Surgery for retroperitoneal sarcomas should be “enbloc” compartmental, which involves resection of unaffected organs. Its upfront use is key, providing a high percentage of resections with negative margins, resulting in a better local control and increased survival in many patients. Preservation of organs should be done in an individualized manner, especially in the pelvic location, and adapted to the histological aggressiveness of the tumor. Preoperative biopsy is able to establish the diagnosis of sarcoma subtype and consequently an adequate perioperative strategy. These patients should be managed by expert surgeons at referral centers with multidisciplinary units and oncology committees. The use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is not yet well defined, so it is only recommended at referral centers with clinical trials. Currently, this is the only option to offer the best morbidity and mortality rates, as well as possible improvements in the survival of these patients.

La cirugía de los sarcomas retroperitoneales debe ser compartimental «en bloque», lo que implica la resección de órganos adyacentes al tumor. Su empleo «de entrada» permite un elevado porcentaje de resecciones con márgenes negativos, lo que supone un mejor control local y mayor supervivencia en muchos pacientes. La preservación de órganos debe hacerse de forma personalizada, especialmente en la pelvis, y adaptarla a la agresividad histológica del tumor. La biopsia preoperatoria permite establecer el subtipo de sarcoma y una adecuada estrategia perioperatoria. Estos pacientes deben ser manejados por cirujanos expertos en centros de referencia, con unidades multidisciplinarias y comités oncológicos. El uso de quimioterapia y radioterapia aún no está bien definido, por lo que solo se recomienda en centros de referencia con ensayos clínicos. En la actualidad esta es la única opción para ofrecer las mejores tasas de morbimortalidad, y las posibles mejoras en la supervivencia de estos pacientes.

Retroperitoneal and pelvic soft-tissue sarcomas (RPS) are a rare and heterogeneous group of neoplasms whose diagnosis and treatment require multidisciplinary management at referral hospitals.1–4 Treatment almost always requires aggressive initial surgery and recurrences are exceptionally cured with surgery.2,4 The use of chemotherapy (CTx) and/or radiotherapy (RTx) is not yet well defined and therefore only recommended in clinical trials.1,2

In collaboration with oncologists and radiotherapists, the Sarcoma Group of the Spanish Association of Surgeons (Asociación Española de Cirujanos, AEC) has thought it important to create lines of action for RPS, with special emphasis on surgical strategies in these patients.

Diagnosis of Retroperitoneal and Pelvic Soft-tissue SarcomasSoft-tissue sarcomas have an incidence of 3–4 cases per 100000 inhabitants/year; 15% are located in the retroperitoneum, which is the second most frequent location after the extremities. Although in this location there is a great variety of histological subtypes (>70); the most frequent are well-differentiated liposarcoma (WD-LPS), dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DD-LPS) and leiomyosarcoma (LMS). Fibrosarcoma and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, lymphangiosarcoma, malignant schwannoma or hemangiosarcoma are less common.3,5,6

The presence of a palpable abdominal mass, with or without symptoms, is the most frequent clinical finding in RPS. Pelvic sarcomas can produce symptoms due to compression of the bladder, rectum or sacral nerve plexus. Weight loss, gastrointestinal obstruction or the presence of edema in the lower extremities usually occur in locally very advanced stages.7

