We present cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence and mortality rates reported for South America stratified by country, sex, and urban/rural location in a multinational cohort included in the Population Urban Rural Epidemiological Study (PURE). This study included 24718 participants from 51 urban and 49 rural communities in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Colombia and the mean follow-up was 10.3 years. CVD incidence and mortality rates were calculated for the total cohort and in subpopulations. Hazard ratios and population attributable fractions (PAFs) for CVD and death were examined for 12 modifiable risk factors, grouped as metabolic (hypertension, diabetes, abdominal obesity, and high non-HDL cholesterol), behavioural (smoking, alcohol, diet quality, and physical activity) and other (education, household air pollution, strength, and depression). The leading causes of death were CVD (31.1%), cancer (30.6%), and respiratory diseases (8.6%). Approximately 72% of the PAFs for CVD and 69% of the PAFs for deaths were attributed to 12 modifiable risk factors. For CVD, the main PAFs were due to hypertension (18.7%), abdominal obesity (15.4%), smoking (13.5%), low muscle strength (5.6%), and diabetes (5.3%). For death, the main PAFs were smoking (14.4%), hypertension (12.0%), low educational level (10.5%), abdominal obesity (9.7%), and diabetes (5.5%). Cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and respiratory diseases account for more than two-thirds of deaths in South America. Men have consistently higher CVD rates and mortality than women. A large proportion of CVD and premature deaths could be avoided by controlling metabolic risk factors and smoking, which are the main risk factors in the region for both CVD and all-cause mortality.

Presentamos las tasas de incidencia y mortalidad por enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) que se han reportado para Sudamérica estratificadas por país, por sexo y por ubicación urbana o rural en una cohorte multinacional incluida en el estudio Poblacional Urbano Rural Epidemiológico (PURE). Este estudio incluyó a 24.718 participantes de 51 comunidades urbanas y 49 rurales de Argentina, Brasil, Chile y Colombia y el seguimiento medio fue de 10,3 años. La incidencia de ECV y las tasas de mortalidad se calcularon para la cohorte total y en subpoblaciones. Se examinaron las razones de riesgo y las fracciones atribuibles a la población (FAP) para ECV y para muerte por 12 factores de riesgo modificables, agrupados como metabólicos (hipertensión, diabetes, obesidad abdominal y colesterol no HDL alto), conductuales (tabaco, alcohol, calidad de la dieta y actividad física) y otros (educación, contaminación del aire en el hogar, fuerza y depresión). Las principales causas de muerte fueron ECV (31,1%), cáncer (30,6%) y enfermedades respiratorias (8,6%). Aproximadamente el 72 % de la FAP para ECV y el 69 % de la FAP para muertes se atribuyeron a 12 factores de riesgo modificables. Para ECV los principales FAP se debieron a hipertensión (18,7 %), obesidad abdominal (15,4 %), tabaquismo (13,5 %), baja fuerza muscular (5,6 %) y diabetes (5,3%). Para muerte, los principales FAP fueron tabaquismo (14,4%), hipertensión (12,0%), baja escolaridad (10,5%) obesidad abdominal (9,7%) y diabetes (5,5%). Las enfermedades cardiovasculares, el cáncer y las enfermedades respiratorias representan más de dos tercios de las muertes en Sudamérica. Los hombres tienen tasas de ECV y mortalidades consistentemente más altas que las mujeres. Una gran proporción de ECV y muertes prematuras podría evitarse mediante el control de los factores de riesgo metabólicos y el consumo de tabaco, que son los principales factores de riesgo en la región tanto para ECV como para mortalidad de cualquier causa.

In recent decades, rapid urbanisation in South America has resulted in lifestyle changes, an increased burden of cardiometabolic risk factors in the population, and increased contribution of noncommunicable diseases to total morbidity and mortality.1–3 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been identified as the leading cause of death in South America.4 However, while most available data do not allow direct comparisons on the presence of risk factors, data on mortality rates are more robust.5–7

The burden of CVD, premature death and their determinants differ between countries with different levels of socioeconomic development, in men versus women, and in populations living in urban or rural areas.8 Therefore, to implement health policies aimed at preventing CVD and reducing premature mortality, up-to-date data are needed on whether risk factors vary between countries, by sex, and by urban-rural location. In addition, region-specific data are needed to identify modifiable risk factors that are common across the region and possibly different from those observed in other regions of the world,8 applying standardised methods for population sampling, data collection, and outcome evaluation. In this regard, the Prospective Urban-Rural Epidemiology Study (PURE) has collected a wealth of data on the determinants of chronic noncommunicable diseases and clinical outcomes in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Colombia, in communities that make up a geographically diverse population that allows us to study CVD, deaths, and their determinants.

