We present the Spanish adaptation of the 2021 European Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) prevention in clinical practice. The current guidelines besides the individual approach greatly emphasize on the importance of population level approaches to the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Systematic global CVD risk assessment is recommended in individuals with any major vascular risk factor. Regarding LDL-Cholesterol, blood pressure, and glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus, goals and targets remain as recommended in previous guidelines. However, it is proposed a new, stepwise approach (Step 1 and 2) to treatment intensification as a tool to help physicians and patients pursue these targets in a way that fits patient profile. After Step 1, considering proceeding to the intensified goals of Step 2 is mandatory, and this intensification will be based on 10-year CVD risk, lifetime CVD risk and treatment benefit, comorbidities and patient preferences.

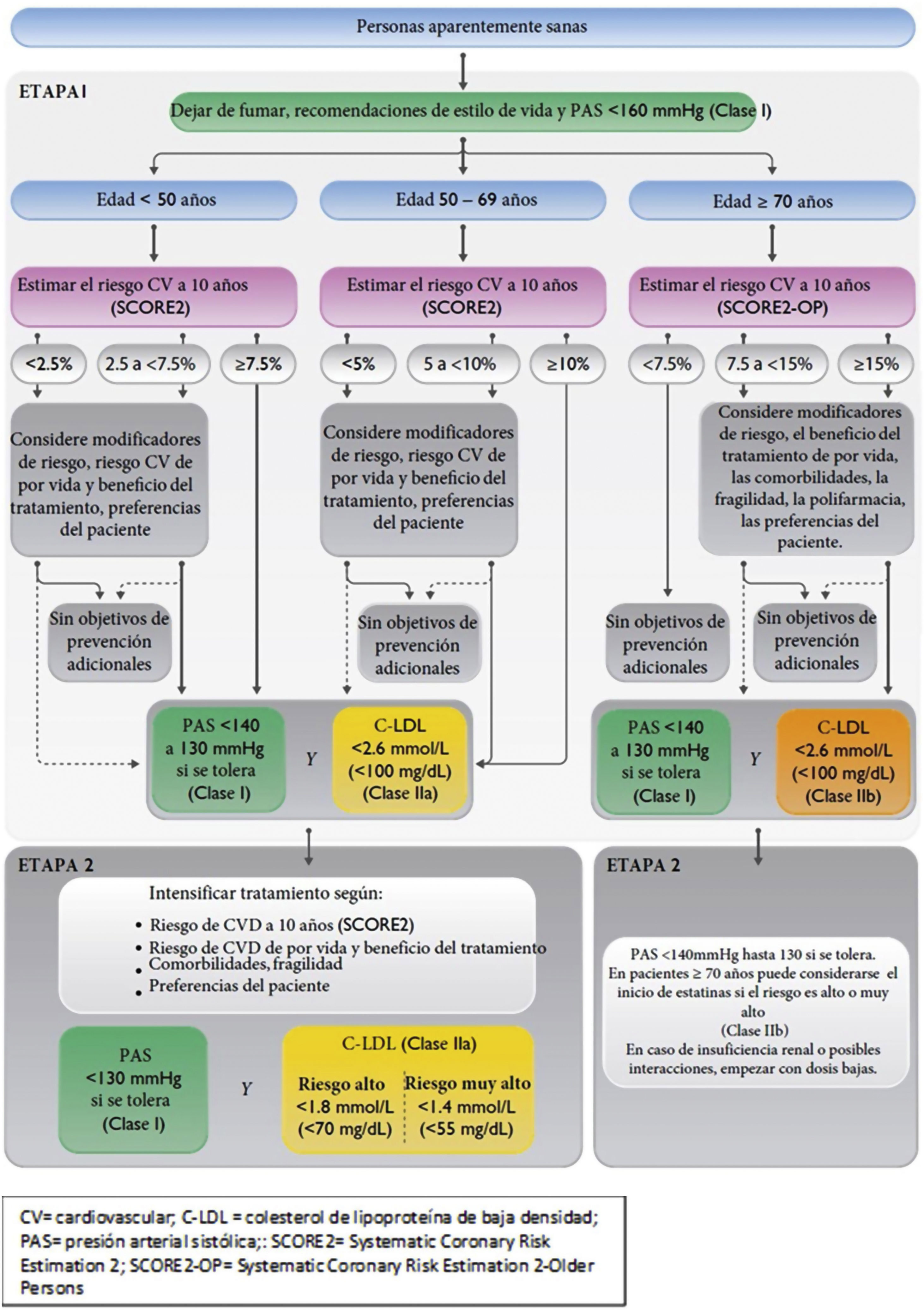

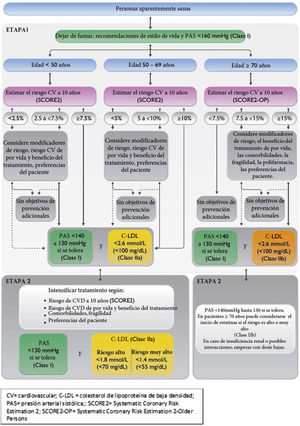

The updated SCORE algorithm—SCORE2, SCORE-OP— is recommended in these guidelines, which estimates an individual’s 10-year risk of fatal and non-fatal CVD events (myocardial infarction, stroke) in healthy men and women aged 40–89 years. Another new and important recommendation is the use of different categories of risk according different age groups (<50, 50−69, ≥70 years).

