Flexible endoscopy (FE) plays a major role in the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disease. Although its intraoperative use has spread over the years, its use by surgeons is still limited in our setting. FE training opportunities are different among many institutions, specialties, and countries.

Intraoperative endoscopy (IOE) presents peculiarities that increase its complexity compared to standard FE. IOE has a positive impact on surgical results, due to increased safety and quality, as well as a reduction in the complications. Due to its innumerable advantages, its intraoperative use by surgeons is currently a current project in many countries and is part of the near future in others because of the creation of better structured training projects.

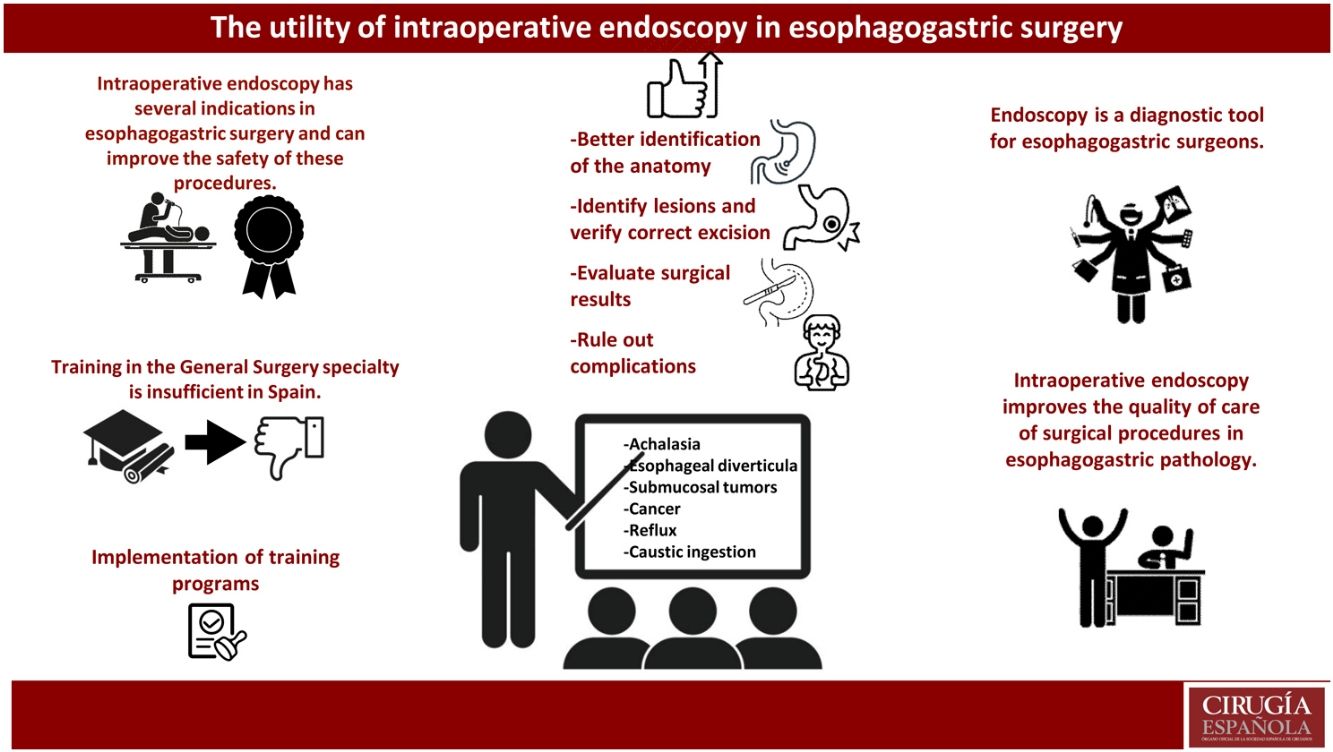

This manuscript reviews and updates the indications and uses of intraoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in esophagogastric surgery.

La endoscopia flexible (EF) es un procedimiento de gran utilidad para el manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico de lesiones del tracto digestivo superior. A pesar de que su uso intraoperatorio se ha extendido con el paso de los años, su empleo por parte de cirujanos es aún limitado en nuestro medio. Las oportunidades de capacitación en EF varían ampliamente entre instituciones, especialidades y países.