In this article we summarise the PURE study data for the four South American countries included9 and analyse the most relevant results on CVD incidence and mortality rates in Latin America.

MethodsThe multinational PURE cohort included 24,718 participants from 51 urban and 49 rural communities in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. The mean follow-up was 10.3years. CVD incidence and mortality rates were calculated for the overall cohort and in subpopulations. Hazard ratios and population attributable fractions (PAFs) for CVD and for death were examined for 12 common modifiable risk factors, grouped as metabolic (hypertension, diabetes, abdominal obesity, and non-HDL high cholesterol), behavioural (smoking, alcohol, diet quality, and physical activity), and other factors (education, household air pollution, strength, and depression). At recruitment, data were collected using standardised questionnaires to document the presence of risk factors at individual, household, and community levels. History of CVD at baseline was defined by self-report of myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke. Hypertension was defined by self-report of history of hypertension, by blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, or by use of antihypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined by fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dl, self-reported history of diabetes, or treatment with hypoglycaemic agents. Waist and hip circumferences were measured using standardised protocols, and abdominal obesity was defined by a waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) of .9 in men and .85 in women. Smoking and alcohol use were collected and quantified by self-report, and the dietary score used was that validated and reported previously. Physical activity was measured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, and educational level was used as a predictor of socioeconomic status. Prehensile strength was measured with a JAMAR dynamometer, while air pollution was assessed indoors and defined as the use of paraffin or solid fuels for cooking. Depression was defined as a score of at least five out of eight symptoms of the International Composite Diagnostic Interview.

ResultsThe median age of the population was 51.4 years, and 61.4% were female. Of the population, 57.4% lived in urban areas and 59.5% had primary education or less. A history of smoking was reported in 43.4% and a history of alcohol consumption in 52.0%. The average diet score was 4.71 out of a total score of 8, and 13.8% had low levels of physical activity. Hypertension was present in 46.5%, and 9.4% had diabetes. Mean body mass index was 28.2 kg/m2 (SD: 5.5) and 65.9% met the definition of abdominal obesity based on waist/hip ratio. Mean non-HDL cholesterol was 155 mg/dl (SD: 42.4), mean grip strength was 31.5 kg, and 11.4% were exposed to household air pollution from cooking with solid fuels.

Argentina had the lowest educational levels and the highest tobacco and alcohol consumption. Brazil had the highest prevalence of hypertension and depression. Chile had the lowest quality of diet, physical activity levels, and grip strength, and the highest level of non-HDL cholesterol, prevalence of abdominal obesity and diabetes, and exposure to household air pollution. In men, alcohol and smoking were higher than in women, physical activity was lower and diet quality was similar. Metabolic risk factors (abdominal obesity, blood pressure levels, hypertension, and diabetes) were more common in men, as was grip strength. There were more women in urban areas (64.7%) than in rural areas (56.8%), and participants in rural areas had lower levels of education and greater exposure to household air pollution. Depression, smoking, and low levels of physical activity were more prevalent in urban areas, while diet quality, alcohol consumption, and cardiometabolic risk differed only modestly between urban and rural areas.

Over a mean follow-up of 10.3 years (mean follow-up ranged from 8.3 to 10.6 years) there were 1,859 deaths and 1,149 CVD events. The overall age- and sex-standardised incidence of a CVD event was 3.34 (CI 95%: 3.12–3.56) per 1,000 person-years, with a range of 3.07 (CI 95%: 2.68–3.47). The incidence of CVD was higher in men (4.48 [CI 95%: 4.07–4.90]) compared to women (2.60 [CI 95%: 2.34–2.85]), which was consistent across the countries. Some countries had a higher incidence of CVD in urban areas, while in others the highest rates were observed in rural areas.

Most of the deaths were attributable to CVD (31.1%), cancer (30.6%), or respiratory diseases (8.6%). CVD was the most common cause of death in men, while cancer was the most common cause of death in women.

