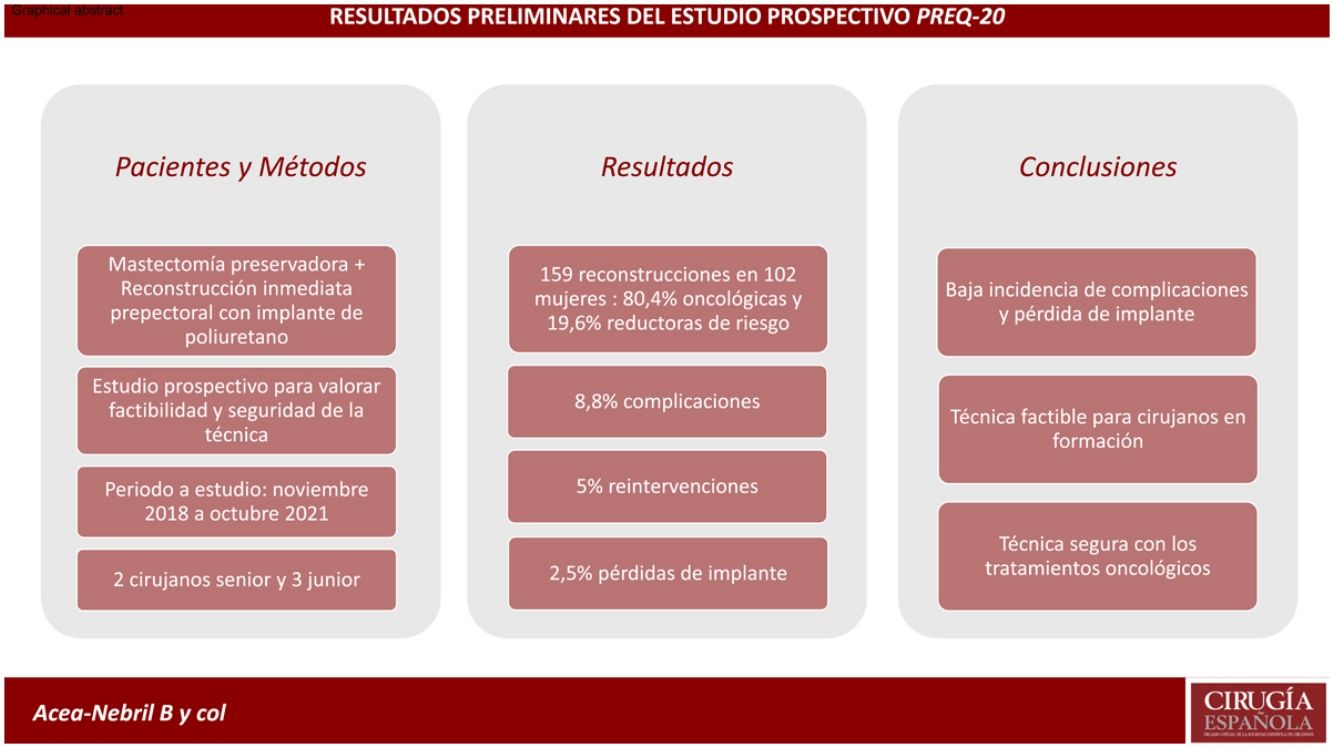

In recent years, mastectomy and reconstruction techniques have evolved towards less aggressive procedures, improving the satisfaction and quality of life of women. For this reason, mastectomy has become a valid option for both women with breast cancer and high-risk women. The objective of this study is to analyze the safety of mastectomy and immediate prepectoral reconstruction with polyurethane implant in women with breast cancer and risk reduction.

MethodObservational prospective study to evaluate the feasibility and safety of immediate reconstruction using prepectoral polyurethane implant. All women (with breast cancer or high risk for breast cancer) who underwent skin-sparing or skin-and-nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction with a prepectoral polyurethane implant were included. Women with breast sarcomas, disease progression during primary systemic therapy (PST), delayed, autologous or retropectoral reconstruction, and those who did not wish to participate in the study were excluded. Surgical procedures were performed by both senior and junior surgeons. All patients received the corresponding complementary treatments. All adverse events that occurred during follow-up and the risk factors for developing them were analyzed.

