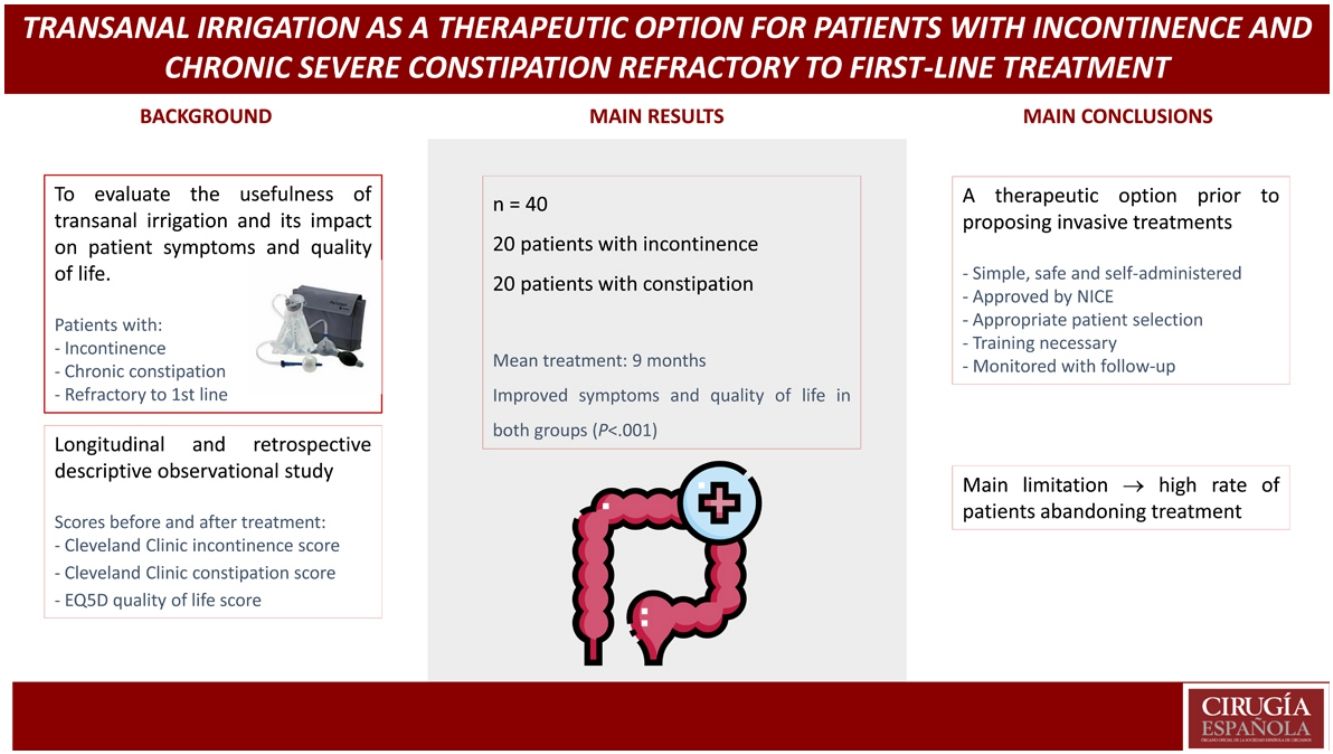

The aim is to evaluate the utility of transanal irrigation such as treatment of incontinence and severe chronic constipation which is refractory to first-line therapy, and to assess its impact into the symptomatology and quality of life.

MethodsObservational retrospective study of patients with incontinence and chronic constipation that had initiated transanal irrigation in two hospitals of the region. We collect sociodemographic variables, comorbidity, previous treatments, tests, parameters and incidences during the irrigation, and punctuation in the Cleveland Clinic Incontinence and Constipation Scores and EuroQol-5D Quality Of Life Scale before and after the treatment.

Results40 patients, 20 with incontinence and 20 with chronic constipation. After an average period of 9 months of treatment, in 14 patients with incontinence we have observed a mean clinical improvement of 7,45 points before-after treatment measured with Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score, and a mean improvement of 23 points in their quality of life before-after treatment measured with EQ5D Scale (P < .001); and in 16 patients with constipation a mean clinical improvement of 7,6 points before-after treatment measured with Cleveland Clinic Constipation Score, and a mean improvement of 31,5 points in their quality of life before-after treatment measured with EQ5D Scale (P < .001).

ConclusionsTransanal irrigation is an effective therapy for patients with incontinence and chronic constipation that are refractory to first-line therapies. It’s an easy, self-administered and safe procedure. When the patient learns how to use it, the symptomatology and quality of life are improved.

El objetivo es evaluar la utilidad de la irrigación transanal como tratamiento de la incontinencia y estreñimiento crónico severo refractario a primera línea terapéutica, y valorar su impacto en la sintomatología y calidad de vida.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo descriptivo de pacientes con incontinencia y estreñimiento crónico que han iniciado irrigación transanal en dos hospitales de la región. Se recogen variables sociodemográficas, comorbilidades, tratamientos previos, pruebas realizadas, parámetros e incidencias durante la irrigación, puntuación en las escalas de gravedad de incontinencia y estreñimiento de la Cleveland Clinic y calidad de vida EuroQol-5D antes y después del tratamiento.

