Prediabetes is a major public health problem. The aims of the SIMETAP-PRED study were to determine the prevalence rates of prediabetes according to two diagnostic criteria, and to compare the association of cardiometabolic and renal risk factors between populations with and without prediabetes.

MethodsCross-sectional observational study conducted in Primary Care. Based random sample: 6588 study subjects (response rate: 66%). Two diagnostic criteria for prediabetes were used: 1. Prediabetes according to the Spanish Diabetes Society (PRED-SDS): Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) 110–125 mg/dL or HbA1c 6.0%–6.4%; 2. Prediabetes according to the American Diabetes Association (PRED-ADA): FPG 100–125 mg/dL or HbA1c 5.7%–6.4%. The crude and sex- and age-adjusted prevalence rates, and cardiometabolic and renal variables associated with prediabetes were assessed.

ResultsThe crude prevalence rates of PRED-SDS and PRED-ADA were 7.9% (95%CI 7.3–8.6%), and 22.0% (95%CI 21.0%–23.0%) respectively, their age-adjusted prevalence rates were 6.6% and 19.1 respectively. The high or very high cardiovascular risk (CVR) of the PRED-SDS or PRED-ADA populations were 68.6% (95%CI 64.5%–72.6%) and 61.7% (95%CI 59.1%–64.1%) respectively. Hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, overweight, obesity, and increased waist-to-height ratio were independently associated with PRED-SDS. In addition to these factors, low glomerular filtration rate and hypercholesterolemia were also independently associated with PRED-ADA.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of PRED-ADA triples that of PRED-SDS. Two thirds of the population with prediabetes had a high CVR. Several cardiometabolic and renal risk factors were associated with prediabetes. Compared to the SDS criteria, the ADA criteria make the diagnosis of prediabetes easier.

La prediabetes constituye un importante problema de salud pública. Los objetivos del estudio fueron determinar la prevalencia de prediabetes según dos criterios diagnósticos, y comparar la asociación de factores de riesgo cardiometabólicos y renales entre las poblaciones con y sin prediabetes.

MétodosEstudio observacional transversal realizado en el ámbito de Atención Primaria. Muestra aleatoria de base poblacional: 6.588 sujetos de estudio (tasa de respuesta: 66%). Se utilizaron dos criterios diagnósticos: 1. Prediabetes según la Sociedad Española de Diabetes (PRED-SED): Glucosa plasmática en ayunas (GPA) 110–125 mg/dL o HbA1c 6,0%–6,4%; 2. Prediabetes según la Asociación Americana de Diabetes (PRED-ADA): GPA 100–125 mg/dL o HbA1c 5,7%–6,4%. Se evaluaron las prevalencias crudas y ajustadas por edad y sexo, y las variables cardiometabólicas y renales asociadas con prediabetes.

ResultadosLas prevalencias crudas de PRED-SED y PRED-ADA fueron 7,9% (IC95% 7,3%–8,6%), y 22,0% (IC95% 21,0%–23,0%) respectivamente, y sus prevalencias ajustadas fueron 6,6% y 19,1% respectivamente. El riesgo cardiovascular (RCV) alto o muy alto de las poblaciones PRED-SED y PRED-ADA fueron 68,6% (IC95% 64,5%–72,6%) y 61,7% (IC95% 59,1%–64,1%) respectivamente. La hipertensión, hipertrigliceridemia, sobrepeso, obesidad y el índice cintura-talla aumentado se asociaban independientemente con PRED-SED. Además de estos factores, el filtrado glomerular bajo y la hipercolesterolemia también se asociaban independientemente con PRED-ADA.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de PRED-ADA triplica a la PRED-SED. Dos tercios de la población con prediabetes tenía un RCV elevado. Varios factores de riesgo cardiometabólicos y renales se asociaban con la prediabetes. En comparación con los criterios de la SED, los criterios de la ADA facilitan más el diagnóstico de la prediabetes.

Prediabetes is an intermediate metabolic state between normoglycaemia and diabetes (DM), pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction occurs as it develops in response to stressors such as lipotoxicity and/or glucotoxicity, affecting hepatic and peripheral glucose metabolism due to decreased insulin sensitivity (insulin resistance) and an initial increase in insulin secretion (hyperinsulinaemia).1–3

The presence of cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs) that are highly prevalent during the pre-diabetic period, such as obesity, high blood pressure (HBP), and atherogenic dyslipidaemia,4–6 may largely account for its association with the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACVD) and chronic kidney disease,6,7 which promotes an atherogenic pattern leading to structural and functional damage of the vascular endothelium.7,8 This implies a potential increase in cardiovascular risk4,8–10 (CVR) starting from glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels of 5.7%, or fasting plasma glucose (FPG) concentrations as low as 100 mg/dL. However, individuals with prediabetes without ACVD are not necessarily at elevated CVR,10,11 and therefore require CVR assessment like the general population.11

The diagnostic criteria values used by different societies to define prediabetes vary according to the choice of HbA1c range or the FPG concentrations that define impaired fasting glucose (IFG), and this has implications for the detection and burden of prediabetes12 and for the risk of developing DM.1,2

Prediabetes is a major public health problem, not only because of its likely progression to DM,1,2 but also because of its increased CVR burden and the high prevalence of associated comorbidities.6,8–10 Most individuals with prediabetes are unaware of its associated increased CVR and that lifestyle changes can reduce or delay the onset of DM.13

The prevalence of prediabetes increases progressively with age due to changes in glucose metabolism, body composition, and unhealthy lifestyle.13 The annual worldwide incidence of DM and prediabetes continues to increase. If 463 million people had DM in 2019, this figure could rise to 578 million by 2030 and to 700 million by 2045. In parallel, prediabetes considered as IFG, which affected 374 million people in 2019, could reach 454 million by 2030 and 548 million by 2045.14

Knowledge of the epidemiological situation of prediabetes and its relationship with its potential associated cardiometabolic and renal factors is a key challenge to avoid the progression of the disease and the economic burden entailed for the healthcare system,6 as well as to implement easily applied prevention measures, such as smoking cessation and intervention on diet and exercise.13

The objectives of the SIMETAP-PRED study were to determine the prevalence rates of prediabetes in the adult population according to two diagnostic criteria, and to compare the association of CVRFs, cardiometabolic and renal, in populations with and without prediabetes.

Material and methodsSIMETAP-PRED is a cross-sectional observational study, authorised by the Health Service of the Community of Madrid (SERMAS), in which 121 family doctors participated, competitively selected to reach the required sample size, from 64 primary care centres (25% of the SERMAS Health Centres). Information on the material and methods (design, sampling, recruitment, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data collection, statistical analysis, and criteria defining the variables and categories of CVR) of the SIMETAP study have been detailed previously in this journal.15 A total of 6588 study subjects recruited by simple randomised sampling from the adult population assigned to the SERMAS primary care physicians participating in the study were included, with a response rate of 65.8%. By protocol, patients who were terminally ill, institutionalised, cognitively impaired, pregnant or subjects without information on biochemical variables were excluded, and informed consent was obtained from all the study subjects.

The biochemical criteria to diagnose DM were those of the American Diabetes Association (ADA)16: fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 126 mg/dL (≥7.0 mmol/l) or HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (≥48 mmol/mol) confirmed at least twice, or plasma glucose test ≥ 200 mg/dL (≥11.1 mmol/l), taken either randomly at any time of the day regardless of the interval since the last meal, or with the oral glucose tolerance test (2 h after administration of 75 g of anhydrous glucose dissolved in water). The patients were also considered to have DM if the diagnosis had been verified in their medical records. In study subjects without DM, two diagnostic criteria for prediabetes were used: 1) prediabetes diagnosed according to the Spanish Diabetes Society17 (PRED-SED): FPG between 110 and 125 mg/dL (6.1–6.9 mmol/l) or HbA1c between 6.0% and 6.4% (42–47 mmol/mol). 2) Prediabetes diagnosed according to the ADA16 (PRED-ADA): FPG between 100 and 125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/l) or HbA1c between 5.7% and 6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol).