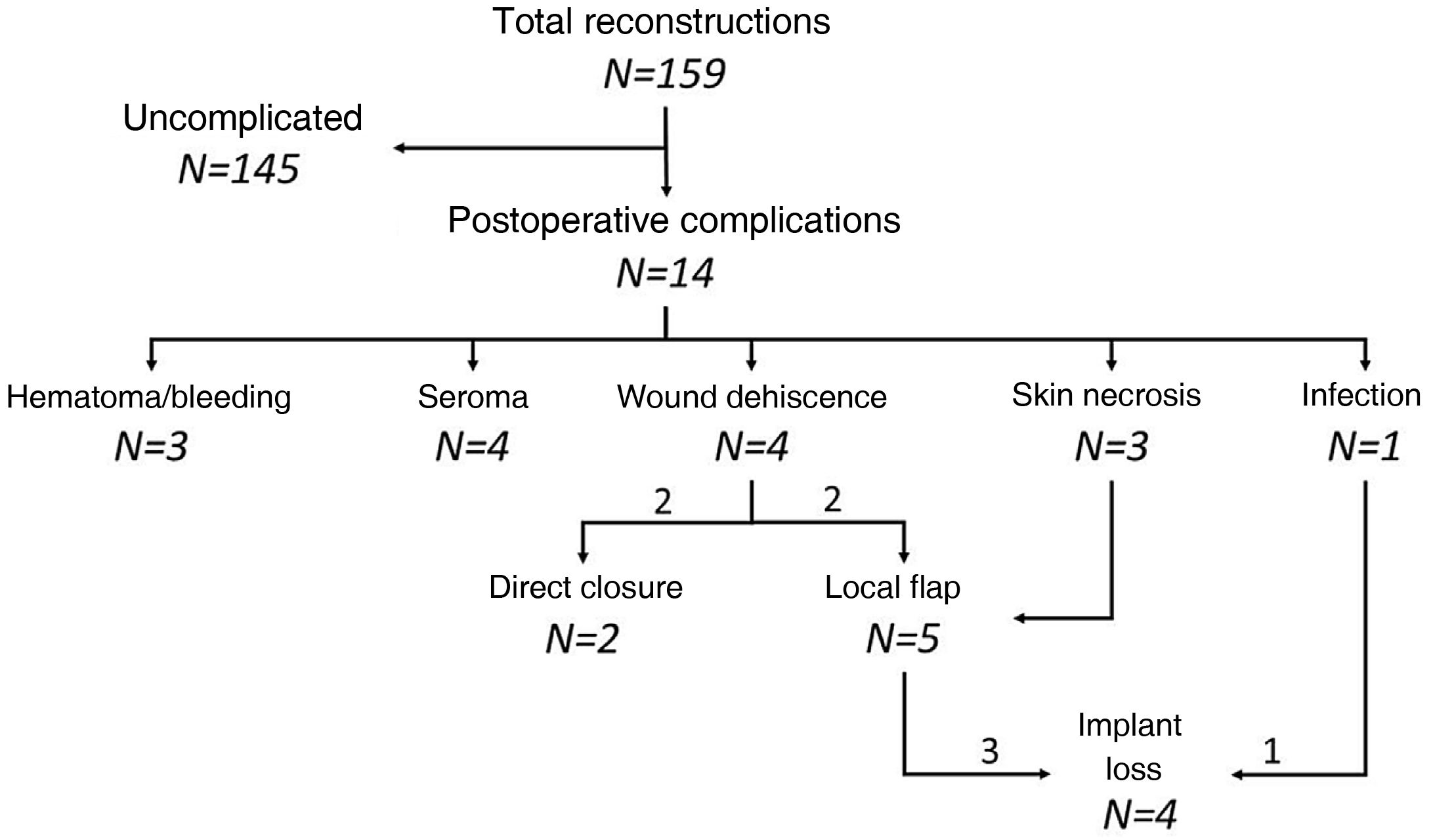

Results159 reconstructions were performed in 102 women, 80.4% due to breast carcinoma. Fourteen patients developed complications, the most frequent being seroma and wound dehiscence. Eight women required a reoperation (5.0%), seven of them due to implant exposure. Four reconstructions (2.5%) resulted in loss of the implant. Three patients progressed from their oncological process: a local relapse in the mastectomy flap, an axillary progression and a systemic progression.

ConclusionsPrepectoral reconstruction with a polyurethane implant is a procedure with a low incidence of postoperative complications (8.8%) and implant loss (2.5%). Its use is safe with perioperative cancer treatments (neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy).

Durante los últimos años las técnicas de mastectomía y reconstrucción han evolucionado hacia procedimientos menos agresivos, mejorando la satisfacción y calidad de vida de la mujer. Por ello, la mastectomía se ha convertido en una opción válida tanto para mujeres con cáncer de mama como en mujeres de alto riesgo. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar la seguridad de la mastectomía y reconstrucción inmediata prepectoral con implante de poliuretano en mujeres con cáncer de mama y reducción de riesgo.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo observacional para evaluar la factibilidad y seguridad de la reconstrucción inmediata mediante implante prepectoral de poliuretano. Se incluyeron todas las mujeres (con cáncer de mama o alto riesgo para cáncer de mama) intervenidas mediante una mastectomía preservadora de piel o piel y pezón con reconstrucción inmediata con implante de poliuretano prepectoral. Se excluyeron las mujeres con sarcomas de mama, progresión de la enfermedad durante el tratamiento sistémico primario (TSP), reconstrucción diferida, autóloga o retropectoral y aquellas pacientes que no desearon participar en el estudio. Los procedimientos quirúrgicos fueron realizados tanto por cirujanos senior como junior. Todas las pacientes recibieron los tratamientos complementarios correspondientes. Se analizaron todos los eventos adversos acontecidos durante el seguimiento y los factores de riesgo para desarrollarlos.

ResultadosSe realizaron 159 reconstrucciones en 102 mujeres, 80,4% por un carcinoma mamario. Catorce pacientes desarrollaron complicaciones, siendo el seroma y la dehiscencia de la herida las más frecuentes. Ocho mujeres precisaron una reintervención (5,0%), 7 de ellas por exposición del implante. Cuatro reconstrucciones (2,5%) culminaron con pérdida del implante. Tres pacientes presentaron progresión de su proceso oncológico: una recaída local en el colgajo de la mastectomía, una progresión axilar y una progresión sistémica.

