There is a growing worldwide trend towards the consumption of nutritional supplements. Patients scheduled for surgery who are users of dietary supplements run the risk of interactions between these substances and drugs used in the perioperative period.

ObjectivesTo conduct a socio-demographic characterization, and determine the prevalence of nutritional supplement use in people taken to surgery; to offer a reference guideline for use during pre-anesthetic consultation.

MethodsThe research team conducted an observational descriptive and cross-sectional study of patients presenting to the pre-anesthetic consultation in thirteen cities; 1130 patients were asked about the use of these substances.

ResultsThe prevalence of use was 20.7%, higher among females at 62.8%, compared to males; consumption in people over 41 years was 63.2%; self-medication in 72.8%; increased consumption with age; in middle and high socioeconomic brackets, consumption was 63%; the higher the education, the higher the consumption; 36.6% plan to continue consumption despite the surgical procedure.

ConclusionsThe high rate of consumption of nutritional supplements in patients about to undergo surgery, possible drug interactions, and adverse effects of perioperative consumption of some herbs should trigger an alarm in the anesthesiologist performing the pre-anesthetic consultation; it is necessary to include this in the interview and act accordingly. We recommend always asking to see product packaging.

Hay una creciente tendencia mundial hacia el consumo de suplementos nutricionales. Los pacientes que consumen dichas sustancias y que van a ser llevados a cirugía tienen un riesgo potencial de presentar interacciones medicamentosas entre estas sustancias y los medicamentos del período perioperatorio.

ObjetivosRealizar una caracterización sociodemográfica y determinar la prevalencia del consumo de suplementos nutricionales en personas que van a ser llevadas a cirugía; además, servir como guía de consulta para tomar conductas en la consulta preanestésica.

MetodologíaSe llevó a cabo un estudio observacional descriptivo de corte transversal, con pacientes que se presentaban a la consulta preanestésica, en 13 ciudades del país. A 1.130 pacientes se les interrogó acerca del consumo de estas sustancias.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de consumo fue de un 20,7%, siendo mayor en el sexo femenino, con un 62,8%, frente al sexo masculino; el consumo en personas mayores de 41 años fue del 63,2%; se automedicaron un 72,8%; a mayor edad, mayor consumo; entre los estratos medio y alto el consumo fue del 63%; a mayor nivel educativo, más consumo; el 36,6% piensan seguir consumiendo a pesar del procedimiento.

ConclusionesEl alto índice de consumo de suplementos nutricionales en pacientes que van a someterse a una cirugía, las posibles interacciones con los medicamentos del perioperatorio y los efectos adversos de algunas hierbas medicinales deben poner en alerta el anestesiólogo que realiza la consulta preanestésica; es necesario incluir este tema en el interrogatorio y tomar conductas al respecto. Es aconsejable solicitar los empaques de los productos que consume.

Technological developments in medicine at the present time occur at dizzying speed and research brings about amazing breakthroughs year after year regarding new therapies for a broad range of diseases.

Notwithstanding, a growing number of people resort to alternative, non-conventional practices such as acupuncture, homeopathy, herbal therapies and dietary supplements used as nutritional add-ons to their normal diets.1

This has come about because people want to have better control over their health. In contrast with medications, dietary supplements are not subject to rigorous evaluations before they reach the market.2 One out of every six patients takes some type of dietary supplement concomitantly with medications prescribed by their physicians. All kinds of supplements are found in drugstores, supermarkets, local stores, etc., and patients are now able to find abundant information on the web. However, most of them fail to mention the use of these substances to their physicians, placing their life at risk as a result of potential interactions. It is estimated that 70% of patients fail to inform their physician3 and many of them even take mixes of drugs and nutritional supplements containing substances with unknown side effects that might interact with perioperative medications and result in adverse events.4

