The study of the health related quality of life in patients with digestive tract cancer, and particularly in those with tumours of the oesophagus and stomach, provides useful information for selecting the most suitable therapeutic option. It may also be used to predict the impact of the disease and its possible treatments on the physical, emotional and social condition of the patient.

Various sensitive and reliable tools have been developed over the past decades that are capable of measuring the quality of life of patients; the use of questionnaires has made it easier to exchange information between the patient and the doctor. The pre- and post-operative variations in the quality of life in patients with oesophageal–gastric cancer are of prognostic value on the outcome of the disease.

For all these reasons, the health related quality of life is currently considered, along with disease free survival and absence of recurrences, one of the most important parameters in order to assess the impact on the patients of a particular oncological treatment.

The aim of this article is to review the role of the health related quality of life assessment, as well as the various tools which are available to measure it in patients with oesophageal–gastric cancer.

El estudio de la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en pacientes con cáncer digestivo y, de modo especial, en aquellos con tumores del esófago y del estómago, proporciona una información útil para seleccionar la opción terapéutica más adecuada y, asimismo, predecir el impacto de la enfermedad y, de sus posibles tratamientos, sobre la condición física, emocional y social del paciente.

En las últimas décadas se han desarrollado y validado diversos instrumentos que miden la calidad de vida de los pacientes de forma sensible y fiable; la utilización de cuestionarios ha facilitado el intercambio de esta valiosa información entre el paciente y el médico. Las variaciones pre y postoperatorias de la calidad de vida en pacientes con cáncer esófago-gástrico poseen valor pronóstico sobre la evolución de la enfermedad.

Por todas estas razones, la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud se considera hoy en día, junto con la supervivencia libre de enfermedad y la ausencia de recidivas, uno de los parámetros más importantes para poder evaluar el impacto de un determinado tratamiento oncológico sobre los pacientes.

El propósito de este artículo es revisar el papel de la valoración de la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud, así como los diversos instrumentos de los que se dispone para medirla, en los pacientes con cáncer esófago-gástrico.

Ever since 1948, health was defined as “...a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing, not merely the absence of disease”,1 the study of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) has experienced an exponential growth.2 This is especially so in cancer patients, such as those with gastro-oesophageal cancers, whose treatment can cause undesirable side effects in pursuit of what is sometimes a very limited increase in survival.3–5

It is very important for the surgeon who treats these patients to clearly let them know the effects of treatment on survival and, in particular, on their quality of life. The patient must participate in decision-making and be aware of the impact of treatment on the quality of daily life.6 In patients eligible for the curative or palliative treatment of oesophageal and gastric cancers, the prognostic value of some baseline HRQoL parameters and their changes over time is important.4,6–10 Given the importance of assessing the quality of life through well-designed studies using highly sensitive and validated instruments,3,4 it is important for the doctor to be able to communicate this to the patient in an understandable way.6,11,12

Our goal is to define HRQoL and analyse instruments used for its evaluation, with special attention to patients with oesophageal and gastric cancer.

Definition of HRQoLThe term HRQoL refers to a multidimensional construction that measures patients’ perception of the positive and negative aspects associated with their disease and its treatment, in at least 4 aspects: physical, emotional, psychological, and treatment-related.2,4,13,14

A concise definition proposed by Schipper et al.15 is “the functional consequences of disease and its treatment as perceived by the patient.”