The following cardiometabolic and renal variables were also considered: body mass index (BMI): weight/height2 (kg/m2). Overweight: BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2. Obese: BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Adiposity or body fat index CUN-BAE (Clínica Universitaria de Navarra-Body Adiposity Estimator)18: −44.988 + (.503 × age) + (10.689 × sex) + (3.172 × BMI)−(.026 × BMI2) + (.181 × BMI × sex)−(.02 × BMI × age)−(.005 × BMI2 × sex) + (.00021 × BMI2 × age); male sex = 0; female sex = 1. CUN-BAE-obesity: >25% (men); >35% (women). Central obesity: increased abdominal circumference (≥102 cm [men] or ≥88 cm [women]). Waist-to-height ratio (WHtR): abdominal circumference/height. Increased WtHR: WHtR ≥ .6. SBP: systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or on antihypertensive treatment. HbA1c standardised according to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). Hypercholesterolaemia: total cholesterol (TC) ≥ 200 mg/dL. Hypertriglyceridaemia (HTG): triglycerides (TG) ≥ 150 mg/dL. High density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). Low HDL-C: HDL < 40 mg/dL (men); <50 mg/dL (women). Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). Very low density lipoprotein remnant cholesterol (VLDL-C). Atherogenic index of plasma (AIP)): log (TG/HDL-C). Triglyceride-glucose index (TyG): Ln [TG × FPG/2]. Atherogenic dyslipidaemia: HTG and low HDL-C. Metabolic syndrome (MS): harmonised consensus IDF/NHLBI/AHA/WHF/IAS/IASO.19 Coronary heart disease: ischaemic heart disease, previous acute myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndromes, coronary revascularisation, arterial revascularisation procedures. Stroke: cerebrovascular accident, cerebral ischaemia or intracranial haemorrhages and transient ischaemic attack. Peripheral arterial disease: intermittent claudication or an ankle-brachial index ≤ .9. CHD: coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral arterial disease. Albuminuria: albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) ≥ 30 mg/g. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) according to Chronic Kidney Disease EPIdemiology collaboration (CKD-EPI). Low eGFR: eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Chronic kidney disease: low eGFR and/or albuminuria. CVR according to SCORE.20,21

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis determined the mean and standard deviation (±SD) of continuous variables. Qualitative variables were analysed as percentages in each category, presented with lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence interval (CI). Prevalence rates were determined as crude rates and age- and sex-adjusted rates. Rates were adjusted for age and sex by ten-year age groups standardised to those of the Spanish population using the direct method. Data for the Spanish population in January 2015 were obtained from the National Institute of Statistics database.22

Prevalence rates were standardised by age and sex according to the Spanish population to facilitate comparison with other populations. Comparisons of continuous variables were performed using the Student's t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical variables were analysed using the χ2 test. Odds ratios (OR) were determined with 95% CI. To assess the individual effect of CVRF and comorbidities on the dependent PRED-ADA and PRED-SED variables, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed using backward stepwise regression, initially introducing into the model all variables that showed an association in the univariate analysis up to a value of P < .10, and subsequently eliminating at each step the variable that contributed least to the model fit. In the multivariate analyses, the following variables were excluded: CUN-BAE-obesity,18 atherogenic dyslipidaemia, ACVD, and MS,19 as the components of these variables were already included in the analysis, and erectile dysfunction as it only affects men. All tests were considered statistically significant if the two-tailed P-value was less than .05. We conducted a literature search in PubMed, Medline, Embase, Google Scholar, and Web of Science to compare the prevalence rates of the present study with similar studies from the last 15 years.

ResultsThe study population was 6588 adults aged 18.0–102.8 years with a mean (±SD) age of 55.1 (±17.5) years. The percentage difference between males (44.1% [CI 42.9%–45.3%]) and females (55.9% [CI 54.7%–57.1%]) was significant (P < .001). The difference in mean [±SD] age between the male (55.3 [±16.9] years) and female (55.0 [±18.0] years) populations was not significant (P = .634).