Resultados40 pacientes, 20 con incontinencia y 20 con estreñimiento crónico. Tras una media de 9 meses de tratamiento, en 14 pacientes con incontinencia hemos objetivado una media de mejoría de 7,45 puntos pre-post tratamiento en la escala de gravedad de incontinencia de la Cleveland Clinic, y una media de mejoría en la calidad de vida de 23 puntos pre-post tratamiento en la escala EQ5D (p < 0.001); y en 16 pacientes con estreñimiento una media de mejoría de 7,6 puntos pre-post tratamiento en la escala de gravedad de estreñimiento de la Cleveland Clinic, y una media de mejoría en la calidad de vida de 31,5 puntos pre-post tratamiento en la escala EQ5D (p < 0.001).

ConclusionesLa irrigación transanal es una terapia efectiva para pacientes con incontinencia y estreñimiento crónico no respondedores a primera línea terapéutica. Es sencilla, autoadministrable y segura. Cuando el paciente aprende a emplearla, mejora su sintomatología y calidad de vida.

Incontinence and chronic constipation are relatively common conditions in the population that have a significant impact on quality of life, with a prevalence of approximately 15% each, although this rate varies depending on age, gender, socioeconomic status or associated comorbidities.1

Conservative measures can be used to manage these conditions, including changes in hygienic and dietary habits, biofeedback and pharmacological treatments. More invasive therapies include neuromodulation of nerve roots or surgery to create a stoma.

Another therapeutic option is transanal irrigation, which has been approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for patients with neurogenic and functional intestinal dysfunction, such as chronic constipation and incontinence, who require an alternative strategy to conservative treatment.2 It should be considered after appropriate use of conservative measures, including biofeedback, when these have not been effective.3

In this study, we have evaluated the usefulness of transanal irrigation as a treatment for incontinence and severe chronic constipation refractory to first-line therapy, as well as its impact on patient quality of life.

MethodsWe conducted a descriptive, longitudinal and retrospective, observational study of patients diagnosed with incontinence of diverse etiology and severe chronic constipation refractory to first-line therapies, who had initiated transanal irrigation in 2 second-level hospitals. We did not calculate a sample size but instead included all patients who met the criteria and agreed to start treatment between December 2019 and June 2021. We did not include patients with spinal cord injury or with anterior resection syndrome, as most present a combination of symptoms that could make analysis difficult. Patients treated simultaneously with posterior tibial and/or sacral neuromodulation were also not included.

We have collected data for the following: sociodemographic and clinical variables (age, sex and comorbidities); history of anorectal surgery for benign pathology or obstetric injuries; degree of incontinence and etiology of constipation; dietary modifications and habits (physical exercise and routine bowel movement); pharmacological therapy (astringents, pear enemas or colon lavages, laxatives, digital disimpaction); and whether they have undergone biofeedback or pelvic floor rehabilitation.

All patients included in the study had a previous complete colonoscopy to rule out organicity.

Patients with incontinence underwent ultrasound and anorectal manometry. Those with constipation were studied with manometry, colonic transit time and defecography, depending on the type of constipation.

Data were collected about the characteristics of the transanal irrigation, time from the start of treatment, volume used, periodicity, incidents with its use, and abandonment of therapy. Finally, the Cleveland Clinic incontinence and constipation severity scale scores4,5 and the EuroQol-5D (EQD5) score6 were recorded before and after the start of treatment.

The characteristics of both groups are described, and irrigation in each group was evaluated, with no attempt made at comparing the two.

Once the colorectal surgeon indicated irrigation as well as the type of catheter to be used and the initial volume, the stoma nurse conducted an initial interview and recorded the Cleveland Clinic and EQ5D scores. The patient (or a family member) was then trained in irrigation with the Peristeen® irrigator system (Coloplast, Humlebaek, Denmark), watching a video that explained its use. In constipated patients, daily irrigation was initiated with volumes equal to or greater than 400 mL the first week. Subsequently, the volume and frequency of irrigation were adjusted according to the patient’s needs and management. In incontinent patients who had never used enemas or retrograde lavages, we started with volumes of 300 mL. We recommend using tap water as irrigating liquid, with a temperature between 36 °C and 38 °C, following the irrigation instructions provided by the system.3,7

We did not include data obtained from the defecation diaries due to the difficulty that we had in collecting them and their incompletion by patients.

In the second week, the first patient follow-up appointment was conducted by nursing staff to verify correct irrigation usage. The one-month follow-up evaluation was done by the Surgery Service to assess patient adaptation to treatment. The appointment after the second month was conducted by nursing staff, and subsequently by the Surgery Service after 3 and 6 months. At this last follow-up appointment, the corresponding Cleveland Clinic and EQD5 scores were again recorded.