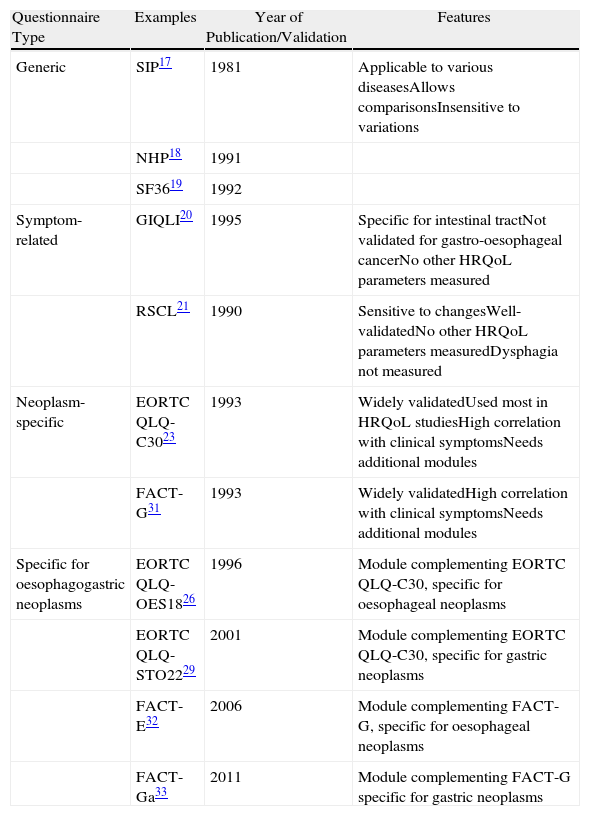

Instruments for Measuring HRQoLCurrently the instruments most frequently used to measure HRQoL are self-administered questionnaires,4 as patients themselves are the most appropriate source of information about their own HRQoL4,6,16 (Table 1).

Questionnaires Used for the Study of HRQoL in Patients Suffering From Oesophageal–Gastric Cancer.

| Questionnaire Type | Examples | Year of Publication/Validation | Features |

| Generic | SIP17 | 1981 | Applicable to various diseasesAllows comparisonsInsensitive to variations |

| NHP18 | 1991 | ||

| SF3619 | 1992 | ||

| Symptom-related | GIQLI20 | 1995 | Specific for intestinal tractNot validated for gastro-oesophageal cancerNo other HRQoL parameters measured |

| RSCL21 | 1990 | Sensitive to changesWell-validatedNo other HRQoL parameters measuredDysphagia not measured | |

| Neoplasm-specific | EORTC QLQ-C3023 | 1993 | Widely validatedUsed most in HRQoL studiesHigh correlation with clinical symptomsNeeds additional modules |

| FACT-G31 | 1993 | Widely validatedHigh correlation with clinical symptomsNeeds additional modules | |

| Specific for oesophagogastric neoplasms | EORTC QLQ-OES1826 | 1996 | Module complementing EORTC QLQ-C30, specific for oesophageal neoplasms |

| EORTC QLQ-STO2229 | 2001 | Module complementing EORTC QLQ-C30, specific for gastric neoplasms | |

| FACT-E32 | 2006 | Module complementing FACT-G, specific for oesophageal neoplasms | |

| FACT-Ga33 | 2011 | Module complementing FACT-G specific for gastric neoplasms |

EORTC QLQ, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire; FACT, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; GIQLI, Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index; NHP, Nottingham Health Profile; RSCL, Rotterdam Symptom Checklist; SF-36, Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SIP, Sickness Impact Profile.

These instruments must meet 3 methodological parameters: reliability, validity and responsiveness2,13 and are divided into generic, symptom-related, and cancer-specific (supplemented by specific modules for each type of neoplasia).4,13

Generic InstrumentsThese are based on scales used in a group of population affected by different types of diseases.4 Examples are the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP),17 the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP)18 and the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF36).19 They allow comparison of HRQoL among patients affected by different diseases, but are insensitive to individual variations in HRQoL parameters.4

Symptom-related InstrumentsThese are based on measuring symptoms perceived by the patient, regardless of other HRQoL parameters.13 The Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) is a questionnaire consisting of 36 items, specifically designed to measure symptoms associated with diseases of the digestive tract.20 The Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (RSCL) is a questionnaire based on 38 items and a generic question about the HRQoL status,21 which was later modified to include a dysphagia scale in patients with oesophageal neoplasia.22

Cancer-specific InstrumentsCurrently, the most used are the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ) C30 and the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G).