ConclusionesLa reconstrucción prepectoral con implante de poliuretano es un procedimiento con una baja incidencia de complicaciones postoperatorias (8,8%) y pérdida de implante (2,5%). Su utilización es segura con los tratamientos perioperatorios oncológicos (quimioterapia neoadyuvante y radioterapia).

Mastectomy is currently a necessary surgical procedure in surgical oncology (SO) and risk reduction surgery (RRS). Several studies1–3 have shown that planning immediate reconstruction after mastectomy improves patient satisfaction and quality of life, therefore making it an option that should be discussed during the shared decision-making process with the patient.

In recent years, mastectomy and breast reconstruction techniques have evolved towards less aggressive procedures and greater preservation of anatomical elements. Thus, mastectomies aimed at immediate reconstruction pursue the preservation of the skin coverage of the breast, the inframammary fold and, occasionally, the nipple-areola complex (NAC). Reconstructive procedures also involve prepectoral placement of the breast implant, which has resulted in less postoperative morbidity and a more natural reconstruction. Initially, these prepectoral implants have been covered with a mesh (biological or synthetic) to improve their subcutaneous integration, although some authors4 have recently published the use of polyurethane implants (PI) to avoid the use of said mesh. In any case, several studies5,6 have shown that the association of a skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) with immediate prepectoral reconstruction (IPR) guarantees good results in both SO and RRS.

Despite these improvements, there are currently several unknowns about the safety of IPR in the contexts of SO and RRS. The objective of this study is to analyze the safety of mastectomy and IPR using PI in women with breast cancer and risk reduction surgery in terms of surgical complications and implant loss, as well as oncological safety and compatibility with adjuvant treatments. We therefore present the initial results of a prospective study by our breast unit.

MethodsProspective observational study to evaluate the feasibility and safety of IPR using PI in high-risk female patients with breast cancer who underwent surgery from November 2018 to October 2021. The study has been assessed and approved by the hospital’s healthcare ethics committee with code PreQ-20 and reference number 2020/295. Subsequently, the study protocol was registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov website (code NCT046425087)7.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Our study included women of legal age who underwent SSM or skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomies (SNSM), either unilateral or bilateral, and IPR with PI. The study population includes 2 groups of patients:

- -

Women with breast cancer. Patients with a diagnosis of breast carcinoma (invasive or ductal carcinoma in situ) who required a mastectomy as surgical treatment.

- -

Women at high risk for breast cancer. Women with hereditary syndrome for breast and ovarian cancer, with high-risk histological lesions associated with a family history or previous diagnosis of breast carcinoma who have been diagnosed as high-risk for breast cancer during their follow-up. These patients were also evaluated in the high-risk consultation, and their RRS have been approved by the tumor committee.

Patients excluded from the study were those with breast sarcomas, disease progression during primary systemic therapy (PST), deferred/autologous/retropectoral reconstruction, and patients who did not wish to participate in the study. Autologous reconstruction was performed in women with a previous mastectomy and wall radiation therapy, who underwent deferred reconstruction. Retropectoral reconstruction was indicated in patients who required extensive resection of skin tissue, whose skin remnant could not provide coverage for an implant.

Preoperative evaluation. All patients were evaluated by the surgical team of the unit that indicated the preserving mastectomy, who assessed the viability for each patient. Subsequently, this proposal was approved by the multidisciplinary breast committee. In addition to the mammography and ultrasound study, all study patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to confirm tumor size and dispersion, while also assessing the distribution of the glandular tissue, subcutaneous fat, and subclavicular and sternal fat transitions.

