SI: Minimally invasive surgery of the abdominal wall

Más datosAbdominal wall hernias are common entities that represent important issues. Retromuscular repair and component separation for complex abdominal wall defects are considered useful treatments according to both short and long-term outcomes. However, failure of surgical techniques may occur. The aim of this study is to analyze results of surgical treatment for hernia recurrence after prior retromuscular or posterior components separation. We have retrospectively reviewed patient charts from a prospectively maintained database. This study was conducted in three different hospitals of the Madrid region with surgical units dedicated to abdominal wall reconstruction. We have included in the database 520 patients between December 2014 and December 2021. Fifty-one patients complied with the criteria to be included in this study. We should consider offering surgical treatment for hernia recurrence after retromuscular repair or posterior components separation. However, the results might be associated to increased peri-operative complications.

Las hernias de la pared abdominal constituyen una patología con importantes repercusiones. La reparación retromuscular, así como la separación de componentes para el tratamiento de las hernias complejas de la pared abdominal, son tratamientos efectivos con buenos resultados tanto a corto como a largo plazo. Sin embargo, pueden surgir recurrencias herniarias. El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar los resultados del tratamiento quirúrgico de las recurrencias herniarias tras una reparación retromuscular o separación posterior de componentes previas. Hemos analizado retrospectivamente las historias clínicas de 520 pacientes tratados en tres hospitales de la Comunidad de Madrid con unidades clínicas dedicadas a la reconstrucción de la pared abdominal. Hemos incluido a 520 pacientes entre diciembre 2014 y diciembre 2021. Cincuenta y un pacientes cumplían los criterios para ser incluidos en el estudio. El tratamiento de las recidivas tras los procedimientos señalados debe considerarse, entendiendo que se asocian a más complicaciones perioperatorias.

Hernia recurrence has a great impact on quality of life. Its treatment is important due to several expected complications and economic consequences. In the Spanish environment, 22.2% of all operated hernias were recurrences. Specifically, 36.4% and 16.3% of all patients with abdominal wall hernias received retromuscular/preperitoneal (RM) mesh repair and component separation (CS) respectively.1 In a recent study, 10% hernia recurrence after CS was reported (15 months median follow-up).2 Despite improvement of surgical techniques, the magnitude of patients that are at risk of hernia recurrence after these procedures seems to be significant.3 The first step of both anterior and posterior CS is the Rives procedure that consists of the medial detachment of posterior rectus sheath to access the RM space. Anterior CS adds the release of the external oblique muscle. Mesh reinforcement is placed in the retrorectus space4 or as an onlay reinforcement.5,6 Posterior CS releases laterally the posterior rectus sheath to access the preperitoneal/pre-fascia transversalis planes.7 Then, a RM preperitoneal plane is enlarged to obtain a landing zone to place a large mesh.

Hernia recurrence after CS or RM may happen and lays out a challenging issue.3 Depending on the origin of the recurrence, different strategies might be considered. Recurrences may happen due to infection, mesh disruption or insufficient overlap. They can also be attributed to pitfalls of the technique itself.8 Patients with hernia recurrence and indication for reoperation after RM or CS repair should be offered surgical treatment with the best opportunities in terms of short and long-term outcomes. The aim of this study is to analyze our surgical approach to treat hernia recurrences after a previous RM or posterior CS repair.

Material and methodsWe have retrospectively reviewed patient charts from a prospectively maintained database. This study was conducted in three different hospitals of the Madrid region with surgical units dedicated to abdominal wall reconstruction. These hospitals are homogeneous in terms of surgical indications, procedures and follow-up. Between December 2014 and December 2021, we have included in the database 520 patients. All patients met the criteria for complex abdominal wall defects according to Slater.9 We defined RM repair as the procedure that only involved the retrorectal3 or RM preperitoneal planes. We considered posterior CS whenever we performed a lateral release on the posterior rectus sheath. We have followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) recommendations for observational studies,10 and the international classification of abdominal wall planes (ICAP).11 Prior to conducting this study, a protocol was approved by Local Ethics Committee (ID: 39/2019). Patients provided informed consent to be included in prospective studies prior to surgery. We obtained Institutional Review Board approval.

