We have carefully read the Manual of evidence-based clinical practice: patient preparation for surgery and transfer to the operating theater1 presented as a tool for rating healthcare institutions in Colombia, in addition to making it mandatory under the following statement: “… This protocol establishes the obligatory steps for a constant and systematic implementation on behalf of an informed and committed interdisciplinary team with the care and welfare of the surgical patient…”. Likewise, Colombian Society of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation (S.C.A.R.E.) webpage (http://www.scare.org.co/Scare-Gremial/Noticias/Un-aporte-para-la-habilitacion-de-servicios-de-sal.aspx) is published with the endorsement of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Cochrane Collaboration, and 28 Colombian anesthesiologists that participated in the deliberations.

This S.C.A.R.E. initiative is commendable, however we believe that the development process shall be improved since the Health Statutory Law (1571 of February 16, 2015), transfers to physicians and professional associations the responsibility for professional autonomy and self-regulation via guidelines, protocols, or any other tools for improving the quality of care for our patients. This entails serious legal implications and requires adapting to the reality of our practice and our healthcare system, making sure that there are no gaps, doubts, or free interpretations since these may become regulatory instruments at different levels in the system. The high level of the sponsors will turn this Manual into “lex artis” (Law of the Skill) making all protocols or institutional guidelines irrelevant in a medical-legal process.

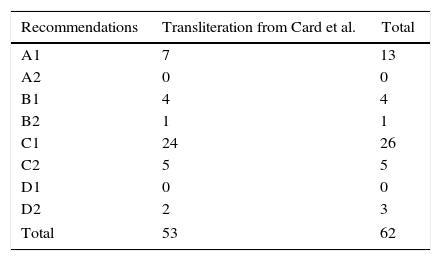

The document lists 62 recommendations with varying levels of evidence but quite a few are contradictory to the practice as shown by the current evidence; this is counterproductive because the endorsement should require the implementation of such recommendations, even at the expense of providing lower quality medical care.

When reviewing the endorsement 53 (85%) (Table 1) of the recommendations and several tables, although authorized by the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), are translated literally and not adapted from a perioperative protocol (https://www.icsi.org/_asset/0c2xkr/Periop.pdf) of an institute with little international recognition and written by a family doctor and other healthcare colleagues with no academic publications. It is then surprising that the literal translation of a document not endorsed by the US anesthesia society becomes mandatory in Colombia.

Two examples of the document's weakness:

“Obtaining [electrolytes] from patients chronically using digoxin, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor antagonists (ARAs) in recommended [GRADE D2].”

“Patients aged 65 or over may be considered for a preoperative electrocardiogram [GRADE C2].”

The original Card et al. document gives no references to support these recommendations. In the first case the AHA/ACC 2014 guidelines on cardiac patient evaluation for non-cardiac surgery, that have the strongest academic weight in the literature, fail to mention this aspect and clearly there are no literature references in PubMed either.

In the second case, the age-based recommendation to do an ECG was indicated in 2002, but since 2007 such indication was removed.2 In fact, there is ample literature showing that the ECG fails to predict perioperative cardiac events beyond the medical record, and hence its routine use is no longer practiced and some editorial articles are even reassessing its perioperative value.3,4

Base on this argument we respectfully suggest that S.C.A.R.E. considers the possibility to do a comprehensive review of this Manual since it may give rise to considerable medical-legal difficulties in the practice of anesthesiology in the country.

Likewise, we suggest that the Journal specifies the regulations for publishing piecemeal translations of documents that may be misleading with regards to the original authorship, as in this particular case. When 85% of the essence of a document (the recommendations) is translated literally, the authorship belongs to the original writers and not to the translators or those that compiled the material.

If assuming that the rest of the text (introduction and methods) was written mostly by the authors rather than the translation, the Instituto Colombiano de Normas Técnicas y Certificación (ICONTEC) standards for quotes shall be applicable, requiring the identification of direct quotes with quotation marks (less than six lines) with a footnote. If the quote is longer than six lines, it must be identified with the text source and each quote shall be marked with a reference number.5 If the Vancouver method for quotes is used, direct quotes shall be presented with quotation marks, with the exact page number of each quote.6

None of these guidelines are evidenced in the article published and this causes some confusion, since the clarification of having a translation license from Lippincott Williams and Wilkins/Wolters Kluwer Health, Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain & Ireland & the AAGBI Foundation, Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement is not an excuse for not explicitly defining the sources of each translated section, as required by the universally accepted quotation rules.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have nothing to disclose.

FundingThis article was written without any sponsorship.

Please cite this article as: Ibarra P, Zárate E, Robledo B, Arango E, Falls EB, Sarmiento Á, et al. Carta al editor: Manual de práctica clínica basado en la evidencia: preparación del paciente para el acto quirúrgico y traslado al quirófano. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2016;44:69–70.