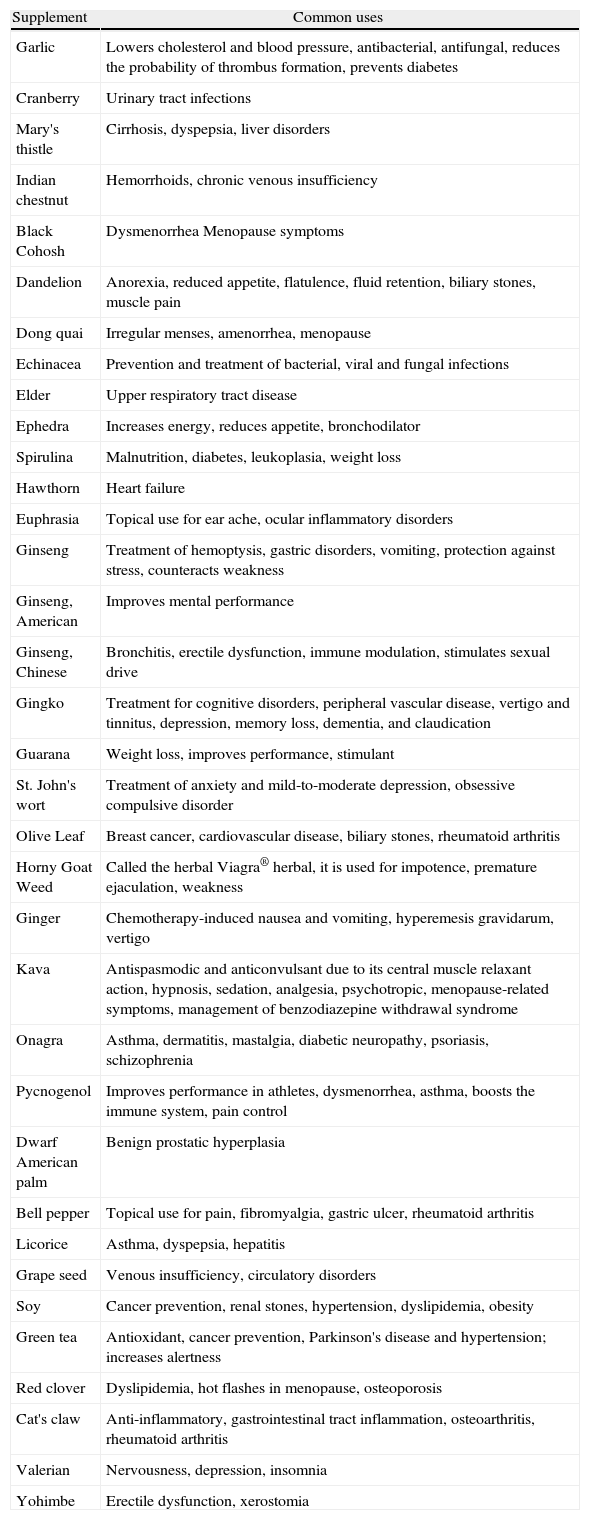

Many companies promote herbal medications as dietary supplements. It is estimated that this is a 19 billion-dollar industry and that almost half of the Americans take daily supplements, only some of which have proven efficacy.5 According to a report published in 2009 in the United States regarding consumer trust in dietary supplements, 84% of people trust the quality, safety and efficacy claims of these products.6Table 1 shows the common uses of various substances.

Common uses of various substances.

| Supplement | Common uses |

| Garlic | Lowers cholesterol and blood pressure, antibacterial, antifungal, reduces the probability of thrombus formation, prevents diabetes |

| Cranberry | Urinary tract infections |

| Mary's thistle | Cirrhosis, dyspepsia, liver disorders |

| Indian chestnut | Hemorrhoids, chronic venous insufficiency |

| Black Cohosh | Dysmenorrhea Menopause symptoms |

| Dandelion | Anorexia, reduced appetite, flatulence, fluid retention, biliary stones, muscle pain |

| Dong quai | Irregular menses, amenorrhea, menopause |

| Echinacea | Prevention and treatment of bacterial, viral and fungal infections |

| Elder | Upper respiratory tract disease |

| Ephedra | Increases energy, reduces appetite, bronchodilator |

| Spirulina | Malnutrition, diabetes, leukoplasia, weight loss |

| Hawthorn | Heart failure |

| Euphrasia | Topical use for ear ache, ocular inflammatory disorders |

| Ginseng | Treatment of hemoptysis, gastric disorders, vomiting, protection against stress, counteracts weakness |

| Ginseng, American | Improves mental performance |

| Ginseng, Chinese | Bronchitis, erectile dysfunction, immune modulation, stimulates sexual drive |

| Gingko | Treatment for cognitive disorders, peripheral vascular disease, vertigo and tinnitus, depression, memory loss, dementia, and claudication |

| Guarana | Weight loss, improves performance, stimulant |

| St. John's wort | Treatment of anxiety and mild-to-moderate depression, obsessive compulsive disorder |

| Olive Leaf | Breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, biliary stones, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Horny Goat Weed | Called the herbal Viagra® herbal, it is used for impotence, premature ejaculation, weakness |

| Ginger | Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, hyperemesis gravidarum, vertigo |

| Kava | Antispasmodic and anticonvulsant due to its central muscle relaxant action, hypnosis, sedation, analgesia, psychotropic, menopause-related symptoms, management of benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome |

| Onagra | Asthma, dermatitis, mastalgia, diabetic neuropathy, psoriasis, schizophrenia |

| Pycnogenol | Improves performance in athletes, dysmenorrhea, asthma, boosts the immune system, pain control |

| Dwarf American palm | Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

| Bell pepper | Topical use for pain, fibromyalgia, gastric ulcer, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Licorice | Asthma, dyspepsia, hepatitis |

| Grape seed | Venous insufficiency, circulatory disorders |

| Soy | Cancer prevention, renal stones, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity |

| Green tea | Antioxidant, cancer prevention, Parkinson's disease and hypertension; increases alertness |

