Patient preparation for surgery and transfer to the operating room are two priority processes defined within the procedures and conditions for authorization of health care services by the Ministry of Social Protection in Colombia.

ObjectivesThe aim of this initiative was to develop a manual of clinical management based on the evidence on patient preparation for surgery and transfer to the operating room.

Materials and methodsA process divided into four phases (conformation of the development group, systematic review of secondary literature, participatory consensus method, and preparation and writing of the final document) was performed. Each of the standardized techniques and procedures is used to develop evidence-based manuals.

ResultsEvidence-based recommendations on pre-anaesthetic assessment, preoperative management of medical conditions, education and patient communication, informed consent, patient transfer to the surgical area, surgical site marking, strategies for infection prevention and checklist were performed.

ConclusionIt is expected that with the use of this manual the incidence of events that produce morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing surgical procedures will be minimized.

La preparación del paciente para el acto quirúrgico y el traslado del paciente al quirófano son 2 procesos prioritarios definidos dentro de los procedimientos y condiciones de habilitación de servicios de salud por parte del Ministerio de Salud y la Protección Social en Colombia.

ObjetivosEl objetivo de esta iniciativa fue desarrollar un manual de manejo clínico basado en la evidencia sobre la preparación del paciente para el acto quirúrgico y traslado al quirófano.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un proceso dividido en 4 fases (conformación del grupo elaborador, revisión sistemática de literatura secundaria, método participativo de consenso, y preparación y escritura del documento final). Cada una de ellas usó técnicas y procedimientos estandarizados para el desarrollo de manuales basados en la evidencia.

ResultadosSe realizaron recomendaciones basadas en la evidencia sobre valoración preanestésica, manejo preoperatorio de condiciones médicas, educación y comunicación con los pacientes, consentimiento informado, traslado del paciente al área quirúrgica, marcación del sitio quirúrgico, estrategias para la prevención de infecciones, y lista de chequeo preoperatorio.

ConclusionesSe espera que con el uso de este manual se minimice la incidencia de eventos que produzcan morbimortalidad en pacientes sometidos a procedimientos quirúrgicos.

Protocols are crucial in clinical practice, in particular for ensuring safety in patient care, because their adoption minimizes variation in routine procedures, records, treatments and tasks. Protocols favour standardization and increase reliability of patient care, reducing human error while performing complex processes.1 The possibility of following protocols results in the ability to collect increasingly robust data, measure outcomes and indicators, and feed back into the processes. The recognition of critical processes in surgical patient care has led to the implementation of codes and effective communication techniques, and to a reduction of distractions and variations during their performance. This supports compliance, change and improvement actions to reduce life-threatening risks and to enhance patient wellbeing in the surgical setting. At present, patient safety is a field of study and research in all countries and has given rise to new knowledge and practices of undeniable benefit such as the well-known WHO Surgical Safety Checklist.2 Events regarding which there is more evidence available are the “never events”:

- •

performing a surgical procedure in the wrong patient

- •

performing the wrong procedure in a patient

- •

performing a procedure in the wrong surgical site

- •

leaving behind a foreign body after surgery3

There are others such as surgical site infection and hypothermia.

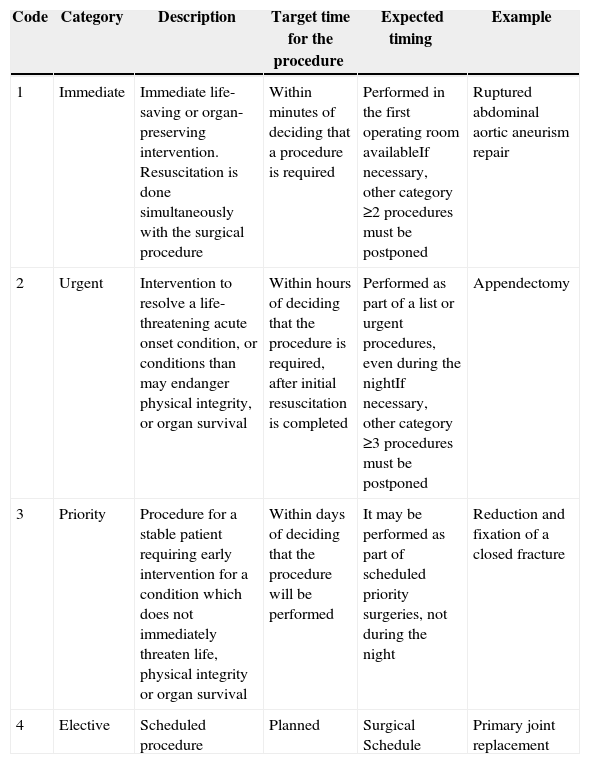

In Colombia, the Ministry of Health and Social Protection has established the procedure and conditions for healthcare service licensures and has defined priority processes that are prerequisites for the licensure of surgical services. Two of these processes are patient preparation for surgery and patient transfer to the operating theatre. This protocol delineates the mandatory steps that need to be consistently and systematically applied by a multidisciplinary team that is informed and committed to the care and wellbeing of the surgical patient.

Although the protocol must be applied before the surgical procedure (pre-operative period), its implementation requires anticipating diagnostic or therapeutic measures that might be required during surgery (intra-operative period) or after surgery (post-operative period). It is for this reason that the protocol refers in some instances to the perioperative period (pre-, intra- and post-operative).

The ultimate reason for applying this manual is to minimize the incidence of events leading to morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing anaesthetic procedures.

JustificationThe justification for this manual is compliance with the requirements of Resolution 2003 of the Ministry of Health, which defines the procedures and conditions for registration of Healthcare Institutions and for licensure of healthcare services. The Resolution mandates that a priority standardized procedure for all institutions providing surgical services at all levels of complexity, among others, is a protocol, manual or procedure for patient preparation for surgery and for the transfer of patients to the operating room.

The objective of this initiative was to develop an evidence-based clinical management manual for preparing patients for surgery, including the management of post-operative complications and post-operative follow-up.

MethodologyThe process consisted of four phases. Standardized procedures and techniques were used in all phases for developing evidence-based guidelines and protocols:

- •

Creation of the development team

- •

Systematic review of the secondary literature

- •

Participatory method

- •

Preparation and drafting of the final document

A group of experts in anaesthesiology and epidemiology was put together and entrusted with the job of establishing the methodological and technical guidelines within the framework of the development of the protocol. The group included two methodological coordinators with experience developing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines and management, whose job was to coordinate the methodology of the process. Three additional groups were also created, one consisting of an anaesthesia specialist and an epidemiologist with experience in critical analysis of scientific evidence. All of the members of the development team agreed to participate in the process and signed the disclosure document in accordance with the regulations governing the development of evidence-based guidelines and protocols.

Systematic review of the secondary literatureA systematic review of the literature was conducted in order to identify the clinical protocols and the clinical practice guidelines dealing with the topic of the protocol. The unit of analysis for the review consisted of the articles published in scientific journals or in technical documents found in the grey literature:

- •

Evidence-based management protocols (or, eventually, clinical practice guidelines) that included indications or recommendations related to the clinical management by the anaesthesiology group, pertaining to the topic of the protocol

- •

Published to date since 2011

- •

Published in English or Spanish

Literature searches were designed by the search coordinator of the Cochrane Sexually Transmitted Infections group. A sensitive digital search strategy (Annex 1) was designed in order to find the papers that met the criteria described above. The search continued until August 24th, 2014.

The sources of information were the databases of the biomedical scientific literature Medline, Embase and Lilacs, plus grey literature sources (Google Scholar).

Selection of the evidenceA database of the papers that would potentially meet the criteria mentioned above was created on the basis of the results of the search strategies. This database was given to reviewers who worked independently to read the titles and abstracts in order to identify the papers that met the requirements. In the event of disagreement, the two reviewers would settle it through the exchange of communications. The full texts of the selected documents were downloaded for final screening.

Quality evaluationThe AGREE II tool was used to evaluate the quality of the evidence found in the previous step (Annex 2). Quality was evaluated on the basis of a paired analysis.4

Finally, a protocol that met the eligibility requirements was identified and was used as the source document for the adaptation of the clinical management protocol to the context described above. The basis for identifying the source document included the clinical judgement of the experts, relevance, completeness of the indications (recommendations) and quality of the document.

