Goal oriented sedation is standard in the management of critically ill patients, but its systematic evaluation is not frequent. The Richmond agitation sedation scale's efficient operative features make it a validated instrument for sedation assessment.

ObjectivesTo translate and validate the Richmond agitation sedation scale into Spanish.

MethodA cultural and linguistic adaptation study was designed. Translation into Spanish included back-translation and pilot testing. The inter-rater reliability testing was conducted in Clínica Colombia's cardiovascular and general intensive care unit, including 100 patients mechanically ventilated and sedated. Inter-rater reliability was tested using Kappa statistics and Intra-class correlation coefficient. This study was approved by Fundación Universitaria Sanitas Research and Ethics Institute and Clínica Sanitas Research Committee.

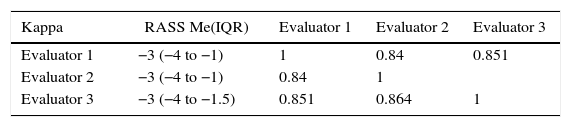

Results300 assessments using the Spanish version of the Richmond agitation sedation scale were performed by three independent evaluators. The intra-class correlation coefficient was 0.977 (CI 95% 0.968–0.984). The kappa was 0.84 between the first and second evaluators 0.85 between the first and third evaluators and 0.86 between the second and third evaluators.

ConclusionThe product of this study, the Spanish version of the Richmond agitation sedation scale, is conceptually equivalent to the original scale, being reproducible and understandable to physicians whose native language is Spanish.

La sedación por metas es un estándar en el manejo del paciente crítico pero su evaluación sistemática no es frecuente, la escala de sedación y agitación Richmond es un instrumento con características operativas eficientes para evaluar sedación.

ObjetivoTraducir y validar la escala de sedación y agitación Richmond al idioma español.

MétodoSe diseñó un estudio de adaptación transcultural y lingüística y validación de instrumento. La traducción al idioma español incluyó una traducción reversa y una prueba piloto. Las evaluaciones para la validación se realizaron con 100 pacientes bajo sedación, ventilados mecánicamente en dos unidades de cuidados intensivos, una polivalente y otra cardiovascular de la Clínica Universitaria Colombia. La fiabilidad entre los observadores fue probada utilizando el estadístico kappa y el coeficiente de correlación intraclase. El estudio contó con la aprobación del instituto de investigaciones y comité de ética de la Fundación Universitaria Sanitas y comité de investigaciones de Clínica Sanitas.

ResultadosSe realizaron evaluaciones secuenciales e independientes por tres entrevistadores, completando 300 valoraciones con la traducción de la escala en español. El coeficiente de correlación intraclase fue de 0,977 (IC 95% 0,968 - 0,984). La concordancia cualitativa entre los evaluadores también fue alta con un kappa de 0,84 entre el primer y segundo evaluador, 0,85 entre el primer y tercer evaluador y 0,86 entre el segundo y tercero.

ConclusiónLa versión en español de la escala de sedación y agitación Richmond producto de este estudio, resulta conceptualmente equivalente a la original, es reproducible y comprensible para médicos de habla hispana.

Goal oriented sedation has become standard in the management of critical patients, with notable benefits in clinical outcomes.1 It allows for an adequate level of patient–ventilator interaction, alleviates patient anxiety about medical care, favors sleep architecture by conserving the sleep–wake cycle, increases tolerance to procedures like tracheal aspiration, and reduces the frequency of unexpected events like self-extubation and the removal of intravascular devices.2,3 Another benefit described and associated with an appropriate sedation plane in critical patients is the lower quantity of circulating systemic catecholamines with a decrease in oxygen consumption.4 It has also been credited with lower barotrauma in patients with reduced pulmonary compliance.5

Deep sedation, on the other hand, leads to a series of risks that are potentially avoidable for the patient: increase in the incidence of ventilation-associated pneumonia,6 more days on mechanical ventilation,7 prolonged hospital stay, difficulty in neurological evaluations, and neuromuscular weakness in the critical patient.8