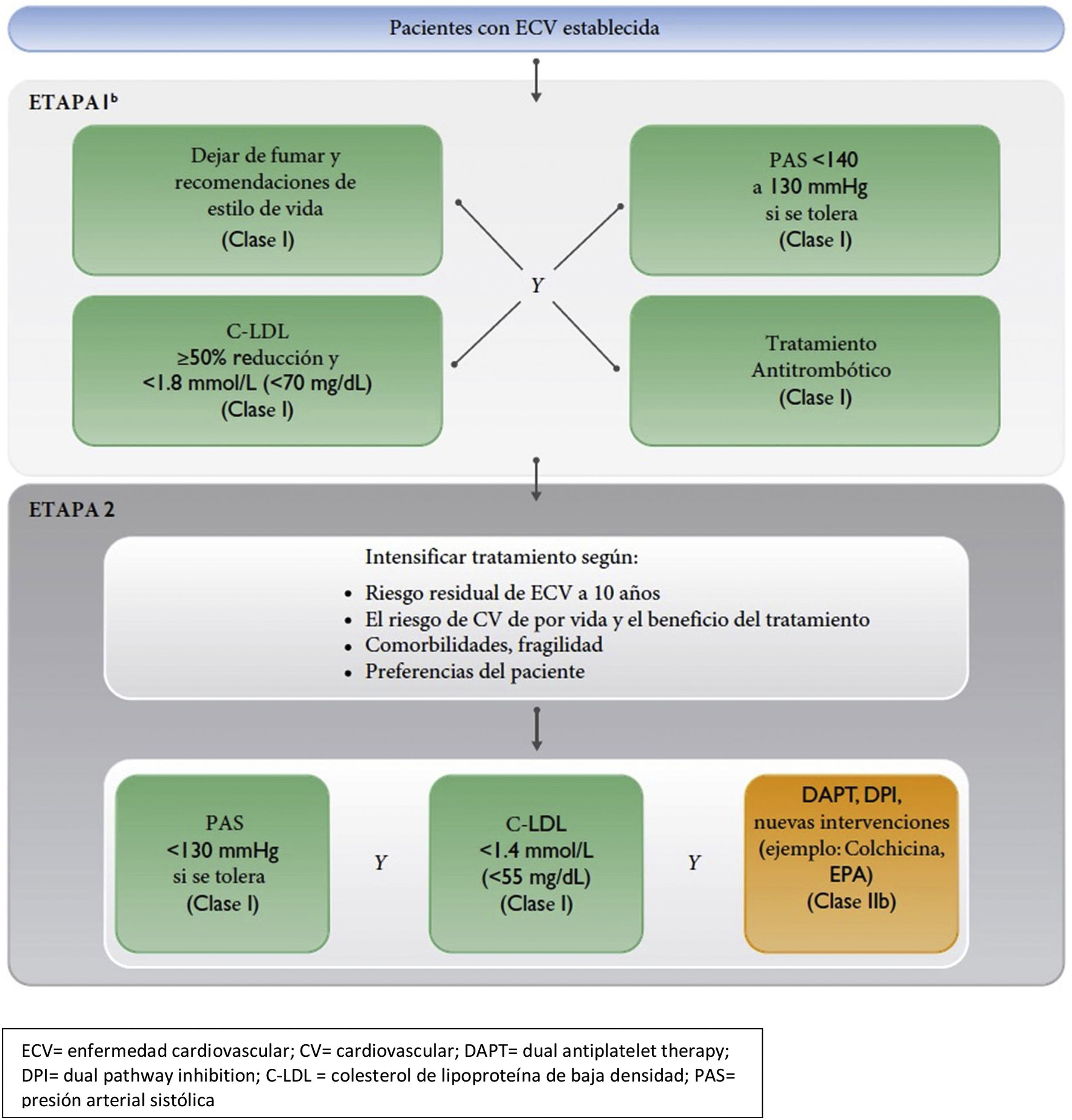

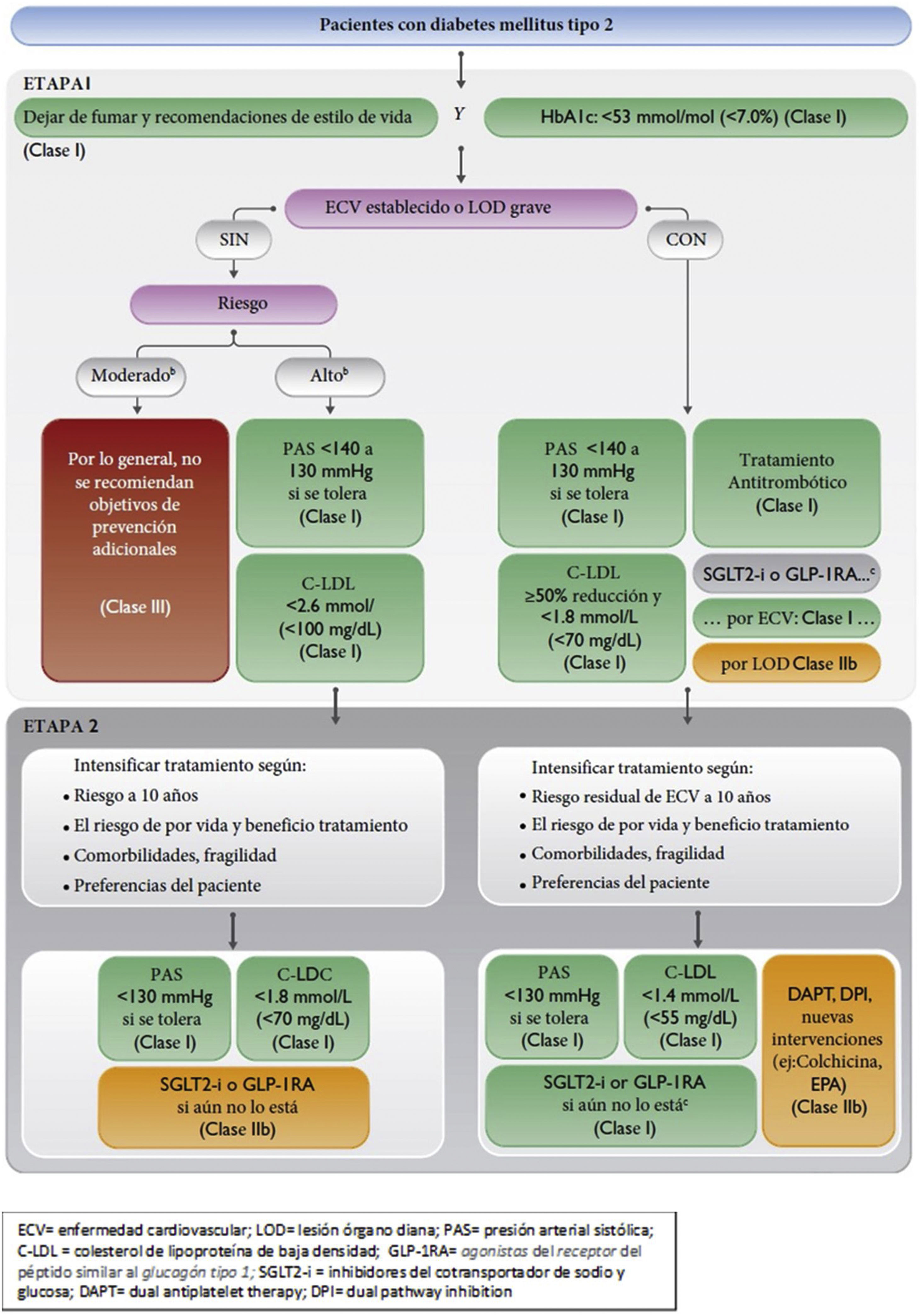

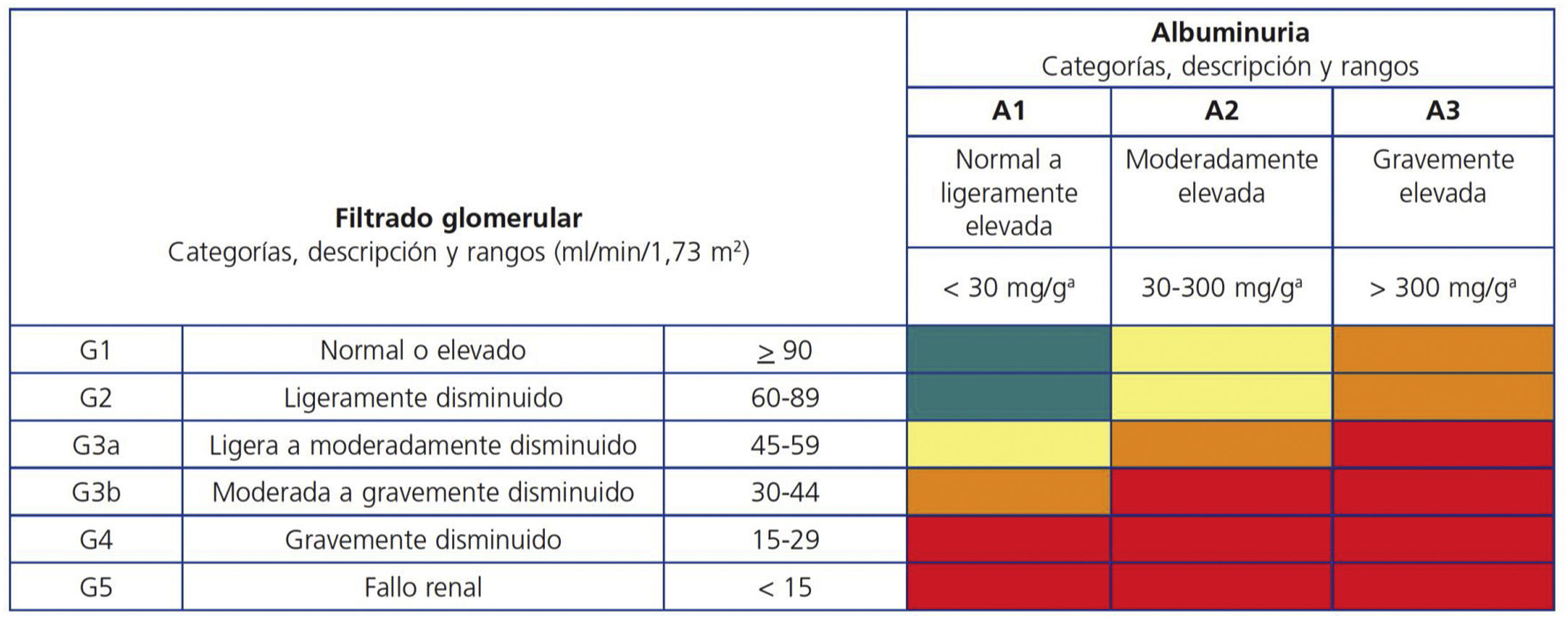

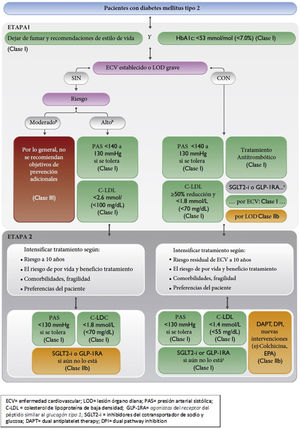

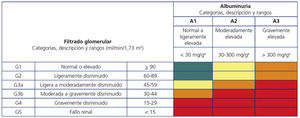

Different flow charts of CVD risk and risk factor treatment in apparently healthy persons, in patients with established atherosclerotic CVD, and in diabetic patients are recommended. Patients with chronic kidney disease are considered high risk or very high-risk patients according to the levels of glomerular filtration rate and albumin-to-creatinine ratio. New lifestyle recommendations adapted to the ones published by the Spanish Ministry of Health as well as recommendations focused on the management of lipids, blood pressure, diabetes and chronic renal failure are included.

Presentamos la adaptación española de las Guías Europeas de Prevención Cardiovascular 2021. En esta actualización además del abordaje individual, se pone mucho más énfasis en las políticas sanitarias como estrategia de prevención poblacional. Se recomienda el cálculo del riesgo vascular de manera sistemática a todas las personas adultas con algún factor de riesgo vascular. Los objetivos terapéuticos para el colesterol LDL, la presión arterial y la glucemia no han cambiado respecto a las anteriores guías, pero se recomienda alcanzar estos objetivos de forma escalonada (etapas 1 y 2). Se recomienda llegar siempre hasta la etapa 2, y la