La nutrición y la salud cardiovascular: una mirada desde el presente hacia el futuro

Más datosNon-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most frequent hepatic disease globally. NAFLD patients are at an increased risk of both liver and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, as well as all-cause death. NAFLD prevalence is rapidly increasing worldwide and, thus, there is an urgent need for health policies to tackle its development and complications. Currently, since there is no drug therapy officially indicated for this disease, lifestyle interventions remain the first-line therapeutic option.

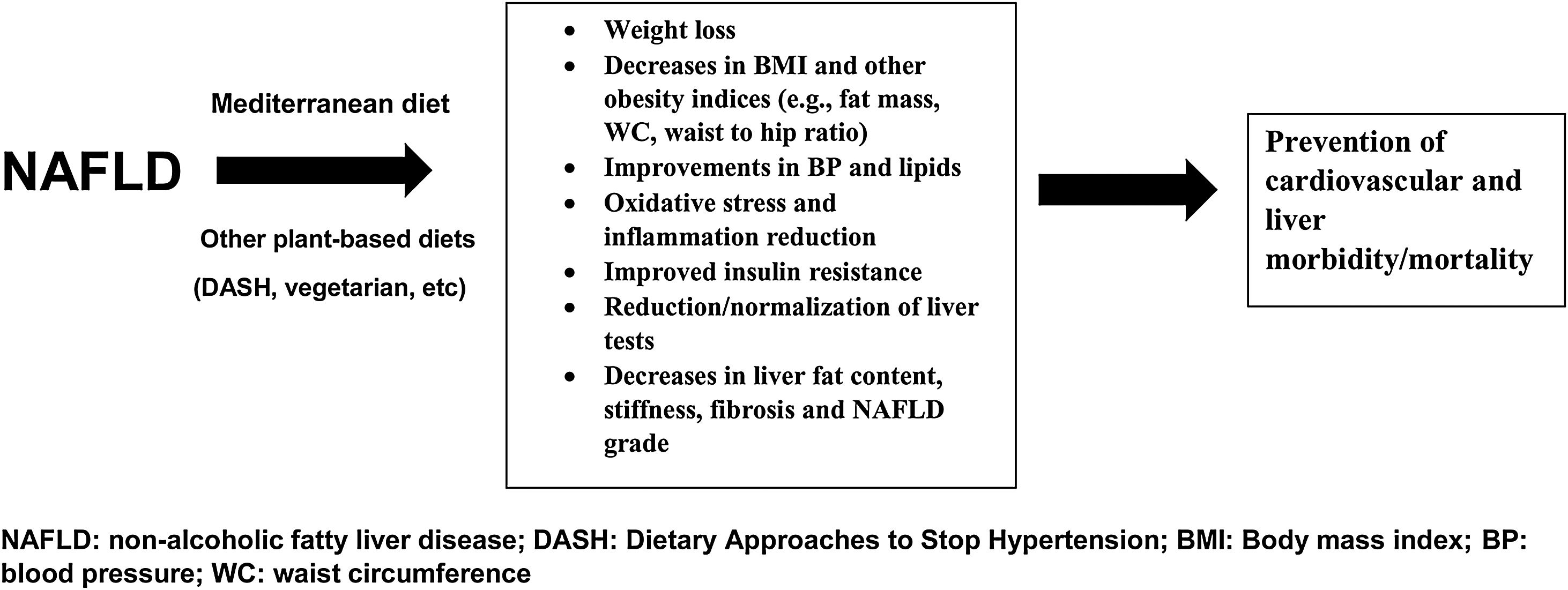

In the present narrative review, we discuss the effects of certain dietary patterns on NAFLD incidence and progression. The Mediterranean diet is regarded as the diet of choice for the prevention/treatment of NAFLD and its complications, based on the available evidence. Other plant-based dietary patterns (poor in saturated fat, refined carbohydrates, red and processed meats) are also beneficial [i.e., Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and vegetarian/vegan diets], whereas more data are needed to establish the role of ketogenic, intermittent fasting and paleo diets in NAFLD.

Nevertheless, there is no “one-size-fits-all” dietary intervention for NAFLD management. Clinicians should discuss with their patients and define the diet that each individual prefers and is able to implement in his/her daily life.