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a self-administered questionnaire, specific for patients with cancer, which measures 5 functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social), 3 symptom scales (fatigue, pain, nausea/vomiting) and a scale for overall HRQL status, to which are added 5 unique questions on specific symptoms (dyspnoea, loss of appetite, sleep disturbances, constipation and diarrhoea).23 All parameters analysed are measured on a scale between 0 and 100 whose variation between 5 and 10 points is considered clinically significant.4,24 This general cancer questionnaire has been supplemented by specific modules for each type of cancer, thus maintaining an acceptable level of generality, which is useful for comparing different studies, as well as adding high sensitivity to detect small but clinically important variations in patient HRQoL.4,13,25

The specific EORTC module for oesophageal cancer (EORTC QLQ-OES18) was developed in 199626 and later validated in a multicentre study of 491 patients.27 A specific module for gastric cancer (EORTC QLQ-STO22)28,29 was prepared and clinically validated in the same way. Recently, a new module (EORTC QLQ-OG25) was validated which combines the domains measured in the modules OES18 and STO22 for patients suffering from gastric, oesophageal or oesophagogastric junction neoplasia.30

FACT-G is a questionnaire consisting of 27 questions on HRQoL with 4 domains (physical, social/family, emotional and functional).31 Similarly, and with the same objectives as the questionnaires QLQ-STO22 and QLQ-OES18, specific modules for gastric and oesophageal cancer associated with the FACT-G questionnaire (FATC-Ga and FACT-E) were prepared and validated.32,33

Measuring HRQoL in Patients With Oesophageal CancerThe impact of oesophagectomy on HRQoL in patients has been studied in the last decade through prospective studies using widely validated measurement instruments.4,5,34

Most HRQoL aspects, both functional scales and symptoms, are significantly impaired during the first few months after surgery, regardless of the surgical technique used,4,5,34–38 except for the emotional component which improves in the immediate postoperative period,4,5,34,35,38 due probably to relief perceived by the patient after the operation.4

After the initial postoperative deterioration in HRQoL, some parameters gradually improve, recovering preoperative levels,4,34 while others, such as dyspnoea, reflux or diarrhoea, never return to pre-surgery values.34 One exception is dysphagia, which has been shown to be stable or to improve after surgery.4,5,35

When comparing the HRQoL of patients after oesophageal cancer surgery with the general population, there is an overall deterioration of almost all HRQoL parameters 6 months after surgery, which only recover partially in those who survive at 3 years.36 A prospective study by Lagergren et al.34, of 47 patients with a minimum survival of 3 years, showed a deterioration in most HRQoL parameters during the immediate postoperative period. These recovered in the long-term, with the exception of respiratory function, reflux and diarrhoea which maintained their tendency to deterioration. Other studies confirm the persistence of symptoms such as reflux and pain in patients with prolonged survival.4

For patients with a tumour located in the oesophogastric junction, a total gastrectomy provides better HRQoL than transthoracic oesophagectomy 6 months after the operation. This could therefore be considered an advisable procedure for this subgroup of patients.39Other factors, such as anastomotic dehiscence, infections, cardiovascular complications or other complications related to surgical technique, as well as the presence of other diseases before surgery, advanced tumour stages (III and IV) and tumour location in the upper third of the oesophagus, are predictors of a worse postoperative HRQoL.40–42

