As a result of the financial crisis, ethical banking has become a visible phenomenon that has aroused the interest of those clients that are disappointed with conventional banking, as well as that of the scientific community. However, research on ethical banking has just started, with several subjects pending consensus, such as the proper definition or identification of banks considered to be ethical. In view of the above, the objective of this study is, first and foremost, to define the common characteristics of all banks affiliated to the movement; empirically, we shall quantify the level of commitment with the same and, thus, as a result of this quantification, obtain a ranking that classifies the selected banks according to the scores obtained. Regarding the methodology used, the quantification of the level of commitment with ethical banking is done through a new index called SEBI (Social and Ethical Banking Index), designed from the characteristics defined in the study and applied to the banks identified as ethical due to being a part of the main network of this type of banking: The Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV).

A raíz de la crisis financiera, la banca ética se ha convertido en un fenómeno visible que ha suscitado el interés tanto de clientes decepcionados de la banca convencional como de la comunidad científica. No obstante, la investigación en banca ética se encuentra aún en sus inicios, con muchos temas pendientes de consenso, como la propia definición o la identificación de los bancos considerados éticos. Teniendo en cuenta lo anterior, el propósito de este estudio es, en primer lugar, delimitar las características comunes a todos los bancos adscritos a este movimiento para, en la parte empírica, cuantificar el nivel de compromiso con el mismo y, de esta forma, como resultado de esa cuantificación, obtener un ranking que clasifique los bancos seleccionados según la puntuación obtenida. En cuanto a la metodología empleada, la cuantificación del nivel de compromiso con la banca ética se realiza a través de un nuevo índice denominado SEBI (Social and Ethical Banking Index), diseñado a partir de las características delimitadas en el estudio, y aplicado a los bancos identificados como éticos por su pertenencia a la principal red de este tipo de banca: The Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV).

The international financial crisis has caused a dramatic growth of the so-called ethical banking, as it has been proven that the financial industry is often exposed to risks derived from amoral behaviours of a degree that frequently surpasses that of other sectors (Ferreira, Jalali, & Ferreira, 2016). As a result, a growing interest in this topic by banking clients and by the scientific community can be observed.

On the side of the clients, they have been massively resorting to ethical banking, avoiding a non-speculative way of banking, and looking for one that is more responsible, ethical and oriented towards the community than traditional banking. This fact allowed ethical banking to double its assets between 2007 and 2010, and grow more than 20% in the same period (Benedikter, 2011). This tendency makes us expect, in the coming years, an annual growth of ethical banking in Europe of approximately 13–15%, and brings along reasonable expectations of serving one thousand million people worldwide by 2020 (Benedikter, 2012).

Similar conclusions have been obtained from the reports of the GABV “Strong, Straightforward and Sustainable Banking” and “Real Economy – Real Returns. The Power of Sustainability-focused Banking”. These reports show, with data, the viability of this banking method, highlighting its profitability and solvency compared to those of conventional banking (GABV, 2012 and GABV, 2015). In this line, we would like to add that other researches coincide in that ethical banks have shown a more stable behaviour during the 2007 global financial crisis (Karl, 2015).

