SI: Minimally invasive surgery of the abdominal wall

Más datosThe repair of inguinal hernia is one of the most frequently performed surgeries in General Surgery units. The laparoscopic approach for these hernias will be clearly considered as the gold standard, based on its advantages over the open approach. There are no clear advantages of the transabdominal preperitoneal approach (TAPP) over the totally preperitoneal approach (TEP), although it has been shown to be more reproducible, presenting a shorter learning curve, although it presents more possibilities of developing trocar site hernias. Laparoscopic TAPP could be superior to TEP in the following indications: incarcerated hernias, emergencies, previous preperitoneal surgery, previous Pfanestiel-type incision, recurrent hernias, inguinoscrotal hernias and obese, being also a better alternative for females.

Robotic TAPP is a safe approach with similar results to laparoscopy; however, it is related to an increase in costs and operating time. The value of this technology for the repair of complex hernias (multiple recurrences, inguino-scrotal or after previous preperitoneal surgery) remains to be determined, since they represent a certain challenge for the conventional laparoscopic approach. On the other hand, robotic repair of inguinal hernias may be a way to reduce the learning curve before addressing complex ventral hernias.

Finally, artificial intelligence applied to the laparoscopic approach to inguinal hernia will undoubtedly have a significant impact in the future especially to determine the best the indications for this approach, on the performance of a safer technique, on the correct selection of meshes and fixation mechanisms, and on learning curve.

La reparación quirúrgica de la hernia inguinal es una de las intervenciones realizadas con mayor frecuencia en los servicios de Cirugía General. El abordaje laparoscópico de la hernia inguinal tiene un gran futuro como procedimiento gold estándar debido a sus ventajas sobre el abordaje abierto. No existen claras ventajas del abordaje transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) sobre el totalmente preperitoneal (TEP), aunque ha demostrado ser es más reproducible, presentando una menor curva de aprendizaje, aunque presenta más posibilidades de desarrollar hernias post-trócares. El TAPP laparoscópica podría ser superior al TEP en las siguientes indicaciones: hernias incarceradas, urgencias, cirugía previa preperitoneal, incisión previa tipo Pfanestiel, hernias recidivadas, hernias inguino-escrotales, obesos, pudiéndose tambien discutir su preferencia también en mujeres.

El TAPP robótico es un abordaje seguro con resultados similares que el abordaje laparoscópico; sin embargo, puede suponer un incremento de costes y del tiempo operatorio. Queda por determinar su valor de esta tecnología para la resolución de hernias complejas (multirecidivadas, inguino-escrotales o tras cirugía previa preperitoneal), que suponen cierto desafío para el abordaje laparoscópico convencional. Por otra parte, la reparación de las hernias inguinales por vía robótica puede suponer una forma de disminuir la curva de aprendizaje antes de abordar hernias ventrales complejas.

Por último, la inteligencia artificial aplicada al abordaje laparoscópico de la hernia inguinal tendrá sin duda un importante impacto en las indicaciones de la técnica, en la realización de una técnica más segura, en la correcta selección de las mallas y los mecanismos de fijación y en el aprendizaje de la misma.

Surgical repair of inguinal hernia is one of the most frequently performed interventions in general surgery services and there is now a wide variety of surgical techniques to resolve this condition.

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is a procedure increasingly used worldwide due to its excellent results.1 In the international guidelines for the treatment of inguinal hernia, experts recommend the laparoscopic approach as one of the best options, even for unilateral inguinal hernia in the male.1 Even so, and although the advantages of the minimally invasive approach have been demonstrated, it is still recommended that each case be individualised in order to choose the best technique based on the characteristics of each patient and type of hernia.