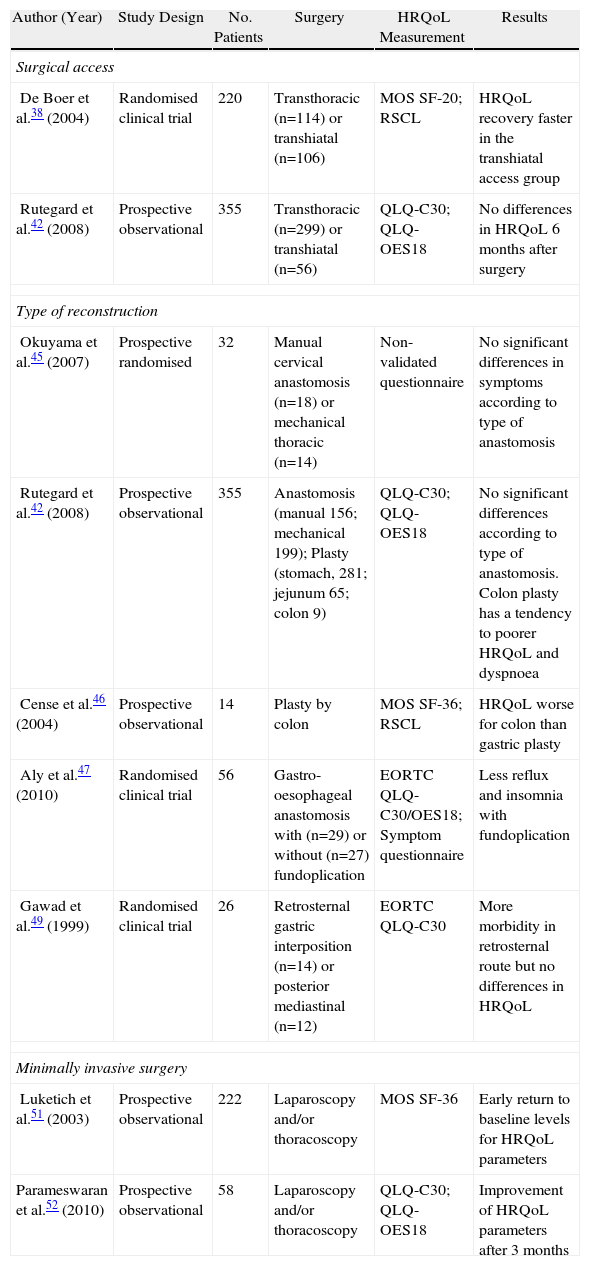

Factors related to surgical technique, such as access, the type of reconstruction or the use of minimally invasive surgery can have an impact on HRQoL and deserve special attention (Table 2).

Examples of Studies Measuring the Impact of Oesophageal Surgery on HRQoL.

| Author (Year) | Study Design | No. Patients | Surgery | HRQoL Measurement | Results |

| Surgical access | |||||

| De Boer et al.38 (2004) | Randomised clinical trial | 220 | Transthoracic (n=114) or transhiatal (n=106) | MOS SF-20; RSCL | HRQoL recovery faster in the transhiatal access group |

| Rutegard et al.42 (2008) | Prospective observational | 355 | Transthoracic (n=299) or transhiatal (n=56) | QLQ-C30; QLQ-OES18 | No differences in HRQoL 6 months after surgery |

| Type of reconstruction | |||||

| Okuyama et al.45 (2007) | Prospective randomised | 32 | Manual cervical anastomosis (n=18) or mechanical thoracic (n=14) | Non-validated questionnaire | No significant differences in symptoms according to type of anastomosis |

| Rutegard et al.42 (2008) | Prospective observational | 355 | Anastomosis (manual 156; mechanical 199); Plasty (stomach, 281; jejunum 65; colon 9) | QLQ-C30; QLQ-OES18 | No significant differences according to type of anastomosis. Colon plasty has a tendency to poorer HRQoL and dyspnoea |

| Cense et al.46 (2004) | Prospective observational | 14 | Plasty by colon | MOS SF-36; RSCL | HRQoL worse for colon than gastric plasty |

| Aly et al.47 (2010) | Randomised clinical trial | 56 | Gastro-oesophageal anastomosis with (n=29) or without (n=27) fundoplication | EORTC QLQ-C30/OES18; Symptom questionnaire | Less reflux and insomnia with fundoplication |

| Gawad et al.49 (1999) | Randomised clinical trial | 26 | Retrosternal gastric interposition (n=14) or posterior mediastinal (n=12) | EORTC QLQ-C30 | More morbidity in retrosternal route but no differences in HRQoL |

| Minimally invasive surgery | |||||

| Luketich et al.51 (2003) | Prospective observational | 222 | Laparoscopy and/or thoracoscopy | MOS SF-36 | Early return to baseline levels for HRQoL parameters |

| Parameswaran et al.52 (2010) | Prospective observational | 58 | Laparoscopy and/or thoracoscopy | QLQ-C30; QLQ-OES18 | Improvement of HRQoL parameters after 3 months |

EORTC QLQ, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire; MOF SF-20/36, medical outcomes study short form 20/36; RSCL, Rotterdam Symptom Checklist.

