Capitalism has promoted and requires the growing knowledge of entrepreneurs, creative people who have the ability to solve problems in the form of innovation. The types of enterprises they create can be social, public and private. By creating an enterprising company new products and new production methods can be introduced, new markets are open, new sources of raw materials and inputs are developed and new market structures in an industry are created. Entrepreneurship can be taught, the question is how to do it. Teaching entrepreneurship should go beyond the business plan. It proposes a form that overcomes the mistakes found by the author in two research studies in 2008 and 2014 in the programs of management in Bogotá.

El capitalismo ha promovido y requiere el conocimiento cada vez mayor de los empresarios, la gente creativa que tienen la capacidad de resolver problemas en forma de innovación. Los tipos de empresas que crean pueden ser sociales, públicos y privados. Mediante la creación de una empresa emprendedora nuevos productos y nuevos métodos de producción pueden ser introducidas, nuevos mercados están abiertos, nuevas fuentes de materias primas e insumos se desarrollan y nuevas estructuras de mercado en una industria se crean. El emprendimiento se puede enseñar, la pregunta es cómo hacerlo. La enseñanza del espíritu empresarial debe ir más allá del plan de negocios. Propone una forma que supere los errores encontrados por el autor en dos estudios de investigación en 2008 y 2014 en los programas de gestión en Bogotá.

Education is a prerequisite for raising productivity in all economic sectors, and a critical instrument in the framework of a productive development policy. There are not enough ways for education systems to respond quickly to the needs of the productive sector in the world. According to the Global Competitiveness Index, no country in Latin America is known for this aspect, Costa Rica is ranked 48 and Colombia has fallen 26 places in the rank of health and primary education – position 105 in the world. In the rank of Higher education Chile is in the 32nd place, Costa Rica in the 37th, Brazil at 41 and Colombia is in the 69th, far from South Korea – 23rd – and Malaysia – 46th. In coverage rates in higher education Chile covers up to 75% and Uruguay 65% making progress in the first decade of the millennium, while Colombia shows a 45% coverage that is expected to expand to a 64% in 2018, far from the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries average – about 83% in 2012 (Consejo Privado de Competitividad, 2014).

In the past an increasing number of entrepreneurial initiatives were undertaken across the globe during the technology boom of 1999–2001. Such initiatives also fueled the take up of technology: “without the action of these entrepreneurs, oriented by a specific set of values, there would be no new economy and the Internet would have diffused at a much slower pace and with a different range of applications” (Castells, 2001a,b).

There are not recipes or unique objectives in Latin America: entrepreneurial activities aim for regional development, employment generation, development of SMEs and the promotion of innovative activity (BID, 2004, pp. 265). The lack of education in entrepreneurship in Spain has made 80% of the new businesses to fail within the first five years of creation, in the United States, companies have an average life of six years, while 30% will not meet its third year. In Latin America the situation is similar: in Argentina only 7% of the enterprises reach the second year of life; in Chile, 25% of companies disappear in the first year (Velázquez Valadez, 2008). In Mexico 75% of the new businesses close after two years of operations, and between April 2009 and May 2012, for every one hundred existing establishments, 20 of them closed and 20 initiated activities, approximately. Delving into this data we see that the INEGI shows that in this period (2009–2012) 1,135,089 establishments were born and that the sector that had the highest proportion of births was the private non-financial services, with a 30.7%, followed by the commercial sector with a 28.4% and, thirdly, the manufacturing industries with a 20.4%. Regarding the closure of establishments (884.240), the worst sectors were trade, services and manufacturing industries, with 22.9%, 22.7% and 16.7%, respectively, so if we perform a comprehensive and comparative analysis of the various situations, we can see that the main causes of failure are in the area of finance and administration, 40% and 34% respectively. It is noteworthy that the percentages do not add up to a 100% because the causes of failure are not mutually exclusive. (INEGI, 2013).

In Bogotá-Colombia, an exploratory study was made with 43 higher education institutions with administration programs in 2008. The results showed that 81% of the studied institutions had in its formal documents “entrepreneurship” in their educational programs. 33% of the universities includes entrepreneurship in the professional profile of its graduates, 23% in the introduction of their administration program and 23% in their program objectives, 17% in their occupational profile and 9% defines it as a professional competence. Developing entrepreneurship spaces is a task that belongs to administration faculties (27%), to entrepreneurship centers, business development and business creation areas (18%) and to business administration programs (13%). Entrepreneur strategies are taught in the undergraduate programs (74%) through lectures (89%). Other strategies include company visits (80%). Entrepreneurship is promoted through exhibitions (75%), lectures and competitions (Herrera & Ortiz, 2010). In 2013, another research about teaching entrepreneurship was made; this one was with business administration graduates that started their own businesses. The research sought for the impact of having had entrepreneurship lectures during the undergraduate program, and found that 48% of the entrepreneurs attributed to their family environment their tendency to start a company, 24% consider that emerged from previous jobs where they acquired experience and knowledge, 16% attributed their impulse to some teachers of the program and 12% created their businesses because they were unemployed. The companies created between 1999 and 2012; belong in the secondary sector industry (12%) and in the tertiary sector industry (88%). New businesses are micro (64%) and small (36%) and generated jobs. Only 11 companies have had increases in profits between 1 and 20% each year and 3 between 21 and 40%.

Education in entrepreneurship can be converted into an aggregate of the business experts thinking; if entrepreneurship is an integral part of an educational system it should be reflected in each institution, within the organization of each classroom and the proper knowledge of the teachers along with high degrees of decentralization and empowerment, as the company is opposite to the command and control. Education in entrepreneurship adds, should create and strengthen sense of ownership and results, reinforce the sense of freedom and personal control for things to happen, maximize opportunities for individuals to take responsibility and fulfill tasks, reinforce the notion of responsibility and see through things, have an orientation toward excellence (Gibb, 2007).

Education initiatives in entrepreneurship should articulate this teaching with the why, where, how and whom. In addition, it should be clarified whether the training is finished with the creation of a company. There are already documents where you can find how to teach entrepreneurship, why teach it, what to teach and how, but in Latin America these proposals are yet to be found (Middleton & Donellon, 2014). In Colombia, the Ministry of Education plans to teach how to create businesses but it does not exist a specific plan with targets and indicators; to date, there have not been assessments of that project (Ministry of National Education, 2012). There is a gap between how educators help entrepreneurs to become entrepreneurs (Middleton & Donellon, 2014). The impact of previous education in the creation of enterprises appears to be low in this sample; 80% did not find favorable environment to create business in their university, although they do rely on knowledge acquired there (80%).

The average age when creating the company is 27 years. 17 entrepreneurs founded the company while they were studying and 8 after completing their studies. These entrepreneurs ventured with small capital, less than 10 million (56%), between 11 and 30 million (36%) and between 41 and 50 million (12%). Business administration program graduates have not introduced major innovations; developments in terms of new goods and services have not been revolutionary, what they offered was either the same or very similar to those of the competition (Berdugo & Gámez, 2014).

There are several stakeholders interested in entrepreneurship education, given its perceived benefits at both individual and societal level: policy makers, students, industry and academicians. Policy makers also believe that increased levels of entrepreneurship can be reached through education (EU, 2006), and especially entrepreneurship education. In Latin America, entrepreneurs work in the formal and informal sectors; for the ones in the formal sector, the desire of leaving unemployment and informality prevails, for the ones in the informal sector, limited access to financial resources and knowledge prevent them from entering the formal sector (Hernandez, 2008). Entrepreneurs in our context characterize themselves as sole proprietors, heads of households, with incomplete secondary education, in the tertiary sector, with less than two minimum wages for an income, without affiliation to social security, mostly with non-written employment contracts and working from home or without permanent premises. Business interruption, understood as people who in the past year have closed, liquidated or sold their companies, is equivalent to 5% of Colombian entrepreneurs. Business creation amounts to 900,000 companies.

To young entrepreneurs (24%), middle-aged entrepreneurs (27%) are added, and it is rare to find entrepreneurs with little schooling, on the contrary, 15% enter the business world with postgraduate studies (Varela, 2015).