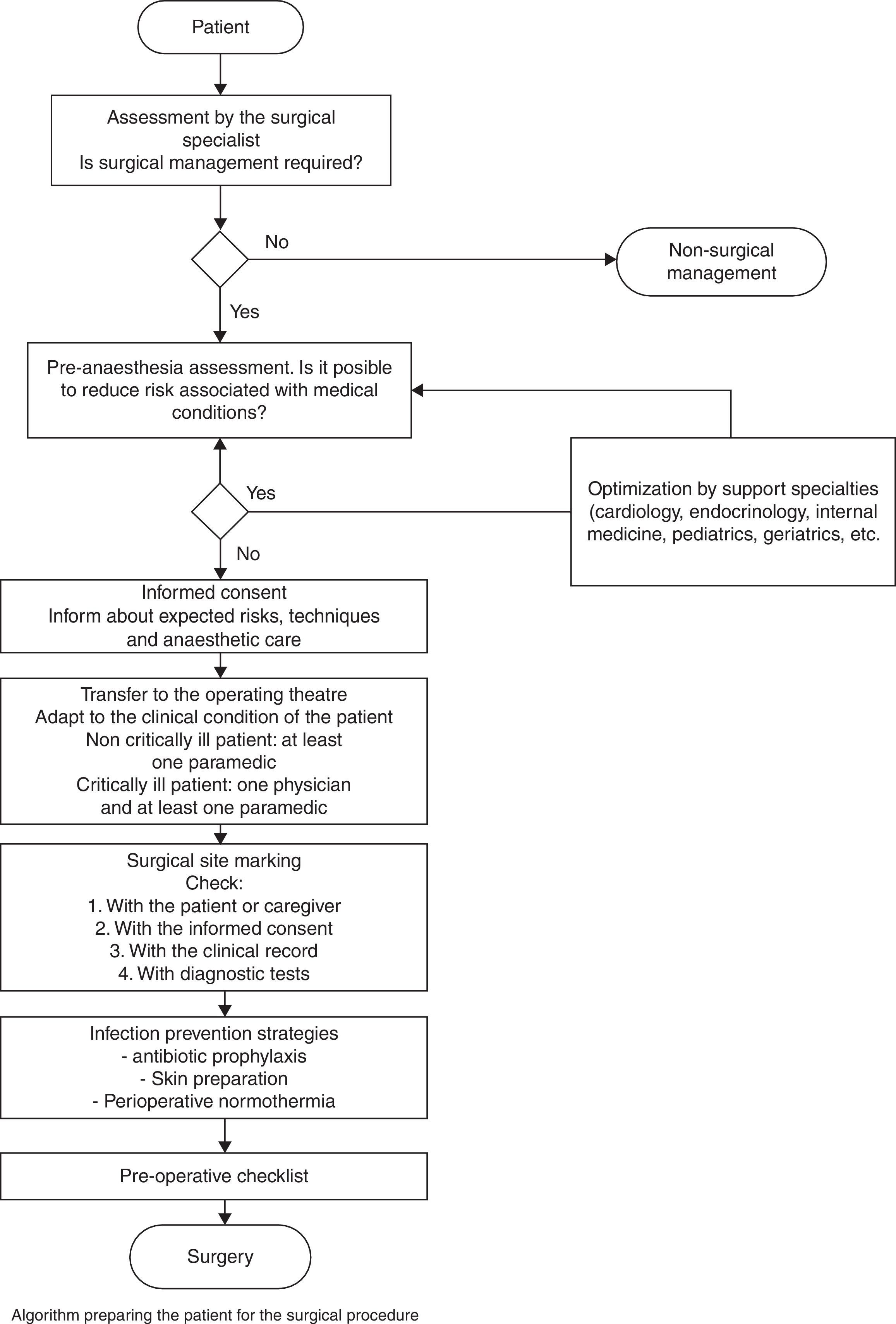

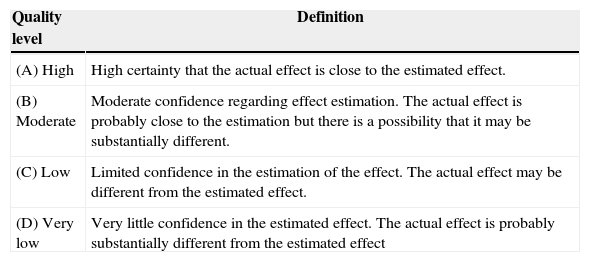

Rating of evidence quality and recommendation strengthGrade was used to inform the quality of the source evidence and the strength of the recommendation5,6 (Tables 1 and 2).

Evidence quality definitions.

| Quality level | Definition |

|---|---|

| (A) High | High certainty that the actual effect is close to the estimated effect. |

| (B) Moderate | Moderate confidence regarding effect estimation. The actual effect is probably close to the estimation but there is a possibility that it may be substantially different. |

| (C) Low | Limited confidence in the estimation of the effect. The actual effect may be different from the estimated effect. |

| (D) Very low | Very little confidence in the estimated effect. The actual effect is probably substantially different from the estimated effect |

Source: Definitions taken from Balshem et al.6

Recommendation strength definitions.

| Strength of the recommendation | Definition |

|---|---|

| (1) Strong | The desirable effects of following the recommendation are greater than the undesirable effects. Applicable to the majority of patients |

| (2) Weak | The desirable effects of following the recommendation may be greater than the undesirable effects. This balance may depend on local circumstances, values, and patients and anaesthetist preferences |

Source: Definitions taken from Card et al.7

A modified Delphi method was used. The development team chose the experts who would be asked to participate in the Delphi exercise. The meeting took place on September 18th at the S.C.A.R.E. premises, with the participation of 28 experts in anaesthesiology and epidemiology, and the following agenda:

- i.

Presentation of the project

- ii.

Methodology of the meeting

- iii.

Results of the evidence

- iv.

Clinical content of the manual

- v.

Vote

After presenting the clinical content of the manual, and following the discussion among the experts, agreement among them in relation to whether the protocol met the characteristics listed below was evaluated:

- •

Ease of implementation: Evaluates the possibility of the manual being readily used in the different institutions.

- •

Currency: Evaluates whether the indications are updated in relation to current evidence.

- •

Relevance: Evaluates whether the indications are relevant for the context of the majority of the surgical areas.

- •

Ethical considerations: Evaluates whether it is ethical to use this manual.

- •

Patient safety: Evaluates whether there is a high risk associated with the use of this protocol with patients.

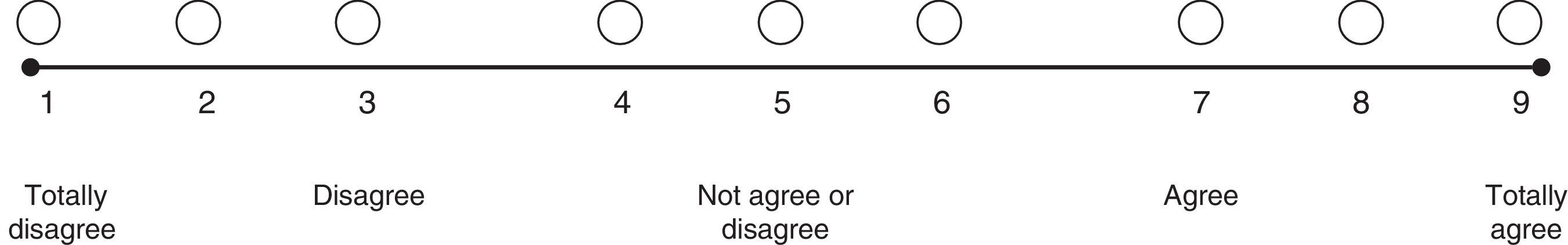

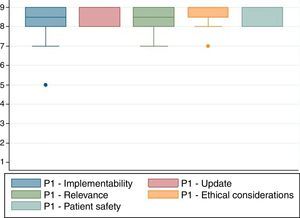

A nine-category ordinal scale was used for rating agreement in relation to each of the characteristics listed above (Fig. 1). Based on this, each of the proposed indications was rated as recommended (appropriate), contraindicated (inappropriate) or within a level of uncertainty. The rating was based on the Rand method (2004) cited by Sánchez Pedraza et al.8Fig. 2 shows the results of the agreement among the participants in the consensus meeting.

Rating scale in a formal consensus (real time Delphi).

Finally, a model protocol was structured to include the justification for preparing the document, the methodology used and the adaptation of the proposed document, on the basis of the recommendations of the experts during the participatory exercise. The final document was prepared by the development team.

Fig. 2 shows the results of the agreement among the participants in the consensus meeting.

Conflicts of interestAll the members of the development team and the participants in the expert consensus meeting completed and signed the disclosure form in accordance with the format and recommendation from the Cochrane group.

CopyrightPermission was obtained for the use and translation of the guidelines contained in this series of manuals. Translation and partial reproduction were authorized by Lippincott Williams and Wilkins/Wolters Kluwer Health, Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain & Ireland & the AAGBI Foundation, Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement.

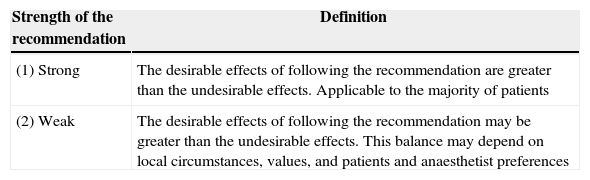

Clinical contentPreparing a patient for a surgical procedure requires of a series of sub-processes usually performed sequentially. This is how they should proceed because one process is a pre-requisite for the next. However, the whole sequence must be adjusted to the context of each patient, including the time interval between each of the stages, depending in particular on the type of intervention. The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death classification (NCEPOD)9 was adopted for this protocol (Table 3).