Only 1 randomised clinical trial has evaluated the effect of surgical access on postoperative HRQoL in patients, using previously validated instruments.38,43 For patients with a transthoracic access, there was an increase of symptoms related to surgery and a decreased level of activity during the first postoperative year when compared with a group of patients with the transhiatal access,38 with no clear increase in survival.43 Recently, Rutegard et al.42 found no significant differences in HRQoL values for different types of surgical access in a cross-sectional study of 355 patients, 6 months after completion of the oesophagectomy.

Type of ReconstructionThe type of anastomosis and type of reconstruction used to restore the continuity of the digestive tract and its location in the chest or neck region may have significant impact on HRQoL.

In a cross-sectional study of 46 patients, Schmidt et al.44 observed a deterioration in patients who had undergone an intrathoracic anastomosis compared with patients who had undergone cervical anastomosis, especially in reflux and insomnia related to it. Okuyama et al.45 found no significant differences in postoperative symptoms when comparing manual cervical and mechanical intrathoracic anastomoses in a prospective randomised trial of 32 patients using a non-validated questionnaire.

Rutegard et al.42 found no significant differences in the HRQoL parameters measured by EORTC QLQ-C30 and OES18, according to the anastomosis technique used (manual or mechanical) or the type of reconstruction (stomach, colon or jejunum).

Cense et al.46 found an overall deterioration in HRQoL, and an increase in specific symptoms, 21 months after performing a colonic interposition reconstruction, when compared with gastric interposition.

When compared with patients who had a traditional oesophagogastric anastomosis, a recent prospective randomised study on 56 patients by Aly et al.47 observed a significant reduction in postoperative symptoms, especially of reflux and heartburn, in patients who underwent an oesophagogastric anastomosis associated with fundoplication as an antireflux technique.

Finally, 2 studies examined HRQoL in patients according to the placement of angioplasty and anastomosis. Nakajima et al.48 compared upper thoracic anastomosis in the posterior mediastinum with cervical anastomosis with interposition via the retrosternal posterior mediastinal route, and concluded that the former had less impact on postoperative HRQoL. In a prospective randomised study, Gawad et al.49 compared gastric reconstruction via the posterior mediastinal route with retrosternal and observed no changes in HRQoL, despite a higher rate of morbidity and mortality in the retrosternal group.

Minimally Invasive SurgeryThe study of the impact of this type of surgical technique on HRQoL has experienced rapid growth, particularly in the last five years.50–53

In a large series of cases, Luketich et al.51 showed an early recovery from most HRQoL parameters to baseline levels during the postoperative period of minimally invasive oesophagectomy, although the patient follow-up was not performed by specific instruments for oesophageal neoplasia.4 Parameswaran et al.52 observed a near-global deterioration of HRQoL 6 weeks after the same operating technique, with an early recovery between 3 and 6 months postoperatively, which remained in the control carried out after a year.

