The objective was to explore, discuss and synthesize the emotional experiences of health professionals during the process of organ procurement and transplantation.

MethodsA systematic review was made in Medline, Science Direct and the Virtual Library of the Andalusian Public Health System, selecting 16 original articles for inclusion in the review, with qualitative evaluation and narrative synthesis.

ResultsThe results revealed the main use of qualitative methodology, and 4 emergent themes were identified: working in organ procurement and transplantation; the transition of professional roles; emotional experiences; and, coping strategies and emotional management. This systematic review revealed the complex and diverse character of professionals’ emotional experiences as well as the importance of the interpersonal relationship.

ConclusionsIntense emotional experiences related to the sense of responsibility, the work challenge and coping strategies based on reward searching explained important contradictions and tensions about professional roles and functions, especially during the donation interview.

El objetivo de este artículo fue explorar, analizar y sintetizar las experiencias emocionales de profesionales sanitarios de donación y trasplantes.

MétodoSe realizó una revisión sistemática cualitativa en Medline, Science Direct y la Biblioteca Virtual del Sistema Sanitario Público de Andalucía. Se seleccionaron 16 artículos originales, realizando una evaluación cualitativa y síntesis narrativa.

ResultadosSe identificó el uso mayoritario de métodos cualitativos y 4 temáticas emergentes: trabajar en donaciones y trasplantes; la transición de roles profesionales; vivencias emocionales, y afrontamiento y mejora de la gestión emocional. Se reflejaron la complejidad y la pluralidad de las vivencias emocionales y la centralidad del enfoque relacional.

ConclusionesLas intensas experiencias emocionales en torno a la responsabilidad vivida, la asunción del trabajo como un gran reto y la búsqueda de recompensas como principal estrategia de afrontamiento aparecieron como factores explicativos de importantes contradicciones y tensiones de roles y funciones, con especial relevancia durante la entrevista de donación.

In the current medical–surgical panorama of the Western world, organ transplantation is a therapy that is in constant development1 thanks to technological advances and new organ procurement alternatives.

Recent sources document the multifactorial causality of organ shortages3 despite the persistent increase in organ donation (with the highest rates in European countries, USA, Australia, Canada and Brazil).2 On one hand, the adoption of the presumed consent model4 or the organization of specific organ transplant coordinate teams (initially implanted in Spain, the US or Canada, but exported to many current systems5) have been effective to increase donation rates.6 However, there is also evidence of the importance of knowledge and attitudes, as well as the experience and preparation of health professionals in the process of requesting organ donations.3,7

According to current sources, the general attitude of medical personnel toward organ donation is positive (80%),8 although the psychological and social impact of requesting organ donation can generate significant professional dilemmas.8,9 These, together with the physical, mental and emotional demands of medical care,10,11 are important sources of stress, professional burnout, deteriorating health and professional satisfaction.12–14 Likewise, they could have a negative effect on the results of the donation interview.15,16

Following cognitive and phenomenological theoretical perspectives, in the 1990s several studies analyzed the stress factors associated with the phases of anticipation, confrontation and post-exposure confrontation experienced by medical personnel during patient management and in dealing with relatives during the donation/transplantation process.12,17 Among the coping strategies (efforts made to overcome, change or tolerate the demands of a difficult situation), the most common were to seek support, rely on previous experiences, maintain emotional distance, divert responsibilities and use positive reassessment.17,18

Studies focused on the needs and expectations of patients and their families highlighted the positive impact of observation, listening, empathy, understanding and professional companionship for the acceptance of donation.13,19–21

Until now, measures aimed at reducing stress and adapting healthcare were based on specific education and training programs for medical professionals.22 The most important training programs (European Donor Hospital Education Programme,23 the COPe Program24 [replicated in several countries], the Italian training model related with families ICU INTENSIVA.it,24 or continuous training in Turkey25) were aimed at improving donation rates, but they were not specifically designed to identify emotions or prepare professionals for emotional management.26

To provide a synthesized understanding that would facilitate the adaptation of support measures for better emotional management of medical personnel, the objective of this study was to explore, analyze and synthesize the experiences and emotional experiences of healthcare professionals specialized in the donation and transplantation process.