La endoscopia intraoperatoria (EIO) presenta ciertas peculiaridades que aumentan su complejidad respecto a la EF estándar. Su realización repercute positivamente en los resultados quirúrgicos aportándoles seguridad y calidad así como disminución de las complicaciones asociadas a estas técnicas. Debido a sus innumerables ventajas, su uso intraoperatorio por parte de cirujanos es actualmente un proyecto vigente en muchos países y forma parte de un futuro próximo en otros, extendiéndose su uso dentro de la especialidad de Cirugía General gracias a la creación de proyectos de formación mejor estructurados.

En este manuscrito se realiza una revisión y puesta al día de las indicaciones y utilidades de la endoscopia digestiva alta intraoperatoria en la cirugía esofagogástrica.

Over the years, surgery has become a less invasive and safer discipline, and tools have been developed to optimize results. In this context, intraoperative flexible endoscopy (FE) is a technique that provides clear benefits when used to assist surgery.

In 1880, the Austrian surgeon Mikulicz1 reported the use of a gastroscope to describe gastric cancer endoscopically. From these humble beginnings, flexible endoscopy has developed exponentially, and its use has spread to multiple procedures. In 2010 in Japan, peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) was described for the treatment of achalasia by the surgeon Haruhiro Inoue,2 and today a large percentage of early gastric cancers are treated by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR),3 endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) or the DEILO procedure recently described by Mochiki.4

Intraoperative endoscopy (IOE) may not only be very useful but essential to safely complete certain surgical procedures, even becoming an inseparable component of them. For instance, IOE can be used to establish resection limits, identify lesions that are difficult to view extraluminally, confirm the integrity of an anastomosis, or rule out intraoperative complications. The technique is currently relegated to use in certain emergency situations or for problem solving, and it is performed in most hospitals by specialized gastroenterologists.5

This manuscript reviews FE training in General Surgery and updates the indications and possible benefits of digestive endoscopy in esophagogastric surgery.

Intraoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopyUtility of IOEThe immediate availability of intraoperative endoscopy during the development of surgical procedures in the upper gastrointestinal tract contributes to improved safety by reducing operative times and potential complications associated with surgery.

A complete IOE examination includes inspection of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Experts recommend a minimum exploration time of 7 min. In this regard, one study has shown that endoscopists who spent more time for IOE detected a greater number of premalignant gastric lesions (OR 2.5), cancer, and lesions with dysplasia (OR 3.42).6 During its intraoperative use, the technique can be more precisely directed, avoiding areas already explored in previous endoscopies and instead focusing on the specific pathology and surgical procedure.

The advantages of and general indications for the use of IOE in esophagogastric surgery include:

- -

The ability to identify intraluminal anatomy and relate it to extraluminal findings during surgery.

- -

Adequate calibration of the organ before the excision of lesions or creation of anastomoses.

- -

Ability to identify lesions in situ and verify complete resections with safety margins, thereby avoiding unnecessarily extensive resections.

- -

Intraluminal evaluation of the surgical results once the procedure is finished.

- -

Ability to assess the anastomosis for leaks and rule out bleeding as well as possible iatrogenic injuries.

To perform IOE, certain factors must be considered that differentiate it from the standard procedure.

IOE is performed on a patient under orotracheal intubation, so the degree of difficulty may be greater. Endotracheal tubes must be secured to the right side of the mouth to perform the examination, and a bite block is placed in conjunction with the airway device.7 The patient position will vary, and in some cases the patient will be in a supine, lateral, prone or semi-prone position, which sometimes makes access difficult. The placement of the tower and the equipment necessary to perform the endoscopy in the operating room must be adapted to the spatial arrangement, without overlooking the ergonomic needs of the specialist performing the IOE. In addition, the insufflation of excess air/CO2 can hinder the surgical approach by distending the stomach and small intestine. In addition, the lumen of the laparoscope can sometimes hinder or reduce the quality of the endoscopic vision.