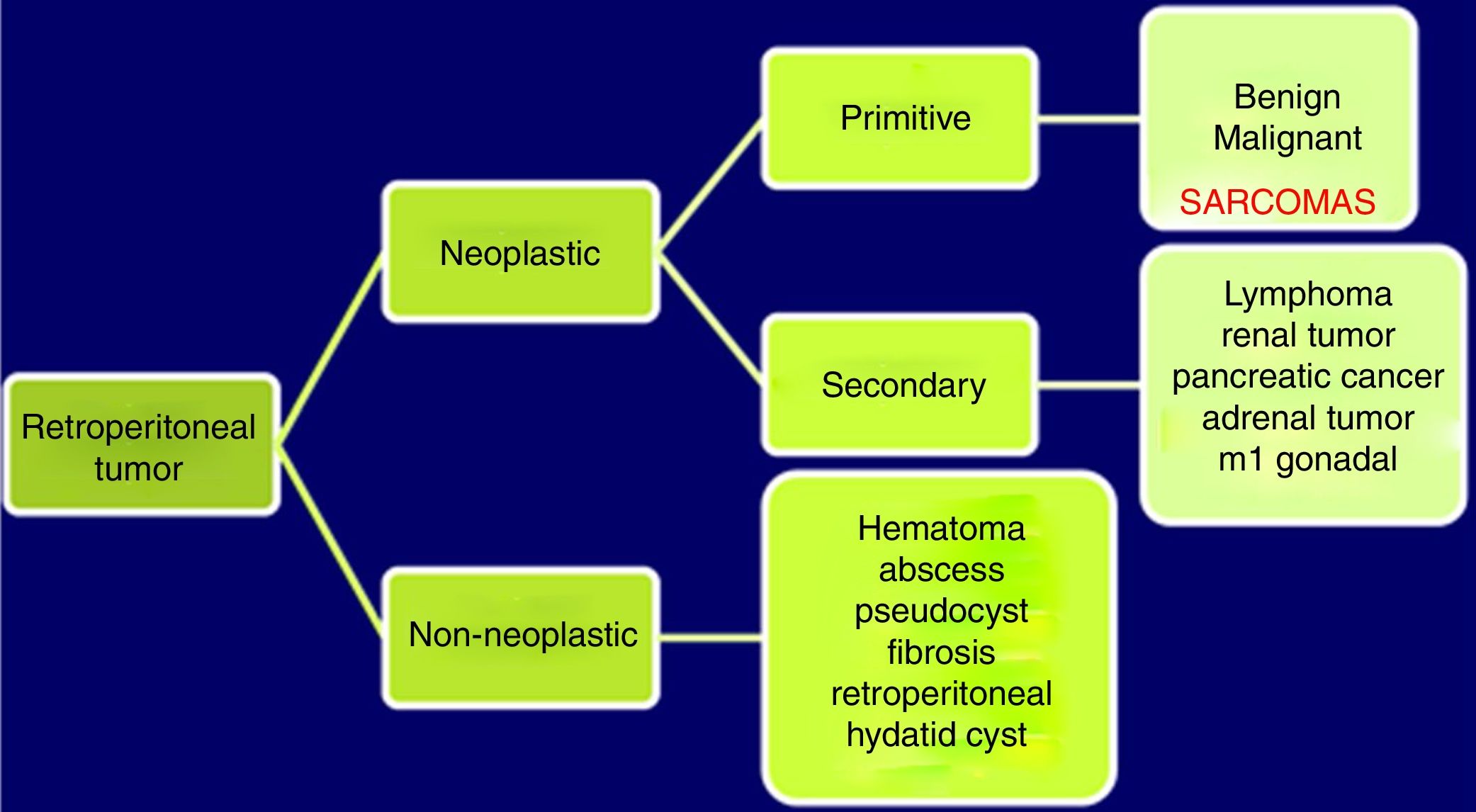

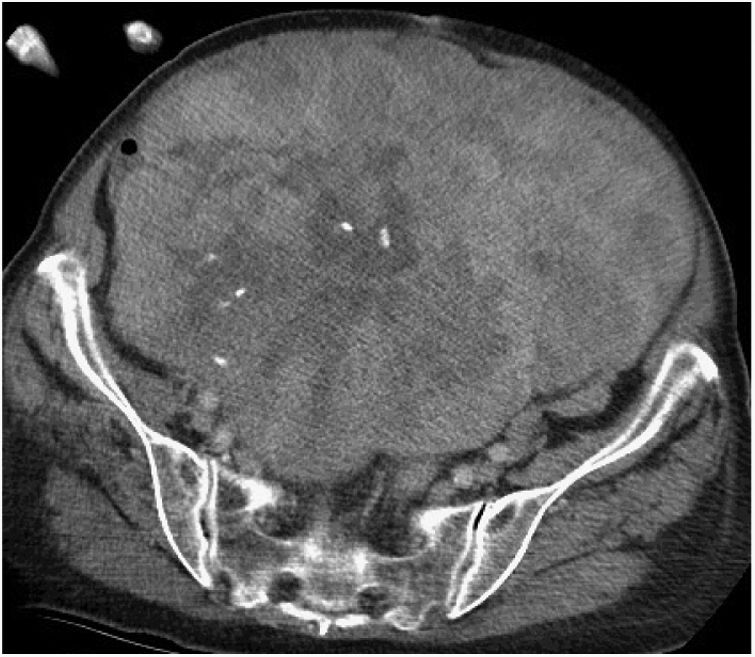

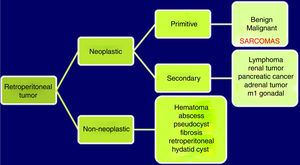

Abdominopelvic and thoracic CT scans, associated with pelvic MRI and PET, are able to define the appearance, size, location and relationship of the tumor with neighboring organs, as well as the presence of invasion of adjacent structures or pulmonary metastatic extension.8,9 The differential diagnosis of RPS includes other malignant lesions in the same location: lymphomas, germ cell tumors, intra-abdominal tumors, desmoid tumors and benign retroperitoneal lesions (Fig. 1).