Although sedation is universally used in intensive care services, its systematic evaluation is infrequent.9 Objective and subjective methods exist for evaluating sedation.10 Overall, the subjective evaluation of the level of sedation through scales is preferred to more elaborate techniques.11 Any evaluation instrument in medicine must be validated and submitted to processes of cultural and linguistic adaptation in order to avoid barriers in the application and the variability in the results.12

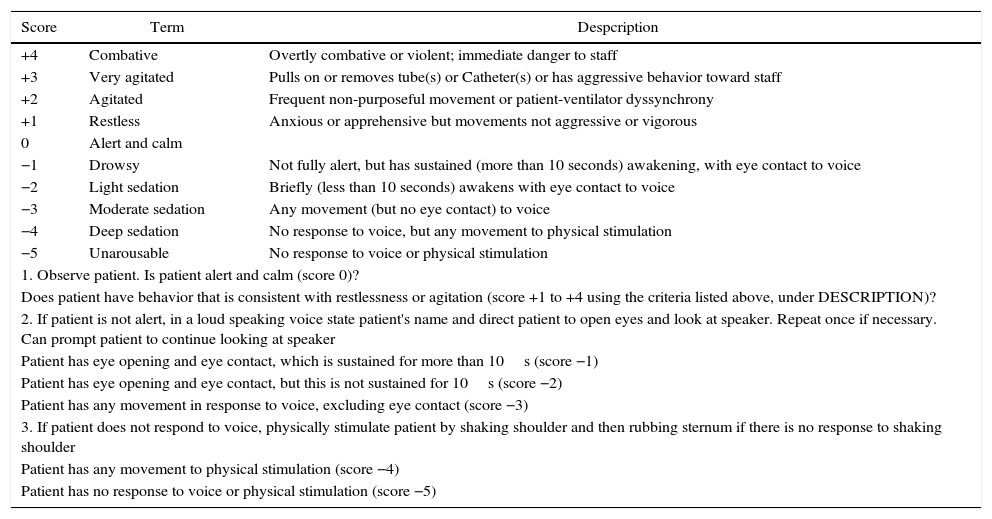

One of the scales with efficient operative characteristics and reproducibility in the systematic evaluation of sedation is the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS).13 The RASS was developed in 2012 by a multidisciplinary group in the University of Richmond, USA. It consists of a 10-point scale that can quickly evaluate a patient and place them in a level of sedation or agitation through three clearly defined steps14 (Table 1). The RASS is widely used, even in countries like Colombia. It has been validated in other languages such as French,15 Swedish16 and Portuguese,17 but no reports exist of official translations or validations into Spanish.

Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS).

| Score | Term | Despcription |

|---|---|---|

| +4 | Combative | Overtly combative or violent; immediate danger to staff |

| +3 | Very agitated | Pulls on or removes tube(s) or Catheter(s) or has aggressive behavior toward staff |

| +2 | Agitated | Frequent non-purposeful movement or patient-ventilator dyssynchrony |

| +1 | Restless | Anxious or apprehensive but movements not aggressive or vigorous |

| 0 | Alert and calm | |

| −1 | Drowsy | Not fully alert, but has sustained (more than 10 seconds) awakening, with eye contact to voice |

| −2 | Light sedation | Briefly (less than 10 seconds) awakens with eye contact to voice |

| −3 | Moderate sedation | Any movement (but no eye contact) to voice |

| −4 | Deep sedation | No response to voice, but any movement to physical stimulation |

| −5 | Unarousable | No response to voice or physical stimulation |

| 1. Observe patient. Is patient alert and calm (score 0)? | ||

| Does patient have behavior that is consistent with restlessness or agitation (score +1 to +4 using the criteria listed above, under DESCRIPTION)? | ||