| Red clover | Dyslipidemia, hot flashes in menopause, osteoporosis |

| Cat's claw | Anti-inflammatory, gastrointestinal tract inflammation, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Valerian | Nervousness, depression, insomnia |

| Yohimbe | Erectile dysfunction, xerostomia |

In 1994, the US Congress passed a law defining dietary supplements as substances mainly for oral intake containing, as their main characteristic, a “dietary ingredient” designed to supplement the diet. Some examples of dietary supplements are vitamins, minerals, herbs (alone or in a mix), aminoacids, and food components such as enzymes and gland extracts. They come in different presentations including tablets, soft gels, liquids and powders. They are not presented as food substitutes or as meal replacements, and they are labeled as dietary supplements.7 On the other hand, nutraceuticals are dietary supplements containing a concentrated form of a bioactive substance originally derived from a food source but now present in a non-food matrix, used as health enhancers at higher doses than those found in normal foods.8

Tsen et al.9 showed that up to 32% of patients assessed during the pre-operative phase used dietary supplements, herbal products, or both. Effects associated with plant-derived products include pharmacokinetic alterations (alteration of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and clearance of conventional medications; pharmacodynamic alterations; and direct interactions with drugs.10

Dickinson et al.3 surveyed cardiologist, dermatologists and orthopedic surgeons in order to determine if they used dietary supplements and recommended them to their patients. They found that up to 75% of them used supplements and up to 91% recommended their use in situations related to their specialties, for example, lowering cholesterol, reducing joint pain, anxiety, etc. They recommended substances such as omega-3 oil, calcium, vitamins and glucosamine. Noteworthy is the concern of these professionals for the absence of continuing education courses on this subject. Table 1 shows a list of the most common uses of some dietary supplements.

The objective of this work was to perform a socio-demographic characterization, determine the prevalence of the use of dietary supplements in patients who are going to be taken to surgery and receive a pre-anesthesia assessment, and to offer a consultation guideline to help anesthesiologists take action during the pre-anesthesia assessment.

Materials and methodsDesignA descriptive cross-sectional study was proposed in order to determine the prevalence of dietary supplement use.

Population and sampleA sample was taken at the investigator's convenience in those cities where the cooperative (ANESTECOOP) operates.

ProcedureData were collected through interviews conducted by anesthesiologists during the pre-anesthesia consultation, and recorded in a format designed for that purpose. The interviews were conducted in 13 cities of the country (Pereira, Valledupar, Apartadó, Cartago, Sincelejo, Armenia, Bogotá, Montería, Buga, Manizales, Riohacha, Cali, La Dorada), totaling 1248 patients interviewed in the pre-anesthesia assessment. Of that total, 1130 were taken into account for analysis and the remaining 118 were excluded for different reasons (incomplete or illegible surveys, etc.).

VariablesThey correspond to the questions in the survey, which in turn match each of the specific objectives.

Inclusion criteriaPatients over 18 years of age scheduled for elective surgery of any type attending the preoperative consultation.

Statistical analysisFrequencies were performed for the qualitative variables together with a bivariate analysis using chi2, with a statistical significance value of 0.05. The only quantitative variable (age) was analyzed using means and standard deviations and then recoded in ranges. Prevalence was determined and results were contrasted with the data of the NHANES 2002 and 2008 surveys.

Ethical considerationsThis is a descriptive observational study based on interviews for which a verbal consent was obtained from the patients. A form was used to record data pertaining to the study and there was no experimentation with the patients at any time; there were no physical examination or biochemical measurements; hence, the Helsinki declaration does not apply.

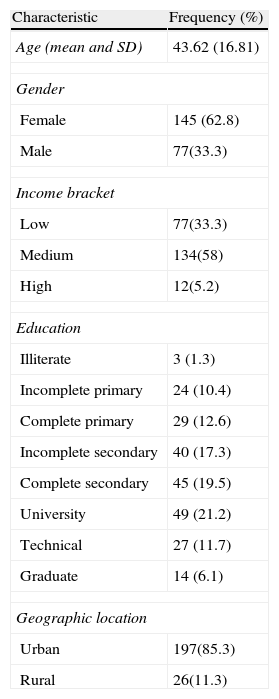

Results and analysisIt was determined that the prevalence of dietary supplement use was 20.7%, with a higher consumption among females (62.8%) compared to males. By age group, the higher consumption was found between 41 and 60 years (39.8%); in patients over 60 years of age, the rate was 23.4%, for an overall consumption of 63.2% in adults over 41. Table 2 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the surveyed population.

Socio-demographic characteristics of individuals who use dietary supplements.

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

| Age (mean and SD) | 43.62 (16.81) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 145 (62.8) |

| Male | 77(33.3) |

| Income bracket | |

| Low | 77(33.3) |

| Medium | 134(58) |

| High | 12(5.2) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 3 (1.3) |

| Incomplete primary | 24 (10.4) |

| Complete primary | 29 (12.6) |

| Incomplete secondary | 40 (17.3) |

| Complete secondary | 45 (19.5) |

| University | 49 (21.2) |

| Technical | 27 (11.7) |

| Graduate | 14 (6.1) |

| Geographic location | |

| Urban | 197(85.3) |

| Rural | 26(11.3) |

Consumption prevalence according to level of education was distributed as follows: complete primary education, 24.2%; complete secondary education, 36.7%; and 39% among patients with technical, university or graduate education.