Due to the shorter hospital stay, less postoperative pain, and faster patient recovery, minimally invasive techniques are progressively gaining ground in many centres and are beginning to be considered the standard treatment for inguinal hernia where indicated.1,2 Due to cost constraints and hospital bed requirements associated with patient requests, hernia operations are increasingly performed in major outpatient surgery settings, and the laparoscopic technique has proven safe and feasible with this type of circuit.2

Among the major drawbacks traditionally associated with the laparoscopic approach were the need for general anaesthesia, the learning curve, and the costs associated with the technique in terms of material, mesh, and fixation mechanisms. However, with the passage of time and the standardisation of laparoscopic surgical techniques, we have seen that past differences in relation to the conventional open technique have practically disappeared, as we have observed a reduction in the cost of the material used, so that, together with a shorter hospital stay, less postoperative pain, and a faster recovery, the initially higher costs of the minimally invasive procedure have practically disappeared.3

Laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia is performed either using a totally preperitoneal approach (TEP) or the transabdominal preperitoneal approach (TAPP). Both techniques have shown similar results in terms of complications and recurrence, although the TAPP technique is more reproducible, with a shorter learning curve. 1 Among its disadvantages, in relation to TEP, are that it invades the abdominal cavity and that there is a higher percentage of hernias in the trocar orifices.

Evolution of TAPP and its implementationIn the early 1990s there was an increase in the number of publications describing the feasibility of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, although the technique had not been clearly defined, and some authors even described direct intraperitoneal placement of mesh. A few years later, a technique was described in which a U-shaped flap was used to place the preperitoneal mesh, which was later described as TAPP.4 Over the years, this technique has evolved into a reproducible and safe procedure that seeks to improve patient recovery by avoiding traumatic fixations while maintaining effectiveness.

One of the main initial problems that clearly limited the development of the laparoscopic approach to inguinal hernia was that its benefits were only evident when it was performed on bilateral and recurrent hernias, precisely those that required more surgical time and were the most complex to perform, which made it difficult to learn and implement. Cost was another major limiting problem, as was the need for all patients to undergo general anaesthesia.4 We are currently in a new era in which we are observing the progressive implementation of this technique in our hospitals. The new clinical guidelines, in which different scientific societies have been involved, have demonstrated the advantages of this approach even in unilateral primary hernias in men, offering a faster recovery for patients, who are able to return to their daily activities sooner. Furthermore, costs have drastically decreased due to the lower overall costs of laparoscopic material, and excellent results have been demonstrated without the use of traumatic fixation systems and using conventional flat polypropylene meshes. Finally, surgical times have decreased dramatically, as training courses have multiplied with a refined and standardised technique, and its use has also expanded to major outpatient surgery regimes.

The parallel evolution of anaesthetic techniques has meant that the need for general anaesthesia is no longer seen as a drawback of this technique. In fact, even international clinical guidelines1 advise against the use of locoregional anaesthesia in this type of procedure, as it is associated with increased urinary retention and an increase in medical complications in patients over 65 years of age.

Surgical technique step by step- 1

Anaesthesia, positioning, and preparation of the patient:

- •

It is not necessary to place a urethral catheter. There is currently no data to recommend its systematic use to decompress the bladder, and some groups only recommend the patient empty their bladder before going to the operating theatre.

- •

The patient is placed in the supine decubitus position with legs together, both arms close to the body, and the operating table placed slightly in Trendelenburg position. The monitor is placed at the patient's feet.

- •

The surgeon is positioned on the side contralateral to the hernia to be operated on. The assistant and the scrub nurse are positioned opposite the surgeon.

- •

The technique is performed under general anaesthesia with orotracheal intubation, as insufflation of the cavity prevents the use of local or locoregional anaesthesia.

- •

Finally, according to the EHS guidelines, the routine use of prophylactic antibiotherapy is not recommended.1

- •

- 2

Instruments required:

- •

30° scope, the calibre can be either 10 or 5 mm.

- •

One 10−11 mm and 2 5 mm trocars.

- •

Grasping forceps, dissector, scissors, and laparoscopic needle-holder.

- •

Mesh at least 12 × 15 cm, individualising the final size and pore size depending on the characteristics of each patient and the hernia.

- •

Fibrin glue, cyanoacrylates, or other traumatic fixation systems used, depending on the type of hernia and availability.