| 2. If patient is not alert, in a loud speaking voice state patient's name and direct patient to open eyes and look at speaker. Repeat once if necessary. Can prompt patient to continue looking at speaker | ||

| Patient has eye opening and eye contact, which is sustained for more than 10s (score −1) | ||

| Patient has eye opening and eye contact, but this is not sustained for 10s (score −2) | ||

| Patient has any movement in response to voice, excluding eye contact (score −3) | ||

| 3. If patient does not respond to voice, physically stimulate patient by shaking shoulder and then rubbing sternum if there is no response to shaking shoulder | ||

| Patient has any movement to physical stimulation (score −4) | ||

| Patient has no response to voice or physical stimulation (score −5) | ||

The creation of a scale is a complex process. The process of adaptation and validation is more quickly achieved since it originates from a tested instrument. The difference in languages or cultures may affect the way in which it is applied or in which one responds to an instrument of measurement. As such, linguistic equivalence is an obligatory step in the validation of an instrument to another language.

The objective of this endeavor was to create a linguistic equivalent of the RASS and validate the version translated into Spanish in order to have a tool for Spanish-speaking physicians that would allow them to monitor the level of sedation in adult critical patients.

MethodologyThe protocol was approved by the Research Committee of the Sanitas University Foundation of Colombia. According to Resolution No. 008430 of 1993 of the Colombian Ministry of Health, which regulates research on human beings in Colombia, this study is classified in the “no risk” category. There was no requirement of informed consent. The study was carried out in two phases: first, the translation of the RASS from English to Spanish, followed by the measurement of the reliability of the translated scale. This later phase was performed in both intensive care units of the Colombia University Clinic, a university health center with fourth level complexity and 28 intensive care beds: 13 for polyvalent care and 15 for cardiovascular care.

Phase 1: translation and linguistic equivalency of the scaleA translation and cultural adaptation of the RASS from its original language to Spanish was performed based on ISPOR norms.18 The linguistic equivalency was achieved through a series of stages, with recorded proceedings of each result and individual conclusion:

Preparation: Permission was requested from the original author of the RASS, Dr. Curtis Sessler. He conceded this permission.

Initial Translation: Two native authors with fluency in both languages translated the scale from English to Spanish and compared their results.

Reconciliation: Resolution of discrepancies between the original and the translations by third native translator.

Back-Translation: The RASS in Spanish was translated back into English by a bilingual physician without knowledge of the scale in the original language.

Review of the Quality of the Back Translation and Harmonization of conceptual discrepancies in the items of the scale. Carried out by the group of researchers.

Cognitive Review: Evaluation of understanding through a survey of 20 specialists in Critical Medicine. The goal was to determine comprehensibility, understanding, writing, spelling, and difficulties that arise when the translated scale is applied.

Final correction of grammatical and typographic errors.

Final Report: The final, translated and corrected version of the RASS in Spanish is presented. With this product, a pilot trial on 30 patients was performed to familiarize the evaluators with the translated instrument.

Phase 2: inter-evaluator reliability of the RASS in SpanishThe reliability tests between evaluators were performed on 100 sedated adult patients that received invasive mechanical ventilation in the Intensive Care Units of the Colombia University Clinic between February, 2013 and July, 2014.

Each patient was submitted to grading by a multidisciplinary group made up of three evaluators: two physicians with a first specialty either in Internal Medicine or Anesthesiology, but both with a second specialty in Critical Medicine, and a third specialist in Critical Medicine and Intensive Care.

The evaluations were performed consecutively and independently by the three evaluators at different times of the day or the night. The order of the graders was chosen randomly and they were blinded to the grades of the others. Pharmaceuticals administered for the sedation was part of the institutional protocol aimed at addressing the patient's clinical condition.