intensificación del tratamiento dependerá del riesgo a los 10 años y de por vida, del beneficio del tratamiento, de las comorbilidades, de la fragilidad y de las preferencias de los pacientes. Las guías presentan por primera vez un nuevo modelo para calcular el riesgo -SCORE2 y SCORE2-OP de morbimortalidad vascular en los próximos 10 años (infarto de miocardio, ictus y mortalidad vascular) en hombres y mujeres entre 40 y 89 años. Otra de las novedades sustanciales es el establecimiento de diferentes umbrales de riesgo dependiendo de la edad (<50, 50−69, ≥70 años).

Se presentan diferentes algoritmos de cálculo del riesgo vascular y tratamiento de los factores de riesgo vascular para personas aparentemente sanas, pacientes con diabetes y pacientes con enfermedad vascular aterosclerótica. Los pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica se considerarán de riesgo alto o muy alto según la tasa del filtrado glomerular y el cociente albúmina/creatinina. Se incluyen innovaciones en las recomendaciones sobre los estilos de vida, adaptadas a las recomendaciones del Ministerio de Sanidad, así como aspectos novedosos relacionados con el control de los lípidos, la presión arterial, la diabetes y la insuficiencia renal crónica.

The new European Guidelines for Cardiovascular Prevention1 were published 5 years after the last guidelines of 2016,2 although an update was made in 2020,3 on which the Spanish Interdisciplinary Vascular Prevention Committee (CEIPV) made a critical commentary.4

The 2021 guidelines were developed by 13 European scientific societies and have introduced significant new features, which are discussed below. In addition to the individual approach to cardiovascular prevention, they place special emphasis on the population and public health strategy, which the CEIPV has always considered highly relevant, as reflected in the documents published and the programmes of the biennial conferences organised by the Ministry of Health. These are more complex than previous guidelines because they seek a more personalised approach, which certainly reflects the phenotypic diversity of the patients seen in clinical practice.

Vascular risk assessmentThe new guidelines on cardiovascular prevention recommend systematically calculating vascular risk (VR) in all adults with any VR factor, which could also be in men>40 years and women>50 years, and repeated every 5 years. Some publications5 have highlighted potential risks of labelling people as low VR, as they may be given a false sense of security that they are protected from vascular disease, which might compromise their motivation to prevent risk factors. Most of the population fall into these risk bands (moderate or low), where more cases of vascular disease occur in absolute numbers. Therefore, it is essential to promote health lifestyles in the entire population.