- •

Barbed suture for peritoneal closure.

- •

- 3

Creation of the pneumoperitoneum and placement of the trocars:

- •

In this case we must create the pneumoperitoneum following the usual technique of each working group, either with an open access, at umbilical level, or with the Veress needle, either at left hypochondrium or umbilical level: our group prefers the left hypochondrium.

- •

A 10 mm trocar is placed for the scope in the umbilical position and two 5 mm trocars, right and left para-umbilical, at the level of the clavicular midline.

- •

- 4

Dissection of the inguinal area. Once the scope has been introduced into the abdominal cavity, the anatomical landmarks that will be used to determine the dissection area are identified, which are basically the umbilical ligament, the epigastric vessels, the spermatic vessels, and the vas deferens, and their location with respect to the hernial defect, determining whether it is a medial or lateral inguinal hernial defect, or a femoral hernia. Once the anatomy has been identified, the following manoeuvres are performed:

- •

A grasping forceps is introduced through the left-hand trocar, while a scissor with electrocautery is introduced through the right-hand trocar.

- •

A horizontal incision is made in the parietal peritoneum about 2−3 cm above the deep inguinal ring, avoiding injury to the epigastric vessels. Its medial limit should be the umbilical ligament to avoid injury to the bladder, while the lateral limit should be that necessary for correct dissection and positioning of the mesh.

- •

Once the peritoneum has been opened, the anatomical landmarks of the area are identified, especially the pubis and Cooper's ligament, in the medial preperitoneal space of Retzius, and the triangle of pain, where the nerves of the area are located, in the lateral preperitoneal space of Bogros. Dissection of the peritoneum is continued to reduce the hernial sac, trying not to break the peritoneum, to maintain its integrity and to be able to close it correctly afterwards. This dissection differs according to the type of hernia.

- o

In medial hernias, the sac is reduced with traction and counter-traction, using two grasping forceps. Once dissected, the transversalis fascia is plicated to reduce the dead space and, as a consequence, the seroma. This manoeuvre is performed either with an endo-loop or with a tacker attached to the Cooper’s ligament, in our case we prefer the former option to reduce pain. The existence of a medial hernia does not preclude exploring whether there is a lateral component.

- o

In indirect hernias, traction and counter-traction movements are performed with two grasping forceps to progressively reduce the hernia sac, simultaneously identifying the elements of the cord, which must be prevented from traction to avoid injuring them. These elements will form an inverted V, where the internal branch is the vas deferens, and the lateral branch corresponds to the spermatic vessels. This area must be dissected until, when traction is applied to the peritoneum, the elements of the cord remain against the wall without coming with it, and medialisation of the proximal area of the vas deferens is clearly observed when correct dissection has been performed.

- o

In crural hernias the reduction manoeuvres are similar to those for medial hernias, but without performing the plication described above.

- o

- •

There are special circumstances to be considered during dissection of hernias of the inguinal region:

- o

Systematic exploration of the upper part of the deep inguinal ring is recommended to identify lipoma, regardless of whether a medial or lateral sac has been detected previously. If this manoeuvre is not performed, the patient may later report persistence of symptoms postoperatively and imaging tests may suggest recurrence.

- o

In inguino-scrotal hernias in which it is not possible to reduce the sac completely, it is sometimes necessary to divide the sac circularly, after identifying the cord elements to avoid injuring them, abandoning the distal end. This manoeuvre is controversial, as it may be related to the presence of a seroma in the postoperative period.

- o

In peritoneal-vaginal duct persistence, the peritoneum should be divided without complete reduction, as there is no sac with an end as such.

- o

- •

- 5

Once the dissection has been performed, the mesh is selected. The meshes used are usually polypropylene (approximately 12−15 cm) or, less frequently, PVDF or polyester, which should not be fenestrated to pass the cord, due to the increased risk of recurrence that this entails. These meshes can be preformed, which facilitates their positioning.

