The current paradigm in the nutrition sciences states that the basic nutritional unit is not the nutrients, but the foods that contain them (oils, nuts, dairy products, eggs, red or processed meats, etc.). These act as a food matrix in which the different nutrients synergistically or antagonistically modulate their effects on the various metabolic pathways determining health and disease. Food is not based on nutrients or isolated foods but on complex mixtures of one and the other that are part of a specific food pattern, a concept that has been targeted as the most pertinent to evaluate the associations between nutrition and health or disease.

This document presents a summary of the available evidence on the relationship between different foods and cardiovascular health, and offers simple recommendations to be implemented in the dietary advice offered by the health professional.

El actual paradigma en las ciencias de la nutrición establece que la unidad nutricional básica no son los nutrientes, sino los alimentos que los contienen (aceites, frutos secos, productos lácteos, huevos, carnes rojas o procesadas, etc.), que actúan como matriz alimentaria en la que los diferentes nutrientes modulan sinérgica o antagónicamente sus efectos sobre diversas vías metabólicas determinantes para la salud y la enfermedad. La alimentación no se basa en nutrientes ni en alimentos aislados sino en complejas mezclas de unos y otros que forman parte de un patrón alimentario concreto, concepto que se ha señalado como el más pertinente para evaluar las asociaciones entre nutrición y salud o enfermedad.

Este documento resume las evidencias disponibles sobre la relación existente entre los diferentes alimentos y la salud cardiovascular, y ofrece recomendaciones sencillas para ser implementadas en el consejo dietético que se ofrezca por parte del profesional sanitario.

Diet and physical activity are the cornerstones of a healthy lifestyle and the essential foundations for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. An essential part of the work of primary care (PC) is to provide people with clear and practicable advice that they can use as a tool to improve their health. The aim of this document is to provide an update on our knowledge of the main food groups, with guidelines to help healthcare professionals incorporate the latest scientific evidence into clinical practice. We also define simple recommendations for the people receiving advice.

The role of diet and the benefits of a Mediterranean-type eating pattern in cardiovascular risk have been a focus of interest among healthcare professionals for many years. In the Seven Countries Study, they found that, in populations whose total fat intake in relation to the total calorific value of the diet was similar, the type of dietary fat was one of the determining factors in the different cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rates from one country to another, and explained why these rates are lower in southern Europe than in northern Europe or the United States.1

Other prospective cohort studies show the suitability of the Mediterranean diet in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and in the reduction of cardiovascular mortality rates. The EPIC2 and HALE3 studies have confirmed the epidemiological association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and lower mortality rates from any cause.

The Lyon Diet Heart Study was the first intervention study to conclude that the Mediterranean diet pattern was an effective non-pharmacological strategy in secondary prevention to reduce coronary clinical events in patients who had survived a myocardial infarction; this benefit was independent of the lipid profile, as no differences in cholesterol levels were observed between the control group and the group randomised to the Mediterranean-type diet.4 More recently, the PREDIMED study conducted in Spain in individuals at high cardiovascular risk, but without a history of ischaemic vascular disease, showed that a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra virgin olive oil or nuts (hazelnuts, almonds and walnuts) achieved a 30% reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular disease.5 The fat content in this diet exceeds 35% of the total calorie intake, mainly resulting from the unsaturated fat provided by the nuts and extra virgin olive oil, as opposed to the low-fat diet traditionally recommended and used in the control group.

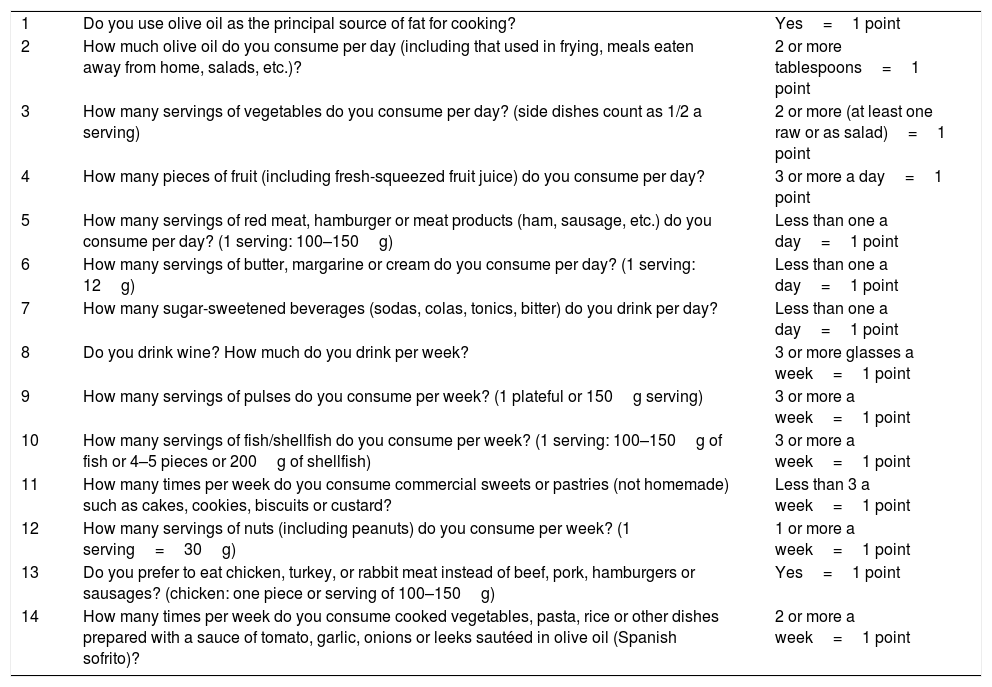

It would seem therefore that a Mediterranean-type dietary pattern is appropriate as an effective alternative for cardiovascular prevention. Table 1 shows the 14-point diet survey used in the PREDIMED study, which enables a simple individual assessment of degree of adherence to the Mediterranean diet. The higher the score, the better the adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

Individual assessment of degree of adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

| 1 | Do you use olive oil as the principal source of fat for cooking? | Yes=1 point |

| 2 | How much olive oil do you consume per day (including that used in frying, meals eaten away from home, salads, etc.)? | 2 or more tablespoons=1 point |

| 3 | How many servings of vegetables do you consume per day? (side dishes count as 1/2 a serving) | 2 or more (at least one raw or as salad)=1 point |

| 4 | How many pieces of fruit (including fresh-squeezed fruit juice) do you consume per day? | 3 or more a day=1 point |

| 5 | How many servings of red meat, hamburger or meat products (ham, sausage, etc.) do you consume per day? (1 serving: 100–150g) | Less than one a day=1 point |

| 6 | How many servings of butter, margarine or cream do you consume per day? (1 serving: 12g) | Less than one a day=1 point |

| 7 | How many sugar-sweetened beverages (sodas, colas, tonics, bitter) do you drink per day? | Less than one a day=1 point |

| 8 | Do you drink wine? How much do you drink per week? | 3 or more glasses a week=1 point |

| 9 | How many servings of pulses do you consume per week? (1 plateful or 150g serving) | 3 or more a week=1 point |

| 10 | How many servings of fish/shellfish do you consume per week? (1 serving: 100–150g of fish or 4–5 pieces or 200g of shellfish) | 3 or more a week=1 point |

| 11 | How many times per week do you consume commercial sweets or pastries (not homemade) such as cakes, cookies, biscuits or custard? | Less than 3 a week=1 point |

| 12 | How many servings of nuts (including peanuts) do you consume per week? (1 serving=30g) | 1 or more a week=1 point |

| 13 | Do you prefer to eat chicken, turkey, or rabbit meat instead of beef, pork, hamburgers or sausages? (chicken: one piece or serving of 100–150g) | Yes=1 point |

| 14 | How many times per week do you consume cooked vegetables, pasta, rice or other dishes prepared with a sauce of tomato, garlic, onions or leeks sautéed in olive oil (Spanish sofrito)? | 2 or more a week=1 point |

Score: add up all the points (right column).