NCEPOD Intervention Classification.

| Code | Category | Description | Target time for the procedure | Expected timing | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Immediate | Immediate life-saving or organ-preserving intervention. Resuscitation is done simultaneously with the surgical procedure | Within minutes of deciding that a procedure is required | Performed in the first operating room availableIf necessary, other category ≥2 procedures must be postponed | Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurism repair |

| 2 | Urgent | Intervention to resolve a life-threatening acute onset condition, or conditions than may endanger physical integrity, or organ survival | Within hours of deciding that the procedure is required, after initial resuscitation is completed | Performed as part of a list or urgent procedures, even during the nightIf necessary, other category ≥3 procedures must be postponed | Appendectomy |

| 3 | Priority | Procedure for a stable patient requiring early intervention for a condition which does not immediately threaten life, physical integrity or organ survival | Within days of deciding that the procedure will be performed | It may be performed as part of scheduled priority surgeries, not during the night | Reduction and fixation of a closed fracture |

| 4 | Elective | Scheduled procedure | Planned | Surgical Schedule | Primary joint replacement |

Source: Taken from www.ncepod.org.uk9

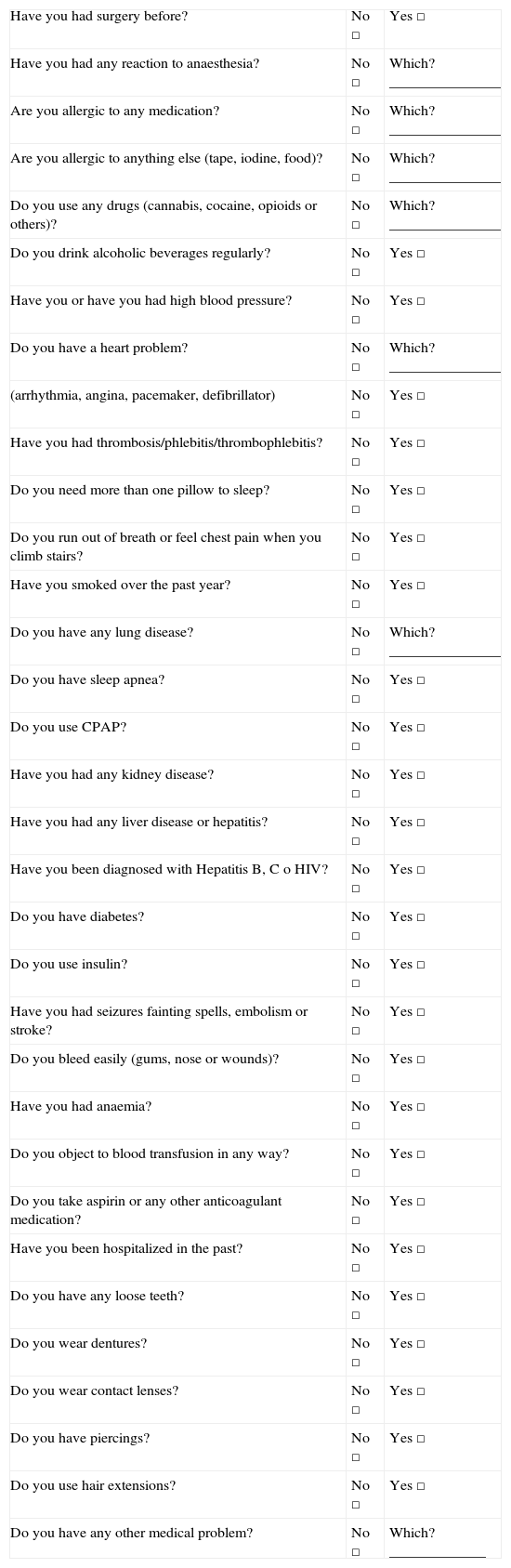

The medical history and the physical examination are the best strategies to identify pre-operative problems. The time devoted to the pre-anaesthesia assessment may be optimized through the use of questionnaires (Table 4). These are not meant to replace the assessment by the anaesthetist but rather to facilitate identification of important points, and to document patient responses.10

Recommended questionnaire for patients.

| Have you had surgery before? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you had any reaction to anaesthesia? | No □ | Which? _______________ |

| Are you allergic to any medication? | No □ | Which? _______________ |

| Are you allergic to anything else (tape, iodine, food)? | No □ | Which? _______________ |

| Do you use any drugs (cannabis, cocaine, opioids or others)? | No □ | Which? _______________ |

| Do you drink alcoholic beverages regularly? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you or have you had high blood pressure? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you have a heart problem? | No □ | Which? _______________ |

| (arrhythmia, angina, pacemaker, defibrillator) | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you had thrombosis/phlebitis/thrombophlebitis? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you need more than one pillow to sleep? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you run out of breath or feel chest pain when you climb stairs? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you smoked over the past year? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you have any lung disease? | No □ | Which? _______________ |

| Do you have sleep apnea? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you use CPAP? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you had any kidney disease? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you had any liver disease or hepatitis? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you been diagnosed with Hepatitis B, C o HIV? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you have diabetes? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you use insulin? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you had seizures fainting spells, embolism or stroke? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you bleed easily (gums, nose or wounds)? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you had anaemia? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you object to blood transfusion in any way? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you take aspirin or any other anticoagulant medication? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Have you been hospitalized in the past? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you have any loose teeth? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you wear dentures? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you wear contact lenses? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you have piercings? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you use hair extensions? | No □ | Yes □ |

| Do you have any other medical problem? | No □ | Which? _____________ |

Source: Adapted from Card et al.7

Ideally, the pre-anaesthesia assessment must be done at least one week before an elective surgical procedure in order to allow time to provide adequate patient education. It is worth noting that this time interval may be adjusted to suit the specific characteristics of the individual patient and the type of surgical procedure.7

Patients, family members or caregivers must be advised that the pre-anaesthesia assessment is no substitute for health promotion, disease prevention, or early detection programmes.

- •

All patients undergoing diagnostic or therapeutic procedures must have a pre-anaesthesia assessment, except patients with no severe systemic diseases who require topical or local anaesthesia [GRADE C1].

The pre-anaesthesia assessment must include at least the following:

- •

Elective procedure

- –

Reason for the surgical procedure

- –

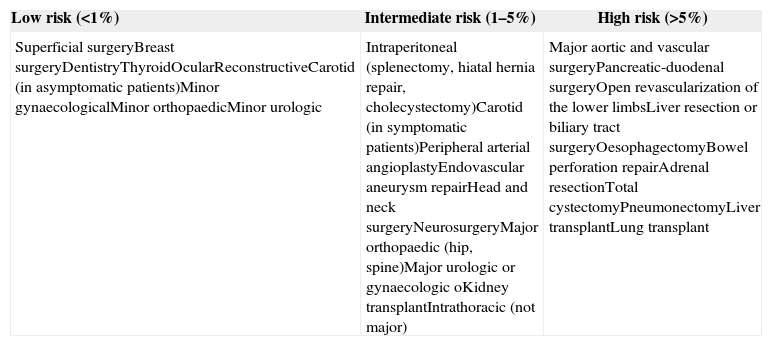

Estimated surgical risk (Table 5)11

Table 5.Estimated surgical risk according to the type of procedure or intervention.

Low risk (<1%) Intermediate risk (1–5%) High risk (>5%) Superficial surgeryBreast surgeryDentistryThyroidOcularReconstructiveCarotid (in asymptomatic patients)Minor gynaecologicalMinor orthopaedicMinor urologic Intraperitoneal (splenectomy, hiatal hernia repair, cholecystectomy)Carotid (in symptomatic patients)Peripheral arterial angioplastyEndovascular aneurysm repairHead and neck surgeryNeurosurgeryMajor orthopaedic (hip, spine)Major urologic or gynaecologic oKidney transplantIntrathoracic (not major) Major aortic and vascular surgeryPancreatic-duodenal surgeryOpen revascularization of the lower limbsLiver resection or biliary tract surgeryOesophagectomyBowel perforation repairAdrenal resectionTotal cystectomyPneumonectomyLiver transplantLung transplant Source: Surgical risk estimation is an approach to the 30-day risk of cardiovascular death and infarction that only takes into consideration the specific surgical intervention and attaches less importance to patient comorbidities.11

- –

- •

Medical history

- –

Surgical history and complications

- –

Anaesthesia history and complications

- –

Allergies and intolerance to medications and other substances (specifying the type of reaction)

- –

Medication use (prescription, over-the-counter, herbal, nutritional, etc.)

- –

Disease history

- –

Nutritional status

- –

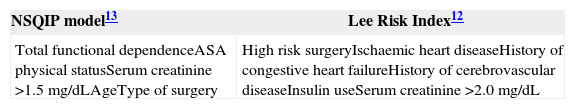

Cardiovascular status (Table 6)12,13

Table 6.Factors used for stratifying cardiovascular risk.