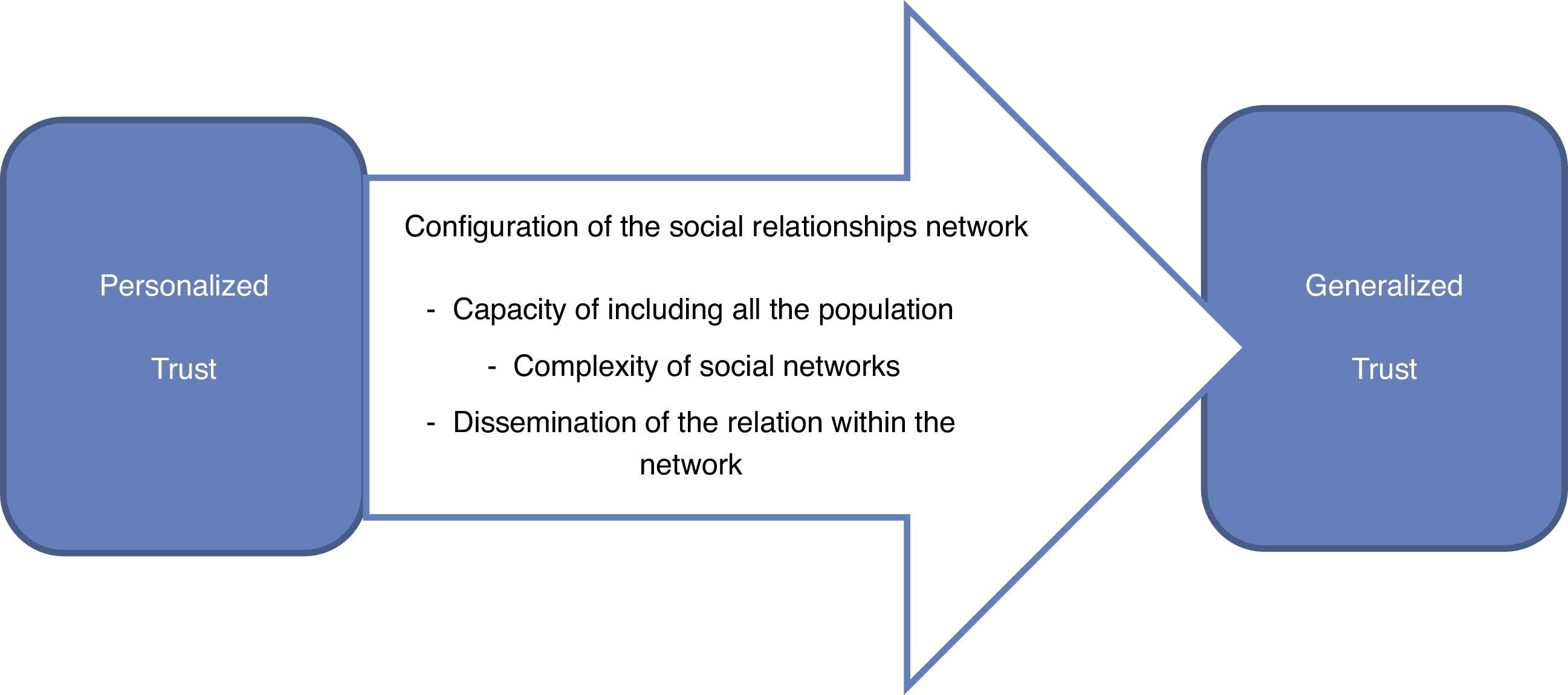

Also regarding the clients, we must stress the importance of social networks as a determining factor in the development of ethical banking, due to the fact that according to the network theory, the structure of social relations affects the context of the relations that can arise from the same, and thus it is virtually applicable to any aspect of social reality, including that of banking (Requena, 2003).

Concretely, social networks make it possible to include a greater portion of the population in trusting relationships and to simplify the relations between individuals and groups (Fundación BBVA, 2007), thus potentiating the social capital of the community (the benefits associated to the cooperation and trust between individuals). If we consider that the social capital has a better potential in high risk contexts and of strategic interdependence between agents, then this is a deciding factor when establishing financial relationships, especially in developing countries (Fundación BBVA, 2007).

The following diagram of Fundación BBVA's (2007) report “Social Capital in Autonomous Communities and Provinces” graphically explains the importance of social networks in the generalization of trust:

Following up with the growing interest in ethical banking of the scientific community, we can assert that the investigation on finances and ethical banking has been largely increased in the past few years. In fact, thanks to this growing interest, new institutions such as the Skoll Centre for Social Entrepreneurship in the Said Business School of Oxford University, created in 2003, or The Institute for Social Banking (ISB) in Bochum, Germany, created in 2006, have emerged (Benedikter, 2012).

Nevertheless, despite the growing interest, it is possible to affirm that the academic research on ethical banking is practically in its initial stages. Previous works acknowledge this, stating that research on ethical banking is largely insufficient, with subjects pending consensus such as the very definition of ethical banking, research pending development regarding the identification of the entities that are a part of this movement, the measurement of the creation of value they provide, the clarification of their objectives, the development of a common methodology that allows measuring their impact that considers the different business models, etc. (Bosheim, 2012).

The report “The Financial System that we Need” expresses the same sentiment. This report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, 2015) states that the next critical step in the evolution towards more sustainable financial systems is the development of a rich study and analysis ecosystem that delves into the theoretical and empirical foundations (UNEP, 2015).

Regarding the research deficit, it is important to note that the affiliation to the ethical banking movement is completely voluntary, without there being any type of specific regulation or public registry that identifies this type of banks. There are not even quality certificates or seals that recognize the social or ethical character of these entities (Sanchis, 2016).

Taking the above into consideration, our research proposal has been developed with the objective of providing these entities with a mechanism that identifies them, is of use as a tool to communicate their main characteristics, grants them more credibility, and builds the confidence of their clients—current and potential—all of which are aspects that should be fully developed for ethical banking to harness its full potential in the future (Alsina, 2002).

In this sense, our contribution entails the definition of the main characteristics of ethical banking and the measurement of their presence in each of the ethical banks identified as such by means of a new index. In this manner, this index will measure the commitment level of an entity with the principles of the ethical banking movement.

To design this index, we have reviewed the available literature as well as the website contents of the ethical banks affiliated to the GABV.

Nevertheless, before designing the index, we researched the evolution and main characteristics of the ethical banking movement in order to provide an adequate theoretical framework to our empirical research. We have highlighted what, in our opinion, is the most relevant information:

- -

The ethical banking movement aims to reverse the progressive disengagement between ethics and economy that has characterized the evolution of the latter (Alsina, 2002). Concretely, ethical banking upholds that money is solely a tool for people to use, but not itself an end (De Castro, 2013); it upholds that the benefit must exist, but that its place is at the end of the chain (Melé, 2009), because the value of money is in the relations that it favours and the good it creates (Biggeri, 2015).

- -

According to the reviewed literature, there are two expressions that have been generally accepted: ethical banking in the bibliography in Spanish and social banking in English. According to some authors, while the ‘social’ adjective refers to the activity in the bank, the ‘ethical’ adjective identifies it more with its purpose (Alsina, 2002). Other terminology that has started to gain relevance with broad acceptance is banking with values, sustainable banking, and even regenerative or alternative banking (GABV, 2015).

- -

As already indicated, the definition of ethical banking has no consensus (Bosheim, 2012). Nevertheless, due to its clarity and conciseness we can emphasize that it is defined as the bank that pretends to achieve a positive change in people and the environment through banking activity (Weber & Remer, 2011). In this sense, it is important to stress that all entities that belong to the ethical banking movement understand money not as an end, but as a tool to improve the quality of life of people, so that with its use we can obtain a greater impact on human development (De Clerk, 2009).