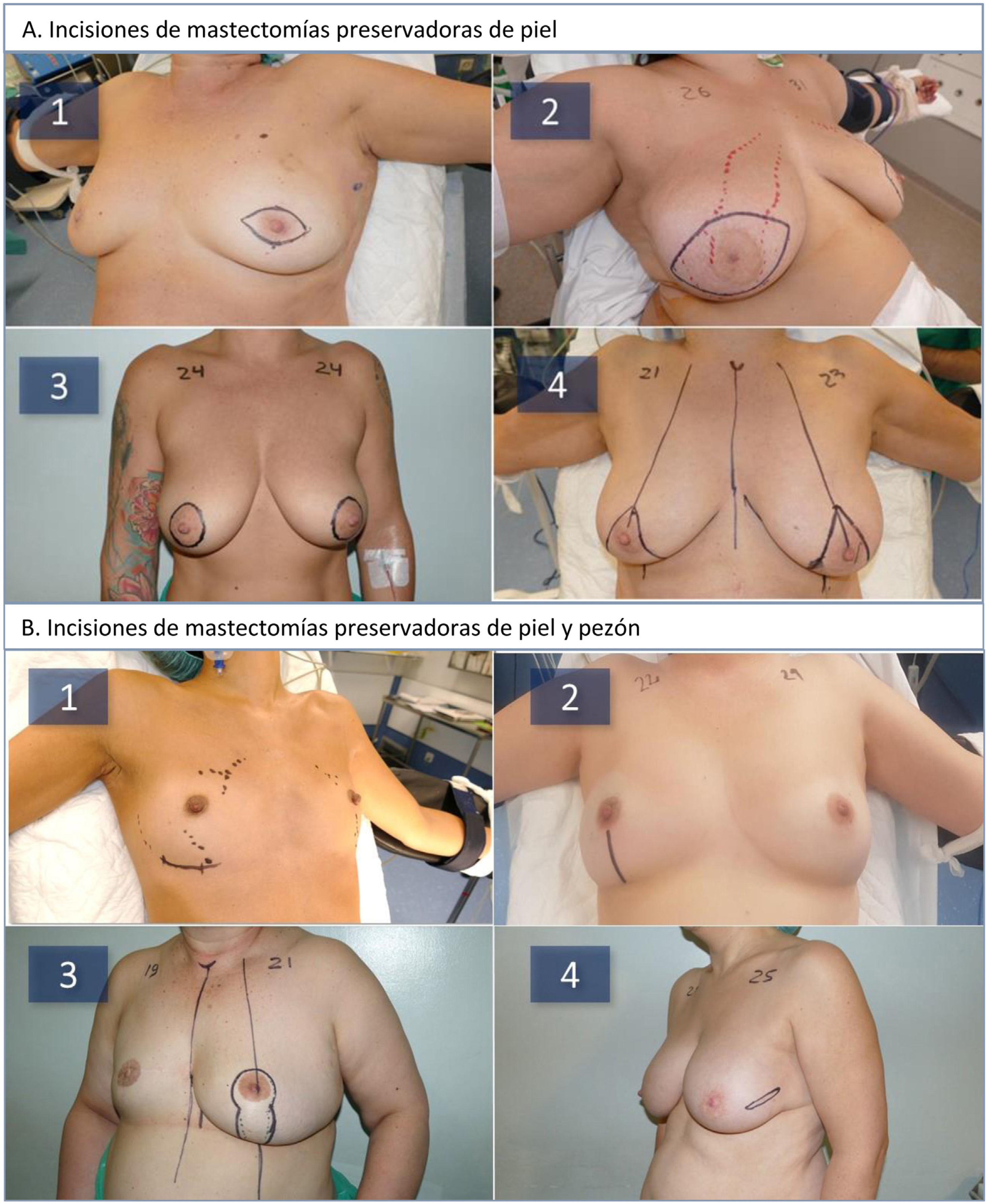

Surgical method. Either SSM or SNSM was performed in all patients, depending on the anatomical characteristics of the breast (volume, ptosis), the oncological process (location, distance from the skin, and NAC) and according to the criteria set forth by Nava et al.8 (Fig. 1A). According to these criteria, patients with small or medium breast volumes were treated with SNSM, except if the neoplastic process prevented it or if the distance from the NAC to the sternal notch was greater than 25 cm. Patients with voluminous breasts were treated with a Carlson type 4 SSM9. The inframammary incision was used in women with small/moderate breasts, the vertical incision at women with moderate-sized breasts, and the vertical pattern at women with breast ptosis (Fig. 1B). Mastectomy was performed based on the distribution of the neoplastic process in cancer patients and the distribution of subcutaneous fat observed in the preoperative MRI. The thickness of the skin flap was evaluated according to the Rancati classification (“Breast tissue coverage classification”)10: 1 cm for type 1; 2−3 cm for type 2; 3 or more centimeters for type 3, and it was given shape according to the specific anatomy of each patient and the tumor location. In patients with tumors close to the skin flap, titanium clips were left to mark the location of the neoplastic process. In SNSM, the retroareolar tissue was cleaned using the Folli technique11. In cancer patients, an intraoperative biopsy was carried out at the base of the nipple, which was removed when neoplastic involvement was demonstrated. Breast reconstruction was performed with placement of a polyurethane foam-coated silicone implant (Microthane™, POLYTECH Health & Aesthetics, Dieburg, Germany) in the prepectoral position. In all cases, antibiotic prophylaxis was administered with intravenous cefazolin during the first 24 h, and a suction drain was inserted.

A: Types of skin-sparing mastectomies (SSM) used during the study: periareolar spindle-shaped (1), central spindle-shaped (2), tabaco pouch (3), Carlson type 4 inverted T pattern (4). B: Types of skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomies (SNSM) used during the study: inframammary fold (1), inferior vertical (2), vertical pattern (3), lateral (4).

All mastectomies and reconstructions were performed by our unit’s 5 surgeons/gynecologists (2 seniors and 3 juniors) or by residents under supervision. One of the senior surgeons was in charge of supervising the surgical procedures and guiding the treatment of complications.

Postoperative care. All patients were hospitalized for at least 24 h. The day after the intervention, the absence of hematoma was confirmed, and patients were recommended to use a t-shirt without the need for a compression bra. The suction drain was removed when the discharge was less than 50 mL/d.

Complementary treatments. The treatments were agreed upon by the multidisciplinary committee according to the clinical guidelines. In patients with tumors that expressed hormone receptors, hormone therapy was indicated for 5–10 years. Patients who required chemotherapy treatment (primary or adjuvant) completed a sequential regimen of adriamycin and cyclophosphamide, followed by paclitaxel. In those patients with Her2 overexpression, trastuzumab and pertuzumab were prescribed.

Patients with tumors larger than 4 cm and/or lymph node involvement received radiotherapy of the chest wall and/or lymph node chains. Those patients with microscopic involvement of the superficial margin of the mastectomy were evaluated by the committee for extended excision of the subcutaneous tissue or to perform radiotherapy treatment.