In our unit, we scheduled all patients with complex abdominal wall defects for an optimization program as described elsewhere.12 We consider that preoperative CT scan is mandatory, especially in “redo” surgeries. In axial and sagittal views, we always evaluate the size and number of defects, muscle atrophy, abdominal and hernia volumes, in order to plan the surgical strategy. We also assessed previous incisions when planning reoperations to avoid as much as possible wound morbidity.

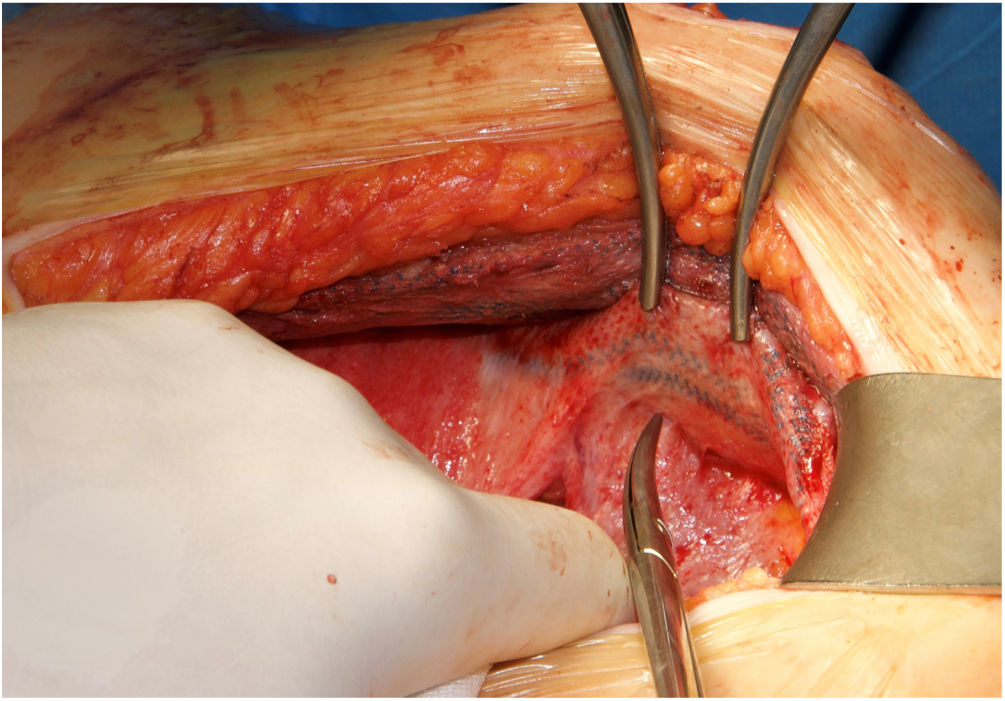

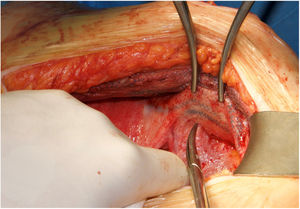

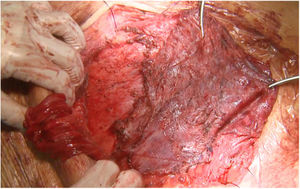

Surgical techniqueIn cases of midline recurrences, our initial plan is to perform a new RM access bilaterally. We do not remove the sac until we consider that it is not necessary to complete the repair. Previous implanted RM meshes are usually stuck to the peritoneum and remnants of posterior rectus sheath. We always try to dissect the space between the fibrosis of the mesh and the rectus muscle, leaving the previous mesh over the peritoneum. We advise trying to work from a non-touched area to the area where there is a previous mesh in order to better identify the layers. Our policy is trying to preserve previous meshes if they are well integrated. They can be used later to close both posterior and anterior layers. If the dissected space was wide enough to provide sufficient mesh overlap of the defect and to close both the posterior and anterior layers of the abdominal wall, the Rives procedure was completed with a new RM mesh. Whenever we considered the overlap inadequate or that the abdominal layers could not be closed without tension, we performed a posterior CS. In this situation, we advocate to dissect starting on the preperitoneal plane in the epigastric area where we can reach the sub-diaphragmatic layer easily.13 Inferiorly the Bogros space can be dissected and advanced on the lateral preperitoneal fat where it is uncommon to have previous meshes.13 The dissection continues from lateral to medial to reach previous implanted meshes, then completing the posterior CS. The limits of our dissection in posterior CS are cranially, the central tendon of the diaphragm, caudally both Cooper ligaments and the pre-vesical space and laterally the psoas muscle. In rare cases of massive defects that required a large bridge otherwise, we associated an anterior CS to the previous steps.14 When the RM preperitoneal space is not technically feasible, we can use an external oblique release to close midline defects. In patients with a previous combination of absorbable and permanent synthetic mesh,15 we were able to free the space between the peritoneum and the synthetic mesh (Fig. 1).16 This maneuver enabled performing a “redo” preperitoneal repair. As previously detailed, we performed transversus abdominis release (TAR) as originally described or the Madrid posterior CS.7,17