- -

We obtained the characteristics of the entities that considered themselves ethical mainly from the definition of the ISB, which includes a consensual list of all its members. We have added the characteristics from the available reviewed literature to this list in order to obtain a relation of characteristics that is as complete as possible. It is presented further on.

The methodology used to address our intended quantification is that of similar previous research works: index construction methodology and content analysis methodology.

It should be stressed that the research of ethical banking is practically in its initial stages and above all is incomplete. Therefore, the empirical studies of the same are very limited, with one work from 2003 standing out, which addresses the space that ethical banking could occupy from a marketing perspective (San Emeterio & Retolaza, 2003), and the work by San José and Retolaza (2007) to contrast the differences between ethical banking and the rest of the banking entities.

This last work, which is closer to ours, proposes the elaboration of a new index, the Radical Affinity Index (RAI), as a quantitative indicator of the ethical commitment of a financial entity of any type. This index is built on four synthetic indicators: transparency, added social value of the assets, the demand of guarantees, and participation in the decision making of all interest groups (San José & Retolaza, 2007). Each indicator includes a series of variables that indicate different levels of ethical commitment, with which they intend to conclude the existing differences between ethical and traditional banking.

It is worth noting that the RAI has been used in the works of San José, Retolaza, & Gutiérrez-Goiria (2011), Herden (2012), and Bosheim (2012). However, in our case, we have opted to build a new index, though it is based on the RAI methodology for the following reasons:

- -

Divergence in the objectives: the RAI is focused on locating the differences between ethical banking and traditional banking, whereas our objective is to quantify the ethical and social commitment of the entities that belong to the ethical banking movement.

- -

Restrictive concept of ethical banking: the four indicators of the RAI are based on a theoretical framework that emphasizes the variables selected for their design and which, in our opinion, leave out other important variables. We understand that with this, the RAI comes down to a certain model of ethical banks, which, in our opinion, invalidates it for our objective, which is to use a flexible tool that makes it possible to analyze ethical banking in all its diversity, considering that this movement comprises very different realities and business models (Sunyer & Alsina, 1999) (GABV, 2015).

That being said, it was decided to create a new index called SEBI (Social and Ethical Banking Index) to measure the commitment of each ethical bank with the principles of ethical banking and, subsequently, to elaborate a ranking of ethical banks with the results obtained.

The methodology applied in the quantification of the variables is based on the content analysis, a technique that is used in scientific research to systematize information by applying Berelson's classic definition (1952): a research technique for the objective, systematic, and quantitative description of the content of the communications in order to interpret it (Espín, 2002).

In our case, we will carry out the analysis of the content of the websites of the entities that belong to the GABV, whose associates comprise the target population of our analysis, considering that the GABV is the most relevant network of ethical banks with principles that completely adjust to the objectives of our work.

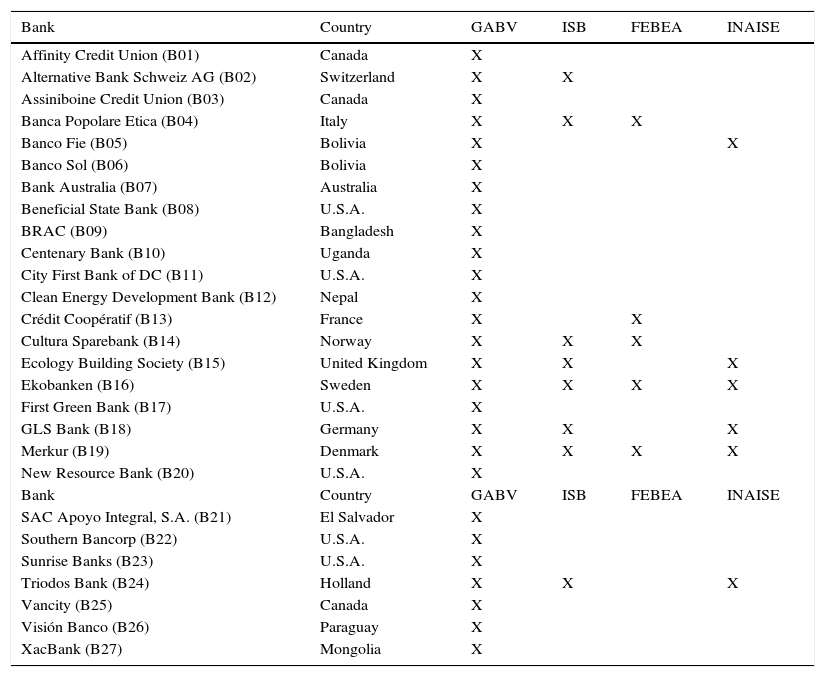

We include a relation of the analyzed banks in Tables 1, 2 and 4–7. A total of 27 banks: 9 from Europe, 10 from developed countries in the rest of the continents (U.S.A, Canada and Australia), and 8 from developing countries.