Postoperative follow-up. Patients were evaluated weekly during the first month for the early detection of complications. Subsequently, follow-up was carried out every six months in cancer patients and annually in RRS. All patients underwent a breast MRI one year after the intervention to assess residual glandular tissue.

Definition of complications. We analyzed the immediate complications (first 3 months after surgery) related to the mastectomy technique and reconstruction.

- -

Postoperative bleeding. Appearance of any amount of blood during the first 7 postoperative days that modified hospital admission (prolongation of stay or reoperation).

- -

Seroma. Accumulation of periprosthetic fluid that required maintaining the drain for more than 10 days or required the placement of a new drain.

- -

Infection. Need for antibiotics in the first 30 postoperative days, excluding antibiotic prophylaxis.

- -

Wound dehiscence. Separation of the edges of a surgical wound that required action by the surgeon.

- -

Cutaneous necrosis. This was defined as the appearance of areas of skin without vascularization that conditioned cell death. All necroses that appear during the first 3 months after surgery and required some intervention (appointment in consultation or in the operating room) are included.

- -

Loss of the implant. Need to remove the prosthesis for any reason.

Calculation of the sample size. Assuming 5% implant loss, with a 95% confidence level and 5% precision, and assuming 10% possible loss during follow-up, we estimated a sample size of 81 patients.

Statistical analysisWe carried out a descriptive analysis of the variables included in the study. All quantitative variables are expressed with their mean and standard deviation. The qualitative variables are expressed in proportions and their respective confidence intervals. Means were compared using the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis test or ANOVA, as appropriate, after confirming the normality of the variables with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The association of qualitative variables was estimated using the chi-square statistic. The statistical analysis was performed using version 24 of the IBM SPSS statistical program and Epidat 4.1.

ResultsDuring the study period, 159 reconstructions were performed in 102 women. A total of 82 (80.4%) underwent surgery for breast carcinoma, while mastectomy was indicated in 20 (19.6%) due to high personal or genetic risk (Table 1). Bilateral mastectomy was performed in 57 patients (55.9%), 4 of them due to bilateral mammary carcinoma and in the remaining 53 women due to risk reduction. No statistically significant differences were observed in age, BMI or clavicle-NAC distance between SO and RRS. The most frequent mutation was in the BRCA1 gene (14.7%).

Clinical characteristics of the patients.

| Patients | Oncological | Risk reduction | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 102 | N = 82 | N = 20 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Cause of mastectomy | ||||

| Oncological | 43 (42.2) | 43 (52.4) | – | – |

| Oncological/risk reduction | 39 (38.2) | 39 (47.5) | – | |

| Risk reduction | 20 (19.6) | – | 20 (100) | |

| Bilateral mastectomy | 57 (55.9) | 43 (52.4) | 14 (70) | .156 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean | 46.8 ± 7.8 | 46.9 ± 7.5 | 46.7 ± 9.1 | .676 |

| Range | 30−67 | 30−65 | 33−67 | |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | ||||

| Mean | 23.9 ± 4.4 | 24.2 ± 4.6 | 22.5 ± 2.1 | .368 |

| Range | 17.8−42.1 | 17.8−42.1 | 19.5−26.1 | |

| Distance sternum/NAC (cm) | ||||

| Right breast | ||||

| Mean | 19.9 ± 2.9 | 20.0 ± 2.9 | 19.3 ± 2.6 | .528 |

| Range | 15−28 | 15−28 | 16−24 | |

| Left breast | .337 | |||

| Mean | 20.1 ± 3.1 | 20.3 ± 3.2 | 19.2 ± 2.6 | |

| Range | 15−31 | 15−31 | 16−24 | |

| Genetic study | ||||

| Not solicited | 4 (39.2) | 38 (46.3) | 2 (10) | |

| BRCA1 | 15 (14.7) | 5 (6.1) | 10 (50) | – |

| BRCA2 | 9 (8.8) | 4 (4.9) | 5 (25) | |

| PALB2 | 3 (2.9) | 3 (3.7) | 0 (0) | |

| RAD51 | 1 (1) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Negative | 22 (21.5) | 19 (23.2) | 3 (15) | |

| Pending result | 12 (11.8) | 12 (14.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Previously radiated breast | 14 (13.7) | 9 (10.9) | 5 (25) | .142 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | .353 |

NAC: nipple-areola complex; BMI: body mass index.

Surgical description. SNSM was the most used type of mastectomy (69.8%) in both SO (68%) and RRS (76.5%). The most used incisions were the inframammary approach (34.6%) and the vertical incision (34.6%) (Table 2), while 13.7% of the patients presented previous irradiation of the breast after lumpectomy. The mean duration of surgery was 187 min (SD: ±62.5), which was significantly longer in bilateral mastectomies. Surgical time was significantly higher in unilateral oncological mastectomy than in unilateral mastectomy due to risk reduction (P = .007). The mean weight of the surgical specimens was 290.6 g (±230.3), with no differences between groups. Mean hospital stay was 1.9 days (±0.8), with no differences between groups.