Statistical analysisThe numerical variables were submitted to normality testing with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Depending on their distribution, they are summarized with averages and standard deviation or median and interquartile range. The categorical variables are expressed in relative frequencies and percentages. The RASS is, by definition, an ordinal variable, but it has 10 defined levels in numerical values, which permits its quantitative analysis. To measure the inter-observer reliability, the coefficient of intra-class correlation (CIC) for quantitative data and Cohen's kappa statistic were used for the categorical variables. With a CIC greater than 0.8, the evaluators were considered to be in almost perfect agreement, and a kappa value of 1 means complete agreement. The information was analyzed with the statistical program IBM®SPSS® version 22.

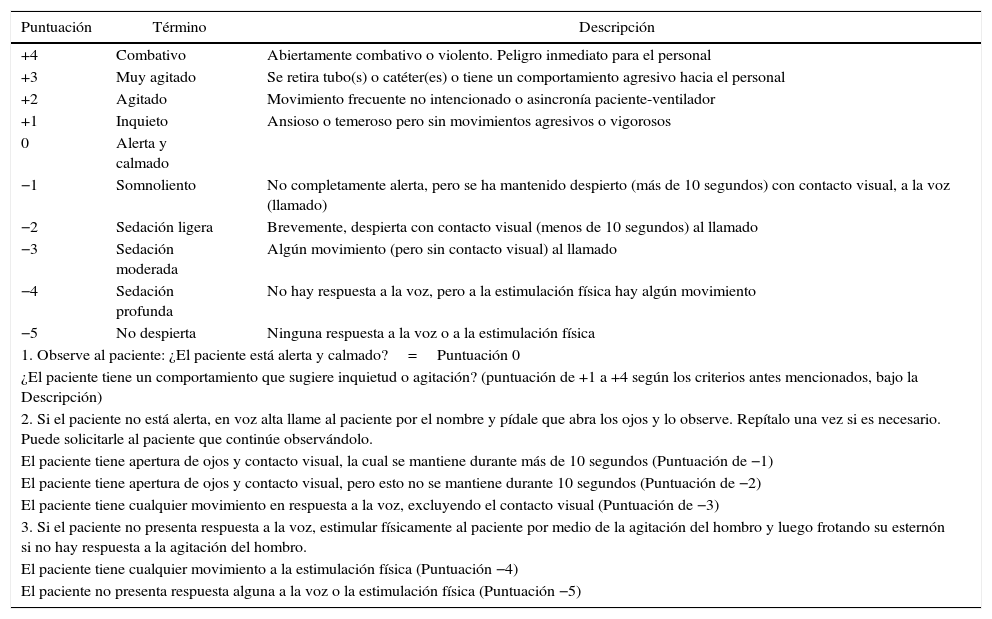

ResultsTranslation phaseThe product of this phase is the translated, corrected and unified version of the scale in Spanish. 30 patients were used in the pilot test. 90 measurements of the level of sedation were made, and the objective of familiarizing and accepting the new instrument was achieved (see Table 2).

Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) in Spanish.

| Puntuación | Término | Descripción |

|---|---|---|

| +4 | Combativo | Abiertamente combativo o violento. Peligro inmediato para el personal |

| +3 | Muy agitado | Se retira tubo(s) o catéter(es) o tiene un comportamiento agresivo hacia el personal |

| +2 | Agitado | Movimiento frecuente no intencionado o asincronía paciente-ventilador |

| +1 | Inquieto | Ansioso o temeroso pero sin movimientos agresivos o vigorosos |

| 0 | Alerta y calmado | |

| −1 | Somnoliento | No completamente alerta, pero se ha mantenido despierto (más de 10 segundos) con contacto visual, a la voz (llamado) |

| −2 | Sedación ligera | Brevemente, despierta con contacto visual (menos de 10 segundos) al llamado |

| −3 | Sedación moderada | Algún movimiento (pero sin contacto visual) al llamado |

| −4 | Sedación profunda | No hay respuesta a la voz, pero a la estimulación física hay algún movimiento |