Theoretical frameworkWorld Economic Forum defines competitiveness “as the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country. The level of productivity, in turn, sets the level of prosperity that can be reached by an economy (…) In other words, a more competitive economy is one that is likely to grow faster over time (2014, pp. 4)”.

“Entrepreneur” in English refers to the producer, the one who makes, manufactures, fabricates, process or creates a good or a service. In the United Kingdom is the one who directs an enterprise or is a businessman, and in the United States or Canada is the one who negotiates or finance businesses, directs them or organizes them. Another definition relates to the one who makes himself through independent activities, who trusts in himself, the self-sufficient, and the one who uses entrepreneurship. It includes the strength, the security, the quickness, the determination, the stability and the permanence, the prosperity, which gets close to the fair and tries it; it also mentions what is rare and scarce, and what is held dearer. In French it is the one of Enterprise (Gámez, 2013).

Ansari, Bell, Iyer, and Schlesinger (2014), propose how to instruct through an appropriate curriculum and an ecosystem that helps develop thinking and action of entrepreneurial leadership. Entrepreneurship goes beyond an act or a thought. From this theory, society becomes a way of building knowledge and learning and history as a fundamental aspect of education, in other words, you never start from scratch. For Rae (2014), it is possible to teach entrepreneurship. Its teaching must adjust to the specific economic situations and contexts. At the same time, the economic model demands from education adjustments so competences needed to starting businesses are taught. Since the implementation of technologies and recognizing the best practices used in managing learning, Lahm and Rader (2014), highlight the role of technology platforms, social networks and online communities as key learning strategies in teaching entrepreneurship. Moreover, technology is an ally of entrepreneurs allowing them to stay updated of trends in products and brands, and in a timely management of their contacts.

Ji and Zhao (2014), investigate about the constitutive elements of the educational practices for employment and entrepreneurship. This system of educational practices contains: (a) students, (b) teachers, (c) “career” and (d) environment. However, Hunter (2014) considers that the teaching of entrepreneurship must overcome the schematic application of models that ignore the social context in which they operate and will be applied. These models should be modified with the knowledge and the way of teaching of local authors to build more relevant school curriculums.

Iacob and Nedelea (2014) consider entrepreneurship as a key factor in China's economic change. This analysis is based on three levels: (1) individual, (2) corporative and (3) state.

Gamage and Wickramasighe (2014) study the links between society, community and entrepreneurial activity around South Asia, concluding that entrepreneurship is a social phenomenon and requires an examination by the socio-cultural values that affect it.

The educational projects in entrepreneurship according to Bliemel (2014) include the internal analysis that starts in the classroom. His approach uses a few strategies; one of them is “turning the classroom” and has to be completed with other two: one conventional and another that changes the logic of inside-outside, focusing on how to transform the know-how. Within this framework, entrepreneurship becomes an experiential and practical process. A proposal of this type requires structural changes in the educational system that redefines the teaching methods. Chen (2014) aims to analyze the flow of talent attraction and expulsion. It is based on the theory of talent attraction and the flow theory to talent. It suggests that technology, innovation and entrepreneurial status, on the one hand, together with the professional status and condition in educational development, on the other hand, are factors influencing advantage in attracting talent (p. 1277).

Robinson and Stubberud (2014), highlight the importance of teaching through the implementation of differential teaching-learning experiences that at the same time turn into innovations in the methods of education. Dobratz, Singh, and Abbey (2014), criticize the minimalist conception of internships based on requirements that only benefits the students and not institutions and employers. They emphasize the value of internship programs and their relation to the theory of entrepreneurship.

Saeed, Muffatto, and Yousafzai (2014), with 805 students from universities in Pakistan, show the positive impact of increasing university training in entrepreneurial activities. Entrepreneurship education should include all those strategies to increase self-efficacy engaging students in tasks that involve risk-taking and innovation.

Täks, Tynjälä, Toding, Kukemelk, and Venesaar (2014), in a qualitative research with engineering students describe four learning experiences in entrepreneurship: (a) the first step toward self-learning, (b) preparation for working life, (c) the way for a possible self-employment and (d) the context for developing leadership and responsibility of a successful team.

Claudia (2014) presents the revision of the extracurricular activities in entrepreneurship as collaborative in the development of immersion learning and entrepreneurial experience. She also proposes as a complementary way to formal education, learning by doing, meaning the application of experiential approach as an integral part of education.

Ortega, Cano, Salcido, Villarreal, and Villarreal (2014), analyzed the entrepreneurial ecosystem that improves the sustainability of projects over time, and the impact of education, on the one hand, in the training of entrepreneurs and on the other, the emergence of prominent people and knowledge creation.

Sánchez (2011), made several questions on education and entrepreneurship relationship: what is the meaning of education in entrepreneurship? Is entrepreneurship education the same as the training for creating SME's? What is the different from Business education? What is the difference between education for business and education in the company? Do these educational programs have an impact on entrepreneurial activity?

Finally, Osorio and Pereira (2011), propose the value of an entrepreneurship formal education (p. 15). From the social cognitive theory, the authors present a model of a triangular entrepreneurship education, where the education is located in the center and is affected by the environment, the entrepreneur and the enterprising action, which is based in training.

An entrepreneur is characterized by finding problems and solving them, it settles objectives, controls his destiny, searches prestige and recognition, though his main goal is not to obtain economic benefit. He is worried more about present and future, the planarization, the organization, the efficiency and the technology. According to Smelser (Quoted by McClelland, 1989) their values can be modified by the educational system, the religion, the family and society. The goals set by the entrepreneur are moderated and their achievement asks for feedback.

Latin America needs more entrepreneurs and new enterprises for promoting the economic and social development. For stimulating its apparition Education has been called for encouraging Entrepreneurship (Guzmán & Liñán, 2005), with rules and laws. Nonetheless, when Entrepreneurship is stimulated through the Law 1014, there is some positive evidence of creation – outline fact from the creation of the Emprender fund – but they keep the high evidence of the closure of enterprises.

In this document, entrepreneur is an individual who leaves a little bit of peace of mind by seizing opportunities and implementing them; its impact on society creates jobs and income, expresses the will to change society in a positive way, reveals high capacity for work and dedication, generosity, rigor, teamwork, hopefully with respect for the ways of thinking and acting of others, and if possible, are contributions to the construction of a stronger social fabric that contribute effectively to building a harmonious and dignified society (Gámez, 2013).

How it is taughtLatin America can reduce poverty and inequity with entrepreneurial activity expressed in business creation. Entrepreneurship in Colombia was started to be promoted from the State through the formation for work with the creation of SENA (1959); at the end of the XX century the first entrepreneurial development centers were created and at the beginning of the XXI century the promotional laws of MIPYMES and entrepreneurship were issued. The creation of enterprise has had quite a dynamic behavior according to the GEM but in specific conditions that include informality.1 The creators of enterprise must exceed the figures of the rest of the world.

The financing problems are concealed within a limiting factor in the creation, growing and development of enterprises; although the financing sector has grown and has a more complete portfolio, entrepreneurs and businessmen have difficulties for reaching resources because of the lack of guaranties, risk and credit history (GEM, 2006).

In Colombia, there are 134 universities distributed in 32 regions, the highest offer of universities is located in the city of Bogota with 30, followed by 17 in Antioquia and Valle del Cauca with 15. And specifically of the business administration programs, the country has 1427, Bogotá with the highest offers has 414, followed by Antioquia with 201 and Valle del Cauca with 136 (Snies, 2015).

Entrepreneurship entered the classrooms of higher education in the mid-twentieth century, with special emphasis on the role of the entrepreneur that creates business, first formulating a project and later the business plan. However, it has been addressed in several universities the figure of the social entrepreneur (see SEKN Social Enterprise Knowledge Network, the Social Enterprise Initiative IESO, Colombia and Ashoka “Buena Nota”, among others). Entrepreneurship is generally associated with contributions to economic growth, efficient use of resources and income generation. It is also related to the effect of imitation of successful entrepreneurs and also creates opportunities for others. The assumption of the risks associated with entrepreneurship is due to the impact of the family environment, social context, culture and, of course, education.