La enfermedad de hígado graso no alcohólico (EHGNA) es la enfermedad hepática más frecuente a nivel global. Los pacientes de EHGNA tienen un riesgo incrementado de morbilidad y mortalidad hepática y cardiovascular, y muerte por cualquier causa. La prevalencia de EHGNA se está incrementando rápidamente a nivel mundial, y por tanto existe una necesidad urgente de políticas sanitarias para afrontar su desarrollo y complicaciones. Actualmente, dado que no existe ninguna terapia farmacológica indicada de manera oficial para esta enfermedad, las intervenciones sobre el estilo de vida siguen siendo la opción terapéutica de primera línea.

En la revisión de la narrativa actual debatimos los efectos de ciertos patrones alimentarios en la incidencia y progresión de EHGNA. La dieta mediterránea se considera la dieta de elección para la prevención/tratamiento de EHGNA y sus complicaciones, sobre la base de la evidencia disponible. Otros patrones alimentarios basados en plantas (bajos en grasas saturadas, hidratos de carbono refinados, carnes rojas y procesadas) son también beneficiosos —es decir, DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [Enfoques alimentarios para detener la hipertensión]) y dietas vegetarianas/veganas—, aunque se necesitan más datos para establecer el papel de las dietas cetogénicas, de ayuno intermitente y paleo en la EHGNA.

Sin embargo, no existe una intervención alimentaria «universal» para el manejo de EHGNA. Los clínicos deberán debatir con sus pacientes y definir la dieta que prefiera cada individuo, y que este pueda introducir en su vida diaria.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the major cause of hepatic disease worldwide, affecting over 25% of the general population.1 The prevalence of NAFLD is further increased in obese individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).2 Histologically, NAFLD begins as simple steatosis (i.e., >5% liver fat accumulation without inflammation) and can progress to the more severe form of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (with inflammation, necrosis, ballooning and fibrosis), potentially leading to liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and end-stage liver disease.3 Apart from liver morbidity and mortality, NAFLD/NASH patients have also an increased cardiovascular (CV) risk, with more patients dying from a CV event than a liver-related cause.3

Taken into consideration that the epidemic of obesity and T2D is constantly increasing globally, NAFLD prevalence is also increasing proportionately.2 Therefore, there is an urgent need to tackle this tremendous clinical and economic burden by preventing and/or treating NAFLD/NASH. Although there are some drugs (e.g., hypolipidemic and antidiabetic) that have been reported to improve the biochemical and histological features of NAFLD/NASH,4–7 there is currently no drug therapy officially approved for this disease and thus, lifestyle interventions remain the first-line therapeutic option. Nutrition research is now focusing on healthy dietary patterns (and not on single nutrients or specific foods) to identify the optimal diets for chronic disease prevention.8 In the present narrative review, we discuss the effects of certain dietary patterns on NAFLD/NASH incidence and progression.

Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) and NAFLDMedDiet is the most widely studied dietary pattern in scientific literature, found to exert, apart from weight loss, several other health benefits such as improvements in oxidative stress and inflammatory markers, insulin sensitivity, glucose and lipid metabolism, endothelial and antithrombotic function.9–11 These beneficial effects of the MedDiet have been largely attributed to certain dietary components, including monounsaturated fatty acids (mainly olive oil), polyunsaturated fatty acids (from nuts, seed and fish), as well as plant-based foods (such as vegetables, legumes and fruits). A higher adherence to the MedDiet has been related to lower risks of all-cause mortality, CV morbidity and death, metabolic diseases and cancer.9 MedDiet is considered for the prevention of cardiometabolic and degenerative diseases, focusing on its beneficial impact as a holistic dietary approach.12 In this context, it has been shown that adherence to the MedDiet can lower the risk of developing NAFLD.13

Several cross-sectional and randomized clinical trials have been conducted to test the effects of MedDiet in NAFLD/NASH patients, as reviewed elsewhere.14,15 In these trials, MedDiet was reported to reduce weight, BMI, BP, oxidative stress, inflammation, insulin resistance, fasting glucose and lipids, as well as NAFLD score, intrahepatic fat content, liver tests, hepatic steatosis, stiffness and fibrosis and NAFLD severity and progression.16,17 Of note, the hepatometabolic benefits induced by the MedDiet are independent of weight loss.18 In meta-analyses involving NAFLD patients, implementation of the MedDiet was shown to improve weight, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, liver tests, steatosis and NAFLD severity indices, as well as to decrease overall mortality and morbidity.15,19–22