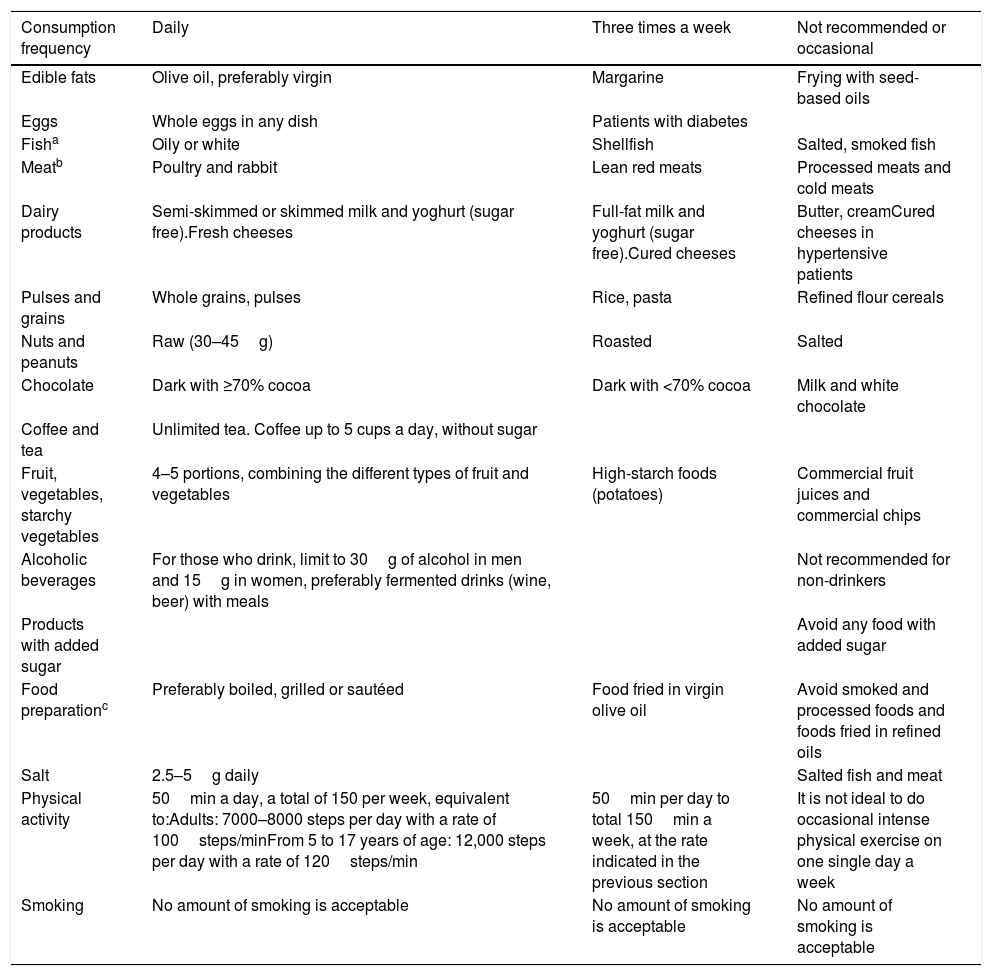

The document we have based this work on, “Recomendaciones de la SEA 2018” (Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis [Spanish Atherosclerosis Society] 2018 Recommendations),6 is not on the traditional Mediterranean diet, because it does not simply limit itself to that concept, but in fact goes much further by incorporating recommendations based on new scientific evidence. One example is the consumption of red meat which, in the traditional Mediterranean pyramid, is considered as only for very occasional consumption. However here, in the light of recent findings, three to four times a week is considered to be safe. In fact, one interesting contribution of this document is the section “Recommendations for clinical practice”, illustrated with a very practical table of consumption frequency for foods, the conclusions of which are summarised in Table 2.

Recommended frequency in adherence to lifestyle components.

| Consumption frequency | Daily | Three times a week | Not recommended or occasional |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edible fats | Olive oil, preferably virgin | Margarine | Frying with seed-based oils |

| Eggs | Whole eggs in any dish | Patients with diabetes | |

| Fisha | Oily or white | Shellfish | Salted, smoked fish |

| Meatb | Poultry and rabbit | Lean red meats | Processed meats and cold meats |

| Dairy products | Semi-skimmed or skimmed milk and yoghurt (sugar free).Fresh cheeses | Full-fat milk and yoghurt (sugar free).Cured cheeses | Butter, creamCured cheeses in hypertensive patients |

| Pulses and grains | Whole grains, pulses | Rice, pasta | Refined flour cereals |

| Nuts and peanuts | Raw (30–45g) | Roasted | Salted |

| Chocolate | Dark with ≥70% cocoa | Dark with <70% cocoa | Milk and white chocolate |

| Coffee and tea | Unlimited tea. Coffee up to 5 cups a day, without sugar | ||

| Fruit, vegetables, starchy vegetables | 4–5 portions, combining the different types of fruit and vegetables | High-starch foods (potatoes) | Commercial fruit juices and commercial chips |

| Alcoholic beverages | For those who drink, limit to 30g of alcohol in men and 15g in women, preferably fermented drinks (wine, beer) with meals | Not recommended for non-drinkers | |

| Products with added sugar | Avoid any food with added sugar | ||

| Food preparationc | Preferably boiled, grilled or sautéed | Food fried in virgin olive oil | Avoid smoked and processed foods and foods fried in refined oils |

| Salt | 2.5–5g daily | Salted fish and meat | |

| Physical activity | 50min a day, a total of 150 per week, equivalent to:Adults: 7000–8000 steps per day with a rate of 100steps/minFrom 5 to 17 years of age: 12,000 steps per day with a rate of 120steps/min | 50min per day to total 150min a week, at the rate indicated in the previous section | It is not ideal to do occasional intense physical exercise on one single day a week |

| Smoking | No amount of smoking is acceptable | No amount of smoking is acceptable | No amount of smoking is acceptable |

Alternate meat, an important source of animal proteins, with fish and consume one of these options a day. White meat is better than red meat.

Dishes seasoned with tomato sauce, garlic, onion or leek cooked with virgin olive oil (Spanish sofrito) can be eaten daily.

Source: Pérez-Jiménez et al.6

At present, the main limitation of studies on human nutrition is the fact that there are so few intervention studies on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The result is that most of the advice is based on large-cohort follow-up observational studies, or clinical trials analysing the relationship between lifestyle and the multiple surrogate markers of cardiovascular risk, whether clinical (body weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, etc.) or biochemical (lipid profile, blood glucose and inflammatory markers). This is a limitation due to the differences in the methodology used in the studies.