Regarding the type of mesh pore, there are no clear data demonstrating the advantages of large-pore, low-weight versus small-pore, high-weight meshes. There appears to be a trend towards large-pore meshes, as they may be associated with greater postoperative comfort.

The mesh is placed so that it completely covers the hernial defect and the entire posterior inguinal wall, including all areas where hernias occur in the area. The mesh should extend well beyond Cooper's ligament inferiorly (about 2 cm), allowing the cord elements to be parietalised.

- 6

Regarding mesh fixation, there is evidence that traumatic fixation can be avoided, although it has not been demonstrated that this can be done in large hernias (M3 and L3 according to the EHS classification, and especially in M3 hernias). If traumatic fixations are used, it is recommended that they be absorbable, and they should be placed avoiding dangerous triangle or “triangle of Doom”, an anatomical region bounded medially by the deferens, laterally by the spermatic vessels, and cranially by the apex of the triangle formed by these two structures in the internal inguinal ring, because important vascular structures run through this area. Furthermore, placement in the area known as the triangle of pain, lateral to the above triangle, where the nerve structures are located, should be avoided. Thus, fixation should only be performed at three points: the area of Cooper's ligament and pubis, the area of the posterior wall of the anterior rectus, and the lateral cranial area of this region.

Glues, such as cyanoacrylates5 and fibrin glues,6 can replace traumatic fixation, although has not been well defined whether it can be substituted in all cases, including cases with M3 hernias.7 There are groups that use fibrin glues and adhesives in all cases, regardless of the size of the defect, to avoid mesh displacement during awakening and in the early postoperative moments.

- 7

The peritoneal flap is then closed with a continuous suture; the new barbed sutures have made this manoeuvre easier, usually using a 3/0 resorbable suture of 15 cm in length. During this manoeuvre it is important to confirm that the peritoneum is closed correctly, avoiding the mesh being exposed to the intestinal loops, as this may cause adhesion at this level.

- 8

Finally, the abdominal cavity is checked, leaving no drainage, and closing the 10−11 mm umbilical trocar to avoid appearance of a hernia at this level.

The laparoscopic approach to inguinal hernia is not clearly uniquely indicated in cases where general anaesthesia is contraindicated or in large hernias, especially in those where there is loss of domicile, although, as previously mentioned, the most important thing is to individualise each case.

Whether to perform one or other laparoscopic surgical technique, TAPP or TEP, will depend on several factors, mainly the surgeon's preferences and the mastery of the technique in a given working group, as there are no clear advantages of one over the other.

Our group recommends mastery of both techniques, TEP being our first choice in our routine clinical practice for the treatment of inguinal hernia. However, there are cases in which TEP can be complex, and therefore we prefer to perform a TAPP, as it helps resolve the case. The cases in which we consider TAPP to be superior to TEP are as follows:

- 1

Cases in which there are doubts about correct access to the preperitoneal space, in which the attempt to access via TEP leads to rupture of the peritoneum:

- o

Previous infraumbilical preperitoneal surgery, such as prostatectomy.

- o

Suprapubic Pfannenstiel-type transverse incision.

- o

We can include women in these cases, where the peritoneum is intimately attached to the round ligament and TEP access may lead to its rupture. TEP is also a good option, although we have traditionally performed a TAPP.

- •

Recurrent hernias:

- •

- o

- o

Especially in those cases after an anterior approach with a previous mesh, especially when the repair was performed with placement of devices invading the anterior and posterior space, such as plugs or PHS (Prolene Hernia System) meshes.

- o

Recurrent hernias after a previous preperitoneal approach, although in these cases the anterior approach is recommended, but in cases of laparoscopic approach, TAPP is preferable to TEP.

- •

Cases where it is complex to manoeuvre in the limited preperitoneal space provided by the TEP:

- •

- o

Inguino-scrotal hernias, given the need to handle a sac of significant dimensions, which is complex in the reduced space created during TEP.

- o

Patients with significant obesity, since in these cases the lipomas that are usually detected in the inguinal ring can make it difficult to perform the TEP once they have been reduced.