Target population for analysis: banks members of the GABV.

| Bank | Country | GABV | ISB | FEBEA | INAISE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Credit Union (B01) | Canada | X | |||

| Alternative Bank Schweiz AG (B02) | Switzerland | X | X | ||

| Assiniboine Credit Union (B03) | Canada | X | |||

| Banca Popolare Etica (B04) | Italy | X | X | X | |

| Banco Fie (B05) | Bolivia | X | X | ||

| Banco Sol (B06) | Bolivia | X | |||

| Bank Australia (B07) | Australia | X | |||

| Beneficial State Bank (B08) | U.S.A. | X | |||

| BRAC (B09) | Bangladesh | X | |||

| Centenary Bank (B10) | Uganda | X | |||

| City First Bank of DC (B11) | U.S.A. | X | |||

| Clean Energy Development Bank (B12) | Nepal | X | |||

| Crédit Coopératif (B13) | France | X | X | ||

| Cultura Sparebank (B14) | Norway | X | X | X | |

| Ecology Building Society (B15) | United Kingdom | X | X | X | |

| Ekobanken (B16) | Sweden | X | X | X | X |

| First Green Bank (B17) | U.S.A. | X | |||

| GLS Bank (B18) | Germany | X | X | X | |

| Merkur (B19) | Denmark | X | X | X | X |

| New Resource Bank (B20) | U.S.A. | X | |||

| Bank | Country | GABV | ISB | FEBEA | INAISE |

| SAC Apoyo Integral, S.A. (B21) | El Salvador | X | |||

| Southern Bancorp (B22) | U.S.A. | X | |||

| Sunrise Banks (B23) | U.S.A. | X | |||

| Triodos Bank (B24) | Holland | X | X | X | |

| Vancity (B25) | Canada | X | |||

| Visión Banco (B26) | Paraguay | X | |||

| XacBank (B27) | Mongolia | X |

Source: Own elaboration based on the websites of GABV, ISB, FEBEA and INAISE.

The same table indicates the membership, where applicable, to the ISB, to the European Federation of Ethical and Alternative Banks (FEBEA), and/or to the International Association of Investors in the Social Economy (INAISE), understanding that it is an interesting fact to know the membership to other networks for two reasons: (1) it reveals the importance that the ethical banking movement places on networking, and (2) it makes it possible to know the relevance of each of the networks, though taking into consideration that the GABV and the INAISE are international networks, whereas the ISB and FEBEA are European organizations.

It should be noted that this selection is not as complete as we would like it to be, given that it does not include those ethical banks that do not belong to this network, as is the case of the most well-known ethical bank in the world: the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh, whose founder, Muhammad Yurus, has won a Nobel Peace Prize and the Princess of Asturias Award. Despite this limitation due to a lack of databases, certificates, or regulations that unequivocally identify ethical banks, we have selected the membership to the GABV as the best criteria for identification due to its clarity and easy application.

Once the target population has been defined for the study, we proceeded to present the design of the SEBI index as a measure of the commitment with the principles of ethical banking.

Creation of the SEBI index: design of indicators, pre-test and delimitation of variablesAs outlined above, the design of the SEBI index departs from the work done by San José and Retolaza (2007), adding the rest of the defining characteristics of ethical banking—according to the literature reviewed—to the variables considered by these authors, mainly those contained in the definition of the ISB (2011) due to their comprehensiveness. All of them will be taken into consideration in the design of our index.

We list said characteristics below. In order to facilitate the understanding of the design of the SEBI index, which will be presented further ahead, the characteristics are codified with the letter “C” and a reference number by list order.

- -

C1: Negative Screening: negative social, cultural, ecological and ethical criteria apply to rule out possible negative impacts on sustainability and general welfare. Prior to the financial analysis.

- -

C2: Positive Screening: positive social, cultural, ecological and ethical criteria apply to support projects with positive impacts on sustainability and general welfare. Prior to the financial analysis.

- -

C3: They offer financial services to those excluded from the financial system.

- -

C4: They encourage public debate on the main challenges of our world.

- -

C5: They deal with a very large group of stakeholders or interest groups.

- -

C6: They practice and make public the values that inspire all of their activities.

- -

C7: They consider sustainability to be a core value.

- -

C8: They pay special attention to human rights and solidarity.

- -

C9: The approach of their business is humane and humanizing.

- -

C10: The forms of government and their organizational structures are based on participation.

- -

C11: They have legal structures that prevent the dependency on particular pervasive interests.

- -

C12: They defend the equality of opportunities for all employees.

- -

C13: They offer their clients the possibility to make donations to different organizations and projects.

- -

C14: They carry out extensive work to raise awareness.

- -

C15: They reject profit maximization as an end itself, as well as speculative activity.

- -

C16: They consider economic benefit as a means to achieve social development and to defend the environment, and not as an end itself.

- -

C17: Triple bottom line approach: aims for a triple social, environmental and financial benefit.

- -

C18: They offer maximum transparency of all the available information.

- -

C19: They are also transparent with regard to the development of their business model.

Having presented the characteristics that will be considered in the design of the variables that comprise the synthetic indicators of the SEBI index, it is worth explaining what the available literature defines as synthetic indicator.

Concretely, a synthetic indicator can be defined as a function of a set of variables, each one of which contributes to the quantification of a certain aspect of the concept for which it is necessary to quantify its magnitude (López, Sánchez, & e Iglesias, 2003). The selection of the initial indicators, the mode of standardization and the assessment of the information, as well as the subjective aspects of the synthetic measure's definition is left to the discretion of the analyst (Pérez et al., 2009).

In this manner, it can be stated that there is no specific methodological procedure that is the most accurate for the creation of a synthetic indicator, but rather that the chosen procedure will depend on the analyst and the objective of his study (Pérez et al., 2009).

Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that an indicator must be based on available data that is reliable and easy to measure, that must be easy to understand not only by experts, and that must focus on practical and clear aspects (Rivas & Magadán, 2007).

To design our indicators and the SEBI index, we have taken the above into consideration, prioritizing the reliability of the data—all of which are available on the websites of the target banks of this study—as well as the simplicity of measurement and understanding, following the example of the only similar previous empirical study found in the available literature (San José et al., 2011).