The therapeutic targets for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), blood pressure (BP), and blood glucose have not changed from the previous guidelines, but the way they are controlled in individuals has been modified in a stepwise manner (steps 1 and 2). This approach is not new as a concept, and is intended to reflect the usual clinical practice of the progressive intensification of therapeutic strategies as part of a shared decision-making process between healthcare professionals and patients. It is always recommended to get to step 2, and treatment will be intensified according to 10-year and lifetime risk, treatment benefit, comorbidities, frailty, and patient preferences. However, we should not forget that according to the results of the EUROASPIRE study,6 conducted in 27 European countries, we are still a long way from achieving therapeutic objectives (71% of people with coronary heart disease had LDL-C≥70 mg/dl), and this stepwise strategy could encourage inertia, compromising the earliest possible achievement of objectives, especially in patients with high or very high CVR. Therefore, in patients at high or very high VR, particularly those who have already experienced a vascular event, we continue to recommend strict achievement of LDL-C targets along with the ≥50% reduction in LDL-C from baseline in a single step and as soon as possible. Regardless of risk, smoking cessation, adopting a healthy lifestyle and a systolic blood pressure (SBP)<160 mmHg are recommended for all individuals.

For the first time, the guidelines present a new model for calculating risk – SCORE27 and SCORE2-OP8 – which has been calibrated for 4 European regions according to vascular mortality rates; Spain is one of the low VR countries. This tool allows calculation of the risk of vascular morbidity and mortality in the next 10 years (myocardial infarction, stroke, and vascular mortality) in men and women between 40 and 89 years of age. The coloured tables in the guidelines (using SBP, age, sex, smoking, and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) can be used, the European Society of Cardiology App or the tool available on the web (https://u-prevent.com), where total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol can be entered. These applications can also be used to calculate lifetime VR (LIFE-CV model) and the benefits of treatment in terms of years of life gained without vascular disease. In addition, there are specific tools for risk calculation in people with diabetes (ADVANCE risk score or DIAL model) and with established vascular disease (SMART REACH score or SMART REACH model).

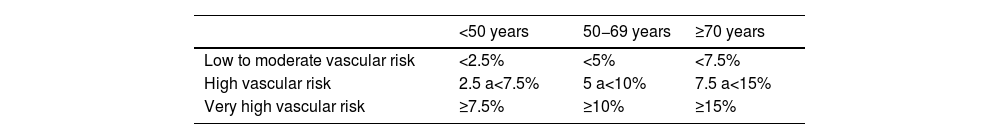

Vascular risk categories according to SCORE2/SCORE2-OP in apparently healthy peopleAnother substantial development is the establishment of different risk thresholds according to age, as shown in Table 1, in contrast to previous versions, which established a single risk threshold, to avoid undertreatment in young people and overtreatment in older people, as the long-term benefit of treating VR factors is greater in younger patients.

It is recommended that all very high-risk individuals should be treated, and treatment should be considered for those at high risk, based on risk modifiers, lifetime risk, treatment benefits and personal preferences.

The VR calculation and treatment algorithms for VR factors for apparently healthy individuals, patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease and patients with diabetes are presented in Figs. 1–3. Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) will be considered high or very high risk based on glomerular filtration rate and albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR). Patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia are considered high risk.

Vascular risk algorithm and therapeutic targets in apparently healthy patients. LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SCORE2, Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation 2; SCORE2-OP, Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation 2-Older Persons.

Therapeutic target and pharmacological treatment algorithm in patients with established vascular disease. LDL-C: Low density lipoprotein cholesterol; CV: cardiovascular; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DPI: dual pathway inhibition; CVD: cardiovascular disease; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Vascular risk algorithm, therapeutic objectives, and pharmacological treatment in patients with diabetes. CVD: cardiovascular disease; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DPI: dual pathway inhibition; GLP-1RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; HbAIc: glycosylated haemoglobin; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SBP: systolic blood pressure; SGLT2-i: sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; TOD: target organ damage.

The importance of communication with the patient is emphasised and an informed discussion of risk and therapeutic benefits, tailored to the needs of the individual, is recommended. In particular, the need for lifelong VR use is mentioned, especially in younger individuals, and the lifelong benefits after intervention or vascular age.

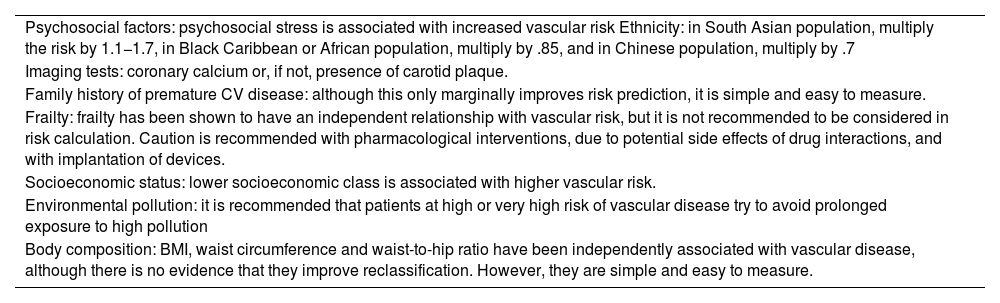

Risk modifiersFew risk modifiers meet the criteria to be considered in the VR calculation: to improve prediction (discrimination and reclassification), to have a clear public health impact (number of patients to be treated or screened) and to be feasible for implementation in clinical practice. The most relevant modifiers are summarised in Table 2.