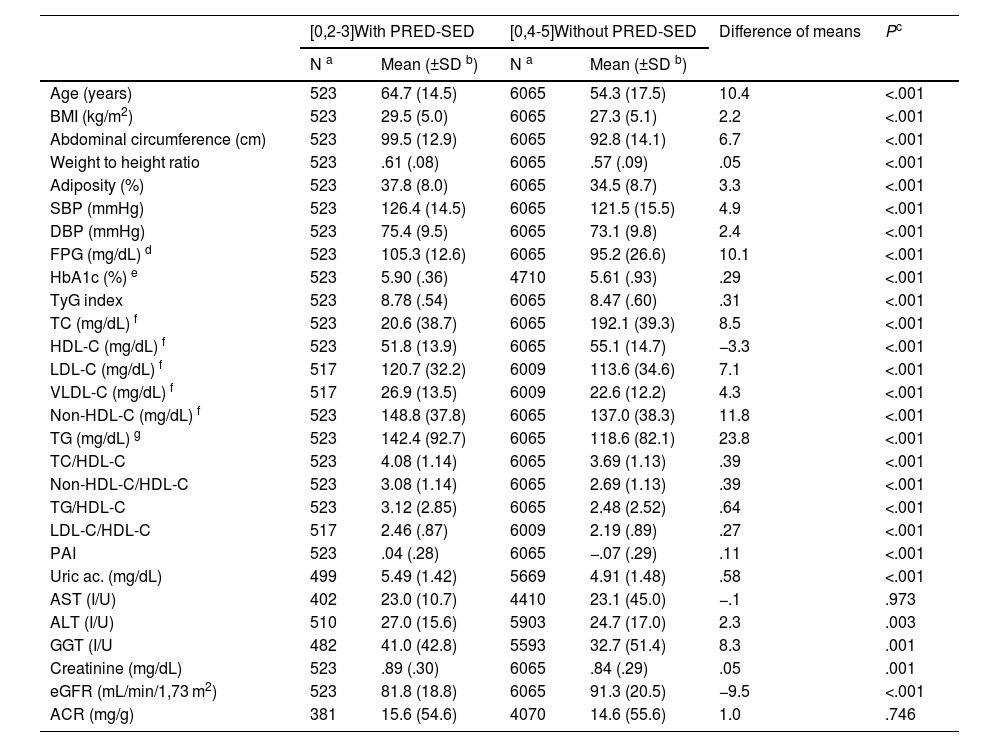

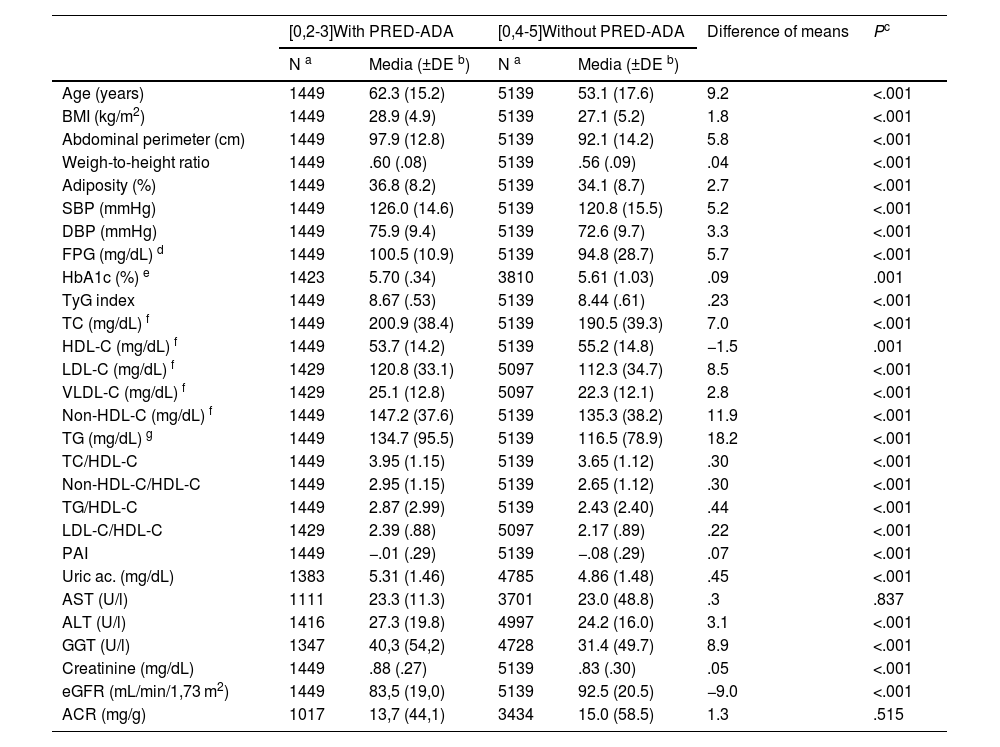

The difference in the percentage of the male population between the populations with PRED-SED (48.4% [CI 44.1%–52.7%]) and without PRED-SED (43.7% [CI 42.5%–45.0%]) was significant (P = .039). The difference in the percentage of the male population between the populations with PRED-ADA (48.9% [46.4%−51.5%]) and without PRED-ADA (42.7% [41.4%–44.1%]) was significant (P < .001). The difference in mean age between the PRED-SED and PRED-ADA populations (2.4 [95% CI: .9–3.9] years) was significant (P = .002). The differences in clinical characteristics between populations with and without prediabetes are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Clinical characteristics of the populations with and without PRED-SED.

| [0,2-3]With PRED-SED | [0,4-5]Without PRED-SED | Difference of means | Pc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N a | Mean (±SD b) | N a | Mean (±SD b) | |||

| Age (years) | 523 | 64.7 (14.5) | 6065 | 54.3 (17.5) | 10.4 | <.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 523 | 29.5 (5.0) | 6065 | 27.3 (5.1) | 2.2 | <.001 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 523 | 99.5 (12.9) | 6065 | 92.8 (14.1) | 6.7 | <.001 |

| Weight to height ratio | 523 | .61 (.08) | 6065 | .57 (.09) | .05 | <.001 |

| Adiposity (%) | 523 | 37.8 (8.0) | 6065 | 34.5 (8.7) | 3.3 | <.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 523 | 126.4 (14.5) | 6065 | 121.5 (15.5) | 4.9 | <.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 523 | 75.4 (9.5) | 6065 | 73.1 (9.8) | 2.4 | <.001 |

| FPG (mg/dL) d | 523 | 105.3 (12.6) | 6065 | 95.2 (26.6) | 10.1 | <.001 |

| HbA1c (%) e | 523 | 5.90 (.36) | 4710 | 5.61 (.93) | .29 | <.001 |

| TyG index | 523 | 8.78 (.54) | 6065 | 8.47 (.60) | .31 | <.001 |

| TC (mg/dL) f | 523 | 20.6 (38.7) | 6065 | 192.1 (39.3) | 8.5 | <.001 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) f | 523 | 51.8 (13.9) | 6065 | 55.1 (14.7) | −3.3 | <.001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) f | 517 | 120.7 (32.2) | 6009 | 113.6 (34.6) | 7.1 | <.001 |

| VLDL-C (mg/dL) f | 517 | 26.9 (13.5) | 6009 | 22.6 (12.2) | 4.3 | <.001 |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) f | 523 | 148.8 (37.8) | 6065 | 137.0 (38.3) | 11.8 | <.001 |

| TG (mg/dL) g | 523 | 142.4 (92.7) | 6065 | 118.6 (82.1) | 23.8 | <.001 |

| TC/HDL-C | 523 | 4.08 (1.14) | 6065 | 3.69 (1.13) | .39 | <.001 |

| Non-HDL-C/HDL-C | 523 | 3.08 (1.14) | 6065 | 2.69 (1.13) | .39 | <.001 |

| TG/HDL-C | 523 | 3.12 (2.85) | 6065 | 2.48 (2.52) | .64 | <.001 |

| LDL-C/HDL-C | 517 | 2.46 (.87) | 6009 | 2.19 (.89) | .27 | <.001 |

| PAI | 523 | .04 (.28) | 6065 | −.07 (.29) | .11 | <.001 |

| Uric ac. (mg/dL) | 499 | 5.49 (1.42) | 5669 | 4.91 (1.48) | .58 | <.001 |

| AST (I/U) | 402 | 23.0 (10.7) | 4410 | 23.1 (45.0) | −.1 | .973 |

| ALT (I/U) | 510 | 27.0 (15.6) | 5903 | 24.7 (17.0) | 2.3 | .003 |

| GGT (I/U | 482 | 41.0 (42.8) | 5593 | 32.7 (51.4) | 8.3 | .001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 523 | .89 (.30) | 6065 | .84 (.29) | .05 | .001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1,73 m2) | 523 | 81.8 (18.8) | 6065 | 91.3 (20.5) | −9.5 | <.001 |

| ACR (mg/g) | 381 | 15.6 (54.6) | 4070 | 14.6 (55.6) | 1.0 | .746 |

ACR: albumin-to-creatinine ratio; Adiposity: adiposity or body fat index (Clínica Universitaria de Navarra–Body Adiposity Estimator); ALT: alanine-aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; BMI: body mass index; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate according to CKD-EPI; GGT: gamma glutamyl transferase; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Non-HDL-C: non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PAI: plasma atherogenic index (log [TG/cHDL]); PRED-SED: prediabetes according to the Spanish Diabetes Society (fasting plasma glucose [FPG] 110–125 mg/dL or glycated haemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] 6.0%–6.4%); SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; TyG index: Triglyceride glucose index (Ln [TGxFPG/2]); VLDL-C: very low density lipoprotein remnant cholesterol.

Clinical characteristics of populations with and without PRED-ADA.

| [0,2-3]With PRED-ADA | [0,4-5]Without PRED-ADA | Difference of means | Pc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N a | Media (±DE b) | N a | Media (±DE b) | |||

| Age (years) | 1449 | 62.3 (15.2) | 5139 | 53.1 (17.6) | 9.2 | <.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1449 | 28.9 (4.9) | 5139 | 27.1 (5.2) | 1.8 | <.001 |

| Abdominal perimeter (cm) | 1449 | 97.9 (12.8) | 5139 | 92.1 (14.2) | 5.8 | <.001 |

| Weigh-to-height ratio | 1449 | .60 (.08) | 5139 | .56 (.09) | .04 | <.001 |

| Adiposity (%) | 1449 | 36.8 (8.2) | 5139 | 34.1 (8.7) | 2.7 | <.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 1449 | 126.0 (14.6) | 5139 | 120.8 (15.5) | 5.2 | <.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 1449 | 75.9 (9.4) | 5139 | 72.6 (9.7) | 3.3 | <.001 |

| FPG (mg/dL) d | 1449 | 100.5 (10.9) | 5139 | 94.8 (28.7) | 5.7 | <.001 |

| HbA1c (%) e | 1423 | 5.70 (.34) | 3810 | 5.61 (1.03) | .09 | .001 |

| TyG index | 1449 | 8.67 (.53) | 5139 | 8.44 (.61) | .23 | <.001 |

| TC (mg/dL) f | 1449 | 200.9 (38.4) | 5139 | 190.5 (39.3) | 7.0 | <.001 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) f | 1449 | 53.7 (14.2) | 5139 | 55.2 (14.8) | −1.5 | .001 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) f | 1429 | 120.8 (33.1) | 5097 | 112.3 (34.7) | 8.5 | <.001 |

| VLDL-C (mg/dL) f | 1429 | 25.1 (12.8) | 5097 | 22.3 (12.1) | 2.8 | <.001 |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) f | 1449 | 147.2 (37.6) | 5139 | 135.3 (38.2) | 11.9 | <.001 |

