Familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) is a genetic entity with autosomal recessive inheritance. Mutations in genes (such as APOC2, APOAV, LMF-1, GPIHBP-1) that code for proteins that regulate the maturation, transport, or polymerization of lipoprotein lipase-1 are the most common causes, but not the only ones. The objective of this study was to report the first documented case in Ecuador.

Clinical caseA 38-year-old man presented with chronic hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, pancreatic atrophy, and severe hypertriglyceridemia refractory to treatment. A molecular analysis was performed by next generation sequencing that determined a deficiency of Lipoprotein Lipase OMIM #238600 in homozygosis. Genetic confirmation is necessary in order to establish the etiology of HTGS for an adequate management of this pathology.

El síndrome de quilomicronemia familiar (SQF) es una entidad genética de herencia autosómica recesiva. Las mutaciones en genes (como APOC2, APOAV, LMF-1, GPIHBP-1) que codifican para proteínas que regulan la maduración, transporte o polimerización de lipoproteína lipasa-1 son las causas más comunes, pero no las únicas. El objetivo de este estudio fue reportar el primer caso documentado en el Ecuador.

Caso clínicoHombre de 38 años que presentó hepatoesplenomegalia crónica, plaquetopenia, atrofia pancreática e hipertrigliceridemia severa refractaria al tratamiento. Se realizó un análisis molecular por secuenciación de nueva generación que determinó una deficiencia de Lipoprotein Lipasa OMIM #238600 en homocigosis. La confirmación genética es necesaria a fin de poder establecer la etiología de HTGS para un adecuado manejo de esta patología.

Familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) is a chronic metabolic disease characterised by marked elevation of triglycerides and chylomicrons in the blood.1 FCS is genetic in origin, autosomal recessive in inheritance and predisposes to high mortality from pancreatitis.2,3

FCS is considered a rare pathology worldwide and underestimated in Ecuador.2 The global prevalence is 1 per 1,000,000 inhabitants, and in highly complex specialised centres, up to 1 per 300,000 inhabitants.3

FCS is identified in childhood due to severe hypertriglyceridaemia (triglycerides>10mmol/l) and recurrent acute pancreatitis.2,4 Clinical features include lack of response to conventional triglyceride-lowering treatments plus repeated episodes of abdominal pain, eruptive cutaneous xanthomatosis, lipidaemia retinalis, hepatosplenomegaly and pancreatitis.3 In addition, they have impaired physical, emotional and cognitive status that impacts on education, employment status and quality of life.5

The diagnosis of FCS is made with a genetic test.3 Pathogenic bi-allelic mutations in the lipoprotein lipase (LPL), apolipoprotein c2 (APOC2), glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchored high density lipoprotein binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1) or lipase maturation factor 1 (LMF-1) genes confirm the disease. Six patients were reported in whom autoantibodies against LPL or GPIHBP1 proteins were evaluated, without familial chylomicronemia and responsive to immunosuppressants.1

The treatment is aimed at reducing triglyceride from the intestine in the form of chylomicron. Volanesorsen for FCS6 is an antisense oligonucleotide to decrease the production of apoprotein C-III. ApoC-III also appears to be an inhibitor of LPL-1 and especially an apoE antagonist. Side effects include trombocitopenia7 and its use is contraindicated in patients with platelet counts below 140,000 (units). No other effective and safe pharmacotherapeutic alternatives have been reported. Surgical strategies to reduce pancreatitis such as bariatric surgery8 and splenectomy have been extreme alternatives that are not even recommended due to lack of evidence.9 The aim of this report was to describe the symptomatology and confirmed diagnosis of FCS that presented atypically.

Clinical case reportA 38-year-old man with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism; family history highlighted the sister, who died at the age of 25 years due to necrotising pancreatitis.

Elevated triglycerides (560mg/dl) were recorded for the first time at the age of 27 years and he had several hospitalisations for hypertriglyceridaemia, with levels reaching up to 3000mg/dl, without presenting pancreatitis or specific diagnosis on hospital discharges. The patient had a body mass index (BMI) of 23kg/m2 and stable vital signs. There were no relevant findings during the rest of the physical examination.

An abdominal ultrasound was performed, which identified a heterogeneous liver with a micronodular appearance and splenomegaly. It was defined as chronic liver disease.

Initial laboratory studies revealed high triglyceride levels of 890mg/dl (Fig. 1), total cholesterol of 154mg/dl, LDL cholesterol of 16mg/dl, HDL cholesterol of 12mg/dl and 115 000 platelets per microlitre (μl).