Risk modifiers.

| Psychosocial factors: psychosocial stress is associated with increased vascular risk Ethnicity: in South Asian population, multiply the risk by 1.1−1.7, in Black Caribbean or African population, multiply by .85, and in Chinese population, multiply by .7 |

| Imaging tests: coronary calcium or, if not, presence of carotid plaque. |

| Family history of premature CV disease: although this only marginally improves risk prediction, it is simple and easy to measure. |

| Frailty: frailty has been shown to have an independent relationship with vascular risk, but it is not recommended to be considered in risk calculation. Caution is recommended with pharmacological interventions, due to potential side effects of drug interactions, and with implantation of devices. |

| Socioeconomic status: lower socioeconomic class is associated with higher vascular risk. |

| Environmental pollution: it is recommended that patients at high or very high risk of vascular disease try to avoid prolonged exposure to high pollution |

| Body composition: BMI, waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio have been independently associated with vascular disease, although there is no evidence that they improve reclassification. However, they are simple and easy to measure. |

BMI: body mass index; CV: cardiovascular.

The CEIPV has adapted the recommendations of the new guidelines based on those of the World Health Organisation and the Ministry of Health. They recommend:

- none-

Engaging in at least 150−300 min of moderate physical activity per week (or 75−150 min of vigorous activity or an equivalent combination of both) and performing muscle strengthening, bone mass improvement, and flexibility activities at least 2 days per week.9,10

- none-

Reducing sedentary periods, with breaks for activity every 1 h or 2 h, increasing active transport and limiting screen time.9,10

- none-

Eating a healthy and sustainable diet based on fresh, seasonal, and local foods: including at least 5 portions of fruit and vegetables a day, wholegrain cereals, prioritise vegetable protein (pulses, nuts) and fish, preferably oily fish, incorporating eggs, chicken, natural yoghurt, and milk in moderation, and avoiding red or processed meat, convenience foods, industrial pastries, and sugary drinks.11

- none-

Avoiding alcohol, as this is the only recommendation that avoids the risks associated with alcohol consumption. If consumed, the less the better, and always below the low-risk consumption limits: 10 g alcohol/day (one standard drink unit) in women and 20 g/day (2 standard drink units) in men,12 leaving a few days a week alcohol free and avoiding binge drinking; consumption should be completely avoided in children under 18 years of age and during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Cessation of tobacco use in all its forms, including tobacco products and related products such as e-cigarettes, and avoid of environmental exposure to tobacco smoke.

Developments in the treatment of risk factors in patients with vascular diseaseLipidsA stepwise approach to intensifying treatment is advised in otherwise healthy individuals with high or very high VR and in patients with vascular disease or diabetes, considering VR, treatment benefit, risk modifiers, co-morbidities, and personal preferences. In patients who have had vascular disease, in order to reach therapeutic LDL-C targets as soon as possible, it is recommended to proceed directly to step 2 (see section on VR). High-intensity statins are recommended in people at very high risk or with vascular disease, and if LDL-C targets are not achieved, ezetimibe should be added, and if targets are still not achieved, a PCSK9 inhibitor should be added. Although this recommendation agrees with meeting targets in 2 steps, it is difficult to achieve reductions≥50% in LDL-C, unless with maximal doses of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin. The available evidence suggests changing the terminology of “high-potency statins” to “high-intensity cholesterol-lowering therapy”.13 Thus, the first option in patients with high or very high VR could be to use non-maximal doses of statins (atorvastatin 40 mg or rosuvastatin 10 mg) associated with ezetimibe, which help therapeutic goals to be met with better tolerance and adherence. The addition of n-3 fatty acids (ethyl icosapentate 2 × 2 g/day) to statin therapy could be considered in high or very high-risk patients with mild/moderate hypertriglyceridaemia (triglyceride levels above 150 mg/dl).

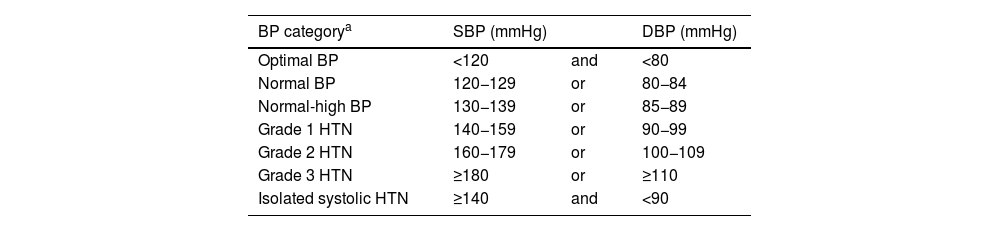

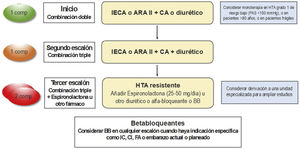

HypertensionIn contrast to the American guidelines (ACC/AHA 2017), the same classical threshold is still recommended to define hypertension (HTN), classifying it as optimal BP, normal BP, normal-high BP, and HT grades 1–3 (Table 3). The Spanish Society of Hypertension-Spanish League for Combating High Blood Pressure has already published a position paper justifying the desirability of maintaining this same cut-off point to define HTN.14

Classification of clinical BP (in consultation) according to clinical BP values.

| BP categorya | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal BP | <120 | and | <80 |

| Normal BP | 120−129 | or | 80−84 |

| Normal-high BP | 130−139 | or | 85−89 |

| Grade 1 HTN | 140−159 | or | 90−99 |

| Grade 2 HTN | 160−179 | or | 100−109 |

| Grade 3 HTN | ≥180 | or | ≥110 |

| Isolated systolic HTN | ≥140 | and | <90 |

BP for classification will be based on the mean of 2 or more readings, on 2 or more occasions, following standardised recommendations for quality measures. Subjects with systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in different categories will be classified in the highest category.

