The key role of the field of infectious diseases in other medical specialties, including anesthesiology, is currently well known. The anesthesiologist faces a potential risk of contributing to the development of healthcare associated infections in the operating rooms; however, the infectious complications derived from anesthesia have been underestimated. It is important to acknowledge that there are some deficiencies in research, notification, and publication of reports on anesthesia-associated infectious events in developing countries, particularly in Colombia, which is the focus of our attention in this article. As far as we know, only five countries – most of them developed – have carried out studies on the practices and knowledge of the anesthesiology personnel with regards to universal recommendations for the prevention and control of anesthesia-associated infections. This document discusses the importance of infections in the area of anesthesiology and at present in Colombia. Furthermore, the need to comply with basic infection prevention and control precautions and of creating awareness of safe injection practices is recognized.

Actualmente es bien conocido el protagonismo que el campo de las enfermedades infecciosas desempeña en otras especialidades médicas, incluyendo la anestesiología. El anestesiólogo tiene un riesgo potencial de contribuir al desarrollo de infecciones asociadas a la atención en salud en los quirófanos; sin embargo, las complicaciones infecciosas derivadas de la anestesia han sido subestimadas. Es importante reconocer que probablemente existen deficiencias en la investigación, notificación y publicación de reportes de eventos infecciosos asociados a la anestesia en países en vías de desarrollo, particularmente en Colombia en el cual nos hemos enfocado en el presente artículo. Hasta donde se sabe, únicamente cinco países, la mayoría de ellos desarrollados, han realizado estudios sobre prácticas y conocimientos del personal de anestesiología respecto a las recomendaciones universales para la prevención y el control de infecciones asociadas a la anestesia. En el presente documento se discute la importancia de las infecciones en el campo de la anestesiología y el panorama actual de su situación en Colombia. Además, se resalta la necesidad de adherencia a precauciones básicas de prevención y control de infecciones y de concientización sobre las prácticas seguras de inyección.

The leading role of the field of infectious disease in other medical specialties is currently widely known. There is a growing need each year to do research on infectious diseases, in view of the increasing implications of infectious diseases for the world population, making it an exciting public health area. Infectious complications are relevant, both in developed as in developing countries, with impact at the community and hospital level.

In particular, healthcare-associated infections (HCAI) are relevant because they present in multiple healthcare environments and cause considerable morbidity, mortality, hospitalization, and costs.1,2 In developed countries, 3.5–12% of hospitalized patients develop at least one HCAI, while in the developing countries this percentage varies from 5.7% to 19.1%.2

Today, the prevention and control of HCAIs in the surgical environment, including the anesthesiology staff, are mostly based on the understanding and practice of hand hygiene, hospital cleaning and disinfection (Ex., asepsis of the surgical site, sterilization of medical equipment), adequate implementation of invasive procedures, safe practices in the parenteral administration of medications, and use of sterile or new supplies3–5; however, these recommendations and standards are frequently forgotten, ignored or infringed by the healthcare staff. Preventing nosocomial infections is essential nowadays, considering the increase in the number of multiple drug resistant organisms.2,5,6

For a long time the HCAIs in the operating room were associated to a large extent with general asepsis failures in the surgical environment, the type of surgical procedure, and surgeon practices, forgetting the potential risk for the anesthesiology staff during surgery.3,6 The relevance of HCAIs in the area of anesthesiology has been evidenced for decades.7–9 This document discusses the importance of infections in anesthesiology and the outlook of this situation in Colombia, based on the available scientific evidence. Furthermore, emphasis shall be placed on the need to adhere to the basic recommendations regarding infection prevention and control, and to raise awareness about safe injection practices.

Risk factors associated with pre-surgical preparationJust as other branches in medicine, Anesthesiology is considered a dynamic medical specialty in terms of research and its professional practice focuses on the comprehensive care and safety of the patient. The prevention and control of HCAIs is one of the key pillars of an ideal anesthetic practice.

