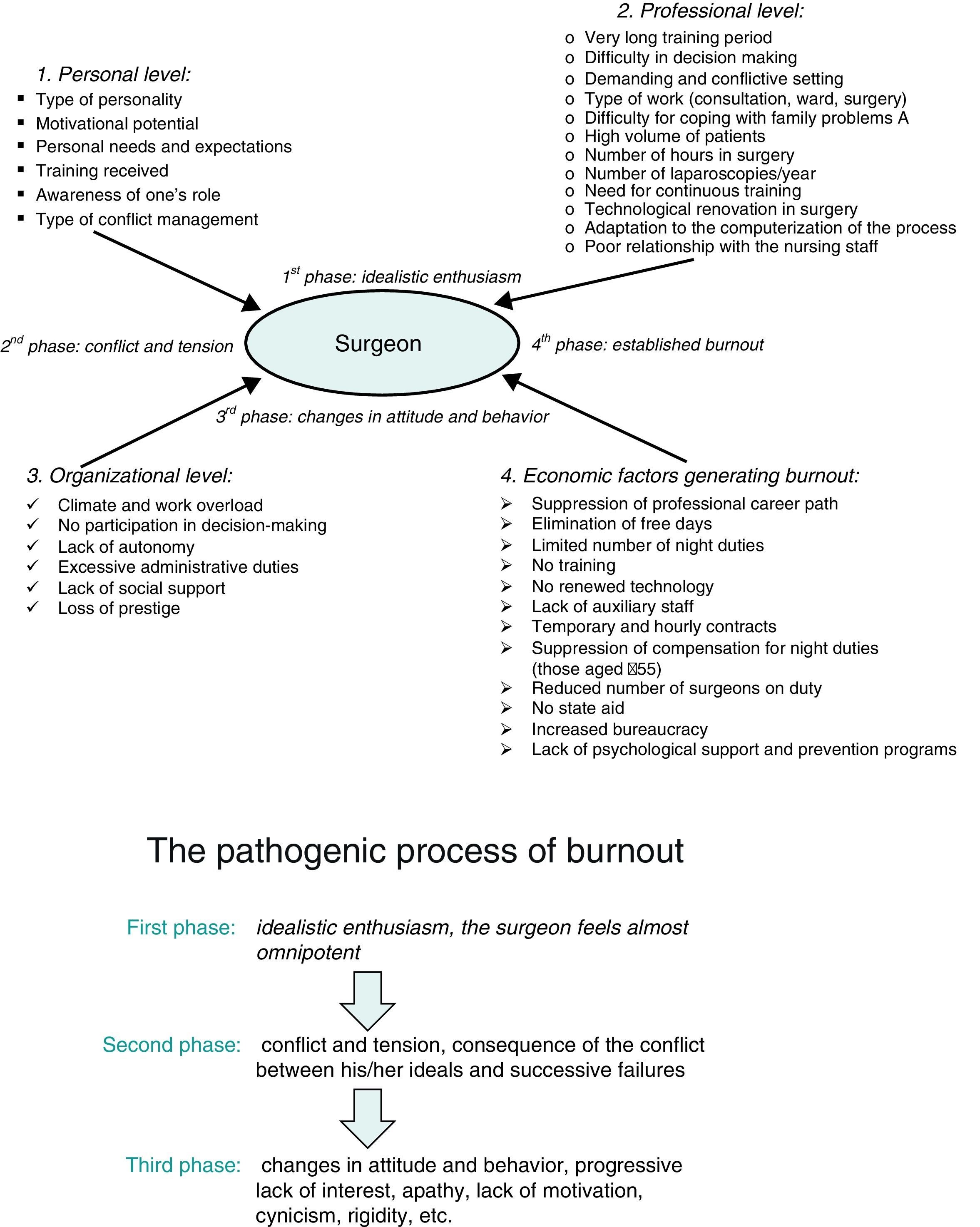

The fact that burnout among surgeons is a current problem is of no surprise, and in the past year many articles have been published on the subject. Burnout syndrome can be defined as a situation of emotional overload among professionals who, after many years of dedication, become burned out and present excessive emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and lack of interest in work.2 The true prevalence of this affectation among surgeons is unknown, although it may range between 30% and 80% as this collective is one of the highest risk groups compared with other medical specialties.3–6 The etiological factors involved in its genesis have been related with the number of work hours, mid-night calls, patient volume, high patient expectation, poor relationship with the nursing staff, lack of autonomy, administrative red tape, job- and family-related problems, excessive amount of paperwork, lawsuit abuse, the number of laparoscopic interventions, etc.4–7 To these factors, we must now include the added stress originating from the current economic situation, and unjustified, abrupt changes in working conditions: forced early retirement, elimination of compensation for night duty (for those aged >55), temporary contracts, loss of career paths (which, with great effort, had improved in some Spanish provinces), lack of training resources, lack of cutting-edge technology, loss of on-call and on-duty physicians, suspension of outsourcing, loss of influence over some patients and increasingly-demanding family members, etc. (Fig. 1).

The characteristics of surgeons’ jobs make this collective one of the most affected by this latent disease and the new reality of working conditions brought on by economic problems, caused by political mismanagement and long-term overspending in many other fronts that have nothing to do with healthcare or healthcare professionals. In this collective, there have been unavoidable mid-term consequences in both work performance (medical errors and lawsuits) and health (sick leaves).

In this difficult social situation, it would seem that surgeons are being portrayed as privileged and earning loads of money, although nothing could be further from the truth. But, what if it were true? Who else does what we do? It seems that many would like to be surgeons when good money is involved, but who wants to work a 24-h shift on New Year's, your son's first communion, the school play, the day of the big game or your wedding anniversary? And what about when the call wakes you in the middle of the night because of a car accident and you have to operate on a child with an open abdomen, or an obstruction due to advanced-stage cancer, or massive hemorrhaging from an aneurism that you have to fight for hours to control (with whatever you have at hand)? Who, then, wants to be a surgeon?1 Just one data from a pioneering country in medical training (USA) is enough to demonstrate that general surgery is losing its charm: in the last 25 years, the number of general surgeons per 100000 inhabitants has dropped 25%.4