NSQIP model13 Lee Risk Index12 Total functional dependenceASA physical statusSerum creatinine >1.5mg/dLAgeType of surgery High risk surgeryIschaemic heart diseaseHistory of congestive heart failureHistory of cerebrovascular diseaseInsulin useSerum creatinine >2.0mg/dL Source: Taken from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP).7

- –

Pulmonary status

- –

Functional class14–16

- –

Haemostatic status (personal and family history of abnormal bleeding)

- –

Possibility of symptomatic anaemia

- –

Possibility of pregnancy (women in childbearing age)

- –

Personal and family history of anaesthetic complications

- –

Cigarette smoking, use of alcohol and other substances

- –

Identification of risk factors for surgical site infection (cigarette smoking,

- –

Diabetes, obesity, malnutrition, chronic skin diseases)

- –

- •

Physical examination

- –

Weight, height and body mass index

- –

Vital signs: blood pressure, pulse (rate and regularity), respiratory rate

- –

Heart

- –

Lung

- –

Difficult airway probability

- –

Risk models should not dictate management decisions, but they must be considered as one of the many pieces in the puzzle, and must be assessed together with the traditional information available to the practitioner.17

Pre-operative diagnostic tests. The paradigm regarding orders for diagnostic tests has changed in the whole world over the last few decades.18 Diagnostic tests not supported by the findings of the medical history or the physical examination are not cost-effective, do not grant medico-legal protection and might be deleterious for the patient.19–21 Discussing the indications for ordering the long list of diagnostic tests available to clinical practice is beyond the scope of this protocol.

For patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery, the recommendation is to order diagnostic tests for cardiovascular assessment in accordance with any of the current international guidelines.17,22

Electrocardiogram- •

Ordering a pre-operative electrocardiogram may be considered in patients 65 or over during the previous year before the surgical procedure [GRADE C2].

- •

A pre-operative electrocardiogram is not recommended in patients undergoing other low risk procedures, unless the medical history or the physical examination reveals that the patient is high risk [GRADE A1].

- •

An electrocardiogram is not indicated – regardless of age – in patients who will be taken to cataract surgery [GRADE A1].

- •

A pre-operative whole blood count must be ordered on the basis of findings of the medical history and the physical examination, and the potential blood loss of the elective procedure [GRADE C1].

- •

They are recommended in patients on chronic use of digoxin, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists (ARAs) [GRADE D2].

- •

A chest X-ray must be obtained (AP and lateral views) in patients with signs or symptoms suggesting undiagnosed or chronic unstable cardiopulmonary disease [GRADE D2].

- •

It must be obtained in women in childbearing age who may be pregnant given a menstrual delay or given the explicit suspicion of pregnancy by the patient, or because of an uncertain pregnancy possibility (e.g. irregular menstruation) [GRADE C1].

- •

The presence of risk factors for perioperative cardiovascular complications must be assessed in all patients17 [GRADE A1].

- •

Therapy with beta-blockers must be continued during the perioperative period in patients with a history of permanent use of this type of medications [GRADE A1].

- •

The use of beta-blockers must be considered in patients with a high risk of cardiac complications (Table 5) undergoing vascular surgery [GRADE C2].

- •

The use of beta-blockers must be considered in patients with coronary heart disease or high cardiac risk (two or more risk factors) undergoing a surgical procedure of intermediate cardiovascular risk (Tables 5 and 6) [GRADE C2].

- •

Therapy with beta blockers must be started one to two weeks before surgery and the dose must be titrated in order to achieve a heart rate between 60 and 80 beats per minute [GRADE A1].

- •

Patients with permanent use of statins must continue to use them during the perioperative period [GRADE 1].

- •

The use of perioperative statin therapy must be considered in patients undergoing vascular or intermediate risk surgery [GRADE C2].

- •

In cases where the medical history suggests potential coagulation problems, coagulation tests must be obtained [GRADE C1].

- •

Surgery must be avoided for at least six weeks after the placement of a metal stent [GRADE C1].

- •

Surgery must be delayed for at least one year after the placement of a drug-eluting stent [GRADE C1].

- •

In the event it is not possible to postpone the surgery during the recommended time periods, dual anti-platelet aggregation therapy must be continued during the perioperative period unless it is contraindicated (surgery with a high risk of bleeding, intracranial surgery, etc.) [GRADE C1].

- •

In the event the interruption of clopidogrel/prasugrel/ticlopidine is considered necessary before the procedure, aspirin must be continued during the perioperative period – if possible – in order to reduce cardiac risk [GRADE C1].

- •

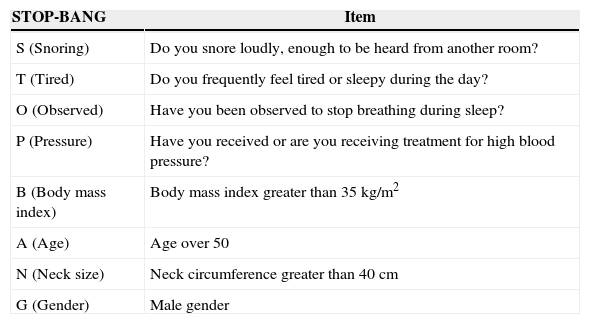

The potential for sleep apnea in patients (Table 7) must be assessed and the results must be communicated to the surgical team [GRADE C1].

Table 7.Pre-operative detection of patients with sleep apnea.

STOP-BANG Item S (Snoring) Do you snore loudly, enough to be heard from another room? T (Tired) Do you frequently feel tired or sleepy during the day? O (Observed) Have you been observed to stop breathing during sleep? P (Pressure) Have you received or are you receiving treatment for high blood pressure? B (Body mass index) Body mass index greater than 35kg/m2 A (Age) Age over 50 N (Neck size) Neck circumference greater than 40cm G (Gender) Male gender Low risk (0–2 points), high risk (≥3 points).

Source: Taken from Chung et al.23,24

- •

Patients diagnosed with sleep apnea who receive positive airway pressure treatment (CPAP) must bring their device for use during the immediate post-operative period [GRADE B2].

- •

Blood sugar control must be targeted to achieve glycaemic concentration levels of 140–180mg/dL and not to achieve more stringent targets (e.g. 80–110mg/dL) [GRADE A1].

- •

Individualized assessment is required in order to issue instructions designed to avoid extreme glycaemic changes [GRADE C1].

- •

Long-acting insulin dose (glargine, NPH, etc.) must be reduced by 50% during the pre-operative period [GRADE C1].

- •

Oral anti-diabetic medications and short-acting insulins should not be used before the surgical procedure [GRADE C1].

- •

Sliding scale insulin regimens during the perioperative period must be used for treating hyperglycaemia in patients with difficult-to-manage diabetes mellitus [GRADE C1].

- •

GLP-1 agonists (exenatide, liraglutide, pramlintide) must be interrupted during the perioperative period [GRADE C1].

- •

DPP-4 inhibitors (sitagliptin) may continue to be used during the perioperative period [GRADE C2].

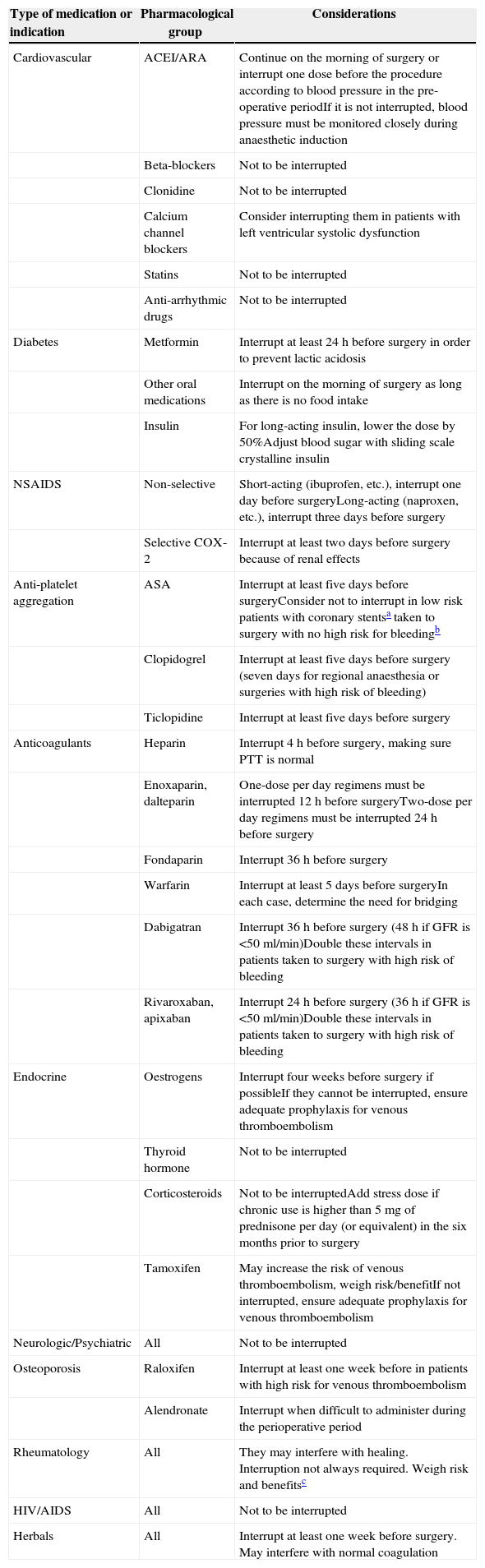

Table 9.Pre-operative estimation of the risk for venous thromboembolism.

Risk factor Points Age ≥60 years 1 Body mass index ≥40kg/m2 1 Male gender 2 SIRS/sepsis/septic shock 3 Personal history of venous thromboembolism 3 Family history of venous thromboembolism 4 On-going cancer 5 Minimum risk (0 points), low risk (1–2 points), moderate risk (3–5 points), high risk (≥6 points).

