To analyse the relationship between the level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet and the control of cardiovascular risk factors.

MethodA descriptive, observational study was conducted on patients diagnosed with Diabetes Mellitus type 2, with poor blood glucose control and a Body Mass Index greater than 25kg/m2. The relationship between the adherence to the Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular risk factors was evaluated before and after education about the Mediterranean diet. The patients were given a questionnaire on the level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet (the Mediterranean diet score), at the beginning of the study and at 6 month after having education about the Mediterranean diet in the Primary Care medical and nursing clinics. An analysis was carried out on the variables including, gender, age, weight, height, and Body Mass Index, as well as the analytical parameters of blood glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin, total, HDL, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. The relationship between the primary variable, ‘adherence to the Mediterranean diet’, and the rest of the variables was calculated before and after the educational intervention.

ResultsThe initial ‘adherence to the Mediterranean diet score’ in the questionnaire was relatively low (6.22). Excess weight, as well as to have an elevated Body Mass Index are associated with a lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet, as well as low adherence to treatment (p<.00 and p<.02, respectively). The values of HDL cholesterol values increased with greater adherence (p<.04). Elevated LDL and total cholesterol are associated with a lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet (p<.01 and p<.05, respectively), similar to that of elevated triglycerides (p<.00). Elevated baseline blood glucose levels are also associated with low adherence to the Mediterranean diet (p<.04), as well as the increase in glycosylated haemoglobin (p<.06).

Thus the cardiovascular risk increases with low adherence (p<.08).

After the educational intervention, a moderate increase was observed in the adherence to the Mediterranean diet (a score of 6.84) as well as a notable improvement in the control of the cardiovascular risk factors.

ConclusionsAdherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with improved control of cardiovascular risk factors.

Analizar la relación entre el grado de adherencia a la dieta mediterránea y el control de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular.

MétodoEstudio observacional descriptivo en pacientes diagnosticados de diabetes mellitus tipo 2 con mal control glucémico e índice de masa corporal superior a 25kg/m2, en el cual se evalúa la relación entre la adherencia a la dieta mediterránea y factores de riesgo cardiovascular, antes y después de una educación sobre dieta mediterránea. Se les administra una encuesta de grado de adherencia a la dieta mediterránea, «score de dieta mediterránea», al inicio del estudio y a los 6 meses, tras realizar una educación sobre dieta mediterránea en las consultas médicas y de enfermería de Atención Primaria. Se analizan las variables edad, sexo, peso, talla e índice de masa corporal, así como los parámetros analíticos de glucemia, hemoglobina glucosilada, colesterol total, cHDL, cLDL, triglicéridos. Se relaciona la variable principal «adherencia a la dieta mediterránea» con el resto de las variables, antes y después de la denominada intervención educativa.

ResultadosInicialmente la puntuación de la encuesta de adherencia a la dieta mediterránea fue relativamente baja (6,22). Tanto el exceso de peso como tener un índice de masa corporal elevado están en relación con una baja adherencia a la dieta mediterránea, así como con una baja adherencia terapéutica (p<0,00 y p<0,02, respectivamente); los valores de cHDL aumentan con una mayor adherencia (p<0,04); los valores de cLDL y colesterol total elevados están relacionados con una menor adherencia a la dieta mediterránea (p<0,01 y p<0,05, respectivamente), al igual que los triglicéridos elevados (p<0,00). Las cifras elevadas de glucemia basal también están relacionadas con la baja adherencia a la dieta mediterránea (p<0,04), así como el incremento de la hemoglobina glucosilada (p<0,06).

Por tanto, el riesgo cardiovascular aumenta con la baja adherencia (p<0,08).

Tras la intervención educacional observamos un aumento moderado de la cumplimentación de la dieta mediterránea (puntuación de 6,84) y una notable mejoría en el control de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular.

ConclusionesLa adherencia a la dieta mediterránea está en relación con el mejor control de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular.