Consumption prevalence in income brackets 1 and 2 (lower) was 34.5%, 60.1% in income brackets 3 and 4 (middle), and 5.4% in income brackets 5 and 6 (upper); of the patients surveyed, 88.3% came from the urban area.

To the question of how they had started using these products, 72.8% reported self-medication and the remaining 27.2% reported medical recommendation; 51.9% had started using supplements on a recommendation from a friend or relative.

When asked about the reasons for using nutritional supplements, 44.5% of the respondents reported that they were healthy but wanted to supplement their diets, and 33.7% reported illness and the desire to improve their health. Another reason, given by 8.6% was the feeling of fatigue.

To the question of how long they had been using supplements, 50.5% reported between three and six months, 30% reported 7–12 months, and the remaining 19.5% reported more than one year.

Bearing in mind that patients in the pre-anesthesia consultation are going to undergo surgery, to the question of whether they were planning to stop using the product, or interrupt its use temporarily, or if they were planning to continue to use it despite the procedure, 22.6%, 40.8% and 36.6%, respectively, gave a positive response.

In the bivariate analysis, a statistically significant association was found between consumption and age, income bracket, gender and level of education. It was found that, the older the age the higher the consumption, the higher the income bracket the higher the consumption (63% among people in middle and upper income brackets); there was higher consumption among females, and higher consumption also among people with a higher level of education.

As far as the different substances used as dietary supplements, a wide range of products were reported with close to 200 different responses including Green tea, multivitamins, folic acid, omega-3, glycerine, beta carotene, guarana, gingko biloba, valerian, duck embryos, artichokes, soy, spirulina, transfer factors, shark cartilage, ginseng, plus a whole variety of brand names.

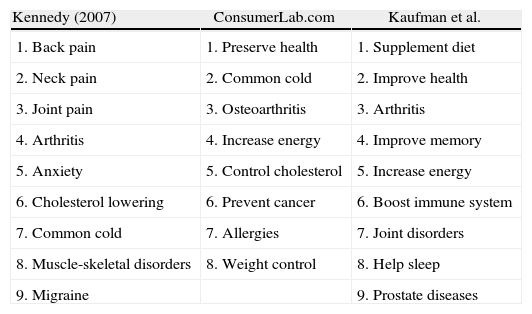

DiscussionAdverse reactions to herbal medicines and supplements are not well recognized and, what is even worse, not reported. Most of the people using dietary supplements do not stop using conventional medications prescribed by their physicians.11 Even more difficult than detecting adverse reactions to medications, is detecting adverse reactions to dietary supplements. It is important to set up a system of reporting and follow-up of potential interactions and adverse reactions caused by these substances in order to be able to evaluate these products and create policies regarding their use.7Table 3 summarizes the main reasons why the general population uses these products, as determined by three independent studies; it shows that the reasons are similar to those found in this research, and points to the fact that most people hope to improve their health and start using these substances without thinking about potential interactions with medications they may be taking at the same time.

Reasons for consuming dietary supplements.

| Kennedy (2007) | ConsumerLab.com | Kaufman et al. |

| 1. Back pain | 1. Preserve health | 1. Supplement diet |

| 2. Neck pain | 2. Common cold | 2. Improve health |

| 3. Joint pain | 3. Osteoarthritis | 3. Arthritis |

| 4. Arthritis | 4. Increase energy | 4. Improve memory |

| 5. Anxiety | 5. Control cholesterol | 5. Increase energy |

| 6. Cholesterol lowering | 6. Prevent cancer | 6. Boost immune system |

| 7. Common cold | 7. Allergies | 7. Joint disorders |

| 8. Muscle-skeletal disorders | 8. Weight control | 8. Help sleep |

| 9. Migraine | 9. Prostate diseases |

Two studies conducted in 200012 in pre-surgical patients reported that almost half of those patients used dietary supplements. The biggest source of concern though, is that patients rarely offer this information and, worse still, anesthesiologists rarely ask about it. Later on, in 2004, MacKichan et al. asked about the reasons why patients do not discuss the use of these substances with their physicians, and found the following answers: products are labeled as natural and therefore they assume that they are safe; a medical prescription is not required; they are not considered medications. This study found that 72.8% of people using supplements simply self-medicate, and perhaps the argument for not asking their physicians, as was found in the previous studies, is that the products are labeled as natural and they assume they are safe.10

Some statistics show that close to 50% of the patients undergoing surgery discontinue the use of dietary supplements on their own. Consequently, the obvious conclusion is that the other 50% continues to use them.2 In our case, the result is somewhat different, as we found that only 22.6% of the people who use these products think about interrupting their use before the surgery. This reinforces the idea of the sense of trust regarding dietary supplements.

