In this paper we provide evidence on the budgetary practice of 135 large firms located in Spain. The results have allowed us to evaluate a wide range of weakness attributed to the traditional budgeting approach, still called into question, as well as to discern towards what emerging paradigm budget is aligned the practice analyzed. Evidence shows that the budgetary approach used by the firms have managed to resolve many of the weakness imputed to the traditional budgeting. At the same time, we note that in the most of the cases studied these procedures are in line with the conceptual ideas defended by the Better Budgeting.

En este trabajo se ofrecen evidencias de la práctica presupuestaria de 135 empresas de gran tamaño localizadas en España. Los datos obtenidos nos han permitido evaluar un amplio abanico de deficiencias atribuidas al procedimiento presupuestario tradicional, aún hoy puestas en entredicho, así como vislumbrar hacia qué paradigma presupuestario emergente se alinea la práctica analizada. Los resultados obtenidos ponen de manifiesto que los procedimientos presupuestarios empleados por las empresas estudiadas solventan gran parte de las limitaciones atribuidas a la gestión presupuestaria tradicional. Al mismo tiempo observamos que en la mayor parte de los casos estudiasos dichos procedimientos se encuentran en línea con la propuesta conceptual del Better Budgeting.

Since mid twentieth century, the budgetary procedure traditionally held in the firms has been strongly questioned because of the numerous limitations attributed to it (Fernández & Rodríguez, 2011). This has led to part of the research to devote a great effort in proposing a new budgetary framework more in line with the productive context of the last decade, formed of an intense dialogue between research and practice (e.g., Hope & Fraser, 2004; Hansen & Torok, 2004; Gleich & Hofmann, 2005; Creelman, 2006; Horváth & Partners, 2007; Bogsnes, 2009; Morlidge & Player, 2009; Hope et al., 2011).

This innovative budgetary framework is located at the Consortium for Advanced Manufacturing International (CAM-I). Began to settle in the 90’s from two schools of thought clearly positioned, led by academics and business professionals, known as moderate school and renewal school (Rodríguez, 2010). But they have the same starting point; they share the premise that the traditional budget model is so outdated and inefficient.

Specifically, the moderate school comes from American research group -The US-based CAM-I Activity-Based Budgeting (ABB-gropup)-. This group defends the idea of evolution of the budgetary procedure based on: the development of new methodologies, the use of improved technical tools, and the application of principles of management. They suggest two lines of action: better budgeting and advanced budgeting.

The second, renewal school, formulated within the European research group -The European-based CAM-I Beyond Budgeting (BB-group)-, advocates for absolve to the firms of the budgetary procedure and replace it with a corporate culture based on flexible, adaptive and decentralized procedures. It has created a line of research, mainly raised from the professional field and from the Beyond Budgeting Round Table (BBRT), founded on the idea of conducting the business management free of budgeting, which is technically defined as beyond budgeting.

Although these management alternatives are accepted and recognized by the greater part of the business world, and the remarkable efforts being undertaken consultancies and organizations such as Horvath & Partners and the Beyond Budgeting Round Table (BBRT) for development and implementation, recent studies (e.g., Dugdale & Lyne, 2010; Libby & Lindsay, 2010) show that companies are still using a traditional budgeting, albeit with significant changes, and that some of the deficiencies attributed to has not been able to overcome.

From Umpaphaty (1987) to Dugdale & Lyne (2010) and Libby & Lindsay (2010), the results achieved by research on the budgetary practice (e.g., Ekholm & Wallin, 2000; Ahmad et al., 2003; Greiner, 2003; KPMG, 2004; CIMA-ICAEW, 2004; Durfee, 2006; Marginson et al., 2006) have shown homogeneity in recognizing the weaknesses of the traditional budget process, and that at most, from the direction of the companies are committed to an improved budgetary practices. However, heterogeneity has also been exhibited at the time to analyze the weaknesses reported in the literature.

In this study we carry out an exploratory analysis of the budgetary practice in 135 large companies located in Spain. By doing so and departing from previous literature, we provide evidence concerning the weaknesses attributed to the traditional budgetary procedure. Its implementation involved the preparation of a working framework structured on the basis of foregoing studies on: the conceptual status of budgeting research and the controversy of the traditional budgeting practices concerning the limitations of which it is accused and the conceptual alternatives to conventional budget management.

Results indicate that budgetary procedures implemented by the surveyed companies solve most of the limitations attributed to the traditional budgeting. They also reveal that a high percentage of cases studied betting on the better budgeting idea.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: the next section deals with the theoretical framework. The methodology used is provided in the third section. The fourth section sets out the results. Finally, the paper draws to a close with the main derivations.

Theoretical frameworkThe discontent of the business world with the traditional budgeting approach has led to senior executives and business leaders to accept a change in budgetary philosophy whose conceptual choices are oscillating from the development and implementation of innovative budgetary alternative to leave them without conditions (Creelman, 2006).

This change of philosophy requires to a new budgetary framework capable to ensuring the success of the different emerging ideological alternatives. The parameters on which it sits are precisely those critical factors that traditional budgetary framework has failed to overcome. We refer to:

- •

Promote the business plans from company’s strategic coherence.

- •

Link resource consumption to production volumes.

- •

Support continuous improvement and innovation.

- •

Develop and maintain a consistent behavior.

- •

Add value to the company while planning and budgeting.

Gleich & Hofmann (2005) state that this new budgetary framework is underpinned in the follows both ideological and methodological approaches:

- 1.

Simplify planning and budgeting.

- 2.

Guide both planning and budgeting to the output.

- 3.

Integrate and align both strategic and operational planning.

- 4.

Extend the planning and budgeting with nonmonetary magnitudes.

Reinvent budgeting, and therefore provide a framework according to the current management necessities involves the necessary migration of business towards a more adaptive and decentralized approach (Brander Brown & Atkinson, 2001; Daum, 2002; Hope & Fraser, 2004; Kaplan, 2009), and towards the adoption of budget practices and procedures redesigned, remodeled or reconstructed. In sum, the point is to build a theoretical and practical context that allows us to develop innovative dimensions of budget management.

Research has taken different courses of action that have derived in two schools of thought clearly defined, moderate school and renewal school, both linked to the Consortium for Advanced Manufacturing International (CAM -I), and the research groups Activity Based Budgeting -(ABB) group- and Beyond Budgeting -(BB) group-.

