The refusal rate for donating organs among the Roma people is much higher than that of any other social group.

ObjectiveTo analyze the attitude towards the donation of one's own organs among the Roma population living in Spain.

Method. Type of study: Spanish national observational sociological study stratified by gender and age. Study population: Roma population aged ≥15 years living in Spain. Sample size: 1,253 respondents. Assessment instrument: Validated questionnaire on attitude towards organ donation for transplantation "PCID - DTO Ríos". Field work: Random selection based on stratification. Anonymous and self-administered completion. The collaboration of people of Roma ethnicity was required. Statistics: Student's t test, χ2, Fisher’s exact test and a logistic regression analysis.

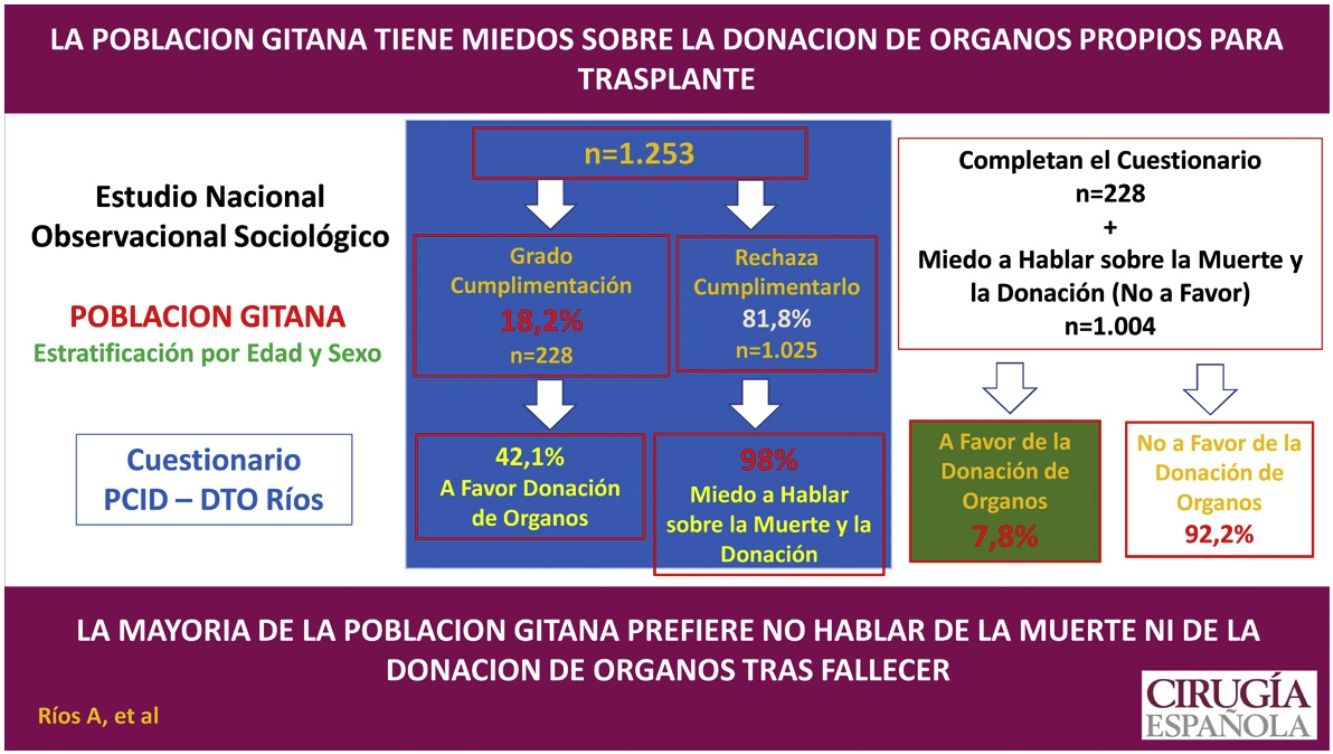

ResultsThe degree of completion was 18.2% (n = 228). Of those who completed the questionnaire, 42.1% (n = 96) were in favor of donation, 30.3% (n = 69) were undecided and the remaining 27.6% (n = 63) were against it. Of the 1,025 (81.8%) who declined to complete the questionnaire, 1,004 (98%) indicated that it was for fear of speaking about and filling in a questionnaire that raises the issue of death and organ donation after death. If those who did not complete the questionnaire due to fear of death and donating organs after death are considered not in favor, the results would be as follows: 7.8% (n = 96) in favor of donating their organs compared to 92.2% (n = 1166) not in favor (against or undecided).