There is an association between use and age over 41, female gender, upper socio-economic bracket, and higher level of education. This may be due to the fact that, the higher the level of education, the higher the purchasing power and the higher the income bracket. Leung et al., reported similar results in 2000, in a study similar to ours: 39.2% used some form of supplement; 56.4% did not mention the use of these products to their treating physician; 53% planned to discontinue their use before surgery. The authors report the following variables as associated with the use of dietary supplements: female gender, high income, high education level, and age range between 39 and 45 years.2

NHANES, The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey is a representative survey conducted nationwide in the United States. It comprises medical exams and tests, as well as detailed questions about respondent health, lifestyle and diet, and also the use of dietary supplements. The results of this survey in 2002 showed an association between the use of dietary supplements and a high level of education and age over 60. Of the respondents, 16.8% used four or more types of supplements,13 with results similar to ours.

The NHANES 2008 survey16 estimated the use of complementary and alternative medicine among American adults and children. They used data from prior surveys conducted by the CDC and also compared the data with the 2002 survey. They found that 4 out of every 10 adults and 1 out of every 9 children used this type of medicine.

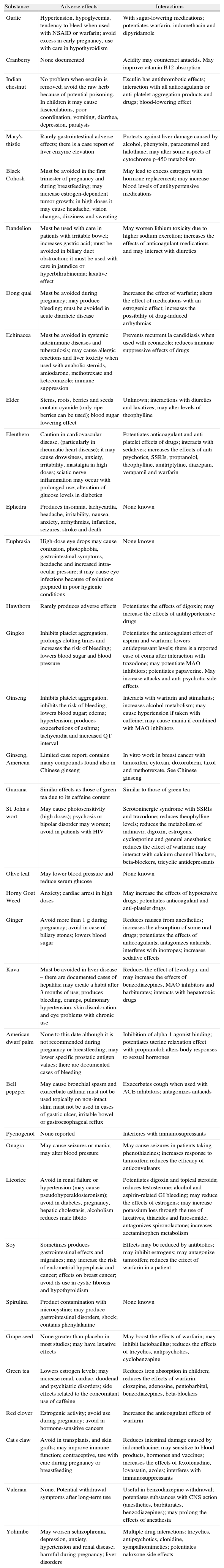

Hogg et al. used a survey in United Kingdom hospitals to ask whether they had specific policies or protocols for managing patients who were taking herbal medicines during the perioperative period, and they found that 90% of the participating institutions had none.4 The situation may be the same in the hospitals in our country. Table 4 shows adverse reactions and interactions of the most commonly used dietary supplements.

Commonly used supplements, adverse effects and interactions.

| Substance | Adverse effects | Interactions |

| Garlic | Hypertension, hypoglycemia, tendency to bleed when used with NSAID or warfarin; avoid excess in early pregnancy, use with care in hypothyroidism | With sugar-lowering medications; potentiates warfarin, indomethacin and dipyridamole |

| Cranberry | None documented | Acidity may counteract antacids. May improve vitamin B12 absorption |

| Indian chestnut | No problem when esculin is removed; avoid the raw herb because of potential poisoning. In children it may cause fasciculations, poor coordination, vomiting, diarrhea, depression, paralysis | Esculin has antithrombotic effects; interaction with all anticoagulants or anti-platelet aggregation products and drugs; blood-lowering effect |

| Mary's thistle | Rarely gastrointestinal adverse effects; there is a case report of liver enzyme elevation | Protects against liver damage caused by alcohol, phenytoin, paracetamol and halothane; may alter some aspects of cytochrome p-450 metabolism |

| Black Cohosh | Must be avoided in the first trimester of pregnancy and during breastfeeding; may increase estrogen-dependent tumor growth; in high doses it may cause headache, vision changes, dizziness and sweating | May lead to excess estrogen with hormone replacement; may increase blood levels of antihypertensive medications |

| Dandelion | Must be used with care in patients with irritable bowel; increases gastric acid; must be avoided in biliary duct obstruction; it must be used with care in jaundice or hyperbilirubinemia; laxative effect | May worsen lithium toxicity due to higher sodium excretion; increases the effects of anticoagulant medications and may interact with diuretics |

| Dong quai | Must be avoided during pregnancy; may produce bleeding; must be avoided in acute diarrheic disease | Increases the effect of warfarin; alters the effect of medications with an estrogenic effect; increases the possibility of drug-induced arrhythmias |

| Echinacea | Must be avoided in systemic autoimmune diseases and tuberculosis; may cause allergic reactions and liver toxicity when used with anabolic steroids, amiodarone, methotrexate and ketoconazole; immune suppression | Prevents recurrent la candidiasis when used with econazole; reduces immune suppressive effects of drugs |

| Elder | Stems, roots, berries and seeds contain cyanide (only ripe berries can be used); blood sugar lowering effect | Unknown; interactions with diuretics and laxatives; may alter levels of theophylline |