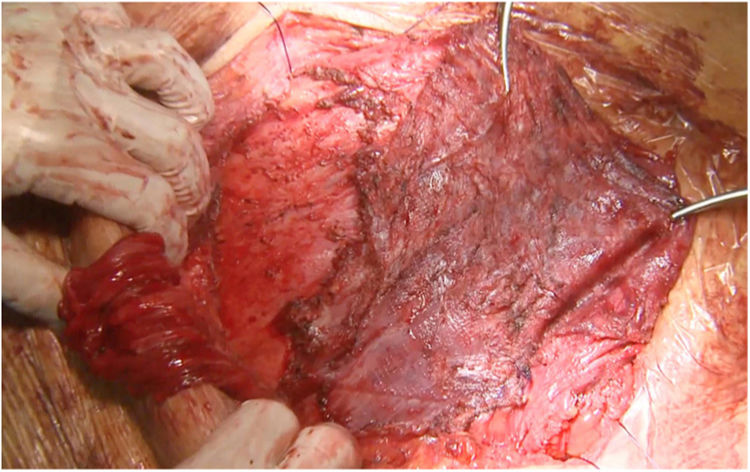

Most of the patients with lateral hernias that we reoperate after previous RM repair are the result of insufficient overlap of the previous mesh. We use the same previous incision if the lateral border of the posterior rectus sheath is not involved in the defect like in lumbar incisional hernias. When the hernia defect compromises the lateral border of the posterior rectus sheath, we advocate using a midline incision18 and perform a Madrid posterior CS. Our initial plan is to dissect once again the RM preperitoneal space, trying to keep the previous mesh attached to the muscle layers. This dissection is challenging as far as we reach an area that hasn’t been already accessed. We have observed that using a combination of absorbable and permanent meshes in the index procedure facilitates the dissection of the permanent mesh from the peritoneum, that otherwise is extremely laborious (Fig. 2).

In small size parastomal hernias EHS class I,19 we try to complete a Sugarbaker laparoscopic repair. When there is an associated midline hernia or significant parastomal hernia defect, our initial plan again is trying to dissect the RM space again and perform a Pauli repair.20 We perform an open Sugarbaker whenever it is impossible to access the RM or preperitoneal space.

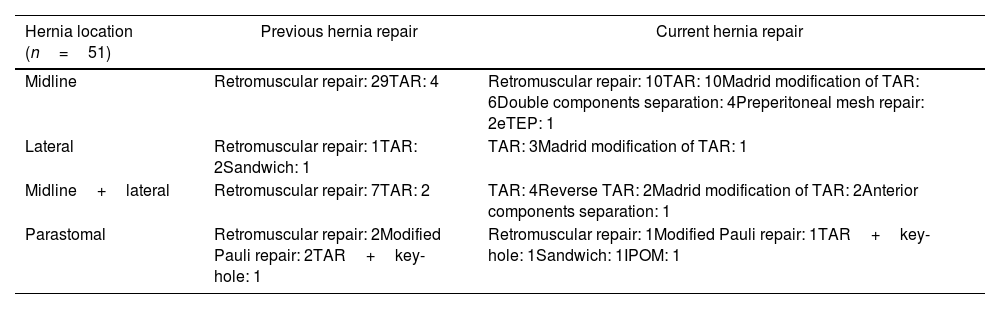

ResultsFifty-one patients complied with the criteria to be included in this study. Thirty-three patients had midline defects, 9 patients a combination of midline and lateral defect, 4 lateral defects alone and 5 patients parastomal hernia. As expected, we used a variety hernia repairs to treat these hernia recurrences (Table 1). We managed those patients with RM or preperitoneal repair in 13 patients. We employed posterior CS in 29 patients. We combined anterior and posterior CS in 4 patients. We chose extended totally extraperitoneal repair (e-TEP) in 1 patient and modified Pauli hernia repair in 1 patient, TAR and key-hole in 1 patient and intra-peritoneal mesh in 2 patients.

