Solid pseudopapillary tumors (SPT), which have been characterized by Hamoudi,1 represent 1%–2% of all pancreatic tumors. They are frequently incidental findings during ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) studies.2

The aim of this article is to present a new clinical case and provide updated information about this pathology.

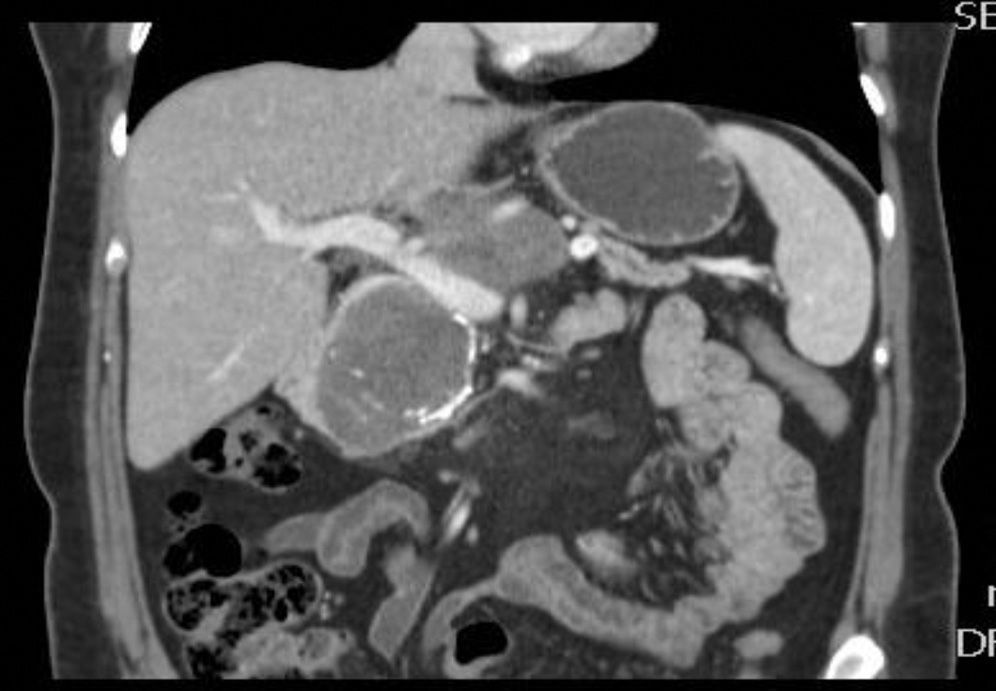

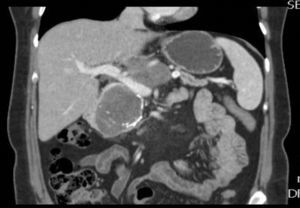

The patient is a 47-year-old woman, with no personal history of interest, who came to our consultation due to epigastralgia that had been growing progressively in intensity over the previous 2 months. Lab work-up showed no alterations and tumor levels were normal. Abdominal ultrasound detected a pancreatic mass measuring 10cm×6cm. CT scan showed evidence of a lesion in the head and body of the pancreas measuring 11cm×6cm×9cm that was predominantly solid, partially calcified, with heterogenous density and slight radiotracer uptake, and an irregular, poorly defined outline. The mass was compressing and displacing the splenoportal axis, which was completely surrounded. There was also extensive contact with the bifurcation of the celiac trunk with the common hepatic artery and splenic artery, which it surrounded by 50% (Figs. 1 and 2). Endoscopic ultrasound with cytology determined the mass to be an SPT.

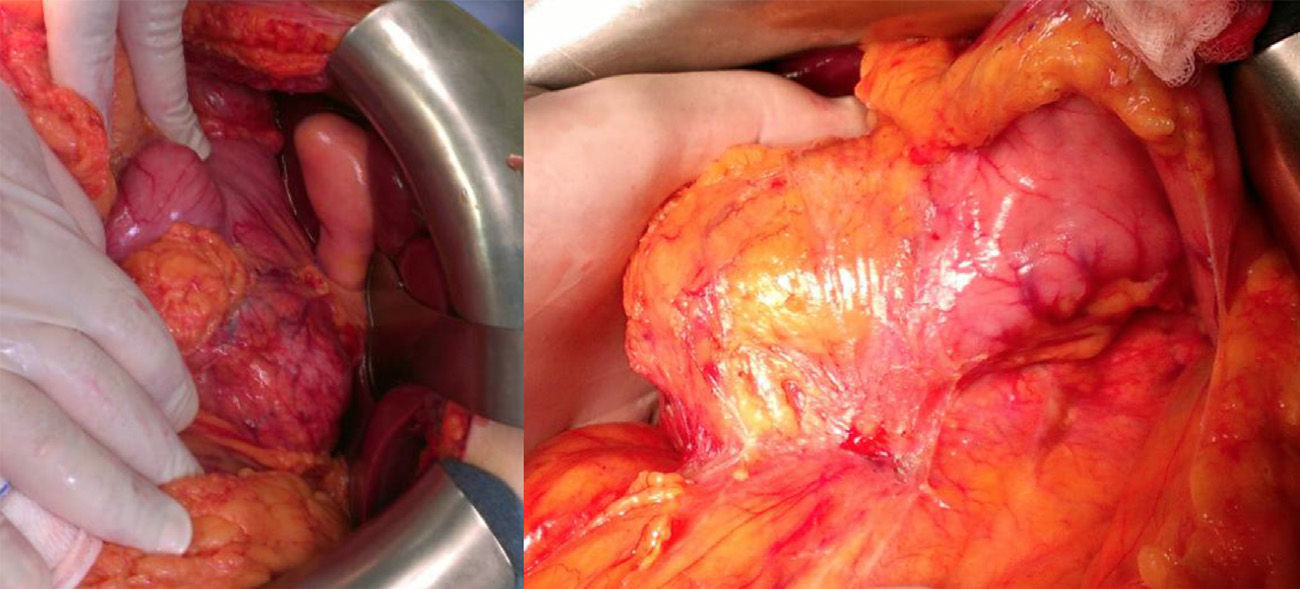

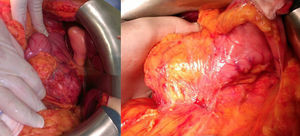

Using subcostal laparotomy, we located the tumor in the head/uncinate process/body of the pancreas (Fig. 3), encompassing the mesenteric-portal axis. Total pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed with splenectomy and lymph node dissection, without pylorus preservation. Venous reconstruction was done with a cadaveric mesenteric-portal vein Y graft measuring 7cm. Anastomoses were created to connect the 2 mesenteric vein ends to the Y graft and the other end to the portal vein. Afterwards, transmesocolic hepaticojejunostomy and gastrojejunostomy were performed in the same antecolic loop.

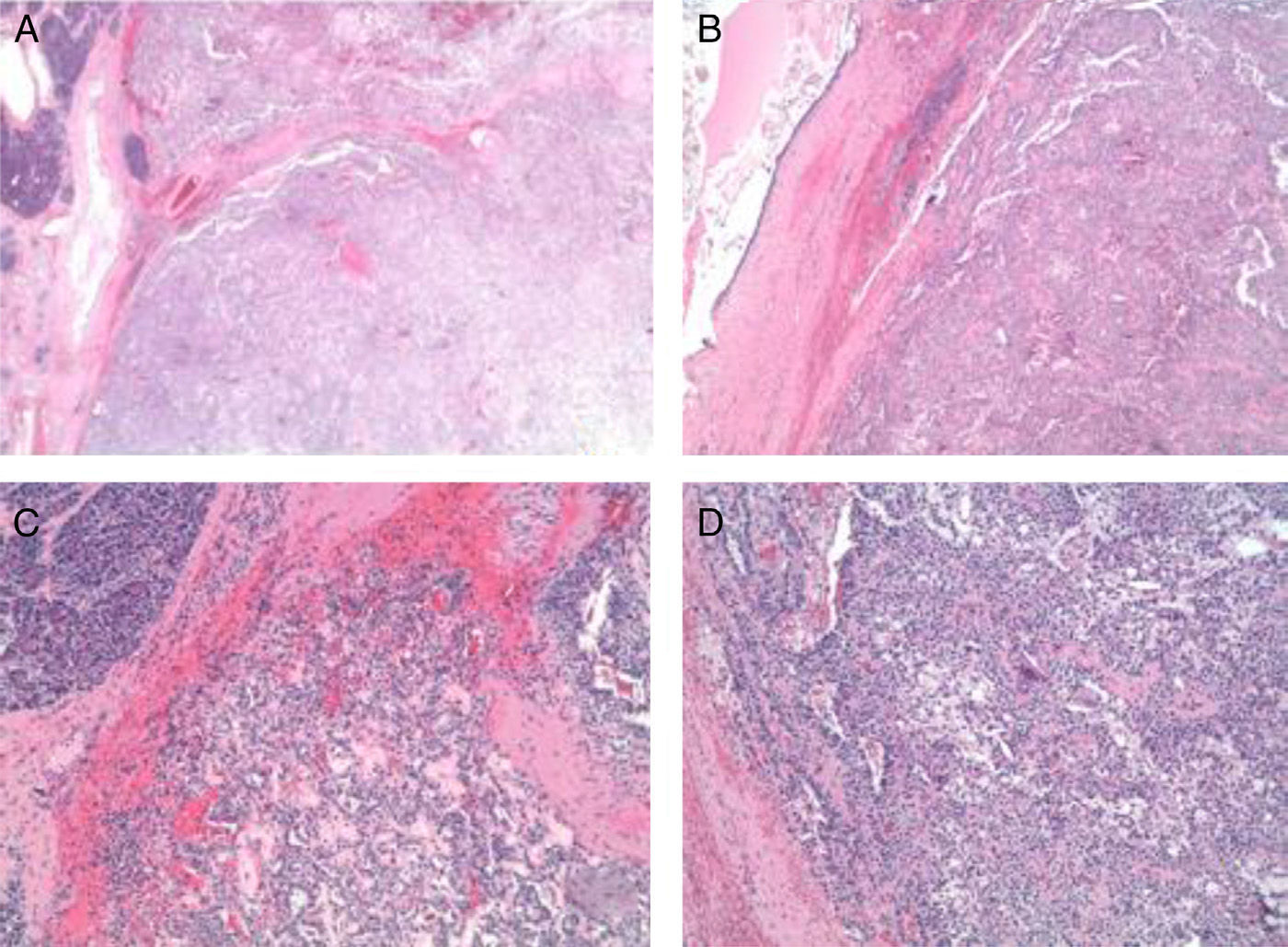

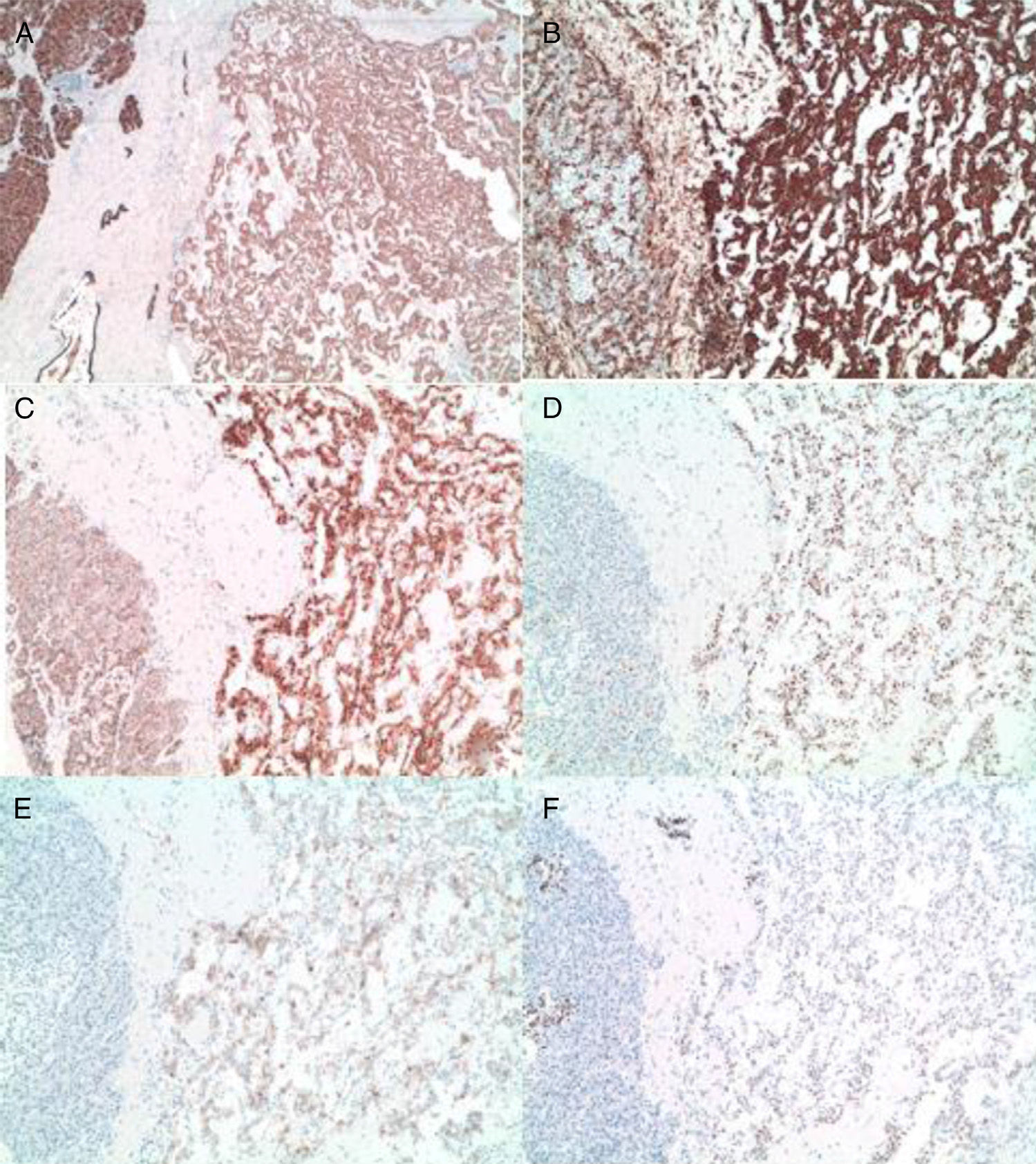

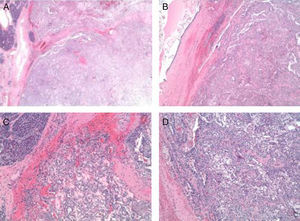

The pathology results (Figs. 4 and 5) reported an epithelial mass that was solid-cystic, pseudoencapsulated and heterogeneous. The neoplastic cells formed pseudopapillary structures with long, fibrotic, vascularized connective axes. There was no atypia and few mitoses. The more solid areas had macrophage foam cell aggregates surrounded by cholesterol crystals and multinucleated giant cells. There were signs of stromal calcification with degenerated areas. No structures with poor prognosis were observed. Ki-67 was 1%–2%. Immunohistochemistry techniques (Fig. 6) defined it as an SPT with reactive lymphadenitis (0/16).

(A) Panoramic macro/micro images of the tumor lesion with normal adjacent pancreatic acinar tissue; (B) and (C) images in HE 4× and 10× of solid and pseudopapillary areas of the tumor; (D) cytology (10×) of the tumor cells with presence of macrophage cells, giant cells and cholesterol crystals.

(A) and (B) Diffuse and intense expression of cytokeratin AE1.3 and vimentin of the tumor cells (10×); (C) nuclear and cytoplasmic overexpression of B-catenin (10×); (D) nuclear translocation of cyclin D1 (10×); (E) and (F) expression of CD 10 and progesterone receptors in the tumor cells (10×).

The patient's later progress was good, but imaging studies demonstrated a thrombosis of the portal axis that did not affect liver function.

The etiology of SPT is unknown. The male:female ratio is 1:9.5, and these tumors usually appear in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life.3–6 Clinical manifestations are abdominal pain (as in our case), palpable mass, dyspepsia, fullness, jaundice, nausea, vomiting and weight loss.3

These tumors may also be incidental findings during complementary studies, such as ultrasound and/or CT done for various reasons.5,7 The most frequent location is the head of the pancreas (39.8%), followed by the tail (24.1%). As in our patient, CT shows less uptake in the center of the cysts and increased uptake in the solid surrounding areas. Calcifications are also characteristic.7

