Simulation is a valuable tool in health research, medical education and training of health personnel. Research and simulation-based education can focus on technical and non-technical skills needed to improve patient safety. This article comments on the effect of simulation on several outcomes, including those related to patient-safety during airway management.

La simulación es una valiosa herramienta en los procesos de investigación, educación médica y entrenamiento del personal de la salud. La investigación y la educación basa-das en la simulación pueden enfocarse en las habilidades técnicas y no técnicas necesarias para mejorar la seguridad del paciente. Este artículo de reflexión comenta aspectos relacionados al efecto de la simulación en diversos desenlaces, entre ellos los relacionados con la seguridad en el manejo de la vía aérea.

There are strong arguments in favor of simulation used for medical education and healthcare staff training. Exposure to real life patients is essential and necessary for the development of clinical skills; however, to accomplish high-quality performance and safety, there may be some risks inherent to the training process itself and the learning curves and skills. These risks can be minimized with the use of simulated models that mimic real life scenarios and its conditions. Consequently, simulation results in a safe environment where researchers and trainees may test and improve their personal and team skills. Furthermore, the use of simulation in research provides considerable benefits. It allows for exploring and describing the attitude of the various healthcare professionals or trainees and for evaluating the various technologies or devices under diverse scenarios and situations, free of risk for actual patients and with fewer ethical implications. By definition, simulation “is a technique, not a technology, that reflects or amplifies actual clinical experiences under participative guidance with an interactive approach”.1,2

Simulation-based training may potentially improve safety through a broad range of mechanisms, including: (1) routine training under emergency situations; (2) team training; (3) development of a sound environment to discuss mistakes without fear of recrimination; (4) safety and feasibility evaluation of new procedures; (5) evaluation of skills; (6) evaluation of the use of new devices; (7) human performance assessment; (8) acquisition of skills beyond the clinical context.3

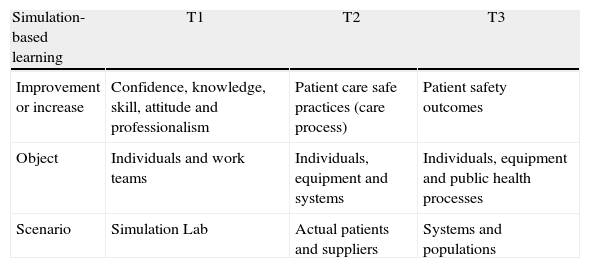

The literature reports the positive impact of simulation on the participant's knowledge, confidence during the procedures, teamwork performance, and process improvement within the simulation environment (simulated environment or T1). However, presently the data to support that simulation-based interventions resulting in safe outcomes for the individual patient or the population as a whole are scarce (actual patient scenario or T2; population or T3).3,4 McGaghie WC et al.5 present a classification of the outcomes to consider under each particular scenario described (Table 1).

| Simulation-based learning | T1 | T2 | T3 |

| Improvement or increase | Confidence, knowledge, skill, attitude and professionalism | Patient care safe practices (care process) | Patient safety outcomes |

| Object | Individuals and work teams | Individuals, equipment and systems | Individuals, equipment and public health processes |

| Scenario | Simulation Lab | Actual patients and suppliers | Systems and populations |

In the last few years there has been increasing evidence to support that simulation-based learning really improves the abilities of the staff trained, and the acquisition and retention of new skills.6 However, there are still few studies evaluating the process transition from T1 to T2.7 Crabtree et al. studied the correlation between a simulated scenario of fibrobronchoscopy intubation (T1) and the clinical skills in a real life situation (T2). Although no correlation was identified, the group concluded that the outcome used for the comparison (time to intubation) was not sensitive enough to detect improved performance during the procedure.8 Consequently, the outcomes where a simulation scenario may influence a trainee may be quite different, difficult to assess and quantify, and go beyond the usual outcomes analyzed by researchers. They may be summarized into technical and non-technical “attitudes and skills”, that require complex and validated measurement methods that are not yet widely available.9,10 For instance, some authors consider that attitudes and professionalism should be outcomes considered in the T1 scenarios.3,5 To approach simulation as a mere “transfer” of certain skills (measured for instance as the time to intubation) may be underestimating its value.

In the past issue of the Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology, Uribe et al. present a study that shows the efficacy to secure the airway (tracheal intubation) using the SALT supraglottic device (Supraglottic Airway Laryngopharyngeal tube). Ninety naïve participants were highly competent during their first intubation attempt (90%).11 In addition to their interesting findings and of the feasibility evidenced, this trial carried out under a simulated environment provided the participants with a wide range of abilities, different from those that the researchers studied as outcomes and classified as skills in scenario T1. Most of them were students that faced an intubation situation and their learning experience ranged from where to stand, the respect for a situation when the airway must be secured, to the performance of an expert during the teaching phase. There is no doubt that this experience (recreated within a research environment) was much more valuable for the participants. This is but one of the many advantages of simulation.12

Simulation has been widely used throughout the airway training process and despite the heterogeneity of the populations, the scenarios, and the interventions included in the study, the evidence as a whole supports the use of this tool for most of the outcomes studied.13,14 The benefits of acquiring skills for managing the airway far exceed its limitations. In a recent systematic review, Kennedy et al. document that simulation is superior to non-simulation teaching scenarios, including videos, conferences, or personal study and show the considerable impact of using simulation for learning and developing skills associated to airway management. Nevertheless, the authors fail to report the effect on future behaviors and on the patient's outcomes (though there is still a shortage of outcome data).15 Some authors defend the hypothesis that the impact on patient outcomes (considered the patient scenario or T2) may be appreciated in this context when structural changes are brought about in the education curricula rather than in individual procedures.15,16

Some research recently published in the Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology shows the boom of the research process within simulation scenarios for the airway and other teaching-learning environments.17,18 Certainly they become a national reference and a broad area for future investigation.

For further information and details about the advantages and disadvantages of simulation, Gómez LM published in the Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology an extensive review on simulation-based training and its implications for teaching and learning.12 Its impact on patient safety is further elaborated in the recent review by Naik VN et al.10

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Calvache JA. De la simulación a la seguridad en vía aérea. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2014;42:309–311.