The entrepreneurship training can enhance the creative abilities of people, their values, to acquire planning skills, learn to act in the midst of uncertainty, set goals, ability to solve problems, implement creativity through innovation, information management and forecasting (Gámez, 2013).

Entrepreneurship is taught at undergraduate and graduate programs through lectures (93% of universities), with the own limitations of the theoretical approach. Can entrepreneurship be taught in the classroom or is just the repetition of knowledge? (Herrera & Ortiz, 2010). Besides lectures, entrepreneurship is taught trough conferences and discussion groups with an 88%, followed by research groups with a 45%. Although the lecture is the primary approach, universities use other training strategies like having companies doing presentations in the classrooms (80%), business exhibitions (71%) and managerial games and competitions with other universities (50%). Other tools include visits to companies (80%). Entrepreneurship is promoted through exhibitions (75%), discussion groups and contests (Herrera & Ortiz, 2010).

Entrepreneurship education can help students to succeed in an increasingly dynamic business world: the employees who have received an entrepreneurial education are able to think like entrepreneurs, facilitating corporate entrepreneurship to address global competition and technological changes (Singh & Magee, 2001). It is uncommon to use tools such as simulators, technology parks, trading games, business conferences, tutorials, participation in stock market games, the development of guidelines, corporate samples, accessing to entrepreneurship electives, forums, identification of entrepreneurial characteristics tests, awareness talks with students, workshops, trade missions, business panels and laboratories (Herrera & Ortiz, 2010). The processes of training and research in entrepreneurship are concentrated in Bogota, Cali, Medellin and Barranquilla.

Some of the new entrepreneurs (24%) consider that the idea of creating their own business emerged from previous jobs where they gained experience and knowledge; others acknowledge the support of some teachers (16%). The companies were created between 1999 and 2012, in the secondary sector (12%) and in the tertiary sector (88%). The companies are micro initiatives (64%) and small companies (36%) that generated 220 jobs. The impact of education in the creation of these companies appears to be low in this sample; 80% did not find a favorable environment to create business in the University, although they do rely on knowledge acquired there. The new entrepreneurs which are higher education graduates have not introduced major innovations to the market; developments in terms of new goods and services have not been revolutionary; what they offered was either the same or very similar to those of the competition (Berdugo & Gámez, 2014).

The tendency to assume the teaching of entrepreneurship in the academic programs of Business Administration is detected. The business plan is the center of the academic activity; therefore, the competences are defined from the instrumental and the achieving of results.

It is anticipated that the law 1014 of 2006 promotes entrepreneurship through education; however, this did not have a diagnosis of the entrepreneurial phenomenon. Its purpose is to promote entrepreneurship to create sole proprietorship companies. This law did not ensure the financial resources to achieve tangible results.

Teaching entrepreneurship is supported by entrepreneurship units that State through Entrepreneurship Fund (Fondo Emprender) has created with the institutions.

Robinson and Stubberud (2014), highlight the importance of teaching through the implementation of differential teaching-learning experiences that at the same time turn into innovations in the methods of education. It works with cases of successful entrepreneurs and tools such as business exhibitions, conferences of successful entrepreneurs, company visits, among others. Business ideas that are created in academic environments are not supported after.

GEM longitudinal analysis between 2006 and 2013 shows that there is an intention to create enterprise but not executed. By 2013, 77% of Colombians think that business creation is a way of life and gives status, however, the percentage of people with the ability to identify opportunities and needs for creating and managing a company falls to 65% – potential entrepreneurs, people who will create business in the next three years is lower (55%) – intentional entrepreneurs-and the percentage of those who have already made some effort and paid wages for a period of three months is only 14% (Varela, 2015).

Supporting entrepreneursIn developed countries incentives to supply and demand of enterprises and entrepreneurs are promoted; in developing countries the lack of resources is encouraged through education, through vocations and entrepreneurial skills, and with few resources: “The creation of companies based on knowledge is neither linear nor automatic and faces a number of constraints, both from the market and from the capabilities of entrepreneurs to achieve successful performance” (BID, 2004, pp. 248). Latin American entrepreneurs are young, with higher education and previous work experience, and are oriented to domestic markets. They are influenced by their families, the education system and previous jobs. They participate in networking for project formulation, strategy and development of the idea, currently have the intentions of business creation but are not executed, due to perceived risks and difficulties. The institutional offer ranges from support for specific populations to comprehensive coverage, advice and training and few include funding (Gámez & Navarrete, 2009).

The main difficulty young entrepreneurs perceive are their finances, followed by the economic climate, the procedures and the fear of failure. Fear of failure prevails when the father is a businessman. 97.7% are young respondents that perceive more than one risk for start-ups; the first risk is the uncertainty in income; followed by the fear of ruin 22.1% and personal failure, 13%.

In Latin America entrepreneurs work with the formal or informal sector; in the first case the desire of not staying unemployed and informality prevails, in the second, access to financial resources and knowledge prevent them from entering the formal sector. Out of necessity entrepreneurs can be described as sole entrepreneurs, heads of households, with incomplete secondary level, in the tertiary sector, with income less than two minimum wages, without affiliation to social security, mostly with non-written employment contracts signed and work from their homes or anywhere (Hernández, 2008).

In Colombia there are alternatives aimed at young people with a chance of financing, along with advice and training, some important ones are:

Fondo Emprender (Entrepreneurship Fund): it was created to finance business projects, having as beneficiaries SENA trainees, students who are about to finish their undergraduate or postgraduate programs and with no more than two years after completing their studies, the entrepreneur has a seed capital that depends on the jobs generated by the project (Fondo Emprender, 2009).

Although it is a good option, companies are not sustainable over time, according to Fonade, there are identified problems in the formulation of business plans, sales projections too optimistic on a poorly estimated demand, a lack of self-measuring and the time of implementation and its impact on sales targets is not included (2010). According to Gamez, problems in defining the business project, market aspects, deficiencies in the research, erroneous estimation of demand, poorly structured market strategies, undervalued budgets, projections without methodological or technical support, insufficient financial assessment, no benchmarks against industry, no risk analysis and mitigation, have been detected.

The results of the seed capital that the fund provides to undertake projects of higher education graduates – show that the problems of the projects supported include: deficiencies in studies to estimate demand problems, poorly structured market strategies, mixture of budgets from undervalued market, do not have clear goals and specific objectives and the estimates are quite optimistic projections that are not supported technically with proven methodologies (Gamez, 2008a,b). No evaluations have been performed to the new graduates of the Fund. Between 2003 and 2015, with public funds, 3,494,185 companies in 607 municipalities have been created per year, with 316.977 million of Colombian pesos (102 million dollars) to generate 39,817 jobs (Entrepreneurship Fund, 2015).

Finbatec: supports the creation of technology-based and innovative businesses; sponsored by Colciencias and the BID. It intends to form a bank of technology-based and innovative business projects and encourage venture capital investment. The program supports technical structuring of investment projects, legal consulting and management and business conferences to investors. In recent years the project lacks funding which has stopped working.

These supportive initiatives complement the education system to consolidate entrepreneurship in the school classrooms. Therefore, if there are gaps in the training programs – definition of the problem, poor market research, errors in estimates of demand, poor market strategy, errors in estimates, projections without methodological or technical support, poor financial assessments, few risk analysis and mitigation, among many-, resources and financial support may be wasted.

According to the Bogotá Chamber of Commerce in 2013, in the area of Bogota and Cundinamarca 18,423 companies were discontinued, it is worth noting that 17,601 (95%) of these were small businesses. According to economic activity the wholesale and retail trade repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles has been the hardest hit with 6878 (37%).

MethodsThis is a descriptive document with a qualitative analysis of the result of the research made by Herrera and Ortiz (2010) and Berdugo and Gámez (2014). Answers the question about the evolution and development of entrepreneurship education in the Business Administration programs in the city of Bogotá. Secondary sources were consulted, a sample of 43 universities with administration programs, one university and its graduates between 2008 and 2013, and the sample of GEM with more than 2000 interviews in Colombia.

AnalysisEntrepreneurship seems to be assumed in the institutions as a synonym of people having the ability to create business in order to generate wealth, to achieve economic growth and as a solution to the unemployment of its graduates; the “intrapreneurship” is seen as the birth of creative employees. The business plan is the center of the academic activity; therefore, the competences are defined from the instrumental and the achieving of results, which some call “practical”.