Under the moderate school, we can check for two lines of action as alternatives to the traditional budgetary management:

- •

Better budgeting. Initiative confined to a more flexible thinking than the traditional and submitted to the implementation of a set of autonomous and independent techniques with the aim of correcting the major number of deficiencies attributed to the conventional budgeting.

- •

Advanced budgeting. Advanced budgetary approach that streamlines the traditional budget functions, and at the same time supports the execution of business strategy according to a set of scientifically established management principles.

On the other hand, renewal school maintains that improvements or remodeling business budget process is not a final and comprehensive solution to the problems posed by the traditional budgeting approach, given that it enables the development of fixed performance contracts and the prevalence of centralized control. From this point of view, is firmly committed to the empowerment. As a solution it is proposed to manage without budgets applying the Beyond Budgeting approach, which focuses its interest in developing a holistic management model based on twelve managerial principles where coexists processes and innovative tools with the configuration of a new management style.

MethodThe present study is in the line of research set out in the work of Umapathy (1987), Ekholm & Wallin (2000), Ahmad et al. (2003), Greiner (2003), KPMG (2004), CIMA-ICAEW (2004), Marginson et al. (2006), Dugdale & Lyne (2010) and Libby & Lindsay (2010), whose objectives were oriented to describing the state of the art and the extent to which budgeting practices have evolved to meet the demands of the new context of production.

We took a four-phase methodological approach:

- 1)

Survey design.

- 2)

Population selection.

- 3)

Sample collection.

- 4)

Frequency analysis and clustering.

Published field work on the status of business budgeting practices (Umapathy, 1987; Ekholm & Wallin, 2000; Ahmad et al., 2003; Greiner, 2003; KPMG, 2004; CIMA-ICAEW, 2004; Durfee, 2006; Marginson et al., 2006) formed the basis for our data collection instrument, which we decided to organize into the following three conceptual layers:

- •

Issues relating to the firm’s strategy and to its relationship with budgeting procedures.

- •

Instrumental and situational issues relating to the budgeting system applied by the firm.

- •

Questions of management styles that represent alternatives to that of traditional budgeting.

Given the large number of indicators that we included initially to ensure completeness, we subjected them to a Delphi selection technique whereby we were able to reduce the number of errors, redundancies, and inconsistencies. The resulting pared down measurement instrument consisted of a 45-items questionnaire. Most of these items had closed responses on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 corresponding to “Strongly Disagree” and 7 to “Strongly Agree”, some had dichotomous responses, and some had responses on a nominal scale. The questionnaire was organized according to the conceptual strata defined above (see Appendix A).

PopulationFollowing Umapathy (1987), Ekholm & Wallin (2000), Greiner (2003), and KPMG (2004), we decided to analyze the status of budgeting practices in companies categorized as large firms. In particular, we applied the size criteria set out in the fourth corporate directive of the European Union (see the Official Journal of the European Union L-124, 20.5.2003), whereby a firm is considered large if it satisfies the following conditions:

- •

The number of employees exceeds 250.

- •

Billing exceeds 50millioneuros.

- •

Total assets exceed 43millioneuros.

We used the SABI database1 (Sistema de Análisis de Balances Ibéricos-System of Analysis of Balance Sheets of Iberia) to retrieve firms whose characteristics conformed to the above size stratum. Of the discriminating criteria available in this database, we decided to use the following:

- •

Firms whose productive activity takes place in Spain. SABI specifically includes around 1.1millionof such firms.

- •

Firms included in “La Clasificación Nacional de Actividades Económicas (The National Classification of Economic Activities) CNAE-93 Rev”.

- •

Firms with consolidated annual accounts.

- •

Firms with data on the number of employees, operating revenue, net sales, and total assets.

With the above selection criteria, and after adjusting the observation units initially retrieved from the database to account for such factors as the extinction of the firm, lack of contact details, entry into stages of bankruptcy proceedings, etc., the number of firms forming the study population amounted to 1176.

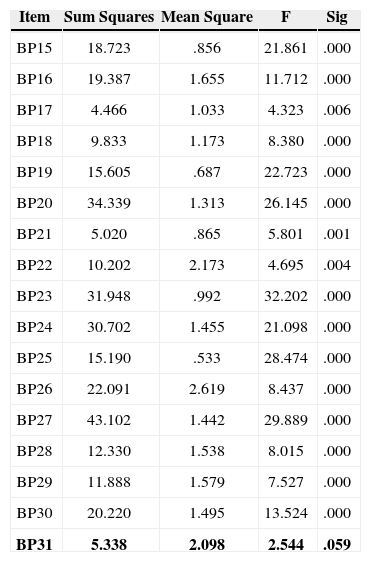

SampleThe special characteristics of the business world forced us to change our initially planned methodological strategy, which was to be one of stratified random sampling, to one of non-random sampling. This change of plans implied that an extra effort had to be made to contact all the firms constituting the study population, and to obtain a sample of firms based on the expectation of their greatest number of responses.

In particular, the questionnaire was e-mailed to the entire sample population after making telephone contact with the recipients. This involved a total of 1176 firms, with the respondents being mainly their Chief Financial Officers, Planning and Control Managers, or Controllers involved in their firm’s budgeting procedures. The data collection period was from October 2008 to February 2010.

In line with the methodological pattern of the study conducted by KPMG (2004) and Fortune FAQ Definitions and Explanations2, we considered it opportune to classify our population into strata based on annual operating income (table 1).

By the end of the data collection period, we had obtained 135 duly completed questionnaires for a response rate of 11.48% of the study population. The responses were organized into the strata defined in table 2. The survey’s technical data sheet is given in Appendix B.

Sample obtained*

| Stratum operating revenuemillion€/yr) | Population | Sample | n / N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | ||

| 50-250 | 717 | 60.97 | 38 | 28.15 | 5.30 |

| 251-500 | 206 | 17.52 | 17 | 12.59 | 8.52 |

| 501-1000 | 122 | 10.37 | 38 | 28.15 | 31.15 |

| 1001-2000 | 74 | 6.29 | 23 | 17.04 | 31.08 |

| 2001-5000 | 32 | 2.72 | 7 | 5.18 | 21.87 |

| >5000 | 25 | 2.12 | 12 | 8.88 | 48.00 |

| TOTAL | 1176 | 100.0 | 135 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

The statistical techniques applied to data, using the statistics program SPSS v. 19, were a frequency analysis and clustering. Frequency analysis were used to provide a means to know the distribution of the issues under study (see Appendix C). Hierachical and k-means clustering were applied as a pairwise statistical tool that is appropiate to organize objects into groups whose members are similar in some way. Hierarchical method was performed to define the number of clusters.