After 8–12 weeks, if treatment was not satisfactory, we reassessed the case with the patient and/or caregiver to try to resolve any technical difficulties or complications with its use that may have arisen.

Statistical analysisFor the descriptive analysis of all variables, we calculated the number and percentage for qualitative variables, and minimum, maximum, mean and standard deviation value for quantitative variables, using the SPSS 25.0 statistical program for Windows.

For the analysis of the scores from the 3 scales used, and since the sample was small, we applied the Wilcoxon test for paired samples, obtaining scores before and after treatment. All tests with P < .05 were considered significant.

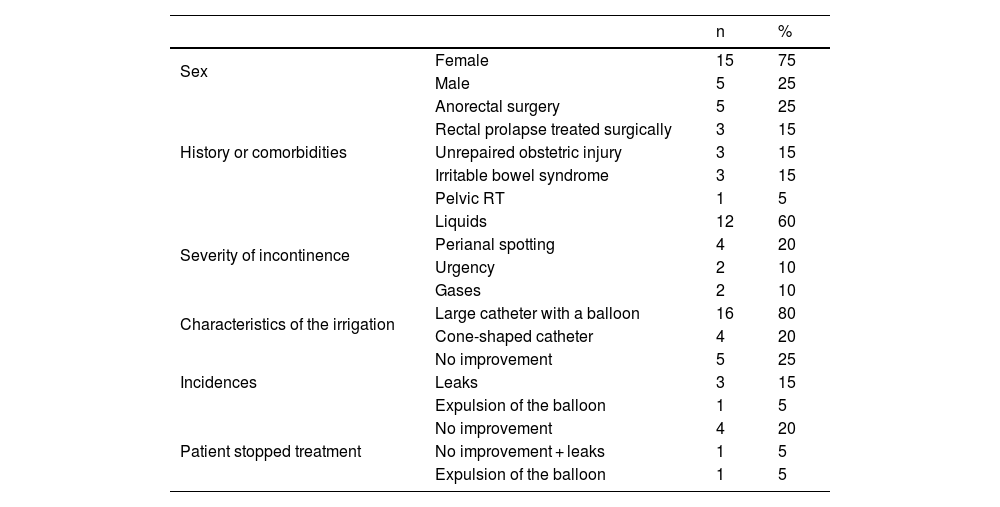

ResultsOur study included 20 patients with incontinence (15 women and 5 men), with a mean age of 55.5 years ± 11.6 (27–73). Five had a history of anorectal surgery (3 perianal fistulae and 2 hemorrhoids); 3 had undergone laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for rectal prolapse; 3 had unrepaired obstetric injuries; 3 had been diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome; and 1 had a history of pelvic radiotherapy for cervical neoplasm.

All patients had modified their hygienic-dietary habits, used astringent drugs such as loperamide, enemas or colon lavages, biofeedback, and pelvic floor rehabilitation (if pathological perineal descent was observed), with no improvement.

In terms of severity, 12 patients presented liquid incontinence, 4 perianal spotting, 2 urgency and 2 gas incontinence, both with irritable bowel syndrome. We included in the series the patients with spotting as it significantly impacts their quality of life, in addition to occasional associated gas leaks.

Endoanal ultrasound revealed a sphincter injury in 6 patients, 4 with a history of anal canal surgery (2 perianal fistulae and 2 hemorrhoids) and 2 with obstetric injuries.

Regarding irrigation, 16 patients used a large balloon catheter, while the remainder used a conical catheter. Mean volume was 600 mL (range: 400−900 mL), and the most frequently used frequency was every other day. During follow-up, 5 patients showed no improvement, 3 had leaks during irrigation and 1 experienced expulsion of the balloon associated with an obstetric sphincter injury greater than 180° who had rejected any surgical treatment option. There were no major complications during follow-up.

Mean duration of treatment was 9 months when the data were collected. Six patients stopped treatment: 5 due to lack of improvement (1 of them also leaked during irrigation), and 1 due to expulsion of the balloon. The main characteristics of these patients are described in Table 1.

Main characteristics of patients with incontinence.

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 15 | 75 |

| Male | 5 | 25 | |

| History or comorbidities | Anorectal surgery | 5 | 25 |

| Rectal prolapse treated surgically | 3 | 15 | |

| Unrepaired obstetric injury | 3 | 15 | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 3 | 15 | |