Said study reflects the greater importance of the transparency indicators and the allocation of assets in social projects, as differentiating features of ethical banking with regard to traditional banking. These two indicators have been selected for the design of our index, adding two more indicators with the aforementioned objective of including all the diversity of ethical banks along with their already outlined characteristics.

In this manner, the SEBI index is calculated by adding four indicators, each of which synthetizes the quantification of designed variables considering the characteristics of ethical banking (C1 to C19), as will be later detailed.

We present below the proposed indicators with reference to authors who consider their relevance when defining a bank as ethical:

- -

Indicator 1 (I1): Radical transparency, both of the financial information and of every activity of the bank (Alsina, 2002; Bosheim, 2012; Buttle, 2007; De Castro, 2013; De la Cruz, Sasia, & Garibi, 2011; De la Cuesta and Del Río, 2001; GABV, 2015; Paulet, Parnaudeau, & Relano, 2015; Potts, 2014; San José and Retolaza, 2007; Sasia, 2008).

- -

Indicator 2 (I2): Social, cultural, and/or environmental impact, and ethical assessment of the project whose financing is requested, prior to the obligatory financial analysis, as part of the triple benefit search strategy: social, environmental and financial (Alsina, 2002; Benedikter, 2012, Bosheim, 2012; Buttle, 2007; De Castro, 2013; De la Cruz et al., 2011; Ferreira et al., 2016; GABV, 2015; Goyal and Joshi, 2011; Herden, 2012; Melé, 2009; Paulet et al., 2015; Potts, 2014; San José and Retolaza, 2007; Sasia, 2008; Scheire and Maertelaere, 2009; Sierra and Londoño, 2008).

- -

Indicator 3 (I3): Organizations with an inclusive corporate governance and participative, humane and sustainable organizational structures that facilitate and promote the involvement and commitment with the values of ethical banking of their associates, employees and the rest of the interest groups or stakeholders (GABV, 2015; Herden, 2012; Melé, 2009; Potts, 2014; San Emeterio and Retolaza, 2003; Sasia, 2008).

- -

Indicator 4 (I4): Awareness-raising efforts on the urgent need to achieve a more humane and sustainable world (Alsina, 2002; Ballesteros, 2002; De Castro, 2013; De la Cruz et al., 2011; GABV, 2015; Paulet et al., 2015; Potts, 2014; Sasia, 2008; Scheire and Maertelaere, 2009; Sierra and Londoño, 2008).

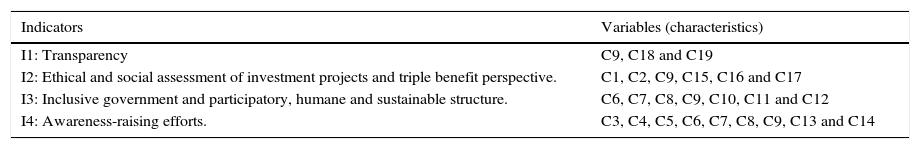

As stated above, the aforementioned indicators are calculated by quantifying the variables or characteristics of the listed ethical banks, according to the assignment presented in Table 2 and with the objective of including in our quantification the entirety of the identified characteristics. As previous clarification, we note that the humane and humanizing approach of the business model (C9) is the only characteristic considered transversal with regard to all the variables.

Assignment of the characteristics of ethical banks to the indicators of the model.

| Indicators | Variables (characteristics) |

|---|---|

| I1: Transparency | C9, C18 and C19 |

| I2: Ethical and social assessment of investment projects and triple benefit perspective. | C1, C2, C9, C15, C16 and C17 |

| I3: Inclusive government and participatory, humane and sustainable structure. | C6, C7, C8, C9, C10, C11 and C12 |

| I4: Awareness-raising efforts. | C3, C4, C5, C6, C7, C8, C9, C13 and C14 |

Source: Own elaboration.

For the delimitation of the variables included in each indicator of the index, we have also taken into consideration the pre-test applied in November 2012 to the Spanish subsidiary of Triodos Bank, one of the most important ethical banks in the world and the most important in Europe (Bosheim, 2012). Furthermore, we have also taken into consideration the information contained in the websites of the target ethical banks of our study.

As mentioned above, the design of the SEBI index has focused on favouring the simplicity of the measurement and understanding of the results obtained. With this criterion, we depart from the hypothesis that all our indicators and variables have the same importance when considering a bank as ethical. This design is endorsed by a great portion of the works on the creation of synthetic indicators that use one-dimensional linear projections that generate weighted averages of simple indicators.

In fact, the methodology most applied is the one that uses weight in the same proportion and adds information through a sum, due to its low operational difficulty and the associated simplicity in the interpretation of the results. The assessment and sum are usually done in successive levels, so that first the assessment and sum of a series of variables is done to create the sub-indicators regarding a certain dimension to then obtain the synthetic indicator through the sum of the sub-indicators (Domínguez, Blancas, Guerrero, & González, 2011).

This simple aggregation methodology can be used when the analyst seeks to obtain a computationally simple synthetic measure that is easy to interpret (Domínguez et al., 2011), which, as already stated, is the case for the design of our index.