| TG (mg/dL) g | 1449 | 134.7 (95.5) | 5139 | 116.5 (78.9) | 18.2 | <.001 |

| TC/HDL-C | 1449 | 3.95 (1.15) | 5139 | 3.65 (1.12) | .30 | <.001 |

| Non-HDL-C/HDL-C | 1449 | 2.95 (1.15) | 5139 | 2.65 (1.12) | .30 | <.001 |

| TG/HDL-C | 1449 | 2.87 (2.99) | 5139 | 2.43 (2.40) | .44 | <.001 |

| LDL-C/HDL-C | 1429 | 2.39 (.88) | 5097 | 2.17 (.89) | .22 | <.001 |

| PAI | 1449 | −.01 (.29) | 5139 | −.08 (.29) | .07 | <.001 |

| Uric ac. (mg/dL) | 1383 | 5.31 (1.46) | 4785 | 4.86 (1.48) | .45 | <.001 |

| AST (U/l) | 1111 | 23.3 (11.3) | 3701 | 23.0 (48.8) | .3 | .837 |

| ALT (U/l) | 1416 | 27.3 (19.8) | 4997 | 24.2 (16.0) | 3.1 | <.001 |

| GGT (U/l) | 1347 | 40,3 (54,2) | 4728 | 31.4 (49.7) | 8.9 | <.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1449 | .88 (.27) | 5139 | .83 (.30) | .05 | <.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1,73 m2) | 1449 | 83,5 (19,0) | 5139 | 92.5 (20.5) | −9.0 | <.001 |

| ACR (mg/g) | 1017 | 13,7 (44,1) | 3434 | 15.0 (58.5) | 1.3 | .515 |

ACR: Albumin-to-creatinine ratio; Adiposity: Adiposity or body fat index (Clínica Universitaria de Navarra–Body Adiposity Estimator); ALT: Alanine-aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; BMI: Body Mass Index; DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate according to CKD-EPI; GGT: Gamma Glutamyl Transferase; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Non-HDL-C: non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PAI: Plasma Atherogenic Index (log [TG/cHDL]); PRED-ADA: Prediabetes according to the American Diabetes Association (fasting plasma glucose [FPG] 100–125 mg/dL or glycated haemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] 5.7%–6.4%); SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure; TC: Total Cholesterol; TG: Triglycerides; TyG index: Triglyceride glucose index (Ln [TGxFPG/2]); VLDL-C: Very low density lipoprotein remnant cholesterol.