The mortality rate in the overall sex- and age-standardised cohort was 4.90 (CI 95%: 4.64–5.17) per 1,000 person-years. The mortality rate (per 1. 000 person-years) was highest in Argentina (5.98 [IC 95%: 5.45–6.51]), and lowest in Chile (4.07 [IC 95%: 3.47–4.68); it was higher in men (6.33 [IC 95%: 5.85–6.82]) than in women (3.96 [CI 95%: 3.65–4.26), and equally higher in rural areas (5.49 [CI 95%: 5.06–5.92) than in urban areas (4.60 [CI 95%: 4.26–4.95).

A total of 23,608 participants had no history of baseline CVD and 16,453 (70%) had complete data on all included risk factors. Of the 12 modifiable risk factors examined for CVD, the largest association (HR > 2) was with current tobacco use, with moderate associations (HR > 1.5) for hypertension and diabetes, and minor associations (HR < 1.5) for low physical activity, decreased grip strength, and abdominal obesity. For death, the strongest association was also with current tobacco use, with moderate associations with diabetes and lower physical activity, while the lowest associations were observed for hypertension, abdominal obesity, low education, and the lowest quintile of strength.

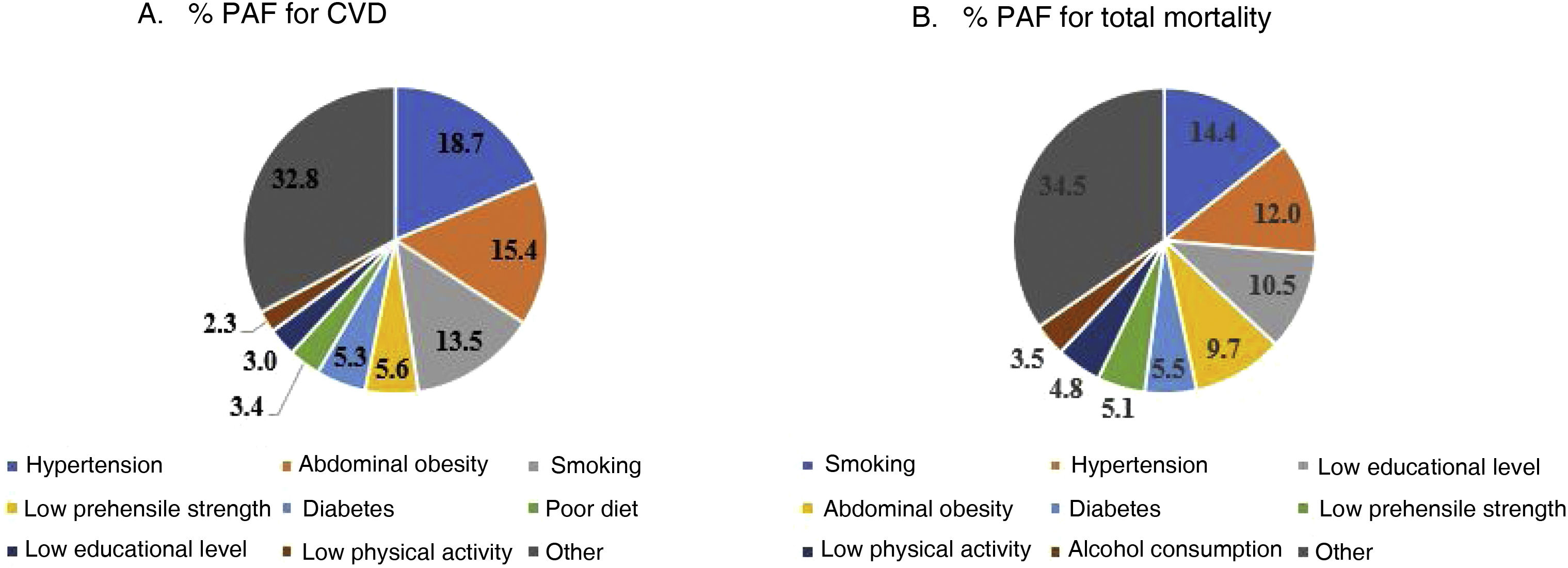

The 12 modifiable risk factors studied contributed to 72% of the PAFs for CVD in the cohort. Metabolic risk factors contributed to 41% of the PAFs, with hypertension (18.7%), abdominal obesity (15.4%), and smoking (13.5%) being the largest, followed by low prehensile strength (5.6%), diabetes (5.3%), poor diet (3.4%), low educational level (3.0%), and low physical activity (2.3%). High non-HDL cholesterol, depression, alcohol consumption, and household air pollution each contributed 2% or less of the PAFs for CVD (Fig. 1A).