| −5 | No despierta | Ninguna respuesta a la voz o a la estimulación física |

| 1. Observe al paciente: ¿El paciente está alerta y calmado?=Puntuación 0 | ||

| ¿El paciente tiene un comportamiento que sugiere inquietud o agitación? (puntuación de +1 a +4 según los criterios antes mencionados, bajo la Descripción) | ||

| 2. Si el paciente no está alerta, en voz alta llame al paciente por el nombre y pídale que abra los ojos y lo observe. Repítalo una vez si es necesario. Puede solicitarle al paciente que continúe observándolo. | ||

| El paciente tiene apertura de ojos y contacto visual, la cual se mantiene durante más de 10 segundos (Puntuación de −1) | ||

| El paciente tiene apertura de ojos y contacto visual, pero esto no se mantiene durante 10 segundos (Puntuación de −2) | ||

| El paciente tiene cualquier movimiento en respuesta a la voz, excluyendo el contacto visual (Puntuación de −3) | ||

| 3. Si el paciente no presenta respuesta a la voz, estimular físicamente al paciente por medio de la agitación del hombro y luego frotando su esternón si no hay respuesta a la agitación del hombro. | ||

| El paciente tiene cualquier movimiento a la estimulación física (Puntuación −4) | ||

| El paciente no presenta respuesta alguna a la voz o la estimulación física (Puntuación −5) | ||