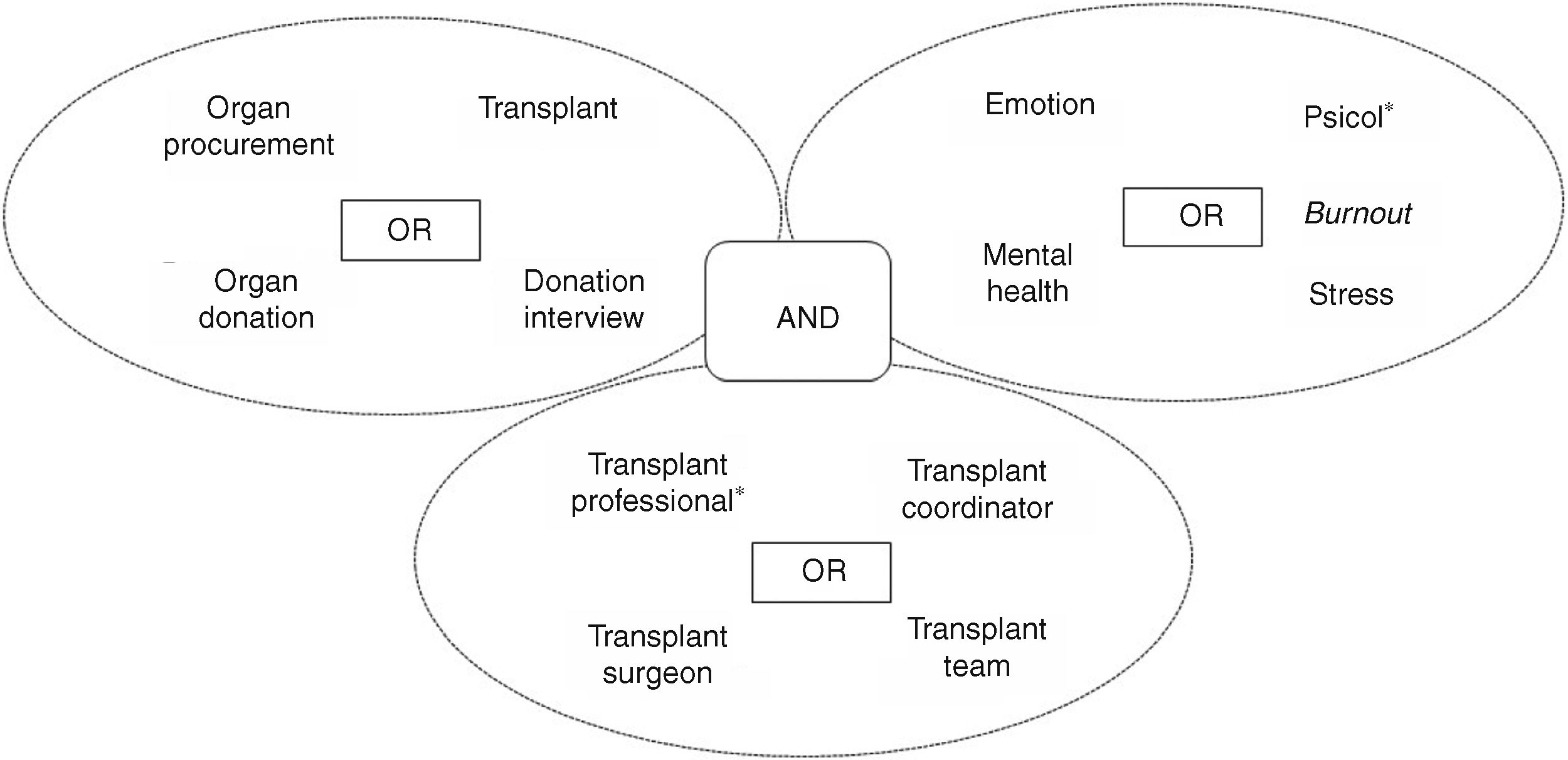

MethodsA qualitative systematic review was conducted of the literature published between 2000 and 2018 in: (1) Medline (PubMed); (2) Science Direct; and (3) database of the Virtual Library of the Public Health System of Andalusia through the Gerión search engine. The search strategy, Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms and Descriptors in Health Sciences (DECS) used to truncate the terms are presented in Fig. 1.