Modifiable risk factors made up 69% of the PAFs for death, the most important being smoking (14.4%), hypertension (12.0%), low educational level (10.5%), abdominal obesity (9.7%), diabetes (5.5%), low prehensile strength (5.1%), low physical activity (4.8%), and alcohol consumption (3.5%). Poor diet, depression, household air pollution, and elevated non-HDL cholesterol each contributed 2% or less of the PAFs for death (Fig. 1B).

For myocardial infarction (MI), the five most important risk factors were abdominal obesity (PAF 17.3%), smoking (13.4%), high non-HDL cholesterol (13.3%), hypertension (11.8%), and low prehensile strength (8.3%). The top five risk factors for stroke were high blood pressure (PAF 22.4%), smoking (15.9%), abdominal obesity (10.8%), poor diet (9.9%), and diabetes (5.2%).

In women, the top five risk factors for CVD were hypertension (PAF 17.4%), abdominal obesity (16.2%), smoking (10.4%), diabetes (5.3%), and poor diet (5.2%). In men, hypertension (20.2%), smoking (17.5%), abdominal obesity (12.3%), low prehensile strength (8.3%), and low educational level (5.1%).

In women, the top five risk factors for death were low education (PAF 13.0%), hypertension (12.2%), smoking (10.7%), abdominal obesity (10.1%), and diabetes (5.3%). In men, smoking (17.8%), hypertension (11.9%), low educational level (8.6%), abdominal obesity (8.3%), and low muscle strength (7.7%).

In urban areas, the top five risk factors for CVD were hypertension (PAF 20.7%), abdominal obesity (16.7%), smoking (12.3%), poor diet (7.7%), and low muscle strength (5.8%). In rural areas the top five factors for CVD were hypertension (16.2%), smoking (15.5%), low education (12.5%), abdominal obesity (11.1%), and low prehensile strength (5.4%). In urban areas, the greatest risk factor for death was smoking (PAF 16.5%), followed by hypertension (11.8%), abdominal obesity (11.8%), low education (8.4%), and diabetes (6.0%). In rural areas the main risk factors were hypertension (12.3%), smoking (12.3%), low educational level (9.9%), abdominal obesity (7.5%), and low strength (5.4%).

DiscussionMore than two-thirds of deaths in the region were due to CVD, cancer, or respiratory diseases. Cancer deaths were almost as common as CVD deaths, which may be due to greater control in CVD mortality rates compared to cancer mortality rates over the past decades.5 In addition, in women, cancer overtook CVD as the leading cause of death.

Comparison among the countries in the region included in the study showed modest variations in the incidence of CVD. Age- and sex-adjusted mortality rates varied between the countries to a greater degree than CVD rates, with the highest in Argentina and the lowest in Chile. In all the countries, men experienced higher rates of CVD and deaths compared to women. Mortality was also consistently higher in the rural areas of all the countries.

The incidence of CVD was largely attributed to 12 modifiable risk factors, which together accounted for 72% of the PAFs in the region. As a group, metabolic risk factors were the predominant risk factors for CVD.

The greatest PAFs for CVD risk factors were hypertension, smoking, and abdominal obesity, which collectively accounted for almost 50% of the population-level risk, suggesting that substantial reductions in CVD incidence could be achieved by focusing on controlling these three risk factors. Elevated non-HDL cholesterol contributed only modestly to the PAFs for CVD. However, it was the third leading risk factor for myocardial infarction, a result consistent with previous data suggesting that the risk associated with elevated cholesterol levels is higher for coronary artery disease compared to stroke or heart failure, and therefore statin strategies to lower cholesterol should be maintained as an important health issue and a priority in the region.8 The finding that risk factors for myocardial infarction were associated with abdominal obesity, elevated lipids, and smoking is consistent with previous observations from the INTERHEART Latin American substudy, in which these three risk factors were also associated with the highest population risk.10

Hypertension, smoking, and obesity, in addition to low educational level, were the main risk factors for death in the region. Compared to previous findings from the global PURE study that analysed risk factors by income level across countries in five continents, the contribution to CVD and death from metabolic factors and smoking was similar to that observed in high-income countries, but higher than that observed in other middle-income countries, probably reflecting the epidemiological transition that Latin America is undergoing, where non-communicable diseases are the leading cause of death.8