Based on the above, MedDiet is recommended in individuals with NAFLD/NASH, since it can improve both liver steatosis and several CV risk factors, thus also protecting from CV morbidity/mortality.23 Indeed, current guidelines, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)24 and the joint recommendation from the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO),25 strongly support the implementation of MedDiet in NAFLD/NASH patients.

Overall, the MedDiet is superior to other diets in preventing/treating NAFLD/NASH, as well as MetS and its components, T2D and CVD.18 Furthermore, MedDiet is easier to follow and has greater scientific evidence for cardiometabolic benefits compared with other dietary patterns. Therefore, it is recommended as the diet of choice for the prevention/treatment of NAFLD/NASH and its complications.

Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and NAFLDDASH diet has been shown to significantly reduce body weight, BP, LDL-C, total cholesterol and HbA1c, as well as protect against CVD and T2D incidence, thus representing an attractive option for overweight/obese patients.26,27 There is also some evidence on DASH diet-induced benefits in NAFLD patients.28 In this context, in a cross-sectional analysis of the Guangzhou Nutrition and Health Study (a population-based cohort study, involving 3051 participants), adherence to the DASH diet (defined by higher DASH diet score) was independently associated with a significantly lower prevalence of NAFLD, as well as with reduced levels of inflammation, insulin resistance and BMI.29 A similar inverse relationship between the DASH diet and the risk of NAFLD was reported in a case–control study with 102 NAFLD patients (diagnosed by transient elastography) and 204 controls,30 as well as in a nested case–control analysis of the Multiethnic Cohort (MEC) [n=2959 NAFLD cases (509 with cirrhosis) and 29,292 controls].31 In the latter study, the inverse association was even greater for NAFLD patients with than those without cirrhosis.31 Apart from NAFLD risk, DASH score has also been inversely associated with liver fat content (measured by MRI) in a cross-sectional study of 136 non-diabetic non-smokers individuals.32

In a randomized controlled trial (n=60 overweight/obese NAFLD patients, diagnosed by ultrasonography and increased ALT levels), implementation of the DASH diet for 8 weeks was reported to significantly improve weight, BMI, ALT, insulin resistance and TG, as well as markers of inflammation and oxidative stress compared with the control diet.33

Overall, the DASH diet can beneficially affect several cardiometabolic risk factors, as well as protect against CVD and T2D development. Further data is needed to clarify its efficacy in NAFLD/NASH biochemical and histological features.

Ketogenic diet and NAFLDLow-carbohydrate ketogenic diets (KD) have been reported to significantly reduce intrahepatic TG content within 48h in obese individuals.34 Apart from weight loss, KD may decrease insulin levels and lipogenesis, as well as increase fatty acid oxidation (due to their very low carbohydrate content), and even beneficially affect liver pathology (due to the role of ketone bodies as moderators of fibrosis and inflammation).35 Reduced hepatic insulin resistance and increased hepatic mitochondrial redox state, promoting the net hydrolysis of intrahepatic TG and thus ketogenesis from the resulting fatty acids, have also been implicated in KD-related NAFLD reversal.36

In a pilot, open-label, randomized controlled trial involving 18 obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome, KD for 12 weeks was superior in lowering ALT and AST, and improving liver ultrasound features compared with the control group (receiving Essentiale plus Yasmin, i.e., conventional drug treatment).37 Furthermore, a very low-calorie KD led to greater reductions in body weight, visceral adipose tissue and liver fat content compared with a standard low-calorie diet in 39 obese patients after 2 months of intervention.38 The authors suggested that this rapid mobilization of hepatic fat and weight loss induced by KD could serve as an effective alternative for NAFLD treatment.38 It has also been reported that obese men may experience larger benefits (in terms of body weight and liver tests reduction) with very low-carbohydrate KD compared with pre-menopausal women; these differences are lessened after menopause.39

The implementation of a hypocaloric KD for 6.5 months was shown to significantly improve body weight, systolic BP, TG, ALT, AST and fibrosis score in 38 patients with NASH (diagnosed by liver biopsy, transient elastography, magnetic resonance elastography or liver test abnormalities).40 However, long-term maintenance on a KD could lead to increases in liver tests and induce lipid and glucose disorders (due to their high-fat content) and thus increased vigilance and monitoring is encouraged in patients on such a diet.41,42 Overall, further clinical evidence is needed to establish the role (and ideal duration) of KD in NAFLD prevention and treatment.