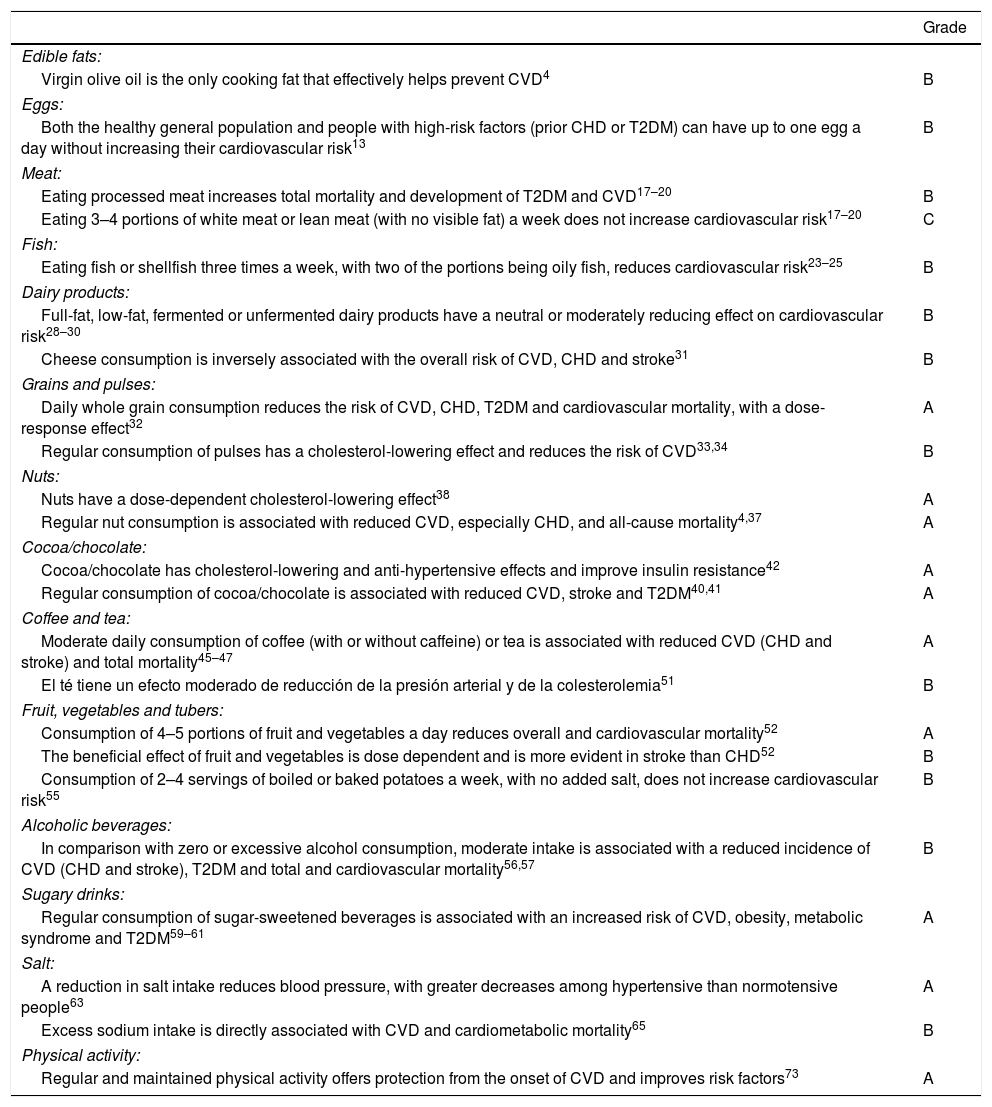

In an effort to grade the level of evidence on food consumption and cardiovascular risk, we set out the recommendations for each of the food groups analysed in Table 36: A evidence, based on clinical trials and meta-analyses which incorporate quality criteria in their analyses; B evidence, supported by prospective cohort studies and case-control studies; and C evidence, justified by consensus and expert opinions or based on extensive clinical practice.

Levels of evidence for the relationship between lifestyle components and cardiovascular risk.

| Grade | |

|---|---|

| Edible fats: | |

| Virgin olive oil is the only cooking fat that effectively helps prevent CVD4 | B |

| Eggs: | |

| Both the healthy general population and people with high-risk factors (prior CHD or T2DM) can have up to one egg a day without increasing their cardiovascular risk13 | B |

| Meat: | |

| Eating processed meat increases total mortality and development of T2DM and CVD17–20 | B |

| Eating 3–4 portions of white meat or lean meat (with no visible fat) a week does not increase cardiovascular risk17–20 | C |

| Fish: | |

| Eating fish or shellfish three times a week, with two of the portions being oily fish, reduces cardiovascular risk23–25 | B |

| Dairy products: | |

| Full-fat, low-fat, fermented or unfermented dairy products have a neutral or moderately reducing effect on cardiovascular risk28–30 | B |

| Cheese consumption is inversely associated with the overall risk of CVD, CHD and stroke31 | B |

| Grains and pulses: | |

| Daily whole grain consumption reduces the risk of CVD, CHD, T2DM and cardiovascular mortality, with a dose-response effect32 | A |

| Regular consumption of pulses has a cholesterol-lowering effect and reduces the risk of CVD33,34 | B |

| Nuts: | |

| Nuts have a dose-dependent cholesterol-lowering effect38 | A |

| Regular nut consumption is associated with reduced CVD, especially CHD, and all-cause mortality4,37 | A |

| Cocoa/chocolate: | |

| Cocoa/chocolate has cholesterol-lowering and anti-hypertensive effects and improve insulin resistance42 | A |

| Regular consumption of cocoa/chocolate is associated with reduced CVD, stroke and T2DM40,41 | A |

| Coffee and tea: | |

| Moderate daily consumption of coffee (with or without caffeine) or tea is associated with reduced CVD (CHD and stroke) and total mortality45–47 | A |

| El té tiene un efecto moderado de reducción de la presión arterial y de la colesterolemia51 | B |

| Fruit, vegetables and tubers: | |

| Consumption of 4–5 portions of fruit and vegetables a day reduces overall and cardiovascular mortality52 | A |

| The beneficial effect of fruit and vegetables is dose dependent and is more evident in stroke than CHD52 | B |

| Consumption of 2–4 servings of boiled or baked potatoes a week, with no added salt, does not increase cardiovascular risk55 | B |

| Alcoholic beverages: | |

| In comparison with zero or excessive alcohol consumption, moderate intake is associated with a reduced incidence of CVD (CHD and stroke), T2DM and total and cardiovascular mortality56,57 | B |

| Sugary drinks: | |

| Regular consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with an increased risk of CVD, obesity, metabolic syndrome and T2DM59–61 | A |

| Salt: | |

| A reduction in salt intake reduces blood pressure, with greater decreases among hypertensive than normotensive people63 | A |

| Excess sodium intake is directly associated with CVD and cardiometabolic mortality65 | B |

| Physical activity: | |

| Regular and maintained physical activity offers protection from the onset of CVD and improves risk factors73 | A |

CHD: coronary heart disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; CVD: cardiovascular disease; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus.

What follows is a brief analysis of the available evidence on the main food groups.

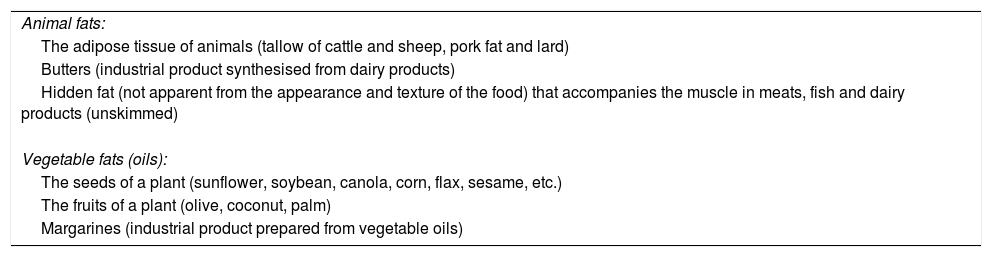

High-fat foodsDietary fat is a group of substances composed mainly of triglycerides (containing a molecule of glycerol to which 3 fatty acids are attached), cholesterol and other elements, such as phospholipids or sterols, and is characterised by being insoluble in aqueous solvents. Fats in the diet are either of animal or vegetable origin (Table 4). Animal fats are solid at room temperature, while oils (vegetable fats) are liquid. The length of the carbon chain and the number of double bonds (or degree of saturation) in the fatty acids influence the melting point of fats, which determines whether the fat is solid (tallow, lard, butter) or liquid (oil). The formation of a fluid structure at room temperature in the oils is thanks to the large amount of unsaturated fatty acids in their triglycerides, with double bonds giving greater flexibility to the carbon chain.