- •

Hernias with content in the sac:

- •

- o

Irreducible hernias, because reduction of contents with a combined manoeuvre of traction from the inside and pressure from the outside is required.

- o

Hernias in emergency settings, as it facilitates the reduction of the contents and allows the viability of the intestine to be assessed. In addition, it allows evaluation of contamination, and deciding whether to continue with laparoscopic or open hernia repair.

- •

Opening of the peritoneum during TEP, as it is impossible to close the peritoneum using this approach route.

- •

Robotic surgery, as the limited space of the TEP makes it difficult to place the robotic arms.

- •

The first inguinal hernia repair using a robotic approach dates back to 2007, when Finley et al.8 reported a case of robotic prostatectomy combined with a mesh inguinal hernia repair. Since then, there has been growing interest in the use of robotic surgery to repair abdominal wall defects.

The robotic platform technology has great advantages, such as extended three-dimensional visualisation, stability, and joints with seven degrees of freedom, proved to facilitate the procedure for the surgeon and provide improved outcomes in complex cases. In this regard, in inguinal hernia repair, these improvements could be reflected in better visualisation of the inguinal anatomy and in facilitating dissections in complex cases, such as multi-recurrent hernias, offering greater ease and precision.

Despite these potential advantages, very few studies have been published comparing the laparoscopic and robotic approaches in the treatment of inguinal hernia. Most are characterised by small sample size, especially those on the robotic arm.9,10