Most common scenarios for its useAchalasia surgeryIn the surgical treatment of achalasia, IOE is used to evaluate the quality and extension of the myotomy,8 allowing its length to be extended both cranially towards the esophagus and distally towards the stomach. It is also used to evaluate circular muscle fibers that have not been divided, which are more noticeable when the esophagus is distended and transilluminated with the endoscope (Fig. 1) (Video 1).

In addition, IOE makes it possible to identify mucosal perforations that were overlooked during the performance of the myotomy9 so that these can be sutured. As a result, the safety of the procedure is improved.

In the same way, IOE can be used to evaluate the state of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) before and after performing the recommended fundoplication in these patients to avoid gastroesophageal reflux, and this marks the difference in functional results compared to myotomy performed endoscopically (POEM). In comparative studies, the POEM technique and laparoscopic Heller myotomy present similar results in terms of efficacy, complications, and need for analgesia, reducing the procedure time in the case of POEM.10

In recent years, the incorporation of intraoperative manometry using the endoFLIP device makes it possible to assess the status of the myotomy and the esophagogastric junction. However, well-designed studies with a larger number of cases and evaluation of long-term results are necessary to determine its true performance.11,12

Surgery for esophageal diverticulaThe use of IOE during esophageal diverticula surgery is very useful to accurately diagnose the location of the diverticulum as it defines the beginning of the neck and assists in its identification by means of insufflation and transillumination with the endoscope (Video 2). In addition to ruling out other possible lesions or associated alterations, IOE can detect food debris that may be retained in the fundus and diverticular neck, which can be cleaned out for easier diverticular neck division in tissue without debris that could interfere with stapling. In addition, it makes it possible to evaluate the complete resection of the diverticulum and verify that the esophageal lumen is not reduced after its division (Fig. 2), an important point in different types of surgeries that involve partial resections.13

As in achalasia surgery, IOE in these patients makes it possible to assess the extent of the myotomy up to the neck of the diverticulum and rule out possible mucosal perforations.14

In addition, endoscopy is currently used for therapeutic purposes in the management of Zenker’s diverticulum, dividing the muscular septum with an endostapler15 or bipolar sealer.16 In selected cases, it has shown satisfactory results, with a symptom resolution rate close to 90%.17 POEM has also been described as a treatment for middle-third esophageal diverticula, although the publications are limited to short case series.18,19

Surgery for submucosal tumorsSubmucosal esophagogastric tumors are rare and represent less than 10% of all tumors located in this structure, while leiomyomas are the most frequent.20

IOE has been used to intraoperatively identify the tumor (Fig. 3A), facilitate its enucleation, and evaluate the integrity of the mucosa after resection (Video 3).21,22

Some groups describe the use and endoscopic placement of a balloon that, after endoluminal inflation, makes it easier for the tumor to protrude outwards, assisting in its safe thoracoscopic enucleation.23

As in other types of esophageal lesions, an exclusively endoscopic approach has been described to resect the tumor by injecting a substance into the esophageal mucosa to separate the tumor from the submucosa for later excision.24

In the case of GIST tumors, the intraoperative endoscopic approach is very useful to establish the exact location of the lesion (Fig. 3B). In selected cases, it can be used to perform combined transgastric or purely endoscopic resections, especially in locations that would require more aggressive surgery like the esophagogastric junction (Fig. 4A) or the antropyloric region.

Endoscopic resection (ER) includes different modalities, such as endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), endoscopic submucosal excavation (ESE), endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), and submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection (STER).25 ESD is considered an effective technique for GIST; however, for tumors originating in the deep muscularis propria, ESE and EFTR can be used.26 STER is generally used to treat GIST of the cardia as it protects the integrity of the mucosa.27 It is sometimes difficult to determine the limits of the tumor using laparoscopy, and in these cases a technique combining laparoscopic gastric resection with intraluminal endoscopy (laparoscopic and endoscopic cooperative surgery, or LECS) is recommended28 (Fig. 4B and 4C).

Cancer surgeryIOE is very useful for identifying tumor lesions that are not palpable or visible by thoracoscopy or laparoscopy and have not been marked previously (Fig. 3C).