Anesthesiologists often invade the body's physiological and mechanical barriers when doing respiratory tract invasive procedures (tracheal intubation) and the cardiovascular system (venous or arterial accesses), or when performing local or neuraxial blocks. These procedures are potential sources for the transmission of microorganisms to patients and may lead to infection in the presence of gaps in the universal precautions of infection control or non-compliance with the recommended healthcare practices by the staff.3,10–13

Historically, a large number of common medical practices have been reported as risky, though they were originally intended to do good. These previously established practices have been reassessed in the light of new knowledge and so they have been banned or advised against because the current evidence suggests considerable risk for patients. In the area of anesthesiology it was for instance acceptable to reuse syringes for administering drugs to multiple patients, as long as the needle was changed, or to prepare intravenous injections using the same bag and administration channels for patients receiving the same therapy in one day.14–18 The risk of pathogen transmission among patients due to these practices is high, but we know it is totally preventable when these practices are abandoned.19 Unfortunately, it has been shown that anesthesiologists often are unaware of the importance of being compliant with all hygiene precautions and of the fact that they are actually mechanical vectors of pathogens everyday, since they are frequently in contact with infected patients.8,20

Although the cause–effect relationships in the practice of anesthesia and post-surgical infections are difficult to establish,11 multiple publications since 1972 have associated anesthetic practices and equipment or contaminated anesthetic products with bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.10,21–33 Unfortunately, in some of these cases there have been hospital outbreaks, resulting in considerable morbidity or mortality.10,22,23,26–28,30,32,33 However, it is thought that outbreaks are just a proportion of the true burden of disease derived from unsafe drug injection practices and hospital gaps in infection control.34 Specifically, infections from Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) may go undetected since these are initially asymptomatic, mildly symptomatic or unspecific.4

Risky behaviors in the operating roomSome of the mechanisms of transmission of frequently indiscriminate microorganisms in cases of anesthesia-associated infection include: reuse of single-use vials,23,26 reuse of vials or multidose vials in multiple patients,24,25,27,30,32,33 reuse of syringes or needles in multiple patients.22,23

Propofol in particular is the anesthetic drug more often involved in infectious events due to its lipid emulsion that promotes bacterial growth and due to its frequent wrongful manipulation (for example, reusing syringes or vials in multiple patients, poor external disinfection of the vial,35 and continuous propofol infusion) that facilitates its contamination.36 As we documented in a recent systematic review of the risk of infections with the use of propofol,36 all propofol-associated HCAIs have been reported in developed countries. This difference in scientific evidence does not seem to be different with other anesthetic products and practices studied with regards to microbial contamination or infection. Moreover, a recent systematic review on septic meningitis associated with regional anesthesia, showed the absence of clinical evidence in developing countries (Zorrilla-Vaca A., et al. Clinical occurrence of septic meningitis after spinal and epidural anesthesia, 1900–2015: a systematic review and peer reviewed). Although both anesthetic techniques show risks of infectious complications, according to a recent meta-analysis general anesthesia seems to be more closely associated.37 In general, our literature search suggests that developing countries lack scientific evidence of anesthesia-associated complications or specific anesthetic practices.