Source: Taken from Pannucci et al.28

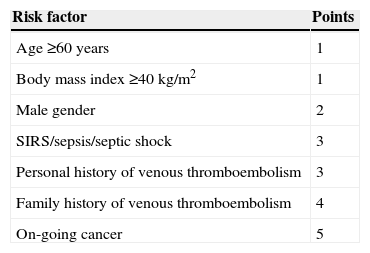

- •

A thorough determination of medication use by the patient is required (prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, herbal products and nutritional supplements) at least one week before an elective surgical procedure [GRADE C1].

Table 8.Pre-operative management of chronic-use medications.

Type of medication or indication Pharmacological group Considerations Cardiovascular ACEI/ARA Continue on the morning of surgery or interrupt one dose before the procedure according to blood pressure in the pre-operative periodIf it is not interrupted, blood pressure must be monitored closely during anaesthetic induction Beta-blockers Not to be interrupted Clonidine Not to be interrupted Calcium channel blockers Consider interrupting them in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction Statins Not to be interrupted Anti-arrhythmic drugs Not to be interrupted Diabetes Metformin Interrupt at least 24h before surgery in order to prevent lactic acidosis Other oral medications Interrupt on the morning of surgery as long as there is no food intake Insulin For long-acting insulin, lower the dose by 50%Adjust blood sugar with sliding scale crystalline insulin NSAIDS Non-selective Short-acting (ibuprofen, etc.), interrupt one day before surgeryLong-acting (naproxen, etc.), interrupt three days before surgery Selective COX-2 Interrupt at least two days before surgery because of renal effects Anti-platelet aggregation ASA Interrupt at least five days before surgeryConsider not to interrupt in low risk patients with coronary stentsa taken to surgery with no high risk for bleedingb Clopidogrel Interrupt at least five days before surgery (seven days for regional anaesthesia or surgeries with high risk of bleeding) Ticlopidine Interrupt at least five days before surgery Anticoagulants Heparin Interrupt 4h before surgery, making sure PTT is normal Enoxaparin, dalteparin One-dose per day regimens must be interrupted 12h before surgeryTwo-dose per day regimens must be interrupted 24h before surgery Fondaparin Interrupt 36h before surgery Warfarin Interrupt at least 5 days before surgeryIn each case, determine the need for bridging Dabigatran Interrupt 36h before surgery (48h if GFR is <50ml/min)Double these intervals in patients taken to surgery with high risk of bleeding Rivaroxaban, apixaban Interrupt 24h before surgery (36h if GFR is <50ml/min)Double these intervals in patients taken to surgery with high risk of bleeding Endocrine Oestrogens Interrupt four weeks before surgery if possibleIf they cannot be interrupted, ensure adequate prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism Thyroid hormone Not to be interrupted Corticosteroids Not to be interruptedAdd stress dose if chronic use is higher than 5mg of prednisone per day (or equivalent) in the six months prior to surgery Tamoxifen May increase the risk of venous thromboembolism, weigh risk/benefitIf not interrupted, ensure adequate prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism Neurologic/Psychiatric All Not to be interrupted Osteoporosis Raloxifen Interrupt at least one week before in patients with high risk for venous thromboembolism Alendronate Interrupt when difficult to administer during the perioperative period Rheumatology All They may interfere with healing. Interruption not always required. Weigh risk and benefitsc HIV/AIDS All Not to be interrupted Herbals All Interrupt at least one week before surgery. May interfere with normal coagulation aHigh risk stent: Metal stents implanted less than six weeks before, or drug-eluting stents implanted less than one year before.

bHigh risk of bleeding: blood loss of more than 15ml/kg or involving the brain, retina, spinal cord or nerve trunks; neuroaxial anaesthesia must be considered for this group.25

cIf interruption is decided, allow for a pre-operative interval equal to four or five half lives of the medication. E.g. hydroxychloroquine (four months), etanercept (two weeks), infliximab/adalimumab (four weeks), rituximab (six months), abatacept (two months).26,27

- •

In general, medications that contribute to homeostasis must be continued during the perioperative period, except for those that may increase the probability of adverse events (NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors/ARAs, insulin and blood sugar lowering drugs, anticoagulants, biological, medications for osteoporosis, hormonal therapy, etc.) [GRADE C1].

In general, all medications that do not contribute to maintaining homeostasis must be interrupted (non-prescription drugs, herbal or natural products, nutritional supplements, etc.) [GRADE C1].

Smoking cessation- •

Patients must be encouraged to stop smoking [GRADE C1].

- •

All patients must be assessed for the perioperative risk of venous thromboembolism, and the quantification must be documented in the clinical record. It is recommended to discuss the appropriate measures for preventing thromboembolic complications with other members of the surgical team.28

Recommendations on pre-operative fasting (NPO) have been revised and simplified considerably over the past decade. Management guidelines have been published establishing the “2, 4, 6, 8 hour rule”, which is applied to patients of all ages.29,30

Patients must be educated and informed of the fasting requirements with sufficient time in advance.

- •

The recommended fasting period for clear liquids such as water, fruit juices with no pulp, carbonated drinks, clear tea and coffee is 2h or more before the surgical procedure [GRADE B1].

- •

The recommended fasting period for breast milk is 4h or more before the surgical procedure [GRADE B1].

- •

The recommended fasting period for milk formula, non-human milk and light meals (such as toast) is 6h or more before the surgical procedure [GRADE B1].

- •

The fasting period for fried or fat food, or meat, must be 8h or more, because these foods may prolong gastric emptying [GRADE B1].

In order to prevent infections, patients must be encouraged to bathe on the day of the surgical procedure. They must be told not to shave or remove any hair at, or close to, the surgical site. Every institution must establish specific guidelines for its patient population and the specific surgical procedures they perform (see Skin Preparation).

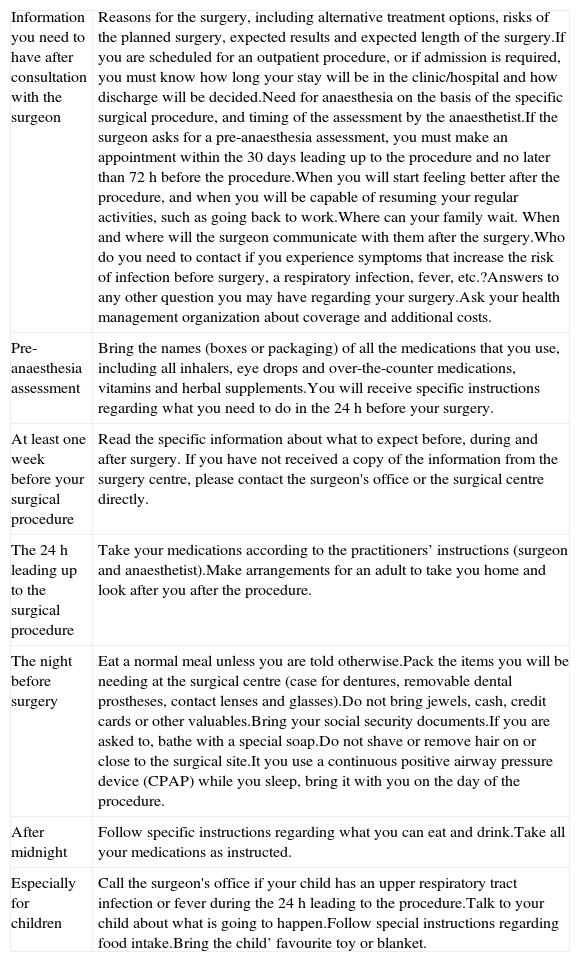

Communication with patients and caregiversA reliable mechanism must be established for communicating the result of the pre-anaesthesia assessment, including the results of diagnostic tests and instructions for surgical site marking, aside from patient identification before the procedure (Table 10).7

- •

In cases of elective procedures, it is recommended to provide patients or caregivers with printed material with the most relevant instructions for preparing for the surgical procedure [GRADE D2].