Source of fats in the diet.

| Animal fats: |

| The adipose tissue of animals (tallow of cattle and sheep, pork fat and lard) |

| Butters (industrial product synthesised from dairy products) |

| Hidden fat (not apparent from the appearance and texture of the food) that accompanies the muscle in meats, fish and dairy products (unskimmed) |

| Vegetable fats (oils): |

| The seeds of a plant (sunflower, soybean, canola, corn, flax, sesame, etc.) |

| The fruits of a plant (olive, coconut, palm) |

| Margarines (industrial product prepared from vegetable oils) |

Coconut and palm oils are very rich in saturated fatty acids, which have a single bond between each pair of carbon atoms, and all except the terminal carbon are bound to two hydrogen atoms, i.e. they are “saturated” with hydrogen. Saturated fatty acids (palmitic, myristic, lauric, stearic, butyric) are also present in fats of animal origin (lard, butter, cream). A high intake of these fatty acids causes a dose-dependent increase in serum levels of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C). However, substituting saturated fatty acids with monounsaturated fatty acids (present in olive oil and many nuts) or polyunsaturated fatty acids (in seed oils) reduces total cholesterol and LDL-C levels.7

In order to reduce saturated fat intake, not only fats of animal origin need to be restricted, but also vegetable oils derived from coconut and palm. We have to be aware that these oils can form part of the diet through “hidden fat” in bakery products, factory-baked goods and other processed foods. The labelling of these products states that they are made with vegetable fats, which makes the consumer believe they are heart-healthy, when in fact they can be quite the opposite if the proportion of saturated fat is high.

Most natural fats and oils contain only cis double bonds (spatially oriented on the same side of the molecule); however, the commercial production of solid vegetable fats gives rise to trans fatty acids, with double bonds in different spatial arrangement. Hydrogenation consists of adding hydrogen atoms to the unsaturated fatty acids in order to “solidify” the vegetable oils, transforming them into a spreading fat and prolonging their useful life by preventing their oxidation. Commercial snacks, pre-cooked meals and factory-baked goods are full of trans fatty acids, and they stand out because high consumption increases cardiovascular risk even more than saturated fatty acids. They have detrimental effects on the lipid profile, impair endothelial function and increase the production of inflammatory cytokines.8 Although in the past the process of making margarines produced trans fatty acids, current technology makes it possible to manufacture margarines practically devoid of trans and gives these solid fats a higher content in essential fatty acids of the series n-6 (linoleic acid) and n-3 (alpha-linolenic acid),8 enabling them to maintain the vitamin E bound to the fat fraction of the original oil.

If using oils high in polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as soybean and sunflower oil, they should be used cold as a dressing and not for cooking or frying, as heating causes oxygen free radical-mediated autoxidation, generating proinflammatory and atherogenic molecules.9 Due to their high content in polyunsaturates, margarines should also not be used for cooking or frying, only for spreading.

The main source of monounsaturated fatty acids (oleic acid) should be olive oil. Compared to polyunsaturated fatty acids, one beneficial effect of monounsaturates is their greater resistance to the oxidation of LDL. Virgin olive oil has a higher content in very bioactive phenolic compounds (oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol), vitamin E and other antioxidants which “conventional” olive oil loses in the refining process. Olive oil resists frying temperatures well.

Beyond the measurement of intermediate markers of cardiovascular risk, there is little evidence from clinical studies on the effects of the consumption of different oils on the incidence of cardiovascular events. One epidemiological study found an association between an increased risk of myocardial infarction and the consumption of palm oil, compared to soybean oil.10 The positive effect of the Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra virgin olive oil on cardiovascular prevention has been demonstrated in the PREDIMED study, providing first level scientific evidence on its healthy effects.5 Also, in a meta-analysis of 32 cohort studies, when comparing the higher and lower tertiles of olive oil consumption, they found a reduction in the risk of total mortality, with a relative risk (RR) of 0.77 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.71–0.84, cardiovascular events (RR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.57–0.91) and cerebrovascular accident (RR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.47–0.77). It is worth noting, however, that the above benefit of olive oil is not observed when analysing the intake of monounsaturated fatty acids.11

Virgin olive oil is a fundamental component of the Mediterranean diet, giving a higher fat content to this food pattern and improving its palatability, being recommended as principal culinary fat both in cooking and at the table. Dishes prepared with tomato sauce, garlic, onion or leeks, made with virgin olive oil (Spanish sofrito), so characteristic of the Mediterranean diet, can be eaten daily.6

EggsEggs (fried in olive oil, scrambled, in Spanish omelettes or on salads) are part of the Mediterranean gastronomic culture. They are a food of great nutritional value for their content in minerals (selenium, phosphorus, iodine and zinc) and vitamins (A, D and B2, B12, pantothenic acid and niacin). The main components of eggs are: ovalbumin, a protein of high biological value which contains all the essential amino acids; choline, an essential nutrient involved in the formation of cell membranes; and highly bioactive carotenoids, such as lutein and its isomer zeaxanthin, which are important for retinal structure and function.

The fat in eggs (11% of the edible portion) is in the yolk and contains about 200–230mg of cholesterol per unit (350–385mg/100g). Most of the fatty acids in eggs are unsaturated (5g/100g of monounsaturates and 1.2g/100g of polyunsaturates), while they only contain 3g/100g of saturated fatty acids.

Due to their high cholesterol content, eggs have been associated with increased blood cholesterol levels and this is one of the reasons for egg intake being restricted in dietary recommendations for cardiovascular disease prevention. However, clinical studies have shown that increases in total cholesterol and LDL-C from eating eggs are minor, even more so in the context of low-saturated fat diets, although there is notable interindividual variability in response. It is estimated that only one third of individuals are hyper-responders and would experience an increase in both LDL and HDL fractions, but without modifying the atherogenic LDL/HDL cholesterol ratio. Moreover, consumption of eggs promotes the development of large, less atherogenic LDL particles.12

A large epidemiological population study assessed the relationship between egg consumption and the development of cardiovascular events and found no evidence to support egg intake being linked to the development of coronary heart disease. There was even evidence to suggest a 12% decrease in the risk of stroke with one egg per day.13

Therefore, there seems to be no reason to restrict egg intake based on the view of reducing cardiovascular risk. Based on the latest evidence, the Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis [Spanish Atherosclerosis Society] 2018 recommendations document on lifestyle in cardiovascular prevention allows daily consumption of whole eggs in any culinary preparation,6 although it limits intake to three a week in patients with diabetes (Table 2); in a meta-analysis of prospective studies, egg consumption was related to an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in American cohorts,14 but not in European cohorts,15 perhaps due to differences in dietary patterns and consumption habits between different populations. Americans tend to eat eggs accompanied by processed foods such as bacon, which are not very advisable from a cardiovascular health point of view, and this habit is perhaps less established in European populations. It was also recently found in an Asian cohort that more than four eggs per week in patients with diabetes increases cardiovascular risk.16

In conclusion, the evidence suggests that egg consumption is not detrimental to cardiovascular health in Spain and can be part of a healthy diet.

MeatMeats are protein-rich foods with high biological value (with the presence of essential amino acids). They contain fats, cholesterol, B vitamins and minerals, such as iron, potassium, phosphorus and zinc, which have high bioavailability and are absorbed better than from other sources of plant origin.

The fat content in different meats is variable, being lower in the so-called white meats (chicken, turkey and rabbit and certain cuts of pork) than in red meats and higher in beef or lamb than in pork. Within the same type of meat, quality is affected by genetic and animal feed factors, as well as processing. Red meats and processed meats contain a relatively high amount of saturated fatty acids.

The fat content also varies according to the anatomical part, being lower in pork loin than in rib or bacon. In lamb it is lower in leg meat than in chops and, in the case of the beef, the fat content in sirloin is a quarter of that in other parts of the animal, such as skirt or flank steak. It should be noted that there are two types of fat in meat: the intramuscular, infiltrated through and inseparable from the muscle forming part of lean meat; and the external or intermuscular fat, which can easily be separated. To lower our intake of saturated fat when eating meat, we should select lean cuts and remove external fat before cooking.