Palliative Treatment of Oesophageal CancerRecently, many studies have included the measurement of HRQoL among parameters to be considered when choosing between different palliative treatments for oesophageal cancer, although not always performed by validated methods.6,54–56

Some examples of prospective randomised studies using sensitive instruments to measure HRQoL are: the study by Homs et al.57, which compared self-expanding metal stents with single dose brachytherapy; the study by Shenfine et al.58, which compared self-expanding prosthesis with other endoscopic and non-endoscopic treatments; and that of Dallal et al.56, which evaluated HRQoL after palliative treatment with thermal ablation or self-expanding prosthesis. Currently, self-expanding prosthesis, brachytherapy and thermal ablation techniques are the commonly used palliative techniques to treat malignant oesophageal strictures, because they achieve improved palliation of dysphagia, better HRQoL and a lower rate of complications when compared with other palliation methods, such as surgery, chemotherapy or rigid prosthesis.54–57 A self-expanding prosthesis achieves faster relief of symptoms when compared with endoluminal brachytherapy. The latter however has sustained improvement in HRQoL time, so it is advisable in patients with expected prolonged survival (3–6 months).54,55,57 Thermal ablation achieves palliation of symptoms and improvement in HRQoL comparable with the two previous techniques, but needs a greater number of repeat procedures to do so.54–56

Measuring HRQoL in Patients With Gastric CancerDespite the recognized importance of studying HRQoL in patients affected by gastric cancer, only 11 from a recent systematic review of 87 randomised studies, of surgical technique in the treatment of this condition, included some method of measuring HRQoL, and only 7 used a specific instrument.3

In general, patients with gastric cancer reported a greater number of preoperative symptoms such as insomnia, decreased sexual activity and loss of appetite, compared with the general population.59

After curative surgical treatment with total gastrectomy (TG) or subtotal gastrectomy (STG), patients show an initial deterioration in most functional scales, which gradually recovers between 3 and 6 months after being operated.60–62 However, emotional and social scales show no change or early improvement, as seen in patients after an oesophagectomy.4,5,34,35,38 This overall gradual improvement was not seen so clearly in gastrointestinal symptoms, such as dietary restrictions, loss of appetite and diarrhoea, which were still high 6 months60 to a year62 after surgery.

A cross-sectional study by Tyrvainen et al.63, in patients with a minimum survival of 5 years after TG, observed they differed from the general population only in sleep disturbances, stress and voiding function disturbances. Some non-surgical factors that seem to influence postoperative HRQoL parameters are pre- and post-operative weight loss,64,65 recurrent disease,4 the number of associated diseases,61 smoking habit,61 female sex61 and lower level of education.61

The effect of some factors related to the surgical technique on HRQoL deserves a more detailed review.

Type of Oesophageal CancerThe extent of lymphadenectomy performed does not appear to influence postoperative HRQoL, according to the literature reviewed.66,67 These results were confirmed in a randomised study on 214 patients who underwent D1 or D3 lymphadenectomy, which used the Spitzer Index questionnaire and an ad hoc questionnaire to measure HRQoL.68

Type of ResectionA single randomised study compared post-operative HRQoL in patients after SG and STG.69 Although no specific or self-administered instruments were used to measure HRQoL, the study findings agree with other studies, noting a better overall HRQoL in patients after undergoing STG.4,62,69–73

After TG, patients have a greater deterioration in physical function,4,62 need a greater number of daily meals,72 make a greater number of stools,72 lose more weight,72 as well as suffer increased nausea, loss of appetite62,73 and dietary restrictions.62

Whenever possible, and maintaining appropriate resection margins, STG provides better postoperative HRQoL and is the treatment of choice for distal stomach tumours.4,62,69–73 A randomised study is needed to compare both techniques using validated instruments to measure HRQoL.