Pre-operative guidelines for patients and caregivers.

| Information you need to have after consultation with the surgeon | Reasons for the surgery, including alternative treatment options, risks of the planned surgery, expected results and expected length of the surgery.If you are scheduled for an outpatient procedure, or if admission is required, you must know how long your stay will be in the clinic/hospital and how discharge will be decided.Need for anaesthesia on the basis of the specific surgical procedure, and timing of the assessment by the anaesthetist.If the surgeon asks for a pre-anaesthesia assessment, you must make an appointment within the 30 days leading up to the procedure and no later than 72h before the procedure.When you will start feeling better after the procedure, and when you will be capable of resuming your regular activities, such as going back to work.Where can your family wait. When and where will the surgeon communicate with them after the surgery.Who do you need to contact if you experience symptoms that increase the risk of infection before surgery, a respiratory infection, fever, etc.?Answers to any other question you may have regarding your surgery.Ask your health management organization about coverage and additional costs. |

| Pre-anaesthesia assessment | Bring the names (boxes or packaging) of all the medications that you use, including all inhalers, eye drops and over-the-counter medications, vitamins and herbal supplements.You will receive specific instructions regarding what you need to do in the 24h before your surgery. |

| At least one week before your surgical procedure | Read the specific information about what to expect before, during and after surgery. If you have not received a copy of the information from the surgery centre, please contact the surgeon's office or the surgical centre directly. |

| The 24h leading up to the surgical procedure | Take your medications according to the practitioners’ instructions (surgeon and anaesthetist).Make arrangements for an adult to take you home and look after you after the procedure. |

| The night before surgery | Eat a normal meal unless you are told otherwise.Pack the items you will be needing at the surgical centre (case for dentures, removable dental prostheses, contact lenses and glasses).Do not bring jewels, cash, credit cards or other valuables.Bring your social security documents.If you are asked to, bathe with a special soap.Do not shave or remove hair on or close to the surgical site.It you use a continuous positive airway pressure device (CPAP) while you sleep, bring it with you on the day of the procedure. |

| After midnight | Follow specific instructions regarding what you can eat and drink.Take all your medications as instructed. |

| Especially for children | Call the surgeon's office if your child has an upper respiratory tract infection or fever during the 24h leading to the procedure.Talk to your child about what is going to happen.Follow special instructions regarding food intake.Bring the child’ favourite toy or blanket. |

Source: Adapted from Card et al.7

Despite the unique challenges of obtaining the informed consent for anaesthetic procedures, patients, parents or caregivers must be informed of the general and specific anaesthetic risks, and about anaesthetic care. Strategies to improve understanding of the information must be implemented in order to ensure that decision-makers are adequately informed.31,32

- •

The anaesthesia informed consent must be given to all patients (signed by the patient, parents or caregivers) who are taken to diagnostic or therapeutic procedures [GRADE A1].

Patients must be transferred to the operating room in a manner consistent with their clinical condition. Transfer implies that patients require care in different areas of the health facilities and, consequently, there is a need for patient handover and reception processes. There is a generalized consensus at present in the sense that robust and structured handover processes are critical for safe patient care. The use of checklists and software tools to facilitate the transfer process may improve reliability and help eliminate stress for the healthcare staff. Transfer and handover processes must be adapted to every specific clinical setting.33

In view of the above, there are two groups of patients that require specific considerations:

- •

Outpatients and non-critically ill inpatients.

- –

In order to prevent injuries from falls, patients cannot ambulate during transfer. They must be transferred in a wheel chair or trolley.

- –

Devices to ensure safe transfer must be available in accordance with the specific needs of the individual patient (e.g. oxygen, infusion pumps, etc.).

- –

At least one paramedic must participate in transfers.

- –

- •

Critically ill patients. Aside from the above,

- –

Transfer with monitoring, at least non-invasive blood pressure, continuous electrocardiogram and pulse oxymetry

- –

Invasive ventilation support devices must be available in accordance with the clinical indications, with the possibility of giving positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

- –

The leader of the transfer group must be a physician, supported by paramedical staff.

- –

- •

Patient transfers to the operating theatre must be adapted to the individual clinical conditions of the patient (critically ill or non-critically ill). The handover and reception process must be documented in the clinical record [GRADE C1].

A wrong surgery may be the result of misinformation of the surgical team or misperception of patient orientation. The key to prevent such an event is to have multiple independent information checkpoints. Inconsistencies between the pre-anaesthesia assessment, the informed consent and the surgeon's notes in relation to the medical history and the physical examination must be addressed, ideally, before the start of any pre-operative procedure.34 Before marking the surgical site, patient identification and the correct site for the surgical procedure must be checked as follows:

- –

Information contained in the informed consent

- –

Information contained in the clinical record

- –

Diagnostic tests

- –

Interview with the patient, parent or caregiver [GRADE A1]

Post-operative infection is a serious complication. It is the most frequent source of in-hospital morbidity for patients undergoing surgical procedures, and it is associated with increased length of hospital stay, a higher risk of mortality and lower quality of life.35,36

It may happen as a result of the surgical procedure and also as a result of anaesthetic procedures. Several strategies have been described to diminish the risk of post-operative infection from the point of view of the anaesthetist: They include, among others

- •

Prophylactic antibiotics

- •

Perioperative normothermia

- •

Adequate skin preparation37-39

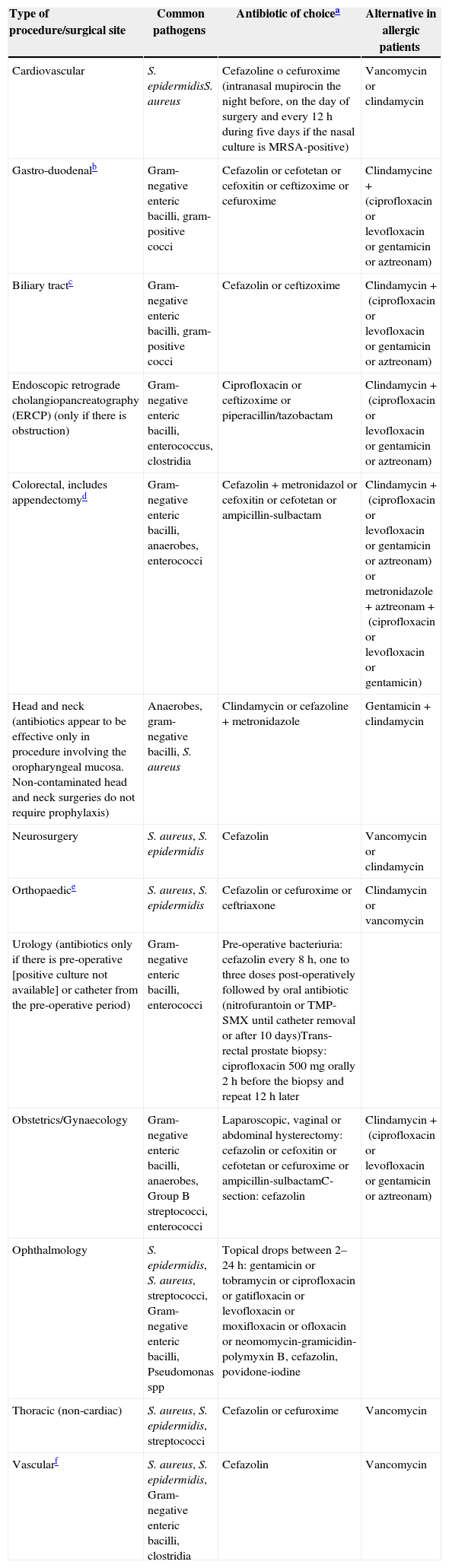

The pre-operative use of prophylactic antibiotics has been shown to reduce the risk of post-operative surgical site infection. Recommendations have been published on the type of antibiotics (Table 11) and their dosing (Table 12) for use as pre-operative prophylaxis in accordance with the type of surgical procedure.40 Pre-operative antibiotics must be given with the goal of achieving bactericidal tissue concentrations at the time of the incision. For most antibiotics, this concentration is achieved 30min after administration. Vancomycin and fluoroquinolones must be given within the 120min leading to the procedure because they require longer infusion times.40 In those cases in which antibiotics cannot be given within the recommended time intervals (e.g. in a child without vascular access), they must be given as soon as the impediment is resolved. Late administration of antibiotic prophylaxis does not reduce its effectiveness.41

- •

All patients must be assessed for known medication allergies [GRADE C1].

- •

An adequate prophylactic antibiotic must be given, depending on the type of surgery, between 30min and 2h before the start of the procedure. This time interval will depend on the antibiotic used [GRADE C1].

- •

Prophylactic antibiotics, in non-cardiac surgery, must be interrupted within 24h after the end of the procedure [GRADE C1].

- •

Prophylactic antibiotics, in cardiac surgery, must be interrupted within 48h after the end of the procedure [GRADE C1].

Recommendations for pre-operative prophylactic antibiotics.

| Type of procedure/surgical site | Common pathogens | Antibiotic of choicea | Alternative in allergic patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | S. epidermidisS. aureus | Cefazoline o cefuroxime (intranasal mupirocin the night before, on the day of surgery and every 12h during five days if the nasal culture is MRSA-positive) | Vancomycin or clindamycin |

| Gastro-duodenalb | Gram-negative enteric bacilli, gram-positive cocci | Cefazolin or cefotetan or cefoxitin or ceftizoxime or cefuroxime | Clindamycine+(ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin or gentamicin or aztreonam) |

| Biliary tractc | Gram-negative enteric bacilli, gram-positive cocci | Cefazolin or ceftizoxime | Clindamycin+(ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin or gentamicin or aztreonam) |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (only if there is obstruction) | Gram-negative enteric bacilli, enterococcus, clostridia | Ciprofloxacin or ceftizoxime or piperacillin/tazobactam | Clindamycin+(ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin or gentamicin or aztreonam) |

| Colorectal, includes appendectomyd | Gram-negative enteric bacilli, anaerobes, enterococci | Cefazolin+metronidazol or cefoxitin or cefotetan or ampicillin-sulbactam | Clindamycin+(ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin or gentamicin or aztreonam) or metronidazole+aztreonam+(ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin or gentamicin) |

| Head and neck (antibiotics appear to be effective only in procedure involving the oropharyngeal mucosa. Non-contaminated head and neck surgeries do not require prophylaxis) | Anaerobes, gram-negative bacilli, S. aureus | Clindamycin or cefazoline+metronidazole | Gentamicin+clindamycin |