Intermittent fasting diet and NAFLDIn an open-label randomized controlled trial, 74 patients with NAFLD (diagnosed by ultrasound, CT, MRI or transient elastography) were assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to intermittent calorie restriction diet (the 5:2 diet), low-carb high-fat diet (LCHF) or general lifestyle advice (standard of care; SoC) and followed-up for 12 weeks.43 Of note, participants in the 5:2 group were instructed to consume 600kcal/day for men and 6500kcal/day for women on 2 non-consecutive days per week. Both 5:2 and LCHF diets were superior to SoC treatment in terms of body weight and liver steatosis reduction (measured by MRS), leading to similar improvements.43 Furthermore, the 5:2 diet (but not the LCHF diet) also reduced liver stiffness and LDL-C and was better tolerated than LCHF.43

Periodic fasting was also shown to significantly reduce FLI in 697 individuals with or without T2D in a prospective observational trial; the magnitude of this benefit was greater in T2D patients.44 Body weight, BMI, waist circumference, fasting glucose, HbA1c and liver enzymes were also significantly decreased after periodic fasting. FLI improvement correlated with the number of fasting days and the extent of BMI reduction.44 After fasting, almost half of the participants with baseline FLI ≥60 (representing the threshold for NAFLD) shifted to a lower category of FLI risk, thus suggesting liver disease reversion. It should be noted that periodic fasting was implemented as it follows: an initial phase of a low-calorie transition day (600kcal/day mono-diet consisting of vegetables, fruits, oat or rice), followed by the fasting period (250mL vegetable broth or fruit juice at midday, 250mL vegetable broth in the evening and 20g honey optionally), and then a stepwise reintroduction of food (lacto-ovo-vegetarian food increasing from 800 to 1800kcal/day over at least 3 days).44 The participants were advised to drink ≥2L of water/day.

Alternate-day fasting was reported to significantly decrease insulin resistance, total cholesterol, LDL-C, liver weight and ALT in animal models of MetS.45 Similarly, significant reductions in body weight, fat mass, total cholesterol and TG were observed among 271 patients with NAFLD (assessed by ultrasound) following alternate-day fasting or time-restricted feeding for 12 weeks.46 In another randomized clinical trial, involving 43 patients with NAFLD (defined by elevated liver tests), alternate-day calorie restriction for 8 weeks significantly lowered BMI, ALT, liver steatosis grades and fibrosis scores compared with habitual diet.47 Alternate-day diet was well-tolerated with good adherence rate throughout the study.47

There is some evidence that Ramadan fasting can improve NAFLD features. In this context, among 83 NAFLD patients, body weight, BMI, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and body fat percentage were significantly reduced in those who performed Ramadan fasting compared with the non-fasting group.48 Significant improvements in liver tests, steatosis, inflammatory markers, insulin sensitivity and NAFLD severity scores have also been reported following Ramadan fasting in NAFLD/NASH patients.49,50

A recent meta-analysis, including 6 studies (4 used Ramadan fasting and 2 used alternate-day fasting) with a total of 417 NAFLD patients, further supports the beneficial effects of intermittent fasting on body weight, BMI and liver tests.51 The authors concluded that long-term safety and feasibility of intermittent fasting should be evaluated in the future.51

Overall, further studies, including a control group and long-term follow-up, are needed to establish the positive effects of different types of intermittent fasting (e.g., 5:2, alternate-day, periodic and Ramadan fasting, as well as 16/8 involving 16h fasting every day) on NAFLD development and progression.