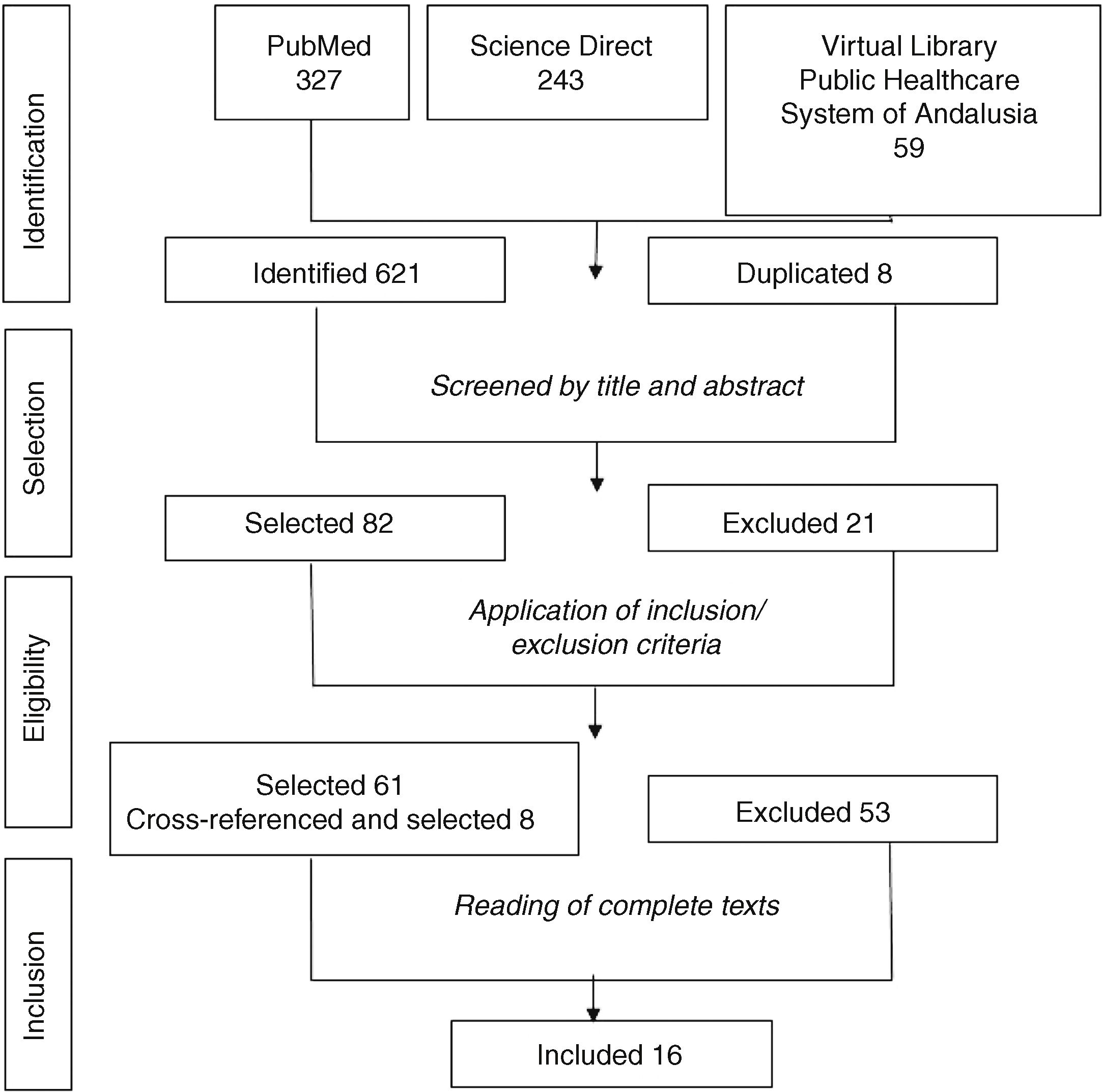

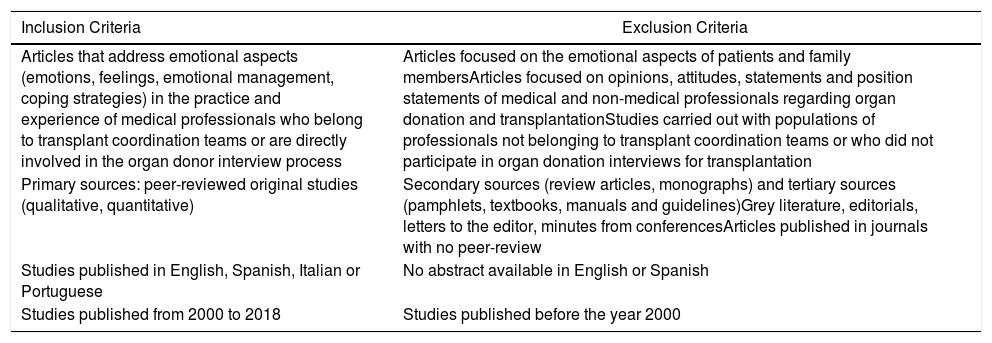

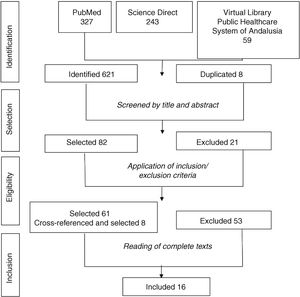

The search process was carried out independently by 2 researchers. The pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1. After the identification of the articles, the duplicate sources were eliminated and a pre-selection, selection and analytical process were conducted in 4 phases. Fig. 2 describes the article selection and inclusion process.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Articles that address emotional aspects (emotions, feelings, emotional management, coping strategies) in the practice and experience of medical professionals who belong to transplant coordination teams or are directly involved in the organ donor interview process | Articles focused on the emotional aspects of patients and family membersArticles focused on opinions, attitudes, statements and position statements of medical and non-medical professionals regarding organ donation and transplantationStudies carried out with populations of professionals not belonging to transplant coordination teams or who did not participate in organ donation interviews for transplantation |

| Primary sources: peer-reviewed original studies (qualitative, quantitative) | Secondary sources (review articles, monographs) and tertiary sources (pamphlets, textbooks, manuals and guidelines)Grey literature, editorials, letters to the editor, minutes from conferencesArticles published in journals with no peer-review |

| Studies published in English, Spanish, Italian or Portuguese | No abstract available in English or Spanish |

| Studies published from 2000 to 2018 | Studies published before the year 2000 |

In the review process, the ENTREQ27 statement and the PRISMA-P28 protocol checklist were consulted, while a pre-established revision protocol was used to reduce the individual biases of the authors in order to favor transparency and the possibility of replicating the study. Likewise, an assessment was made of the quality and methodological validity of the quantitative and qualitative studies included in the review, based on the criteria established by the Joanna Briggs Institute,29 which led to the exclusion of articles that did not indicate the use of informed consent or approval by ethics committees, as well as those with insufficient descriptions of the methodology and sampling.

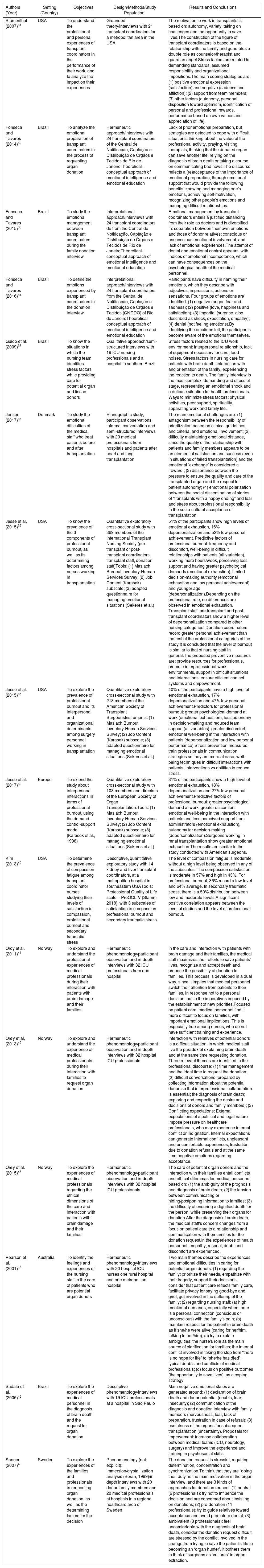

The sources selected for analysis were reviewed, extracting data from the article (title, authors, year of publication), location/country, objectives, design and methodology, participating population, results and most relevant conclusions. Subsequently, a narrative synthesis of the sources was undertaken, using inductive content analysis,30 which involved identifying and analyzing the main themes and categories of the information contained in the articles.