Preoperative tumor biopsy (tru-cut) is necessary in most cases. It should always be indicated in tumors of uncertain diagnosis, when there is a need for histological subclassification, or before initiating preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. When performing the ultrasound/CT scan-guided biopsy, the transabdominal approach should be avoided due to the risk of dissemination. When the CT scan is very suggestive of WD-LPS, biopsy is not necessary before surgery.7,8

Surgical Treatment of Retroperitoneal and Pelvic Soft-tissue SarcomasComplete R0 surgical resection of the RPS is the only potentially curative treatment, and the initial surgery determines prognosis.9–11 The intimate relationship of the tumor with vital anatomical structures makes this surgery only possible in 70% of patients, and in pelvic sarcomas wide margins are more difficult to obtain.

Local and/or peritoneal recurrence after radical R0 surgery occurs in more than 50% of cases. The recurrence-free time interval marks the evolution of the disease and is longer the more radical the primary surgery. Although the biological aggressiveness of RPS (low/high grade) determines patient prognosis, tumor resection margins influence both the local recurrence rate and mortality.12 Currently, the 5-year locoregional recurrence rate is 41%–58%. Recurrences are usually unresectable and have high associated mortality. Current available data report 5-year locoregional recurrence rates of 41%–58%, with 10-year overall survival rates of 30%.13 It seems clear that R0 resection is the key to local disease control and better survival. However, in 18%–23% of RPS, multifocal tumors and high rates of microscopic invasion of neighboring organs are observed without macroscopic involvement (48% in WD-LPS, 75% DD-LPS and 71% in LMS). This means that many groups consider that the standard surgical resection of RPS must always be considered marginal and associated with high morbidity and mortality rates.14

Theoretical Background for Compartment Surgery in Retroperitoneal and Pelvic Soft-tissue SarcomasRadical en bloc surgery of RPS requires the inclusion of the viscera close to the tumor as an anatomical barrier.15 In the superior retroperitoneal space, this resection includes the colon, small intestine, kidneys, pancreas and/or spleen. Less frequently, it may be necessary to remove the inferior vena cava, aortic artery, pelvic organs (partial or total exenteration) or abdominal/pelvic wall segments (hemipelvectomy).

For a decade, European and American groups have debated about the optimal surgical treatment for RPS, and whether this should be en bloc compartment surgery.16–23 The debate is established in terms of balancing oncological cost/benefit between aggressive surgery and its associated morbidity and mortality. In turn, the biological aggressiveness of RPS itself has a clear impact on the overall survival of these patients, clearly differentiating less aggressive tumors but with a higher rate of local recurrence (WD-LPS grade 1 and 2) from the most aggressive types (DD-LPS and LMS). This would imply, as expert groups currently argue, more personalized surgical strategies based on the biological aggressiveness of these tumors as well as more liberal resection of the organs adjacent to the tumor that are apparently unaffected.16,24

Technical Aspects of Compartment Surgery in Retroperitoneal and Pelvic Soft-tissue SarcomasIn RPS surgery, incomplete resections, intraoperative tumor rupture and hemorrhage requiring large transfusions should be avoided, as they entail a high risk of recurrence. During surgery, unresectability criteria should be assessed. The invasion of the mesenteric vessels or suprahepatic veins and the inability to maintain renal function after ipsilateral nephrectomy contraindicate aggressive surgery. Retroperitoneal vascular LMS may require resection of the vessel itself.25,26