Activities of creativity and innovation aimed to discover business ideas and opportunities are included. It works with cases of successful entrepreneurs and tools like business exhibitions, conferences of successful entrepreneurs, company visits are used, among others. Business ideas that are created in academic environments are not supported after (Pérez, 2014).

In 2013, the number of Colombian enterprises created out of necessity increased (20%) and the percentage of enterprises created out of opportunities decreased (39%). The 65% of Colombians are potential entrepreneurs, 55% are intentional entrepreneurs, 14% are emerging entrepreneurs and 6% reached 42 months with the company (Varela, Moreno, & Bedoya, 2015).

Although 33% of the Bogotá universities include entrepreneurship in the description of the professional profile of its graduates, it is not reflected in business creation and sustainability. Training activities are done in undergraduate programs through traditional lecture, exhibitions (75%), lectures and contests (Herrera & Ortiz, 2010).

Entrepreneurs attribute to their family environment the tendency to business creation (48%); consider that emerged from previous jobs where they acquired experience and knowledge (24%), the support from some of their teachers (16%). Companies created by graduates of a Business Administration program between 1999 and 2012 are located in the secondary sector (12%) and in the tertiary sector (88%). The companies are micro initiatives (64%) and small companies (36%) that generated 220 jobs.

Only 11 companies have had increases in profits between 1 and 20% each year and 3 between 21 and 40%. Only 80% did not find a favorable environment to create business in the University, although they do rely on knowledge acquired there (80%). The new entrepreneurs have not introduced major innovations to the market (Berdugo & Gámez, 2014).

The guidelines of the law 1014 of 2006 for promoting entrepreneurship through education are followed. The 1014 of 2006 Law – Entrepreneurship Law – did not have a diagnosis of entrepreneurial phenomenon; its purpose is to promote entrepreneurship through a cross-sectional lecture in all educational institutions to promote the business creation. Entrepreneurship law did not ensure the financial resources to achieve tangible results.

Teaching entrepreneurship is supported by entrepreneurship units that State through Entrepreneurship Fund (Fondo Emprender) has created with the institutions.

Toward a proposal to teach entrepreneurshipSmall gains in most pillars of the GCI contribute to creating a more conducive ecosystem for entrepreneurship and innovation: higher education and training (65th, up five); business sophistication (43rd, up two); and the technological readiness pillar, which constitutes China's weakest showing in the GCI, (83rd, up two). Colombia is evidenced by a lack of coordination and duplication of functions between public entities; lack of information; little interaction of this entities with companies and universities; and the lack of leadership to prioritize and direct the implementation of the strategy for science, technology and innovation as the engine of development for the country in the long run (Gómez & Mitchell, 2012). According to Fonade (Gamez, 2008a,b), out of 100 new entrepreneurships, 62% survive, from the remaining 38%, 14% stays in the launching stage, because of problems with partners, short time dedicated to the business, among others. On the other side, 25% of the companies have not met their indicators of sales, being unsustainable over time; they have not exceeded US 115,000 in the first year and its start-up stage lasts for about 4 or 5 months. Business projects present failures since the beginning of the identification of the problem; they cannot identify the need that they need to meet and the opportunity that they can achieve.

The deficiencies of the market are evident, the studies present failures, which generate a wrong estimate of the demand, the strategies of the market are not correctly structured from the very budget, as they are not included in the global budget, the goals are imprecise and optimistic, which make projections lack a proved technical methodology. From a financial perspective there is not evaluation, they grow short in the risks analysis and strategies of mitigation, there are no parameters of comparison with the competitors, and they do not define discount rates. Because of that, lots of business projects disappear in the short term or they do not manage to become sustainable, dynamic, competitive, innovative companies with an added value.

The abilities of an entrepreneur can be harnessed through education; in the academy it is possible to be identified if an entrepreneur inclines by the company creation. In that case three stages are distinguished: The one of the potential industrialist, the one of the rising industrialist and the one of the dynamic industrialist. In each case the education can sensitize, support and contribute in the profit of the enterprise quality (Guzmán & Liñán, 2005). The person who uses entrepreneurship is a user of predictions, in most cases it is brought closer the art, and requires intuition and common sense.

These future explorations are based in three methodologies: (a) Consulting with experts that collect structured knowledge; (b) Trends and extrapolations, which include models for identifying regularities of the past; and (c) Tools of thinking for individual use (Fontela, Guzmán, Pérez, & Santos, 2006). Creativity is understood as a process and capacity, with uncertain results that arise from experience, intuition and expectations. What an entrepreneur expects of his work is very much alike to the tension an artist feels when creating works.

Kantis et al. (2002) identified three stages of the enterprise entrepreneurship. The gestation of the project, the running of the company and the initial development of the project; the gestation stage includes the motivation and the competences of the entrepreneur, the identification of the opportunity and the elaboration of the project.

The running contemplates the decision of starting the enterprise activity and the access to the resources to begin. Finally, the initial development of the project includes the introduction of goods and services to the market, and the management of the first years.