ResultsThe 16 articles reviewed31–46 were based on an exploratory and descriptive design; 12 used qualitative methodology31–36,41–46 and their main data collection technique was the interview. Content analysis was based on grounded theory and hermeneutic phenomenology, one of which was ethnographic.36 The 4 quantitative studies37–40 used the questionnaire, performed statistical analyses and focused on the prevalence of stress and emotional exhaustion in medical professionals and transplant coordinators.

Table 2 describes the design, objective and methodology of the 16 studies included in the review, as well as their main findings. After the analysis and the narrative synthesis of the references, 4 emerging themes were detected, which will be discussed below.

Description and Results of the Studies Included in the Review.

| Authors (Year) | Setting (Country) | Objectives | Design/Methods/Study Population | Results and Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blumenthal (2007)31 | USA | To understand the professional and personal experiences of transplant coordinators in the performance of their work, and to analyze the impact on their experiences | Grounded theory/interviews with 21 transplant coordinators for a metropolitan area in the USA | The motivation to work in transplants is based on: autonomy, variety, taking on challenges and the opportunity to save lives.The construction of the figure of transplant coordinators is based on the relationship with the family and generates a double role as counselor/therapist and guardian angel.Stress factors are related to: demanding standards, assumed responsibility and organizational impositions.The main coping strategies are: (1) positive emotional expression (satisfaction) and negative (sadness and affliction); (2) support from team members; (3) other factors (autonomy, personal disposition toward optimism, identification of personal and professional rewards, performance based on own values and appreciation of life). |

| Fonseca and Tavares (2014)32 | Brazil | To analyze the emotional preparation of transplant coordinators in the process of requesting organ donation | Hermeneutic approach/interviews with 24 transplant coordinators of the Central de Notificação, Captação e Distribuição de Órgãos e Tecidos de Rio de JaneiroTheoretical-conceptual approach of emotional intelligence and emotional education | Lack of prior emotional preparation, but strategies are detected to cope with difficult situations: thinking about the value of the professional activity, praying, visiting therapists, thinking that the donated organ can save another life, relying on the diagnosis of brain death or taking a course on communicating bad news.The discourse reflects a (re)acceptance of the importance of emotional preparation, through emotional support that would provide the following benefits: knowing and managing one's emotions, achieving self-motivation, recognizing other people's emotions and managing difficult relationships. |

| Fonseca and Tavares (2015)33 | Brazil | To study the emotional management between transplant coordinators during the family donation interview | Interpretational approach/interviews with 24 transplant coordinators de from the Central de Notificação, Captação e Distribuição de Órgãos e Tecidos de Río de JaneiroTheoretical-conceptual approach of emotional intelligence and emotional education | Emotional management by transplant coordinators entails a justified distancing from their role as doctors and is diversified in: separation between their own emotions and those of donor relatives; conscious or unconscious emotional involvement; and lack of emotional experiences.The attempt of denial and emotional control appears, with indices of emotional incompetence, which can have consequences on the psychological health of the medical personnel. |

| Fonseca and Tavares (2016)34 | Brazil | To define the emotions experienced by transplant coordinators in the donation interview | Interpretational approach/interviews with 24 transplant coordinators from the Central de Notificação, Captação e Distribuição de Órgãos e Tecidos (CNCDO) of Río de JaneiroTheoretical-conceptual approach of emotional intelligence and emotional education | Participants have difficulty in naming their emotions, which they describe with adjectives, impressions, actions or sensations. Four groups of emotions are identified: (1) negative (anger, fear and sadness); (2) positive (love, happiness and satisfaction); (3) impartial (surprise, also described as shock, expectation, empathy); (4) denial (not feeling emotions).By identifying the emotions felt, the participants become aware of the emotions themselves. |

| Guido et al. (2009)35 | Brazil | To know the situations in which the nursing team identifies stress factors while providing care for potential organ and tissue donors | Qualitative approach/semi-structured interviews with 19 ICU nursing professionals and a hospital in southern Brazil | Stress factors related to the ICU work environment: interpersonal relationship, lack of equipment necessary for care, loud noises. Stress factors in nursing care for patients with brain death: interaction with and orientation of the family, experiencing the reaction to death. The family interview is the most complex, demanding and stressful stage, representing an emotional shock and a delicate situation for health professionals. Ways to minimize stress factors: physical activities, peer support, spirituality, separating work and family life. |