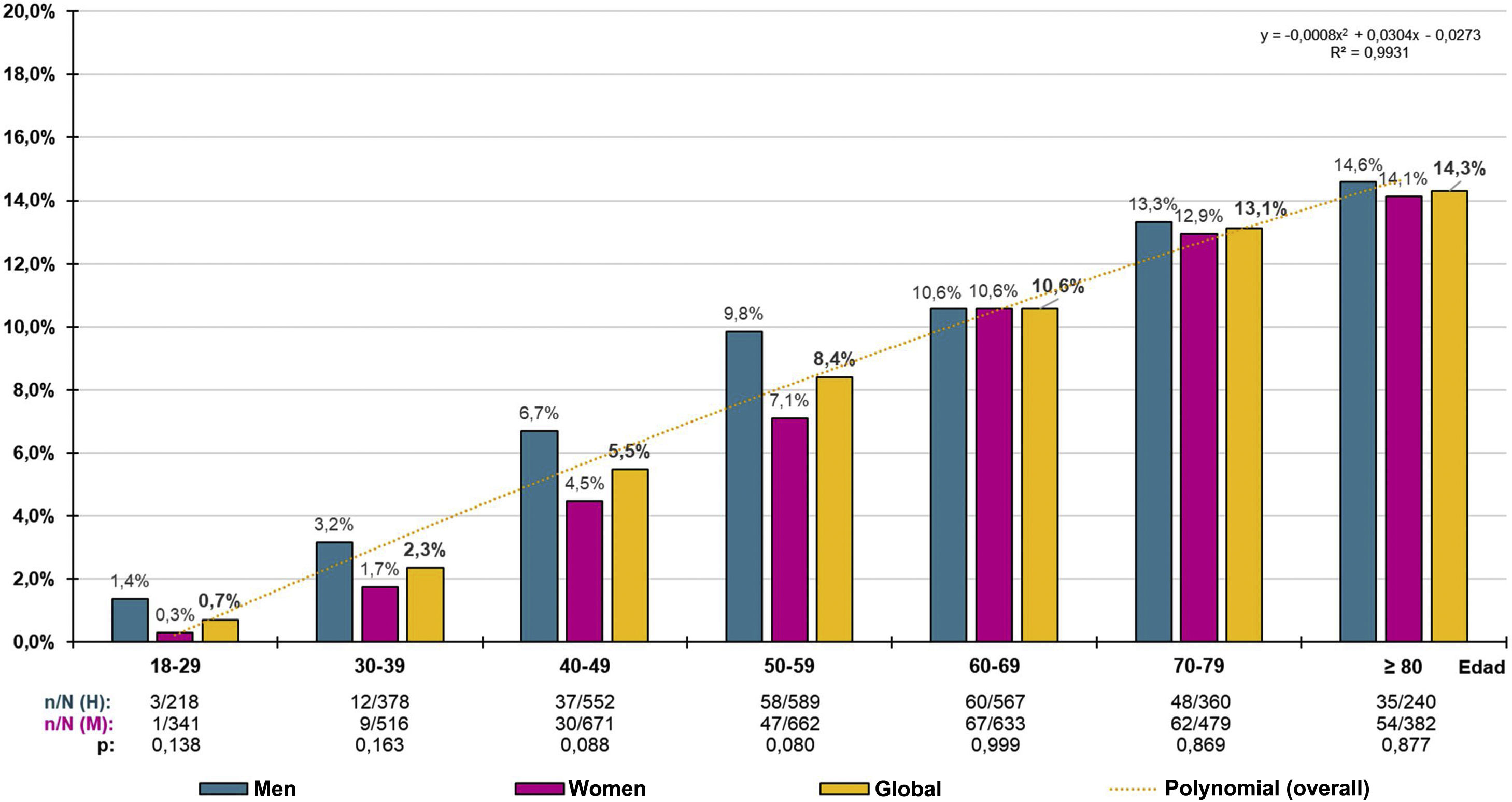

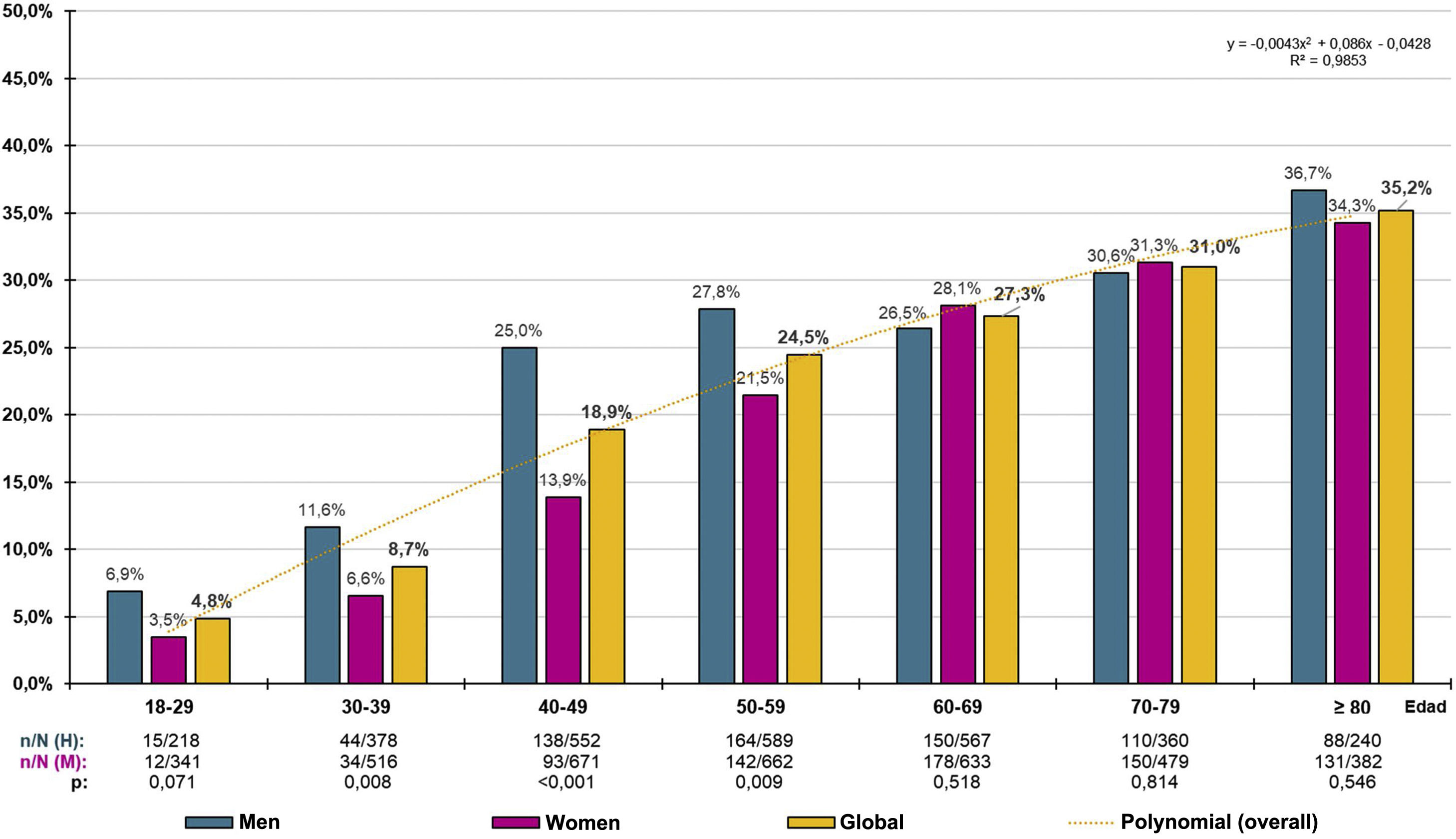

The crude prevalence of PRED-SED was 7.94% (95% CI: 7.29%–8.59%), with the difference between males (8.71% [95%CI: 7.68%–9.74%]) and females (7.33% [95%CI: 6.49%–8.17%]) and was significant (P = .040). The crude prevalence of PRED-ADA was 21.99% (95%CI: 20.99%–22.99%), and the difference between males (24.41% [95%CI: 22.85%–25.97%]) and females (20.09% [95%CI: 18.00%–21.38%]) was significant (P < .001). The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence rate of PRED-SED was 6.63% (7.18% in men and 6.27% in women). The adjusted prevalence rate of PRED-ADA was 19.11% (21.26% in men and 17.63% in women). The prevalence rates by ten-year age groups in males, females and overall, for PRED-SED and PRED-ADA are shown in Figs. 1 and 2 respectively.

The distribution of PRED-SED prevalence increased with age (R² = .993), according to the polynomial function y = −.0008x2 + .0304x − .0273, with no significant differences between men and women (Fig. 1). Similarly, the distribution of PRED-ADA prevalence increased with age (R² = .985), according to the polynomial function y = −.0043x2 + .0086x − .0428, with no significant differences between men and women, except in the age groups between 30 and 59 years, where prevalence rates were significantly higher in men than in women (Fig. 2).

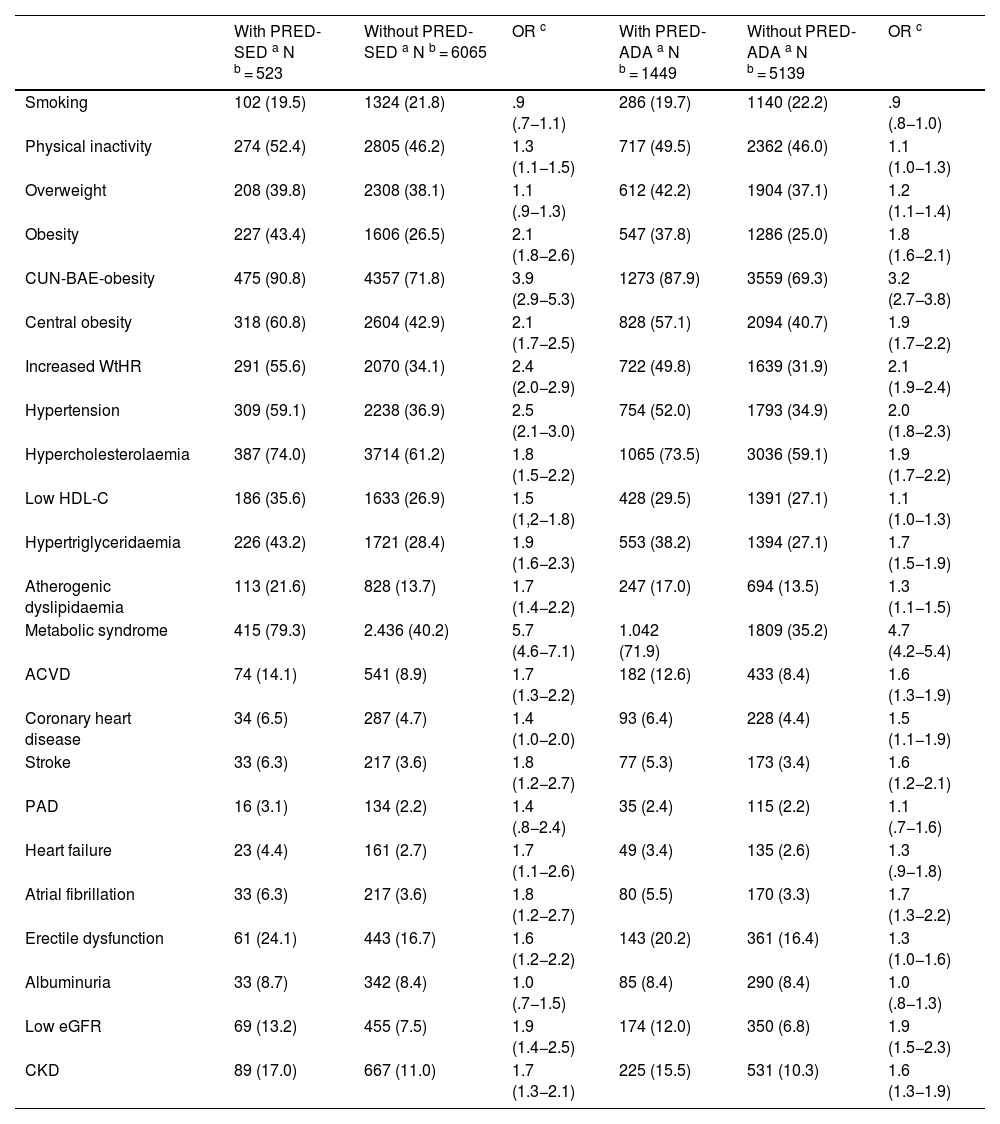

All parameters assessed were significantly higher in the populations with prediabetes than in those without prediabetes, except HDL-C and eGFR concentrations, which were lower in the populations with prediabetes, and aspartate aminotransferase and albuminuria concentrations, for which the differences were not significant (Tables 1 and 2). The ORs of the associated comorbidities between the populations with and without prediabetes are shown in Table 3.