In the same manner, it allows specialists to evaluate the endoluminal tumor extension, guaranteeing macroscopic tumor-free proximal and distal edges. In the case of adenocarcinomas of the distal esophagus that settle on Barrett’s esophagus, IOE helps identify the extension of the metaplasia so that areas of possible involvement outside the area of surgical resection are not left unresected.

In lesions located in the mucosa without lymph node involvement and without risk factors, endoscopic resection techniques have been described and are applied with satisfactory oncological results and a low rate of complications. The most widespread is ESD, with a complete local remission rate ranging from 80% to 99%29 and a disease-free survival rate ranging from 87% to 100%.30 Associated complications such as bleeding, perforation (0%–2%) and stenosis are rare, and their endoscopic management is generally successful.31

After the resective part of this type of surgery, it is necessary to proceed with the reconstruction of the digestive tract by creating anastomoses. With the use of IOE, this type of anastomosis can be safely evaluated, ruling out the existence of a defect or detecting an air leak when introducing the endoscope and submerging the anastomosis in saline (Fig. 5). Several studies have shown that IOE reduces the risk of postoperative leaks and is considered the best test to examine the anastomosis intraoperatively.32–35 The use of IOE to assess the integrity of the anastomosis in colon surgery is associated with fewer complications.36,37

(A) Endoscopic view of a side-to-side mechanical gastrojejunal anastomosis; (B) Endoscopic view of a mechanical end-to-side esophagojejunal anastomosis with CEEA of 25 mm; (C) Endoscopic view of a mechanical end-to-side esophagogastric anastomosis with CEEA of 25 mm (in the cervical region).

In addition, the diameter of the anastomosis can be evaluated, ruling out possible stenosis as well as possible hemorrhagic foci along the staple line.34,38

In the case of esophagectomies, IOE is also used to evaluate the mucosa of the tissue used for reconstruction, ruling out the presence of areas of ischemia or mucosal lesions, bleeding, or perforation both along the division line for the creation of the gastroplasty, as well as in the pyloroplasty area if used. In addition, IOE makes it possible to rule out the presence of possible torsion of the graft caused during the pull up to the thorax or neck or kinking in redundant tissue.

Esophagogastric reflux surgeryIn this type of surgery, IOE makes it possible to detect possible complications secondary to reflux or associated anatomical alterations, such as hiatal hernia.

Once the surgical dissection has been performed, the IOE allows us to verify the adequate esophageal length (ruling out a short esophagus), the presence of sufficient abdominal esophagus, and the exact location of the esophagogastric junction (by identifying the squamocolumnar junction) in order to perform the fundoplication in a correct position. Once this is completed, IOE is used to assess its competence (degree to which the fundoplication embraces the endoscope when performing retrovision) and to rule out high pressure (resistance when passing the endoscope through the esophagogastric junction), which may compromise postoperative results (Fig. 6) (Video 4).

With the intraoperative use of IOE, some series have reported corrections being made in 28% of procedures, while the type of fundoplication was changed in 2.5% to avoid stenosis or angulations.39

Where IOE acquires greater importance is in revision surgery, where it is used to diagnose the problem that requires reintervention, identify the esophageal lumen by transillumination during adhesiolysis, and evaluate the quality of the new fundoplication, ruling out possible perforations or mucosal injuries.

Surgery for caustic lesionsEsophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the best test to evaluate the mucosa of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum, and its role is crucial in the management of patients with caustic ingestion injuries. In these patients, mucosal alterations can be detected 6 h after ingestion. However, 48 h or more after ingestion, this test must be performed with caution due to the risk of perforation. The general recommendation is to perform the test early on because some 30% of patients will have no esophageal injury after caustic ingestion and can be discharged quickly.40,41 The test is not recommended in cases of airway obstruction or severe respiratory distress, severe lesions in the hypopharynx, perforation of the hollow viscus, or hemodynamic instability.

Despite the advantages that computed tomography (CT) scans offer in the diagnosis of possible complications and necrosis of the digestive tract,42 the use of IOE assists in situ evaluation of the location and severity of the lesions for decision-making regarding the extension and type of surgical resection needed.