Vegetarian (vegan) diet and NAFLDA cross-sectional study, involving 2127 nonvegetarians and 1273 vegetarians (all healthy volunteers), showed that the odds for fatty liver (measured by ultrasound) were significantly lower (by 21%) in vegetarians compared with nonvegetarians, even after adjustment for gender, age, smoking, alcohol intake and education.52 However, BMI slightly attenuated this association. Furthermore, nonvegetarians had a more severe fibrosis score than vegetarians.52 The authors suggested that the observed liver benefits from the vegetarian diet may be attributed to its rich content in polyphenols which can decrease inflammation, oxidative stress and insulin resistance, thereby suppressing NAFLD progression.52

A previous analysis of data from the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study (n=892 participants) reported that the consumption of a vegetarian diet was associated with lower BMI, fasting glucose, insulin resistance, total cholesterol and LDL-C, as well as a lower (by 57%) risk of fatty liver [assessed by CT].53

In a 3-month randomized clinical trial with 75 overweight/obese NAFLD patients, lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet (based on eliminating poultry, meat and fish, but including eggs and dairy products) was compared with a standard weight-loss diet (based on the standard food pyramid, free in all sources of food).54 Patients following the lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet showed greater improvements in body weight, BMI, waist circumference, ALT, fasting glucose, insulin resistance, TG, LDL-C and systolic BP, as well as a greater alleviation of NAFLD grade (in ultrasonography) compared with those on the weight-loss diet.54

In another prospective, pilot study, 26 NAFLD patients followed a strict vegan diet (excluding all animal products) for 6 months.55 At the end of the study, liver enzymes (ALT, AST, GGT) were significantly improved and even normalized in 20/26 patients. Of note, body weight and BMI were also significantly decreased but this reduction did not correlate with the normalization of liver tests, thus highlighting the fact that a vegan diet can beneficially affect liver function, irrespective of weight loss.55

A previous cross-sectional, retrospective study (n=615) compared NAFLD prevalence (measured by ultrasound) between Buddhist priests (being vegetarians) and controls (matched for age, gender, BMI and presence/absence of MetS).56 No difference was observed in NAFLD prevalence between the 2 groups, with Buddhist priests also having higher liver tests (ALT, AST) and TG levels.56 The authors concluded that “The vegetarian diet does not protect against NAFLD”, however such a statement seems too strong for such limited data and cannot be supported by these results.

Overall, healthy plant-based diets (as the vegetarian) were related to a lower NAFLD risk (defined by FLI) and more favorable liver tests as shown in cross-sectional study using data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).57 Such dietary patterns (including Mediterranean, DASH and vegetarian diets) have been proposed for NAFLD/NASH management.58 Further research should focus on the effects of the vegetarian diet and its subtypes (e.g., lacto-, ovo-, lacto+ovo-, pescatarian, vegan) on liver biochemistry and histology in NAFLD/NASH patients.

Paleo diet and NAFLDData on the effects of the paleo(lithic)-type diet (also known as the Hunter-Gatherer diet) in NAFLD/NASH patients is lacking. A single-blinded, randomized controlled, pilot study (n=32 individuals with ≥2 MetS features) found that a 2-week paleo diet significantly lowered body weight, BP, total cholesterol and TG, as well as increased HDL-C.59 These effects could also be beneficial in NAFLD/NASH patients. Indeed, the paleolithic diet (based on vegetables, fruits, vegetables, nuts, roots and organ meats) has been reported to improve dyslipidemia, hypertension, body weight, waist circumference, fasting glucose and insulin resistance.60,61 In another randomized study, involving 70 healthy, obese, postmenopausal women, liver fat (assessed by proton MRS) was significantly lower in women following a paleo diet for 6 months compared with those on a low-fat diet.62 However, this difference in liver fat reduction lost its statistical significance at 24 months. Furthermore, the consumption of a paleo diet for 5 weeks led to a significant decrease in liver TG content (measured by proton MRS), as well as improvements in BMI, fasting glucose, BP, lipids, waist and hip circumference, waist/hip ratio and abdominal sagittal diameter in 10 healthy postmenopausal women.63 Similarly, body weight and fat mass, as well as liver fat (assessed by MRS) were significantly reduced in 32 overweight-obese T2D patients that followed a paleolithic diet (with or without exercise) for 12 weeks.64 Adipose and peripheral tissue (but not hepatic) insulin sensitivity was also improved.