Comorbidities and CVRF in populations with and without sin prediabetes.

| With PRED-SED a N b = 523 | Without PRED-SED a N b = 6065 | OR c | With PRED-ADA a N b = 1449 | Without PRED-ADA a N b = 5139 | OR c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 102 (19.5) | 1324 (21.8) | .9 (.7−1.1) | 286 (19.7) | 1140 (22.2) | .9 (.8−1.0) |

| Physical inactivity | 274 (52.4) | 2805 (46.2) | 1.3 (1.1−1.5) | 717 (49.5) | 2362 (46.0) | 1.1 (1.0−1.3) |

| Overweight | 208 (39.8) | 2308 (38.1) | 1.1 (.9−1.3) | 612 (42.2) | 1904 (37.1) | 1.2 (1.1−1.4) |

| Obesity | 227 (43.4) | 1606 (26.5) | 2.1 (1.8−2.6) | 547 (37.8) | 1286 (25.0) | 1.8 (1.6−2.1) |

| CUN-BAE-obesity | 475 (90.8) | 4357 (71.8) | 3.9 (2.9−5.3) | 1273 (87.9) | 3559 (69.3) | 3.2 (2.7−3.8) |

| Central obesity | 318 (60.8) | 2604 (42.9) | 2.1 (1.7−2.5) | 828 (57.1) | 2094 (40.7) | 1.9 (1.7−2.2) |

| Increased WtHR | 291 (55.6) | 2070 (34.1) | 2.4 (2.0−2.9) | 722 (49.8) | 1639 (31.9) | 2.1 (1.9−2.4) |

| Hypertension | 309 (59.1) | 2238 (36.9) | 2.5 (2.1−3.0) | 754 (52.0) | 1793 (34.9) | 2.0 (1.8−2.3) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 387 (74.0) | 3714 (61.2) | 1.8 (1.5−2.2) | 1065 (73.5) | 3036 (59.1) | 1.9 (1.7−2.2) |

| Low HDL-C | 186 (35.6) | 1633 (26.9) | 1.5 (1,2−1.8) | 428 (29.5) | 1391 (27.1) | 1.1 (1.0−1.3) |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 226 (43.2) | 1721 (28.4) | 1.9 (1.6−2.3) | 553 (38.2) | 1394 (27.1) | 1.7 (1.5−1.9) |

| Atherogenic dyslipidaemia | 113 (21.6) | 828 (13.7) | 1.7 (1.4−2.2) | 247 (17.0) | 694 (13.5) | 1.3 (1.1−1.5) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 415 (79.3) | 2.436 (40.2) | 5.7 (4.6−7.1) | 1.042 (71.9) | 1809 (35.2) | 4.7 (4.2−5.4) |

| ACVD | 74 (14.1) | 541 (8.9) | 1.7 (1.3−2.2) | 182 (12.6) | 433 (8.4) | 1.6 (1.3−1.9) |

| Coronary heart disease | 34 (6.5) | 287 (4.7) | 1.4 (1.0−2.0) | 93 (6.4) | 228 (4.4) | 1.5 (1.1−1.9) |

| Stroke | 33 (6.3) | 217 (3.6) | 1.8 (1.2−2.7) | 77 (5.3) | 173 (3.4) | 1.6 (1.2−2.1) |

| PAD | 16 (3.1) | 134 (2.2) | 1.4 (.8−2.4) | 35 (2.4) | 115 (2.2) | 1.1 (.7−1.6) |

| Heart failure | 23 (4.4) | 161 (2.7) | 1.7 (1.1−2.6) | 49 (3.4) | 135 (2.6) | 1.3 (.9−1.8) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 33 (6.3) | 217 (3.6) | 1.8 (1.2−2.7) | 80 (5.5) | 170 (3.3) | 1.7 (1.3−2.2) |

| Erectile dysfunction | 61 (24.1) | 443 (16.7) | 1.6 (1.2−2.2) | 143 (20.2) | 361 (16.4) | 1.3 (1.0−1.6) |

| Albuminuria | 33 (8.7) | 342 (8.4) | 1.0 (.7−1.5) | 85 (8.4) | 290 (8.4) | 1.0 (.8−1.3) |

| Low eGFR | 69 (13.2) | 455 (7.5) | 1.9 (1.4−2.5) | 174 (12.0) | 350 (6.8) | 1.9 (1.5−2.3) |

| CKD | 89 (17.0) | 667 (11.0) | 1.7 (1.3−2.1) | 225 (15.5) | 531 (10.3) | 1.6 (1.3−1.9) |

ACVD: Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; Albuminuria: albumin-to-creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g; Atherogenic dyslipidaemia: hypertriglyceridaemia and low HDL-C; Central obesity: abdominal circumference ≥ 102 cm (men); ≥88 cm (women); CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; CUN-BAE: Adiposity or body fat index (Clínica Universitaria de Navarra–Body Adiposity Estimator); CUN-BAE-obesity: >25% (men); >35% (women); CVRF: Cardiovascular Risk Factors; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate according to CKD-EPI < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2; Hypercholesterolaemia: total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL; Hypertriglyceridaemia: triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; Increased WtHR: Waist to height ratio ≥ .6; Low HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol < 40 mg/dL (men) < 50 mg/dL (women); Obesity: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2; Overweight: BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2; PAD: Peripheral Arterial Disease; Physical inactivity: physical activity < 150 min/week; PRED-ADA: Prediabetes according to the American Diabetes Association (FPG: 100–125 mg/dL or HbA1c: 5.7%–6,4%); PRED-SED: Prediabetes according to the Spanish Diabetes Society (FPG: 110–125 mg/dL or HbA1c: 6.0%–6.4%); Smoking: smoking any amount of cigarettes or tobacco in the last month.

The percentages of the study subjects with low, moderate, high, and very high CVR in the PRED-SED population were 7.46% (95%CI: 5.21–9.71), 23.90% (95% CI: 20.25–27.56), 29.83% (95% CI: 25.91–33.75), and 38.81% (95% CI: 34.64–42.99) respectively. The percentages of study subjects with low, moderate, high, and very high CVR in the PRED-ADA population were 11.04% (95% CI: 9.43–12.66), 27.26% (95% CI: 24.97–29.55), 28.02% (95% CI: 25.71–30.33), and 33.68% (95% CI: 31.24–36.11) respectively.

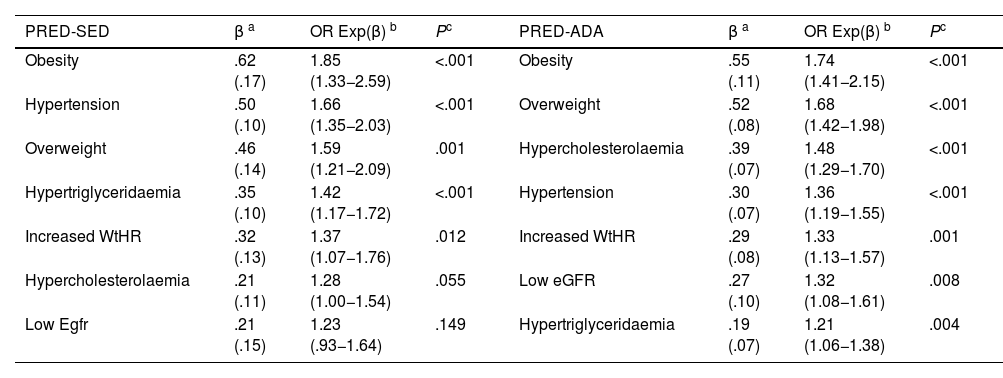

The multivariate analysis showed that HBP, HTG, overweight, obesity, and increased WtHR were the CVRFs, and comorbidities independently associated with PRED-SED. In addition to these variables, hypercholesterolaemia and low eGFR were independently associated with PRED-ADA (Table 4).

Multivariate analysis of the effect of comorbidities and CVRFs on prediabetes.

| PRED-SED | β a | OR Exp(β) b | Pc | PRED-ADA | β a | OR Exp(β) b | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity | .62 (.17) | 1.85 (1.33−2.59) | <.001 | Obesity | .55 (.11) | 1.74 (1.41−2.15) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | .50 (.10) | 1.66 (1.35−2.03) | <.001 | Overweight | .52 (.08) | 1.68 (1.42−1.98) | <.001 |

| Overweight | .46 (.14) | 1.59 (1.21−2.09) | .001 | Hypercholesterolaemia | .39 (.07) | 1.48 (1.29−1.70) | <.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | .35 (.10) | 1.42 (1.17−1.72) | <.001 | Hypertension | .30 (.07) | 1.36 (1.19−1.55) | <.001 |

| Increased WtHR | .32 (.13) | 1.37 (1.07−1.76) | .012 | Increased WtHR | .29 (.08) | 1.33 (1.13−1.57) | .001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | .21 (.11) | 1.28 (1.00−1.54) | .055 | Low eGFR | .27 (.10) | 1.32 (1.08−1.61) | .008 |

| Low Egfr | .21 (.15) | 1.23 (.93−1.64) | .149 | Hypertriglyceridaemia | .19 (.07) | 1.21 (1.06−1.38) | .004 |

CVRF: Cardiovascular Risk Factors; Hypercholesterolaemia: total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL; Hypertriglyceridaemia: triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; Increased WtHR: Weight to height ratio ≥ .6; Low eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (CKD-EPI); Obesity: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2; Overweight: BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2; PRED-ADA: Prediabetes according to the American Diabetes Association (FPG: 100–125 mg/dL or HbA1c: 5.7%–6.4%); PRED-SED: Prediabetes according to the Spanish Diabetes Society (FPG: 110–125 mg/dL or HbA1c: 6.0%–6.4%).