Currently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is better than CT for detecting the solid or cystic components of the tumor,1,5,7,8 as well as cystic degeneration.1 In the series by Guo et al.,8 there were degenerative changes in the 24 cases reported. Although tumor characterization is high in this type of tumors using imaging tests, histology studies with cytology or Tru-Cut biopsy are a great help in differentiating pancreatic pseudopapillary tumors from other tumors, as occurred in our case.

The review by Yu et al.6 recorded 553 cases in 13 years. There was suspicion or diagnosis before surgery in only 77 patients, demonstrating that CT and MRI combined with age and patient gender are sufficient to indicate surgery, while interventional procedures should only be done when there is an uncertain diagnosis and in tumors smaller than 3cm.6,8,9

Macroscopically, these tumors are yellowy-brown and soft in consistency. On the cut surface, there are solid, hemorrhagic, necrotic and cystic areas, mainly compromising the tail of the pancreas.4

Immunohistochemistry is positive for: vimentin, α-1-antitrypsin, α-1-antichymotrypsin, neuronal specific enolase, CD 10 and progesterone receptors (our case), and close to 75% also express cyclin D1.2,6,7

Radical resection is the treatment of choice, even with metastasis or local recurrence.4–6 Lymph node dissection is not recommended.6

Prognosis is good, with low local recurrence (<10%), metastasis or local invasion, as these tumors have a low malignant potential.4,5,7 Guo et al.8 mentioned that 20/22 patients with a mean follow-up of 68 months had no evidence of disease recurrence, which was similar to Slako et al.1

SPT are tumors with a low malignant potential. Their etiology is unknown, although there is a strong relationship with female sex hormones. Diagnosis before surgery continues to be a challenge for physicians. In patients with a solid-cystic encapsulated mass with hemorrhagic degeneration, calcifications and solid lesion uptake, SPT should be included in the differential diagnosis. Currently, MRI is the study of choice for diagnosis. The treatment of choice is radical surgical resection, which provides a 5-year survival rate of 95%.

Please cite this article as: Leonher-Ruezga K, Lopez-Espinosa S, Moya Herraiz A, Perez Rojas J, López Andújar R. Tumor seudopapilar sólido del páncreas: presentación de un caso y revisión del tema. Cir Esp. 2015;93:e37–e40.