ConclusionsA majority of the Roma population prefer not speak of death nor organ donation after death. These findings show that current campaigns to promote organ donation are not effective in this population group.

La tasa de negativas a la donación entre el pueblo gitano es muy superior a la de cualquier otro grupo social.

ObjetivoAnalizar la actitud hacia la donación de los órganos propios entre la población gitana residente en España.

MétodoTipo de estudio: Estudio sociológico observacional nacional español estratificado por género y edad. Población a estudio: Población gitana con edad ≥15 años residente en España. Tamaño muestral: 1.253 encuestados. Instrumento de valoración: Cuestionario validado de actitud hacia la donación de órganos para trasplante “PCID - DTO Ríos”. Trabajo de campo: Selección aleatoria en función de la estratificación. Cumplimentación anónima y autoadministrada. Fue precisa la colaboración de personas de étnia gitana. Estadística: Tests de t de Student, χ2, Fisher y un análisis de regresión logística.

ResultadosEl grado de cumplimentación fue del 18,2% (n = 228). De los que han cumplimentado el cuestionario, están a favor de la donación el 42,1% (n = 96%), indeciso el 30,3% (n = 69) indecisos, y en contra el 27,6% restante (n = 63). De los 1.025 (81,8%) que rechazaron cumplimentar el cuestionario, 1.004 indicaron que era por miedo a hablar y rellenar un cuestionario que plantee el tema de la muerte y la donación de órganos tras fallecer. Si se consideran que los que no han cumplimentado el cuestionario por miedo a la muerte y la donación de órganos tras fallecer no están a favor, los resultados serían los siguientes. El 7,8% (n = 96) a favor de donar sus órganos frente al 92,2% (n = 1.136) no a favor (en contra o indecisos).

ConclusionesLa población gitana presenta un rechazo mayoritario a plantear el tema de la muerte y la donación de órganos tras fallecer. Estos hallazgos muestran que las campañas actuales para promover la donación de órganos no son efectivas en este grupo de población.

Spain has highest organ donation rates in the world, despite the drop as a result of COVID-19.1,2 However, there are options for improvement, both in the search for new sources of organs and in identifying social groups with low awareness.3–6 The inclusion of Maastricht type III asystole donation has led to an increase of more than 10 points in organ donation rates in the last 5 years.1 Different social groups with low awareness of organ donation and transplantation have been analysed, particularly immigrant groups.3–6

The Roma population are a social group with low organ donation rates. However, there are no studies that analyse this problem or determine the factors underlying it. An aspect considered fundamental is the weight that the image of death has in this social group.7–9 Death is considered a taboo, there is an irrational fear of the subject, and it is not talked about. The Roma ethnic group has cultural, psychosocial, and religious attitudes towards death and related aspects such as organ donation.7,8 In this population group, therefore, death has a marked symbolism and social meaning with specific funeral and mourning rites.

Although considerable progress has been made over the last two decades,7–10 the Roma are still poorly socially integrated and difficult to access. This influences undertaking psychosocial studies among them. The large number of psychosocial studies on organ donation and transplantation carried out in different social groups3–6 and the lack of any in the Roma ethnic group are striking. The first attempts of our research group highlighted the difficulty of approaching this group11; Roma with university education12 were easier to approach and discuss living donation13 or experimental transplantation,14 avoiding the issue of organ donation after death.11 However, the Roma’s perception of the process of organ donation and transplantation and the psychosocial factors that influence it are important in the design of educational interventions aimed at improving their attitude to donation.

The aims of this study are: (1) To discover how the attitude towards organ donation after death is structured in the Roma population, (2) To analyse the psychosocial variables that determine it, and (3) To define the psychosocial profiles that are favourable and unfavourable towards organ donation.

Material and methodsStudy typeObservational, cross-sectional study in Spain.

Study populationThe study population is comprised members of the Roma population aged 15 years or older resident in Spain.

There is no official census from which data can be obtained on the Roma ethic group. Therefore, to estimate this population, the estimates of the VIII FOESSA report,8 the estimates of the housing maps conducted by the Fundación Secretariado,15,16 and those of the European Roma and Travellers Forum17 are taken as the benchmark. Based on these, it is estimated that 558,000 Roma live in Spain, which represents 1.57% of the total population.