The latest evidence does not show a consistent association between unprocessed meat intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease or total and cardiovascular mortality.17–19 The effects of meat consumption on the risk of developing cardiovascular disease have been shown to vary depending on the degree of processing,20 i.e. whether the meat is fresh (unprocessed) or has been processed and preserved for long-term storage. In the case of processed meat (bacon, sausages, etc.) there is a significant association between consumption and the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and total mortality.17–19

Red and processed meat have similar saturated fat and cholesterol content, which would indicate that these differential effects on health are attributable to other components. One explanation is that sausages and processed meat products, even those with low fat content, are treated to improve their shelf life and flavour by salting or smoking, so they contain far more sodium (∼400% higher in processed meat), preservatives and additives of the nitrite, nitrate and nitrosamine type.8 Nitrates and their derivatives, such as peroxynitrite, promote endothelial dysfunction and can induce insulin resistance and contribute to the increased cardiovascular risk and diabetes associated with higher consumption of processed meats.21 Additionally, commercial cooking at high temperature, commonly used in the preparation of processed meats, can introduce heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which may increase the risk of both cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.22 Charring of meat by grilling at home can produce these amines or aromatic hydrocarbons, making it advisable to use other cooking methods which do not cause the meat to blacken and leave burnt bits.

In short, moderate consumption of meat (not exceeding 4 servings per week) does not seem to increase cardiovascular risk, although it is necessary to choose lean cuts and remove visible fat before cooking.6 Meat is an important source of animal protein and should be alternated with fish, consuming one of these options per day. It is better to eat more white meat than red meat.6 The consumption of cold meats (chorizo and other types of dried and cured sausage) and other processed meats (even those advertised as “low fat”) cannot be recommended and should only be occasional.6

Fish and shellfishFish and shellfish are the main dietary source of long-chain n-3 fatty acids, which are especially abundant in oily fish (sardines, anchovies, tuna, herring, mackerel, salmon, trout, etc.) compared to white fish (cod, hake, monkfish, sole, John Dory, etc.). Feed in fish farms can affect the content in n-3 fatty acids in fish flesh, as can the seasons, with wild fish having a lower fat content in winter. Fish also contain other nutrients (peptides, selenium, iodine, vitamin D and choline), which may contribute to the benefits of fish consumption on cardiovascular health. Shellfish also contains marine sterols, which interfere with the intestinal absorption of cholesterol.

A meta-analysis showed that an increase of two servings/week of any type of fish is associated with a reduction in the risk of stroke from any cause, with a greater reduction found in the risk of ischaemic stroke.23 Other data show the cardiovascular protective effect of fish consumption, which seems to be associated with a reduction in sudden death. An association has been found between n-3 fatty acids and a lower heart rate and slower atrioventricular conduction, resulting in an anti-arrhythmic effect. The 2018 recommendations of the American Heart Association24 emphasise the importance of consuming fish and state that there seems to be a threshold effect with an approximately 50% reduction in the risk of sudden cardiac death with one or two servings of oily fish per week versus no fish consumption. An analysis of eight prospective studies shows a 5% decrease in the risk of acute myocardial infarction for each additional weekly consumption of a 100g serving of fish25 and corroborates the importance of eating fish in the prevention of coronary heart disease.

From a health point of view, another aspect to be considered is the presence in some fish of mercury contaminants, dioxins or polychlorinated biphenyls, which are incorporated into the marine food chain in such a way that their concentration is higher in larger fish and in predators. Mercury derivatives are toxicants and can affect foetal development, which is why pregnant women are advised to eliminate mackerel, swordfish and shark from their diets to minimise exposure.26 However, in general, the benefits of fish consumption seem to more than outweigh the potential risk of contaminants.6

In conclusion, for the general population the consumption of fish needs to be encouraged as one component of lifestyle modifications for cardiovascular disease prevention. Eating fish or shellfish at least three times a week is recommended, with two of these portions in the form of oily fish. Processed fish preparations are not advisable, as they can contain trans fatty acids and other additives.6

Dairy productsDairy products can be the food matrix paradigm as modulator of the effects of the fatty acids they contain. This is because, regardless of their content in saturated fat (in the case of whole milk products), they also contain other nutrients that can exert a protective role on cardiovascular health.8 Dairy products contain vasoactive peptides with an antihypertensive effect which inhibit angiotensin converting enzyme and odd chain saturated fatty acids such as pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) and heptadecanoic acid (C17:0). In prospective studies, the highest plasma concentrations of these fatty acids, a biomarker of dairy product consumption, are associated with a reduction in the risk of coronary heart disease and diabetes.27 Dairy products also provide proteins, carbohydrates, phosphorus and potassium, and are the most important dietary source of calcium and vitamin D.

Dairy product consumption has little influence on blood cholesterol levels. However, it has been associated with a lower risk of hypertension and one meta-analysis including 31 cohort studies even suggested a reduction in cardiovascular risk and showed an inverse association between the consumption of low-fat dairy products and the risk of coronary heart disease, while the effect of whole milk products was neutral.28 There is also an inverse association between the total intake of dairy products and the risk of stroke, especially with the intake of low-fat dairy products.29

Moreover, consumption of cheese did not produce the harmful effects on lipid profile expected because of its high content in saturated fat. Based on the results of two meta-analyses of epidemiological studies,28,30 there is solid evidence to suggest that cheese intake is not associated with increased cardiovascular risk. One meta-analysis31 even found a U-curve between the consumption of cheese and cardiovascular risk, such that the greatest risk reduction was observed for a cheese intake of around 40g/day. Due to their high sodium content, consumption of cured cheeses should be limited in hypertensive patients.

In short, the results of prospective cohort studies do not support milk and dairy products having a harmful effect on the risk of cardiovascular disease and suggest that restriction of these foods is not an appropriate strategy for cardiovascular protection. However, consumption of dairy products with added sugars is not recommended.

In view of their important nutritional role in the metabolism of calcium and their content in high biological quality proteins, the recommendations are to consume at least two servings of dairy products a day (one serving is 200ml of milk, one 125g yoghourt or 40g of cheese). For cardiovascular disease prevention, it is advisable to reduce consumption of concentrated milk fat, such as butter and cream, and replace it as cooking fat with other sources of unsaturated fats,8 such as olive oil.

GrainsGrains are foods rich in carbohydrates, with the most consumed in our diet being wheat, rice and maize. They contain few fats and their proteins are of lower biological value than those in meat or eggs as they are deficient in some amino acids (usually lysine or tryptophan, in the case of maize). Wholegrains are those which contain the whole grain. In the process of grinding to obtain refined grains, the seed and the peel are removed, with the loss of substances such as B vitamins, minerals (potassium, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, iron, zinc and silicon) and other antioxidants, which are therefore present in lower quantities in refined cereals than in wholegrains.

Higher consumption of wholegrains has been associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease.32 This benefit seems to be due to the antioxidant phytochemical compounds they contain and their content in dietary fibre, which is mostly insoluble in water in wheat and corn, but soluble in oats and barley. Insoluble fibre regulates intestinal transit and helps fight constipation, while soluble fibre slows intestinal absorption and modulates postprandial hyperglycaemic peaks. Consumption of wholegrains, especially oats and barley rich in β-glucans, which are a type of soluble fibre, interferes with the intestinal solubilisation of cholesterol, reducing its absorption. It also contributes to a modest reduction in cholesterol levels associated with a slight increase in plasma concentrations of HDL-C. Diets high in complex carbohydrates (pulses, wholegrains) have a low glycaemic index or load and reduce postprandial blood glucose and insulin. In contrast, diets high in refined cereals can increase blood triglyceride levels, reduce HDL-C, increase the remaining lipoproteins high in triglycerides, produce a pattern of small and dense LDL and increase blood glucose, effects associated with an increased cardiovascular risk.