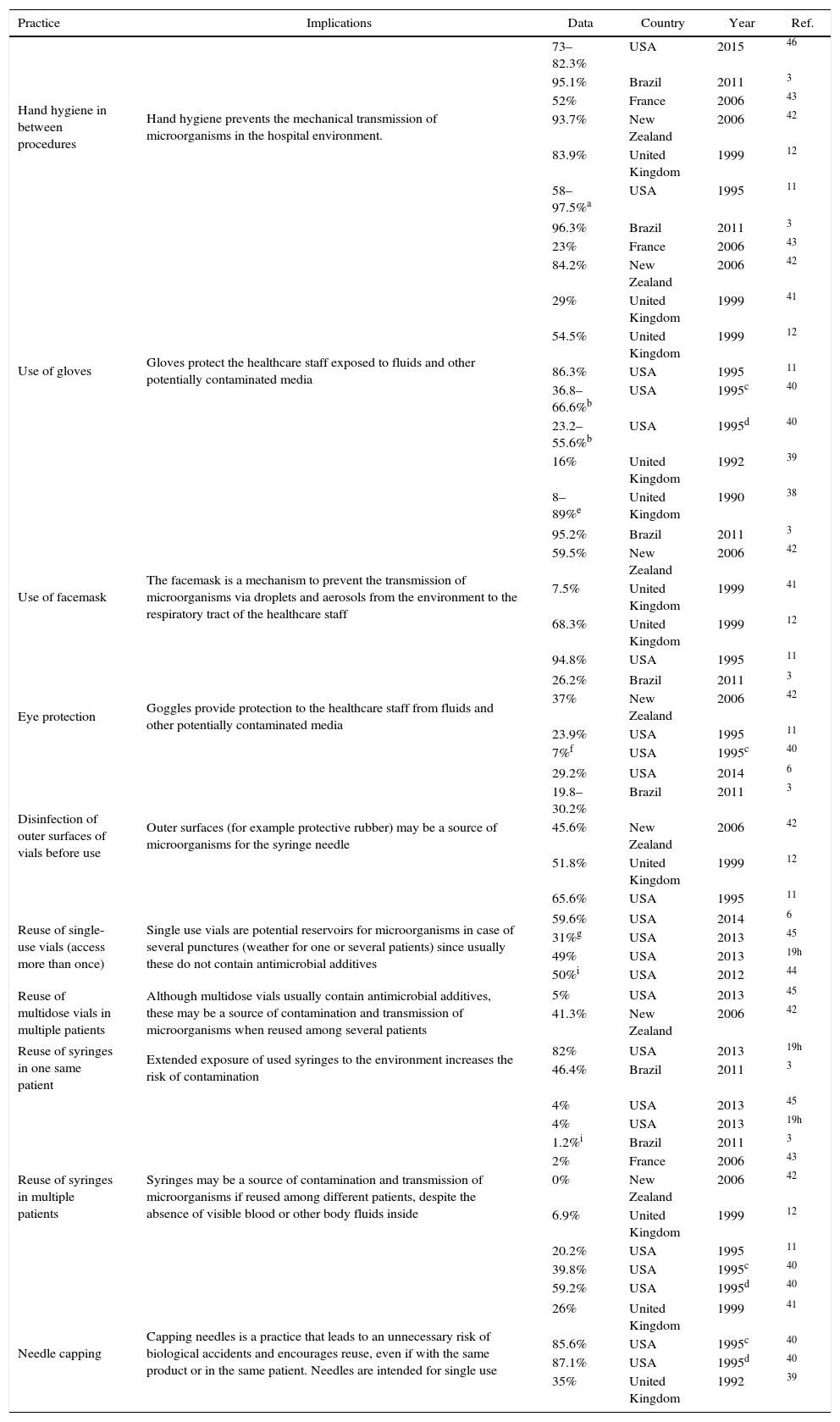

One of the most researched topics is the compliance of the anesthesiologist with the recommended hygiene, prevention, and control measures, including safe injection practices involving the set of measures implemented in order to administer injections in a safe manner for the patient, the healthcare staff and third parties. Table 1 illustrates the main findings of world cross-sectional trials aimed at identifying the level of compliance with the practice and the knowledge of hygiene and biosafety of the anesthesiology staff.3,6,11,12,19,38–46 Several of these practices have been involved in the perioperative transmission of microorganisms and anesthesia-associated risk of post-surgical infection. It is concerning to find high percentage of reuse of single-use vials (50%–59.6%), reuse of multidose in multiple patients (41.3%), reuse of syringes in the same patient (46.4–82%) and reuse of syringes in multiple patients (39.8–59.2%). While there is evidence that the reuse of syringes in different patients has decreased in the most recent studies, other unsafe injection practices have remained constant or increased. Hand hygiene and the use of gloves and facemask, show a higher percentage of compliance in the most recent trials.

Findings of studies done in anesthesiology staff on hygiene practices and biosafety knowledge for the prevention of transmission of microorganisms.

| Practice | Implications | Data | Country | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand hygiene in between procedures | Hand hygiene prevents the mechanical transmission of microorganisms in the hospital environment. | 73–82.3% | USA | 2015 | 46 |

| 95.1% | Brazil | 2011 | 3 | ||

| 52% | France | 2006 | 43 | ||

| 93.7% | New Zealand | 2006 | 42 | ||

| 83.9% | United Kingdom | 1999 | 12 | ||

| 58–97.5%a | USA | 1995 | 11 | ||

| Use of gloves | Gloves protect the healthcare staff exposed to fluids and other potentially contaminated media | 96.3% | Brazil | 2011 | 3 |