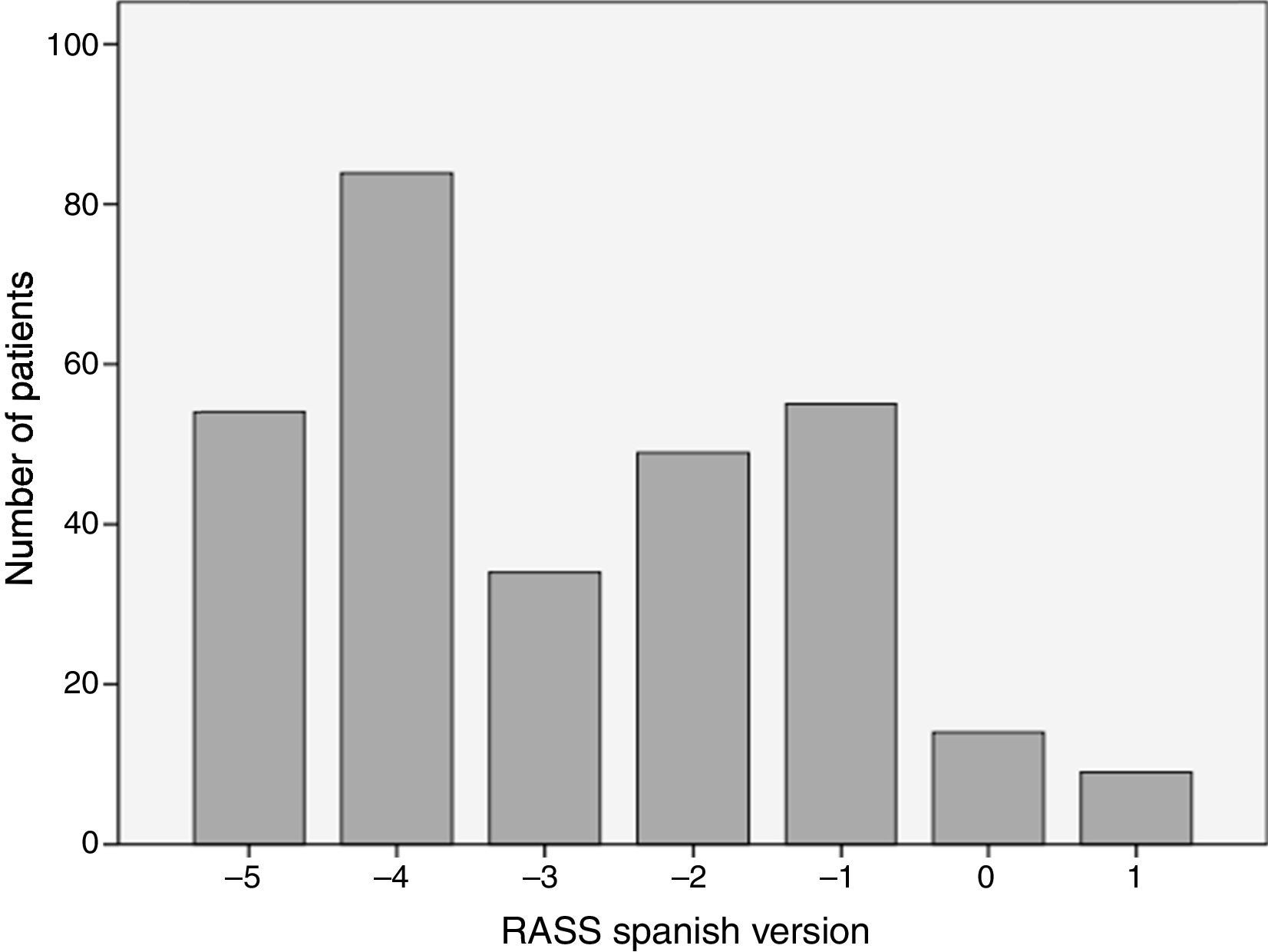

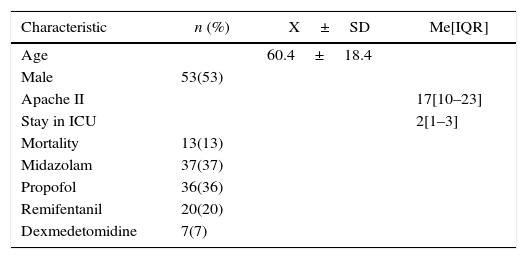

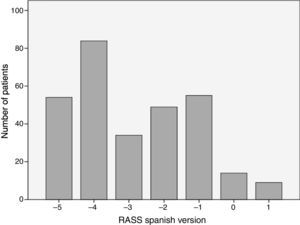

The analyzed series consisted of 100 adult patients with a median age of 63 years, 53% male; the median stay in the ICU was 2 days IQR [1–3], while that of the Apache II score was 17 IQR [10–23] (see Table 3). The patients came from two intensive care units with different medical care profiles, some polyvalent and others cardiovascular. This allowed for the application of the scale in varying clinical scenarios, including: neuro-intensivism, surgery due to major trauma, post-operative care for heart surgery and sepsis. Each patient included in the study was submitted to three consecutive evaluations. A distribution of grades between the categories −5 and 1 was found. The mode was category −4, and 37% of the patients were cataloged under superficial sedation — −2 to 0 — (see Fig. 1). The sedation of the patients was performed with midazolam in 37% of patients, propofol in 36%, remifentanil in 20%, and, in 7% of patients, conscious sedation with dexmedetomidine. All options were combined with opioid analgesics in accordance with the patients’ needs (see Table 3).

Characteristics of patients included in the study.

| Characteristic | n (%) | X±SD | Me[IQR] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.4±18.4 | ||

| Male | 53(53) | ||

| Apache II | 17[10–23] | ||

| Stay in ICU | 2[1–3] | ||

| Mortality | 13(13) | ||

| Midazolam | 37(37) | ||

| Propofol | 36(36) | ||

| Remifentanil | 20(20) | ||

| Dexmedetomidine | 7(7) |

Characterization of the patients in the study.

X: average; SD: standard deviation; Me: median; IQR: interquartile range.

Source: Authors.

The grades with the Spanish version of the RASS in our study showed excellent reliability among the evaluators. The coefficient of intra-class correlation was “almost perfect”: 0.977 (CI 95% 0.968–0.984).