| Pelvic RT | 1 | 5 | |

| Severity of incontinence | Liquids | 12 | 60 |

| Perianal spotting | 4 | 20 | |

| Urgency | 2 | 10 | |

| Gases | 2 | 10 | |

| Characteristics of the irrigation | Large catheter with a balloon | 16 | 80 |

| Cone-shaped catheter | 4 | 20 | |

| Incidences | No improvement | 5 | 25 |

| Leaks | 3 | 15 | |

| Expulsion of the balloon | 1 | 5 | |

| Patient stopped treatment | No improvement | 4 | 20 |

| No improvement + leaks | 1 | 5 | |

| Expulsion of the balloon | 1 | 5 |

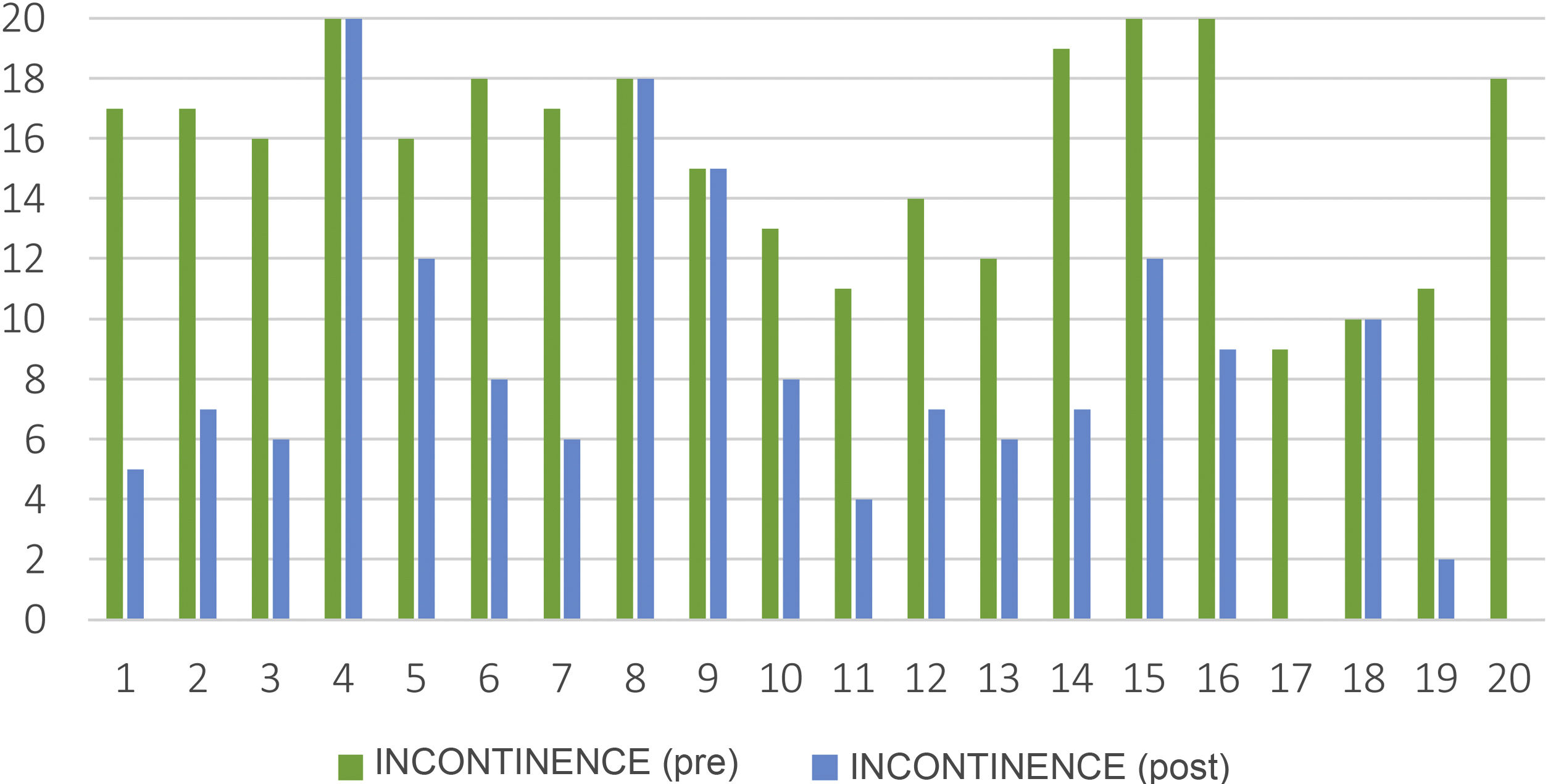

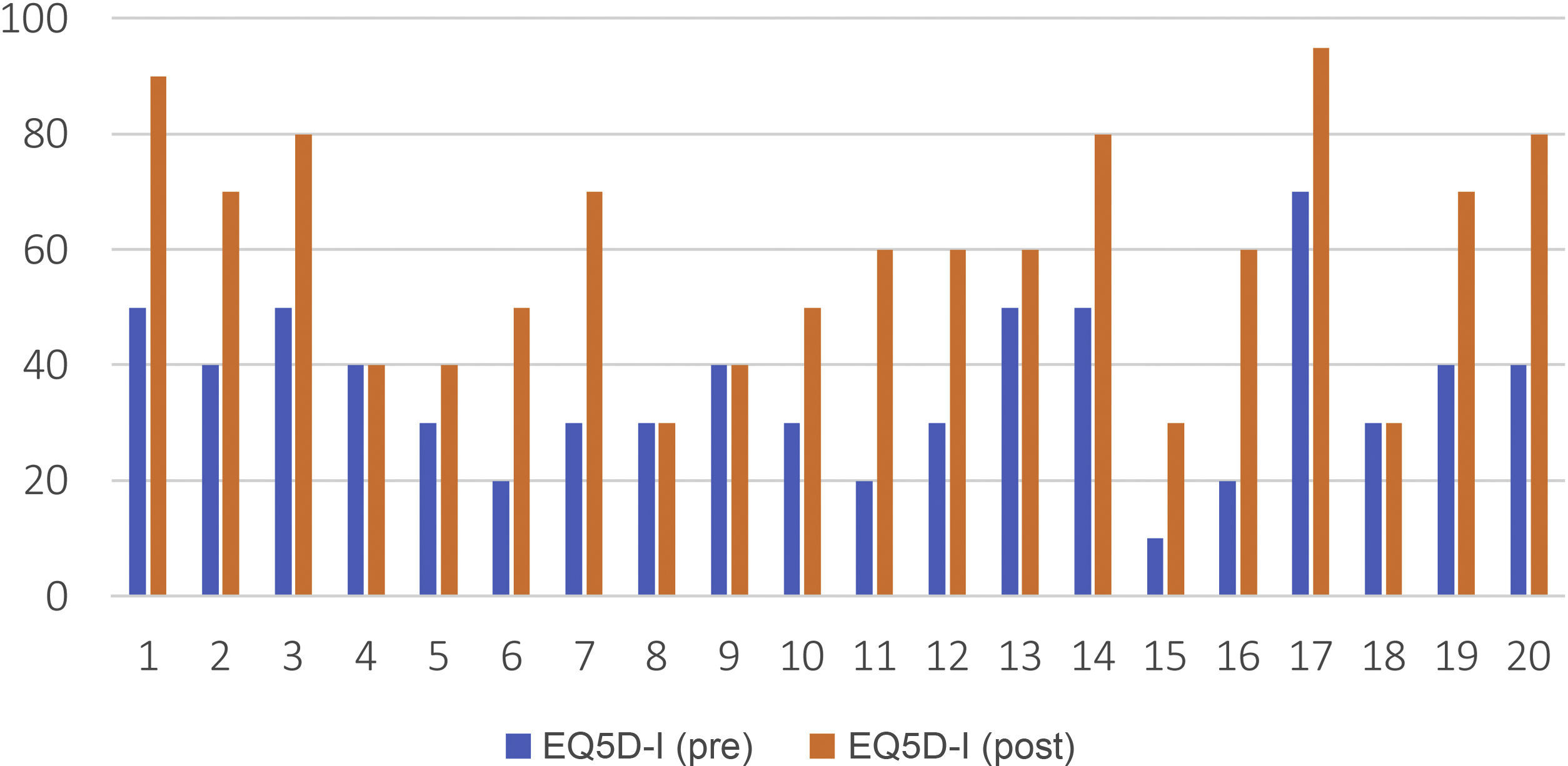

The 14 patients who continued treatment showed significant improvement on the Cleveland Clinic incontinence severity