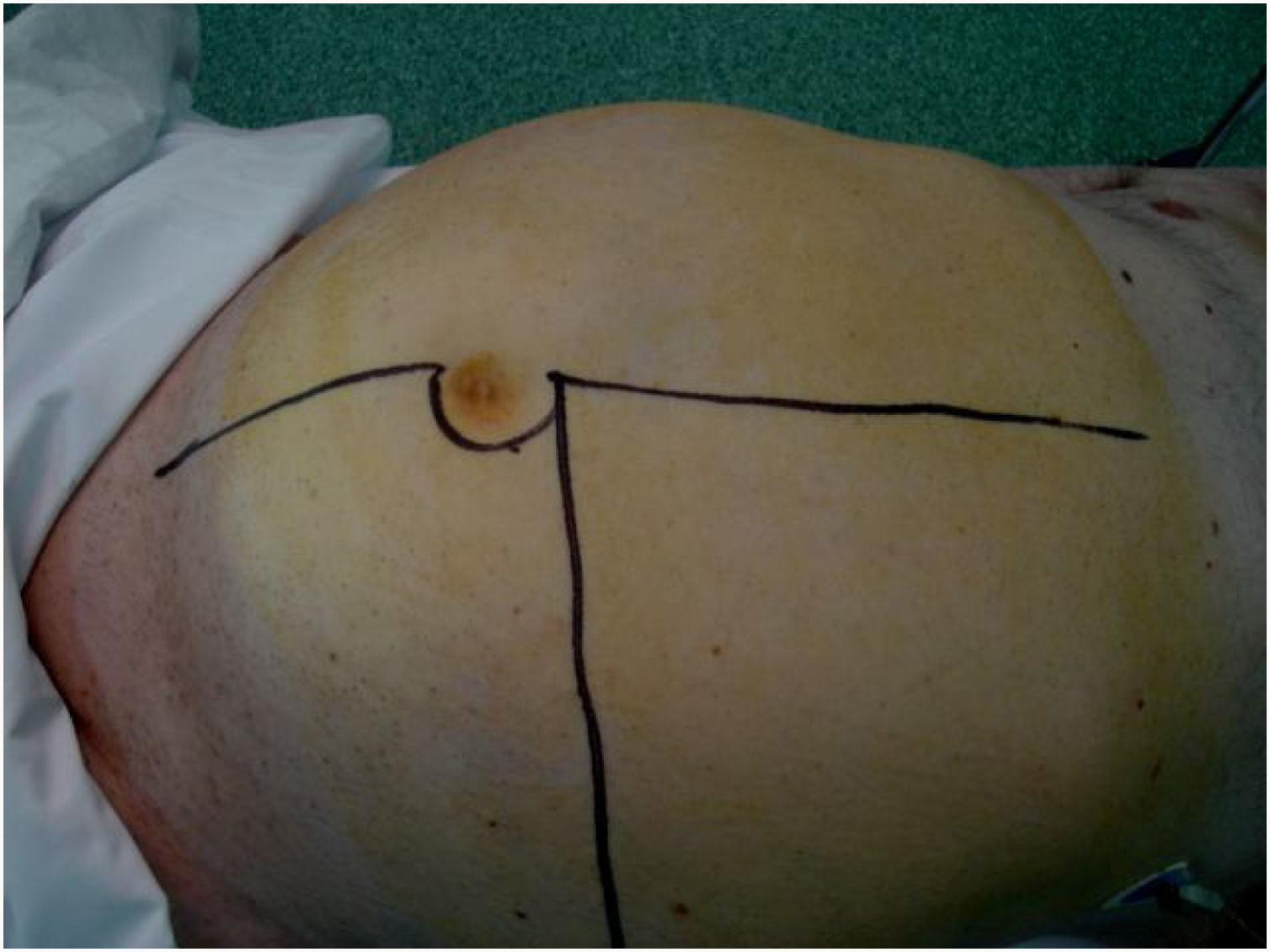

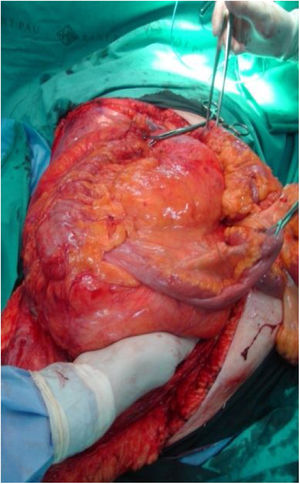

The usual incision for the approach of RPS is a wide midline laparotomy, which is occasionally extended laterally toward the affected side to offer better exposure and vascular control (Fig. 2). In cases with retrohepatic tumor involvement or extension to the thorax, thoracotomy may be necessary, and the inferior vena cava should be assessed up to the right atrium. When the tumor extends to the root of the mesentery, the mesenteric vessels must be initially addressed. The opening of the gastro-colic ligament and the division of the transverse colon at the midline facilitate its control. The iliac vessels should be approached, whenever possible, from their most proximal position and progress distally, ligating all vascular branches that go toward the tumor. In an optimal resection, the inclusion of the kidney is necessary, ligating the renal artery prior to the renal vein.25