ResultsThe obtained data from the firms comprising the sample were analyzed according to:

- •

Content relating to the firm’s strategy and to the relationship between this strategy and the firm’s budgeting procedures.

- •

Instrumental and situational issues regarding the budgeting system that the firm applies.

- •

Questions relating to alternative management styles.

First off, we must begin by saying that the main types of strategy that the firms used (table 3) were found to be product leadership (with just over 52% of the cases), proximity to clients (44.6%), excellence in the production process (40.8%), and differentiation and competitive advantage (40%).

Categorization of the strategy type

| Strategy | Answers | % accumulated* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N° Strategy | % Strategy | ||

| Cost leadership | 25 | 8.7 | 19.2 |

| Market focus or segmentation | 32 | 11.1 | 24.6 |

| Differentiation and competitive advantage | 52 | 18.1 | 40.0 |

| Excellence of the production process | 53 | 18.4 | 40.8 |

| Proximity to clients | 58 | 20.1 | 44.6 |

| Product leadership | 68 | 23.6 | 52.3 |

| TOTAL | 288 | 100.0 | 221.5 |

A contingency analysis of these strategies provided a disaggregated vision of the weight that each of them had on the others (table 4). By way of example, of all the firms which primarily employ a product leadership strategy, 44.12% of them complement this action with the implementation of a strategy of proximity to clients, just over 42% with one of excellence in the production process, and nearly 40% with one of differentiation and competitive advantage. In this case as in the others, the principal strategies were accompanied by little complementary support from the strategies of cost leadership or of market focus and segmentation, reflecting the firms’ relative lack of confidence in these actions.

Contingency relationships of the strategies implemented by the firms of the sample*

| Strategy | Prod. Lead. | Cost Lead. | Diff. Adv. | Excell. | Prox. | Segment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prod. Lead. | 68 | 9 | 27 | 29 | 30 | 18 |

| % | 100.00 | 13.24 | 39.71 | 42.65 | 44.12 | 26.47 |

| Cost Lead. | 9 | 25 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 5 |

| % | 36 | 100 | 28 | 40 | 16 | 20 |

| Diff. Adv.. | 27 | 7 | 52 | 19 | 25 | 9 |

| % | 51.92 | 13.46 | 100.00 | 36.54 | 48.08 | 17.31 |

| Execell | 29 | 10 | 19 | 53 | 28 | 10 |

| % | 54.72 | 18.87 | 35.85 | 100.00 | 52.83 | 18.87 |

| Prox. | 30 | 4 | 25 | 28 | 58 | 12 |

| % | 51.72 | 6.90 | 43.10 | 48.28 | 100.00 | 20.69 |

| Segment. | 18 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 32 |

| % | 56.25 | 15.63 | 28.13 | 31.25 | 37.50 | 100.00 |

Frequency analysis results attained to examine the reciprocal relationship between strategy and the budgeting processes are displayed below:

- •

Most of the firms studied, the formulation of corporate strategy is to a greater or lesser extent linked to its budgeting system. This is reflected in an aggregate 79.7% agreement.

- •

By the same token, around 85% of firms surveyed agree, although to varying degrees, with the idea that budgets are instituted as an essential instrument for achieving the strategic objectives identified by management.

- •

In a clear consistency with previous result, 79.4% of the firms surveyed agreed with the idea that achieving strategic objectives has priority over any other goals. However, one notes that only 8.4% of the cases express this agreement categorically.

- •

One cannot generalize that the allocation of resources to departments is done solely and exclusively at the beginning of the budget period, much less that it remains constant throughout. Just 6% of the firms declare strong agreement with this idea, and 4.5% declare strong disagreement. There is a marked concentration of moderate and inconclusive responses around the central position, with 22.6% expressing complete neutrality on the question, and a certain balance between the non-extreme positions of agreement (36.8%) and disagreement (30%).

- •

Most firms surveyed (88.6%) reported carrying out regular reviews of their strategies, which leads us to think that they practice a process of continuous planning.

- •

The firms’ productive activity, as well as most of its executive and administrative actions, is aimed at the pursuit of strategic success. Although with varying degrees of intensity, 91% of the firms said that productive activity, together with the rest of the firm’s activities, has to be involved in attaining the established strategic objectives.

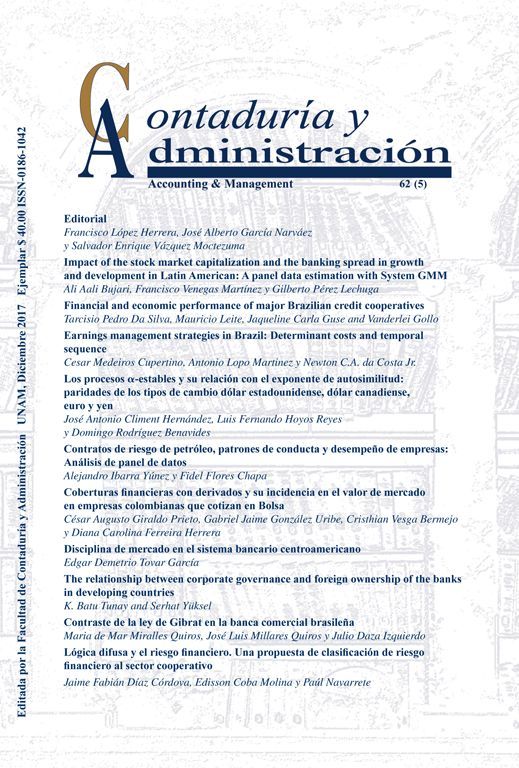

K-means analysis supports the results, as table 5 shows.

The ANOVA performed on the indicators in four clusters, supports the heterogeneity of the average values in each segment (table 6).

Analysis of the instrumental and situational aspects of the budgeting proceduresTo analyze the instrumental and situational aspects of the firms’ budgeting systems, we first needed to know the kind of budgeting procedures the responding firms relied on (table 7). As one observes in the table, the better budgeting system was by far the commonest alternative implemented (63.7%).

In contrast with the work of Ekholm & Wallin (2000), Ahmad et al. (2003), KPMG (2004), Lyne & Dugdale (2004), and Marginson et al. (2006) who found the traditional budgeting system to continue being the alternative that firms most commonly use, most of the firms in the present study reported taking as referent for their budgeting management the traditional approach but improved through the implementation of procedures designed to meet the demands of the competitive environment in which they operate.