The Mediterranean diet (MD) has traditionally been defined as the dietary model of the early 1960s in the countries of the Mediterranean region (Greece, southern Italy and Spain). Although there is no single MD, its main characteristics are considered to be: (a) high consumption of fats (including over 40% of total energy), primarily in the form of olive oil; (b) high consumption of unrefined cereals, fruits, vegetables, pulses and nuts; (c) moderate–high consumption of fish; (d) moderate–low consumption of white meat (poultry and rabbit) and dairy products, primarily in the form of yoghurt or fresh cheeses; (e) low consumption of red meat and meat products and (f) moderate consumption of wine with meals. This model and the proportions of the different foods it comprises can be seen graphically in the form of a “food pyramid”.1–4

Important changes were made in the latest update. The first is in relation to cereals, which should mainly be whole grain, and the second relates to dairy products, which should be skimmed. Other aspects have also been added that relate to lifestyle, such as physical exercise, sociability and sharing meals with family and friends.4,5

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the epidemics of the twenty-first century, leading to a need to assess the effects of the MD on the prevention of this disease. A study of 418 non-diabetic participants has therefore been conducted. At five years, the incidence of DM in the three groups (MD+olive oil, MD+nuts and low-fat diet) was 10.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.1–15.1), 11.0% (95% CI: 5.9–16.1) and 17.9% (95% CI: 11.4–24.4). The adjusted hazard ratios (HRa) were HRa=0.49 (95% CI: 0.25–0.97) and HRa=0.48 (95% CI: 0.24–0.96) in the MD+olive oil and MD+nuts groups in comparison with the low-fat diet group. In both MD groups, the incidence of DM was definitively reduced by 52% (95% CI: 27–86) versus the low-fat diet group. These changes were observed in the absence of variations in body weight and without significant changes in physical activity. It therefore appears that a MD intervention is a highly effective instrument for DM prevention in subjects with high vascular risk.6–10

In its 2014 general recommendations, the American Diabetes Association11 makes explicit reference to the MD, citing improved glycaemic control and cardiovascular benefits in patients with DM.

Esposito et al.8 conclude in their article that, in patients with a recent diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a low-carbohydrate MD clearly offers a greater reduction in glycated haemoglobin levels and a higher rate of remission of diabetes, as well as a delay in the use of medications to treat the disease, in comparison with patients who followed a low-fat diet.

Scientists at the Institut de Recerca Biomèdica de Lleida [Lleida Biomedical Research Institute] (IRBLleida), Institut d’Investigació en Ciències de la Salut Germans Trias i Pujol [Institute for Health Science Research Germans Trias i Pujol] (IGTP) in Badalona and the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas [Diabetes and Associated Metabolic Diseases Networking Biomedical Research Centre] (CIBERDEM) have demonstrated that adult patients with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) have healthier dietary habits and better adherence to the MD than non-diabetic subjects. The study, published in the European Journal of Nutrition,9,10 correlates this adherence with these types of patients. The investigation also positively assessed the performance of physical activity by people with T1DM. In addition, the investigation shows the influence of patients’ place of residence on adherence to the MD, with those resident in non-urban areas having a better dietary model.

Although, as we have said, the MD has systematically been found to aid in protection against cardiovascular, inflammatory and metabolic diseases, as well as numerous chronic degenerative diseases,12–20 its protective effect has differed greatly between studies.15,18,19 Consequently, a large number of systems for scoring adherence to the Mediterranean diet are being created in order to determine how diet and health are related. However, recent publications indicate that some of these scoring systems do not offer a solid predictive capacity with respect to mortality or disease, which calls into question their quality.19–23 This view has been corroborated by the recent systematic review by Zaragoza-Martí et al.,24 which showed that most scoring systems lack information on scale quality attributes. This group of authors propose that greater attention needs to be given to the way in which these scoring systems are created, indicating as points for improvement: first, a common criterion needs to be established to identify the components that make up the MD; second, various elements need to be unified: the number of components (nutrients, foods or food groups), classification categories for each population, measurement scale, statistical parameters (mean, median, terciles, etc.) and each component's (positive or negative) contribution to the total score14,19–26 and, finally, given the high degree of heterogeneity in the MD across different countries, additional confirmatory analyses are needed that use biomarkers to validate this dietary model.