| Jensen (2017)36 | Denmark | To study the emotional difficulties of the medical staff who treat patients before and after transplantation | Ethnographic study, participant observations, informal conversation and semi-structured interviews with 20 medical professionals from hospitals and patients after heart and lung transplantation | The main emotional challenges are: (1) antagonism between the responsibility of prioritization based on clinical guidelines and criteria, and emotional involvement; (2) difficulty maintaining emotional distance, since the quality of the relationship with patients and family members appears to be an element of satisfaction and success (even in situations of failed transplantation) and the emotional ‘exchange’ is considered a ‘reward’; (3) dissonance between the pressure to ensure the quality and care of the transplanted organ and the respect for patient autonomy; (4) emotional polarization between the social dissemination of stories of “transplants with a happy ending” and fear and stress about professional responsibility in the socio-cultural acceptance of transplantation. |

| Jesse et al. (2015)37 | USA | To know the prevalence of the 3 components of professional burnout, as well as its determining factors among nurses working in transplantation | Quantitative exploratory cross-sectional study with 369 members of the International Transplant Nursing Society (pre-transplant or post-transplant coordinators, transplant staff, donation staff)Tools: (1) Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey; (2) Job Content (Karasek) subscale; (3) adapted questionnaire for managing emotional situations (Sekeres et al.) | 51% of the participants show high levels of emotional exhaustion, 16% depersonalization and 52% low personal achievement. Predictive factors of professional burnout: frequency and discomfort, well-being in difficult relationships with patients (all variables), working more hours/week, perceiving less support and having greater psychological demands (emotional exhaustion), limited decision-making authority (emotional exhaustion and low personal achievement) and younger age (depersonalization).Depending on the professional role, no differences are observed in emotional exhaustion. Transplant staff, pre-transplant and post-transplant coordinators show a higher level of depersonalization compared to other nursing categories. Donation coordinators record greater personal achievement than the rest of the professional categories of the study.It is concluded that the level of burnout is similar to that of nursing staff in general.The proposed preventive measures are: provide resources for professionals, promote interprofessional work environments, support in difficult situations and interactions, ensure efficient contact systems and empowerment. |

| Jesse et al. (2015)38 | USA | To explore the prevalence of professional burnout and its interpersonal and organizational determinants among surgery personnel working in transplantation | Quantitative exploratory cross-sectional study with 218 members of the American Society of Transplant SurgeonsInstruments: (1) Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey; (2) Job Content (Karasek) subscale; (3) adapted questionnaire for managing emotional situations (Sekeres et al.) | 40% of the participants have a high level of emotional exhaustion, 17% depersonalization and 47% low personal achievement.Predictors for professional burnout: greater psychological demand at work (emotional exhaustion), less autonomy in decision-making and reduced team support (all variables), greater discomfort, emotional well-being in the interaction with patients (depersonalization and low personal performance).Stress prevention measures: train professionals in communication strategies so they are more at ease, well-being techniques in difficult interactions with patients, interventions vs abilities to reduce stress. |

| Jesse et al. (2017)39 | Europe | To extend the study about interpersonal interactions in terms of professional burnout, using the demand-control-support model (Karasek et al., 1998) | Quantitative exploratory cross-sectional study with 108 members and directors of the European Society of Organ Transplantation.Tools: (1) Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey; (2) Job Content (Karasek) subscale; (3) adapted questionnaire for managing emotional situations (Sekeres et al.) | 31% of the participants show a high level of emotional exhaustion, 18% depersonalization and 27% low personal achievement.Predictive factors of professional burnout: greater psychological demand at work, greater discomfort, emotional well-being in the interaction with patients and less perceived support from administrators (emotional exhaustion), autonomy for decision-making (depersonalization).Surgeons working in renal transplantation show greater emotional exhaustion.The results are similar to the study conducted with American surgeons. |

| Kim (2013)40 | USA | To determine the prevalence of compassion fatigue among transplant coordinator nurses, studying their levels of satisfaction in compassion, professional burnout and secondary traumatic stress | Descriptive, quantitative exploratory study with 14 kidney and liver transplant coordinators, at a metropolitan hospital in southeastern USATools: Professional Quality of Life scale – ProQOL-V (Stamm, 2018), with 3 subscales of satisfaction in compassion, professional burnout and secondary traumatic stress | The level of compassion fatigue is moderate, without a high level being observed in any of the subscales. The compassion satisfaction is moderate in 57% and high in 43%. For professional burnout, 36% record a low level and 64% average. In secondary traumatic stress, there is a 50% distribution between low and moderate levels.A significant positive correlation appears between the level of studies and the level of professional burnout. |

| Oroy et al. (2011)41 | Norway | To explore and understand the professional experiences of medical professionals during their interaction with patients with brain damage and their families | Hermeneutic phenomenology/participant observation and in-depth interviews with 32 ICU professionals from one hospital | In the care and interaction with patients with brain damage and their families, the medical staff maximizes their efforts to save patients’ lives, recognize and accept death and propose the possibility of donation to families. This process is developed in a dual way, since it implies that medical personnel switch their attention from patients to their families, in response not to a personal decision, but to the imperatives imposed by the establishment of new priorities.Focused on patient care, medical personnel find it more difficult to focus on families, with important emotional implications. This is especially true among nurses, who do not have sufficient training and experience. |

| Orøy et al. (2013)42 | Norway | To explore and understand the experience of medical professionals during their interaction with families to request organ donation | Hermeneutic phenomenology/participant observation and in-depth interviews with 32 hospital ICU professionals | Interaction with relatives of potential donors is a difficult situation, in which medical staff live the paradox of explaining brain death and at the same time requesting donation. Three relevant themes are identified in the professional discourse: (1) time management and the ideal time to request the donation; (2) difficult conversations (prepared by collecting information about the potential donor, so that interprofessional collaboration is essential; the diagnosis of brain death; exploring and respecting the desire and decisions of donors and family members); (3) Conflicting expectations: External expectations of a political and legal nature impose pressure on healthcare professionals, who may experience internal conflict or indignation. Internal expectations can generate internal conflicts, unpleasant and uncomfortable experiences, frustration due to donation refusals and at the same time negative emotions regarding acceptance. |