Hernia characteristics and repair.

| Hernia location (n=51) | Previous hernia repair | Current hernia repair |

|---|---|---|

| Midline | Retromuscular repair: 29TAR: 4 | Retromuscular repair: 10TAR: 10Madrid modification of TAR: 6Double components separation: 4Preperitoneal mesh repair: 2eTEP: 1 |

| Lateral | Retromuscular repair: 1TAR: 2Sandwich: 1 | TAR: 3Madrid modification of TAR: 1 |

| Midline+lateral | Retromuscular repair: 7TAR: 2 | TAR: 4Reverse TAR: 2Madrid modification of TAR: 2Anterior components separation: 1 |

| Parastomal | Retromuscular repair: 2Modified Pauli repair: 2TAR+key-hole: 1 | Retromuscular repair: 1Modified Pauli repair: 1TAR+key-hole: 1Sandwich: 1IPOM: 1 |

There have been 4 cases of urgent reoperation due to anastomotic dehiscence or bowel leak (Table 2). Two patients developed entero-atmospheric fistula. We operated one of them with good results and the other patient is under conservative treatment as it is yet too early to undergo definitive surgery. The other two patients did well with surgical treatment. One patient died on the postoperative course due to esophageal perforation related to previous large hiatal hernia. Regarding long-term results, we have found 3 patients with hernia recurrence: one patient with abdominal bulging after a lumbar incisional hernia and 2 parastomal recurrences, after keyhole repair and an ostomy prolapse after Pauli procedure.

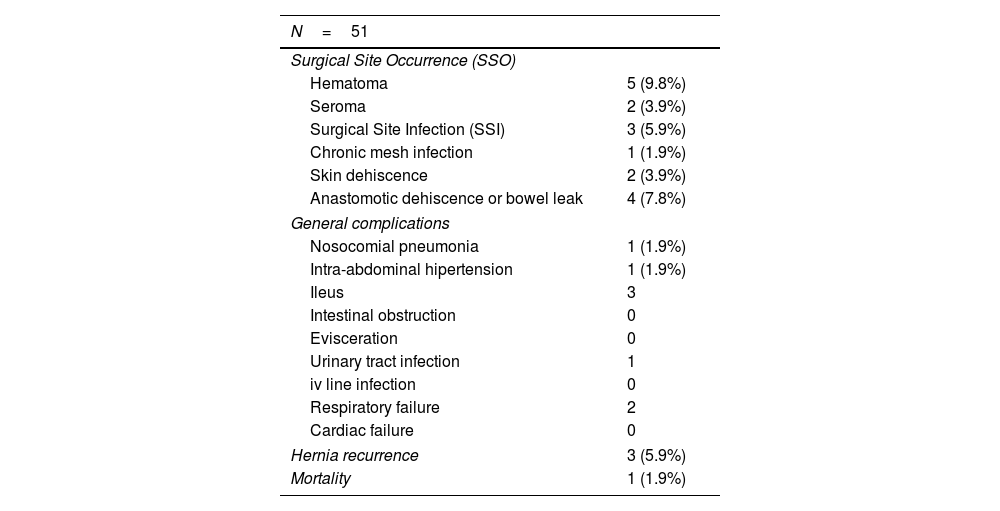

Postoperative complications.

| N=51 | |

|---|---|

| Surgical Site Occurrence (SSO) | |

| Hematoma | 5 (9.8%) |

| Seroma | 2 (3.9%) |

| Surgical Site Infection (SSI) | 3 (5.9%) |

| Chronic mesh infection | 1 (1.9%) |

| Skin dehiscence | 2 (3.9%) |

| Anastomotic dehiscence or bowel leak | 4 (7.8%) |

| General complications | |

| Nosocomial pneumonia | 1 (1.9%) |

| Intra-abdominal hipertension | 1 (1.9%) |

| Ileus | 3 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 0 |

| Evisceration | 0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 |

| iv line infection | 0 |

| Respiratory failure | 2 |

| Cardiac failure | 0 |

| Hernia recurrence | 3 (5.9%) |

| Mortality | 1 (1.9%) |

We describe a multicentre experience treating hernia recurrence after RM or posterior CS hernia repair. RM and posterior CS have an important role treating complex abdominal wall hernias. As its use as abdominal wall reconstruction is progressing, we expect an increase of hernia recurrences after those procedures. Novitsky et al. declared 4.7% recurrence rate at a median follow-up period of 26.1 months,7 but higher rates of recurrence have been published.3 We might address recurrences after previous RM repair and CS using multiple strategies, techniques and meshes. Warren et al. describe performing redo-TAR, redo-RM or intraperitoneal onlay mesh placement for patients with recurrent hernias after prior myofascial release.8 They stated that prior myofascial release does not preclude any other technique to repair hernia recurrences. However, they detailed that undergoing redo-RM took longer operative time and presented higher rates of intraoperative complications. Montelione et al. obtained satisfactory outcomes with redo-TAR for hernia recurrences but declared 22.5% recurrence rate, more than 5 times recurrence rate for index TAR.21 One of the most interesting concepts is that in some cases, it is impossible to close the posterior layer of the abdominal wall due to previous mesh removal or the lack of native tissue. In this setting, we have successfully used an intraperitoneal patch of absorbable mesh to close the peritoneum.15 Other authors have also used other absorbable meshes, omentum patch and even free peritoneal patch taken from sac remnants.22,23

Minimally invasive access with intra-peritoneal mesh placement is a reasonable alternative. Warren et al. communicate using intra-peritoneal onlay mesh (IPOM) in patients with hernia recurrence after prior RM repair, external oblique release and prior posterior CS.8 Similarly, Cobb et al. used laparoscopic access in a certain number of patients with recurrent incisional hernias.24

There are multiple challenging situations dealing with hernia recurrence after RM repair or prior CS. A new access to the retro-rectal space is particularly difficult due to the adhesions of the posterior rectus sheath, peritoneum and rectus abdominis muscle itself to the mesh. In this situation, peeling the mesh off the peritoneum may be impossible and the only affordable plane has to be switched to the retro-rectal plane itself (Fig. 2). In our experience, we consider leaving the mesh attached to the peritoneum and separate it from the muscle with a combination of blunt and electrocautery dissections. This circumstance is paramount to develop a wide dissection to insert a new mesh. If we feel that this space is not sufficient, then a posterior CS can be made progressing the dissection from lateral to medial to avoid adhesions to previous mesh.