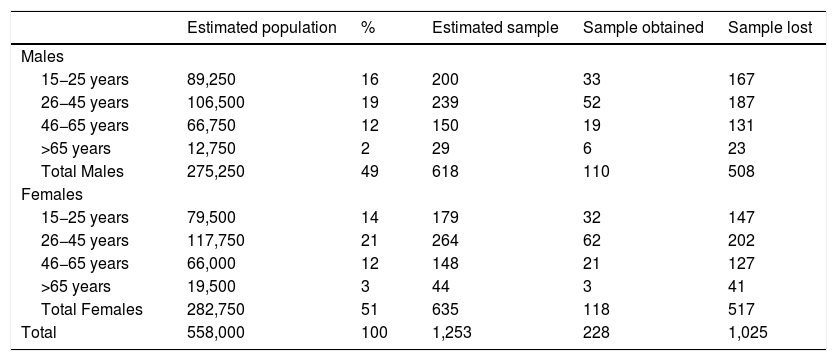

Sample size and stratificationThe sample size for this population (n = 558.000) and considering an attitude in favour of the 50% of respondents, was 1.253 people, with a confidence level (1-α) of 95% and an accuracy (d) of 3%, considering a loss ratio (R) of 15%.

The sample was stratified according to the gender and age of the study population:

- 1

Stratification by gender. Male or female

- 2

Stratification by age. Groups were formed according to age range: 15−25 years, 26−45 years, 46−65 years, and ≥65 years (Table 1).

Table 1.Stratification of the Roma population sample by age and gender, and degree of completion of each stratum.

Estimated population % Estimated sample Sample obtained Sample lost Males 15−25 years 89,250 16 200 33 167 26−45 years 106,500 19 239 52 187 46−65 years 66,750 12 150 19 131 >65 years 12,750 2 29 6 23 Total Males 275,250 49 618 110 508 Females 15−25 years 79,500 14 179 32 147 26−45 years 117,750 21 264 62 202 46−65 years 66,000 12 148 21 127 >65 years 19,500 3 44 3 41 Total Females 282,750 51 635 118 517 Total 558,000 100 1,253 228 1,025

The measurement instrument was a validated questionnaire on attitudes towards organ donation and transplantation (PCID-DTO RIOS: The “Proyecto Colaborativo Internacional Donante”` ["International Collaborative Donor Project"] questionnaire on organ donation and transplantation created by Dr Ríos).18,19 This questionnaire includes questions distributed in four sub-scales validated at population level, with a total explained variance of 63.203% and a Cronbach's Alpha Reliability Coefficient of .834.

Pilot studyGiven their unique characteristics, a pilot study was conducted to gauge how best to approach the Roma population. The patriarch, or Roma leader, was contacted in three Roma groups, to whom the project was explained, and who agreed to participate in the pilot study.

Two different approaches were considered:

- 1

Direct approach (n = 100). By personal interview. The interviewer explains the project and gives the questionnaire to the potential respondent.

- 2

Indirect approach (n = 200). For greater anonymity of the potential respondents, at a meeting or meeting point of the group, the representative of the group explained the project, where the questionnaire was and the voluntary nature of completing it. The questionnaires were collected at the end of the meeting.

In both groups the questionnaires were self-completed. Completion of the questionnaires was anecdotal in both groups.11 The direct approach presented many problems, with low participation (n = 12) and when attempts were made to generate empathy to improve completion rates, there was a somewhat hostile response. In the indirect approach, only 10 questionnaires were obtained, 9 were blank or inked in.

It can be concluded from the pilot study that approaching the Roma population is complex, and therefore an approach supported by Roma leaders is necessary.11

FieldworkThe Roma population is distributed throughout Spain. However, this distribution is not homogeneous. Thus, 45% of the Roma population resides in Andalusia, and the rest principally in the four Autonomous Communities of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, and Murcia (where 50% of the Roma population resides).

In each of the population centres where the sampling was to be conducted, the collaboration of the Roma population was required to accompany the collaborators of the International Donor Collaborative Project to gain access to the potential respondents. In each case, it was confirmed that the potential respondent met the age and gender stratification criteria. It was explained to the respondents that this was a completely anonymous opinion survey and oral consent to the survey was sought. In no case were respondents offered incentives to participate in the project. The questionnaire was completed anonymously and self-administered.

The collaborators trained in basic skills to empathise with the respondents, primarily to convey the idea that this was a totally anonymous project to improve health. Any confrontation was always avoided. If respondents did not want to participate in the Project, they were asked to give their reason.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (CE012116). Consent to participate was oral, and the consent of legal guardians was required for people under the age of 18.