| Orøy et al. (2015)43 | Norway | To explore the experiences of medical professionals regarding the ethical dimensions of the care and interaction with patients with brain damage and their families | Hermeneutic phenomenology/participant observation and in-depth interviews with 32 hospital ICU professionals | The care of potential organ donors and the interaction with their families entail conflicts and ethical dilemmas for medical personnel based on: (1) the ambiguity of the prognosis and diagnosis of brain death; (2) the tension between communicating or hiding/postponing information to families; (3) the difficulty of ensuring a dignified death for the person, while preserving their organs for donation.After the diagnosis of brain death, the medical staff's concern changes from a focus on patient care to a relationship and communication with their families for the donation request.In the experiences of health personnel, empathy, respect, doubt and discomfort are experienced. |

| Pearson et al. (2001)44 | Australia | To identify the feelings and experiences of the nursing staff in the care of patients who are potential organ donors | Hermeneutic phenomenology/interviews with 20 hospital ICU nurses one rural hospital and one metropolitan hospital | Two main themes describe the experiences and emotional difficulties in caring for potential organ donors: (1) regarding the family: prioritize their needs, empathize with their tragedy, support their decisions, consider that patient care reflects family care, facilitate privacy for saying good-bye and grief, get involved in the suffering of the family; (2) regarding nursing staff: (a) high emotional demands, especially when there is a personal connection (conscious or unconscious) with the family's pain; (b) maintain respect for the patient in brain death as if she/he were alive (caring for her/him, talking to her/him); (c) try to explain ambiguities: the nurse's role as the main source of clarification for families; the internal conflict involved in taking the step from “there is no hope for life” to “she/he has died”; typical doubts and conflicts of medical professionals; (d) focus on positive outcomes (the opportunity to save lives), as a coping strategy. |

| Sadala et al. (2006)45 | Brazil | To explore the experiences of medical personnel in the diagnosis of brain death and the request for organ donation | Descriptive phenomenology/interviews with 19 ICU professionals at a hospital in Sao Paulo | Main negative emotional states are generated around: (1) declaration of brain death and donor potential (doubts, fear, insecurity); (2) communication of the diagnosis and donation interview with family members (nervousness, fear, lack of preparation, frustration in case of refusal); (3) usefulness of the organs for subsequent transplantation (uncertainty). Proposals for improvement: increase collaboration between medical teams (ICU, neurology, surgery) and improve the experience and training in psychosocial skills. |

| Sanner (2007)46 | Sweden | To explore the experiences of the families and professionals in requesting organ donation, as well as the determining factors for the decision | Phenomenology (not explicit): immersion/crystallization analysis (Boran, 1999)/in-depth interviews with 20 donor family members and 20 medical professionals at hospitals in a regional healthcare area of Sweden | The donation request is stressful, requiring determination, concentration and synchronization.To think that they are “doing their duty” is the main motivation in the organ interview, and there are 3 kinds of approaches for donation request: (1) neutral (6 professionals): try not to influence the decision and are concerned about insisting on donations; (2) pro-donation (11 professionals): try to guide relatives toward acceptance and avoid premature denial; (3) ambivalent (3 professionals): feel uncomfortable with the diagnosis of brain death, consider the donation request difficult, are stressed by the conflict involved in the change from trying to save the patient's life to becoming an ‘organ hunter’. It bothers them to think of surgeons as ‘vultures’ in organ extraction. |

The medical professionals described their professional experience on organ donation and transplantation teams as ‘exciting and, at the same time, exhausting’.31 The initial expectations described this work as ‘interesting and exciting’, ‘a difficult but rewarding challenge’ and the professional experiences were considered ‘different’, characterized by a certain solitude and isolation and, sometimes, little understanding by other professionals.31

The motivation to work in transplantation was based on personal needs and expectations as well as care requirements.31 The main challenges and difficulties reported include: working constantly with death, situations of suffering and grief, and in a psychologically and emotionally demanding setting.36

The essential qualities of persons working in the donation/transplantation process were: empathic, compassionate and positive-minded attributes; having the capability to maintain emotional distance and to develop relationship and communication skills.31

The Transition of Professional Roles: (Self)perceptions and MetaphorsThe use of different metaphors has appeared in the construction of the professional identity and the self-perception of medical professionals with regards to the donation-transplantation process. Medical staff members have been considered ‘therapists’ and, at the same time, ‘guardian angels’: the role of therapist was related to the support and companionship they provide, while the image of the guardian angel was based on their role as repositories of the trust of patients and their families.31

In the Danish study,36 medical professionals expressed their responsibility in the definition of ‘norms about life and death’, which the author termed guardians of ‘the gift’, based on the context of organ donation as an inevitably non-reciprocal act that implies a certain tyranny of ‘the gift’,47 described by Marcel Mauss as a complex social phenomenon (characterized by giving, receiving and ensuring reciprocity).