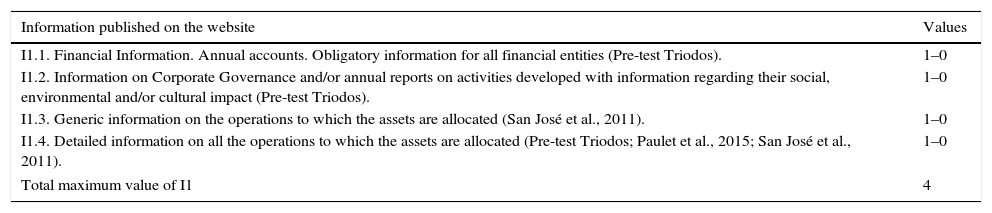

In view of the above, and striving for simplicity and easiness of interpretation and dissemination, each indicator has been assigned a maximum assessment value of 4, which is divided in a linear fashion between its variables, as shown in Tables 3–6. This way, a result based on a value of 16 is obtained, which, to obtain the value of the SEBI index will be turned into a base value of 10 to favour a more intuitive understanding and facilitate its comprehension and dissemination.

Indicator I1 design. Transparency quantification.

| Information published on the website | Values |

|---|---|

| I1.1. Financial Information. Annual accounts. Obligatory information for all financial entities (Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| I1.2. Information on Corporate Governance and/or annual reports on activities developed with information regarding their social, environmental and/or cultural impact (Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| I1.3. Generic information on the operations to which the assets are allocated (San José et al., 2011). | 1–0 |

| I1.4. Detailed information on all the operations to which the assets are allocated (Pre-test Triodos; Paulet et al., 2015; San José et al., 2011). | 1–0 |

| Total maximum value of I1 | 4 |

Source: Own elaboration.

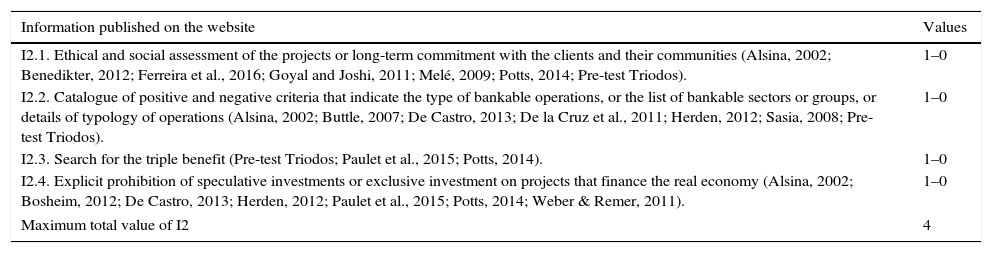

Indicator I2 design. Quantification of the ethical and social assessment and the search for the triple benefit: social, ecological and economic.

| Information published on the website | Values |

|---|---|

| I2.1. Ethical and social assessment of the projects or long-term commitment with the clients and their communities (Alsina, 2002; Benedikter, 2012; Ferreira et al., 2016; Goyal and Joshi, 2011; Melé, 2009; Potts, 2014; Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| I2.2. Catalogue of positive and negative criteria that indicate the type of bankable operations, or the list of bankable sectors or groups, or details of typology of operations (Alsina, 2002; Buttle, 2007; De Castro, 2013; De la Cruz et al., 2011; Herden, 2012; Sasia, 2008; Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| I2.3. Search for the triple benefit (Pre-test Triodos; Paulet et al., 2015; Potts, 2014). | 1–0 |

| I2.4. Explicit prohibition of speculative investments or exclusive investment on projects that finance the real economy (Alsina, 2002; Bosheim, 2012; De Castro, 2013; Herden, 2012; Paulet et al., 2015; Potts, 2014; Weber & Remer, 2011). | 1–0 |

| Maximum total value of I2 | 4 |

Source: Own elaboration.

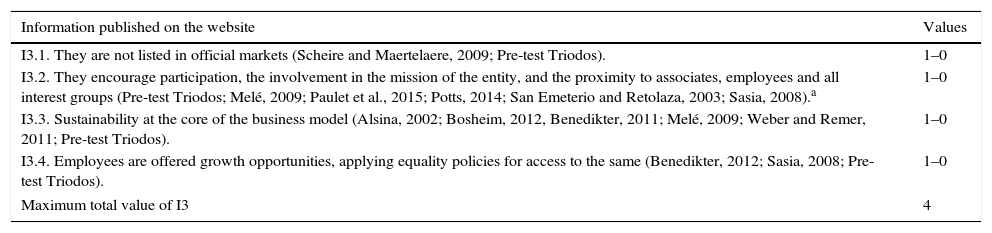

Indicator I3 design. Quantification of the inclusive corporate governance and participatory, humane and sustainable structure.

| Information published on the website | Values |

|---|---|

| I3.1. They are not listed in official markets (Scheire and Maertelaere, 2009; Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| I3.2. They encourage participation, the involvement in the mission of the entity, and the proximity to associates, employees and all interest groups (Pre-test Triodos; Melé, 2009; Paulet et al., 2015; Potts, 2014; San Emeterio and Retolaza, 2003; Sasia, 2008).a | 1–0 |

| I3.3. Sustainability at the core of the business model (Alsina, 2002; Bosheim, 2012, Benedikter, 2011; Melé, 2009; Weber and Remer, 2011; Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| I3.4. Employees are offered growth opportunities, applying equality policies for access to the same (Benedikter, 2012; Sasia, 2008; Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| Maximum total value of I3 | 4 |

Source: Own elaboration.

Examples of possible practices: publication of biographies and contact data of the members of the governing bodies and main executives, Rochdale principles, participatory and periodic events, open communication channels to associates and stakeholders, publication of documents of interest for associates and stakeholders in addition to the annual report and/or corporate governance report (on events, legislation, developments of relevance, etc.).