| 23% | France | 2006 | 43 | ||

| 84.2% | New Zealand | 2006 | 42 | ||

| 29% | United Kingdom | 1999 | 41 | ||

| 54.5% | United Kingdom | 1999 | 12 | ||

| 86.3% | USA | 1995 | 11 | ||

| 36.8–66.6%b | USA | 1995c | 40 | ||

| 23.2–55.6%b | USA | 1995d | 40 | ||

| 16% | United Kingdom | 1992 | 39 | ||

| 8–89%e | United Kingdom | 1990 | 38 | ||

| Use of facemask | The facemask is a mechanism to prevent the transmission of microorganisms via droplets and aerosols from the environment to the respiratory tract of the healthcare staff | 95.2% | Brazil | 2011 | 3 |

| 59.5% | New Zealand | 2006 | 42 | ||

| 7.5% | United Kingdom | 1999 | 41 | ||

| 68.3% | United Kingdom | 1999 | 12 | ||

| 94.8% | USA | 1995 | 11 | ||

| Eye protection | Goggles provide protection to the healthcare staff from fluids and other potentially contaminated media | 26.2% | Brazil | 2011 | 3 |

| 37% | New Zealand | 2006 | 42 | ||

| 23.9% | USA | 1995 | 11 | ||

| 7%f | USA | 1995c | 40 | ||

| Disinfection of outer surfaces of vials before use | Outer surfaces (for example protective rubber) may be a source of microorganisms for the syringe needle | 29.2% | USA | 2014 | 6 |

| 19.8–30.2% | Brazil | 2011 | 3 | ||

| 45.6% | New Zealand | 2006 | 42 | ||

| 51.8% | United Kingdom | 1999 | 12 | ||

| 65.6% | USA | 1995 | 11 | ||

| Reuse of single-use vials (access more than once) | Single use vials are potential reservoirs for microorganisms in case of several punctures (weather for one or several patients) since usually these do not contain antimicrobial additives | 59.6% | USA | 2014 | 6 |

| 31%g | USA | 2013 | 45 | ||

| 49% | USA | 2013 | 19h | ||

| 50%i | USA | 2012 | 44 | ||

| Reuse of multidose vials in multiple patients | Although multidose vials usually contain antimicrobial additives, these may be a source of contamination and transmission of microorganisms when reused among several patients | 5% | USA | 2013 | 45 |

| 41.3% | New Zealand | 2006 | 42 | ||

| Reuse of syringes in one same patient | Extended exposure of used syringes to the environment increases the risk of contamination | 82% | USA | 2013 | 19h |

| 46.4% | Brazil | 2011 | 3 | ||

| Reuse of syringes in multiple patients | Syringes may be a source of contamination and transmission of microorganisms if reused among different patients, despite the absence of visible blood or other body fluids inside | 4% | USA | 2013 | 45 |

| 4% | USA | 2013 | 19h | ||

| 1.2%i | Brazil | 2011 | 3 | ||

| 2% | France | 2006 | 43 | ||

| 0% | New Zealand | 2006 | 42 | ||

| 6.9% | United Kingdom | 1999 | 12 | ||

| 20.2% | USA | 1995 | 11 | ||

| 39.8% | USA | 1995c | 40 | ||

| 59.2% | USA | 1995d | 40 | ||

| Needle capping | Capping needles is a practice that leads to an unnecessary risk of biological accidents and encourages reuse, even if with the same product or in the same patient. Needles are intended for single use | 26% | United Kingdom | 1999 | 41 |

| 85.6% | USA | 1995c | 40 | ||

| 87.1% | USA | 1995d | 40 | ||

| 35% | United Kingdom | 1992 | 39 | ||

Percentage use of gloves depending on type of practice (venous catheterization, arterial catheterization).

Percentage use of gloves depending on the type of practice (tracheal intubation, peripheral cannulation, central cannulation).

Percentage use of eye protection among the group of anesthesiologists that do not use prescription glasses.