Study variablesThe dependent variable studied was the attitude towards own organ donation after death. The independent variables were grouped into the following categories: (1) Sociopersonal variables; (2) Variables on knowledge about donation and transplantation; (3) Social interaction variables; (4) Religious variables; and (5) Variables on attitude towards the body.

StatisticsThe data were stored in a database. Descriptive statistics were performed, and the Student's t-test and χ2 test were used to compare the different variables. To determine and evaluate multiple risks a logistic regression analysis was performed using the variables that in the bivariate analysis gave statistically significant associations.

ResultsLevel of completion and attitude towards cadaveric organ donationThe level of completion of the questionnaire was 18.2% (228 respondents out of 1,253 selected), and was similar between men and women (17.8% versus 18.6%) (Table 1). By age range, the completion rate was 17.2% (n = 65) among those aged 15−25 years, 22.7% (n = 114) among those aged 26−45 years, 13.4% (n = 40) among those aged 46−65 years, and 12.3% (n = 9) among those aged 65 years or older.

Attitude towards cadaveric organ donationIn 81.8% of the survey attempts (n = 1,025) the potential respondents refused to fill in the questionnaire. Of the 1,025 who refused to fill in the questionnaire, 1,004 indicated that it was because they were afraid to talk about and fill in a questionnaire that raises the issue of death and organ donation after death. The remaining 21 gave no or different reasons.

Of the 228 completed questionnaires obtained, the opinion towards organ donation after death was favourable in 42.1% of the questionnaires (n = 96), unfavourable in 27.6% (n = 63) and undecided in the remaining 30.3% (n = 69).

If those who did not fill in the questionnaire because of fear of death and organ donation after death are considered not to be in favour, the results would be as follows. 7.8% (n = 96) in favour of organ donation compared to 92.2% (n = 1,136) not in favour (against or undecided).

Factors determining attitudes towards organ donationGiven the low completion rate, determining factors associated with attitudes towards organ donation after death loses much of its value. Nevertheless, we performed a bivariate analysis.