It is also noteworthy in this regard that few firms (11.9%) applied Activity Based Budgeting systems. This is consistent with the findings of KPMG (2004) in which only 19% of the surveyed firms practiced this alternative system of budgeting. Very few of the firms surveyed (2.2%) implemented adaptive, decentralized, process-based budgeting (Beyond Budgeting).

Findings about the instrumental and situational aspects of the firms’ budgeting systems are as follows:

- •

Numerous international studies have revealed a degree of dissatisfaction of close to 80% of businesses with respect to their budgeting systems (e.g. Charan & Colvin, 1999; Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd., 2000; Neelyet al., 2001; Hunt, 2006; American Productivity & Quality Center, 2006). But for the firms of the present study, the pattern of responses was quite different, so much so that there was not a single case of strong dissatisfaction with their budgeting system, and only about 11% expressed moderate or slight dissatisfaction, while 69.7% responded with some degree of satisfaction.

- •

This is significantly different from one of the conclusions reached by KPMG (2004) in which 35% of the firms studied with billing exceeding fivemilliondollars showed some level of dissatisfaction with their budgeting processes. Since our study was performed with firms with billing volumes well above the range used by KPMG as a discriminating criterion for their sample, the result is even more striking.

- •

We concur with Libby & Lindsay (2010) in that it is impossible to draw a reliable conclusion about whether or not changes in the firms environment may invalidate established budgets. Only 3% of the firms studied considered categorically that budgets remain effective when faced with actual or potential changes in the environment, compared with 3.7% who took the opposite position.

- •

Coinciding with Greiner (2003) who found that 71% of the surveyed firms reported the budgeting process to be an important management tool, most of the firms in the present study (83.7%) see the budget as a management tool which has become more important in recent years. In particular, 60% responded with moderate or total agreement.

- •

Although a significant proportion of the respondent firms (21.5%) did not take a definite position one way or the other regarding the predominance of budgets over other management tools, 68.9% of them did agree to some degree with this statement.

- •

Linked to the importance of the budgeting process for a firm’s system of corporate governance, a significant number of respondents (83.8%) expressed agreement that the budgeting system practiced in their firm contributed value to its management.

- •

Given that most of the firms were applying better budgeting practices and the aforementioned increasing preponderance of budgeting processes over other instruments of corporate management, it was completely coherent to find that 62.7% of the respondents did not see their budgeting systems as obsolete, with another 23.1% not declaring either way on the question.

- •

The data showed that budget objectives were not always met (6.8%). although by far most of the firms (73.7%) said, with different degrees of emphasis. that in general they were achieved.

- •

With respect to the process of budgeting, the firms presented a considerable division of opinions. While 40.3% agreed with the statement of the item that their budgets were constructed by extrapolating from previous years, 41% expressed the contrary opinion. We conclude therefore that there are two opposing perceptions of the construction of budgets. While some years ago the commonest inclination in this regard was towards the preparation of budgets based on historical data (e.g. Umapathy, 1987), one might say now that perhaps the evolution that has taken place in budgeting has changed the way that many firms deal with this process.

- •

As in Greiner (2003), our results show that the management of most of the firms surveyed (68.9%) are to some degree in agreement about using the budget as a mechanism of control of the performance of the firm’s personnel.

- •

For a high proportion of the respondent firms (78.5%). the incentive system is to a greater or lesser extent conditioned by meeting budgeted targets.

- •

Most of the respondents, essentially from a moderate and strong perspective, agreed that management is not only actively engaged in the elaboration of budgets. but also in monitoring the corresponding actions and following up the ultimate attainment of the goals.

- •

Usually, various revisions and updates are made to budgets during the fiscal year. Specifically, with moderate (30.6%) and categorical (26.1%) positions prevailing, 74.6% of the firm state that they adjust their budgets several times a year. This is consistent with the findings of Umapathy (1987), KPMG (2004), American Productivity & Quality Center (2006) and Player (2009) of a clear tendency for firms to perform regular reviews of budgeted goals, and make periodic changes to the budgets themselves when presumed necessary.

- •

There was a marked difference of opinion regarding the time spent in budgeting and its possible implications in terms of bureaucracy and costs. Unlike the results reported by Ekholm & Wallin (2000) and KPMG (2004) that approximately 90% or 84%. Respectively, of firms required on average more than two months to prepare budgets, just over 41% of the firms of the present survey were not in agreement with the statement that budgeting consumes excessive time and is tediously bureaucratic and costly. In contrast, only 15% of them were in moderate to full agreement with the statement.

- •

For most of the respondents (75.6%), budgeting does not encourage negotiating practices or unethical conduct among the firm’s managers. nor among its different areas of activity. It is noteworthy that not a single respondent expressed strong agreement with the statement, although there was some milder degree of agreement (14.1%), suggesting that in these relatively few cases the budgeting process may give rise to negotiations and unethical behavior among their firm’s managers and the departments they run.

- •

Coherent with the previous finding, too more than 65% of the firms surveyed expressed a greater or lesser extent of disagreement with the statement that budgeting systematically favors a vertical hierarchy management style, which would hinder knowledge sharing and the active participation of staff. It is noteworthy that 19.3% of the cases took a neutral stance on the item.

- •

Mainly expressing an opinion of moderate disagreement, most of the firms surveyed (67.4%) did not find that budgets induce the creation of departmental barriers. Instead, their approach is one of shared knowledge that allows rapid reaction to the constantly changing environment. Indeed, only 4.4% of the respondents expressed moderate or complete agreement with the statement.

- •

Only 3% of the firms declared their budgeting to be unquestionably oriented to minimizing costs, and at the other end of the scale only 4.5% expressed strong disagreement with this notion. The dispersion of responses among moderately positive and moderately negative positions suggests that most of the firms surveyed take, together with cost reduction, other objectives into account in budgeting.