Woodbury et al. determined that among the 89 professionals involved in anesthesia, the primary factors preventing them from using brand new materials under certain circumstances in their clinical practice was costs (71%), convenience/efficiency (36%), environmental impact (16%), time (12%) or negligence (4%).6 Gounder et al. also determined among 522 anesthesiologists that the major barriers to use vials of new medicines for multiple patients were the shortage of drugs (44%), the intention to reduce wastage (44%), in addition to high costs (27%).45 None of these factors, including cost savings, justifies reuse practices against the current recommendations; for instance, the cost of a iatrogenic infection case is certainly higher than the cost of using new materials, not to mention the ethical implications involving human distress and harmful consequences.6,42

Few studies have been completed on epidemiological surveillance of anesthesia-associated infections. A Japanese trial reported that 8.3% of 6,437 patients undergoing surgery in a two-year period were infected with a virus (HBV, HCV or HIV) prior to surgery.20 Another multicenter trial in France determined a 3.4 per every 1000 patients of anesthesia-associated hospital acquired infections.47

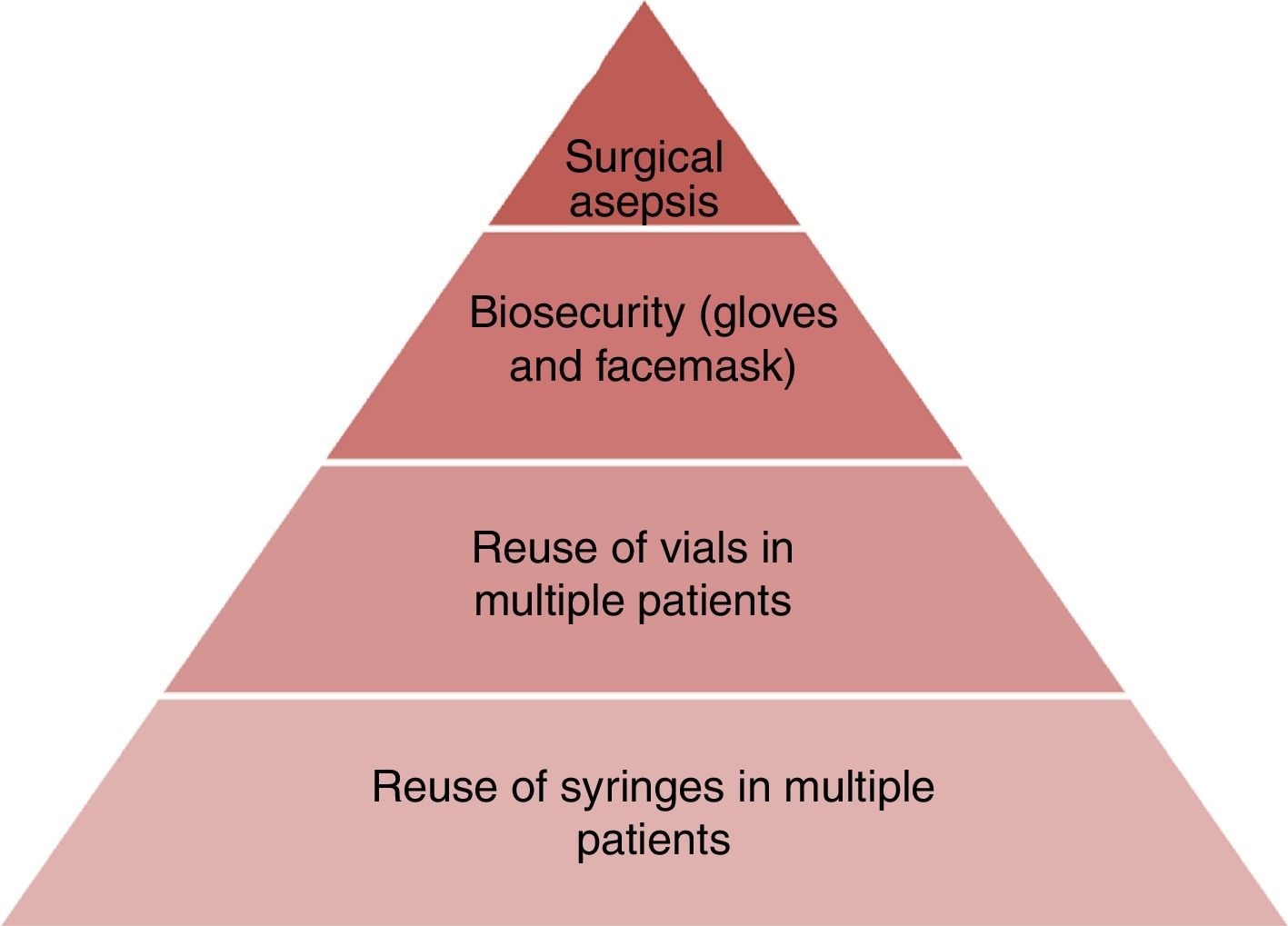

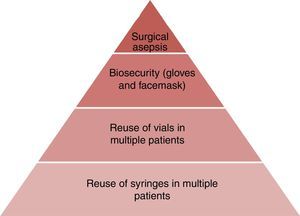

Overall, the findings herein presented emphasize the need for further education and the importance of adhering to the universal recommendations and basic infection control guidelines. However, some professionals, despite their knowledge of the information fail to change their practice habits if they are not fully convinced about the impact and the reasons behind the recommendations. Consequently, stressing the negative outcomes associated with unsafe injection practices may have a positive effect.6 A poor hygiene practice by one single anesthesiologist, may result in catastrophic infectious events for multiple patients in a healthcare institution, not only placing patients at risk, but also jeopardizing the professional's job performance.42 Anesthesia providers have the responsibility and the opportunity to give patients good healthcare, so they most ensure the safe administration of medications and suitable performance of anesthetic procedures.6 The difficulties in developing countries – still unknown – should be considerably more severe as compared to the developed countries. It is then absolutely necessary to undertake national trials to validate the injection and manipulation practices of anesthetic agents by the anesthesiology staff. Fig. 1 illustrates the hierarchy of risk factors for anesthesia-associated infectious complications.