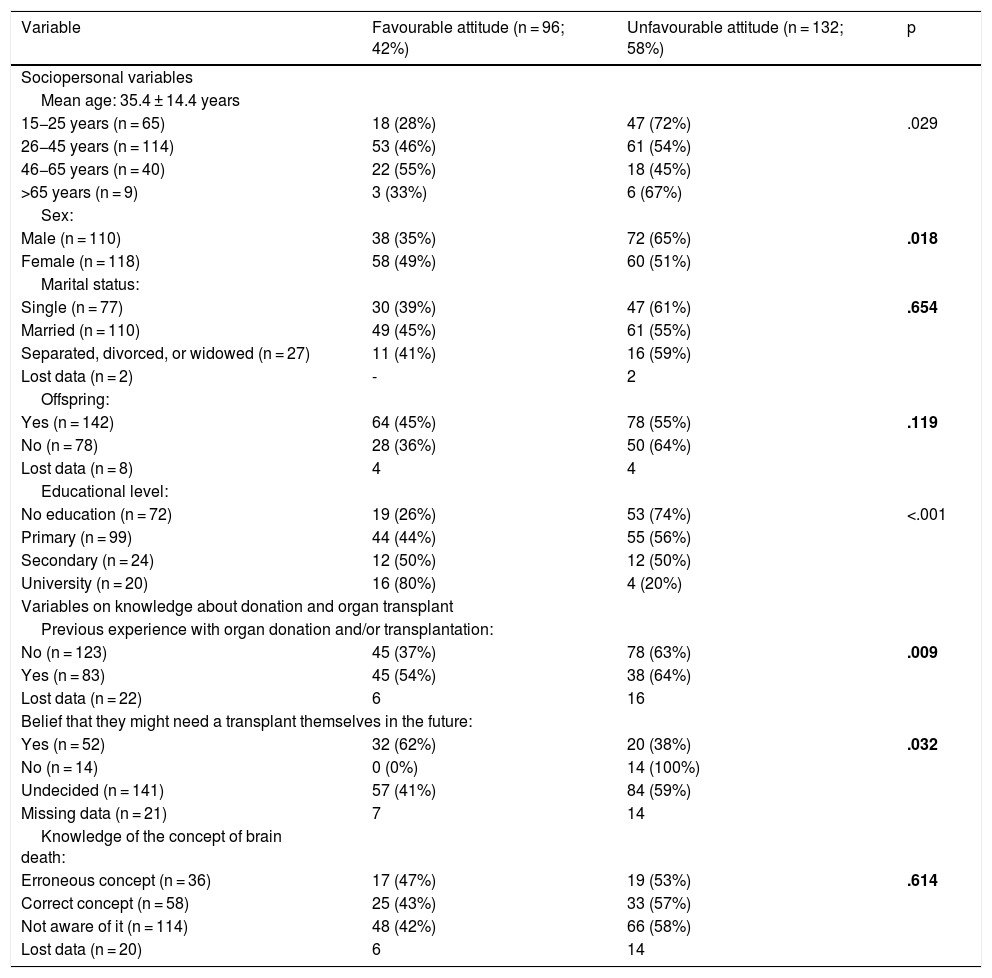

Socio-Personal variablesAttitude towards donation is associated with age. Thus, respondents in the intermediate age groups, 26−45 years, and 46−65 years, have a more favourable attitude than the younger and the older respondents (47% and 55% in favour versus 26% and 33%, respectively; p = .029; Table 2). In terms of gender, the attitude is more favourable among women (49% versus 35%; p = .018). Finally, differences were observed according to level of education. Thus, 61% of those with university education were in favour of organ donation compared to 13% of those with no education (p < .001; Table 2).

Sociopersonal variables and variables on knowledge about organ donation and transplantation that are associated with attitudes towards organ donation after death among the Roma population.

| Variable | Favourable attitude (n = 96; 42%) | Unfavourable attitude (n = 132; 58%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociopersonal variables | |||

| Mean age: 35.4 ± 14.4 years | |||

| 15−25 years (n = 65) | 18 (28%) | 47 (72%) | .029 |

| 26−45 years (n = 114) | 53 (46%) | 61 (54%) | |

| 46−65 years (n = 40) | 22 (55%) | 18 (45%) | |

| >65 years (n = 9) | 3 (33%) | 6 (67%) | |

| Sex: | |||

| Male (n = 110) | 38 (35%) | 72 (65%) | .018 |

| Female (n = 118) | 58 (49%) | 60 (51%) | |

| Marital status: | |||

| Single (n = 77) | 30 (39%) | 47 (61%) | .654 |

| Married (n = 110) | 49 (45%) | 61 (55%) | |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed (n = 27) | 11 (41%) | 16 (59%) | |

| Lost data (n = 2) | - | 2 | |

| Offspring: | |||

| Yes (n = 142) | 64 (45%) | 78 (55%) | .119 |

| No (n = 78) | 28 (36%) | 50 (64%) | |

| Lost data (n = 8) | 4 | 4 | |

| Educational level: | |||

| No education (n = 72) | 19 (26%) | 53 (74%) | <.001 |

| Primary (n = 99) | 44 (44%) | 55 (56%) | |

| Secondary (n = 24) | 12 (50%) | 12 (50%) | |

| University (n = 20) | 16 (80%) | 4 (20%) | |

| Variables on knowledge about donation and organ transplant | |||

| Previous experience with organ donation and/or transplantation: | |||

| No (n = 123) | 45 (37%) | 78 (63%) | .009 |

| Yes (n = 83) | 45 (54%) | 38 (64%) | |

| Lost data (n = 22) | 6 | 16 | |

| Belief that they might need a transplant themselves in the future: | |||

| Yes (n = 52) | 32 (62%) | 20 (38%) | .032 |

| No (n = 14) | 0 (0%) | 14 (100%) | |

| Undecided (n = 141) | 57 (41%) | 84 (59%) | |

| Missing data (n = 21) | 7 | 14 | |

| Knowledge of the concept of brain death: | |||

| Erroneous concept (n = 36) | 17 (47%) | 19 (53%) | .614 |

| Correct concept (n = 58) | 25 (43%) | 33 (57%) | |

| Not aware of it (n = 114) | 48 (42%) | 66 (58%) | |

| Lost data (n = 20) | 6 | 14 | |

In bold: statistically significant values.

The respondents with previous experience of organ donation or transplantation, through family or friends, had a more favourable attitude than those with none (54% versus 37%; p = .009). In the same sense, those who considered they might need a transplant themselves in the future had a more favourable attitude (62% versus 0%; p = .032; Table 2).