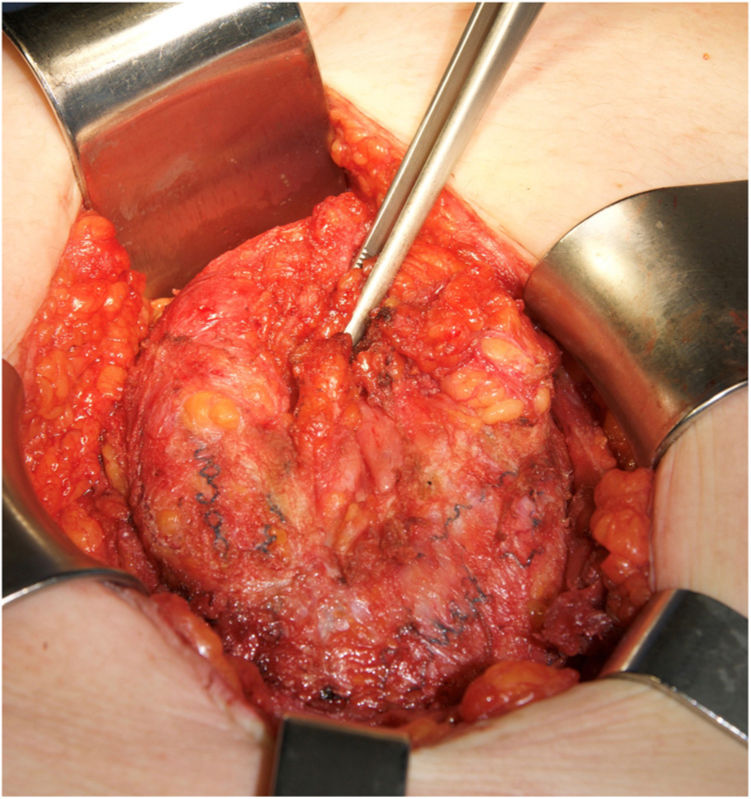

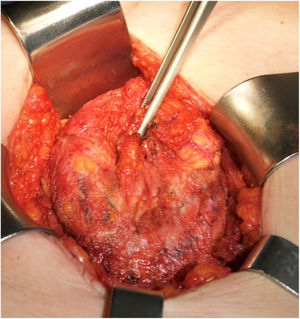

The main causes of hernia recurrence that we have found are disruption of the linea semilunaris, mesh breakdown (Fig. 3) and a defect beyond the mesh overlap. Those findings are coherent with similar etiologies in patients that required surgery for hernia recurrence.9,18 We have treated most of the midline defects with posterior CS. However, in 12 patients, another RM or preperitoneal repair was sufficient. We used double CS to treat massive defects. e-TEP or laparoscopic IPOM were preferred in 2 cases.

Warren et all suggested laparoscopic repair for hernia recurrences, in cases with defects smaller than 7cm.8 In the circumstance of greater defects, we can safely offer redo TAR. However, patients with redo TAR are complicated scenarios burdened with higher postoperative surgical site occurrences (SSO). We have found 11.5% surgical site infection rate which is almost seven times the rate after regular complex abdominal wall repair in our previous studies. In our series SSO rate was 33.3% that may not appear so high in these technically demanding situations.

We should also highlight that CS procedures require comprehensive knowledge of the abdominal wall anatomy and notably the different intermuscular planes and the proper way to access them. Preserving anatomical structures as the epigastric vessels and the neurovascular bundles that innervate the anterior abdominal wall are of paramount importance. Proctorship programs to enhance and promote proper abdominal wall reconstruction are strongly recommended25–27 in order to avoid terrible situations as disruption of linea semilunaris, recurrent for insufficient overlap or using unsuitable meshes.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, it is not a comparative study and therefore we cannot draw any conclusion. We should emphasize that posterior CS was described 10 years ago and these procedures are increasingly being used. Therefore, addressing hernia recurrences after those techniques have only been recently reported. Secondly, as this is a retrospective study, biases cannot be excluded. However, we detail the experience treating hernia recurrences after RM and posterior CS among three hospitals with specific Units to address complex abdominal wall hernias with similar approach, surgical procedures and follow-up.

ConclusionsTreating hernia recurrences after retromuscular or posterior components separation is a challenge. Several reconstructive techniques might be planed and adapted to patients with complex abdominal wall defects. We have widely used components separation procedures to treat this type of recurrences. Although technically challenging, reoperation of hernia recurrence after posterior component separation or retro-muscular repair should be considered in experienced centers with promising results, even though we may expect severe complications.

Authors’ contributionAll authors have read and approved the manuscript. In addition, have participated significantly in the design and development of the study.

Originality of the materialThe content of the article is original. This manuscript has not been previously published nor is it submitted or submitted for consideration to any other publication, in its entirety or in any of its parts.

Informed consentPatients have provided their consent for the use of data in scientific research, as well as reproduction of audiovisual media. Protocols have been followed established by the health centers to access the data of the clinical histories for the purpose of being able to carry out this type of publication with purpose of research/dissemination for the scientific community.

Conflict of interestAlvaro Robin Valle de Lersundi receives speaker fee from WL Gore & Associates. Javier Lopez-Monclus receives speaker fees from Medtronic, Dipromed and WL Gore & Associates. Luis A. Blazquez-Hernando receives speaker fees from Dipromed and WL Gore & Associates. Joaquin M. Munoz-Rodriguez receives speaker fee from Braun and WL Gore & Associates. Miguel A. Garcia-Urena received speaker fees from Medtronic, Bard, Dipromed, Dynamesh, Braun, Johnson and Johnson, Telabio and WL Gore & Associates and Medtronic. Manuel Medina Pedrique, Adriana Avilés Oliveros and Sara Morejón Ruiz have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.