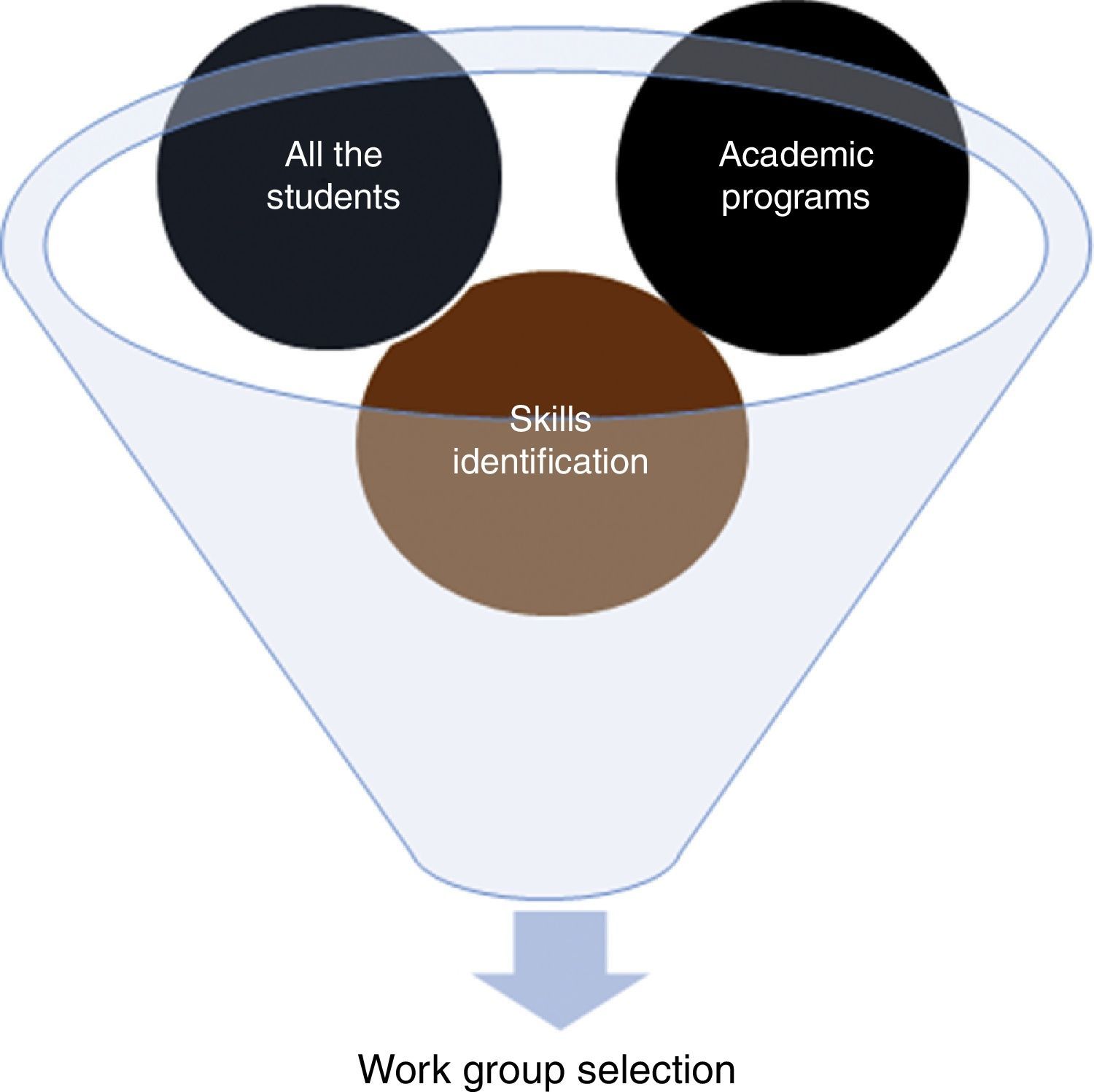

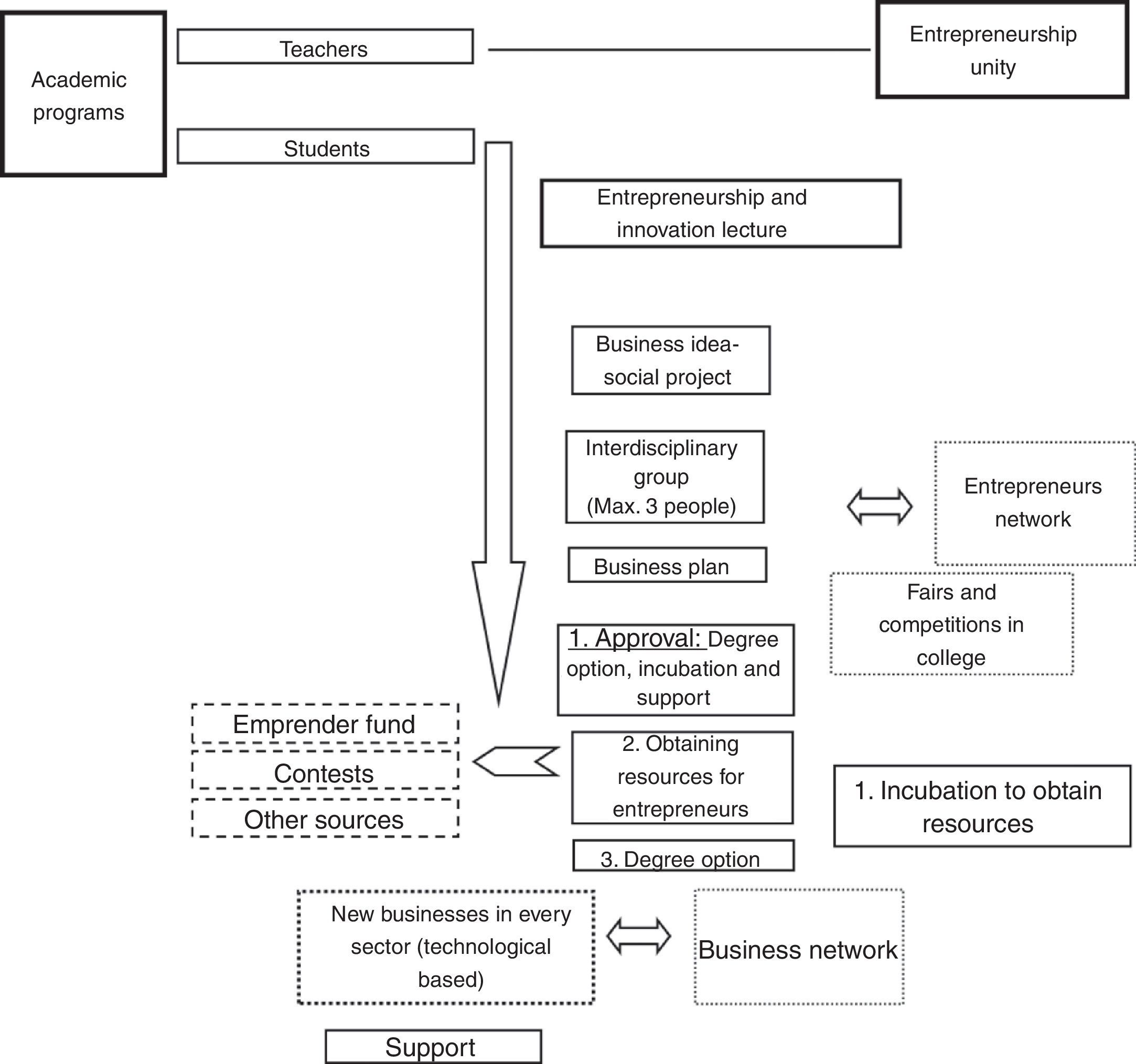

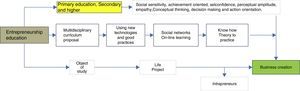

According to the prior context described, where entrepreneurship education is a task for the Business Administration programs, with emphasis on undergraduate programs, that support this training in classroom lectures, some visits to companies, exhibitions, discussions and contests (Herrera & Ortiz, 2010), and all students are taught equally, without considering their family environment, their inclination to create company, their previous work, their experiences and knowledge, where some teachers transcend their support to the entrepreneur beyond the classroom, companies are created in the secondary and tertiary sectors (Berdugo & Gámez, 2014). We present the following proposal for tertiary education in entrepreneurship with relevancy, timely and focused on innovative ideas, originated in a multidisciplinary point of view, for undergraduate and graduate programs allowing the structuring of ideas most likely to access resources that become sustainable enterprises with greater impact on the Colombian economy (see Fig. 1).

The proposal is based on the possibility that entrepreneurship can be taught, with a multidisciplinary curriculum – interdisciplinary working groups – that suits the conditions of Colombian society – ecosystem, the application of technologies and good management practices for learning (Ansari et al., 2014; Lahm & Rader, 2014; Rae, 2014), the use of social networks and online learning communities as support strategies for teaching. The proposal is supported by students, teachers, the choice of entrepreneurship as a “career” and the environment (Ji & Zhao, 2014; Hunter, 2014). This proposal also includes the individual, corporations and the state, and its links with society, community and entrepreneurial activity (Gamage & Wickramasighe, 2014).

This entrepreneurial ecosystem can improve the chances of sustainability of projects over time, and impact the education, on the one hand in the training of entrepreneurs and on the other hand, the emergence of eminent persons and the creation of knowledge (Ortega et al., 2014).

The teaching of entrepreneurship includes internal analysis that starts in the classroom that is “turned”, so from there conventional teaching function is fulfilled and becomes know-how, that is, the passage of theory to practice (Bliemel, 2014).

And here is where resides the importance of teaching through the implementation of differential teaching-learning experiences that at the same time turn into innovations in the methods of education (Robinson & Stubberud, 2014). Entrepreneurship education should include all those strategies to increase self-efficacy engaging students in tasks that involve risk-taking and innovation (Täks et al., 2014), with activities outside the classroom as a collaborative part in the development of immersion learning and entrepreneurial experience, facilitating the “learning by doing” (Claudia, 2014). According to Gómez & Mitchell (2012), entrepreneurial teaching must have a strategy for science, technology and innovation based on human capital, knowledge generation, dynamic entrepreneurship and productive innovation in the long term, and has to be supported by strong institutions and articulated to a competitive environment conducive to business development. On the other hand, Varela (2015) argues that in the future, universities and higher education institutions should provide good and adequate preparation for the creation of new enterprises and growth for the ones already established; training in administrative, management and business management will be very important.

Object of study: Entrepreneurship is a way of thinking and acting, it is a behavior that helps to develop free and happy individuals. Entrepreneurs are people who seize opportunities or face problems responsibly; they are also agents of social change with impact on other individuals and communities. Not all individuals are entrepreneurs and creators of companies or projects, but all of them will discover and enhance their skills of creativity and innovation. The entrepreneur who creates company is a key driver for the economy because it impacts with technological changes, the generation of wealth and job creation. Entrepreneurship is a life project.