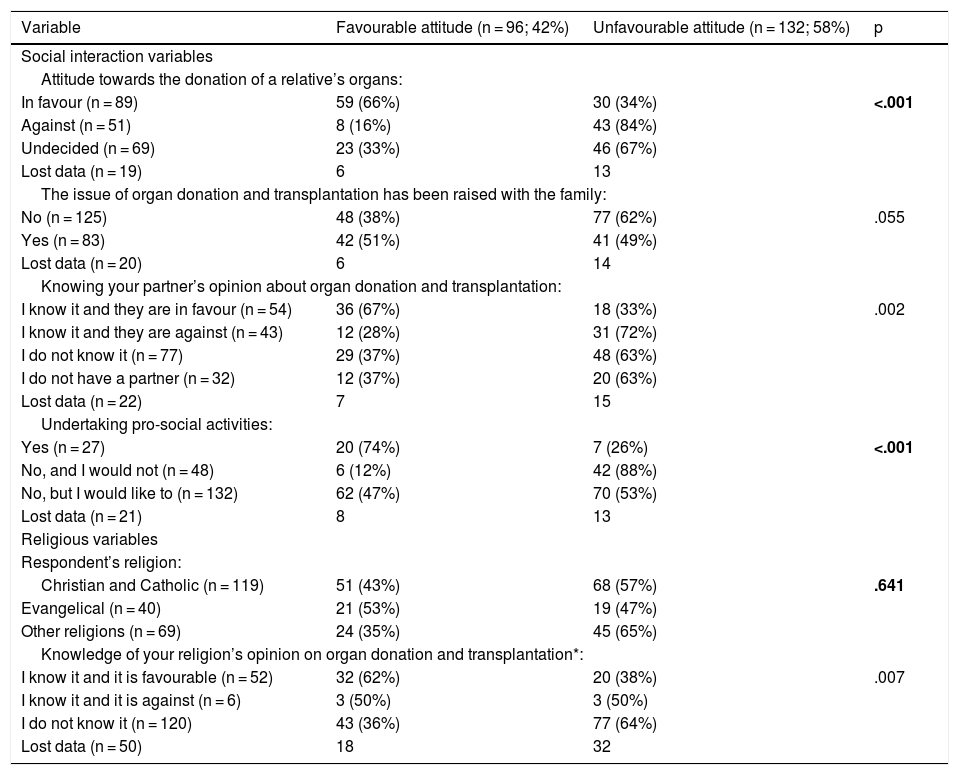

Social interaction variablesThe respondents in favour of organ donation from a deceased relative were more in favour of donation of their own organs (66%) than those who were not (16%) and those who were undecided (33%) (p < .001).

The respondents who had previously discussed the issue of organ donation and transplantation with their family were not found to have a more favourable attitude (p = .055). In contrast, it was associated with the attitude of the partner towards donation. Thus, when the partner was in favour and the respondent knew about it, 67% of respondents were in favour compared to only 28% when the partner was against it (p = .002; Table 3).

Social interaction variables and religious variables associated with attitudes towards organ donation after death among the Roma population.

| Variable | Favourable attitude (n = 96; 42%) | Unfavourable attitude (n = 132; 58%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social interaction variables | |||

| Attitude towards the donation of a relative’s organs: | |||

| In favour (n = 89) | 59 (66%) | 30 (34%) | <.001 |

| Against (n = 51) | 8 (16%) | 43 (84%) | |

| Undecided (n = 69) | 23 (33%) | 46 (67%) | |

| Lost data (n = 19) | 6 | 13 | |

| The issue of organ donation and transplantation has been raised with the family: | |||

| No (n = 125) | 48 (38%) | 77 (62%) | .055 |

| Yes (n = 83) | 42 (51%) | 41 (49%) | |

| Lost data (n = 20) | 6 | 14 | |

| Knowing your partner’s opinion about organ donation and transplantation: | |||

| I know it and they are in favour (n = 54) | 36 (67%) | 18 (33%) | .002 |

| I know it and they are against (n = 43) | 12 (28%) | 31 (72%) | |

| I do not know it (n = 77) | 29 (37%) | 48 (63%) | |

| I do not have a partner (n = 32) | 12 (37%) | 20 (63%) | |

| Lost data (n = 22) | 7 | 15 | |

| Undertaking pro-social activities: | |||

| Yes (n = 27) | 20 (74%) | 7 (26%) | <.001 |

| No, and I would not (n = 48) | 6 (12%) | 42 (88%) | |

| No, but I would like to (n = 132) | 62 (47%) | 70 (53%) | |

| Lost data (n = 21) | 8 | 13 | |

| Religious variables | |||

| Respondent’s religion: | |||

| Christian and Catholic (n = 119) | 51 (43%) | 68 (57%) | .641 |

| Evangelical (n = 40) | 21 (53%) | 19 (47%) | |

| Other religions (n = 69) | 24 (35%) | 45 (65%) | |

| Knowledge of your religion’s opinion on organ donation and transplantation*: | |||