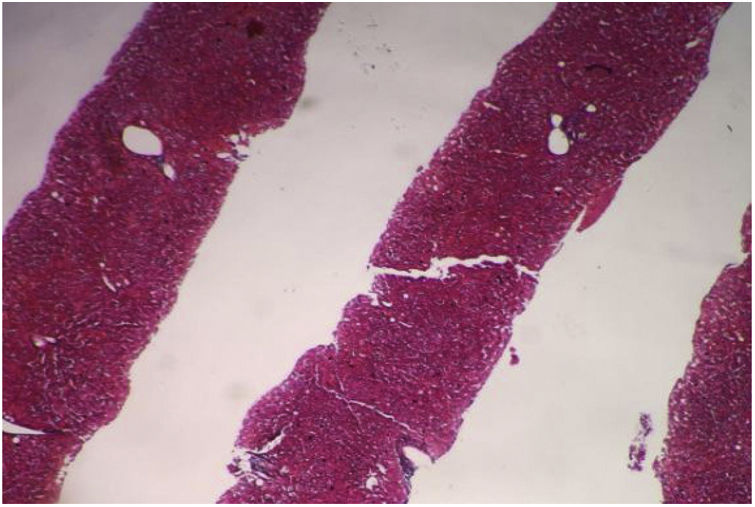

Contrast abdominal CT scan identified an atrophic pancreas, enlarged spleen (hepatosplenomegaly), with no free fluid in the abdominal cavity. It was decided to perform percutaneous ultrasound-guided liver biopsy for assessment of fibrosis due to discordance between imaging studies (Fig. 2).

The histopathological study identified the liver parenchyma with preserved general structure: eight portal spaces were identified, between complete and incomplete. The portal spaces and ductal structures were unaltered, and the vascular structures were not dilated. The hepatocytes retained their usual radial arrangement, the central veins were unchanged and no fibrosis was identified.

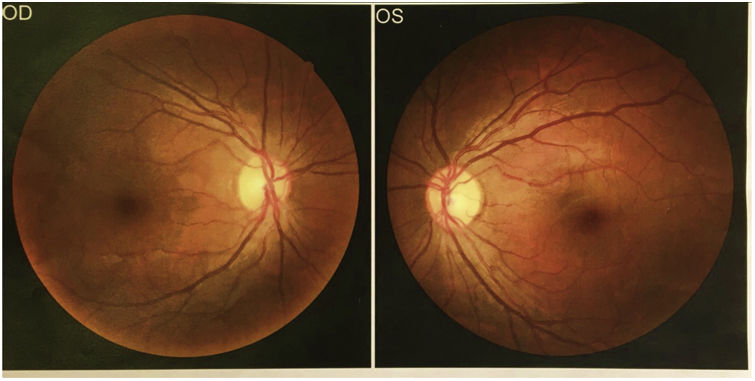

Ophthalmology was consulted for fundus examination, which did not identify retinal lipidaemia (Fig. 3).

Due to the history of multiple hospital admissions for hypertriglyceridaemia and the refractory response to lipid-lowering treatment, a presumptive diagnosis of FCS was made, although the patient denied consanguinity between the parents.

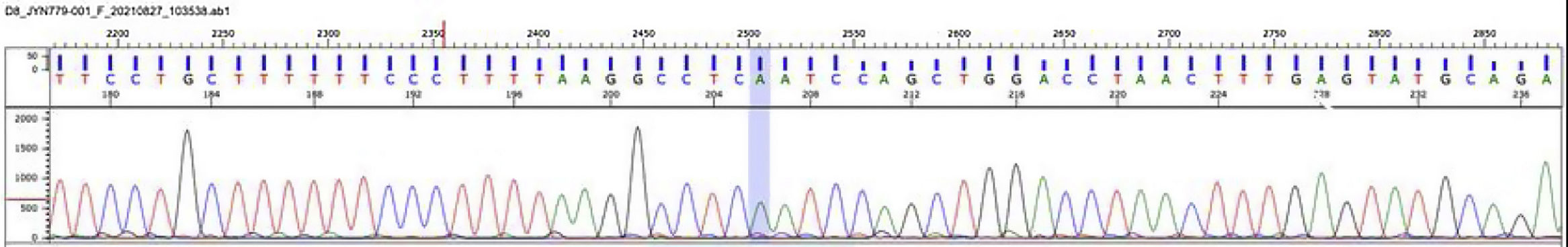

Molecular study was performed by next-generation sequencing of the LPL, APOA5, APOC2, GPIHBP1 and LMF1 genes. The analysis identified a homozygous mutation in the LPL gene (lipoprotein lipase, OMIM* 609708): c.547G>A (pAsp183Asn) [dbSNPrs118204064] (Fig. 4). This mutation is considered pathogenic and has been found to be responsible for lipoprotein lipase deficiency.10

Lipoprotein lipase deficiency, electropherogram: molecular study by next generation sequencing of LPL, APOA5, APOC2, GPIHBP1 and LMF-1 genes. The analysis identified a homozygous mutation in the LPL gene (lipoprotein lipase, OMIM* 609708): c.547G>A (pAsp183Asn) [dbSNPrs118204064].

Source: Mendelics Analise Genomica S, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Treatment was started 4 years ago with metformin, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and insulin, gemfibrozil, statins and fenofibric acid. In addition to low-fat diet and adequate control of comorbidities. Current laboratory studies of triglycerides were similar to the initial ones due to the lack of effective and safe therapy.

DiscussionThis study reports the first case of FCS in Ecuador, which is one of the few described worldwide.2,5 The patient presented hypertriglyceridaemia and splenic involvement without pancreatitis, an atypical symptomatology. Genetic analysis found a homozygous mutation in the LPL gene.

Several cases of FCS with other mutations and characterised by the presence of pancreatitis have been described. Truninger et al.11 described two siblings in Switzerland who had FCS due to compound heterozygous mutations in the LPL gene; both had recurrent acute pancreatitis. Ahmad and Wilson12 reported a paediatric patient in the USA with FCS who developed acute pancreatitis, had mutations in the GPHBP1 gene and responded well to an extremely low-fat diet rich in medium-chain triglycerides. Zhang et al.13 reported two siblings from China who had signs of FCS in the first weeks of life and had mutations in the LPL gene; plasma lipid levels decreased after dietary interventions. Pinilla-Monsalve et al.14 reported a 50 year-old Colombian patient with FCS who had mutations in the APOC gene and a medical history of severe and recurrent episodes of pancreatitis, with no response to the use of pharmacological agents. Ueda et al.15 studied three siblings from the USA with FCS who had mutations in the LPL gene and onset of symptoms in adolescence, presented with recurrent pancreatitis and responded to a lipid-restricted diet. Cefalù et al.16 reported an Italian patient with FCS with symptom onset before the age of 10 years, identified mutations in the LPL gene and also had recurrent pancreatitis. This patient had a good response to treatment with lomitapide.

FCS should be suspected with triglyceride values greater than 885mg/dl. It is proposed to use the Moulin score based on clinical characteristics, which with values greater than 10 indicates a high probability of this pathology.3 FCS should be differentiated from multifactorial chylomicronemia syndrome (MCHS), which also presents with severe hypertriglyceridaemia and pancreatitis but differs in the age of presentation. The former usually appears in childhood or adolescence, while the latter occurs more frequently in adulthood. MQS may also be accompanied by other metabolic pathologies, such as diabetes mellitus and hepatic steatosis.17 Heterogeneity in the occurrence of pancreatitis and lack of awareness of the disease contribute to inadequate care.2,18

Assessment of the reported patient was atypical, and long-term follow-up for future complications remains to be investigated. Multidisciplinary management and timely detection with genetic analysis in the face of dyslipidaemia refractory to conventional treatment allowed the diagnosis of the first case of FCS reported in Ecuador. The interdisciplinary approach and molecular diagnosis by identifying mutations in candidate genes would allow appropriate management with available therapeutic options.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

![Lipoprotein lipase deficiency, electropherogram: molecular study by next generation sequencing of LPL, APOA5, APOC2, GPIHBP1 and LMF-1 genes. The analysis identified a homozygous mutation in the LPL gene (lipoprotein lipase, OMIM* 609708): c.547G>A (pAsp183Asn) [dbSNPrs118204064]. Source: Mendelics Analise Genomica S, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Lipoprotein lipase deficiency, electropherogram: molecular study by next generation sequencing of LPL, APOA5, APOC2, GPIHBP1 and LMF-1 genes. The analysis identified a homozygous mutation in the LPL gene (lipoprotein lipase, OMIM* 609708): c.547G>A (pAsp183Asn) [dbSNPrs118204064]. Source: Mendelics Analise Genomica S, Sao Paulo, Brazil.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/25299123/0000003400000006/v4_202302222005/S2529912322000699/v4_202302222005/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)