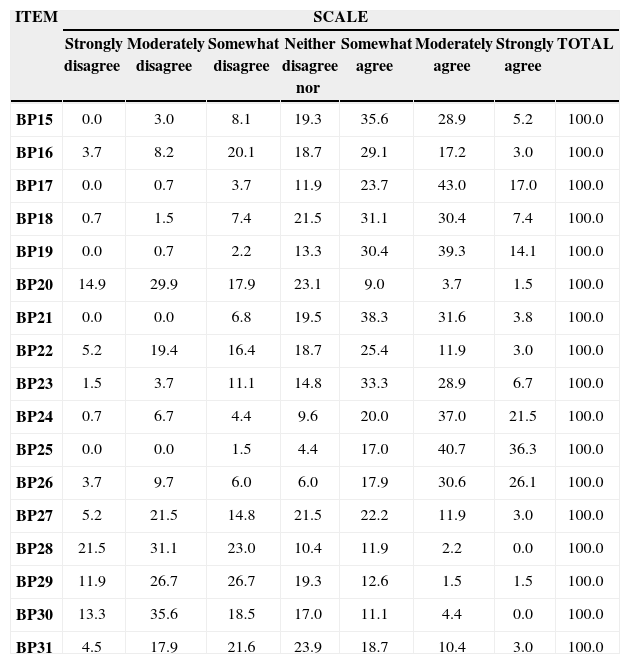

Again, K-means analysis supports the findings, as table 8 demonstrates.

K-means clustering for items BP15-BP31 and relative size

| Item | Cluster | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| BP15 | 5.77 | 5.29 | 4.56 | 3.50 |

| BP16 | 5.00 | 4.86 | 3.92 | 2.70 |

| BP17 | 5.77 | 5.48 | 5.65 | 4.50 |

| BP18 | 5.31 | 5.10 | 5.06 | 3.40 |

| BP19 | 6.11 | 5.81 | 5.29 | 3.80 |

| BP20 | 2.00 | 2.14 | 3.66 | 4.60 |

| BP21 | 5.60 | 4.90 | 4.92 | 4.50 |

| BP22 | 4.34 | 2.95 | 3.89 | 4.60 |

| BP23 | 5.74 | 3.38 | 5.02 | 3.40 |

| BP24 | 6.06 | 4.38 | 5.61 | 3.10 |

| BP25 | 6.69 | 5.86 | 6.03 | 4.30 |

| BP26 | 4.31 | 6.24 | 5.56 | 4.30 |

| BP27 | 2.74 | 2.62 | 4.79 | 3.90 |

| BP28 | 2.20 | 1.90 | 2.94 | 3.80 |

| BP29 | 2.66 | 2.24 | 3.56 | 3.10 |

| BP30 | 2.20 | 2.05 | 3.56 | 3.20 |

| BP31 | 3.80 | 3.19 | 4.13 | 3.40 |

| N (firms) | 35 | 21 | 62 | 10 |

| Relative Size (%) | 27.35 | 16.41 | 48.4 | 7.8 |

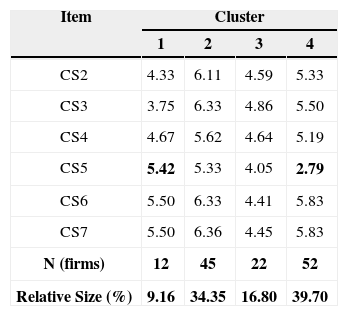

The ANOVA performed on the indicators in this conceptual section showed the heterogeneity of the average values in each segment except in the case which analyzes whether the implementation of the budgets are primarily intended to reduce costs (see table 9).

Instrumental and situational aspects of the firms’ budgeting systems (ANOVA)

| Item | Sum Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP15 | 18.723 | .856 | 21.861 | .000 |

| BP16 | 19.387 | 1.655 | 11.712 | .000 |

| BP17 | 4.466 | 1.033 | 4.323 | .006 |

| BP18 | 9.833 | 1.173 | 8.380 | .000 |

| BP19 | 15.605 | .687 | 22.723 | .000 |

| BP20 | 34.339 | 1.313 | 26.145 | .000 |

| BP21 | 5.020 | .865 | 5.801 | .001 |

| BP22 | 10.202 | 2.173 | 4.695 | .004 |

| BP23 | 31.948 | .992 | 32.202 | .000 |

| BP24 | 30.702 | 1.455 | 21.098 | .000 |

| BP25 | 15.190 | .533 | 28.474 | .000 |

| BP26 | 22.091 | 2.619 | 8.437 | .000 |

| BP27 | 43.102 | 1.442 | 29.889 | .000 |

| BP28 | 12.330 | 1.538 | 8.015 | .000 |

| BP29 | 11.888 | 1.579 | 7.527 | .000 |

| BP30 | 20.220 | 1.495 | 13.524 | .000 |

| BP31 | 5.338 | 2.098 | 2.544 | .059 |

The third and last layer of concepts that we examined to complete the study was aimed at determining the different management styles that the firms tacitly or explicitly employ, and their relationship with budgeting practices. Findings are showed as follow.

- •

The prevalent responses reflected that the setting of fixed corporate goals which are negotiated internally, rather than setting budget targets based on benchmarking. Percentagewise, 63.7% of the respondent firms set their targets by means of a process of negotiation, and maintain them unchanged throughout the fiscal year. At the other ends of the scale, of the 18.5% of the firms who agree with the statement that they use relative goals in budgeting, only 5.2% express this agreement moderately or strongly.

- •

The incentive scheme that the surveyed firms implement is not determined by relative success, as is reflected by the responses expressing disagreement (56.4%). The data reflect an emphasis on the use of incentive systems based on reaching pre-set targets that have been negotiated internally. There was a major proportion of responses (22.6%) expressing uncertainty on this issue, and a small proportion (6%), again similar to the previous finding, expressing either moderate or strong agreement that their incentives are based on relative success.

- •

Information showed that the style of management of 66.2% of the firms studied includes a practical approach to planning. This involves granting certain powers to lower-level corporate officers. Nonetheless, only 4.5% of the firms strongly agreed that they followed this approach, and 21.1% took a neutral position on the question.

- •

Although not entirely conclusive, on aggregate most of the firms declared that they allocate resources according to demand. In particular, except in the proportion of responses (20.7%) expressing a neutral position on how resources are allocated to the subunits of the firm. 63.7% of the respondent state that resources are assigned as they are needed. In contrast, only few of the firms surveyed (15.6%) practice a rigid form of allocation, although even then this is with a certain qualification since no response expressed this opinion strongly.

- •

Another aspect that emerged from the data was the clear predominance of the practical exercise of a management style based on the dynamic coordination of the firm’s actions aimed at better satisfying customer demand. Disaggregating the data, one observes that 72.7% of the firms offer their clients to a greater or lesser extent customized solutions and the capacity for timely attention and response.