| Neurosurgery | S. aureus, S. epidermidis | Cefazolin | Vancomycin or clindamycin |

| Orthopaedice | S. aureus, S. epidermidis | Cefazolin or cefuroxime or ceftriaxone | Clindamycin or vancomycin |

| Urology (antibiotics only if there is pre-operative [positive culture not available] or catheter from the pre-operative period) | Gram-negative enteric bacilli, enterococci | Pre-operative bacteriuria: cefazolin every 8h, one to three doses post-operatively followed by oral antibiotic (nitrofurantoin or TMP-SMX until catheter removal or after 10 days)Trans-rectal prostate biopsy: ciprofloxacin 500mg orally 2h before the biopsy and repeat 12h later | |

| Obstetrics/Gynaecology | Gram-negative enteric bacilli, anaerobes, Group B streptococci, enterococci | Laparoscopic, vaginal or abdominal hysterectomy: cefazolin or cefoxitin or cefotetan or cefuroxime or ampicillin-sulbactamC-section: cefazolin | Clindamycin+(ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin or gentamicin or aztreonam) |

| Ophthalmology | S. epidermidis, S. aureus, streptococci, Gram-negative enteric bacilli, Pseudomonas spp | Topical drops between 2–24h: gentamicin or tobramycin or ciprofloxacin or gatifloxacin or levofloxacin or moxifloxacin or ofloxacin or neomomycin-gramicidin-polymyxin B, cefazolin, povidone-iodine | |

| Thoracic (non-cardiac) | S. aureus, S. epidermidis, streptococci | Cefazolin or cefuroxime | Vancomycin |

| Vascularf | S. aureus, S. epidermidis, Gram-negative enteric bacilli, clostridia | Cefazolin | Vancomycin |

The administration of repeated antibiotic doses for the prevention of surgical site infection depends on the type of antibiotic selected and the length of the surgical procedure. Single antibiotic doses are recommended only for procedures lasting less than 4h. In procedures lasting more than 4h, or when blood loss is greater than 70ml/kg the repeat dose may be given every one or two half-lives (in patients with normal renal function) in order to maintain bactericidal tissue concentrations while tissues remain exposed.42-44

Only for patients with a high risk of infection: oesophageal obstruction, morbid obesity, reduction of gastric acid or gastric motility (due to obstruction, haemorrhage, gastric ulcer, cancer, or treatment with proton pump inhibitors). Not indicated for routine gastro-oesophageal endoscopy.

Only for patients with a high risk of infection: older than 70, acute cholecystitis, non-functional gallbladder, obstructive jaundice. Cholangitis must be treated as an infection and not with prophylaxis.

The use of bowel preparation with oral antibiotics one day before surgery is controversial and must be used at the surgeon's discretion.45-47

If a tourniquet is used during the procedure, the entire antibiotic dose must be given before it is inflated.

A single dose of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid reduces wound site infections in the groin after varicose vein surgery, and must be considered for this type of procedure.48

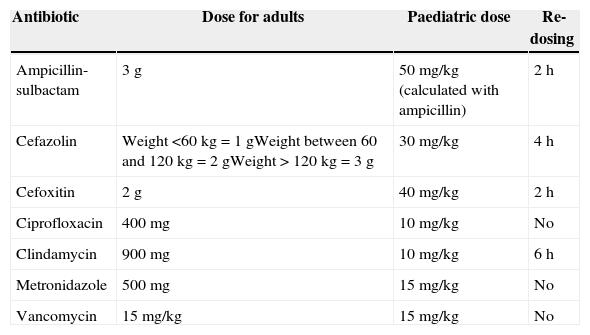

Recommended doses for prophylactic antibiotics.

| Antibiotic | Dose for adults | Paediatric dose | Re-dosing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | 3g | 50mg/kg (calculated with ampicillin) | 2h |

| Cefazolin | Weight <60kg=1gWeight between 60 and 120kg=2gWeight > 120kg=3g | 30mg/kg | 4h |

| Cefoxitin | 2g | 40mg/kg | 2h |

| Ciprofloxacin | 400mg | 10mg/kg | No |

| Clindamycin | 900mg | 10mg/kg | 6h |

| Metronidazole | 500mg | 15mg/kg | No |

| Vancomycin | 15mg/kg | 15mg/kg | No |

Source: Adapted from Bratzler et al.40

- •

Patients with a diagnosis of cardiac valve disease undergoing surgical procedures must receive adequate antibiotic prophylaxis [GRADE C1].

Procedures in patients with a history of joint replacement

- •

Patients with joint prostheses must not receive prophylactic antibiotics for the prevention of prosthesis-associated infection [GRADE C1].

Bowel preparation in colorectal surgery

- •

The use of mechanical bowel preparation is not recommended for reducing the post-operative risk of surgical site infection [GRADE A1].

- •

At the time of surgery, all patients must receive a prophylactic dose of effective antibiotics against colon and skin flora [GRADE A1].

Temperature must be monitored in all patients receiving anaesthesia and who are expected to undergo changes in central temperature49,50 SMD. There are many means and sites for measuring central temperature with different levels of accuracy and ease of use (oral, tympanic, oesophageal, axillary, skin, bladder, rectal, tracheal, nasopharyngeal, pulmonary artery catheter). The selection of the site depends on the access and the type of surgery.51

- •

Strategies must be put in place in order to reduce the risk of intra-operative hypothermia and associated complications (surgical site infection, cardiac complications, increased bleeding, etc.) [GRADE A1].

Most surgical site infections are caused by normal skin flora. The surgical site must be assessed before skin preparation.

The skin must be assessed for the presence of:

- •

nevi

- •

warts

- •

rash

- •

other skin conditions

Inadvertent lesion elimination may create the opportunity for wound colonization.52 Recommendations for skin preparation must be applied for anaesthetic procedures as well as for insertion of central vascular accesses.53

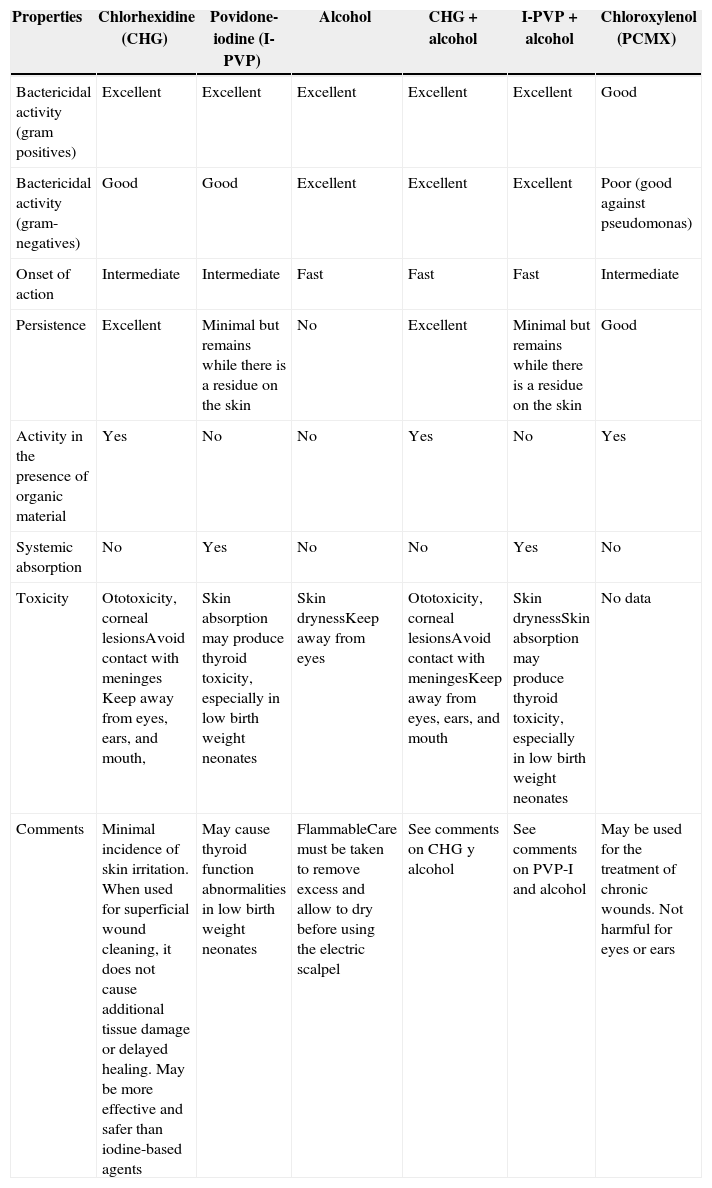

Application of antiseptic solutionsThere are several antiseptic agents available for pre-operative skin preparation of the incision site (Table 13), but there is limited evidence to recommend the use of one antiseptic agent over another.54 Selecting the ideal agent according to each group of patients requires careful consideration. Some antiseptic agents may injure mucosal tissue and others are highly flammable.