| Eleuthero | Caution in cardiovascular disease, (particularly in rheumatic heart disease); it may cause drowsiness, anxiety, irritability, mastalgia in high doses; sciatic nerve inflammation may occur with prolonged use; alteration of glucose levels in diabetics | Potentiates anticoagulant and anti-platelet effects of drugs; interacts with sedatives; increases the effects of anti-psychotics, SSRIs, propranolol, theophylline, amitriptyline, diazepam, verapamil and warfarin |

| Ephedra | Produces insomnia, tachycardia, headache, irritability, nausea, anxiety, arrhythmias, infarction, seizures, stroke and death | None known |

| Euphrasia | High-dose eye drops may cause confusion, photophobia, gastrointestinal symptoms, headache and increased intra-ocular pressure; it may cause eye infections because of solutions prepared in poor hygienic conditions | None known |

| Hawthorn | Rarely produces adverse effects | Potentiates the effects of digoxin; may increase the effects of antihypertensive drugs |

| Gingko | Inhibits platelet aggregation, prolongs clotting times and increases the risk of bleeding; lowers blood sugar and blood pressure | Potentiates the anticoagulant effect of aspirin and warfarin; lowers antidepressant levels; there is a reported case of coma after interaction with trazodone; may potentiate MAO inhibitors; potentiates papaverine. May increase attacks and anti-psychotic side effects |

| Ginseng | Inhibits platelet aggregation, inhibits the risk of bleeding; lowers blood sugar; edema; hypertension; produces exacerbations of asthma; tachycardia and increased QT interval | Interacts with warfarin and stimulants; increases alcohol metabolism; may cause hypertension if taken with caffeine; may cause mania if combined with MAO inhibitors |

| Ginseng, American | Limited case report; contains many compounds found also in Chinese ginseng | In vitro work in breast cancer with tamoxifen, cytoxan, doxorubicin, taxol and methotrexate. See Chinese ginseng |

| Guarana | Similar effects as those of green tea due to its caffeine content | Similar to those of green tea |

| St. John's wort | May cause photosensitivity (high doses); psychosis or bipolar disorder may worsen; avoid in patients with HIV | Serotoninergic syndrome with SSRIs and trazodone; reduces theophylline levels; reduces the metabolism of indinavir, digoxin, estrogens, cyclosporine and general anesthetics; reduces the effect of warfarin; may interact with calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, tricyclic antidepressants |

| Olive leaf | May lower blood pressure and reduce serum glucose | None known |

| Horny Goat Weed | Anxiety; cardiac arrest in high doses | May increase the effects of hypotensive drugs; potentiates anticoagulant and anti-platelet drugs |

| Ginger | Avoid more than 1g during pregnancy; avoid in case of biliary stones; lowers blood sugar | Reduces nausea from anesthetics; increases the absorption of some oral drugs; potentiates the effects of anticoagulants; antagonizes antacids; interferes with inotropes; increases sedative effects |

| Kava | Must be avoided in liver disease – there are documented cases of hepatitis; may create a habit after 3 months of use; produces bleeding, cramps, pulmonary hypertension, skin discoloration, and eye problems with chronic use | Reduces the effect of levodopa, and may increase the effects of benzodiazepines, MAO inhibitors and barbiturates; interacts with hepatotoxic drugs |

| American dwarf palm | None to this date although it is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding; may lower specific prostatic antigen values; there are documented cases of bleeding | Inhibition of alpha-1 agonist binding; potentiates uterine relaxation effect with propranolol; alters body responses to sexual hormones |

| Bell pepzper | May cause bronchial spasm and exacerbate asthma; must not be used topically on non-intact skin; must not be used in cases of gastric ulcer, irritable bowel or gastroesophageal reflux | Exacerbates cough when used with ACE inhibitors; antagonizes antacids |

| Pycnogenol | None reported | Interferes with immunosupressants |

| Onagra | May cause seizures or mania; may alter blood pressure | May cause seizures in patients taking phenothiazines; increases response to tamoxifen; reduces the efficacy of anticonvulsants |

| Licorice | Avoid in renal failure or hypertension (may cause pseudohyperaldosteronism); avoid in diabetes, pregnancy, hepatic cholestasis, alcoholism reduces male libido | Potentiates digoxin and topical steroids; reduces testosterone; alcohol and aspirin-related GI bleeding; may reduce the effects of estrogens; may increase potassium loss through the use of laxatives, thiazides and furosemide; antagonizes spironolactone; increases acetaminophen metabolism |

| Soy | Sometimes produces gastrointestinal effects and migraines; may increase the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer; effects on breast cancer; avoid its use in cystic fibrosis and hypothyroidism | Effects may be reduced by antibiotics; may inhibit estrogens; may antagonize tamoxifen; reduces the effect of warfarin in a patient |

| Spirulina | Product contamination with microcystine; may produce gastrointestinal disorders, shock; contains phenylalanine | None known |