Moreover, the fact that no firm expressed strong disagreement with the statement and that somewhat fewer than 14% did so only moderately or slightly leads one to conclude that the trend, not just for these firms, but also possibly for others of similar characteristics on this issue is to apply a style of management that takes the client as the prime referent.

- •

Stand out both the major proportion of firms (29.3%) taking an indeterminate position regarding the exercise of budget control based on effective governance3 and the small proportion who say they follow this approach in its entirety. Given this scenario and the dispersion of opinions on the issue, we conclude that either the true sense of the content of the question was not understood, or there is still a long way to go in developing the field of self-management.

- •

Data showed a noticeable impulse towards a management style based on training and support. It has been demonstrated in experiences in other business contexts (e.g., Hope & Fraser, 2004; Hope, 2006; Bogsnes, 2009) that employees of such firms gain competences in the concepts of collaboration and shared values.

- •

One notes a clear commitment by the practice of a culture of responsibility that involves all the personnel of the firm. The recognition of a high-performance climate based on relative success and constant challenges for employees implies the delegation of authority to all corporate levels, in which the transfer of information between agents with responsibility and the centers of activity has to be a key.

Proof of this is that, while 26.1% of the respondents do not come down on one side or the other of the question, and 12.7% express disagreement, the majority (61.2%) stated either strongly (6.7%) or at least moderately and slightly (54.6%) that their firms promote a climate of high performance that has the capacity to develop employees’ skills. Nevertheless, one must bear in mind that this circumstance was not found to hold for the implementation of incentive systems based on relative targets, so that one might deduce that this trend towards a climate of high performance based on relative success is still in its infancy.

- •

Linked to the above, we observed that 66.7% of the firms involve their personnel in the implementation of the firm’s strategy, conferring to a greater or lesser extent authority on all levels of responsibility (empowerment). There stands out the fact that no firm expressed strong reluctance to promote a culture of responsibility under which its personnel would be able to develop their skills and commitment.

- •

Paradoxically, it seems that in the current business context there is no generalized major empowerment of the lower corporate level managers and employees. Specifically, the data reflected a fairly equal distribution of attitudes in this regard. In particular. 32.1% were not in agreement with the further empowerment of those with responsibilities at lower hierarchical levels. 19.4% took a neutral position, and 48.4% were in favour of conferring such authority, although even then most of them (32.8%) only expressed slight agreement with the idea. All this again confirms that there is still a long way to go to reach the levels required by avant-garde budgeting practices based on effective governance and a culture of responsibility.

- •

It is considered very similar aspects of the firms’ management styles, and indeed their responses showed similar distributions. The plurality of systems and technical tools for handling information that one had traditionally been accustomed to encountering made proliferation of dishonest actions on the part of staff, such as concealment or distortion of information, more likely. Here, however, one notes that most of the firms surveyed (86.7%) promote a cooperative attitude among their employees. both individually and collectively, and most of them (81.5%) also express a clear willingness to promote and defend a single, ethical and open. system of information.

- •

Of the total set of firms studied, 53% formalized with more or less rigor a map of activities for each of the centers into which it is organized in order to improve its budgeting management. However, only 15.6% did so in a rigorous form. There stands out, however, that 24.2% came down on neither one side nor the other of the issue.

- •

While 49.2% of the respondent firms partially implement a process of analysis and elimination of activities that are not needed to add value for their clients only 5.3% strongly declare that they screen for and eliminate superfluous activities.

- •

Considered together these last two findings, it is observed that, even though the great majority of the firms surveyed have not implemented comprehensive Activity Based Budgeting (see Table 7), they do to some extent control certain activities they deem transcendent for the attainment of their objectives.

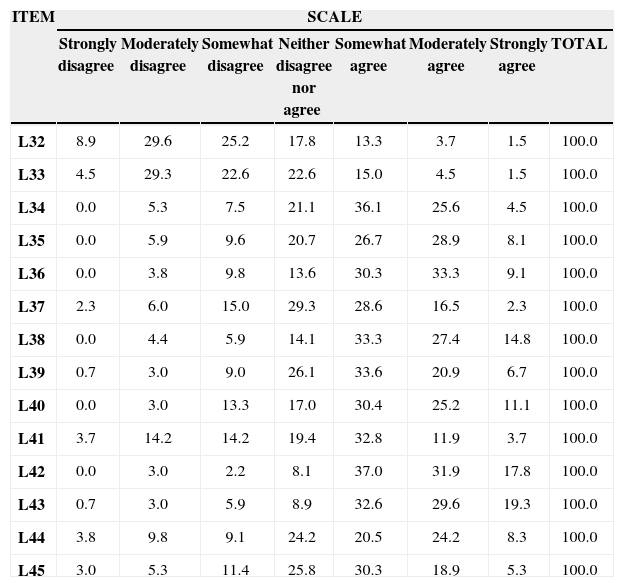

Once more, the K-means analysis supports these findings (see table 10).

K-means clustering for items L32-L45 and relative size

| Item | Cluster | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| L32 | 3.98 | 3.36 | 2.82 | 2.18 |

| L33 | 3.68 | 3.79 | 2.91 | 2.74 |

| L34 | 4.76 | 5.71 | 3.82 | 4.82 |

| L35 | 4.98 | 5.71 | 3.64 | 4.68 |

| L36 | 5.34 | 5.50 | 3.55 | 5.15 |

| L37 | 4.51 | 5.25 | 3.27 | 4.03 |

| L38 | 4.83 | 6.36 | 3.55 | 5.41 |

| L39 | 4.66 | 6.18 | 3.64 | 4.38 |

| L40 | 4.85 | 6.39 | 3.36 | 4.68 |

| L41 | 4.56 | 5.21 | 2.73 | 3.50 |

| L42 | 5.24 | 6.43 | 4.23 | 5.50 |

| L43 | 5.17 | 6.32 | 4.00 | 5.53 |

| L44 | 3.76 | 5.39 | 3.32 | 5.65 |

| L45 | 4.29 | 5.36 | 2.73 | 5.21 |

| N (firms) | 41 | 28 | 22 | 34 |

| Relative Size (%) | 32.80 | 22.4 | 17.6 | 27.2 |

The ANOVA for this set of items again reflects heterogeneity in the mean values of each cluster (see table 11).