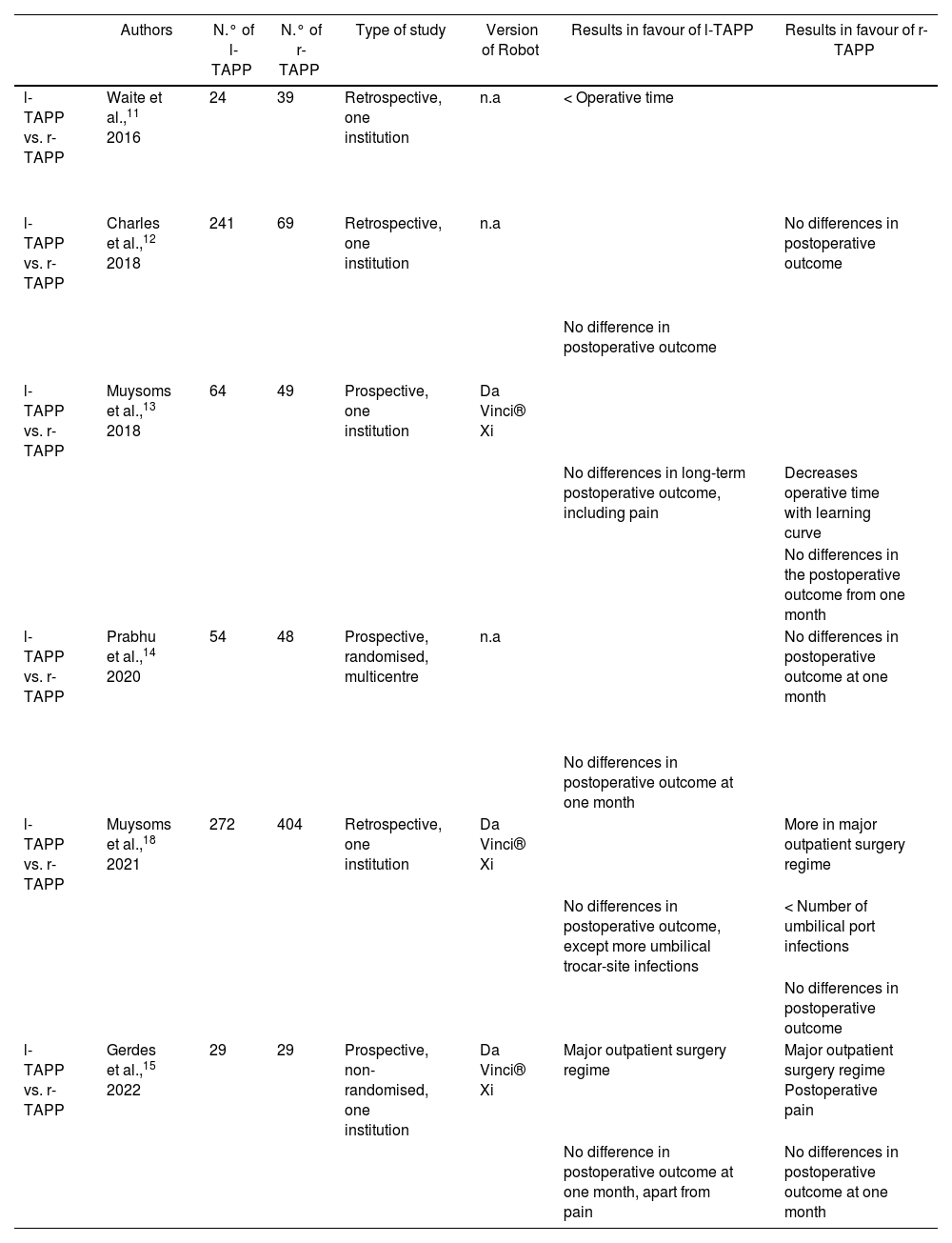

Of the studies that have been published in this regard, some compare the laparoscopic TEP approach with the r-TAPP approach, and it is interesting to note that almost all the robotic approaches are TAPP. In this analysis we have eliminated comparisons with TEP, as most studies include both laparoscopic techniques interchangeably versus r-TAPP, and therefore we include the few studies that compare l-TAPP with r-TAPP exclusively, the data is presented in Table 1.11,18

Comparative studies of laparoscopic TAPP versus robotic TAPP.

| Authors | N.° of l-TAPP | N.° of r-TAPP | Type of study | Version of Robot | Results in favour of l-TAPP | Results in favour of r-TAPP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-TAPP vs. r-TAPP | Waite et al.,11 2016 | 24 | 39 | Retrospective, one institution | n.a | < Operative time | |

| l-TAPP vs. r-TAPP | Charles et al.,12 2018 | 241 | 69 | Retrospective, one institution | n.a | No differences in postoperative outcome | |

| No difference in postoperative outcome | |||||||

| l-TAPP vs. r-TAPP | Muysoms et al.,13 2018 | 64 | 49 | Prospective, one institution | Da Vinci® Xi | ||

| No differences in long-term postoperative outcome, including pain | Decreases operative time with learning curve | ||||||

| No differences in the postoperative outcome from one month | |||||||

| l-TAPP vs. r-TAPP | Prabhu et al.,14 2020 | 54 | 48 | Prospective, randomised, multicentre | n.a | No differences in postoperative outcome at one month | |

| No differences in postoperative outcome at one month | |||||||

| l-TAPP vs. r-TAPP | Muysoms et al.,18 2021 | 272 | 404 | Retrospective, one institution | Da Vinci® Xi | More in major outpatient surgery regime | |

| No differences in postoperative outcome, except more umbilical trocar-site infections | < Number of umbilical port infections | ||||||

| No differences in postoperative outcome | |||||||

| l-TAPP vs. r-TAPP | Gerdes et al.,15 2022 | 29 | 29 | Prospective, non-randomised, one institution | Da Vinci® Xi | Major outpatient surgery regime | Major outpatient surgery regime Postoperative pain |

| No difference in postoperative outcome at one month, apart from pain | No differences in postoperative outcome at one month |

In 2021, Zhao et al.16 published a systematic review and meta-analysis including 8 studies with a total of 1379 patients. In their review they compared l-TAPP versus r-TAPP, reporting that no significant differences were found in postoperative pain or hospital stay, and no differences were found in complication rates. However, in this analysis, significant differences were found in operative time, which was longer in the r-TAPP group, and the costs of the interventions were also analysed. In conclusion, no differences were found in terms of clinical outcomes and safety between the two approaches.