Prediabetes represents a gap between normal glycaemic status and DM, which implies an inherent disease risk. If progression from normoglycaemia to DM may take several years, prediabetes could be a detectable clinical state, which would help identify subjects at increased risk of developing DM and episodes of ACVD.4 However, the course of subjects with prediabetes is highly variable. Without any intervention, some individuals may progress to DM, others may remain with the condition for the rest of their lives and others may return to a state of normoglycaemia.23

The scientific societies show criteria heterogeneity in defining prediabetes, resulting in varying prevalence rates of the condition. The ADA16 includes IFG within the term prediabetes defined as FPG concentrations between 100 and 125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/l), and HbA1c values between 5.7% and 6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol). On the other hand, the World Health Organisation24 (WHO) considers hyperglycaemia to be FPG concentrations between 110 and 125 mg/dL (6.1–6.9 mmol/l), and the guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence25 (NICE) and the Australian Diabetes Society26 consider HbA1c values between 6.0% and 6.4% (42–47 mmol/mol) to be prediabetes. The SED,17 in consensus with other Spanish scientific societies, follow the WHO24 and NICE25 criteria for diabetes, both criteria also proposed by the Canadian Diabetes Society.27

In the SIMETAP-PRED study, the prevalence of prediabetes was three times higher using the ADA16 diagnostic criteria than using the SED17 criteria, most likely because the PRED-ADA population has broader FPG and/or HbA1c values than the PRED-SED population. Age-group-specific prevalence rates in both populations increased precisely with age probably due to the progressive accumulation of cardiometabolic, cardiovascular and renal factors related to prediabetes. Adjusted prevalence rates of prediabetes were higher in men than in women, similar to DM,14,28 showing larger differences according to ADA16 criteria (21.3% vs. 17.6%) than those of the SED17 (7.2% vs. 6.3%). On the other hand, the mean age of the PRE-ADA population was found to be 2.4 years less than the PRE-SED population and the proportion of men with prediabetes was significantly higher in the 30–59 age groups of the PRE-ADA population. Therefore, using the broader ADA16 diagnostic criteria, the detection of prediabetes would be earlier and include a higher proportion of subjects, especially males.

The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence rates in the SIMETAP-PRED study were lower than those found in other studies conducted in other countries,26,29–35 either using ADA16 or SED17 criteria. Compared with other studies conducted in Spain,36,37 the adjusted prevalence rate of the present study was higher when ADA criteria were used16,36 and lower when SED criteria were used.17,37 The prevalence was similar to that of the PREDIMERC38 study conducted in the Community of Madrid. The differences could be because the SIMETAP-PRED study did not perform glucose overload to determine glucose intolerance, because most of the studies are based on health surveys,29–35 and because the age range of the population studied was broader compared to the other comparison studies.

It is known that prediabetes is a state of insulin resistance3 that is associated with obesity, increased abdominal circumference, hypertension, and atherogenic dyslipidaemia,4–6,16 and is considered a factor that increases the risk of developing DM1,2 and ACVD.8–10,16 BMI is not considered to be a good indicator in subjects of short stature, advanced age, muscular, with water retention or pregnant women,39 as it does not provide information on the distribution of body fat or differentiate between fat and lean mass.40 Therefore, the American Associations of Endocrinology41 and the Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity (SEEDO)42 recommend other anthropometric indicators such as abdominal circumference, WtHR, or algorithms to estimate fat mass such as CUN-BAE.18 The present study showed that overweight, obesity, and increased WtHR were independent factors associated with prediabetes. Although CUN-BAE-obesity was not included in the multivariate analysis because it is a complex variable that includes other variables already analysed, it was the second variable showing the strongest association with prediabetes after MS.19

The prevalence rates of HBP, hypercholesterolaemia, low eGFR, and albuminuria in the PRED-ADA population of the SIMETAP-PRED study were more frequent than in the prediabetes group of the NHANES survey,6 probably because the mean age of the population of the present study was 10 years older (62 vs. 52 years) than that of the NHANES survey.6

HBP was an independent factor showing a significant association with prediabetes in both groups; it was slightly lower in the PRED-ADA group than in the PRED-SED group, probably because the PRE-ADA population had a higher percentage of people aged 40–60 years where the prevalence of HBP is lower.

The variables hypercholesterolaemia, HTG, low HDL-C and atherogenic dyslipidaemia were also associated with prediabetes, and HTG was independently associated with PRED-SED and PRED-ADA, and hypercholesterolaemia with PRED-ADA. Two recent studies have also shown some of these relationships, with PRED-ADA, not PRED-SED, as a factor independently associated with HTG and atherogenic dyslipidaemia.43,44 Assuming that prediabetes is considered within the concept of MS,19 the associations of central obesity, HBP, HTG, and low HDL-C with PRED-SED and PRED-ADA could also explain why MS19 was the variable with the strongest association with both groups of prediabetes.

With respect to renal function, no association was found between albuminuria and prediabetes, although an association was observed with low eGFR in both groups, which was shown to be an independent PRED-ADA risk factor.

The variables of ACVD and its components, heart failure, and erectile dysfunction showed moderate to slight association, although none were independently associated with prediabetes. This would support the assertion that not all people with prediabetes without ACVD are at elevated CVR,9,11 and that they need to be assessed for CVR in the same way as the general population.11 On the other hand, the SIMETAP-PRED study shows that the percentage of patients at high or very high CVR in the PRED-SED and PRED-ADA populations was 68.6% and 61.7% respectively, and that there are significant differences in prevalence rates of coronary heart disease and stroke between the populations with and without prediabetes, and therefore some signs of arteriosclerotic vascular damage could be detected and its progression prevented if there is early intervention on its predisposing factors.45

A limitation of the present study was the inability to determine causality or estimate incidence rates because it was a cross-sectional study. Other limitations were related to possible under-diagnosis as oral glucose overload was not performed ad hoc to determine glucose intolerance in patients without DM and there was no information on HbA1c for 18.9% of the study population, although all of them could be diagnosed with prediabetes using the respective FPG criteria. Furthermore, by protocol, pregnant women, terminally ill, institutionalised, or cognitively impaired patients were not included in the study. The main strengths of the present study were the population-based random selection, a large sample including the entire adult population aged 18–102 years, and the assessment of the possible association with numerous cardiometabolic, cardiovascular, and renal variables.

Carbohydrate metabolism abnormalities can be detected up to 10 years before the diagnosis of DM,1 and therefore early detection of prediabetes would allow measures to be implemented to prevent DM onset by controlling weight, blood pressure, and dyslipidaemia. The less stringent ADA16 diagnostic criteria, with a wider range of FPG and HbA1c values, are possibly the most appropriate to achieve these goals. In summary, the earlier detection of prediabetes and the greater association of cardiometabolic and renal factors with the PRED-ADA parameters could tip the balance in their favour when deciding between SED17 or ADA16 criteria.

The SIMETAP-PRED study shows how prediabetes is strongly influenced by age, and therefore its prevalence should always be documented with age-adjusted rates to enable comparison with other populations. However, it also shows a high prevalence in the population over 60 years of age and more population-based epidemiological studies are needed. The high prevalence of prediabetes has an impact on the socio-economic and health burden by increasing the risk of DM and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Assessment of the prevalence of prediabetes is very important to plan and optimise available health resources and to improve medical care through the implementation of cardiovascular and DM risk prevention measures, such as effective lifestyle changes in patients with prediabetes.