Dietary recommendations need to be directed at increasing the consumption of wholegrains as opposed to refined cereals (wholegrain bread and cereals instead of white bread and refined cereals). The recommended intake of wholegrains is about four servings/day, including bread at all mealtimes, pasta two to three times/week and rice two to three times/week.6

PulsesPulses are foods high in complex carbohydrates, such as starch. They also contain 5–9% protein and B vitamins, folic acid, calcium, potassium, non-haem iron, bioactive phytochemicals such as phytosterols and saponins, and potent antioxidants of the polyphenol type. Pulses are deficient in methionine, an essential amino acid. Therefore, to achieve a good quality protein intake in the diet, methionine needs to be supplied by other foods. A good combination are pulses (chickpeas, lentils or beans) with rice or potatoes, which do provide methionine even though they are lacking in other amino acids, such as lysine, as these are supplied by the pulses.6 Pulses are an important source of soluble fibre which, like that present in oats and barley, interferes with the solubilisation of cholesterol in the intestine, modestly reducing blood cholesterol levels. They contain phytosterols which, due to structural similarity, compete with cholesterol of dietary or biliary origin, reduce its intestinal absorption and increase its elimination in the faeces. This results in an additive cholesterol-lowering effect on top of that of soluble fibre.

A meta-analysis found the consumption of 100g of pulses (4 times/week) to be associated with a 14% decrease in the risk of coronary heart disease.33 Another more recent meta-analysis of prospective studies of 11 cohorts including 367,000 individuals concluded that consumption of pulses is associated with a lower risk of total cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease.34 As with wholegrains, pulses have a low glycaemic index and a lower postprandial hyperglycaemia capacity. Therefore, they are recommended in patients with diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome, although there is no clear evidence that they reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Consumption of pulses has, however, been associated with lower body weight and waist circumference, possibly due to the satiating effect produced by the fibre content.

In short, we can conclude that to promote cardiovascular health, a serving of pulses is advisable at least four times a week.6

NutsThe nuts most consumed here in Spain are almonds, hazelnuts and walnuts. Brazil nuts, pecans, pine nuts, macadamia nuts, cashews and pistachios are also popular. Although they are legumes, peanuts share similar nutritional characteristics.

Nuts are foods with a high calorific value. In terms of nutritional composition, more than 50% of their weight is fat, with a higher content in monounsaturated fat (oleic in hazelnuts and almonds) and n-3 polyunsaturated fat (alpha linolenic in walnuts) and little saturated fat. The cardioprotective properties of nuts have been attributed not only to their peculiar fat composition, but also to the presence of fibre, vitamins (folic acid, vitamin E, vitamin B6), minerals (calcium, magnesium, potassium, zinc) and other bioactive components, such as antioxidants and phytosterols, etc.35 They also contain appreciable amounts of important amino acids such as arginine, which is a precursor of nitric oxide or endogenous vasodilator and could explain why a diet enriched with walnuts improves endothelial dysfunction associated with hypercholesterolaemia, beyond the reduction of cholesterol.36 Epidemiological evidence collected in a meta-analysis shows that the regular consumption of nuts reduces the risk of coronary heart disease, total cardiovascular disease and both cardiovascular and all-cause death.37 In the PREDIMED study, the group randomised to the Mediterranean diet supplemented with nuts (30g/day) showed a significant reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rates compared to the low-fat control diet.4

The majority of randomised clinical studies which compared the daily intake of nuts in the context of a healthy diet to equivalent diets without nuts demonstrated a reduction in cholesterol levels. The decrease in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol ranges from 5% to 15% with daily doses of 30–75g of nuts, with the cholesterol-lowering effect being greater the higher the cholesterol at the beginning of the intervention.6,38 Despite the high energy content in nuts, in medium-term studies, healthy people provided with daily supplements of nuts did not gain weight. This has been attributed in part to the satiating effect caused by eating nuts, which leads to a lower intake of other high-energy foods and, to a lesser extent, to malabsorption of the fat contained in the nuts; it is less bioavailable than other fats because it is enclosed within cell membranes, especially if the nuts are not chewed well.35

In short, nuts can be recommended for regular consumption in all risk groups: people with hypercholesterolaemia or hypertension, obesity and/or type 2 diabetes.35 Consumption daily or at least three times a week of a handful (equivalent to about 30g) of raw nuts (not salted or toasted) is recommended; and preferably unpeeled, as most of the antioxidants are in the skin. To maintain the satiating effect and avoid weight gain, nuts are better eaten during the day, not to finish off a main meal.6

Cocoa and chocolateCocoa is the fruit of the cacao tree (Theobroma cacao) and is what chocolate is made from. Cocoa is high in fat, and contains minerals such as potassium and magnesium, as well as other substances which may contribute to its beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system such as arginine, theobromine and tryptophan. Its high content in a type of flavonoids, flavanols (which include catechin and epicatechin) seem to exert vascular protective effects.39

Dark chocolate is made from chocolate paste and cocoa butter (fat fraction of cacao), is rich in polyphenols of the flavonoid class and has a higher proportion of cacao and less dairy products and sugar than other types of chocolate. It is composed 45–60% of carbohydrates and 30–40% of mostly saturated fat, mainly stearic acid, which does not have a cholesterol raising effect as it is desaturated in the body to oleic acid, the effects of which on plasma cholesterol are different from those produced by other saturated fatty acids (palmitic, myristic and lauric). White chocolate lacks the content in antioxidants as it is made exclusively from cocoa butter and milk, without cocoa paste. Milk chocolate, however, has a minimum of 25% of total dry cocoa solids and powdered or condensed milk is added to that.

The results of 14 prospective studies collected in a meta-analysis have linked higher consumption of chocolate with a lower incidence of coronary heart disease, stroke and even type 2 diabetes, concluding in a dose–response analysis that the maximum benefit is obtained by consuming 2–3 servings of 30g/week.40 Another recent meta-analysis which included 23 studies with over 400,000 participants corroborates the cardiovascular benefit of chocolate consumption of <100g/week.41 Other studies suggest the protective effect of cocoa consumption on cardiovascular health mediated by its antihypertensive and antiplatelet effects, and the fact that it increases HDL-C and improves endothelial function, blood glucose control and insulin resistance. These effects, analysed in a recent review,42 have been demonstrated both in healthy subjects and in patients with risk factors (hypertension, diabetes and smoking) or with a history of cardiovascular disease. The underlying mechanism involved in this benefit seems to be modulated by the content in cocoa flavonoids, which promote nitric oxide synthesis. The anti-inflammatory effects inherent in eating chocolate high in polyphenols are attributable to its ability to inhibit 5-lipoxygenase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of leukotrienes.43 Another meta-analysis confirms the anti-inflammatory and vasculoprotective effects of cocoa.44

Many cocoa derivatives on the market have added simple sugars and other fats, and are not recommended. In the context of a healthy diet, dark chocolate with cocoa ≥70% can be eaten daily, although it is advisable to have it during the day, not at night after the evening meal, when the satiating effect cannot be compensated by eating less food at the next meal.6

Coffee and teaCoffee and tea are beverages rich in polyphenols with antioxidant capacity. One meta-analysis found a greater reduction in cardiovascular risk (15%) for a consumption of three to five cups/day of coffee, with a similar benefit for coronary heart disease and stroke.45 Coffee consumption, including decaffeinated, has also been associated with a reduction in the risk of type 2 diabetes and a lower risk of cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.46 A recent prospective study corroborates the inverse relationship between coffee consumption, with or without caffeine, and total mortality.47 A polyphenol present in coffee, chlorogenic acid, antagonises glucose transport, attenuating its intestinal absorption and modulating postprandial hyperglycaemia, with the effect of improving insulin resistance.35 Although acutely, caffeine consumption increases blood pressure, when ingested through coffee, the effect is small and transient, to the extent that in a recent meta-analysis, coffee consumption was even inversely associated with the risk of hypertension.48 The effect on serum lipid levels varies according to the method of preparation and the type of coffee: filtering or instant does not increase cholesterol levels, while unfiltered coffee contains diterpenes, which can increase blood cholesterol.49

Another meta-analysis showed regular consumption of green or black tea to be associated with a decrease in cardiovascular risk (both coronary heart disease and stroke) and total mortality.50 There is also evidence that daily tea consumption moderately reduces blood pressure and total cholesterol and LDL-C.51 The beneficial effects seem to be mediated by tea's high content in flavonoids, which exert an antiatherogenic effect (inhibition of LDL oxidation and improvement of endothelial function).35

In short, regular consumption of up to five cups of coffee (filtered or instant, normal or decaffeinated) or tea (black or green) a day is beneficial for cardiovascular health.6

Vegetables, fruits and tubersVegetables and fruits are low-fat foods, rich in antioxidants, vitamins and fibre. However, there are fruits such as coconut, which is rich in saturated fat, and avocado, which has a high proportion of monounsaturated fat. Due to their high-water content (70–90%), vegetables and fruits are low energy density foods which are low in calories. The carbohydrate content is higher in fruits than in vegetables.

