. These global results are similar to those obtained by DS23 and superior to those of SG and gastric bypass, especially for the treatment of super obesity (BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2).1,4–6

The efficacy of the SADI-S in two stages was less satisfactory, presenting a %EWL 2 years after surgery of 59.3%, which is lower than in other similar series, like the Sánchez-Pernaute et al. (72%)15 and Balibrea et al. (78.9%)16 studies. One reason for the relative failure in this group of patients in our study could be their high initial BMI: 56.2 kg/m2 (vs 49.6 kg/m2 in direct SADI-S, P < .001). In a previous study, we found evidence that DS obtained better weight control than SADI-S in patients with initial maximum BMI ≥55 kg/m2 (BMI/2 years < 35 kg/m2 = 82.6% vs 65.7%; P < .05), as well as higher resolution of DM (100% vs 75%; P < .05).23 When deciding which technique to use in a patient with poor weight control after SG, it is important to assess the maximum pre-SG BMI; DS is preferable for ≥55 kg/m2. The initial failure of bariatric surgery selects patients with the lowest adherence to dietary recommendations, so it is especially necessary to assess the most effective technique for them. Another argument that could justify the difference in results between the 2 groups is the long time elapsed between SG and the SADI-S (mean 34.3 months); this may have caused the patients to adapt to the first surgical procedure, negatively influencing the 2-stage SADI-S weight loss results.

The overall resolution rate of comorbidities in this study was remarkable, with rates for DM, HTN, DL and OSA of 88.5%, 73.0%, 77.0% and 85.7%, respectively. These results are similar to those obtained by other hypoabsorption surgery studies and higher than those achieved after restrictive surgery.1,13,29,30

The limitations of the present study include its retrospective nature, which means it is possible that not all minor complications have been registered. Furthermore, only 4.7% of patients had a follow-up >4 years, which is why we still do not know the long-term behavior of SADI-S.

In conclusion, the SADI-S is a safe and effective technique in the medium term for weight loss and control of comorbidities, in both one and 2 stages, although the patients who underwent direct surgery presented complications of special relevance. The direct SADI-S group achieved better weight control than in 2 stages, but the starting BMI was also lower. Studies with long-term results are necessary to define the appropriate indication for SADI-S.

FundingNo funding was received of any kind regarding this article.

Conflict of interestsVíctor Admella, Javier Osorio, Maria Sorribas, Lucía Sobrino, Anna Casajoana, and Jordi Pujol-Gebellí have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Admella V, Osorio J, Sorribas M, Sobrino L, Casajoana A, Pujol-Gebellí J. Cruce duodenal de una anastomosis (SADI-S) en uno o dos tiempos: análisis comparativo de 232 casos de un solo centro. Cir Esp. 2021;99:514–520.