Resection of the psoas muscle requires the preservation of the femoral and obturator nerves in order to avoid sequelae. The removal of the entire peritoneum in contact with the tumor is essential. The diaphragm should be resected if invaded by the tumor. There are differences depending on the side where the tumor originates27:

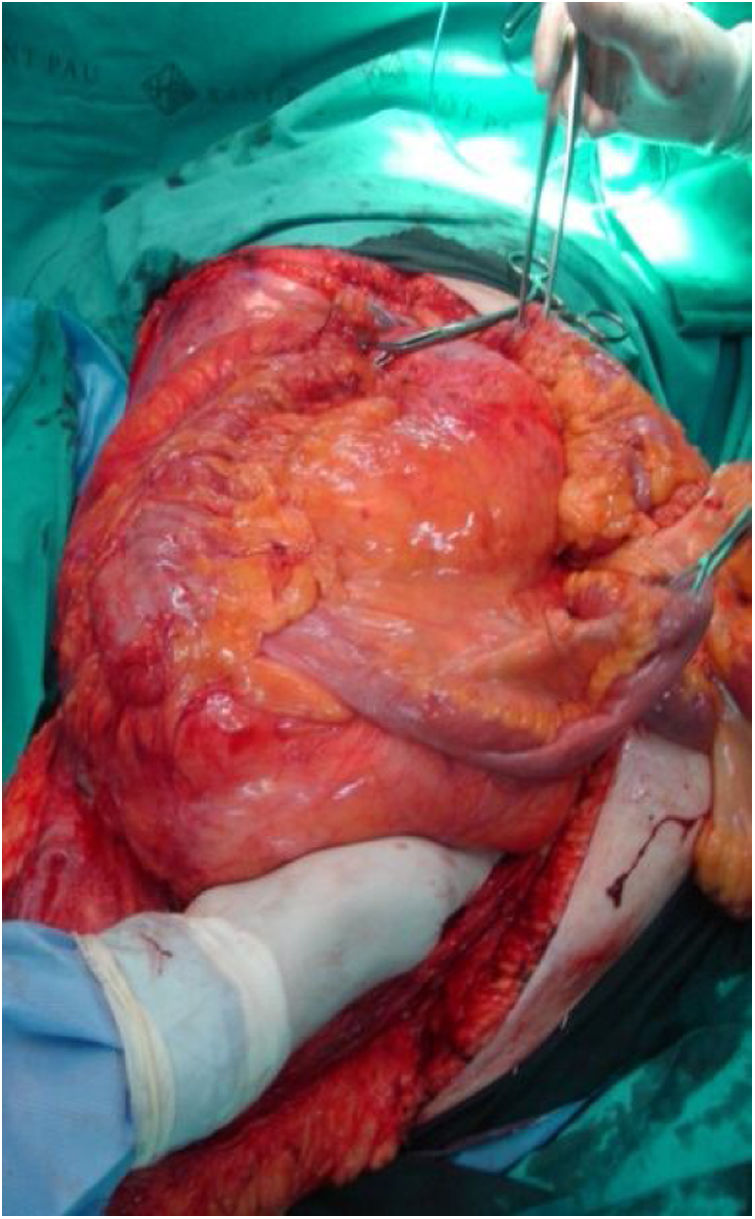

- –

Right side: usually includes the tumor, right colon and kidney (Fig. 3). The release of the duodenum-pancreas provides access to the infrahepatic vena cava. When the duodenum or head of the pancreas is affected by tumor compression, serious damage can occur. Under these circumstances, pancreaticoduodenectomy is not recommended, as it does not improve overall survival.

- –

Left side: usually includes the tumor, left colon and kidney. It is important to release the duodenum extensively in the region of the Treitz angle. When there is invasion, resection requires subsequent duodenojejunostomy. Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy are usually needed for tumors in the upper left quadrant.27

Finally, we should mention specific situations to consider: a) herniation of the tumor into the thorax may obligate a thoracotomy; and b) resection of the inguinal duct structures is necessary in tumors that progress through them.