The Norwegian studies41–43 described how, in the care of potential donors and their families, ICU staff experienced a dual process of role migration, with important emotional implications: from the role of the patient's ‘lifeguard’ to the role of ‘organ claimant’. In this manner, the professional approach focused on the patient changed toward a family-centered approach, which was described in terms of ‘internal conflict’, ‘tension’, ‘ambiguity’, ‘paradoxical situation’ and ‘ambivalence’.42

This conflict of roles has also been reported by Swedish intensive medicine professionals, who explained how the passage from ‘lifeguards’ to ‘beggars of body parts’ or ‘organ hunters’ imposed significant emotional difficulties caused by the transition from the traditional role of providing patient care and consolation to families, toward the transgression of roles associated with the demand of organs of their recently deceased loved one.46 This emotional conflict was also identified by nurses of an Australian ICU at the time of communicating to families the brain death situation of their loved ones. The transition from transmitting hope for life to communicating the death of patients was especially difficult for all professionals.44

Emotional ExperiencesRelationship With (Potential) Donor PatientsThe main professional experience centered around responsibility. On the one hand, the commitment to caring for the patient's body31,44 and ensuring the fulfillment of their wishes in terms of organ donation and, on the other hand, the ethical dilemmas and emotional difficulties (doubts, fears, ambiguity) involved in establishing brain death, the dignified death of these patients and the preservation of their organs for their possible extraction.43

Relationship With Donor FamiliesStress factors identified include the difficulty of experiencing and managing the reactions of the family upon the death of their loved one,35 as well as the emotional costs associated with not being able to guarantee the utility and successful use of the organs donated. The professionals referred to the tacit commitment that is established with families around the meaning of donation to alleviate pain and suffering or give meaning to the death of the donor.31

In quantitative studies, 51% of nurses37 and 40% of transplant surgery specialists experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion in the United States38 and 31% in Europe.39 Stress factors indicated a higher level of emotional burnout37 and the psychological demands imposed by the relationship with family members or the communication of bad news generated more emotional exhaustion,37 depersonalization and low personal fulfillment.38

Other studies also addressed the compassion fatigue experienced by health professionals in the United States,40 which resulted in poor sleep quality or experiencing intrusive thoughts.31

The donation interview was identified by all medical professionals as the most delicate and important moment, a stage of great complexity35 that is demanding and stressful,35 a difficult and unpleasant situation that produced conflicting emotions42 or an emotional shock,35 requiring determination, concentration and synchronization.46

The main difficulties were related with planning and choosing the right moment to conduct the interview; the internal conflict determined by the possibility of (not) interfering with the family's decision and providing for a conscious and informed decision; and the internal and external expectations of professionals and the medical organization.42

The main emotions were categorized as: positive, negative, impartial and denial.34

The identified positive emotions included work satisfaction, love and happiness derived from: adequate and optimal attention given to families,31 the prioritization of their needs, empathy toward their tragedy, support for their decisions, respect for their privacy during their good-byes and mourning,44 understanding and the quality of the relationship with the family and, finally, obtaining consent for the donation.34

Negative emotions included: sadness and affliction31; doubt and discomfort43; fear of increasing the suffering of families and being perceived as ruthless and insensitive46; fear, disappointment and frustration in the face of failure.31 Situations involving pediatric patients, family demands for financial compensation and aggressive reactions were all especially associated with emotions of anger, fear and sadness.34

Involvement in the suffering of families44 and the projection and imaginary construction of similar experiences by medical personnel34 were fundamental determinants for negative emotional experiences.

Impartial emotions included surprise, shock, and expectation,34 as well as respect and empathy.43

Finally, the presence of denial was inferred, as expressed by professionals who did not describe any type of emotional experience.34

Relationship With Organ RecipientsThe decision regarding which patients would receive an organ, to whom to confer the hope of life, was significantly difficult, especially due to the presence of emotional, personal and family burden factors, all of which are intrinsically linked to the selection process for transplantation.36

In the care of organ recipients, satisfactory and positive emotional elements often appeared (the reward of successful transplantation, the gratitude of patients and relatives), but even the experiences of suffering and loss acquired a sense of useful experience and a source of knowledge. Negative emotions were also recorded, especially frustration, given the poor response to treatment or the lack of involvement of some patients in their own care.36

Relationship With the OrganizationThe stress factors identified by the medical personnel were: the sometimes difficult or conflictive relationship with hospital administrators, the pressure and demands imposed by the operation and organization of the system, and the administrative and legal requirements associated with the donation and transplant process.31

Relationship With SocietyThe medical personnel were aware of their participation in the representation and construction of the social image and acceptance of organ donation and transplantation. In addition, they considered themselves highly responsible for transmitting an image of optimism and hope around donations and transplantation. However, this process was sometimes experienced from the fear of failure, the pressure to minimize the media impact of sensitive or negative situations, and stress regarding the diffusion of sensitive information for public opinion.36

Strategies for Coping and Improving Emotional ManagementStrategies included: knowledge and emotional expression, peer support, identification of professional-type rewards and pursuit of personal well-being.