During the follow-up of these patients, EGD can help assess the appearance of new lesions, stenosis or even neoplasms.

Endoscopic treatment of stenosis secondary to the ingestion of caustic substances is generally performed 3 weeks after ingestion and should not be delayed beyond 8 weeks, when scar tissue is fully formed and the results of endoscopic dilation are usually unsatisfactory.43 Despite the wide variety of dilators, all seem to have a comparable success rate (25%–95%), depending on the severity of the stenosies,44,45 and a perforation rate of 0.1%–0.4%.46

In the case of refractory strictures, other techniques have been used, such as electrocautery,47 intralesional steroid injection,48 mitomycin-C injection,49 and esophageal stenting (success rate: 33%, migration rate: 40%).50

Possible complications associated with IOEDespite the described advantages of IOE, this procedure is not exempt from possible complications, such as bleeding, perforation, etc. To avoid them, the surgeon and operating room staff must be adequately trained and educated in the use, care, maintenance, decontamination, and solution of possible equipment problems and commonly used tools.51

Employment, learning and accreditationFlexible endoscopy (FE) training opportunities vary widely between institutions, specialties and countries. Although FE training is included in mandatory surgical residency training in countries such as North America, Australia and parts of Asia, surgeons in other parts of the world do not have access to FE practice during their training or later over the course of their professional career.52–54

Current situation in SpainAt most hospitals in our country, FE is conducted by gastroenterologists specialized in endoscopy, and there are few medical centers where surgeons are responsible for performing this examination for diagnostic purposes.

Currently, the training programs for resident physicians in General and Digestive System surgery provide insufficient training in FE.

Due to the advantages offered by FE, access to training, accreditation and practical experience should be strongly endorsed by scientific and surgical societies. Steps toward a more uniform and appropriate training experience should include addressing current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) policies, using available resources efficiently (including simulators), and instituting a standardized and validated training curriculum for endoscopy that incorporates the recommendations of the surgical and gastrointestinal medical societies.55

In an attempt to expand its use and implement this technique in our operating rooms, the Spanish Association of Surgeons has designed a training program in intraoperative endoscopy for digestive surgeons. This program consists of 5 phases and was launched in December 2020. In a few years, we will be able to evaluate the results of this initiative and the degree of implementation of this procedure in our work routine.

Current situation in other countriesIn Canada, endoscopic training is part of the core curriculum of general surgery residency, and general surgeons perform approximately 50% of all endoscopic procedures.56 Despite this, in a survey conducted on endoscopy training, 47% of surgeons reported that current training in endoscopy is inadequate, and 39% of surgical residents felt unprepared to perform endoscopy due to deficient training.54,57

In America, general surgeons perform both diagnostic and non-intraoperative therapeutic endoscopies. The American Board of Surgery (ABS) recognized the need to include endoscopy training in the General Surgery residency program, so in 1985 the Board recommended a minimum of 29 cases performed by residents during their training. This was later increased to 35 upper GI endoscopies (EGD) and 50 colonoscopies. The Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) developed the Fundamentals of Endoscopic Surgery (FES) program, which was launched in 2010 to standardize and evaluate endoscopic training.58

In the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS), FE training is part of the General Surgeons’s curriculum, although it is not comparable in all countries. In 2014, the Institute for Research against Digestive Cancer (IRCAD) participated in the development of a one-year university diploma program using advanced education methods to offer both surgeons and gastroenterologists high-quality training in flexible endoscopy. The curriculum combines online learning, clinical practice, and clinical follow-up.59 In the United Kingdom, the EGD certification program is common for surgeons and gastroenterologists, which requires 200 procedures to obtain competence and before independent practice; access to certification is by through DOPS (Direct Observation of Procedural Skills).60

In many Asian countries, training in endoscopy is part of residency training programs.61 However, there is still a lack of a standardized strategy for teaching,62 and general physicians perform most endoscopies.

ConclusionIOE is a technique that provides significant advantages that improve the safety of surgical procedures in esophagogastric pathology and should be implemented by surgeons in their surgical activity.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.