The traditional Mediterranean diet is characterised by the consumption of a wide variety of fruits and vegetables, in different culinary preparations, both raw and in salads, gazpachos or in different stews in which the “sofrito” is used (tomato sauce, garlic, onion or leeks prepared at low heat with virgin olive oil) as a substantive basis. The different ways of processing food can modify the bioavailability of its components. In the case of sofrito or gazpacho, tomato lycopene improves its bioavailability and is better absorbed than that present in raw tomatoes. However, other cooking techniques such as scalding, boiling, baking and the use of microwaves can reduce the concentration of antioxidants by up to 50%.22 To prolong the preservation of fruits such as plums, grapes (raisins), figs, dates, etc., they undergo drying processes to dehydrate them. This increases their calorie and sugar content, but also the content in fibre, and they still maintain the beneficial effect of the antioxidants they contain, especially polyphenols. There is evidence that consumption of dried fruits improves the nutritional quality of the diet and is inversely associated with weight gain.52 In the case of freshly squeezed fruit juices, it should be noted that, even though they retain most of the antioxidants, they lose the essential supply of fibre, which remains in the pulp left behind in the juicer.

A diet with a high content of fruits and vegetables is rich in nutrients and other beneficial bioactive components, including soluble and insoluble fibre, sterols, carotenoids (lycopene, lutein, β-carotene, etc.), vitamin C, flavonoids, folates, magnesium and potassium. The complex mixture of these components may be responsible for their antioxidant and antiatherogenic activity and mediate their cardiovascular benefit. A diet with a varied consumption of fruit and vegetables gives a greater richness of antioxidants, which can act synergistically.

A DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, rich in vegetables and fruits, limiting the consumption of salt, is one of the proposed strategies for the control of hypertension.53 The available epidemiological evidence indicates that people who consume more fruit and vegetables have a lower prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (both cerebrovascular and coronary heart disease),54 although their reducing effect on blood pressure provides greater protection against stroke than against coronary heart disease.

A diet rich in fruit and vegetables should be the basis of a healthy diet, both in the general population and in people with higher cardiovascular risk. A recent meta-analysis of observational studies supports recommendations to increase fruit and vegetable intake in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer.54 In the context of our Mediterranean diet the recommendation is that, between vegetables and fruit, we consume at least five portions a day.6

Tubers (potatoes, sweet potatoes, sweet potato, cassava and beet) are rich in carbohydrates, specifically starch (18%), contain very little fat (0.2%) and provide various minerals, such as potassium, iron, phosphorus, calcium, magnesium and zinc. A study in the United States has shown an association between the intake of four or more servings of potatoes per week (boiled or baked) and the development of hypertension, greater with the consumption of chips.55 However, it should be taken into account that the three large cohorts analysed were from the United States, where potatoes tend to be accompanied by unhealthy fats; the same association was not found in the follow-up of Spanish cohorts.56 That finding may be explained by the fact that in Spain potatoes are usually consumed along with vegetables and olive oil. A meta-analysis of observational studies did not find any association between potato consumption and cardiovascular risk, but there is an increased risk of type 2 diabetes with high consumption of chips.57

Moderate consumption of 2–4 servings a week of tubers is recommended, preferably roasted or boiled. Commercially processed potatoes with added salt should be limited to occasional consumption.6

Alcoholic beveragesAlcoholic beverages are drinks that contain ethanol, with a distinction between those made by distillation (whiskey, cognac, gin, vodka, rum, etc.), which have a high alcohol content (usually from 30° to 50°); or by fermentation (wine, beer, cava, mead and cider), whose alcohol content does not usually exceed 15°. Moderate consumption of alcoholic beverages is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular mortality rates, both when compared to abstainers and heavy drinkers.58,59 This U-curved relationship shows the greatest benefit with a consumption of about 20g of ethanol per day in men and 10g in women.

The cardioprotective effect produced by the moderate consumption of alcoholic beverages has been attributed to a significant increase in HDL-C and a reduction in fibrinogen. It has also been found that, at equivalent amounts of alcohol, fermented beverages seem to exert a greater protective effect, probably due to their content in polyphenols with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which may affect the atherosclerosis process.

It is never recommended to encourage the consumption of alcohol, but there is no reason to prohibit it to adults who are already used to consuming low-proof fermented beverages in moderation. Doctors should not promote the consumption of alcoholic beverages as an instrument for cardiovascular prevention or encourage consumption in abstainers. Alcohol can increase serum triglycerides, with this effect being more significant in patients with hypertriglyceridaemia, so the recommendation for them is to abstain from alcohol. Nor is it advisable for pregnant women, people who work with machinery or who are going to drive, or those who have a history of disorders that contraindicate alcohol (liver disease, history of addictions, etc.) to consume alcohol, even in small quantities. The risk of all-cause mortality and specifically cancer mortality increases with levels of consumption.60

The profile of daily consumption of fermented alcoholic beverages in small or moderate amounts with meals in the framework of a healthy Mediterranean-type diet is the most recommended. Under no circumstances can occasional binge drinking (weekends) be recommended, as this has been linked to an increase in accidents and a higher incidence of pancreatitis.

The recommendations for men and women are different, as women are more sensitive to the effects of alcohol. The accepted consumption for men would be two or three drinks of a fermented beverage (maximum: 30g of alcohol per day) and for women, one or two drinks (maximum: 15g per day). Men over the age of 65 should also not drink more than 20g of alcohol per day.6 In any event, the safe limit of alcohol consumption remains open to debate, but is in the range 20–30g/day for men and 10–15g/day for women. In young people, cardiovascular risk is very low but alcohol intake increases the risk of mortality, as the possible cardiovascular protection is counteracted by the increased risk of accidents.

Sugary drinksThe impact of the consumption of this type of beverage on cardiovascular health has been assessed in numerous epidemiological studies, most of which conclude that frequent consumption alters sensitivity to insulin and contributes to the development of obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. There is also evidence of a relationship with hypertension, particularly when the sweetener is fructose.61,62 A meta-analysis of seven prospective cohort studies with more than 300,000 participants indicates an increased risk of stroke and myocardial infarction as the consumption of sugary drinks increases.63 Substituting sugary drinks for water would be an important step towards reducing calorie intake and the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes and related diseases.6

SaltThere is epidemiological evidence of a direct association between excess salt (sodium) intake and the development of hypertension, kidney disease, and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.64 A modest reduction in salt intake for four or more weeks can help reduce blood pressure, without modifying lipid concentrations.65 There is an increased risk of all-cause mortality associated with high salt intake, with a direct linear relationship occurring even at low levels of sodium.66 Excessive sodium consumption is shown in one epidemiological study to be the first of ten nutritional factors responsible for death from cardiometabolic diseases.67

In order to reduce dietary sodium, we should be careful about the amount of salt added to food, restricting pre-cooked, canned and salted foods, dried and cured meats and carbonated beverages, which are all typically high in sodium. We need to be aware that during processing, many foods can have preservatives added which are high in sodium (sodium citrate, sodium propionate, sodium nitrate, sodium glutamate, sodium ascorbate, etc.) in order to improve flavour and help preserve them. Other products with a high sodium content include bakery products, ice cream, bread and biscuits. When cooking foods, to improve their palatability, there are many condiments that can be used instead of salt, such as spices, lemon juice, aromatic herbs or garlic.