The shared impact of these risk factors on CVD and premature mortality highlights the need for policies focused on their control, which will have a substantial impact on the health of the South American population. For example, policies aimed at reducing smoking have been well adopted over the past 15 years, resulting in significant reductions in smoking prevalence compared to many other regions of the world.11

Controlling metabolic risk factors remains a challenge for the region. For example, despite high awareness and treatment of hypertension in the Latin American countries we studied, only 40% of treated hypertensives achieve target blood pressure12; therefore, improving metabolic risk factor control will require an adequate understanding of the specific barriers limiting care and implementation of changes aimed at overcoming these barriers.13 In Colombia, we recently demonstrated the effectiveness of a community-level intervention strategy involving the management of metabolic risk factors by non-physician health workers (NPHW), who using simplified management algorithms and counselling programmes, a fixed-dose combination of two antihypertensives plus a statin, administered free of charge by the NPHW, supervised by primary care physicians, plus the support of a family member or friend to improve adherence, allowed us to increase adequate hypertension control from 11.5% to 68.9%. This strategy could be widely applied in the región.14

A consistent finding across all the countries studied was that men had more cardiovascular events and a higher mortality rate than women. This is partly due to the higher burden of metabolic risk factors and the higher prevalence of smoking observed in men compared to women. However, this is notable from previous studies that also reported worse control of cardiovascular risk factors in men.15 Interestingly, we observed that many of the main risk factors for CVD and death are shared between men and women; thus, in both sexes, hypertension, abdominal obesity, and smoking are the leading risk factors for CVD and death. These results favour the widespread implementation of strategies aimed at controlling these risk factors in both men and women. While women had lower rates of death compared to men, the adverse impact of low education was particularly striking in women, in whom it was the main determinant of death. Low education can affect survival through a wide range of effects, including inequality of income, occupation, and access to health and community services.16,17

This study has some potential limitations. Therefore, because our data are based on four countries, the results may not be generalisable to all of Latin America. In addition, within the countries studied, participants were included from only one province in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, although in Colombia participants were recruited from 10 provinces. The study also enrolled a higher proportion of women compared to the general population. However, the fact that data were collected from 100 communities with wide geographic distribution suggests that our study reflects the substantial diversity of the Latin American population. This feature of the PURE study differs from most studies that included individuals from only one or at most a few communities, and almost always from only one country. Ideally, even larger studies than ours should be conducted in Latin America, with representation from several states in each country, as well as the participation of additional countries. However, such large prospective studies are difficult to organise and finance, and are unlikely to be conducted in the foreseeable future.

Although some misclassification of baseline risk factors is possible when they are self-reported, many of the risk factors also derived from or were supplemented by objective measures (e.g., blood pressure, plasma lipid concentration, grip strength, and anthropometry), or when self-reported, but using validated instruments (e.g., physical activity and food frequency questionnaires), allowing for a reduction in this risk.

We have not included information on ambient air pollution, because this requires different approaches and analyses, and as the variation in exposure to this factor is relatively small within a single geographical region such as South America, we believe that our study is not the best setting to study this relationship. It is likely that outdoor air pollution is an important risk factor for CVD, as shown in the publication that includes analysis of the global study data.18

ConclusionsCardiovascular diseases, cancer, and respiratory diseases account for more than two-thirds of deaths in Latin America. Men have consistently higher rates of CVD and mortality than women. A large proportion of CVD and premature deaths could be avoided by controlling metabolic risk factors and smoking, which are major risk factors common to all countries in the region. To our knowledge, this is the largest prospective study to directly compare rates of CVD, death, and the impact of multiple risk factors in Latin America.

Take-home message: a large proportion of CVD and premature deaths in Latin America could be prevented by policies aimed at controlling metabolic risk factors and smoking.

FundingIn Colombia, the PURE study receives partial support from COLCIENCIAS, currently the Ministry of Science and Technology. Grants 6566-04-18062 y 6517-777-58228.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

This article is a summary in Spanish of the article already published in English by Lopez-Jaramillo P, Philip J, Lopez-Lopez JP, Lanas F, Avezum A, Diaz R, et al. Risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in South America: a PURE substudy. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:2841-51. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac113