The complex humanitarian crisis (CHC) in Venezuela is characterized by food insecurity, hyperinflation, insufficient basic services, and the collapse of the healthcare system. The evolution of the epidemiology of cardiometabolic risk factors in this context is unknown.

AimTo compile the last 20 years evidence on the prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in adults of Venezuela in the context of the CHC.

MethodsA comprehensive literature review of population-based studies of adults in Venezuela from 2000 to 2020.

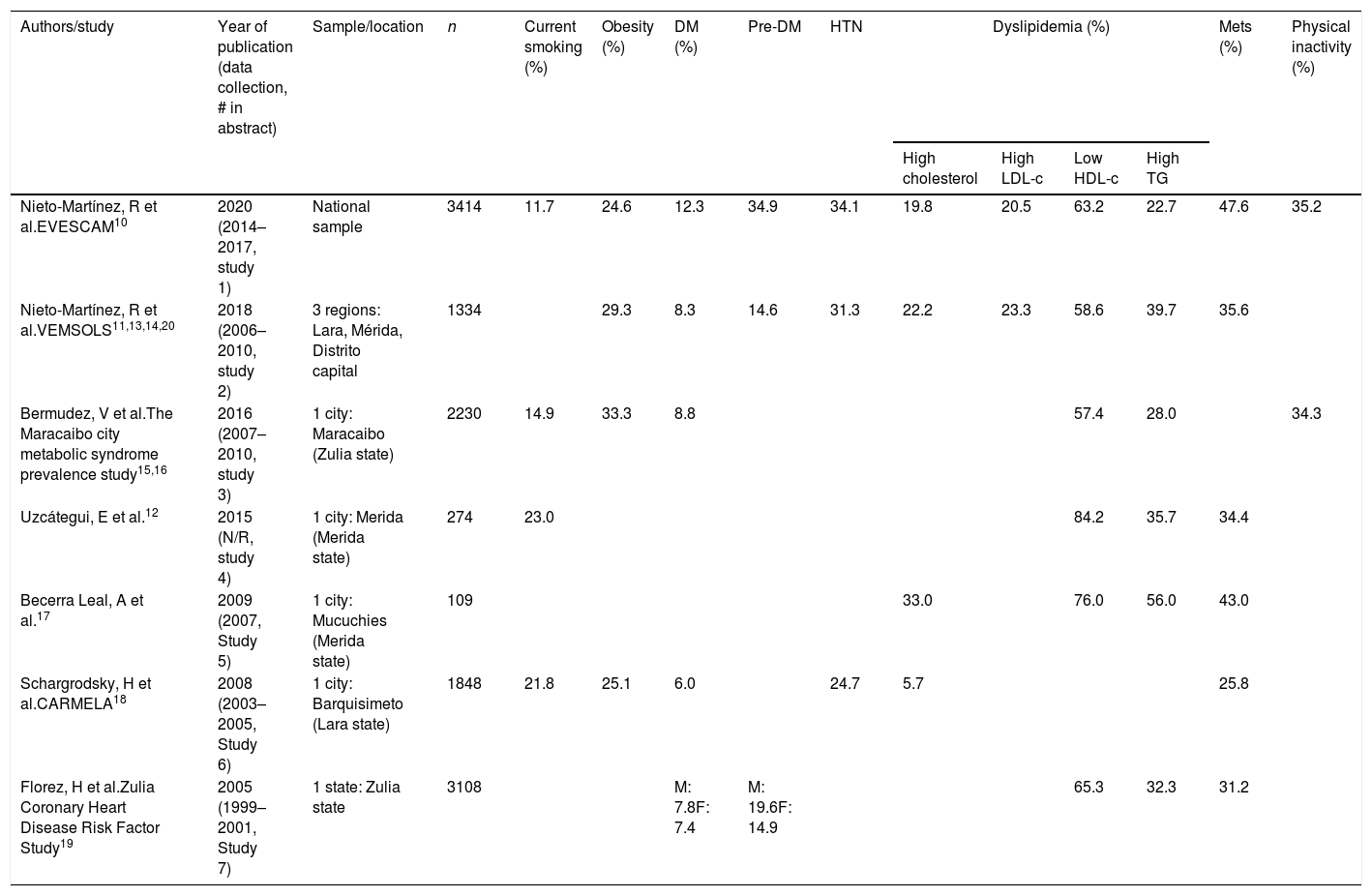

ResultsSeven studies (National EVESCAM 2014–2017, 3 regions VEMSOLS 2006–2010, Maracaibo city 2007–2010, Merida city 2015, Mucuchies city 2009, Barquisimeto city CARMELA 2003–2005, and Zulia state 1999–2001) with samples sizes ranging from 109 to 3414 subjects were included. Over time, apparent decrease was observed in smoking from 21.8% (2003–2005) to 11.7% (2014–2017) and for obesity from 33.3% (2007–2010) to 24.6% (2014–2017). In contrast, there was an apparent increase in diabetes from 6% (2003–2005) to 12.3% (2014–2017), prediabetes 14.6% (2006–2010) to 34.9% (2014–2017), and hypertension 24.7% (2003–2005) to 34.1% (2014–2017). The most prevalent dyslipidemia – a low HDL-cholesterol – remained between 65.3% (1999–2001) and 63.2% (2014–2017). From 2006–2010 to 2014–2017, the high total cholesterol (22.2% vs 19.8%, respectively) and high LDL-cholesterol (23.3% vs 20.5%, respectively) remained similar, but high triglycerides decreased (39.7% vs 22.7%, respectively). Using the same definition across all the studies, metabolic syndrome prevalence increased from 35.6% (2006–2010) to 47.6% (2014–2017). Insufficient physical activity remained steady from 2007–2010 (34.3%) to 2014–2017 (35.2%).

ConclusionChanges in the prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in Venezuela are heterogeneous and can be affected by various social determinants of health. Though the Venezuelan healthcare system has not successfully adapted, the dynamics and repercussions of the CHC on population-based cardiometabolic care can be instructive for other at-risk populations.

La crisis humanitaria compleja (CHC) en Venezuela se caracteriza por la inseguridad alimentaria, la hiperinflación, la insuficiencia de servicios básicos y el colapso del sistema de salud. Se desconoce la evolución de la epidemiología de los factores de riesgo cardiometabólico en este contexto.

ObjetivoRecopilar evidencia de los últimos 20 años sobre la prevalencia de factores de riesgo cardiometabólico en adultos de Venezuela en el contexto del CHC.

MétodosRevisión bibliográfica exhaustiva de estudios poblacionales de adultos en Venezuela desde 2000 hasta 2020.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 7 estudios (EVESCAM Nacional 2014-2017, 3 regiones VEMSOLS 2006-2010, ciudad de Maracaibo 2007-2010, ciudad de Mérida 2015, ciudad de Mucuchíes 2009, ciudad de Barquisimeto CARMELA 2003-2005 y estado de Zulia 1999-2001) con tamaños de muestra variables desde 109 hasta 3.414 sujetos. A lo largo del tiempo, hubo una aparente disminución del consumo de tabaco del 21,8% (2003-2005) al 11,7% (2014-2017) y de la obesidad del 33,3% (2007-2010) al 24,6% (2014-2017). Por el contrario, hubo un aparente aumento de la diabetes del 6% (2003-2005) al 12,3% (2014-2017), la prediabetes del 14,6% (2006-2010) al 34,9% (2014-2017) y la hipertensión del 24,7% (2003-2005) al 34,1% (2014-2017). La dislipidemia más prevalente, el colesterol HDL bajo, se mantuvo entre el 65,3% (1999-2001) y el 63,2% (2014-2017). Desde 2006-2010 hasta 2014-207, el colesterol total alto (22,2% versus 19,8%, respectivamente) y el colesterol LDL alto (23,3% versus 20,5%, respectivamente) permanecieron similares, pero los triglicéridos altos disminuyeron (39,7% versus 22,7%, respectivamente). Utilizando la misma definición en todos los estudios, la prevalencia de síndrome metabólico aumentó del 35,6% (2006-2010) al 47,6% (2014-2017). La actividad física insuficiente se mantuvo estable entre 2007-2010 (34,3%) y 2014-2017 (35,2%).

ConclusiónLos cambios en la prevalencia de factores de riesgo cardiometabólicos en Venezuela son heterogéneos y pueden verse afectados por diversos determinantes sociales de la salud. Aunque el sistema de salud venezolano no se ha adaptado con éxito, la dinámica y las repercusiones del CHC en la atención cardiometabólica de la población pueden ser instructivas para otras poblaciones en riesgo.

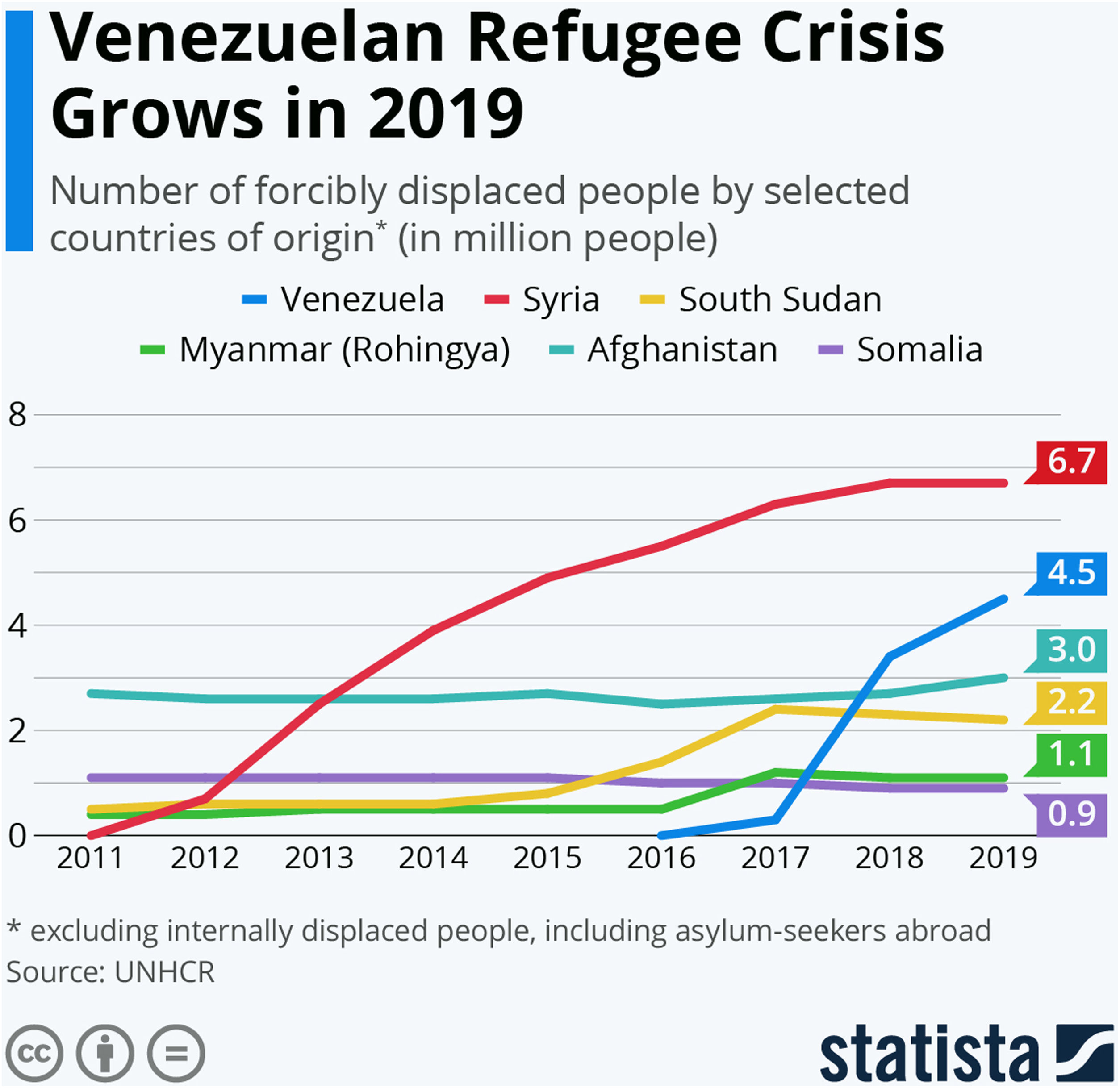

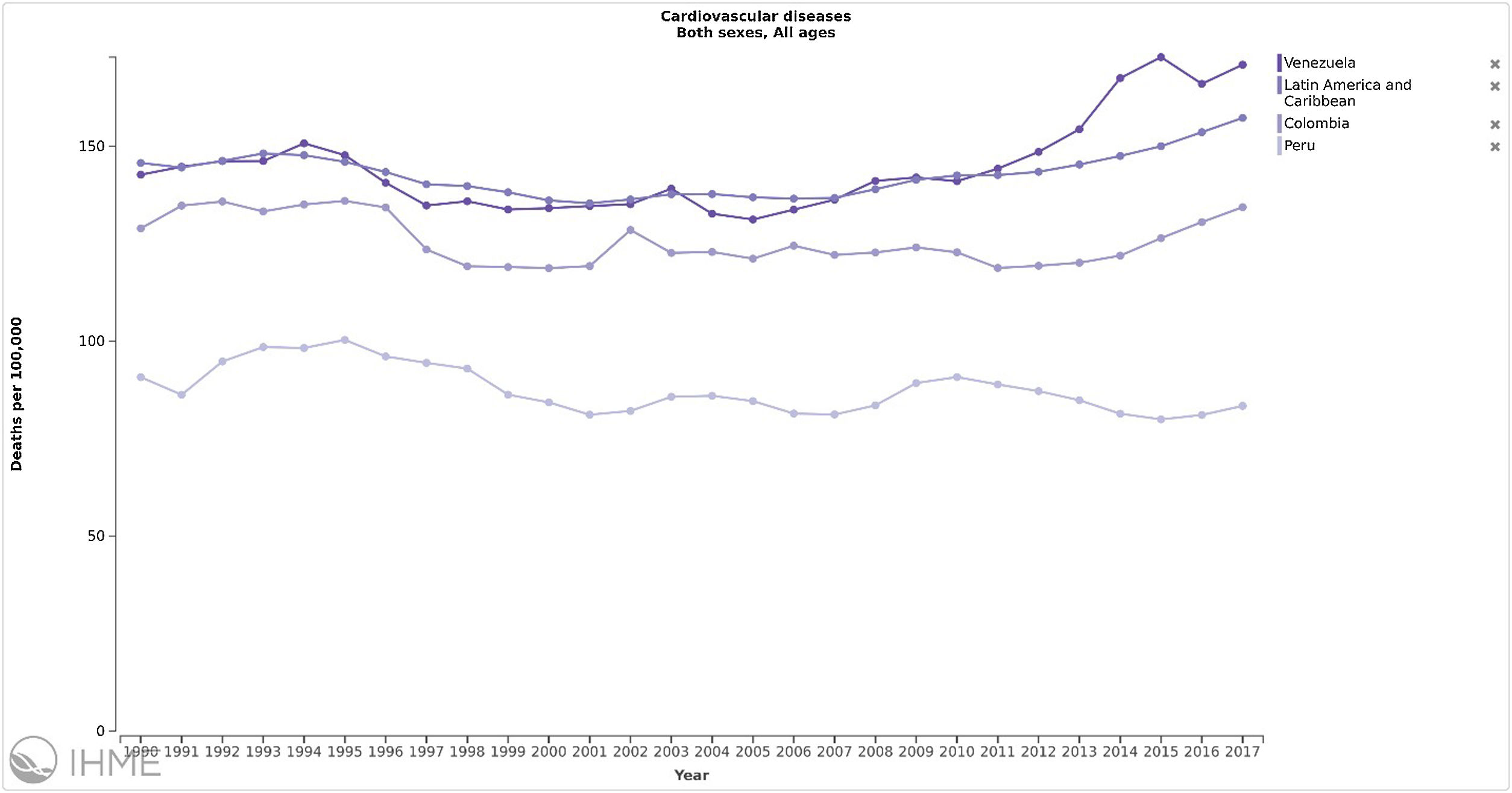

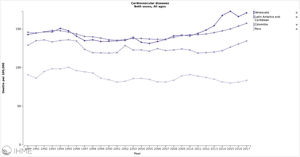

The influence of a totalitarian government in Venezuela for over two decades on the burden and epidemiology of cardiometabolic risk factors represents a huge concern.1 The characteristics of the complex humanitarian crisis (CHC) that created the collapse of the economy and the healthcare system2 challenge the management of chronic diseases, especially the development and progression of cardiometabolic risk factors. The shortage and high cost of food, and lack of transportation, gas, and electricity changed the routine behaviors of the population, including dietary intake. Additionally, and fueled by this crisis, in 2020, 5.4 million people across different socio-economic statuses (SES) have left the country.3–5 Because the world's biggest number of displaced persons from Syria is stabilizing (6.5 million internally displaced and 5.6 million left the country),6 Venezuelan migrants could become the biggest forced migration in the following years7 (Supplement Figure 1). How this adverse environment compromises cardiometabolic health remains unknown. Official data is scarce and untrustworthy.8 The Global Burden Diseases (GBD) reports that in Venezuela, there was an increase of 59.2% in the rate of deaths by cardiovascular disease (CVD), from 137 to 219 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants from 2000 to 2019, and the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for CVD increased by 44.2%.9 This can be compared with two neighboring countries during the same period: in Colombia, the mortality rate from CVD increased by 25.8% (about half of that seen in Venezuela) from 120 to 152 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants; and in Peru, the mortality rate from CVD increased by 7.0% (about 12% of that seen in Venezuela) from 80 to 88 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants9 (Supplement Figure 2).

In this narrative review, data from the last 20 years the prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in adults of Venezuela are compiled, analyzed, and interpreted in the context of the CHC and a healthcare system struggling to adapt. Conclusions drawn from this report are framed to be instructive, not only for Venezuelans, but also for other at-risk populations to better respond to CHCs in its various forms.

Methods and searchA comprehensive literature review from 2000 to 2020 was performed by two of the authors (RI and DDO) using the keywords “prevalence‿, “metabolic syndrome‿; “overweight‿; “obesity‿; “hypertension‿; “physical inactivity‿, “diabetes‿, “prediabetes‿, “dyslipidemia‿, “tobacco use‿, “smoking‿, and “Venezuela‿. The inclusion criteria were population-based studies of randomly selected samples of adults 18 years or older in the Venezuelan population, with data collected between January 1999 to October 2020, including sectors, parish, municipalities, cities, states, regions, or national representation. A total of 3307 references were identified in the databases used (PUBMED [1468], ScIELO [516], and LILACS [1323]). Then, the inclusion criteria to all the references were applied to determine their relevance, 13 articles were chosen. Having read the articles in full, the non-population-based studies, clinical data from healthcare centers and studies with unclear or poor methodology, were excluded. Finally, 7 articles were selected to be included in the review (Supplement Figure 3). Abstracts and full papers (either in English or Spanish) from the identified references were collected and screened. Literature not indexed, such as white papers, government publications, conference proceedings, and other gray literature was selected and included if considered appropriate.

Results and discussionDescription of studies includedSeven studies with data collected from 1999 to 2017, with samples sizes from 109 to 3414 subjects,10–20 and a total of 12,317 subjects were included. The most extensively studied regions were Zulia (n=5742; 3 studies),10,12,15,19 Western (n=2612; 3 studies),10–14 and the Andeans (n=1213; 4 studies).10,11,13,14,18. Only one study did not report the dates of data collection12; no pediatric studies were included (Table 1).

Prevalence of adult cardio-metabolic components in Venezuela (2001–2017).

| Authors/study | Year of publication (data collection, # in abstract) | Sample/location | n | Current smoking (%) | Obesity (%) | DM (%) | Pre-DM | HTN | Dyslipidemia (%) | Mets (%) | Physical inactivity (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High cholesterol | High LDL-c | Low HDL-c | High TG | |||||||||||

| Nieto-Martínez, R et al.EVESCAM10 | 2020 (2014–2017, study 1) | National sample | 3414 | 11.7 | 24.6 | 12.3 | 34.9 | 34.1 | 19.8 | 20.5 | 63.2 | 22.7 | 47.6 | 35.2 |

| Nieto-Martínez, R et al.VEMSOLS11,13,14,20 | 2018 (2006–2010, study 2) | 3 regions: Lara, Mérida, Distrito capital | 1334 | 29.3 | 8.3 | 14.6 | 31.3 | 22.2 | 23.3 | 58.6 | 39.7 | 35.6 | ||

| Bermudez, V et al.The Maracaibo city metabolic syndrome prevalence study15,16 | 2016 (2007–2010, study 3) | 1 city: Maracaibo (Zulia state) | 2230 | 14.9 | 33.3 | 8.8 | 57.4 | 28.0 | 34.3 | |||||

| Uzcátegui, E et al.12 | 2015 (N/R, study 4) | 1 city: Merida (Merida state) | 274 | 23.0 | 84.2 | 35.7 | 34.4 | |||||||

| Becerra Leal, A et al.17 | 2009 (2007, Study 5) | 1 city: Mucuchies (Merida state) | 109 | 33.0 | 76.0 | 56.0 | 43.0 | |||||||

| Schargrodsky, H et al.CARMELA18 | 2008 (2003–2005, Study 6) | 1 city: Barquisimeto (Lara state) | 1848 | 21.8 | 25.1 | 6.0 | 24.7 | 5.7 | 25.8 | |||||

| Florez, H et al.Zulia Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factor Study19 | 2005 (1999–2001, Study 7) | 1 state: Zulia state | 3108 | M: 7.8F: 7.4 | M: 19.6F: 14.9 | 65.3 | 32.3 | 31.2 | ||||||

Abbreviations: CARMELA: Cardiovascular Risk Factor Multiple Evaluation in Latin America Study; DM: diabetes mellitus; EVESCAM: Venezuelan Study of Cardiometabolic Health; LDL-c: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-c: high density lipoprotein cholesterol; MetS: metabolic syndrome; VEMSOLS: Venezuelan Metabolic Syndrome, Obesity and Lifestyle Study.

The Venezuelan Study of Cardio-Metabolic Health (EVESCAM, for its acronym in Spanish) was a population-based, cross-sectional, and randomized cluster sampling, of a nationally representative sample of 3414 adults 20 years or older evaluated from 2014 to 2017.10 The aim was to determine the prevalence of cardio-metabolic risk factors in adults; the EVESCAM was the first nationally representative study in Venezuela.

The Venezuelan Metabolic Syndrome, Obesity, and Lifestyle Study (VEMSOLS) was a cross-sectional sub-national population-based evaluation of 1334 subjects aged 20 years or older from three of the eight regions of Venezuela (Andes, Capital, and Central), assessed from 2006 to 2010.11,14 VEMSOLS was the first study presenting data from two or more regions of the country and the aim was to compare the prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors among regions.

The Maracaibo City Metabolic Syndrome Prevalence Study was a cross-sectional population-based evaluation of 2230 subjects aged 18 years or older assessed from 2007 to 2010. The aim of the study was to identify metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular risk factors in the adult population of Maracaibo, the second-largest city of Venezuela.15,19

In Merida, the largest city in the Andes of Venezuela, a representative sample of the city, including 274 subjects aged 18 years or older, was evaluated in a cross-sectional design to evaluate the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, its components variables, and insulin resistance biomarkers in the population.12 In Mucuchíes, a town in the Andes of Venezuela, cross-sectional population-based evaluation was conducted involving 109 subjects, aged 20–65 years, during 2007 to estimate the prevalence of metabolic syndrome.17

From 2003 to 2005, the Cardiovascular Risk Factor Multiple Evaluation in Latin America (CARMELA) study was performed. This cross-sectional, population-based evaluation of 11,550 subjects aged 25–64 years aimed to assess the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, carotid plaques, and carotid intima-media thickness in individuals living in major cities in 7 Latin American countries. In Venezuela, there were 1848 adults assessed from Barquisimeto city in the western region of the country.18

The Zulia Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factor Study was a cross-sectional population-based survey of 3108 adults aged 20 years or older from the Zulia State from 1999 to 2001.19 The aim of this study was to evaluate risk factors for atherosclerosis in the state's adult population and to develop population-based strategies aimed at changing unhealthy lifestyles and halting the increasing trend of CVD and type 2 diabetes in Venezuela.

The problem: prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in VenezuelaCurrent smokingFour studies reported the prevalence of current smoking.10,12,16,18 During 2003–2005, the prevalence of current smoking was similar in Barquisimeto city 21.8%18 and Merida city 23.0%,12 but higher than that observed in Maracaibo city – 14.9% in 2007–2010.16 The EVESCAM national representative data collected from 2014 to 2017 reported a prevalence of 11.7%.10 These results show a trend of reduction of current smoking in the country. In Venezuela, there is an intense campaign to limit tobacco use with increased taxation, banned advertising, and restricted smoking in public places.21 These results are consistent with the current trend in the reduction of tobacco use in the Americas, from 22.1% in 2007 to 17.4% in 2015.22 Data from 2015 presents a large difference in the prevalence among countries, ranging from 6.5% and 7.4% in Panama and Ecuador, respectively, to 35.9% and 38.7% in Cuba and Chile, respectively.22

ObesityFour studies reported the prevalence of obesity defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30kg/m2.10,11,13,20 Data collected between 2003 and 2005 (CARMELA) reported an obesity prevalence of 25.1% in Barquisimeto city, this prevalence was higher in two studies collected between 2006 and 2010, 33.3% in Maracaibo city and 29.3% in three regions of Venezuela, but most recent data from 2014 to 2017 presented a lower prevalence of obesity of 24.6%.10 Globally, there is a rise in the number of people with obesity, from 105 million in 1975 to 641 million in 201423 and it was expected to observe an increase in the EVESCAM study. However, there was an apparent reduction in Venezuela.

Since 2014, the Venezuelan scenario is, in many aspects, comparable with the economic crisis of Cuba at the beginning of the 90th decade after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the tightening of the US embargo. During this period, the Cuban gross domestic product fell – 6.7% and there was a severe shortage of food and failure in transportation, leading to an increase in physical activity. This was associated with a population weight loss of 5.5kg or about 1.5 points in the BMI.24 Before the Cuban crisis, the prevalence of obesity was 15%, and decreased to 7.5%, during the five years of the crisis,24 but then, increased progressively to reach 30.6% in women and 18.5% in men in 2014.25 The CHC in Venezuela share components with the Cuban crisis and could explain this apparent reduction in the prevalence of obesity.

Diabetes and prediabetesFive studies reported the prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes.10,11,15,18,19 From 1999 and 2001, the prevalence of diabetes was 7.8% in men and 7.4% in women of the Zulia State, from 2003 and 2005, 6.0% in Barquisimeto city, and from 2006 and 2010, 8.8% in Maracaibo city and 8.3% in the Andes, Central, and Capital regions. The prevalence of diabetes in the EVESCAM study from 2014 to 2017 was 12.3%, the highest reported in the country, showing an increasing trend in the prevalence of diabetes. Similarly, the prevalence of prediabetes also increased from 14.9% and 19.6% in men and women of Zulia, and 14.6% in the three regions of Venezuela from 2006 to 2010, to 34.9% from 2014 to 2017.

This apparent increase in the prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes could be attributed in part to changes in nutritional behaviors, but also the EVESCAM study was the only one using oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) which increased the detection of prediabetes and diabetes compared to the rest of studies that only used fasting blood glucose. Like obesity, the prevalence of diabetes is increasing worldwide. Despite the association of obesity and diabetes, in Venezuela, as reported in VEMSOLS study,26 higher BMI was not associated with higher prevalence of diabetes. The 2019 Atlas of the International Diabetes Federation reported that the number of people with diabetes increased from 151 million in 2000 to 463 million in 2014, with a global prevalence of 9.3%, and it is expected to increase by 51% in the next 25 years.27 In the South and Central American Region, the prevalence estimated of diabetes was 9.4% and impaired glucose tolerance of 10.1% in 2019,28 both lower than that observed in the EVESCAM study in 2014–2017(12.3%).10

HypertensionThree studies reported the prevalence of hypertension.10,14,18 From 2003 to 2005, the prevalence of hypertension was 24.7% in Barquisimeto city,18 from 2006 to 2010 31.3% in the Andes, Central, and Capital regions,14 and from 2014 to 2017 34.1% in the EVESCAM national study.10 These results show an increase in the prevalence of hypertension in the last two decades in multiple regions.29,30 In comparison, results from the PURE-LATAM study reported a prevalence of hypertension of 44.6% in six Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Uruguay) in adults 35–70 years old in 2017, ranging from 19.3% in Peru to 52.5% in Brazil,31 with an average rate of control of 20.4%.29,30

In Venezuela, comparing the VEMSOLS (2006–2010) and EVESCAM (2014–2017) studies, the proportion of subjects aware of their own hypertension increased from 67% to 72%, but the proportion of treated reduced from 56% to 51%, possibly related to the severe shortage of medications and high prices. Nevertheless, the proportion of subjects controlled (<140/90mmHg) increased from 9.9% to 33%, indicating an improvement in the management strategy of hypertension. It is critically important to know the role of lifestyle change in this setting.

DyslipidemiasEach of the seven studies reported the prevalence of dyslipidemias.10–19 The epidemiology of dyslipidemia is difficult to compare across the studies because there are several types of dyslipidemias, without agreements on definitions. Among the dyslipidemias studied, low HDL-cholesterol was the most prevalent, ranging from 57.4% in Maracaibo city to 84.2% in Merida city, without apparent changes overtime (65.3%, 1999–2001 vs. 63.2%, 2014–2017). High triglycerides was the second most prevalent dyslipidemia, ranging from 22.7% in the national sample to 56.0% in the rural population of Mucuchies in Merida State and lower in 2006–2010 (39.7%) and 2014–2017 (22.7%). The prevalence of high cholesterol showed a large variation, from 5.7% in Barquisimeto city in 2003–2005 (defined as a total cholesterol ≥240mg/dL) to 33.0% in the rural population of Mucuchies in Merida State (defined as a total cholesterol ≥200mg/dL). For VEMSOLS (2006–2010) and EVESCAM (2014–2017), the prevalence of high cholesterol (defined as a total cholesterol ≥200mg/dL) and high LDL-c (defined as LDL-c ≥130mg/dL) was similar, 22.2% vs. 19.8% and 23.3% vs. 20.5%, respectively.

Globally, from 1980 to 2018, there are changes in the prevalence of high cholesterol varied with different populations,31 the total cholesterol values decreased in high-income western regions and central and eastern Europe, and increased in east and southeast Asia, without major changes in other regions. This repositions the epicenter of dyslipidemia from high-income countries in northwestern Europe, North America, and Australasia to middle-income countries in east and southeast Asia, as well as some countries in Oceania and central Latin America.31 A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies assessing dyslipidemias prevalence in Latin America and the Caribbean, with studies published between 1964 and 2016, showed no significant changes in prevalence rates.32 The pooled prevalence in the region since 2005 were high total cholesterol 20.9% (cholesterol ≥240mg/dL) and 34.0% (cholesterol ≥200mg/dL); high LDL-c 19.7% (LDL-c ≥160mg/dL) and 40.4% (LDL-c ≥130mg/dL); low HDL-c 48.2% (HDL-c ≤40mg/dL in men and ≤50mg/dL in women); and high triglycerides 20.4% (triglycerides ≥200mg/dL) or 43.1% (triglycerides ≥150mg/dL).32 The results of this meta-analysis highlight that in Latin America, low HDL-c and high triglycerides are the most common lipid alterations.32 Consequently, a group of experts of the Latin American Academy for the study of Lipids (ALALIP) presented in 2017 a position statement that reinforces the recognition that atherogenic dyslipidemia, the combination of high triglycerides and low HDL-c, is highly prevalent in Latin America, probably as a reflection of genetic predisposition, epigenetic modifications, and unhealthy diet, and therefore needs to be more thoroughly evaluated in a large regional study.33

Metabolic syndromeSix studies reported the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, which also has different definitions.10,12,17–20 The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Venezuela shows large variation without any apparent trend, ranging from 25.8% in Barquisimeto city in 2003–2005 to 47.6% in the national sample in 2014–2017. But, using the same definition, metabolic syndrome prevalence increased from 35.6% (2006–2010, VEMSOLS) to 47.6% (2014–2017, EVESCAM). A systematic review including studies reporting the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Latin America presented a weighted mean of 24.9%, with a wide range of variation, from 18.8% in Peru to 43.3% in Puerto Rico.34

Since the first definition of metabolic syndrome, there has been considerable disagreement about clinical relevance and utility identifying people at risk.35 In 2020, a Cardiometabolic-Based Chronic Disease (CMBCD) model that provides a preventive care plan designed to implement early and sustainable evidence-based therapeutic targeting to promote cardiometabolic health was proposed that provides pragmatic context for the metabolic syndrome.36,37 The CMBCD model integrates two novel diagnostic frameworks for adiposity and dysglycemia, Adiposity-Based Chronic Disease (ABCD)38 and Dysglycemia-Based Chronic Disease (DBCD).39 The ABCD model is a complication-centric rather than a BMI-centric approach that incorporates adipose tissue distribution and function in addition to just amount, and the DBCD model is a complication-centric, rather than glucocentric approach that configures insulin resistance, prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, and vascular complications along a spectrum. A CMBCD preventive care plan emphasizes the proactive search for cardiovascular complications and incorporates primordial prevention of cardiovascular risk development in the general population (stage 1), primary prevention of disease in patients at risk and with pre-disease (stage 2), secondary prevention of disease progression in patients with early disease (stage 3), and tertiary prevention of worsening symptom burden in patients with late disease (stage 4).37

Physical inactivityTwo studies reported the prevalence of insufficient physical activity using the International Questionnaire of Physical Activity (IPAQ), defined as less than 150min of moderate-intensity, 75min of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week, or a combination of the two.10,15 Both studies reported a similar prevalence, 34.3% in Maracaibo city (2007–2010) and 35.2% in the national sample (2014–2017), inferring that between those time periods the prevalence of insufficient physical activity remained steady. In a global study including 1.9 million subjects, the prevalence of insufficient physical activity was 27.5% in 2016, stable since 2001, but with regional differences.40 In Latin America and the Caribbean, insufficient physical activity increased from 33.4% in 2001 to 39.1% in 2016,40 it is likely that this prevalence is currently lower in Venezuela based on the severe shortage of gasoline and transportation. However, the high level of insecurity and violence reduce the exposure of people to activities outside their homes, mitigating any presumed benefit.

Nutritional intakeIn EVESCAM (2014–2017), dietary intake was assessed using a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire and a dietary diversity score. The most frequently consumed foods were coffee, arepas (a salted corn flour cake), and cheese. Western foods were consumed infrequently with over 75% of participants consuming French fries, burgers, and fast foods only monthly or less frequently. Dietary diversity is low with the CHC in Venezuela. Although dietary diversity was similar in both genders, females had healthier diets than males, with lower consumption of white bread, red meat, and soft drinks. Men, younger individuals, and those with higher SES were more likely to consume red meat and soft drinks once or more weekly. Women and those with higher SES were more likely to consume vegetables and cheese once or more daily. Participants with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension had a lower daily intake of red meat and arepas compared to participants without these risk factors. Nutrition transition, replacement of healthy foods by ultra-processed foods, which is observed elsewhere in Latin America, seems not to be the case in Venezuela.41

The context: complex humanitarian crisis and forced migrationVenezuela is facing a CHC driven by a severe economic and political crisis with food insecurity, hyperinflation, shortages of medicines and gasoline, insufficient basic services (water, domestic gas, and especially electricity), social conflicts, and a collapse of the healthcare system.1,2 This situation has incited 5.4 million Venezuelans to leave the country. Although since March 2020, the COVID 19 pandemic generated multiple lockdowns that halted the migration, the new migrant wave will encounter more adverse conditions generated by the COVID 19 contagion fear such as shelters closed, fewer pickups to walkers, locals less likely to help with food donations, as well as fewer employment opportunities, and more congested healthcare services in recipient countries.

This context of crisis, with the respective nutritional situation, could determine some changes in the classic association between cardio metabolic risk factors. Even with an apparent reduction in obesity prevalence, there is an apparent increase in hypertension prevalence, which could be explained by the complex humanitarian crisis that expose the people to chronic stressors. This contrast with the previously described trend in cardiometabolic risk factors in the Americas from 1980 to 2014,25 where Venezuela reported an increase in diabetes and obesity, and a decrease in hypertension.

Venezuelan health care systemPatients with CMBCD need a complex health system infrastructure to achieve remission, control and avoid complications. Challenges for prevention and treatment of these conditions in humanitarian settings include lack of anticipation within the emergency response, limited access to healthcare, reduced continuity of care, impossibility for a regular diet and physical activity, unpredictable medication access, interruption of self-management in the case of diabetes, and the complex coordination needed to provide adequate health care.

The collapse of hospital services has been reported annually since 2017 by the National Hospital Survey.42 In 2019, 50% of the operating rooms, radiology, laboratory, and ultrasound services, and 70% of the tomography and magnetic resonance services were not operative. A number of 1557 deaths were reported that year consequence of the lack of resources. A 78% of hospitals presented an absolute or intermittent failure in the supply of water and 63% absolute or intermittent failure electricity. This was associated with 79 deaths of hospitalized patients attributed to electricity failures. Between the 2018 to 2019, there was a reduction in 10% of physicians and 24% of nurses caused by emigration.43

LimitationsThe main limitation of this review is the cross-sectional design of the studies included impeding to determine causal relationships. The studies included report cardio-metabolic risk factors in different locations and populations of the country, with only one study having a national sample. The difference between each population and how this influences cardio-metabolic health is not determined; socioeconomic and cultural differences could explain the variability. The EVESCAM follow-up study, 2018–2020, the first cohort study with a national representative sample will provide data about changes in cardio-metabolic risk factors in the CHC context. The strengths of this report include the review of all cardiometabolic population-based studies done in Venezuela, including national representativeness of EVESCAM study and a unique setting influenced by extraordinary stress.

ConclusionThe epidemiology of cardiometabolic risk factors has worsened in Venezuela in the last two decades. Although an apparent decrease was observed for smoking and obesity, the prevalence of diabetes, prediabetes, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome increased, with no apparent changes in dyslipidemias and physical inactivity. These complex and divergent changes are influenced by a CHC generated by the collapse of the economy and the consequent exhaustion of an already fragmented and inefficient healthcare system. This situation imposes extraordinary challenges for the prevention and management of cardiometabolic chronic diseases and risk factors, which lead to further morbidities and suffering, further impelling this vicious cycle. Participation of all stakeholders is urgently needed to design and implement an innovative and adaptive healthcare system design that ameliorates the burden of chronic cardiometabolic disease in Venezuela.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.