For the general population and especially in hypertensive patients, a low salt diet is recommended (NaCl <5g/day), remembering that in order to calculate the total amount of salt, the number of grams of sodium has to be multiplied by 2.5.6 In diabetic patients, half that is even recommended as the daily limit.

How to implement a nutritional strategy in our patients in primary careNumerous studies show that lifestyle changes are effective in reducing the burden of disease and improving people's health. Through PC consultations, we need to be participative in the approach to, treatment and follow-up of patients with disorders where nutritional intervention is key, both from an individual and group perspective. To achieve this, collaboration and coordination with nursing staff is a determining factor68 and will help us apply uniform criteria to the recommendations to be transmitted.

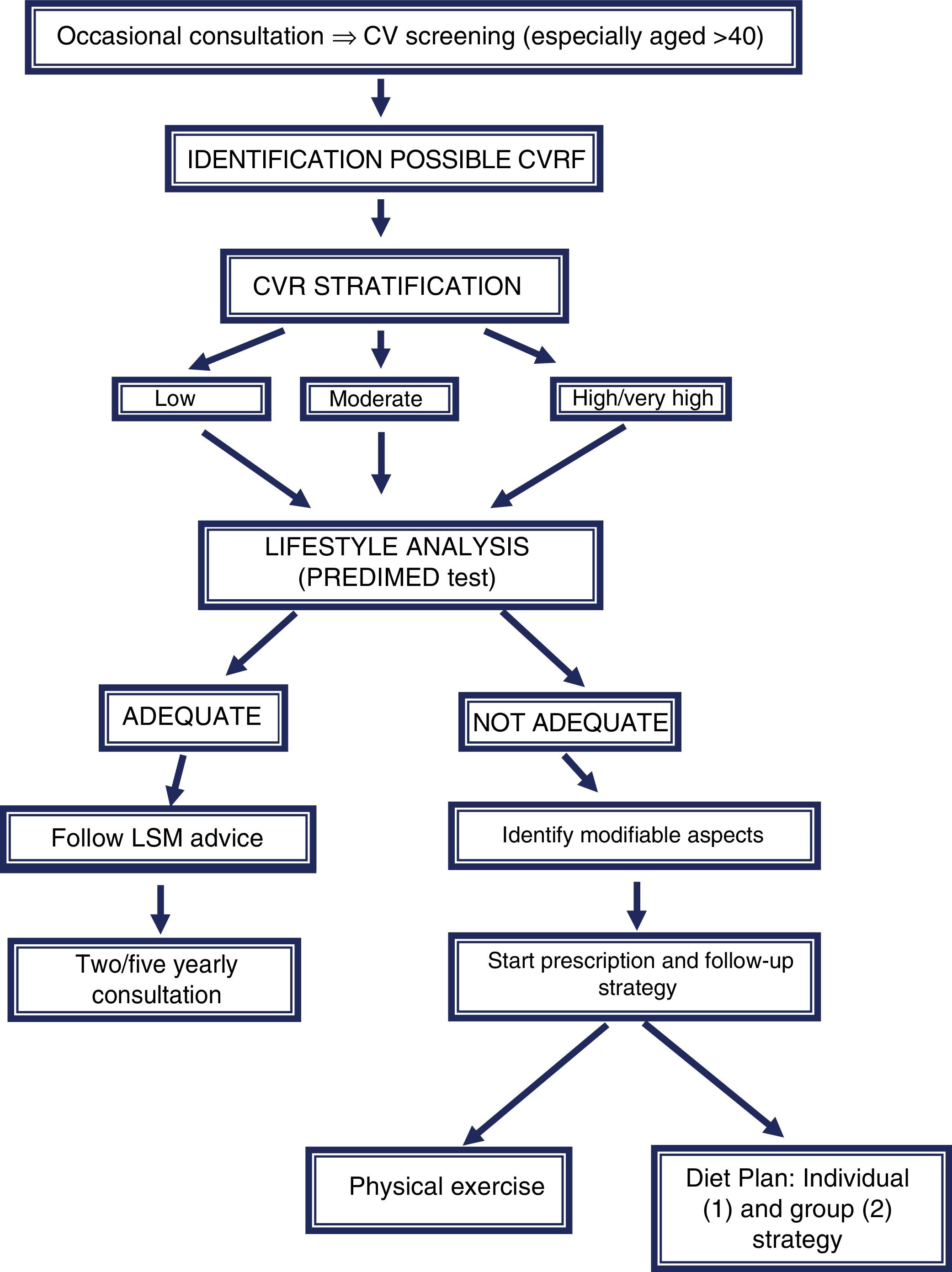

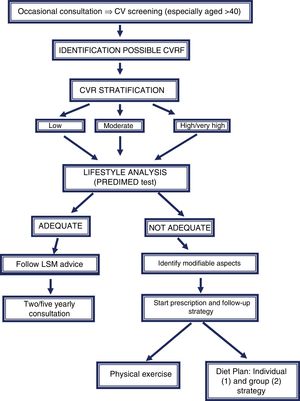

Dietary advice, or rather the dietary prescription, needs to be implemented as soon as possible, taking advantage of any opportunity in which a patient attends the clinic. There are very limited data on the efficacy of dietary advice at a population level, and the few available results are not very encouraging.69–72 In this consensus a strategy of lifestyle analysis and diet prescription is proposed, to be implemented jointly with nursing staff (Fig. 1).

Lifestyle modification (LSM) prescription algorithm in primary care consultations for patients with cardiovascular (CV) screening. (1) Individual strategy: initial consultation and back-up consultations (1–3–6–12 months). (2) Group strategy: group sessions, 4 sessions (2–4–8–10 months).

After stratification of the patient's cardiovascular risk, conducting the PREDIMED study survey (Table 1) will allow us to identify aspects to improve among their dietary habits. The aim is to agree on a general plan with the patient, with practical recommendations adapted to their personal characteristics, establishing realistic objectives, and not delay introduction of the necessary changes, with a good strategy being to place more emphasis on recommending the use of certain foods and cooking techniques rather than on prohibiting others. Successive future contacts will facilitate adherence to the proposed lifestyle modification plan. Feedback is also essential for the patient, so they can see how the lifestyle changes have improved anthropometric (weight, waist circumference) or biochemical parameters (blood glucose, lipid profile, etc.), blood pressure and quality of life in general.

ConclusionsThe current paradigm in nutrition science states that the basic nutritional unit is not nutrients, but the foods that contain such nutrients (oils, nuts, dairy products, eggs, red or processed meats, etc.), which act as a food matrix in which different nutrients synergistically or antagonistically modulate their effects on the different metabolic pathways which are determinants of health and disease. Food is not based on isolated nutrients or foods but on complex mixtures of ingredients which are part of a specific food pattern, and this concept has been singled out as the most relevant for analysing the associations between nutrition and health or disease.6

In our region, the dietary pattern model to be preserved is the Mediterranean diet, characterised by the fact that the main cooking fat is olive oil and that it includes large amounts of vegetables, fruit, pulses and nuts, fish, poultry, fermented dairy products (yoghurt and cheese) and wine (with meals) in moderation, and only small quantities of meat and meat products, processed foods in general, sweets and sugary drinks.

This document summarises the available evidence on the association between different foods and cardiovascular health, and offers simple recommendations to be introduced into the dietary advice provided by healthcare professionals.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pascual V, Perez Martinez P, Fernández JM, Solá R, Pallarés V, Romero Secín A, et al. Documento de consenso SEA/SEMERGEN 2019. Recomendaciones dietéticas en la prevención cardiovascular. Clín Investig Arterioscler. 2019;31:186–201.