In this work, we propose, for ease of use, using the score in a group of patients with poor control of analytical parameters (blood glucose, glycated haemoglobin, total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, triglycerides), as well as assessing the degree of adherence to the MD and other variables that may have an influence.

MethodA descriptive observational study in patients with poor glycaemic control (glycated haemoglobin above 7%) from various health centres in Albacete and Cuenca was conducted. Patients who were diagnosed with T2DM and who were overweight (body mass index [BMI] above 25kg/m2) or obese (BMI above 30kg/m2) who met the diagnostic criteria in use at the time of submission and who were being followed up by the Health Centre during the period from January 2017 to May 2018 were included, regardless of their age or other comorbidities.

They were administered the “Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener”,27 a Mediterranean diet score, at the beginning of the study and at six months, after providing education on the MD in medical and primary care nursing consultations, which consisted of assessing adherence to the MD using a Mediterranean diet score based on the 14-point test. A score of nine points or more is a good level of adherence, and values of eight or less are considered poor adherence. Over six months, patients were seen monthly for weight and glycaemic control, and the information on diet and lifestyle was reiterated, with particular reference to foods in the MD.

As of this year, the score is also validated in the British population.

The variables age, gender, weight, height and BMI were analysed, as were the analytical parameters blood glucose, glycated haemoglobin, total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C and triglycerides.

The primary endpoint “MD adherence” was correlated with the other variables before and after the educational intervention.

Statistical analysisAn ad hoc database was designed in Excel (Microsoft®) and used to archive all the data collected and the patients’ identifying data, which were protected and encrypted. The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS® (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 23.0.

A descriptive analysis of the variables of interest was performed, observing their distribution in order to be able to define cut-off points preferably based on typical scores and to detect abnormal or erroneous values. The qualitative variables were presented using the frequency distributions of the percentages in each category, while for quantitative variables the analysis explored whether they followed a normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and gave measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation or percentiles).

The association between these factors was investigated using hypothesis testing, comparing proportions when both were qualitative (Chi-squared, Fisher's exact test), means when one was quantitative (Student's t-test, ANOVA) and, if they did not follow a normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal–Wallis and Friedman's test for repeated measures. Linear regression tests were performed when the dependent variable was quantitative. For qualitative variables, the relative risk (RR) for the different proportions and their CIs were calculated. The analysis was complemented with graphical representations. The statistical significance level for this study was p≤0.05.

Ethical aspectsThe study was conducted in accordance with recognised standards of ethics and good clinical practice. The data were protected from non-permitted uses by people external to the investigation and confidentiality was respected with regard to personal data protection and Law 41/2002, of 14 November, regulating patient autonomy and rights and obligations relating to clinical information and documentation. The information generated in this study was therefore considered to be strictly confidential between the participating parties.

ResultsOne hundred and seven diabetic patients took part over six months, of whom 45.55% were male, with a mean age of 61.16±23 years.

BMI at the start was 31.66kg/m2, with a mean baseline glycated haemoglobin of 8.55%.

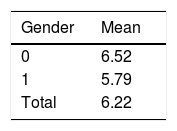

Baseline dataScores of the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener were relatively low (6.22), with no statistically significant difference found by gender (6.52 for women and 5.79 for men) (p<0.13) (Table 1).

Although it is clear that increasing age improves adherence to the MD, no significant difference was found (p<0.08), nor was there any evolution of diabetes with age (p<0.37).