Pelvic Sarcoma SurgeryExtraperitoneal pelvic RPS represent 18% of the sarcomas.9 In this location, the characteristics of the tumor and its relationship with multiple anatomical structures of the pelvis must be assessed. The most frequent histological types are WD-LPS and DD-LPS, LMS and solitary fibrous tumor28 (Fig. 4).

In this location, surgical planning requires correct staging using an abdominopelvic CT scan and/or a pelvic MRI. Personalized surgery must be designed with the intention of preserving the anatomy and function of the pelvic organs.28

The anatomical limits of the extraperitoneal pelvic cavity are the parietal peritoneum above, the pelvic floor below, the pubis and the inguinal ligaments lying anterior and the sacrum posterior. Due to the close relationship of these tumors with the vascular, bone or visceral structures of the pelvis, it is difficult to achieve wide surgical margins. Resection in the pelvis requires complete excision of the tumor, along with structures directly invaded by it.

Pelvic sarcomas frequently compress the bladder, prostate, seminal vesicles or ureters, but it is rare for these organs to be invaded and need to be removed together with the tumor (<2%). If there is invasion of the bladder, it can be partially resected without affecting its function.28 When the tumor is located in the mesorectum, resection should include the rectum, and abdominoperineal resection may even be necessary in extreme cases.

Pelvic recurrences require more complex surgery and more frequently require visceral resections. Intraoperative identification of the ureters is usually difficult and requires the preoperative placement of ureteral catheters or nephrostomies due to obstructive hydronephrosis, followed by resection of the distal part of the ureter and its reimplantation in the bladder. Tumor fragmentation is related with a higher risk of local recurrence and lower survival rates.16 When tumors are large, recurrent, or adhered to the bony pelvis, they can benefit from a neoadjuvant and/or intraoperative CTx/RTx.

In cases where surgical radicality requires resection of the iliac and/or femoral vessels, subsequent prosthetic vascular restitution will be necessary, which involves greater postoperative morbidity and mortality. If the involvement of main pelvic veins causes occlusion and the development of intense complementary venous circulation, resection without reconstruction is well tolerated, and the use of a venous stent is infrequent. In general, in the absence of lymphatic dissemination, lymphadenectomy is unnecessary.

Nerve resection (femoral/obturator) may be necessary, either because the tumor originates in the nerves (malignant schwannoma) or to achieve radical surgery. When this happens, there are sequelae due to motor deficits caused by this resection.28

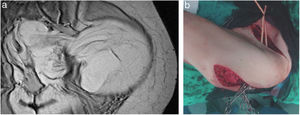

‘Hourglass’ pelvic or extra-pelvic tumors (gluteal/inguinocrural) are a complex scenario, as they progress in one way or another through natural anatomical orifices of the pelvis (obturator, inguinocrural or sciatic notch). In these cases, the surgical approach involves an incision along the iliac crest with a prolongation toward the gluteal region and/or toward the inguinal region, or by a double incision in both areas (Fig. 5A and B). In large WD-LPS, it may be useful to divide the tumor into 2 parts where it passes through the anatomical orifice.

Chemotherapy Treatment in Retroperitoneal and Pelvic Soft-tissue SarcomasSystemic treatment in resectable localized RPS. CTx in this situation is not yet well established and is not recommended outside clinical trials.1–33 We value its usefulness before and after surgery:

- –

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in RPS. There have been no studies assessing its benefit prior to surgery. Patients with histopathological response to neoadjuvant CTx have had better disease-specific survival. In addition, this response is a factor that is considered in the survival estimation nomogram for soft tissue sarcomas, MSKCC.29

- –

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy with regional hyperthermia combined with EIA systemic chemotherapy (etoposide, ifosfamide, doxorubicin) is associated in some cases with a benefit in local and distant SLR, without increasing complications.30

- –

Concomitant CTx/RTx have been studied in phase I trials. A phase I-II study of the Italian Sarcoma Group included resectable RPS treated with high doses of concurrent ifosfamide with RT (50.4Gy), reaching 8% of partial responses and 79% stabilization, improving the DFS to 3 years. However, given the toxicity observed, a phase III trial was chosen exclusively with neoadjuvant RTx (FIII-EORTC 31).31

- –

Therefore, despite the absence of comparative F-III trials on the role of neo-adjuvant CTx, its use is capable of inducing responses, and therefore may facilitate surgery in some cases.32 This is particularly relevant in the case of rescue surgery in initially inoperable RPS or those with uncertain resectability and in tumors with chemosensitive histologies.