| Grape seed | None greater than placebo in most studies; may have laxative effects | May boost the effects of warfarin; may inhibit lactobacillus; reduces the effects of tricyclics, antipsychotics, cyclobenzapine |

| Green tea | Lowers estrogen levels; may increase renal, cardiac, duodenal and psychiatric disorders; side effects related to the concomitant use of caffeine | Reduces iron absorption in children; reduces the effects of warfarin, clozapine, adenosine, pentobarbital, benzodiazepines, beta-blockers |

| Red clover | Estrogenic activity; avoid use during pregnancy; avoid in hormone-sensitive cancers | Increases the anticoagulant effects of warfarin |

| Cat's claw | Avoid in transplants, and skin grafts; may improve immune function; contraceptive, use with care during pregnancy or breastfeeding | Reduces intestinal damage caused by indomethacine; may sensitize to blood products, hormones and vaccines; increases the effects of fexofenadine, lovastatin, azoles; interferes with immunosuppressants |

| Valerian | None. Potential withdrawal symptoms after long-term use | Useful in benzodiazepine withdrawal; potentiates substances with CNS action (anesthetics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines); may prolong the effects of anesthesia |

| Yohimbe | May worsen schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, hypertension and renal disease; harmful during pregnancy; liver disorders | Multiple drug interactions: tricyclics, antipsychotics, clonidine, sympathomimetics; potentiates naloxone side effects |

We submit this paper not only as the product of a research process but also as study material and guideline for the country's anesthesiologists. It is important to ask these questions of our patients and try to determine, as accurately as possible, what substances they are consuming, how these can affect the planned procedure, and how to act, not only for the benefit of the patients but also for our own peace of mind. There are reports in the literature about serious adverse events when these substances are associated with anesthetic agents. This is one of the few studies conducted in Colombia in relation to the intake of nutritional supplements prior to a surgical intervention.

The lack of sound studies plus the absence of knowledge regarding the effectiveness of these products, creates a false sense of reassurance. The use of these products becomes a challenge for healthcare providers, in particular with patients going to surgery, considering that interactions between some supplements and anesthetic drugs may be fatal.10 Education to the public is required in order to avoid abuse of these substances, self-medication and the false belief that natural products are free from adverse effects.

The following is a list of general recommendations for anesthesiologists8,15,16,18,19:

- 1.

Always ask about the use of supplements and herbal medicine and turn this into a habit as part of the routine patient interview.

- 2.

Always document patient use of supplements in the clinical record.

- 3.

Discontinue supplements in cases of pregnancy and breastfeeding.

- 4.

Ask patients to bring (physically) all medications and supplements that they are using.

- 5.

Evaluate the components in the supplements used by the patient at the time, and consider potential adverse reactions and drug interactions.

- 6.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends discontinuation of these substances two weeks before elective surgery.

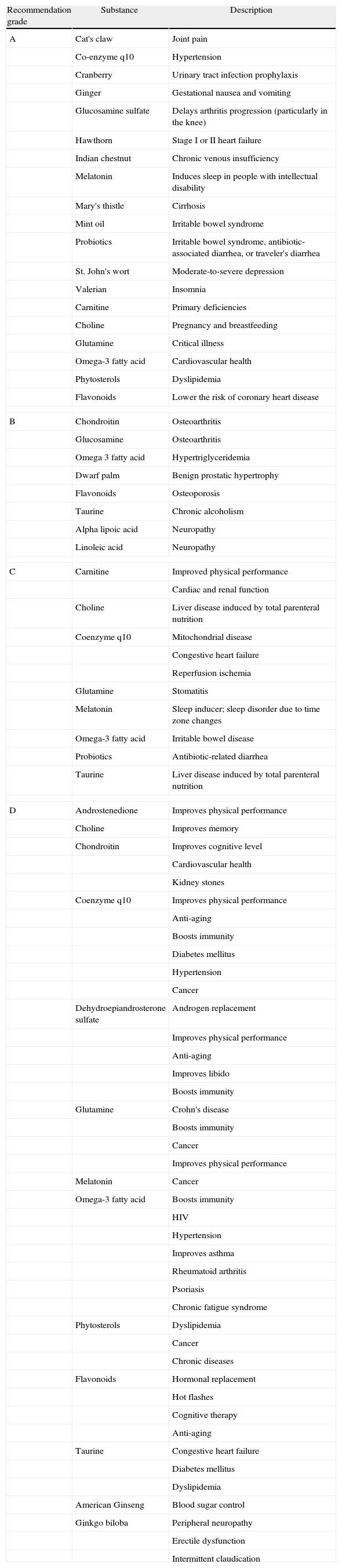

Table 5 shows evidence-based recommendations for the use of some dietary supplements.8

Evidence-based recommendations for the use of some dietary supplements.