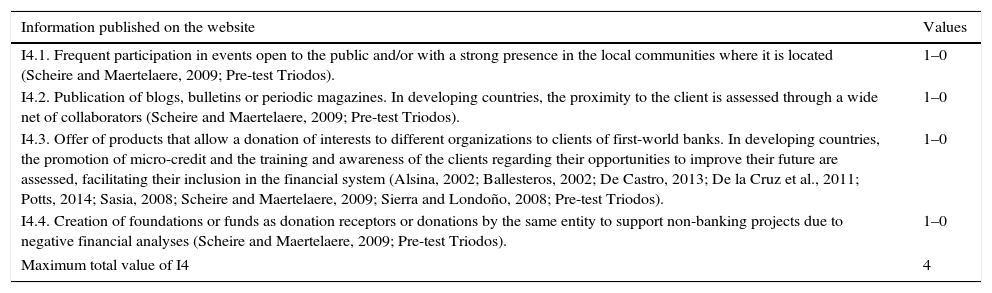

Indicator I4 design. Quantification of the awareness-raising efforts.

| Information published on the website | Values |

|---|---|

| I4.1. Frequent participation in events open to the public and/or with a strong presence in the local communities where it is located (Scheire and Maertelaere, 2009; Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| I4.2. Publication of blogs, bulletins or periodic magazines. In developing countries, the proximity to the client is assessed through a wide net of collaborators (Scheire and Maertelaere, 2009; Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| I4.3. Offer of products that allow a donation of interests to different organizations to clients of first-world banks. In developing countries, the promotion of micro-credit and the training and awareness of the clients regarding their opportunities to improve their future are assessed, facilitating their inclusion in the financial system (Alsina, 2002; Ballesteros, 2002; De Castro, 2013; De la Cruz et al., 2011; Potts, 2014; Sasia, 2008; Scheire and Maertelaere, 2009; Sierra and Londoño, 2008; Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| I4.4. Creation of foundations or funds as donation receptors or donations by the same entity to support non-banking projects due to negative financial analyses (Scheire and Maertelaere, 2009; Pre-test Triodos). | 1–0 |

| Maximum total value of I4 | 4 |

Source: Own elaboration.

As presented above, the measurement of the variables is done based on the information published on the websites of the analyzed entities, therefore, if the characteristics that comprise the variable to be measured are present then it is granted 1 point, if they are not present it is granted 0 points.

The score of an indicator will result in the addition of the values observed for each of the variables that comprise it, and the SEBI index values for each ethical bank will be obtained from the sum of the value of the four indicators with a base of 10:

According to the formula above, the SEBI value will be between 0 and 10.

It is worth noting that the reason for converting the resulting value from the sum of the indicators to a base of 10 is none other than to provide user-friendly information to facilitate the understanding and dissemination of the results.