Current guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension (HTN) indicate the need to determine ambulatory BP levels by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring or self-measurement of blood pressure, given the high prevalence of white-coat and masked HTN.

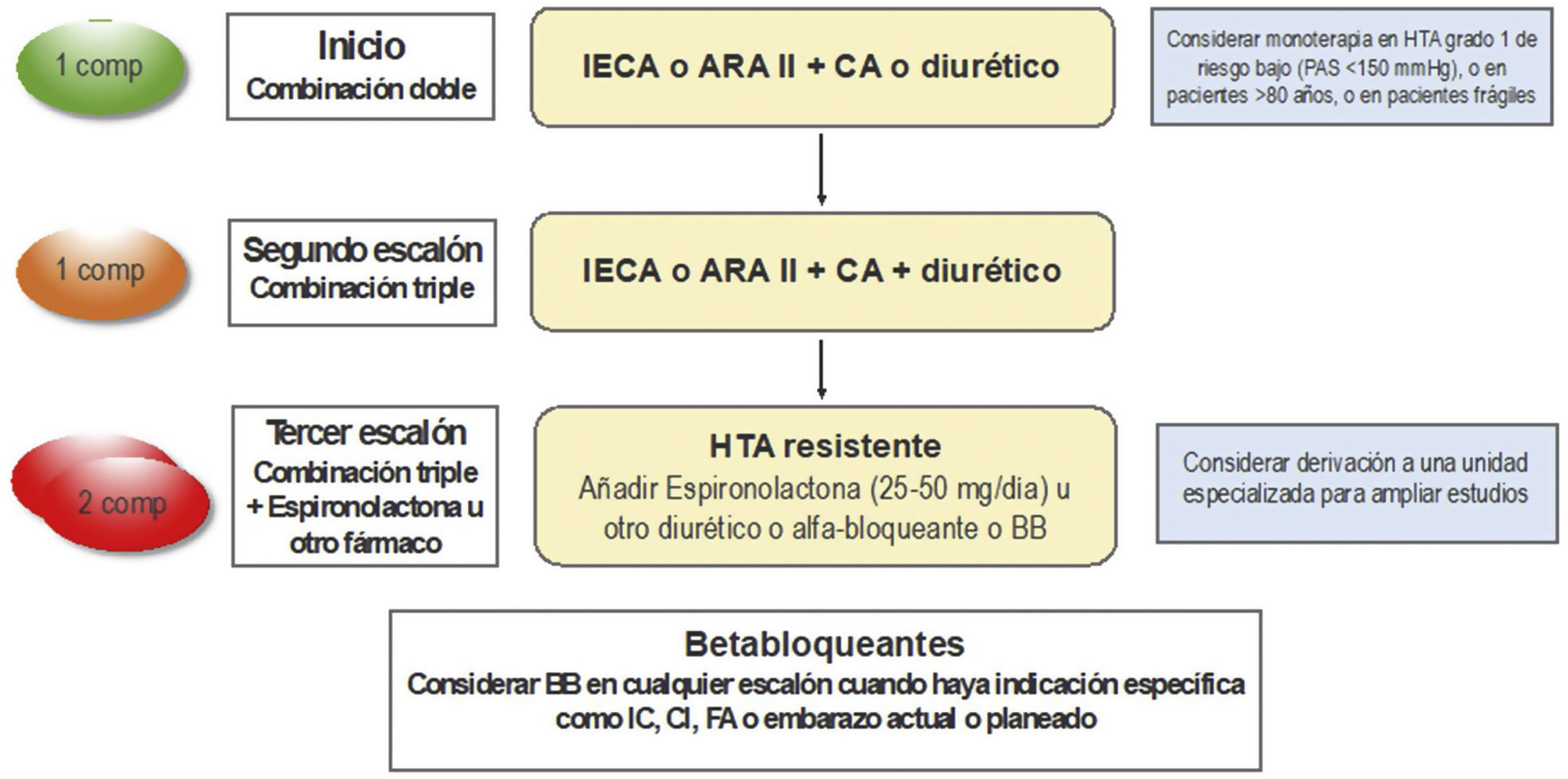

It is recommended to initiate treatment in individuals with grade 1 HTN considering VR, lifetime benefit, and the presence of target organ involvement. However, despite evidence of the benefit of lowering BP in reducing vascular morbidity and mortality, BP monitoring in Europe and other parts of the world is suboptimal, especially in low- and middle-income countries,15 and has worsened in recent years.16 Although the cause is multifactorial, poor adherence plays an important role. The recommended strategy for initial treatment remains the use of drug combinations, with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor antagonist in combination with a thiazide diuretic or a long half-life calcium antagonist (Fig. 4). A recent meta-analysis has shown that this strategy improves adherence and control rate in patients with HTN.17

Strategy to treat hypertension (HTN) without associated clinical complications. ACE inhibitor: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF: atrial fibrillation; ARA II: Angiotensin II receptor antagonists; BB: betablocker; CCB: calcium channel blocker; CHD: coronary heart disease; comp: compromised; HF: heart failure; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Metformin is recommended as first-line treatment of diabetes mellitus (DM) with monitoring of renal function, especially in patients without vascular disease, chronic renal failure, or heart failure. In these cases, in addition to the use or non-use of metformin, treatment with glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists type 1 or sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors type 2 that have demonstrated a reduction in vascular and renal events is recommended. In patients with DM and CKD, sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors are recommended due to their vascular and renal benefits. In patients with DM and reduced ejection fraction, sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors are recommended to reduce hospitalisation for heart failure and vascular deaths.