A subsequent systematic review and meta-analysis published in October 2022 by Solaini et al.17 included 9 studies with a total of 64,426 patients. This analysis concludes that laparoscopic and robotic inguinal hernia repair have similar safety parameters and postoperative outcomes. The robotic approach may require longer operative time if a unilateral repair is performed (160 versus 90 min); however, in the bilateral approach the operative time was similar (111 versus 100 min). A differentiating aspect between the two approaches is that costs are higher in the robotic approach group, with a mean of $3270 ($4757 versus $1782), which would suggest that further studies focusing solely on bilateral repair could help to highlight the advantages of using the robotic platform.

In line with data showing that the robotic approach is more expensive than the conventional laparoscopic approach for inguinal hernia repair, the EASTER study, published by Muysoms et al.18 and including 676 patients (202 l-TAPP and 404 r-TAPP patients), shows that r-TAPP was significantly more expensive than conventional laparoscopy, at a mean of euro2612 versus euro1,963. In this study, the robotic group treated more patients on an outpatient basis, and postoperative complications were infrequent and mild.

In this regard, Higgins et al.19 published a study in which they concluded that they observed a significant increase in the cost of general surgical procedures to the health system when cases that are usually performed laparoscopically are performed robotically. The analysis is limited in that only costs associated with surgical consumables were included. The initial acquisition cost, depreciation, and maintenance contract for robotic and laparoscopic systems were not included in this analysis.

Therefore, we can state that robotic inguinal hernia repair involves an increase in the cost of the procedure; it is a safe approach with outcomes similar to those of the laparoscopic approach. Its value remains to be determined in complex multi-recurrent hernias, after prostatectomy or inguino-scrotal hernias, which pose a challenge for the conventional laparoscopic approach.20 However, robotic repair of inguinal hernias may be a way to decrease the learning curve for abdominal wall surgeons before tackling complex ventral hernias via this route, facilitating the development of the skills needed to dissect and suture in more complex cases. It may even do what cholecystectomy did for the laparoscopic approach, providing a start for the development of complex cases in other areas of specialisation, of course after a process of learning the anatomy and with the supervision of an abdominal wall expert.

The future of the laparoscopic TAPP approachThe laparoscopic approach to inguinal hernia undoubtedly has a great future as the gold standard procedure in the management of inguinal hernia, given its advantages over the open approach, due to the progressive implementation of this technique, or the standardisation of the procedure, and the clear reduction in costs compared to the early days of the technique.

The prevalence of inguinal hernia means that its minimally invasive repair must be mastered by most general surgeons, because most centres are a long way from acquiring a robotic platform, which, if there is one will be used for other types of procedures or for more complex hernias, as mentioned above.

However, one of the fundamental aspects of the future of inguinal hernia repair is not the implementation of the laparoscopic approach for all cases. The future is determined by the importance of determining which type of hernia21 and which type of patient22 will benefit most from repair using one type of approach or another, i.e., whether they are candidates for an open, laparoscopic, or robotic approach. In this respect, registries and artificial intelligence will be able to help us determine these aspects.

These artificial intelligence mechanisms may also be useful for performing a safer TAPP, identifying key manoeuvres and determining anatomical references to help us guide the surgery while a minimally invasive approach is being performed, which will undoubtedly help to reduce morbidity, avoid chronic pain and recurrence, and facilitate learning this surgery.23

With regard to the material, new generations of meshes and fixation mechanisms will favour surgery with early recovery without long-term complications, and artificial intelligence will also help us not only to select the best approach, but also to choose the type of mesh and fixation required by each patient individually, thus promoting personalised surgery.

Contributions of the authorsAll the authors participated in the study design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of results, preparation of the manuscript, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Morales-Conde S, Balla A, Navarro-Morales L, Moreno-Suero F, Licardie E. ¿Es preferible el TAPP por vía laparoscópica para el tratamiento de la hernia inguinal? Técnica, indicaciones y expectativas de futuro. Cir Esp. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2023.01.003