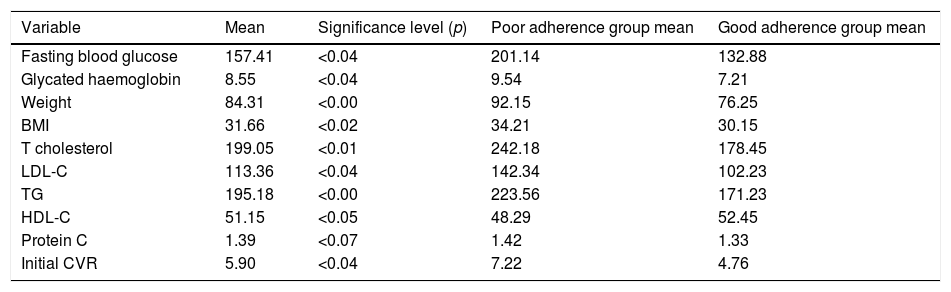

The results for the variables at the start are shown in Table 2 together with the significance level (p).

Relationship between initial values and the variable “adherence to the Mediterranean diet”.

| Variable | Mean | Significance level (p) | Poor adherence group mean | Good adherence group mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting blood glucose | 157.41 | <0.04 | 201.14 | 132.88 |

| Glycated haemoglobin | 8.55 | <0.04 | 9.54 | 7.21 |

| Weight | 84.31 | <0.00 | 92.15 | 76.25 |

| BMI | 31.66 | <0.02 | 34.21 | 30.15 |

| T cholesterol | 199.05 | <0.01 | 242.18 | 178.45 |

| LDL-C | 113.36 | <0.04 | 142.34 | 102.23 |

| TG | 195.18 | <0.00 | 223.56 | 171.23 |

| HDL-C | 51.15 | <0.05 | 48.29 | 52.45 |

| Protein C | 1.39 | <0.07 | 1.42 | 1.33 |

| Initial CVR | 5.90 | <0.04 | 7.22 | 4.76 |

We can see, therefore, that both excess weight and having a high BMI are associated with poor adherence to the MD, as well as poor therapeutic adherence (p<0.00 and p<0.02, respectively).

HDL-C increased with better adherence (p<0.04).

We can also see that high LDL-C and total cholesterol are related to poorer adherence to the MD (p<0.01 and p<0.04, respectively), as are high triglycerides (p<0.00). Elevated baseline blood glucose figures are also associated with poor adherence to the MD (p<0.04), as is increased glycated haemoglobin (p<0.03).

In the same vein, cardiovascular risk (CVR) also increased with poor adherence to the MD (p<0.03).

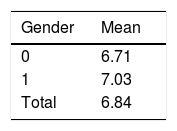

Post-intervention dataAdherence to the MD is 6.84 (+0.62), with no significant difference between the genders (Table 3).

No significant difference can be seen (p<0.12) between MD adherence and years since the diagnosis of DM.

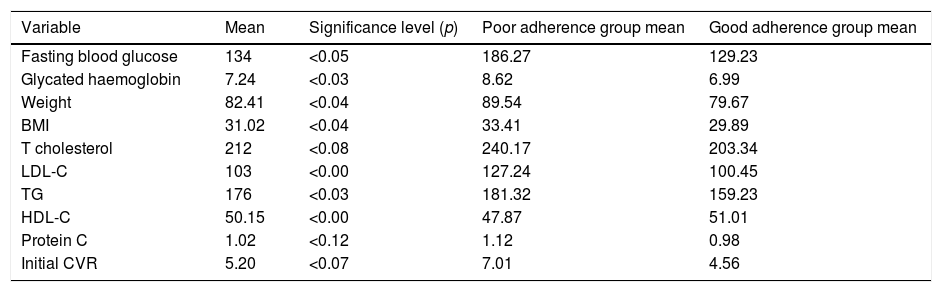

In Table 4, we can see how a minimal intervention to improve adherence to the MD improves both anthropometric (weight and BMI) and analytical (blood glucose, glycated haemoglobin and lipids) parameters.