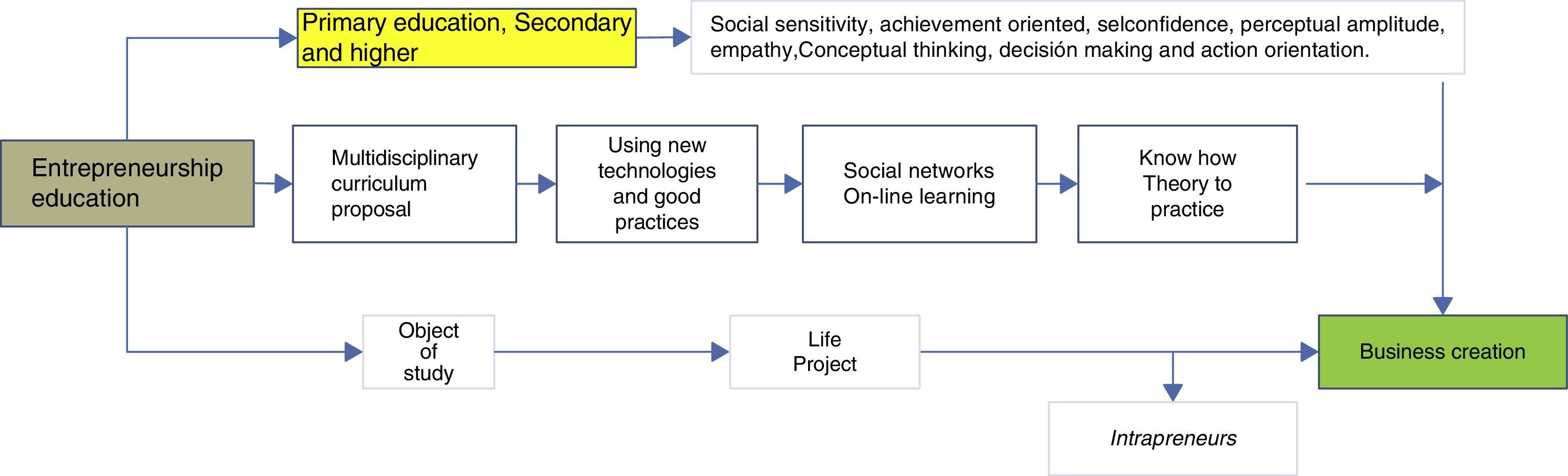

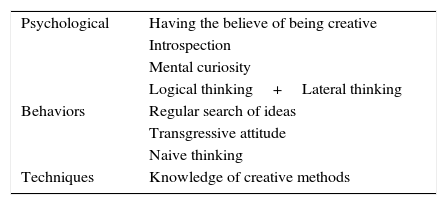

Entrepreneurship can be taught, and an entrepreneurial spirit can develop in an educational process. Entrepreneurship education is a learning process that lasts a lifetime, starting in elementary school and cuts across all levels of education (Gámez, 2013). It can be formed into skills and attitudes that enable a person to recognize and exploit opportunities – creative person – (see Table 1). Entrepreneurship education should promote critical and proactive thinking to find new options for personal and professional development that impacts their social environment (Gámez, 2013; Pérez, 2014).

Skills of a creative person.

| Psychological | Having the believe of being creative |

| Introspection | |

| Mental curiosity | |

| Logical thinking+Lateral thinking | |

| Behaviors | Regular search of ideas |

| Transgressive attitude | |

| Naive thinking | |

| Techniques | Knowledge of creative methods |

Creativity is essential in entrepreneurial activity, understood as a mental activity (Gámir et al., 2007) process and capacity, with uncertain results that arise from experience, intuition and expectations (see Table 1). Being creative is to see things that others do not see and suggests two phases: Divergent creativity that opens the spirit to play and combining, and Convergent creativity that selects the strengths and weaknesses of each idea (Ponti & Ferràs, 2008).

A teaching model of entrepreneurship that addresses the specificities of Latin America is proposed. The model should be aimed at those interested in business creation and have the skills and attitudes needed: not all will create a company. The lecture for those who do not start a company can be useful to generate ideas, enhance creativity and participate in other projects – intrapreneurship –. What subjects are taught in entrepreneurial education? They should include the impact of climate change in the tropics, strength of materials, bio-prospecting, biotechnology, geology, energy, electronics, logistics and design; and areas of public interest such as health, quality of education, building citizenship and social inclusion (Gómez & Mitchell, 2012, p. 29). Is it just a proposal to supplement the shortcomings of the neoliberal model?

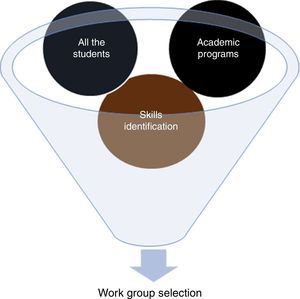

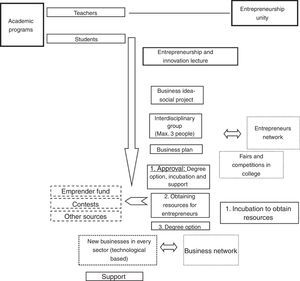

Entrepreneurship in all levels of education: In primary education entrepreneurship education can increase creativity, help understanding risks and planning; in middle school taking consciousness of entrepreneurs who manage to create and sustain a company starting with small things is favored; in college you can learn to work with others and form – interdisciplinary – and discover the different types of entrepreneurs: business person, intrapreneur, public, social, among others. Creating business in Colombia can be a competitive option to the precarious and insecure jobs, and that the retirement income is insufficient to live with dignity (see Fig. 2).

The student must be educated in managing uncertainty and doubts, meaning that, all human beings are fallible, therefore, the entrepreneur must learn to analyze, question and propose new ideas. It is also trained to identify opportunities in economic, technological, cultural, social and environmental contexts, among many, and learn to look at them together. For the case of entrepreneurship of a company, competences of individuals must be defined: social sensitivity, achievement orientation, self-confidence, perceptual amplitude, empathy, conceptual thinking, decision making and action orientation.

Students should be taught to work together to improve social cohesion and promote collaboration networks to meet the new economic and social settings (Pérez, 2014).2