- –

Adjuvant chemotherapy in RPS. Its role is not established, since there are no specific studies in this location.33 We currently have nomograms that can help us identify the indication of adjuvant CTx in this location.34

CTx treatment in advanced unresectable and/or metastatic disease. In unresectable localized disease, strategies are limited. Only in cases with a good response to RTx or CTx would surgical resection become a possibility; thus, these would actually be neoadjuvant treatments.35 In definitively unresectable and/or metastatic RPS, CTx is considered palliative. A watch-and-wait approach is a valid option for low-grade tumors that progress slowly, in the elderly or in asymptomatic patients.36

Treatment is similar to that of metastatic SPB from other locations, and the regimen selected depends on histology, patient condition and use of previous CTx.37 In general, doxorubicin should be considered the standard first-line treatment, with a response rate of 25%.2 Recently, the first-line combination of doxorubicin and olaratumab has been approved.37 Finally, other options have been used depending on the histological type, previously administered CTx and patient condition.38–40

Radiotherapy in Retroperitoneal and Pelvic Soft-tissue SarcomasThe RTx used in 25%–30% of RPS could improve the survival and local control of the disease, but until now this concept has had low scientific evidence.41,42 In recent years, contradictory results have been published that generate confusion about their role in RPS.43,44 There are no prospective trials demonstrating its benefit, and the question of application pre- (preRT), intra- (IORT) or post- (postRT) surgery is controversial. In any case, low-grade RPS, such as WD-LPS, do not benefit from RTx.45 In a new study of 9068 patients with RPS, 2 cohorts were compared, one preRT vs surgery alone and the other postRT vs surgery alone. Both schemes showed benefits in terms of OS, and survival was higher with preRT (110 months) versus postRT (89 months).43

preRT. Recent retrospective studies have shown that preRT improves local disease control and survival,41 increases tumor resectability and allows for a greater percentage of en bloc excisions.42 However, the value of the preRT will have to wait for the results of the phase III trial of the EORTC, which will determine the better option between surgery versus preRT and subsequent surgery.

Other schemes, such as surgery with preRT/postRT associated with IORT, offer encouraging results, with local 5-year control of the disease of 40%–60%, but a higher reported rate of chronic neurological toxicity.43 The association of doxorubicin and IORT after resection (phase I trial) achieved R0 in 90% of patients. However, this study does not define the optimal dose of RTx in this combination.43 Finally, modulated intensity radiotherapy (MIRT) makes it possible to scale down the dose of RTx, with a decrease in chronic toxicity.42 Given the absence of clear scientific evidence, the use of preRT in RPS is only recommended in clinical trials.44

postRT. Currently, postRT is not used for several reasons: a) difficulty in planning due to the anatomical disruption involved; b) toxicity is unpredictable due to the movement of the intestine and other organs at risk; and c) a higher dose of RTx is required. With modifiable techniques like MIRT, it is possible to reduce the dose in organs at risk, but in the case of the abdomen it is difficult to avoid high doses in the intestine.46,47

Although there is no scientific evidence, preRT could be considered effective, feasible and less toxic than postRT. Current techniques, such as MIRT, make it possible to increase the radiation dose in areas of high risk of recurrence. However, despite all these considerations, we must wait for the results of the phase III STRASS trial NCT01344018 of the ESMO to define the benefit of RTx in RPS.

Prognosis of Retroperitoneal and Pelvic Soft-tissue Sarcomas and Final ConclusionsThe prognosis of RPS (DFS and OS) varies between different histological forms. The absence of lymph node dissemination in most RPS means that survival in these patients is superior to that of other tumors.48 The initial surgery should always be as radical as possible, as DFS ad OS depend on this, as well as the need for rescue surgeries.49 Each re-operation is associated with greater technical difficulty and a higher percentage of complications and postoperative mortality. Therefore, its indication is only accepted when complete resection of the recurrence can be achieved.9,50