Overall, the paleo diet seems a promising asset in preventing/treating NAFLD but well-designed, long-term, clinical trials are needed to elucidate the impact of this dietary pattern on biochemical and/or histological NAFLD/NASH parameters.

Table 1 summarizes the abovementioned beneficial effects of different dietary patterns on cardiometabolic and liver parameters observed in NAFLD patients. These diet-induced benefits could prevent/minimize CVD and liver morbidity/mortality (Fig. 1).

Beneficial effects of different dietary patterns on cardiometabolic and liver parameters observed in NAFLD patients.

| Dietary pattern | Beneficial effects |

|---|---|

| Mediterranean diet | Body weightBMIBPOxidative stressInflammationInsulin resistanceFasting glucoseFasting lipidsNAFLD scoreIntrahepatic fat contentLiver testsHepatic steatosisLiver stiffnessHepatic fibrosisNAFLD severity |

| Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) | Body weightBMIInflammationInsulin resistanceFasting lipidsFasting TGALTLiver fat content |

| Vegetarian diet | Body weightBMIWaist circumferenceSystolic BPFasting glucoseInsulin resistanceTG, LDL-CALTLiver fatNAFLD grade |

| Ketogenic diet | Body weightSystolic BPFasting TGLiver tests (ALT, AST)Liver fibrosis scoreHepatic insulin resistance |

| Intermittent fasting diet | Body weightBMIBody fat massInflammationInsulin sensitivityFasting total cholesterol and TGLiver tests (ALT, AST)Liver steatosisHepatic stiffnessLiver fibrosisNAFLD severity scores |

| Paleo diet | Data in NAFLD patients are missingBMIBody fat massWaist and hip circumferenceWaist/hip ratioBPInsulin resistanceFasting glucoseFasting lipidsLiver fat |

BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure; TG: triglycerides; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate transaminase; NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

It should be noted that recently, have proposed a new definition of fatty liver has been proposed by several international expert panels, namely metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD).65

ConclusionsCurrently, diet-induced weight loss is regarded as the first therapeutic approach in NAFLD/NASH to resolve steatosis and reverse fibrosis. Plant-based dietary patterns, poor in saturated fat, refined carbohydrates, red and processed meats, are preferred, including the Mediterranean, DASH and vegetarian/vegan diets.58 Such dietary patterns have previously been recommended for the prevention and treatment of MetS.66 Since NAFLD is considered as the hepatic manifestation of MetS,5 it follows that these diets can also be beneficial for NAFLD/NASH patients. MedDiet is regarded as the diet of choice for the prevention/treatment of NAFLD/NASH and its complications, based on the available evidence. Future well-designed clinical trials will establish the role of each of these dietary patterns, as well as of KD, intermittent fasting and paleo diets in NAFLD/NASH prevention and treatment.

Nevertheless, since psychological, social, cultural and economic factors, as well as co-morbidities may differ, there is no “one-size-fits-all” dietary intervention for NAFLD management. Clinicians should discuss the different dietary patterns with their patients and define the diet that each individual prefers and is able to implement in his/her daily life.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the current research was conducted independently, in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

NK has given talks, attended conferences and participated in trials sponsored by Angelini, Astra Zeneca, Bausch Health, Boehringer Ingelheim, Elpen, Mylan, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and Servier.

APS is currently Vice President of Romanian National Diabetes Committee, and she has given lectures, received honoraria and research support, and participated in conferences, advisory boards, and clinical trials sponsored by many pharmaceutical companies, including AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, and Sanofi.

MR is a full-time Professor of Internal Medicine at University of Palermo, Italy, and currently Section Editor in Chief for the International Journal of Molecular Sciences and Medical Director, Novo Nordisk in Eastern Europe; he has given lectures, received honoraria and research support, and participated in conferences, advisory boards, and clinical trials sponsored by many pharmaceutical companies including Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Kowa, Eli Lilly, Meda, Mylan, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, Sanofi and Servier.

None of the above had any role in this article, which has been written independently, without any financial or professional help, and reflects only the authors’ opinion, without any role of the industry.