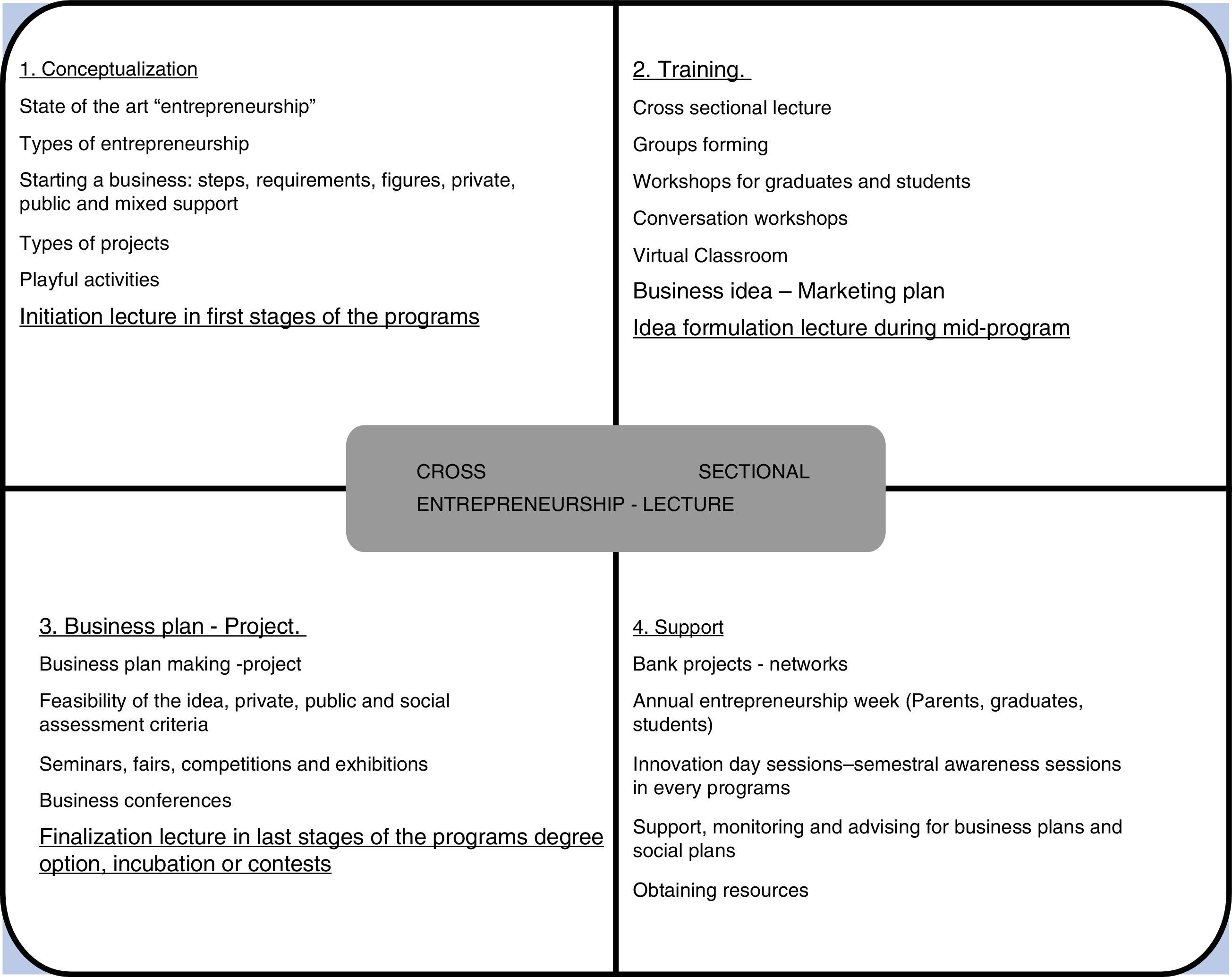

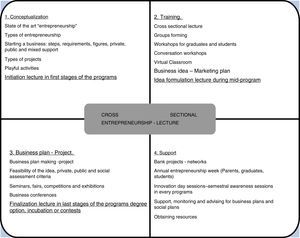

It will have four stages: theory of entrepreneurship in the early stages of the academic programs, formulating ideas in the middle of programs, formulation of business – social plan – social end and post project support.

Student: It is characterized by a high capacity to work, the need for achievement, organizational skills and adaptation to contexts, confidence and desire for independence. While not all individuals can be entrepreneurs, they can learn some of those skills. Education enables entrepreneurial skills to be learned and, therefore, from the education system encourage entrepreneurship. This student wonders about educational approaches, some focused on training and specific steps for creating business processes, others pursuing the development of entrepreneurial personality. Can education in entrepreneurship become a set of thoughts of business experts? Is it formed in developing business plans or in the discovery of entrepreneurial spirit?

In this project proposal the student is a part of the process as a subject in its context; therefore, it promotes autonomy, establishment of relations between the needs and problems, and the approach to addressing the training to the diversity of participating students. Every human being is unique and unrepeatable and learns in different ways and with dissimilar rates of learning, therefore, the teaching of entrepreneurship is based on the skills of the subject and considers the student as a rebuilder of their own knowledge. Entrepreneurial training is pursued through promoting academic entrepreneurship for all academic programs, and can be mixed with virtual lectures, workshops, simulations, company visits, entrepreneur's visits to the class and follow up activities. This training is complemented by the organization of competitions and prizes for all types of entrepreneurs (Gámez, 2013; Herrera & Ortiz, 2010; Pérez, 2014; Varela, 2015).3 A first step is the design of the lecture with the following characteristics:

- 1.

All students taking the course will be evaluated to determine their risk-taking skills, motivation, creativity and personality.

- 2.

It is for students of all academic programs to promote interdisciplinary training.

- 3.

The ideas will be presented by groups of three people from different academic programs.

- 4.

It has to include people training for intrapreneurship. They will not be business creators but they are people capable of solving problems within the organization.

- 5.

Training in generating ideas

- 6.

Creativity

- 7.

Innovation

- 8.

The samples of business projects have to include visits of successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs.

- 9.

A business plan has to be implemented as a degree requirement or as a degree option; it does not require funding but to have rigor in its preparation.

- 10.

Entrepreneurs and teachers have to follow up all of the students processes.

Drucker (1985), consider the entrepreneurial mystique, it is not magic, it is not mysterious and it has nothing to do with the genes. It is a discipline. And, like any discipline, it can be learned. Shapiro and Varian (1999) claim that entrepreneurs are not ‘born’, rather they ‘become’ through the experiences of their lives.

For this reason the entrepreneurship education should not be confused with economic or business education, where specific knowledge of economics and management is disseminated, the entrepreneurship involves the promotion of certain personal abilities that provide the basis for enterprising activity and fostering self-employment as the choice of life/career (Vidic, 2013).

The entrepreneurship and innovation lecture has among its objectives for the participating students to:

- •

Experience developing a social Project or a business activity in a organized way with proper academic support

- •

Regardless of the academic program learn to identify business opportunities.

- •

Can design strategies: design, production, purchasing, financing, marketing, organization and implementation, aimed at consolidating a successful organization.

- •

Can foresee, establish and evaluate managing and control mechanisms

- •

Have the opportunity to live organizational processes with measured and calculated risk.

- •

Put into practice their skills of negotiation and conflict management.

- •

Strengthen their capacity for teamwork.

- •

Learn to give and receive feedback (positive and negative) about their performance.

- •

Achieve sharing social and business activities to general and specialized public.

Entrepreneurship is a learning process that occurs throughout the life of a person; it starts at home, still in basic education and training transcends during primary education, secondary and technological university, even after it, for continuing education (Pérez, 2014). Tertiary education can empower human ability to control, facilitating entrepreneurs move from ideas to facts, identify opportunities in the problems (see Fig. 3). The entrepreneur as creator and manager of a company looks for the forms of assuring his permanence in the time through the use methods, practices and styles of decision making.

Teacher: It is the key player in the teaching of entrepreneurship. Their roles begin in the review of curriculums and micro curriculums – syllabus – and involve in them the option of entrepreneurship and business creation. The teacher must review and update teaching methods and leave to the student the possibility of error, how to correct it, create risk mitigation strategies and permanently identify the opportunities and the ability to propose creative solutions. Identifying opportunities and problem solving must be lived in the classroom where the teacher as the highest authority, can be a participant who shares their mistakes with students.

The teacher should encourage the student's recognition of the role played by SME's as an employment option, but must find room for big companies and its corporate history. A complementary subject is the business history enabling the life and achievements of entrepreneurs and business people to be known, so students can use this information as a guide for their life plan.

From all professions – academic programs – business can be created, and the sum of efforts allows a broader point of view that can be applied into the economic and social world. Every teacher should approach the business sector to know from his perspective the business world and explain it to his entrepreneur's students.

It is intended therefore, that teachers understand and participate in the processes of creation, generation, formulation, implementation and evaluation of entrepreneurial projects to express themselves into viable, practical and sustainable solutions to real world problems.

- •

Know the tools, values and principles inherent to this knowledge.

- •

Design structures and processes to facilitate contact between people in order to encourage the creation and exchange of knowledge.

- •

Know innovation processes that support the construction of competitive advantages that will be translated into applied innovation in social and business projects, expressed in the R+D+I.

- •

Generate processes of innovation in the social field and in business with the frenetic changes that require continuous reinvention. Innovation is expressed in the introduction of new or significantly improved goods or services, processes, new marketing methods and new organizational methods in the internal practices of organizations.

- •

Select, use, generate and use relevant knowledge in the formulation of social and business projects.

- •

Acquire skills of creativity expressed in originality, spontaneity, inspiration, intuition, sensitivity, innovation and productivity

- •

Become entrepreneurs with the ability to find problems and solve them; therefore graduates are entrepreneurs who set goals and control their destiny, more concerned about the present and the future, capable of planning in search of efficiency, supported by technology.

- •

Entrepreneurs that are dreamers who build the future with imagination from the effective use of knowledge reflected in forecasts. Therefore, are efficient users of planning and technology, with passion, strong motivation and results-oriented, able to take responsibility, to transform their environment

Finally, the teacher must study and understand the benefits and risks that business creating can account for their students.