Surgical characteristics of the whole series.

| Reconstructions | Oncological reconstructions | Risk reduction reconstructions | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 159 | N = 125 | N = 34 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Type of mastectomy | ||||

| SSM type I | 23 (14.5) | 19 (15.2) | 4 (11.8) | .515 |

| SSM type IV | 25 (15.7) | 21 (16.8) | 4 (11.8) | |

| SNSM vertical | 55 (34.6) | 46 (36.8) | 9 (26.5) | |

| SNSM type II (lateral) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| SNSM inframammary fold | 55 (34.6) | 38 (30.4) | 17 (50) | |

| Surgical time (min) | ||||

| Mean | 165 ± 58 | 168.6 ± 55.1 | 153.2 ± 64.5 | .196 |

| Range | 55−330 | 75−330 | 55−300 | |

| Bilateral surgical time | .507 | |||

| Mean | 187.5 ± 62.5 | 192.1 ± 60.2 | 178.1 ± 61.8 | |

| Range | 100−330 | 100−330 | 110−300 | .007 |

| Unilateral surgical time | ||||

| Mean | 138.4 ± 38.4 | 144.5 ± 36.5 | 99.2 ± 27.9 | |

| Range | 55−240 | 75−240 | 55−120 | |

| Size of surgical specimen (g) | ||||

| Mean | 290.6 ± 230.3 | 318.3 ± 250.9 | 216.9 ± 102.8 | .123 |

| Range | 50−1660 | 50−1660 | 90−500 | |

SSM: skin-sparing mastectomy; SNSM: skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomy.

Oncology patients. Table 3 shows the pathological characteristics of the patients operated on for breast carcinoma. PST was administered in 30.5% of the patients, and 39% received radiation therapy of the chest wall after reconstruction. Infiltrating ductal carcinoma was the most frequent histological type (73.2%), and the most common subtype was luminal B Her2 negative (36.6%). Tumor presentation was multifocal in 40.2% of the patients and multicentric in 25%. The pathological study showed involvement of the superficial margin of the mastectomy in 10 patients (12.1%), and in 8 of these patients the involvement was focal and did not require surgical expansion. The other 2 patients had extensive involvement of the margin and required widening of the surgical margin guided by marking clips. Seven of these 10 patients received radiotherapy on the chest wall. In 5 women (6.1%), there was evidence of involvement of the base of the nipple, requiring its removal (3 in a deferred manner).

Clinical characteristics of patients with breast cancer.

| Patients | |

|---|---|

| N = 82 | |

| n (%) | |

| Histological type | |

| DCIS | 11 (13.4) |

| IDC | 60 (73.2) |

| ILC | 11 (13.4) |

| Dispersion | |

| Unifocal | 28 (34.1) |

| Multifocal | 33 (40.2) |

| Multicentric | 21 (25.7) |

| Tumor size (cm) | |

| Mean | 2.1 ± 1.8 |

| Range | 0−9 |

| Tumor size (TNM) | |

| Tiss | 10 (12.2) |

| T1a | 5 (6.1) |

| T1b | 11 (13.4) |

| T1c | 10 (24.4) |

| T2 | 22 (26.8) |

| T3 | 4 (4.9) |

| Tx | 10 (12.2) |

| Axillary involvement (TNM) | |

| N0 | 50 (60.9) |

| N1 | 22 (26.8) |

| N2 | 4 (4.9) |

| N3 | 3 (3.7) |

| Not assessable | 3 (3.7) |

| Tumor subtype | |

| Luminal A | 18 (22.0) |

| Luminal B Her2− | 30 (36.6) |

| Luminal B Her2+ | 11 (13.4) |

| Her2+ | 1 (1.2) |

| Triple negative | 12 (14.6) |

| Not valid | 10 (12.2) |

| Metachronous tumor | 9 (11.0) |

| Complementary treatment | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 25 (30.5) |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 24 (29.3) |

| Radiotherapy | 32 (39.0) |

| Hormone therapy | 59 (71.9) |

| Anti-Her2 | 12 (14.6) |

| Margins | |

| Free (>2 mm) | 64 (78.0) |

| <1 mm | 3 (3.7) |

| Focal contact | 8 (9.8) |

| Extensive contact | 2 (2.4) |

| Nipple involvement | 5 (6.1) |

IDC: invasive ductal carcinoma; DCIS: carcinoma ductal in situ; ILC: invasive lobular carcinoma.

Complications. The mean follow-up of the series was 11 months (range: 1–34 months), during which 14 patients presented postoperative complications (8.8% of the reconstructions). Seroma and wound dehiscence were the most frequent complications (Table 4). All the dehiscences occurred in cancer patients and in mastectomies with a vertical incision (3 type IV mastectomies and one with a vertical incision). Eight women required re-operation (5% of reconstructions), 7 of them due to implant exposure as a result of skin necrosis, wound dehiscence, or implant infection. Two cases of skin necroses affected previously irradiated patients. In 5 out of the 7 implant exposures, local flaps were used for coverage, which were effective in 3 patients. Four reconstructions (2.5%) culminated in loss of the implant, 3 due to contamination of the implant that was not resolved with the local flap and another for the continuation of adjuvant chemotherapy (Fig. 2).

Complications.

| Reconstructions | Oncological reconstructions | Risk reduction reconstructions | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 159 | N = 125 | N = 34 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Complications | 14 (8.8) | 11 (8.8) | 3 (8.8) | 1 |

| Type of complication | ||||

| Hematoma | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Seroma | 4 (2.5) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (5.9) | |

| Wound dehiscence | 4 (2.5) | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Skin necrosis | 3 (1.9) | 3 (2.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Bleeding | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Re-operation | 8 (5.0) | 7 (5.6) | 1 (2.9) | – |

| Cause of re-operation | ||||

| Implant exposure | 7 (4.4) | 7 (5.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Breast bleeding | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | – |

| Loss of implant | 4 (2.5) | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | – |

Oncological events. During follow-up, 3 patients presented progression of the oncological process: one local recurrence in the mastectomy flap 10 months after surgery due to a Her2 tumor, one axillary progression 6 months after mastectomy in a patient with a triple-negative tumor and PST with complete pathological response, and cerebral metastatic progression one month after surgery in a patient with a triple negative tumor who died 5 months later.

Follow-up. One year after the mastectomy, 24 of the 102 patients included in the study had a follow-up, and 2 of them (8.3%) presented a 1 cm layer of residual gland tissue.

In Fig. 3, we present the one-year evolution of patients who completed the reconstruction and complementary treatments. Fig. 3.1 presents a woman with a type IV bilateral skin-sparing mastectomy and her progress after nipple reconstruction and areola tattooing (Fig. 3.1C). Fig. 3.2 shows a patient with bilateral skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomy for an invasive carcinoma of the right breast with an indication for chest wall radiotherapy, and the result one year after completing radiotherapy (Fig. 3.2B). Lastly, we present a patient with extensive ductal carcinoma in situ of the right breast who underwent a skin- and nipple-sparing bilateral mastectomy, and after expansion of the retroareolar superficial margin of the right breast, she presented deformity of the right NAC and superficial necrosis of the left nipple (Fig. 3.3B). This deformity was resolved one year after surgery (Fig. 3.3C).

Evolution one year after surgery in patients with a skin-sparing mastectomy and prepectoral reconstruction: 3.1) patient with a type iv skin-saving mastectomy; 3.1C) evolution after reconstruction of the nipple and areola tattoo; 3.2A) patient with invasive carcinoma of the right breast with indication for chest wall radiation therapy; 3.2B) evolution one year after radiation therapy of the right chest wall; 3.3A) patient with extensive ductal carcinoma of the right breast; 3.3B) deformity of the right NAC after extension of the retroareolar superficial margin of the right breast; 3.3C) evolution one year after surgery.

Over the last 10 years, there have been scientific, healthcare and social changes that have made mastectomy the cornerstone of breast reconstruction and all its dimensions: oncological, quality of life and sustainability. On the one hand, advances in systemic treatment have led to better local control of the process and de-escalation in its initial clinical stage, enabling us to perform skin-preserving mastectomies with greater oncological safety. On the other hand, the Jolie Effect has promoted greater social awareness of the genetic risk in cancer, leading to an increase in genetic studies and RRS12. Finally, the evaluation of cosmetic results in women with breast reconstruction has revealed the expiration of reconstructive procedures, especially those linked to retropectoral implants, as well as differences in the satisfaction and quality of life of women13. The improvement of these results has focused on the use of ultra-conservative mastectomies, in order to provide a more stable and long-lasting anatomical structure in the reconstructed breast, and the use of prepectoral devices to reduce the local aggressiveness of the reconstructive procedure. In this context, conservative mastectomies have shown an oncological safety similar to modified radical mastectomy, as demonstrated by the meta-analyses by Lanitis et al.14 and De la Cruz et al.15, in which both SSM and SNSM did not present differences in oncological adverse events during the follow-up of patients in early stages of the disease. But this philosophy in the use of skin-sparing mastectomies aimed at reconstruction requires new approaches to increase safety, reduce cosmetic sequelae and improve patient perception. This requires preoperative evaluation of the individual possibilities for each breast to preserve anatomical elements, selection of a mastectomy technique adapted to the breast and, finally, assessment of the residual tissue after the surgical procedure. The PreQ-20 study has been designed to assess the safety of IPR using ultra-conservative mastectomies to learn about the satisfaction and quality of life reported by patients using the BreastQ questionnaire, and to assess cosmetic sequelae in the intermediate term.

PI have been considered macro-textured implants (ignoring the criteria of the International Organization for Standardization [ISO]16 classification, which does not classify them as such), and there have been warnings of a greater relationship with anaplastic giant cell lymphoma. However, like Hamdi17, we believe that PI cannot be considered macro-textured implants because the polyurethane foam that covers the silicone implant is a three-dimensional matrix that is incorporated into the shell and becomes, after a few years, an integral part of the implant capsule. Therein lies the reason for its low incidence of capsular contracture. Another parameter to explore in this discussion is the differences in the stability of the polyurethane foam. Clinical experience has shown that the degradation of this foam is different in the PI marketed by the 2 main manufacturers, and a higher number of cases with polyurethane delamination in has been observed with Silimed implants compared to Polytech devices. These differences may explain the low incidence of reported delamination and anaplastic giant cell lymphoma in Germany, where Polytech implants are manufactured and used extensively. The prospective study that is presented has selected the Polytech PI because it is currently authorized by the European and Spanish Medicines Agencies, and also to assess its impact on the safety of IPR.