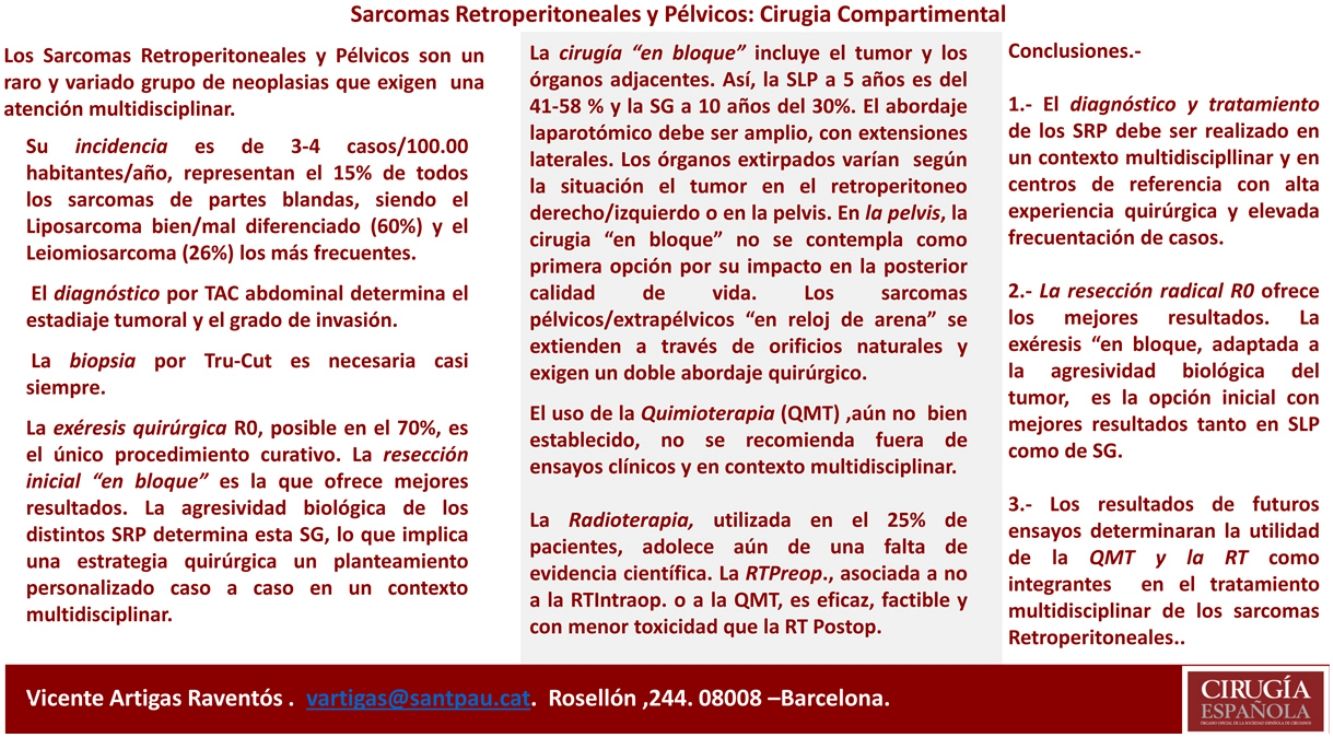

Classically, the histological grade and type and the quality of surgery have been the most important predictive factors. From a surgical point of view, it is necessary to consider that optimal surgery to treat RPS involves complete macroscopic excision (R0 and R1). There are 4 specific prognostic nomograms for RPS, in which the tumor grade and histological subtype appear to be the most important prognostic predictors. However, only the Gronchi et al. nomogram34 has been validated and supported by the AJCC. In this version, the prediction that a patient is alive or free of disease 7 years after surgery is adjusted based on a score of tumor size, histological subtype and grade, patient age and extent of resection35 (Fig. 6).

Finally, it is important to highlight that surgery is still the treatment of choice in RPS, as long as the criteria for surgical radicality are met. This surgery must be performed by experts, with the support of several surgical specialists in a multidisciplinary context and at referral hospitals with a high volume of cases.2 The combination of this surgery with CTx and/or RTx can be effective when the cases are well selected. In complex situations, such as pelvic tumors, the association of surgery with preoperative RTx±IORT helps with local control of the disease.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Asencio Pascual JM, Fernandez Hernandez JA, Blanco Fernandez G, Muñoz Casares C, Álvarez Álvarez R, Fox Anzorena B, et al. Actualización en el manejo de sarcomas retroperitoneales y pélvicos; el papel de la cirugía compartimental. Cir Esp. 2019;97:480–488.