Repercussions of the management style in the budgeting process (ANOVA)

| Item | Sum Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L32 | 21.263 | 1.336 | 15.919 | .000 |

| L33 | 8.935 | 1.488 | 6.005 | .001 |

| L34 | 14.880 | 1.021 | 14.580 | .000 |

| L35 | 18.302 | 1.382 | 13.243 | .000 |

| L36 | 19.684 | 1.123 | 17.521 | .000 |

| L37 | 17.575 | 1.147 | 15.318 | .000 |

| L38 | 34.575 | .793 | 43.614 | .000 |

| L39 | 29.787 | .764 | 38.987 | .000 |

| L40 | 38.700 | .747 | 51.838 | .000 |

| L41 | 32.391 | 1.402 | 23.099 | .000 |

| L42 | 20.406 | .800 | 25.512 | .000 |

| L43 | 22.939 | 1.061 | 21.620 | .000 |

| L44 | 40.008 | 1.626 | 24.601 | .000 |

| L45 | 36.136 | 1.048 | 34.473 | .000 |

In addition to the previous findings, we performed a posteriori characterization of the firms’ composition of each cluster identified, by sector, by turnover, and by budgetary process implemented.

Among the most significant results, stand out that the sectors of activity which have greater weight when assessing the relationship between strategy and budgetary system, as well as the instrumental and situational aspects of the budgeting procedures and the repercussions of management style in the budgeting process were, in this order, manufacturing, real estate activities and trade.

On the other hand, stand out that the turnover of these companies range from one billion Euros and two thousand. Specifically, it notes that the assess of the relationship between corporate strategy and budget system, as well as about the impact of management style in the budgetary process, brings together the firms with turnover of less than one billion Euros. Similarly, the analysis of instrumental and situational aspects of the budgetary procedure in each segment brings together firms with revenues less than or equal to two billion Euros.

Finally, clustered firms reveal the predominance of better budgeting system in relation to others procedures such as Traditional Budgeting, Activity Based Budgeting or even Beyond Budgeting. Nevertheless, Traditional Budgeting still has a significant presence in the analyzed firms.

Summary and ConclusionsThe aim of the present study has been to analyze the status of budgeting practice in Spain, particularized to the firms of greatest strategic capacity. Taking a representative sample of firms and analyzing statistically the information they provided during the period October 2008–February 2010, we verified that in Spain, for this set of firms and as will also be the case for those of similar characteristics, budgeting practices have evolved away from the traditional conception.

Specifically, we observed that, contrary to part of the international research literature (e.g., Kaplan & Norton, 2001; Hope & Fraser, 2003; Horváth & Sauter, 2004; Pierre, 2007) which describes a general lack of alignment between plans of operational action and the corporate strategies that firms define, the firms of the present study express an appropriate linkage between their budgeting actions and the strategy set by top management.

The main reason for this is that most of the participating firms consider budgets to be an essential management tool in achieving their strategic objectives. Indeed, this is so much so that, in their management’s view, to be able to withstand the convulsions occurring in the new context of production they are facing, all the tasks their organizations carry out should be involved in achieving this mission.

To this end, they consider it necessary to transmit to those involved in the firm’s processes that strategically planned targets have priority above any other goal or interest whether individual or departmental, and that it is fundamental to direct the mentality of all levels of management towards the continual updating of corporate strategy.

Empirical evidence shows that corporate strategy must be seen as the determining factor towards which budgetary management must be geared. At least for the set of firms studied and for those of similar characteristics, strategic planning and the budgeting process that derives from it must be closely linked and interconnected. In this respect we agree with Libby & Lindsay (2010) who concluded that criticisms of linkages between strategy and budgets had no basis for the firms which they analyzed, in as much as most of them made use of the budgeting procedure to foster a corporate strategy oriented attitude.

Concerning to the instrumental and situational issues involved in the budgeting process, the respondent firms were observed to have evolved towards a more advanced budgeting framework.

Our study has shown a significant level of satisfaction with current budgeting practices, as well as a degree of excellence of those practices which stands out above that of most other management tools.

The views expressed by the agents consulted in this regard refer to current budgeting procedures in their firms being dynamic and effective in character, while comprehensively contributing to creating value for management. This leads us to conclude that the budgeting systematic being practiced have the sufficient capacity to meet today’s competitive and demanding business environment.

Indeed, this is so much so that, with far more intensity and confidence than just a few years ago, firms are reviewing and updating their budgeting performance. In fact even several times within the same fiscal year. This is in line with the findings of Libby & Lindsay (2010) that most of the firms they studied modify their budgets to mitigate the effects that changes in the environment might have, whether on individual or corporate performance, or on the company’s results.

Also striking (even though it is true that budgets in general continue to be used as an instrument of control over staff performance, that incentives are conditioned by compliance with budgeted targets, and that management is actively involved in the preparation and monitoring of budgeting actions) was that the information revealed that the levels of negotiation and not too ethical behavior were really very low, and that there were instead high levels of participation and cooperation.

This maybe because we only had the views of one of the parts involved (senior management). It would be desirable, therefore, for future studies to gather information on these matters from all the parties involved, located throughout the corporate hierarchy.

As a general conclusion, we could state that some of the criticisms leveled at budgeting systems in recent years, pointing to their limitations or failures, have been corrected or smoothed over in the firms constituting our study, or at least they are either not perceived or those responsible for their implementation may not want to recognize them. Indeed, satisfaction with budgeting processes, the importance those firms attach to budgeting systems, the contribution of these systems to value in the firm, keeping the information contained in the budgets up-to-date, and the increase in cooperation and shared knowledge are in line with the goals expressed in some of the literature studies that we reviewed, and clearly represent an improvement over some of the scientific experiences they described.

Nonetheless, there was also confirmation of certain of the deficiencies attributed to budgeting practices. Examples were the significant proportion of firms (40.3%) still configuring their budgets by extrapolating from previous years. the high proportion of cases (78.5%) which tie their incentives to meeting the targets set out in the budgets, and the excessive level (93.3%) of management intervention in the actions carried out by the firms’ personnel and in whether or not they have attained the targets set out in the budgets.

Focusing finally on the analysis of the content related to the new budgeting framework, we observed some management actions that are in line with the budgeting approach demanded by today’s competitive reality. There stands out the commitment to an ever greater empowerment of the firm’s different levels of responsibility, characterized by granting working teams at lower hierarchical levels the authority to initiate improvements, and by fostering a general culture of responsibility in the firm. Another aspect of management style in this sense is the orientation of the firm’s functions towards the demands of its clients rather than towards internal processes, thereby encouraging more dynamic and effective customer management. There also stand out the form in which firms are allocating resources, mostly in a more rational and flexible way, and the effort being made to foster a management style that is based on training and support.