scale, with a mean pre-post treatment score of 7.45 points (15.55−8.10) (P < .001) (Fig. 1). The same was true for the EQ5D quality-of-life scale, with a mean pre-post treatment score of 23 points (36–59.25) (P < .001), as shown in Fig. 2.

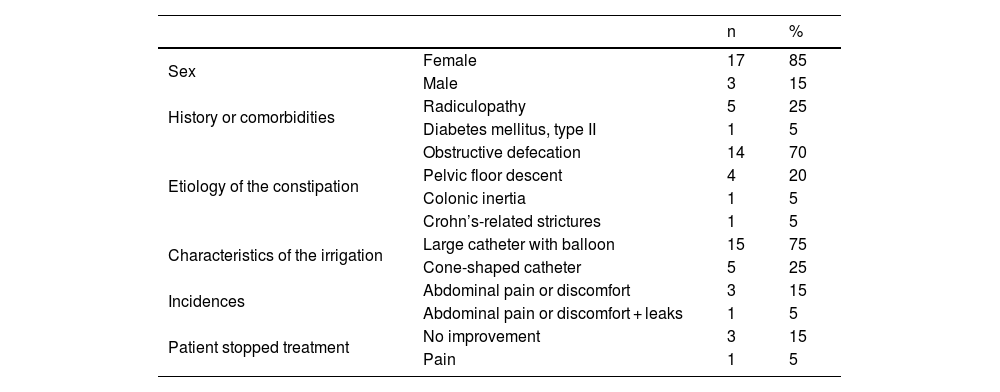

Our study also included 20 patients with chronic constipation (17 women and 3 men), with a mean age of 52.4 years ± 17.3 (22–77). Five patients presented associated radiculopathy (3 bilateral radiculopathy of L5-S1, one bilateral L2–L4 [this patient also presented symptoms of fluid incontinence but was assigned to the constipation group] and one with L5 anterior radicular injury), and another patient had type 2 diabetes mellitus.