Research and extension: The entrepreneur who in real life is able to advance in his processes do not see its flaws as failures, on the contrary, he sees them as learning processes, skills that allow them to detect and generate new opportunities.

Entrepreneurship training should enable to start with small projects and work tirelessly to bring funding to enable acceleration, growth and sustainability. Higher education should promote and support all ideas of entrepreneurs to achieve its execution, as a form of applied research to show further tangible results to the publications of their academics.

Entrepreneurship education has to overcome the uncritical adoption of methods, concepts, theories and tools of external environments. Entrepreneurship education graduates act independently and creatively, identify opportunities to apply their knowledge, solve problems and take risks. The proposed curriculum in entrepreneurship must contemplate the social and economic development of Colombia. Myths about the business process and entrepreneurial skills should be included in their micro curriculums, identifying multiple, varied and unusual business ideas and turn them into business opportunities.

Analysis ability is expressed in developing business creation plans or business plans, which will include strategies to achieve business goals. Environmental analysis identifies key players who support the business process. Students from various programs must learn to work together to manage the achievement of resources of all kinds that the new company requires, directing and executing starting processes, growth and sustainability of the company.

Higher education can obtain resources with its entrepreneurs through incubation and acceleration. The work of incubators may include support for the most promising ideas long enough to achieve its sustainability with a proportional charge to their contribution.

Entrepreneurship will be included in the master's in business creation and management to complement the undergraduate degree education (Varela, 2015).

Teaching and research: The degree option must be associated with entrepreneurship understood from building a business plan and its continuity throughout the program to be complemented by all academic areas.

Academic courses that teach entrepreneurship is theoretical (1/3) and practical (2/3). Today we are educated to work and should be broader to include business education or social projects. Educate to create business involves developing leaders capable of detecting needs, propose ideas and create organizations with or without profit, in any sector of the economy, under any legal or administrative structure, for any purpose and any size.

Who teaches entrepreneurship must be a skilled academic but with ability for dialog with companies. His teaching contemplates the case method, internships, mentoring and coaching. The university evaluates and advises projects of the members of its academic community.

Regarding the process of education the university evaluates through interaction with students, observation, their reactions, proactive spirit and the desire for continuous improvement. Support for ideas to begin, incubate, accelerate and consolidate (see Fig. 4).

Should promote student participation in national and international competitions to promote their ideas, broaden the professional outlook and create partnerships for their business projects. Besides venture entrepreneurship expressed in the implementation of innovation through prototypes, patents and intellectual production pursued.

It has to be in full gear the entrepreneurship unit with its own budget and dialog with the governing bodies. One of its functions is to disclose the sources of funding – national and international – for projects for entrepreneurs, support and convocations – especially Emprender Fund – (www.fondoemprender.com/SitePages/Home.aspx).

Interdisciplinary between faculties promotes entrepreneurship of its graduates, complemented with training activities for trainers and mentors in entrepreneurship and business consulting (see Fig. 4).

Traditional methods of conducting business still persist in a knowledge-based economy. New business instruments and thinking are however also required. When knowledge based products and services become the source of organizations’ competitiveness, a variety of technologies are available to support the development and distribution of these products and services. The value of these knowledge-based commodities rests on their symbolic representation of information and not on their manufacturing value (Shapiro & Varian, 1999).

Evaluation: The result of the use of creativity is innovation and his loss affects the weakness of the company. Innovation, according to Schumpeter (1978), is reflected in new combinations of productive factors that are palpable in a new good or quality of good, a new method of production, the opening of a new market, the conquest of a new source of raw material, and the launch of new types of organization-There are strictly innovative companies, innovative companies in a broad sense, potentially innovative companies and non-innovative companies (Turriago, 2002). Society supports innovation through technology centers, technology parks, business and innovation centers, universities and transfer offices; in Europe's leading innovation countries are Switzerland, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany (Gámir et al., 2007).

Assess the entrepreneurial training is complex because it mixes objective and subjective criteria. Lautenschläger (2011) criticizes training in entrepreneurship because it recognizes that not all students have the same skills and to assess the impact difference is complex.

The proposed model must be evaluated every year in order to provide feedback to the academic community.

DiscussionGenerally, from these approaches it is possible to assume that the entrepreneur is the one that assumes the creation of companies, takes advantage of a gap in the market, uses the results of a research, uses R+D as competitive advantage and has action capacity. Nonetheless, a businessman can, at some point of his life, be an entrepreneur but businessman is not the same as being an entrepreneur, regarding innovation; an entrepreneur can be any person during a period of time and then abandon it, for this reason, if he stops being innovating, he will stop being an entrepreneur. An Entrepreneur is the one that in a place and specific conditions, deed and starts up new companies that renew the company's network of a society. From the university point of view, the focus is on demonstrating that entrepreneurship can be learned and taught; and that entrepreneurship has academic legitimacy as a scientific discipline. It is acknowledged in the literature that entrepreneurship knowledge and skills can be taught and developed when the appropriate environment is provided (Gibb, 2005).

The education can contribute to creating a more conducive ecosystem for entrepreneurship and innovation: higher education, training and business sophistication (World Economic Forum, 2014).

This analysis was based on programs in business administration from universities in Bogotá, which can be replicated in other areas of knowledge. It remains to be tested the lecture model in entrepreneurship to identify factors that favor the consolidation of Colombian companies, growth and sustainability.

Processes of entrepreneurship education evaluation are about to be addressed in Colombia. The weaknesses of the universities and how they have corrected them has not been identified. Nor is it clears what is the impact of teaching entrepreneurship and its relation to the formation and renewal of the business networks (Rico, Soriano, & Rubiela, 2012). Entrepreneurship and education are areas to explore to determine its causality, is there any?

For this document business creation was analyzed, however, social entrepreneurship can be studied in a country that is in the process of building peace scenarios and requires entrepreneurs to promote and live to the values and propose new forms of social innovation. It is expected that in the long term education contributes to form a strategy for science, technology and innovation based on human capital, knowledge generation, dynamic entrepreneurship and productive innovation, and supported by strong institutions and articulated, and competitive environment conducive to business development (Gómez & Mitchell, 2012).

ConclusionsUniversities show interest in educating entrepreneurs as viewed in its institutional documents, curricula, teaching methods and micro curriculums. However, the results show that education is theoretical, without sufficient regard to the practice, with little room to identify problems, take risks and make creative proposals, entrepreneurs are only sporadically seen in conferences and for short periods of time and results of the evaluation of the impact of education in shaping the Colombian business community are unknown. The correct teaching methodology and the right learning process will certainly be crucial to the success of the entrepreneurship education program. The growing interest in entrepreneurship education and the research regarding the impact of such education present some important policy question both for the institutions that deliver entrepreneurship education programs and for support organizations that provide funding (Raposo, Ferreira & Paço, 2011).

Strategies for short, medium and long term, should address the curricular adjustments and medium-term training plans according to sect oral needs, which is where training in entrepreneurship should be improved. Since the choice of having one job to achieve retirement is no longer viable, university should teach how to accept uncertainty to other age groups, with additional new teaching practices to create the business plan, with active role of the academic community: teachers, students, institutions, enterprises and state.

The current teaching of entrepreneurship does not focus on ways to reduce poverty and inequality, the intention of business creation is high but with low levels of execution and sustainability over time.

Entrepreneurship can be taught and an entrepreneurial spirit can be discovered and developed in an educational process that considers the characteristics of entrepreneur students, through a selection process. The proposed model allows developing skills and attitudes that enable a person to recognize and exploit opportunities, which addresses the specificities of Colombians.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Latin American countries are in a vicious circle: many laws and regulations are generated to control the uncertainty, the strange and the un-foreseeable. The more regulations, the economy will be more attached to major infractions; with the greater amount of laws there is more possibility of later conscious or unconscious transgression. The informality increases the probabilities of existence of informal entrepreneurship as well with his own ways of provision of public goods and forms of government (Hernández, p. 60).

America have few universities in the top 500: Argentina (6), Brazil (6) and Colombia (3), while other countries do manage to rank in the top 500 in the QS Ranking, Malaysia (5) and South Korea (12) (Private Council on Competitiveness, 2014, pp. 29).

Of course, each institution will develop the model and training strategies according to their circumstances.