| I know it and it is favourable (n = 52) | 32 (62%) | 20 (38%) | .007 |

| I know it and it is against (n = 6) | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | |

| I do not know it (n = 120) | 43 (36%) | 77 (64%) | |

| Lost data (n = 50) | 18 | 32 | |

In bold: statistically significant values.

With respect to religion, no relationship was found between attitude and the religion of the respondent (p = .641). Of those who were religious, knowing that their church is in favour of organ donation and transplantation was associated with a more favourable attitude than if they did not know this (62% versus 36%; p = 0.007; Table 3).

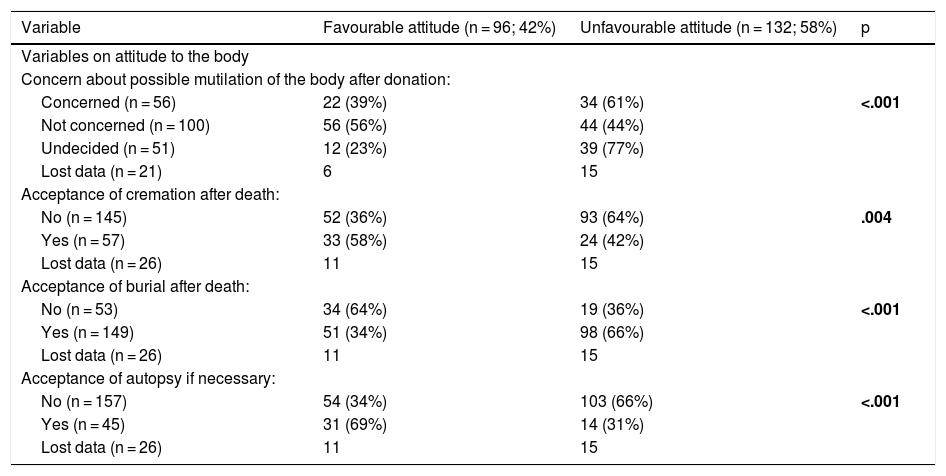

Variables on attitudes towards the bodyThere is a close relationship between the attitude towards the handling of the corpse and the attitude towards organ donation. Fear of mutilation after donation or doubts in this regard make the attitude towards donation worse than among those not reporting a fear of mutilation (39% and 23% versus 56%; p < .001; Table 4).

Variables on attitude towards the body associated with attitude towards organ donation after death among the Roma population.

| Variable | Favourable attitude (n = 96; 42%) | Unfavourable attitude (n = 132; 58%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables on attitude to the body | |||

| Concern about possible mutilation of the body after donation: | |||

| Concerned (n = 56) | 22 (39%) | 34 (61%) | <.001 |

| Not concerned (n = 100) | 56 (56%) | 44 (44%) | |

| Undecided (n = 51) | 12 (23%) | 39 (77%) | |

| Lost data (n = 21) | 6 | 15 | |

| Acceptance of cremation after death: | |||

| No (n = 145) | 52 (36%) | 93 (64%) | .004 |

| Yes (n = 57) | 33 (58%) | 24 (42%) | |

| Lost data (n = 26) | 11 | 15 | |

| Acceptance of burial after death: | |||

| No (n = 53) | 34 (64%) | 19 (36%) | <.001 |

| Yes (n = 149) | 51 (34%) | 98 (66%) | |

| Lost data (n = 26) | 11 | 15 | |

| Acceptance of autopsy if necessary: | |||

| No (n = 157) | 54 (34%) | 103 (66%) | <.001 |

| Yes (n = 45) | 31 (69%) | 14 (31%) | |

| Lost data (n = 26) | 11 | 15 | |

In bold: statistically significant values.

In this sense, those who would accept cremation of the body after death are more in favour of organ donation than those who would not (56% versus 36%; p = .004). However, it should be noted that only 28% (n = 57) would accept cremation. Similarly, those who prefer options other than burial after death have a more favourable attitude (64% versus 34%; p < .001). Finally, the attitude is more favourable among those who would accept an autopsy after death, if necessary (69% versus 34%; p < .001), as shown in Table 4. However, it should be noted that only 20% (n = 45) would accept an autopsy after death.