Surveillance and control in ColombiaAt the end of our literature search, no studies were found on infections in anesthesia in Colombia, which suggests big gaps in the knowledge and awareness about the issue. In Colombia, probably the only paper on the topic was a study we recently published, showing that 6.1% of propofol vials used in the operating rooms in a third level hospital were contaminated after being used for anesthesia.48 Although the clinical impact of this finding was not measured, surprisingly enough we found that only 26.1% of the vials used were punctured just once. A recent cross-sectional research at the national level established that the level of reuse of vials and syringes was 37.9% and 6.2%, respectively.49

Apparently Colombia has no specific published recommendations on anesthetic handling or guidelines for the prevention and control of anesthesia-related infections. In contrast, countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Spain, Hong Kong, and South Africa do have protocols and hygiene guidelines for the prevention and control of anesthesia-associated infections.50–56

Despite the low research interest of anesthesiology in infectious disease at the national level, it is important to highlight some of the activities sponsored by the Colombian Society of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation (S.C.A.R.E.) such as the “Revised-Comprehensive Surgical Risk Measurement” program (MIRQ-R) implemented by the promotion and prevention area, the XXXI Colombian Congress of Anesthesiology that focused on “Patient Safety” and a recent publication in the Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology entitled “Evidence-based Clinical Practice Manual: patient preparation for surgery and transfer to the operating room”.57

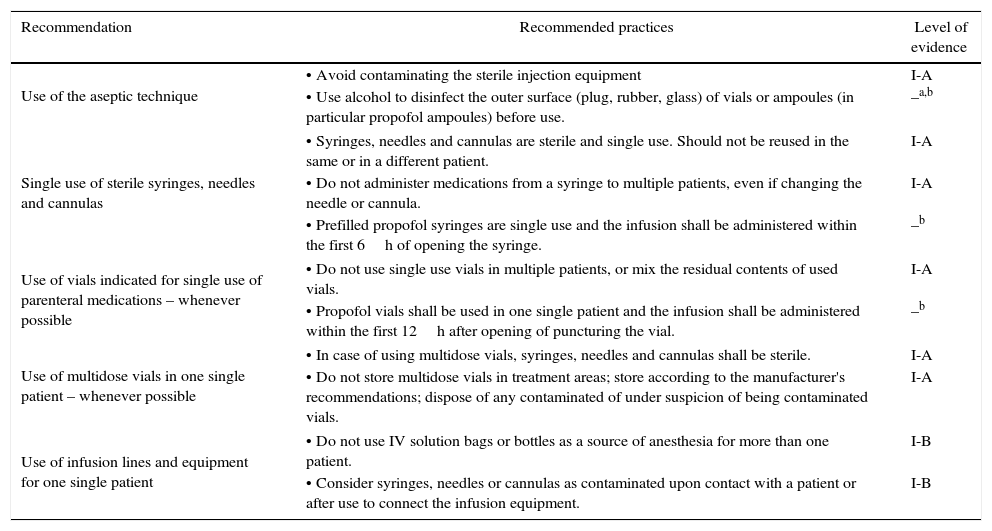

Various strategies and educational advances have been implemented in other countries. In June 2008, the Coalition of Safe Injection Practices was founded with the aim of stopping unsafe injection practices in the United States.58 This coalition, together with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), launched the “One and Only Campaign” with a view to raise awareness among the healthcare professionals and the general public about safe injection practices (Fig. 2). The name of the campaign addresses the use of a needle and a syringe for a single injection in one patient. Table 2 illustrates the key recommendations for safe injection practices.59