There are currently 4 studies that have evaluated the use of PI in IPR4,18–20, all of which are retrospective. The study by De Vita et al.4 analyses the evolution of 21 patients operated on for RRS or SO, with a mean follow-up of 4 months. The studies by Coyette et al.18 and Salgarello et al.19 focused on the use of PI in women with RRS and concluded with a low incidence of postoperative complications and an acceptable score on the quality-of-life questionnaires, respectively. Finally, the study by Franceschini et al.20 retrospectively compares patients with breast cancer with retromuscular breast reconstruction and IPR with polyurethane. This study concludes that the placement of the PI in the prepectoral position associated with SNSM is safe and effective from an oncological standpoint; it is also simple to perform, reduces surgical time, reduces surgical complications and contributes to efficacy in maintaining costs versus the use of periprosthetic mesh. When these experiences are compared with others using synthetic mesh21–23 or biological mesh24–30 (Table 5), IPR with IP presented a lower incidence of implant infection and loss of the reconstruction. Thus, in the experiences with biological mesh, infection and loss of the implant can affect 1.9%–7.3% and 2.4%–10.2% of patients, respectively, while for synthetic mesh the incidence of infection has ranged from 0.8% to 6% and implant loss between 1.2%–8%. However, these data must be evaluated with caution since most of these studies are retrospective and show deficiencies in their methodology. PreQ-20 is currently the only study that prospectively evaluates the safety of IPR with PI, and the most notable datum is the low incidence of complications associated with the implant in the initial short-term follow-up. The low incidence of seroma and infection with PI may be related to the phenomenon of integration of the polyurethane foam into the subcutaneous tissue, which allows the implant to adhere and the tissue to grow within its three-dimensional structure. Another added advantage in the patients in this study was resistance to infection in cases with implant exposure due to dehiscence or skin necrosis. This characteristic has allowed the reconstruction to be maintained through the use of local flaps.

Postoperative complications in different series with prepectoral reconstruction.

| Author | N | Implant | Hematoma (%) | Seroma (%) | Wound dehiscence (%) | Skin necrosis (%) | Infection (%) | Implant loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ian Ng et al.21 | 50 | TiLOOP | 4.0 | 14.0 | – | 2.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 |

| Nguyen et al.22 | 63 | TiLOOP | 3.2 | 11.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 7.0 |

| Casella et al.23 | 250 | TiLOOP | 0.4 | – | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Baker et al.24 | 43 | Strattice | – | 2.3 | 8.1 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 4.7 |

| Urquia et al.25 | 136 | Cortiva | 2.2 | 2.2 | 0.7 | – | 7.3 | 10.2 |

| Ribuffo et al.26 | 207 | ADM | 1.4 | 4.3 | 1.9 | – | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| Highton et al.27 | 113 | ADM | – | 3.0 | – | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.4 |

| Sigalove et al.28 | 353 | ADM | – | 2.0 | – | 2.5 | 4.5 | – |

| Masiá et al.29 | 1450 | Braxon | 2.1 | 7.7 | 4.6 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 6.5 |

| Chandarana et al.30 | 406 | Braxon | 2.5 | 7.1 | 2.0 | 5.2 | 3.2 | 4.9 |

| de Vita et al.4 | 34 | Polyurethane | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salgarello et al.19 | 70 | Polyurethane | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Franceschini et al.20 | 82 | Polyurethane | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | 1.2 |

| Coyette et al.18 | 64 | Polyurethane | 3.1 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3.1(a) |

| Acea et al.* | 159 | Polyurethane | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

N: number of mastectomies.

The meta-analysis by Li et al.31 showed that IPR has a similar incidence of postoperative complications, implant loss and disease-free survival compared to retropectoral reconstruction. The PreQ-20 study shows that prepectoral reconstruction with IP is compatible with cancer treatments. In addition, PST with chemotherapy (30% of cancer patients in our study) has not led to an increase in postoperative complications or local recurrence. Recently, Wu et al.32,33 have shown that immediate reconstruction after SNSM in patients with primary chemotherapy has a similar incidence of local recurrence and overall survival compared to patients with mastectomy without reconstruction. Also, postmastectomy radiotherapy (39% of cancer patients in our series) has not been associated with an increase in complications or loss of the implant. Several authors6,34,35 have evaluated the impact of postoperative radiotherapy on IPR, with disparate results observed in the evolution of patients. Although the experience of Sigalove6 does not show relevant alterations in the evolution of the reconstructed breast, Sinnott et al.34 find a higher incidence of capsular retraction during follow-up that can affect up to 19% of patients. In the PreQ-20 study, the presence of capsular contracture was not detected in irradiated patients, possibly due to the short follow-up time.

This study has several limitations. First of all, the average follow-up of the series is insufficient to determine the oncological safety of prepectoral reconstruction with PI in oncological patients. In addition, the low rate of complications does not provide for the calculation of risk factors associated with each event. Finally, the absence of a control group precludes comparison of IPR with PI versus other surgical techniques or breast implants.

In conclusion, preliminary data from this prospective study confirm that IPR with PI is a procedure with a low incidence of postoperative complications (8.8%) and a low incidence of implant loss (2.5%). Cases of implant exposure can be managed through the use of local flaps, which in most cases will prevent loss of the reconstruction. In the oncological context, its use is safe in patients with PST as well as in those who require post-mastectomy radiation therapy. The low incidence of postoperative complications of PI in women with RRS indicates that this device is a good option in this clinical context.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.