Regarding knowledge and emotional expression, the importance of emotional control was mentioned, as well as the search for the balance between negative and positive emotions.31 Emotional management was indicated as a common and useful strategy for self-motivation, the identification of other people's emotions and for overcoming difficult situations and experiences.32

Peer support was generated among medical personnel, based on trust and mutual understanding,31,35 as an efficient system of interrelationship and empowerment37 created mainly by the specificity and peculiarity of the work that make it a true ‘lifestyle’.31

Professional factors included autonomy and the ability to manage the cases of different donors,31 and the search for rewards that guarantee professional satisfaction. These give meaning and significance to the work done, while defining achievable and valuable objectives, acting in line with professional values, thinking about the usefulness of the work for saving lives31,32 or focusing on positive and successful elements.44

Elements of personal well-being showed a disposition toward optimism,31 living with spirituality,31,32,35 having a positive vision about the meaning of life, separating work from personal life, carrying out physical activities35 or seeking specialized psychological support.32,37 As measures to prevent stress and difficult situations, training activities aimed at providing resources and strategies for emotional management and communication skills were requested.32,37,38

DiscussionThis bibliographic review explored the main experiences and emotional experiences of medical personnel working in the field of organ donation and transplantation, based on results reflected by qualitative and quantitative studies published between 2000 and 2018, and concentrated in the United States, Brazil, Australia and Scandinavia.

Among the limitations of the study, it is worth highlighting the idiomatic bias in the selection and analysis and the difficulty in making comparisons and extrapolations to other areas and professional populations. However, the review also had strengths, associated mainly with the broad time span (2000–2018), the evaluation of the methodological quality and the added value of the narrative analysis that allowed key issues and concepts to be explored, analyzed and systematized.

The main finding of this literature review was the identification of important dilemmas, conflicts and contradictions in emotional experiences. Professional experiences suggested dual experiences and polarized perspectives that were able to dichotomically identify sources of positive assessment and satisfaction versus difficulties and stress factors, as well as positive versus negative emotions, for which medical personnel developed varied and disparate coping strategies.

The first source of contradiction originated from the description of the work and the qualities and professional roles exercised. On the one hand, there was a high degree of motivation and enthusiasm for the work carried out, which concurs with the results of other studies12 and with the ‘rewarding’ experience also identified in a recent systematic review about the functions and professional impact of organ donation.3 Their roles as ‘lifeguards’,41,43 ‘guardian angels’31 or ‘guardians of the gift’36 indicated a high level of responsibility and professional involvement, through positive metaphors with high professional, social and ethical value.

However, living with situations of pain, suffering and grief, and the psychological demands in the interaction and communication with patients and family, led to emotional exhaustion and professional burnout.3 Given this, the importance of training the sensitivity and adaptation of health personnel to the needs of patients and families was emphasized15,24,26 as well as to work on their sense of control and professional autonomy as measures to prevent burnout.48

Although this review validated organizational, legal and management difficulties,3,11 the greatest emotional challenge had mainly a relational and human dimension. The interaction with patients, family members, recipients, the rest of the team, managers and administrators or citizens in general, represented the grounds and at the same time the element of greatest impact and pressure on the experiences and emotional management of medical professionals.

The contact and experience with family members of potential donors, especially during the donation interview, were revealed as an emotional high point. Time management21 and the professional use of empathy,16,49 trust,21 active listening,13,19,20 sensitivity and compassion50 render the donation interview a complex and dramatic process,14 with important dilemmas and ethical conflicts for medical professionals.3

Regarding the request for donation, the main emotional discrepancy crystallized around the tensions experienced in different processes of role transition, functions and approaches. On the one hand, a change in the clinical and care approach was identified: from being focused on the donor patient and saving her/his life, to preserving the patient's organs for extraction. On the other hand, there is also a change in the model of interaction and affective communication with families: from a relationship based on information and companionship in feelings of expectation, uncertainty and hope, to the communication of death, while experiencing suffering and grief. Finally, the step from acceptance, respect and understanding of family pain toward the request and decision-making about the donation. In this process of multiple migration of roles and functions, professionals experienced a process of emotional adjustment that included anticipatory, confrontational and post-exposure confrontational elements.12 In addition, the variety of emotional management strategies—dependent on individual, professional and contextual characteristics11—also resulted in the development of different approaches to the request for donation. These could vary, depending on the use of relational/affective and clinical/efficient components, from a model focused on the needs of patients and relatives to a model focused on the organs and their utility.50 This was also described in the studies reviewed, which identified neutral, pro-donation and ambivalent approaches in the donation request.46

Finally, we should mention the heterogeneity of coping strategies used by medical professionals in emotionally difficult situations. In the first place, the usefulness of emotional expression was shown to be a mechanism for overcoming complicated moments, although the studies reviewed reported an underuse of emotional expression and frequent cases of emotional denial. In the available bibliography, we have found similar portrayals, such as ‘hiding behind a mask’, as described by nurses participating in organ extraction,1 thus avoiding highly emotional situations due to discomfort and apprehension,14 or not expressing emotions due to the fear of losing their image of professionalism.10

The results also revealed peer support as an emotional coping strategy and the need to improve the communication and quality of interprofessional relationships within the transplant coordination teams, a fact that is also documented in the literature.17,26

ConclusionThe bibliographic review reflected the complexity and plurality of the emotional experiences of medical personnel and the centrality of the interpersonal approach in the donation/transplantation process. The intense emotions of responsibility experienced at all levels, the perception of the work as a great challenge, and the search for rewards as the main coping strategy were all explanatory factors for the important contradictions and tension described in their roles and functions, which were especially relevant during the donation interview.

Based on this review, there is evidence of the need to carry out in-depth studies with medical professionals from transplant teams in order to design training strategies adapted to their needs and to improve their emotional experiences in the treatment process.

FundingNo funding received to complete this study.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Danet Danet A, Jimenez Cardoso PM. Vivencias y emociones profesionales en el proceso de donación y trasplantes de órganos. Una revisión sistemática. Cir Esp. 2019;97:364–376.