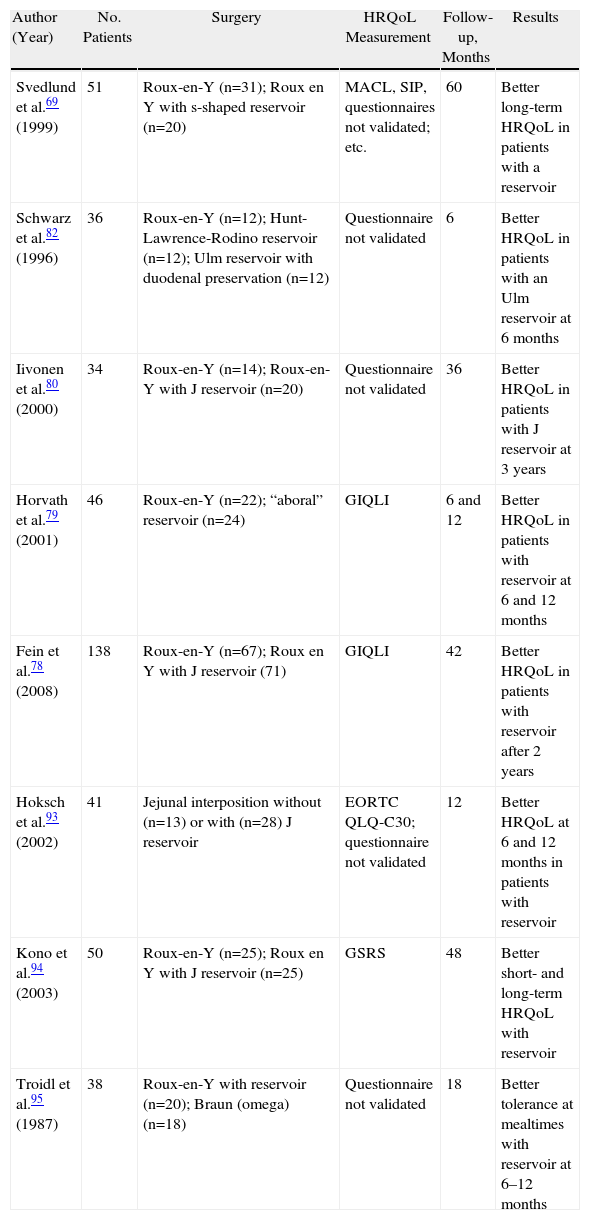

Type of ReconstructionThe type of reconstruction to be used after total gastrectomy, the need for the preservation of the duodenal passage, the importance of a reservoir and its size are of great controversy in the surgical literature and are the technical aspects most studied in relation to HRQoL4,74–78 (Table 3). A review of these studies, performed by different and non-validated instruments, could draw no clinically relevant conclusions from them.A recent meta-analysis of 21 randomised studies, evaluating the influence of performing a jejunal reservoir in the reconstruction of the transit after gastrectomy, showed that the most did not measure the HRQoL of patients or did so with non-validated questionnaires.77 Two studies that reported on postoperative HRQoL from the GIQLI questionnaire agreed that patients reconstructed with a reservoir had better HRQoL after 2 years postoperatively.78,79 Reconstruction via jejunal reservoir seems also to allow higher volume and less fractionated food.80,81 Therefore, performing a reservoir is justified in patients with expected long-term survival.77–79

Randomised Prospective Studies Evaluating Post-operative HRQoL in Patients Who Underwent Gastrectomy With or Without Reconstruction Using Reservoir.

| Author (Year) | No. Patients | Surgery | HRQoL Measurement | Follow-up, Months | Results |

| Svedlund et al.69 (1999) | 51 | Roux-en-Y (n=31); Roux en Y with s-shaped reservoir (n=20) | MACL, SIP, questionnaires not validated; etc. | 60 | Better long-term HRQoL in patients with a reservoir |

| Schwarz et al.82 (1996) | 36 | Roux-en-Y (n=12); Hunt-Lawrence-Rodino reservoir (n=12); Ulm reservoir with duodenal preservation (n=12) | Questionnaire not validated | 6 | Better HRQoL in patients with an Ulm reservoir at 6 months |

| Iivonen et al.80 (2000) | 34 | Roux-en-Y (n=14); Roux-en-Y with J reservoir (n=20) | Questionnaire not validated | 36 | Better HRQoL in patients with J reservoir at 3 years |

| Horvath et al.79 (2001) | 46 | Roux-en-Y (n=22); “aboral” reservoir (n=24) | GIQLI | 6 and 12 | Better HRQoL in patients with reservoir at 6 and 12 months |

| Fein et al.78 (2008) | 138 | Roux-en-Y (n=67); Roux en Y with J reservoir (71) | GIQLI | 42 | Better HRQoL in patients with reservoir after 2 years |