ConclusionsThe age-adjusted prevalence of prediabetes was 6.6% using the SED criteria and 19.1% using the ADA criteria, increasing with age, and slightly higher in men than in women. A total of 68.6% of the PRED-SED population and 61.7% of the PRED-ADA population were at high or very high CVR. In the population studied in the SIMETAP-PRED study, the cardiometabolic factors of overweight, obesity, increased WtHR, HBP and HTG were independently associated with prediabetes diagnosed with the SED17 or ADA16 criteria. In addition to these factors, hypercholesterolaemia and low eGFR are independently associated with prediabetes diagnosed with ADA criteria.16 The increased association with cardiometabolic, cardiovascular, and renal factors, and the increased detection of prediabetes following ADA criteria,16 would improve its early diagnosis and enable early intervention on all these factors, and thus reduce the progression of prediabetes to DM as well as the risk of ACVD in patients with prediabetes.

Research Ethics CommitteeComisión de Investigación de la Gerencia Adjunta de Planificación y Calidad. (Research Committee of the Planning and Quality Management Office).

Primary Care Management. Madrid Health Service (SERMAS).

FundingFunding for the SIMETAP study (Grant Code: 05/2010RS) was approved in accordance with Order 472/2010, of 16 September, of the Regional Ministry of Health, approving the regulatory bases and the call for grants for 2010 from the “Pedro Laín Entralgo” Agency for Training, Research and Health Studies of the Community of Madrid, for conducting research projects in the field of health outcomes in primary care.

Authors/collaboratorsEzequiel Arranz-Martínez and Antonio Ruiz-García share first author status.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the following doctors who participated in the SIMETAP study research group: Abad Schilling C, Adrián Sanz M, Aguilera Reija P, Alcaraz Bethencourt A, Alonso Roca R, Álvarez Benedicto R, Arranz Martínez E, Arribas Álvaro P, Baltuille Aller MC, Barrios Rueda E, Benito Alonso E, Berbil Bautista ML, Blanco Canseco JM, Caballero Ramírez N, Cabello Igual P, Cabrera Vélez R, Calderín Morales MP, Capitán Caldas M, Casaseca Calvo TF, Cique Herráinz JA, Ciria de Pablo C, Chao Escuer P, Dávila Blázquez G, de la Peña Antón N, de Prado Prieto L, del Villar Redondo MJ, Delgado Rodríguez S, Díez Pérez MC, Durán Tejada MR, Escamilla Guijarro N, Escrivá Ferrairó RA, Fernández Vicente T, Fernández-Pacheco Vila D, Frías Vargas MJ, García Álvarez JC, García Fernández ME, García Alcañiz MP, García Granado MD, García Pliego RA, García Redondo MR, García Villasur MP, Gómez Díaz E, Gómez Fernández O, González Escobar P, González-Posada Delgado JA, Gutiérrez Sánchez I, Hernández Beltrán MI, Hernández de Luna MC, Hernández López RM, Hidalgo Calleja Y, Holgado Catalán MS, Hombrados Gonzalo MP, Hueso Quesada R, Ibarra Sánchez AM, Iglesias Quintana JR, Íscar Valenzuela I, Iturmendi Martínez N, Javierre Miranda AP, López Uriarte B, Lorenzo Borda MS, Luna Ramírez S, Macho del Barrio AI, Magán Tapia P, Marañón Henrich N, Mariño Suárez JE, Martín Calle MC, Martín Fernández AI, Martínez Cid de Rivera E, Martínez Irazusta J, Migueláñez Valero A, Minguela Puras ME, Montero Costa A, Mora Casado C, Morales Cobos LE, Morales Chico MR, Moreno Fernández JC, Moreno Muñoz MS, Palacios Martínez D, Pascual Val T, Pérez Fernández M, Pérez Muñoz R, Plata Barajas MT, Pleite Raposo R, Prieto Marcos M, Quintana Gómez JL, Redondo de Pedro S, Redondo Sánchez M, Reguillo Díaz J, Remón Pérez B, Revilla Pascual E, Rey López AM, Ribot Catalá C, Rico Pérez MR, Rivera Teijido M, Rodríguez Cabanillas R, Rodríguez de Cossío A, Rodríguez de Mingo E, Rodríguez AO, Rosillo González A, Rubio Villar M, Ruiz Díaz L, Ruiz García A, Sánchez Calso A, Sánchez Herráiz M, Sánchez Ramos MC, Sanchidrián Fernández PL, Sandín de Vega E, Sanz Pozo B, Sanz Velasco C, Sarriá Sánchez MT, Simonaggio Stancampiano P, Tello Meco I, Vargas-Machuca Cabañero C, Velazco Zumarrán JL, Vieira Pascual MC, Zafra Urango C, Zamora Gómez MM, Zarzuelo Martín N.

We would like to thank the following doctors who participated in the SIMETAP study research group for their hard work and dedication: Abad Schilling C, Adrián Sanz M, Aguilera Reija P, Alcaraz Bethencourt A, Alonso Roca R, Álvarez Benedicto R, Arranz Martínez E, Arribas Álvaro P, Baltuille Aller MC, Barrios Rueda E, Benito Alonso E, Berbil Bautista ML, Blanco Canseco JM, Caballero Ramírez N, Cabello Igual P, Cabrera Vélez R, Calderín Morales MP, Capitán Caldas M, Casaseca Calvo TF, Cique Herráinz JA, Ciria de Pablo C, Chao Escuer P, Dávila Blázquez G, de la Peña Antón N, de Prado Prieto L, del Villar Redondo MJ, Delgado Rodríguez S, Díez Pérez MC, Durán Tejada MR, Escamilla Guijarro N, Escrivá Ferrairó RA, Fernández Vicente T, Fernández-Pacheco Vila D, Frías Vargas MJ, García Álvarez JC, García Fernández ME, García Alcañiz MP, García Granado MD, García Pliego RA, García Redondo MR, García Villasur MP, Gómez Díaz E, Gómez Fernández O, González Escobar P, González-Posada Delgado JA, Gutiérrez Sánchez I, Hernández Beltrán MI, Hernández de Luna MC, Hernández López RM, Hidalgo Calleja Y, Holgado Catalán MS, Hombrados Gonzalo MP, Hueso Quesada R, Ibarra Sánchez AM, Iglesias Quintana JR, Íscar Valenzuela I, Iturmendi Martínez N, Javierre Miranda AP, López Uriarte B, Lorenzo Borda MS, Luna Ramírez S, Macho del Barrio AI, Magán Tapia P, Marañón Henrich N, Mariño Suárez JE, Martín Calle MC, Martín Fernández AI, Martínez Cid de Rivera E, Martínez Irazusta J, Migueláñez Valero A, Minguela Puras ME, Montero Costa A, Mora Casado C, Morales Cobos LE, Morales Chico MR, Moreno Fernández JC, Moreno Muñoz MS, Palacios Martínez D, Pascual Val T, Pérez Fernández M, Pérez Muñoz R, Plata Barajas MT, Pleite Raposo R, Prieto Marcos M, Quintana Gómez JL, Redondo de Pedro S, Redondo Sánchez M, Reguillo Díaz J, Remón Pérez B, Revilla Pascual E, Rey López AM, Ribot Catalá C, Rico Pérez MR, Rivera Teijido M, Rodríguez Cabanillas R, Rodríguez de Cossío A, Rodríguez De Mingo E, Rodríguez AO, Rosillo González A, Rubio Villar M, Ruiz Díaz L, Ruiz García A, Sánchez Calso A, Sánchez Herráiz M, Sánchez Ramos MC, Sanchidrián Fernández PL, Sandín de Vega E, Sanz Pozo B, Sanz Velasco C, Sarriá Sánchez MT, Simonaggio Stancampiano P, Tello Meco I, Vargas-Machuca Cabañero C, Velazco Zumarrán JL, Vieira Pascual MC, Zafra Urango C, Zamora Gómez MM, Zarzuelo Martín N.

Please cite this article as: Arranz-Martínez E, Ruiz-García A, García Álvarez JC, Fernández Vicente T, Iturmendi Martínez N, Rivera-Teijido M. Prevalencia de prediabetes y asociación con factores cardiometabólicos y renales. Estudio SIMETAP-PRED. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2022;73:193–204.