Relationship between post-intervention values and the variable “adherence to the Mediterranean diet”.

| Variable | Mean | Significance level (p) | Poor adherence group mean | Good adherence group mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting blood glucose | 134 | <0.05 | 186.27 | 129.23 |

| Glycated haemoglobin | 7.24 | <0.03 | 8.62 | 6.99 |

| Weight | 82.41 | <0.04 | 89.54 | 79.67 |

| BMI | 31.02 | <0.04 | 33.41 | 29.89 |

| T cholesterol | 212 | <0.08 | 240.17 | 203.34 |

| LDL-C | 103 | <0.00 | 127.24 | 100.45 |

| TG | 176 | <0.03 | 181.32 | 159.23 |

| HDL-C | 50.15 | <0.00 | 47.87 | 51.01 |

| Protein C | 1.02 | <0.12 | 1.12 | 0.98 |

| Initial CVR | 5.20 | <0.07 | 7.01 | 4.56 |

In terms of the link between these and the MD adherence endpoint, we can see that both being overweight and obese are associated with poor adherence to the MD and poor therapeutic adherence in general (p<0.04). HDL-C increased notably with better adherence (p<0.00).

We can also see that higher LDL-C values (p<0.00) are associated with poor MD adherence, as are elevated triglycerides (p<0.03); no association with total cholesterol was found in the post-intervention measurement (0.09).

The high baseline blood glucose and glycated haemoglobin figures are related to poor adherence to the MD (p<0.04 in both cases). A tendency can be observed for CVR to increase with poor adherence, although this relationship is not significant (p<0.07).

DiscussionThe MD is in fashion, and its value for health has been reinforced internationally in recent years. The PREDIMED study27–30 conducted in Spain in more than 7000 patients, concluded that, in people with high CVR, an MD supplemented with extra virgin olive oil or nuts reduces the incidence of severe cardiovascular episodes, demonstrating the health benefits of Spain's traditional diet. In its 2014 general recommendations, the American Diabetes Association11 makes explicit reference to the MD, citing improved glycaemic control and cardiovascular benefits in patients with DM.

In this article, it is shown that diabetic patients with poor control have a very low degree of adherence to the MD; likewise, poorly controlled diabetic patients (baseline blood glucose of 157.41 and glycated haemoglobin of 8.55%) who are also obese (weight 84.31kg and BMI 31.66kg/m2) and have altered lipid parameters have poor adherence to the MD (6.22).

We have a diet adapted to our environment, about which we have level A evidence for the improvement of the glycaemic profile and insulin sensitivity, both in prediabetic patients and those with DM, and that has been found to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events and other complications of DM. We also have a quick and easy tool for working with this diet in our consultations, that has been found to be useful for advising and increasing adherence to the MD, but, even so, as we see in our study, adherence is generally poor.

There is ample evidence of the effect of the MD on hydrocarbon metabolism. Multiple cohort studies have found a preventive effect on the incidence of T2DM with this diet. A meta-analysis carried out by Koloverou et al.29–31 in 2014 on one clinical trial and nine cohorts found a 23% reduction in the risk of developing DM among participants with better adherence to the MD (95% CI: 11–34). These results hold true for the subgroup analysis performed by geographic region, number of variables controlled for and participants’ pre-existing risk. A clinical trial32 conducted in our environment in patients at high risk of developing DM, with an MD-based intervention, found a 36% reduction in the risk of developing DM. The analysis of the 3541 participants without DM at the start of the study in the PREDIMED trial revealed a 40% reduction in the risk of developing DM in the MD supplemented with olive oil group.33

Although less numerous, we also have studies on glycaemic control in already-diagnosed cases. A clinical trial conducted by Esposito et al.34 in patients with newly-diagnosed T2DM assigned to the MD found, after four years of follow-up, a HRa of 0.70 (95% CI: 0.59–0.90) for requiring drugs for control, after adjusting for weight loss, compared to a low-fat diet (<30% of calories in the form of fats). Moreover, the patients assigned to the intervention group had better glycated haemoglobin levels: −0.4% (95% CI: −0.4% to −0.1%), insulin sensitivity and adiponectin in blood. Participants in the two groups presented no differences with regard to reducing and maintaining their caloric intake.