| Hoksch et al.93 (2002) | 41 | Jejunal interposition without (n=13) or with (n=28) J reservoir | EORTC QLQ-C30; questionnaire not validated | 12 | Better HRQoL at 6 and 12 months in patients with reservoir |

| Kono et al.94 (2003) | 50 | Roux-en-Y (n=25); Roux en Y with J reservoir (n=25) | GSRS | 48 | Better short- and long-term HRQoL with reservoir |

| Troidl et al.95 (1987) | 38 | Roux-en-Y with reservoir (n=20); Braun (omega) (n=18) | Questionnaire not validated | 18 | Better tolerance at mealtimes with reservoir at 6–12 months |

GIQLI, Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index; GSRS, Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Score; MACL, Mood Adjective Check List; SIP, Sickness Impact Profile.

Some authors advocate the preservation of the duodenal transit because it seems to be associated with better HRQoL, less weight loss and better hormonal regulation of intestinal motility 6 months after surgery.82 These results have not been confirmed by long-term follow-up studies.83

Conclusions drawn from each study separately are rare, although they all seem to favour the implementation of a reservoir in patients with longer life expectancy.77,78,81 Further studies are needed to implement sensitive instruments to measure HRQoL, allowing a better comparison of results.

Minimally Invasive SurgeryRecently, Kim et al.84 published a randomised study comparing HRQoL during the first 3 months postoperatively in patients after subtotal, laparoscopic and open gastrectomy, using EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22. The minimally invasive group had significantly better results in the role, physical, social and emotional scales as well as a score reduction in 10 symptom scales.

Other non-randomised studies confirm the initial advantage of laparoscopic surgery for HRQoL parameters, and the gradual reduction of differences between the two techniques over time.62

Palliative Treatment of Gastric CancerDespite the importance of studying HRQoL in patients with gastric cancer subjected to palliative treatment being now universally accepted,4,6 surprisingly, a recent systematic review of palliative chemotherapy of gastric neoplasia by Wagner et al.85 noted the lack of measurement of HRQoL parameters in most of the studies included.

Chemotherapy has been shown to not only increase survival but also to improve HRQoL when compared with therapeutic abstention (best supportive care).4,6,85 Although combination chemotherapy has demonstrated improved survival when compared with chemotherapy with a single drug,85 the first option also has increased treatment-related toxicity without a clear improvement in HRQoL.85,86

The association of 5-FU with irinotecan has demonstrated minimal improvement in HRQoL when compared with the combination of 5-FU with cisplatin,6,87,88 as well as triple therapy containing docetaxel.6,89

Studies comparing the use of self-expanding metal stents with the performance of surgical gastro-jejunostomy for palliation of mechanical obstruction caused by distal gastric cancer seem to favour endoscopic therapy in patients with reduced life expectancy (<2 months) and surgery in patients with more prolonged expected survival.90–92 These results were confirmed by a recent randomised study.91

ConclusionsHRQoL is today one of the main parameters to be evaluated in studies of oesophagogastric cancer surgery results. The creation of specific HRQoL measurement instruments means the variation in health perceived by our patients can be studied sensitively and accurately, and these results from our clinical practice can be compared with other groups in the world. This measurement takes on paramount importance in patients with reduced life expectancy, and those to be subjected to aggressive surgical treatment. The variation in HRQoL occurring after a certain treatment is something the surgeon should be aware of when informing the patient of several therapeutic options. Recent studies show the prognostic value of changes in HRQoL parameters, supporting the practical importance of its knowledge and measurement for both patient and surgeon.

Finally, prospective studies are required which include the measurement of HRQoL at baseline and after treatment, using validated instruments, such as the EORTC QLQ or the FACT-G, in all areas of the oesophagus-gastric cancer surgery.

Please cite this article as: Dorcaratto D, et al. Calidad de vida en pacientes con cáncer de esófago y de estómago. Cir Esp. 2011;89:635–44.