Notwithstanding these advances, one has to be wary of being too optimistic, since budgeting goals are still being set on the basis of internal negotiation, incentive systems are still being tied to those objectives, and personnel performance is still subject to overly rigorous control. These aspects clash with some of the premises underpinning the budgeting framework that current trends seem to be moving towards.

| POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS | Firms of major strategic capacity Number of employees>250 Operating revenue>€50millionTotal Assets>€45million |

|---|---|

| POPULATION | 1176 |

| GEOGRAPHICAL SCOPE | National |

| DATA COLLECTION METHOD | Digital survey following prior contact by telephone and e-mail |

| SAMPLE AGENTS | Company managers. Preferentially CFOs. Planning and Control Managers, and Controllers directly involved in the budgeting process |

| SAMPLE SIZE | 135 |

| SAMPLING ERROR | 7.94%4 |

| CONFIDENCE LEVEL | 95% |

| SAMPLING PROCEDURE | The questionnaire was sent to all firms comprising the population |

| PERIOD OF FIELD WORK | October 2008 - February 2010 |

k takes the value 1.96 for a 95% confidence level; P=Q=0.5, i.e., it is assumed that occurrences and non-occurrences are equally likely; N is the total population (universe), which in our case was 1176 firms; n is the number of responses (duly completed questionnaires), which in our case was 135 firms.

Indicators measuring the relationship between corporate strategy and budgeting process*

| ITEM | SCALE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Moderately disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neither disagree nor agree | Somewhat agree | Moderately agree | Strongly agree | TOTAL | |

| CS2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 19.5 | 30.1 | 38.3 | 11.3 | 100.0 |

| CS3 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 29.3 | 35.3 | 20.3 | 100.0 |

| CS4 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 16.8 | 42.0 | 29.0 | 8.4 | 100.0 |

| CS5 | 4.5 | 10.5 | 19.3 | 22.6 | 24.8 | 12.0 | 6.0 | 100.0 |

| CS6 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 8.3 | 28.0 | 32.6 | 28.0 | 100.0 |

| CS7 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 6.0 | 28.6 | 36.1 | 26.3 | 100.0 |

Indicators measuring the instrumental and situational aspects of the budgeting process*

| ITEM | SCALE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Moderately disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neither disagree nor | Somewhat agree | Moderately agree | Strongly agree | TOTAL | |

| BP15 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 8.1 | 19.3 | 35.6 | 28.9 | 5.2 | 100.0 |

| BP16 | 3.7 | 8.2 | 20.1 | 18.7 | 29.1 | 17.2 | 3.0 | 100.0 |

| BP17 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 3.7 | 11.9 | 23.7 | 43.0 | 17.0 | 100.0 |

| BP18 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 7.4 | 21.5 | 31.1 | 30.4 | 7.4 | 100.0 |

| BP19 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 13.3 | 30.4 | 39.3 | 14.1 | 100.0 |

| BP20 | 14.9 | 29.9 | 17.9 | 23.1 | 9.0 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 100.0 |

| BP21 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 19.5 | 38.3 | 31.6 | 3.8 | 100.0 |

| BP22 | 5.2 | 19.4 | 16.4 | 18.7 | 25.4 | 11.9 | 3.0 | 100.0 |

| BP23 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 11.1 | 14.8 | 33.3 | 28.9 | 6.7 | 100.0 |

| BP24 | 0.7 | 6.7 | 4.4 | 9.6 | 20.0 | 37.0 | 21.5 | 100.0 |

| BP25 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 4.4 | 17.0 | 40.7 | 36.3 | 100.0 |

| BP26 | 3.7 | 9.7 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 17.9 | 30.6 | 26.1 | 100.0 |

| BP27 | 5.2 | 21.5 | 14.8 | 21.5 | 22.2 | 11.9 | 3.0 | 100.0 |

| BP28 | 21.5 | 31.1 | 23.0 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| BP29 | 11.9 | 26.7 | 26.7 | 19.3 | 12.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 100.0 |

| BP30 | 13.3 | 35.6 | 18.5 | 17.0 | 11.1 | 4.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| BP31 | 4.5 | 17.9 | 21.6 | 23.9 | 18.7 | 10.4 | 3.0 | 100.0 |

Indicators designed to observe the management styles applied in response to the new budgeting context*

| ITEM | SCALE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Moderately disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neither disagree nor agree | Somewhat agree | Moderately agree | Strongly agree | TOTAL | |

| L32 | 8.9 | 29.6 | 25.2 | 17.8 | 13.3 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 100.0 |

| L33 | 4.5 | 29.3 | 22.6 | 22.6 | 15.0 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 100.0 |

| L34 | 0.0 | 5.3 | 7.5 | 21.1 | 36.1 | 25.6 | 4.5 | 100.0 |

| L35 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 9.6 | 20.7 | 26.7 | 28.9 | 8.1 | 100.0 |

| L36 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 9.8 | 13.6 | 30.3 | 33.3 | 9.1 | 100.0 |

| L37 | 2.3 | 6.0 | 15.0 | 29.3 | 28.6 | 16.5 | 2.3 | 100.0 |

| L38 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 5.9 | 14.1 | 33.3 | 27.4 | 14.8 | 100.0 |

| L39 | 0.7 | 3.0 | 9.0 | 26.1 | 33.6 | 20.9 | 6.7 | 100.0 |

| L40 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 13.3 | 17.0 | 30.4 | 25.2 | 11.1 | 100.0 |

| L41 | 3.7 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 19.4 | 32.8 | 11.9 | 3.7 | 100.0 |

| L42 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 8.1 | 37.0 | 31.9 | 17.8 | 100.0 |

| L43 | 0.7 | 3.0 | 5.9 | 8.9 | 32.6 | 29.6 | 19.3 | 100.0 |

| L44 | 3.8 | 9.8 | 9.1 | 24.2 | 20.5 | 24.2 | 8.3 | 100.0 |

| L45 | 3.0 | 5.3 | 11.4 | 25.8 | 30.3 | 18.9 | 5.3 | 100.0 |

An economic and financial database that includes more than onemillionSpanish and more than three hundred thousand Portuguese firms.