All patients had modified their diet and habits, using oral laxatives such as lactulose, macrogols and (in 3 patients) prucalopride and linaclotide; 9 used enemas or micro-enemas; 2 colon lavages with a rectal bulb syringe or catheter and 1 digital disimpaction; and biofeedback, without improvement.

In terms of the type of constipation, 14 had symptoms of obstructive defecation, 4 pelvic floor descent, 1 colonic inertia, and 1 stricture of the anal canal due to Crohn's disease (inactive for more than 10 years).

We have the results of 13 anorectal manometries: 8 with defecatory dyssynergia and 5 with abnormal results in the balloon expulsion test.

Regarding irrigation, 15 patients used a large balloon catheter, the remainder a conical catheter, with a mean volume of 800 mL (400−1000 mL). The most common frequency of treatment was every 2 days. During follow-up, 4 patients reported abdominal pain, and one of them also had leaks during irrigation.

The mean duration of treatment was 9 months at the time of data collection. Four patients abandoned treatment: 3 due to lack of improvement and one due to pain. No other minor complications have been reported, and none of the patients have presented serious complications with the user of irrigation. The main characteristics of these patients are described in Table 2.

Main characteristics of patients with constipation.

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 17 | 85 |

| Male | 3 | 15 | |

| History or comorbidities | Radiculopathy | 5 | 25 |

| Diabetes mellitus, type II | 1 | 5 | |

| Etiology of the constipation | Obstructive defecation | 14 | 70 |

| Pelvic floor descent | 4 | 20 | |

| Colonic inertia | 1 | 5 | |

| Crohn’s-related strictures | 1 | 5 | |

| Characteristics of the irrigation | Large catheter with balloon | 15 | 75 |

| Cone-shaped catheter | 5 | 25 | |

| Incidences | Abdominal pain or discomfort | 3 | 15 |

| Abdominal pain or discomfort + leaks | 1 | 5 | |

| Patient stopped treatment | No improvement | 3 | 15 |

| Pain | 1 | 5 |

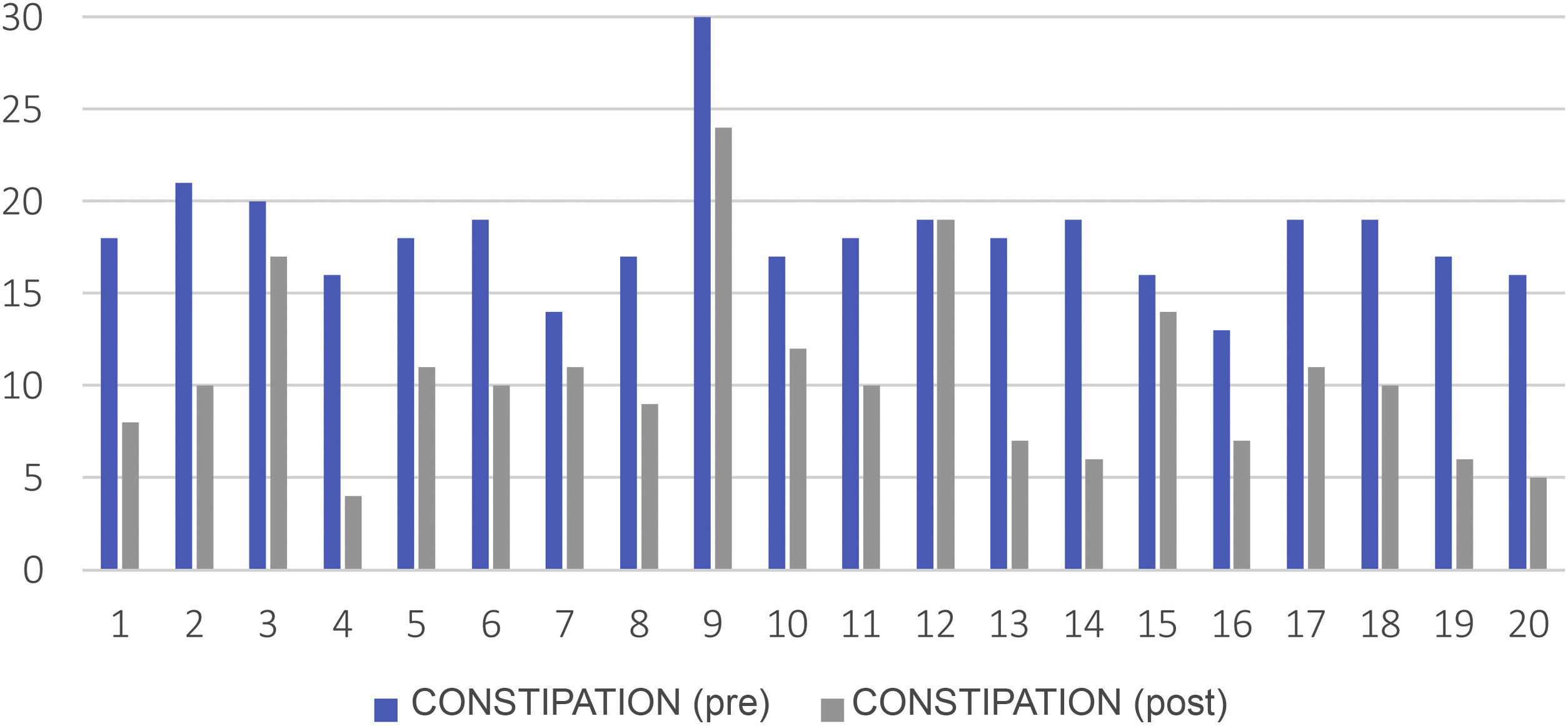

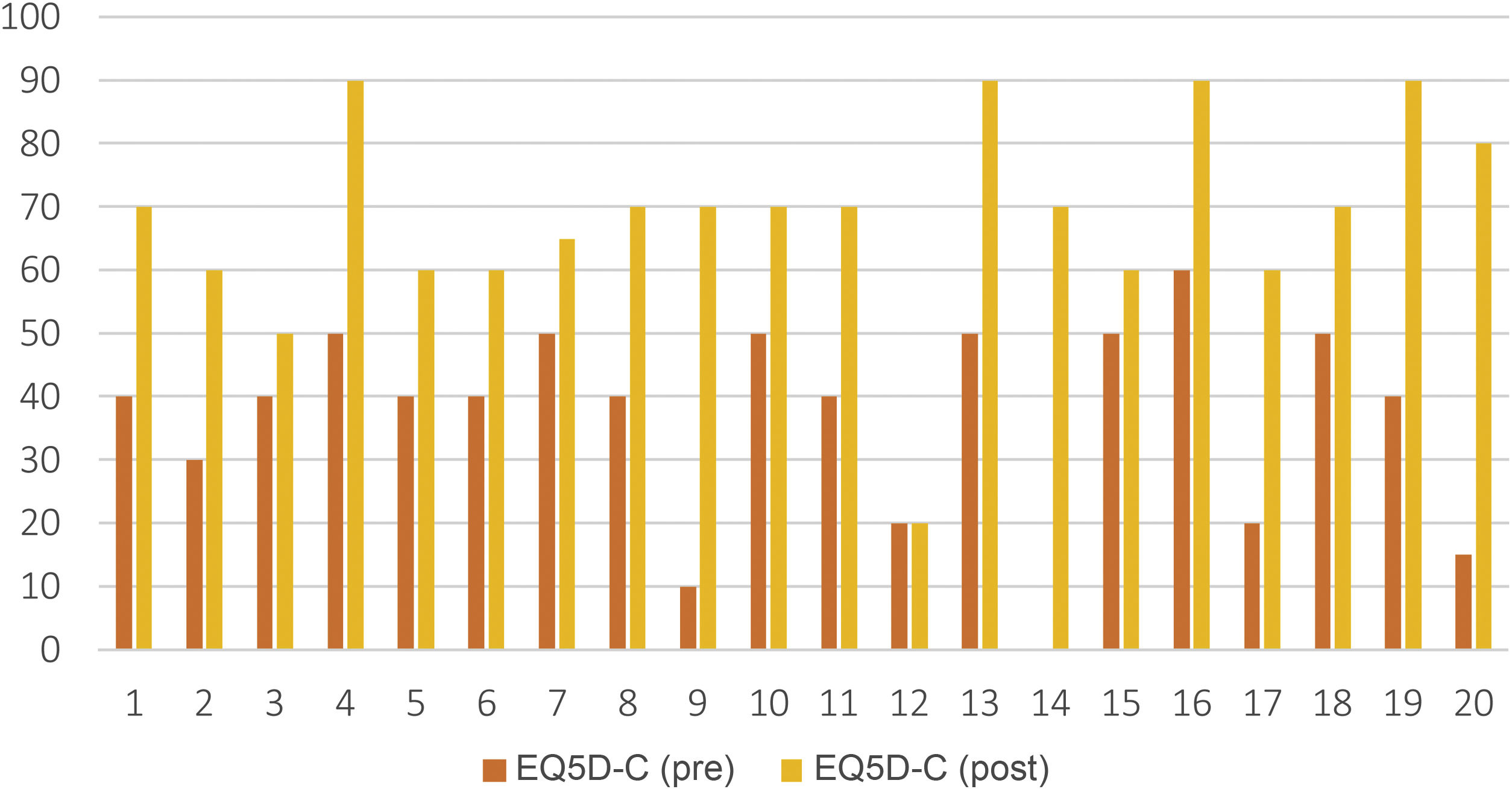

The 16 patients who continued treatment have significantly improved in the Cleveland Clinic Constipation Severity Scale score, with a mean pre-post treatment of 7.6 points (18.20−10.55) (P < .001), (Fig. 3); the same is true for the EQ5D quality-of-life scale, with a mean pre-post treatment score of 31.5 points (36.75–68.25) (P < .001), as seen in Fig. 4.