Key recommendations for safe injection practices.

| Recommendation | Recommended practices | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Use of the aseptic technique | • Avoid contaminating the sterile injection equipment | I-A |

| • Use alcohol to disinfect the outer surface (plug, rubber, glass) of vials or ampoules (in particular propofol ampoules) before use. | –a,b | |

| Single use of sterile syringes, needles and cannulas | • Syringes, needles and cannulas are sterile and single use. Should not be reused in the same or in a different patient. | I-A |

| • Do not administer medications from a syringe to multiple patients, even if changing the needle or cannula. | I-A | |

| • Prefilled propofol syringes are single use and the infusion shall be administered within the first 6h of opening the syringe. | –b | |

| Use of vials indicated for single use of parenteral medications – whenever possible | • Do not use single use vials in multiple patients, or mix the residual contents of used vials. | I-A |

| • Propofol vials shall be used in one single patient and the infusion shall be administered within the first 12h after opening of puncturing the vial. | –b | |

| Use of multidose vials in one single patient – whenever possible | • In case of using multidose vials, syringes, needles and cannulas shall be sterile. | I-A |

| • Do not store multidose vials in treatment areas; store according to the manufacturer's recommendations; dispose of any contaminated of under suspicion of being contaminated vials. | I-A | |

| Use of infusion lines and equipment for one single patient | • Do not use IV solution bags or bottles as a source of anesthesia for more than one patient. | I-B |

| • Consider syringes, needles or cannulas as contaminated upon contact with a patient or after use to connect the infusion equipment. | I-B | |

Level I-A: strongly recommended practice for implementation and with strong evidence based on well designed experimental, clinical or epidemiological studies.

Level I-B: strongly recommended practice for implementation and evidence-based on some experimental, clinical or epidemiological studies and a strong theoretical foundation.

There are several explanations for the lack of interest of anesthesiology in infectious diseases, particularly in developing countries such as Colombia: (1) limited knowledge about prevention and control guidelines in Health Care Associated Infections, (2) the lack of awareness regarding patient safety in surgical hospital environments, (3) minimal epidemiological follow-up and surveillance of HCAIs in the operating room, (4) little economic support for implementing research activities and doing a local analysis of healthcare centers relevant data, (5) research preferences favoring mechanical applications and physiological principles of anesthesia, instead of researching adverse events associated with anesthetics contamination and basic cleansing and disinfection procedures, and (6) the perception that infectious diseases are beyond the scope or unfamiliar to anesthesiology.

We believe that the following aspects may generate increased interest: (1) the severe clinical consequences of a practice of anesthesia that fails to comply with the universal recommendations on hygiene and infections prevention and control, (2) the growing generalized interest of epidemiological surveillance to learn about the outcomes associated with anesthetic procedures, (3) the actions of professional anesthesiologists avoiding legal issues due to malpractice or medical negligence, and (4) the need to fight and prevent antimicrobial resistance.

ConclusionsThe anesthesiologist faces the potential risk of contributing to the development of HCAIs in the OR; however, infectious complications from anesthesia have been underestimated. In our country, infectious diseases are not as significant in anesthesiology as in other medical specialties, but this is not due to lack of merits. Despite the strong bond between the anesthesiologist and patient safety, there are few studies that clearly depict the epidemiology of anesthesia-associated infections as one of the potential healthcare complications. It is important to acknowledge that there are some flaws in research, notification and reporting of anesthesia-associated infectious events in Colombia. The knowledge and practices of the anesthesiology staff in our country with regards to the universal recommendations for the prevention and control of anesthesia-associated infections are also unknown. Research in the area of anesthesia-associated infectious diseases would be a novelty for the healthcare staff.

FundingAndres Zorrilla-Vaca received a research grant from S.C.A.R.E.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.