DiscussionThe low rates of organ donation among the Roma population cannot alone be explained by aspects of a population with a degree of social or health marginalisation.20–22 Other ethnic social or immigrant groups do not have such low rates of donation or such negative attitudes.3–6,23 This is possibly due to sociocultural factors that are deeply rooted in this social group and condition their attitude.

In this sense, the approach to death and bereavement is very characteristic of the Roma population.7–10 The Roma population is very respectful towards the deceased, and reject manipulation of the corpse. They usually reject autopsy or any other manipulation, including the removal of organs. This is irrespective of the health system and access to health services.24 However, the Roma population does accept organ transplants without problems should they need them.

This cultural and social approach to the process of death and mourning largely explains the lack of studies on organ donation and transplantation. This situation is conditioned by this ancestral fear, which means that Roma people do not even want to talk about the subject. Thus, the first attempts to approach this population to assess their attitude towards organ donation were a failure11 and data were only obtained from a highly aware subgroup of the Roma population, such as those with a university education.12

This situation is very important when analysing the results. Because for years now, our group has indicated the need to carry out controlled, stratified, population-based psychosocial studies in which the degree of compliance is fundamental.25 This is extreme and obvious. Therefore, from the start of the project, after the pilot study failed,11 a fundamental objective was to establish the reasons why the questionnaire was not completed. Especially in a project such as this, where more than 80% of the selected sample refused to participate in the study. This leads to a very evident positive selection bias towards cases in favour of donation, and therefore, exclusive analysis of the questionnaires obtained will give a distorted view of reality, as has already been seen in other studies.25 In this project, analysis of those who completed the questionnaire shows 42% of the population in favour of donation. This situation would not explain the real situation seen in the Transplant Coordination Offices, where organ donation from this social group is exceptional. Therefore, one of the objectives of this project was to determine why the questionnaire was not completed. It was found that 98% of those who refused to complete the questionnaire did so out of fear and refusal to talk about death and donation after death. This implies that this percentage of the sample has an unfavourable attitude towards organ donation after death, and therefore it can be concluded that only 7.8% would be in favour of organ donation after death. This percentage is the lowest described in the literature in favour of organ donation3–6,23 and reasonably explains the low donation rates of this social group.

Therefore, the psychosocial profile described for this social group, although it can help to determine the Roma population group that are most aware about donation (university educated, previous experience with donation and transplantation, etc.), is not useful for designing campaigns to promote organ donation in this population. The approach to this population to improve their attitude towards organ donation is complex, as it involves deep-rooted cultural aspects and changes in habits and rituals linked to the funeral and the mourning process.

In conclusion, we can say that most of the Roma population rejects raising the issue of death and organ donation after death, and this is deeply rooted and difficult to address. These findings explain why current campaigns to promote organ donation are not effective in this population group.

Ethics committeeThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee. Code: CE012116.

Funding for the studyThe study required no specific funding.

Availability of data and materialsThe Project database has not been deposited in a database repository. But the data are available on request to the corresponding author (Dr Ríos).

Authorship- 1)

Design: Ríos A.

- 2)

Substantial data acquisition: Ríos A, López-Gómez S, Belmonte J, López-Navas A, Ayala-García MA, Balaguer A.

- 3)

Data analysis and interpretation: Ríos A, López-Navas A, Ramírez P, Belmonte J.

- 4)

Design and preparation of the article: Ríos A, López Navas A, Belmonte J.

- 5)

Critical revision of the article and intellectual contribution: Ríos A, López-Navas A, Gutiérrez PR, Ramírez P.

- 6)

Statistical analysis: Ríos A, López-Navas A, Ruiz-Merino G.

- 7)

Securing financial and material funding to undertake the Project: Ríos A.

- 8)

Supervision: Ríos A, Gutiérrez PR, Belmonte J, López-Gomez S, Ramírez P, López Navas AI.

- 9)

Final approval of the version for publication: Ríos A, López-Gómez S, Belmonte J, Balaguer A, Gutiérrez PR, López-Navas A, Ayala-García MA, Ramírez P.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare

This study would not have been possible with the collaboration and support of the Roma associations that have been involved in the implementation and development of the project.

We would also like to thank the large number of collaborators who contributed to the fieldwork of the study and whose support was very necessary to undertake this project.