When conservative treatments for incontinence and chronic constipation fail, transanal irrigation is an intermediate therapeutic step. Its use has been increasing in recent years and has been shown to improve the symptoms and quality of life of these patients.2,8,9

It is an easy-to-learn, self-administered treatment that is well accepted by most patients. It is also a safe, low-cost procedure.10–12

In incontinence, irrigation provides regular bowel emptying so that stools do not reach the rectum for an average of 2 days,1,8 which improves bowel function.13 In constipation, it causes emptying of the rectum and distal colon, which stimulates intestinal motility and prevents fecal impaction.8,14,15

Irrigation has demonstrated very satisfactory results in spinal cord injuries and in anterior resection syndrome.8,10,12 The series by Enriquez-Navascues et al. compared it with neuromodulation in patients with anterior resection syndrome, achieving a significant improvement of up to 80% on the LARS scale.16

In our series, 70% of patients with incontinence and 80% of those with constipation have subjectively improved their symptoms and quality of life after starting irrigation. These results are higher than those of other studies, such as the Juul and Christensen paper, with a significant improvement of 65% for incontinence, 48% for constipation and 43% in quality of life during the first year of treatment;1 also, the Etherson et al. article showed a 60% improvement in symptoms and quality of life in chronic constipation using long-term irrigation,15 and the Bildstein et al. study reported 51% success in incontinence.17

Despite having a small sample and a short follow-up, this therapy seems to achieve good results for patients in whom first-line treatments are not effective. Therefore, it should be considered a therapeutic step to follow before considering neuromodulation of the posterior tibial nerve, sacral roots, or surgery to create a stoma. In refractory cases, therapeutic steps must be taken, from sacral neuromodulation to repair surgery or the creation of a stoma.

The most frequently reported events include abdominal discomfort, slight anorectal pain and/or bleeding, autonomic dysreflexia (in spinal cord injuries), difficulties inserting the catheter/cone or expelling it, and leaks between irrigations.9 The most feared complication is intestinal perforation, which is more likely during the first months of treatment, although it is very rare (<1/50 000 irrigations). If the patient develops severe abdominal pain or bleeding, therapy should be discontinued and the condition treated as an emergency.11

In our series, no major complications have occurred, and minor complications, such as abdominal pain, have improved over time and by learning the treatment. However, this therapy requires commitment and time, and patients tend to abandon it if they do not notice an improvement early on.

Regarding adherence to treatment, 53% of patients in the Wilson study abandoned therapy over a 5-year follow-up, mainly due to lack of response, leaks, catheter expulsion or balloon rupture, and the mean time of use was 8 months.13 In the studies by Bildstein et al.17 and Christensen,18 only 43% of the patients instructed in irrigation continued to use it one year later, mostly due to lack of response. In the study by Hamonet-Torny et al.,19 62.5% continued irrigation in the long term, and most dropouts occurred in the first month. In the study by Chesnel et al.,20 adherence decreased from 73.9% the first month to 40.1% one year after treatment started.

In our series, the abandonment rates were 30% for incontinence and 20% for constipation, in most cases due to lack of therapeutic response. We believe that these results can be explained by the involvement of the nursing staff, although they can also be justified by the shorter follow-up time of our patients compared to the aforementioned studies.

Therefore, we must emphasize that, in addition to the difficulty of enrolling patients in irrigation and maintaining long-term treatment, a significant commitment and adequate understanding of how it functions is required. Patients sometimes have higher expectations that are not always achieved, leading to disappointment and abandonment of the treatment.

Proper patient selection, good training and monitoring during follow-up, an individualized routine and easy access to staff to resolve any problems that arise or concerns are essential. However, the results of this therapy vary considerably, so it is essential to promote more realistic expectations about its efficacy, limitations and adverse effects.17

The limitations of our study are related to its observational study design of a series of cases treated with a diagnosis and treatment protocol. Another limitation is the small number of cases. Although the sample size was not calculated, our study included all consecutive patients with the diagnoses and disease severity that made them likely to benefit from transanal irrigation. Finally, the follow-up was an intermediate period, and a longer-term follow-up would be desirable as the treatment effectiveness and patient adherence may be reduced over time. We believe that these limitations do not invalidate our results and that transanal irrigation is a useful and effective therapeutic option that is able to improve the symptoms and quality of life of patients with incontinence and chronic constipation. In addition, it is a safe treatment and can be considered a good option in patients with failed conservative treatment, prior to the use of other more invasive options.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from public, private, or non-profit entities.

Conflicts of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank Dr Milagros Carrasco, the first to initiate transanal irrigation our unit, and for helping others understand the importance of improving the quality of life of these patients.