The qualitative concordance between the evaluators was also high with a kappa of 0.84 between the first and second evaluators, 0.85 between the first and third evaluators, and 0.86 between the second and third evaluators. Table 4 summarizes the grading of the three evaluators — Evaluator 1 (physician), Evaluator 2 (physician), Evaluator 3 (nurse) — and shows the respective concordance.

Concordance between 3 evaluators using the Spanish version of the RASS.

| Kappa | RASS Me(IQR) | Evaluator 1 | Evaluator 2 | Evaluator 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluator 1 | −3 (−4 to −1) | 1 | 0.84 | 0.851 |

| Evaluator 2 | −3 (−4 to −1) | 0.84 | 1 | |

| Evaluator 3 | −3 (−4 to −1.5) | 0.851 | 0.864 | 1 |

Me: median; IQR: interquartile range.

Source: Authors.

When we tend to a patient in the Critical Care Unit, physicians concentrate on protecting primary organs such as the heart and the brain as functional units, forgetting “the biological cost of the depression of consciousness” and the deleterious consequences of the alteration of the state of consciousness.19 Therefore, a rational model for the management of sedation in critical patients is vital, recognizing that it is not only a question of putting a patient to sleep to spare them suffering but of understanding all of the physiological and physio-pathological processes that are compromised when the functional state of the brain is altered with a sedative.20 In any scenario, be it in the operating room, in the post-anesthesia care room, or in the ICU, this model should be initiated without fail with a sensitive, objective, and validated evaluation of the patient's level of sedation.

In our country, one of the scales for objectively evaluating the level of sedation-agitation of critical patients is the RASS. Until now, this scale has not been translated to and validated in Spanish. The RASS has already been translated to other languages like French and Portuguese with satisfactory results.15,17

With these antecedents, a process in phases was carried out to translate and validate the scale in Spanish. This has resulted in a version that is conceptually equivalent to the original, is reproducible, and comprehensible to Spanish-speaking physicians. This new instrument features appropriate theoretical and psychometric support for its use, has adequate internal consistency and construct validity, like the original scale. In total consensus, the group of evaluators were well satisfied with and accepted the instrument. This study has notable advantages, namely the heterogeneous population — patients of medical, surgical, coronary and traumatic problems — to which the product was applied. It is also a project with a greater sample size and number of evaluations compared to similar studies with translation to other languages.

Upon analyzing the results, the kappa statistic showed a significant qualitative concordance with a result of 0.87 for an expected 0.80. The quantitative concordance among the evaluators, measures by CIC, was also excellent (0.97), showing that this new instrument, the RASS translated to Spanish, is valid, useful and precise for measuring the level of sedation by Spanish-speaking physicians in critically ill adult patients. As limitations of the study, we recognize the internal socio-cultural variability between the different regions of our country and external variability with other countries that also speak Spanish. A high adherence to sedation goals in critical patients in the participating institution meant an additional limitation in the validation process due to the absence of categories higher than 1 on the RASS in the results obtained.

Having access to a valid instrument specifically designed for measuring the level of sedation-agitation in Spanish will allow physicians to obtain reliable data, achieve real sedation goals, and avoid adverse consequences derived from not achieving these goals. This finished product is a proven tool for use not only in the clinical field but also in research contexts.

The Spanish version of the RASS shows an appropriate concordance with the original version in terms of validity, reliability, and applicability. This scale should be used systematically with all critical patients hospitalized in the ICU with the goal of reducing the negative impacts of overdosing and/or agitation.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FinancingThe authors did not receive sponsorship to carry out this article.

Please cite this article as: Rojas-Gambasica JA, Valencia-Moreno A, Nieto-Estrada VH, Méndez-Osorio P, Molano-Franco D, Jiménez-Quimbaya ÁT, et al. Validación transcultural y lingüística de la escala de sedación y agitación Richmond al español. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2016;44:216–221.