Chronic kidney diseaseCKD, as defined by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urine ACR, determines prognosis (Fig. 5). In patients without DM, an eGFR<30 ml/min/1.73 m2 or an eGFR 30−44 ml/min/1.73 m2 with an ACR>30 mg/g determines a very high risk of vascular events, in the same way as a previous vascular event. On the other hand, an eGFR of 30−44 ml/min/1.73 m2 and an ACR<30 mg/g or an eGFR of 45−59 ml/min/1. 73 m2 and an ACR of 30−300 mg/g, or an eGFR≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and an ACR>300 mg/g determines an elevated risk of vascular events.18 In patients with DM, severe target organ damage is considered to be an eFGR<45 ml/min/1.73 m2, or an eGFR of 45−59 ml/min/1.73 m2 and an ACR of 30−300 mg/g, or an ACR>300 mg/g; similarly, the presence of microvascular complications in 3 different sites confers a very high VR. In patients with CKD, general smoking cessation and improved lifestyle measures, SBP control targets between 130 and 140 mmHg and DBP<80 mmHg according to tolerance, and LDL-C targets less than 70 mg/dl or 55 mg/dl in patients with high or very high VR are recommended. In patients with DM and diabetic kidney disease, the use of hypoglycaemic drugs with recognised renal protective effects is recommended.

Chronic kidney disease related risk according to glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria categories. Areas in green: reference risk (no kidney disease if no other defining markers are present); areas in yellow: moderate risk; areas in orange: high risk; areas in red: very high risk.

*Albuminuria is expressed as albumin-creatinine ratio.

Guidelines Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes ‒KDIGO‒ on chronic kidney disease.

The addition of a second antithrombotic drug (P2Y12 platelet receptor inhibitor or low-dose rivaroxaban) to aspirin should be considered for secondary prevention of vascular disease in patients at high ischaemic and low haemorrhagic risk. Combination therapy with aspirin and low-dose rivaroxaban could be considered in patients with diabetes and peripheral arterial disease. Treatment with low-dose colchicine (.5 mg/day) could be considered in secondary prevention of vascular disease if other VR factors are inadequately controlled or in the case of recurrent ischaemic events despite optimal treatment.

Population-based prevention strategiesMuch greater emphasis is placed on health policy as a population-based prevention strategy. The aim is to reduce the attributable risk of risk factors, i.e., the burden of vascular disease that can be prevented by eliminating or reducing the prevalence of each factor. These strategies are based on Geoffrey Rose’s Prevention Paradox, according to which small shifts in the population distribution of risk factors to the left have a large impact on the overall burden of disease.19 Guidelines and other recommendations from international bodies such as the World Health Organisation20–23 propose the most cost-effective population-based interventions to create environments that promote healthy lifestyles by modifying risk factors such as physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, tobacco, and alcohol consumption,24 exposure to air and noise pollution25 (especially from road traffic), and by acting on climate change. In addition, different methods (governmental, media and education, labelling and information, financial incentives), settings (schools, workplace, community) and actions are described for each of them, supported with a level of evidence and a class of recommendation. The goal, and the task for national, regional, and local authorities, is to make a healthy lifestyle easy, creating environments where the default choices are health-promoting.

Recommendations for promoting physical activity and reducing sedentary lifestyles include urban planning measures to facilitate active and healthy mobility, active transport and increasing the availability of spaces and equipment that encourage physical activity in schools and community settings. To promote healthy eating, legislative measures are included to ban or reduce trans fats, reduce calorie intake, salt, added sugars and saturated fats in prepared foods and beverages, fiscal measures (taxation or incentives) on some foods and beverages, and availability of healthy meals on menus and in food vending machines in schools and workplaces. Recommendations, mainly legislative, are also included to reduce tobacco and alcohol consumption: regulation of consumption in public places, availability and sale, advertising, labelling and packaging, pricing policies, and the implementation of educational campaigns.21–26 Finally, measures are recommended to reduce emissions of small particles and gaseous pollutants, the use of solid fuels and road traffic, and to limit carbon dioxide emissions to reduce CV morbidity and mortality.

The population-based approach offers many benefits, such as reducing the gap in health inequalities, preventing other non-communicable diseases that have common risk factors and determinants with vascular events, such as cancer, lung disease, and type 2 DM, and saving the health and social costs of vascular events that have been prevented.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Brotons C, Camafort M, Castellanos MdM, Clarà A, Cortés O, Diaz Rodriguez A, et al. Comentario del CEIPV a las nuevas Guías Europeas de Prevención Cardiovascular 2021. Clin Investig Arterioscl. 2022;73:219–228.