The situation in our country is aggravated by the fact that our healthcare system has shown the world that it is one of the most efficient, with less healthcare professionals per inhabitant and resident training programs that have made our physicians desirable for their quality and dedication.

So, what is happening now? The economic crisis has brought about changes in hospital administration that were approved in record time and are an unfair and undeserved surprise for healthcare professionals, which will have direct repercussions on all of us (we are human, after all). The loss of participation in the decision-making process has generated incomprehensible differences among professionals from different autonomous communities and even among hospitals in the same community. The perception of general surgeons in Spain as privileged professionals no longer exists (if it ever really existed) and medical students as well as residents are aware of it. The effort and dedication that medical careers require are incomprehensible for the new generations. Today, only those who feel a true calling for surgery would choose this type of life. And, with the current situation, is anyone worrying about the surgeon now? Stress, depression, anxiety, burnout and the lack of a sense of fulfillment are all quietly waiting in the operating rooms of this country to ruin the lives of hundreds of surgeons who have dedicated most of their lives to helping others. The future has turned gray and uncertain.

For several decades, the Spanish healthcare system has boasted of having the best professionals and has been the envy of many countries in our region. Now, residents will have to closely look at where to be trained: economic factors (money and future possibilities) will surely weigh more than the quality of their training; their possibilities will be limited merely by where they are; administrators are not going to find doctors willing to collaborate for free with a system of administration that does not take them into account and on whom their whole civil service bureaucracy and inflexibility depends; research and training will fall by the wayside (as they do not produce money, only spending). The influence of this climate on the already-stressful work of surgeons will lead to changes in behavior patterns: surgeons may start to lose their moral and social connection with their work and work environment as a necessary defense mechanism; soon after, behaviors will emerge that, over time, will predispose them to burnout. In one or two generations, our society will be cared for by professionals who are clearly less qualified and committed.4