| Recommendation grade | Substance | Description |

| A | Cat's claw | Joint pain |

| Co-enzyme q10 | Hypertension | |

| Cranberry | Urinary tract infection prophylaxis | |

| Ginger | Gestational nausea and vomiting | |

| Glucosamine sulfate | Delays arthritis progression (particularly in the knee) | |

| Hawthorn | Stage I or II heart failure | |

| Indian chestnut | Chronic venous insufficiency | |

| Melatonin | Induces sleep in people with intellectual disability | |

| Mary's thistle | Cirrhosis | |

| Mint oil | Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Probiotics | Irritable bowel syndrome, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, or traveler's diarrhea | |

| St. John's wort | Moderate-to-severe depression | |

| Valerian | Insomnia | |

| Carnitine | Primary deficiencies | |

| Choline | Pregnancy and breastfeeding | |

| Glutamine | Critical illness | |

| Omega-3 fatty acid | Cardiovascular health | |

| Phytosterols | Dyslipidemia | |

| Flavonoids | Lower the risk of coronary heart disease | |

| B | Chondroitin | Osteoarthritis |

| Glucosamine | Osteoarthritis | |

| Omega 3 fatty acid | Hypertriglyceridemia | |

| Dwarf palm | Benign prostatic hypertrophy | |

| Flavonoids | Osteoporosis | |

| Taurine | Chronic alcoholism | |

| Alpha lipoic acid | Neuropathy | |

| Linoleic acid | Neuropathy | |

| C | Carnitine | Improved physical performance |

| Cardiac and renal function | ||

| Choline | Liver disease induced by total parenteral nutrition | |

| Coenzyme q10 | Mitochondrial disease | |

| Congestive heart failure | ||

| Reperfusion ischemia | ||

| Glutamine | Stomatitis | |

| Melatonin | Sleep inducer; sleep disorder due to time zone changes | |

| Omega-3 fatty acid | Irritable bowel disease | |

| Probiotics | Antibiotic-related diarrhea | |

| Taurine | Liver disease induced by total parenteral nutrition | |

| D | Androstenedione | Improves physical performance |

| Choline | Improves memory | |

| Chondroitin | Improves cognitive level | |

| Cardiovascular health | ||

| Kidney stones | ||

| Coenzyme q10 | Improves physical performance | |

| Anti-aging | ||

| Boosts immunity | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||

| Hypertension | ||

| Cancer | ||

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate | Androgen replacement | |

| Improves physical performance | ||

| Anti-aging | ||

| Improves libido | ||

| Boosts immunity | ||

| Glutamine | Crohn's disease | |

| Boosts immunity | ||

| Cancer | ||

| Improves physical performance | ||

| Melatonin | Cancer | |

| Omega-3 fatty acid | Boosts immunity | |

| HIV | ||

| Hypertension | ||

| Improves asthma | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Psoriasis | ||

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | ||

| Phytosterols | Dyslipidemia | |

| Cancer | ||

| Chronic diseases | ||

| Flavonoids | Hormonal replacement | |

| Hot flashes | ||

| Cognitive therapy | ||

| Anti-aging | ||

| Taurine | Congestive heart failure | |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||

| Dyslipidemia | ||

| American Ginseng | Blood sugar control | |

| Ginkgo biloba | Peripheral neuropathy | |

| Erectile dysfunction | ||

| Intermittent claudication | ||

| Level of evidence-description | Detail |

| Levels of evidence | |

| 1. Large prospective, randomized, controlled trials | Data derived from a significant number of adequately powered trials. Large meta-analyses with raw or clustered data. Consistent finding pattern in the population for which the recommendation is made |

| 2. Randomized, controlled, prospective trials in small populations | Limited number of trials, with small population sizes. Only one well-conducted prospective cohort study. Limited but well performed meta-analysisInconsistent findings or results that cannot be generalized to the population |

| 3. Outcomes of other types of experimental or non-experimental studies | Non-randomized or controlled trialsNon-controlled or poorly controlled trialsAny randomized clinical trial with a high risk of biasRetrospective or observational data.Contradictory data that cannot support a final recommendation |

| 4. Expert opinion | Shortage of data for inclusion in the categories above; literature summary by an expert panelExperience based on the information |

| Grade | Description | Detail |

| Recommendation grade | ||

| A | Conclusive level 1 publications showing that benefit is greater than risk | The indications described in the publications may be followed; may be conventional or “first-line” therapy |

| B | Conclusive level 2 publications that demonstrate that benefit is greater than risk | The indications described in the publications may be followed. Monitor adverse effects; may be recommended as “second-line” therapy |

| C | Conclusive level 1, 2, 3 publications. No risk, no benefit | The indications described in the publications may be followed if the patient refuses or does not respond to conventional therapy. No objection to recommend use |

| D | Non-conclusive level 1, 2, 3, publications. Conclusive level 1, 2, 3 publications showing that risk is greater than benefit | Not recommended |

Source: Rindfleisch et al.7

None.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Franco Ruiz S, González Maldonado P. Los suplementos dietéticos y el anestesiólogo: resultados de investigación y estado del arte. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2014;42:90–99.