Another clinical trial conducted by Elhayany et al.32 obtained, after one year of follow-up, a reduction in glycated haemoglobin in the low-carbohydrate MD group that was greater (from 8.3 to 6.3) than that achieved by the group following the diet recommended by the American Diabetes Association in 2003 (from 8.3 to 6.7; p<0.02) and also achieved a greater reduction in fasting blood glucose levels (77.29 versus 55.3mg/dl), although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.08).

A meta-analysis performed by Ajala et al.35 in 2013 compared 20 clinical trials with different diet-based interventions to improve glycaemic control. All of them found better results in the intervention group than in the control group, with reductions in glycated haemoglobin of 0.12% (p=0.04), 0.14% (p=0.00), 0.28% (p<0.00) and 0.41% (p=0.00) for a low-carbohydrate diet, low glycaemic index, high-protein diet and MD, respectively. A greater reduction in glycated haemoglobin was observed in studies with an MD.

Another meta-analysis published in 201536 analysed nine clinical trials that compared the MD with a control diet for glycaemic control, and noted a reduction in glycated haemoglobin of half a percent in favour of the MD (95% CI: from −0.46 to −0.14%) and in fasting blood glucose levels of 13mg/l (95% CI: 3.78) with a reduction in insulinaemia of 0.55μU/ml.

In our study, we can observe how a minimal educational intervention in favour of the MD, without modifying other treatments, increases the degree of adherence from 6.22 to 6.84, which in turn improves blood glucose parameters: baseline blood glucose from 157.41 to 134 and glycated haemoglobin from 8.55 to 7.24%.

Good control in diabetic patients consists not only of controlling fasting blood glucose or glycated haemoglobin levels; control of other CVR factors is as, or more, important than glycaemic control, and the MD has been shown to also be effective at controlling these CVR factors.

There is sufficient literature recounting improved control of CVR factors with the MD, both in cohort studies and trials. Some include a large number of patients with DM.33,37–39

Some further studies suggest that an MD intervention eliminates the harmful effect of obesity on CVR.38,39 In our study, we can see that weight changed from 84.31 to 82.41kg and BMI from 31.66 to 31.02kg/m2.

Another clinical trial conducted in diabetics, the Look AHEAD study,40 found no statistically significant differences between the intervention group (low-fat, low-calorie diet with the aim of weight loss) and the control group (standard of care) for a primary endpoint similar to that of the PREDIMED study,33,37 in spite of the intervention group having achieved greater weight loss and better control of most risk factors. We must not forget that weight loss was not the PREDIMED trial's objective.

In terms of microvascular complications of T2DM, after a median of six years of follow-up, the PREDIMED trial observed a 44% reduction in diabetic retinopathy in the MD and olive oil group,40,41 although no association was found with kidney failure.

We have also found improvements in lipid parameters: triglycerides from 195.18 to 176, LDL-C from 113.36 to 103 and HDL-C from 50.15 to 51.15; however, we detected a slight elevation in total cholesterol from 199.05 to 212.

Having demonstrated the efficacy of an MD model in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and its main risk factors,42 we must dedicate more attention to healthy lifestyle- and diet-based measures.

It would therefore be fitting to propose the application of a cardiovascular prevention programme with a diet-based intervention similar to that used in the PREDIMED study in our medical consultations. The help of dietitians and/or nursing staff could be enlisted to educate patients to follow a traditional MD, complemented with an active intervention intended to increase their physical activity. It is possible that more extensive use of healthy lifestyle- and diet-based measures would not only reduce healthcare expenditure, but would also achieve a reduction in comorbidities and the adverse effects of drugs.

FundingThere is no external funding.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

Please cite this article as: Celada Roldan C, Tarraga Marcos ML, Madrona Marcos F, Solera Albero J, Salmeron Rios R, Celada Rodriguez A, et al. Adherencia a la dieta mediterránea en pacientes diabéticos con mal control. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arteri.2019.03.005