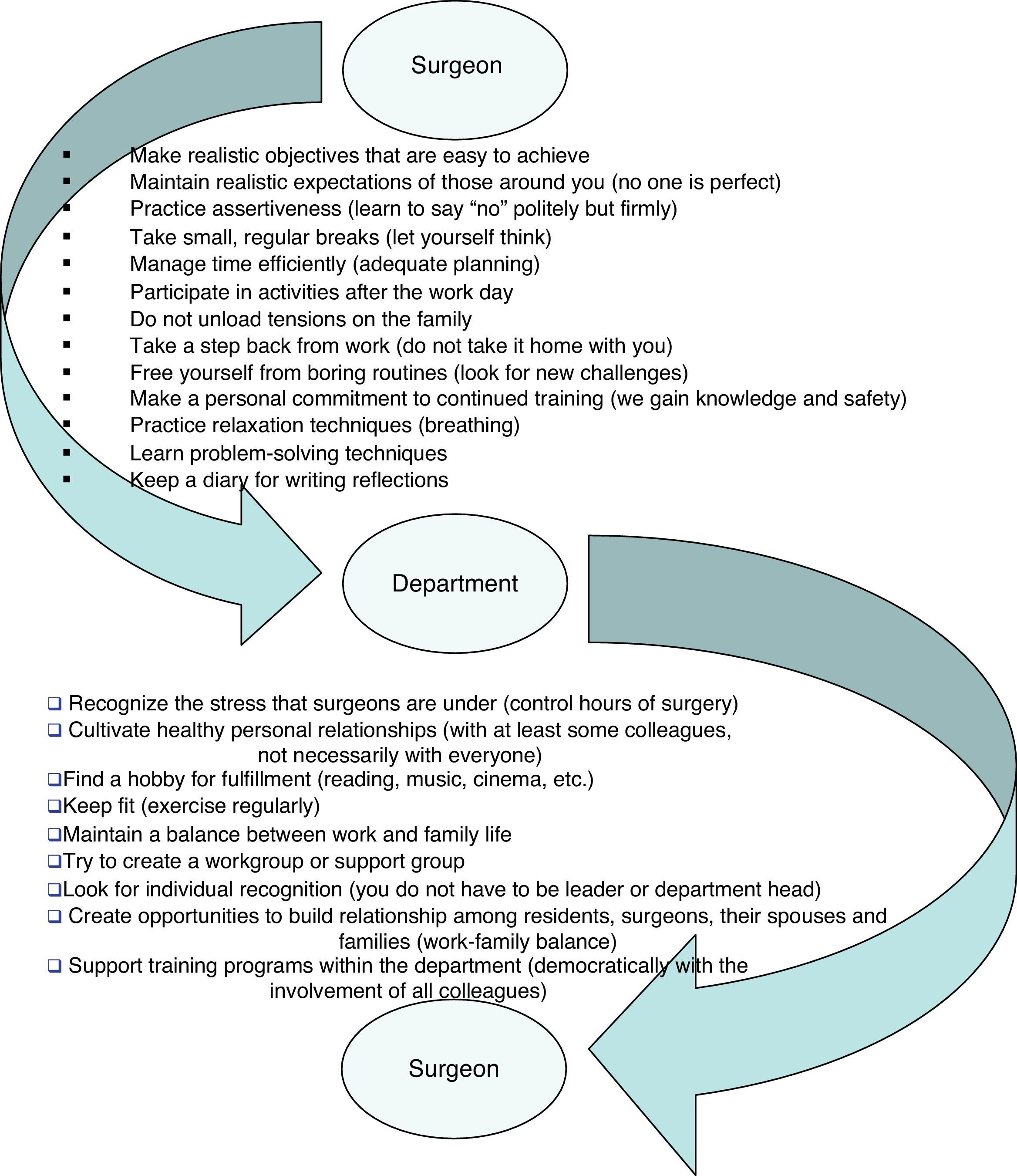

What can be done to balance this process? It is clear that we will not be able to depend on state measures. The only protection for surgeons will come from themselves and their fellow colleagues (work groups, departments, associations, societies, etc.). Individual coping measures become more necessary, but these greatly depend on the ability of each person's personality to use them and to adequately manage his/her situation: family, financial situation, personal satisfaction, ideals, self-control. All these factors will be more necessary than ever to buffer the path toward chronic fatigue and burnout (Fig. 2).8–10 May these lines be a warning that we are all putting our health and well-being at risk. We should all start to take care of ourselves because nobody else is going to for many years to come.

To Dr. J.C. Mayagoitia González, vice president of the Mexican Association of Surgeons. Paper developed in part for the closing conference of the 3rd International Congress of Surgeons, México, 2012.

Please cite this article as: Moreno-Egea A. Cirujanos, crisis económica y burnout. Cir Esp. 2013;91:137–40.