Comparison of some antiseptic solutions for clinical use.

| Properties | Chlorhexidine (CHG) | Povidone-iodine (I-PVP) | Alcohol | CHG+alcohol | I-PVP+alcohol | Chloroxylenol (PCMX) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bactericidal activity (gram positives) | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Good |

| Bactericidal activity (gram-negatives) | Good | Good | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Poor (good against pseudomonas) |

| Onset of action | Intermediate | Intermediate | Fast | Fast | Fast | Intermediate |

| Persistence | Excellent | Minimal but remains while there is a residue on the skin | No | Excellent | Minimal but remains while there is a residue on the skin | Good |

| Activity in the presence of organic material | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Systemic absorption | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Toxicity | Ototoxicity, corneal lesionsAvoid contact with meninges Keep away from eyes, ears, and mouth, | Skin absorption may produce thyroid toxicity, especially in low birth weight neonates | Skin drynessKeep away from eyes | Ototoxicity, corneal lesionsAvoid contact with meningesKeep away from eyes, ears, and mouth | Skin drynessSkin absorption may produce thyroid toxicity, especially in low birth weight neonates | No data |

| Comments | Minimal incidence of skin irritation. When used for superficial wound cleaning, it does not cause additional tissue damage or delayed healing. May be more effective and safer than iodine-based agents | May cause thyroid function abnormalities in low birth weight neonates | FlammableCare must be taken to remove excess and allow to dry before using the electric scalpel | See comments on CHG y alcohol | See comments on PVP-I and alcohol | May be used for the treatment of chronic wounds. Not harmful for eyes or ears |

Source: Adapted from Card et al.7

The prepared area must be sufficiently large in order to allow for the extension of the incision or the placement of drains. The staff must have knowledge of the different techniques for skin preparation, including the preservation of skin integrity and the prevention of injuries to the skin.52 The preparation process must follow certain special considerations:

- •

Areas with large microbial counts must be the last to be prepared

- •

Colostomies must be isolated with antiseptic-impregnated gauze and left for the end of the preparation process

- •

The use of normal saline solution is recommended for preparing burnt or traumatized skin areas

- •

The use of chlorhexidine and alcohol-based products must be avoided in mucosal tissue

- •

Allow enough contact time for the antiseptic agents before draping

- •

Allow enough time for complete evaporation of flammable agents

- •

Prevent antiseptics to pool under the patient or the equipment

Skin preparation must be documented in the patient's chart. Skin preparation policies and procedures must be reviewed periodically in order to evaluate new evidence.

- •

Areas of the skin that will undergo therapeutic (surgery), anaesthetic (regional anaesthesia) and diagnostic (catheter insertion) procedures must be prepared with antiseptic solution in order to reduce the risk of infection [GRADE A1].

The use of shavers may result in cuts and skin abrasions and should not be allowed. The use of clipping devices is recommended for removing hair close to the skin, leaving behind hair that is 1mm long. Clippers usually have disposable heads, or reusable heads that may be disinfected between patients. They do not touch the skin, thus reducing cuts and abrasions. Hair removal creams dissolve hair through the chemical action of the product. However, the process is lengthier, lasting between 5 and 20min. Chemical hair removal may irritate the skin or give rise to allergic reactions. There are some special considerations for hair removal:

- •

Hair removal must be avoided, unless hair may interfere with the procedure55

- •

Hair removal must be the exception, not the rule

- •

When required, hair removal must be done as close to the time of the surgical procedure as possible. There is no evidence of a specific time period for avoiding hair removal on or close to the surgical site. Shaving more than 24h before the procedure increases the risk of infection56

- •

Hair removal in the sterile field may contaminate the surgical site and the drapes because of loose hair

- •

For some surgical procedures, hair removal may not be necessary. Patients requiring immediate surgical intervention may not have time for hair removal

- •

The staff in charge of removing hair must have the training in the use of the appropriate technique

- •

Policies and procedures must state when and how to remove hair at the incision site. Hair removal must be performed under the doctor's orders or in accordance with the protocol for certain surgical procedures

- •

If hair is removed, it must be documented in the clinical record. The documentation must include skin condition at the surgical site, the name of the person who did the hair removal, the method used, the area of the body and the time when it was done.

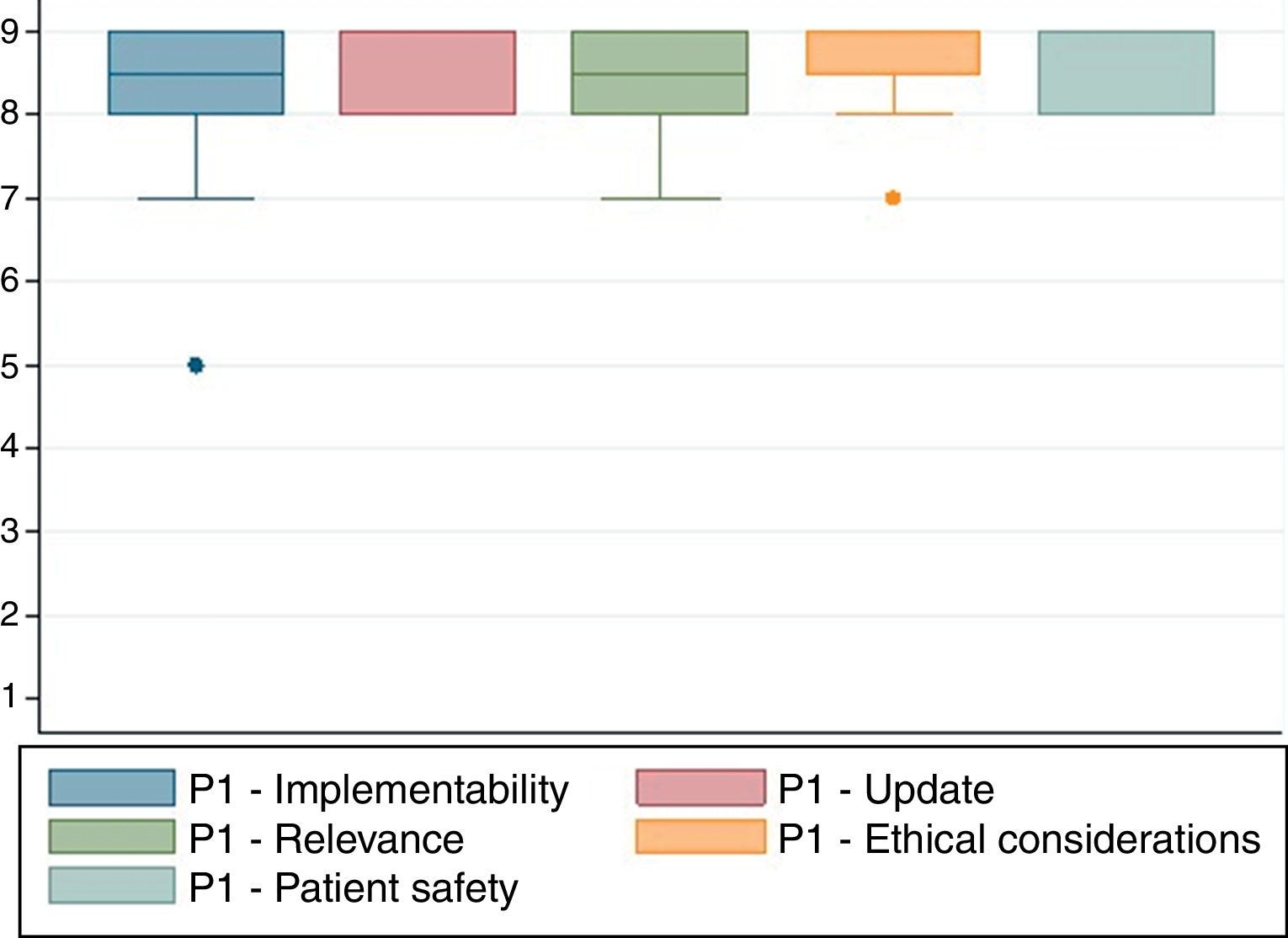

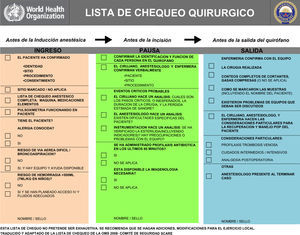

Checklists have become commonplace in healthcare practice as a strategy to improve patient safety. The World Health Organization (WHO) has implemented a proposed checklist in more than 120 countries (Fig. 3). Emphasis is made on the use of these lists for the most critical processes impacting patient safety:

- •

Safe anaesthesia and risk of a difficult airway

- •

Right surgical site

- •

Infection prevention

- •

Teamwork

Adapted by the Colombian Society of Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation.

The intent of the checklist as a safety tool is to standardize and increase performance predictability of the surgical team in a whole range of situations and clinical settings, and with different people.57 Hence, checklists have been equated with best practices in high-risk areas such as anaesthesia, and have been adopted in Colombia as a minimum safety standard in anaesthesiology.32,58

- •

In all patients undergoing surgical procedures, compliance with the pre-operative procedures, staff and equipment availability must be ascertained using the WHO checklist [GRADE A1].

The flow diagram of patient preparation for surgery shows several sequential sub-processes, each being a prerequisite for the next (Fig. 4).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rincón-Valenzuela DA, Escobar B. Manual de práctica clínica basado en la evidencia: preparación del paciente para el acto quirúrgico y traslado al quirófano. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2015;43:32–50.