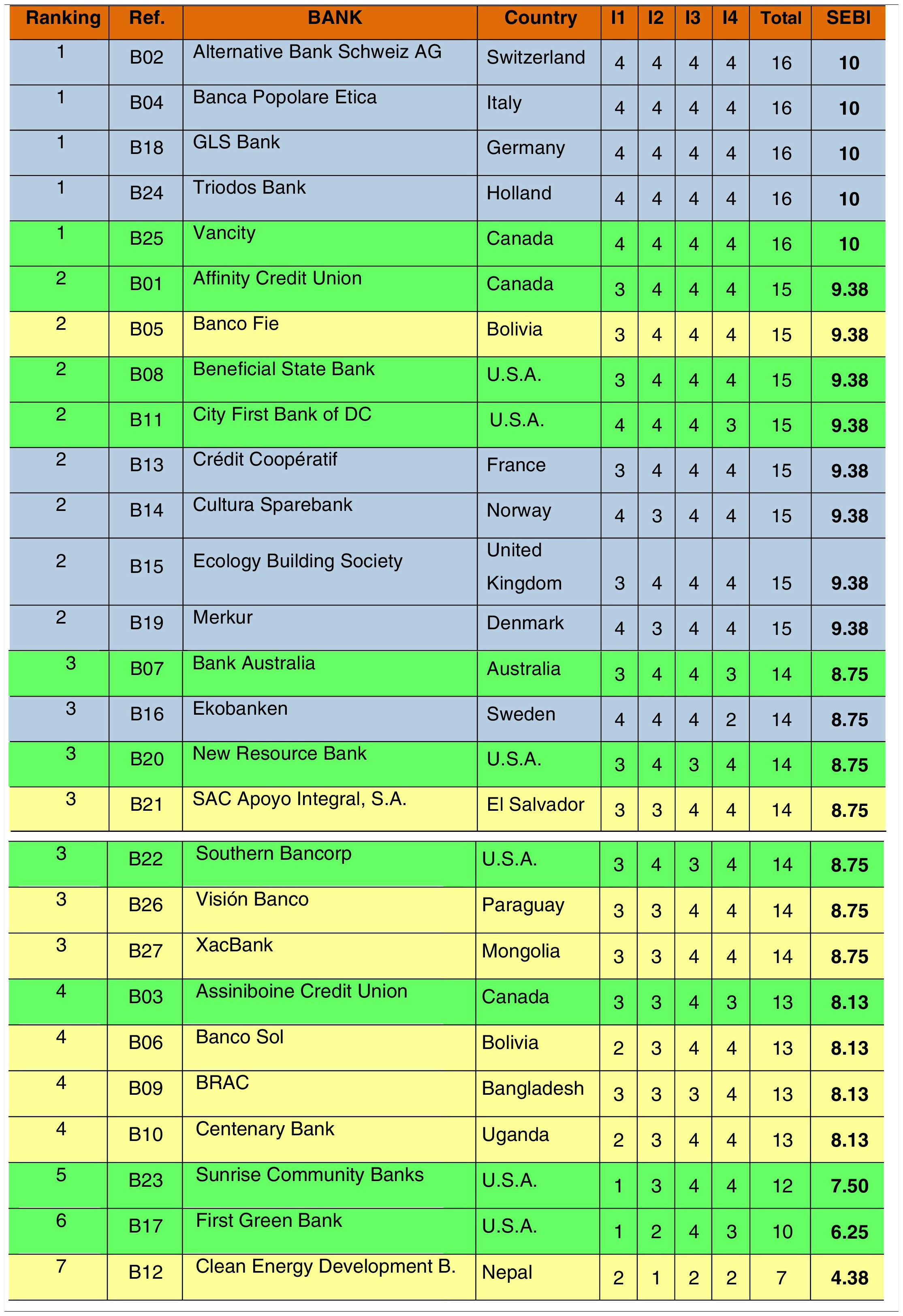

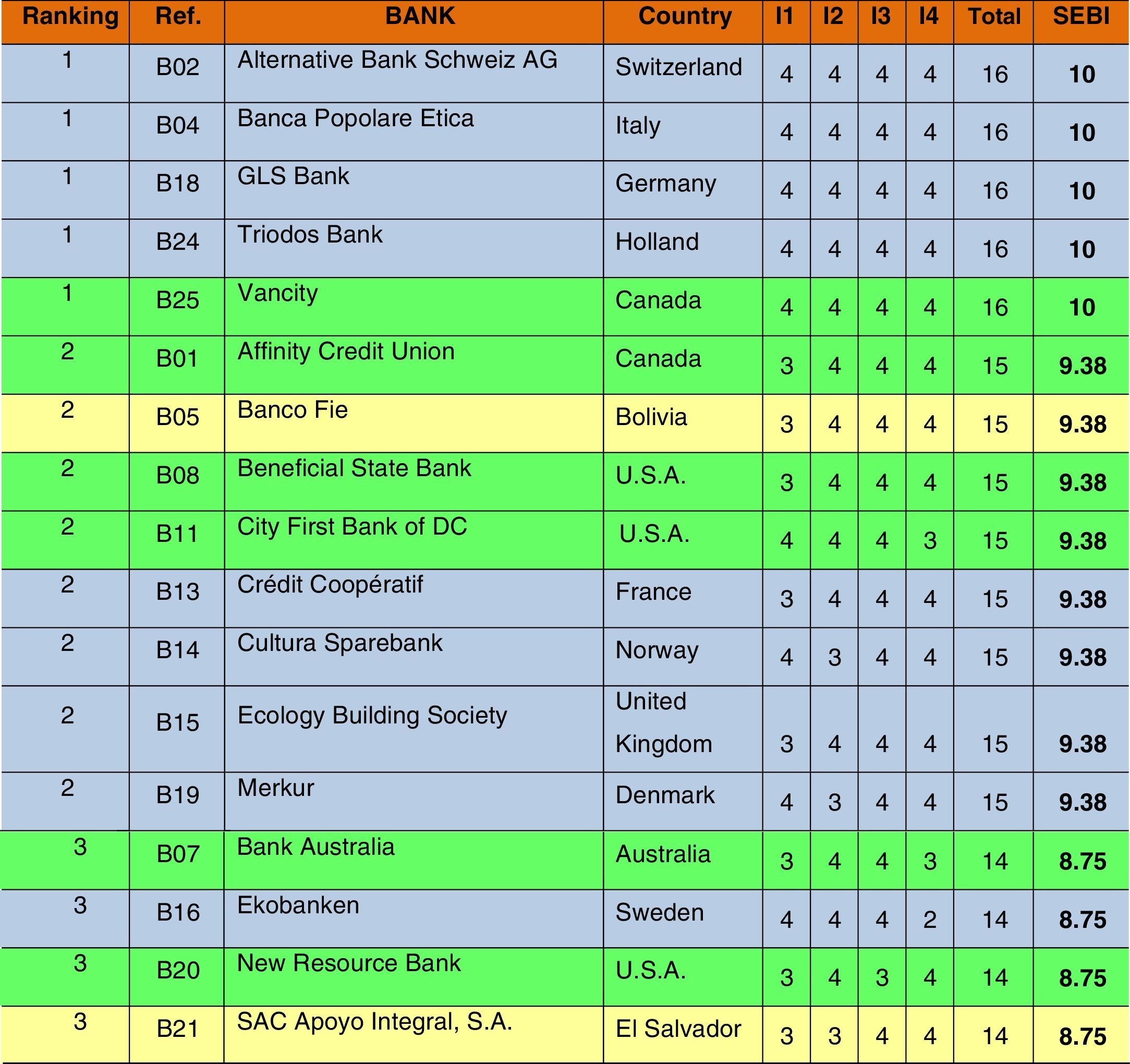

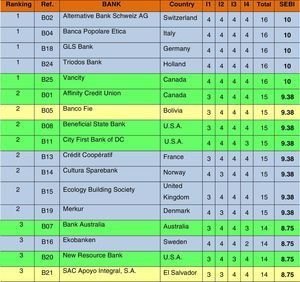

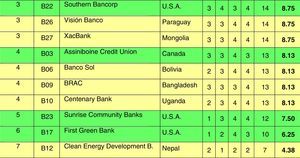

ResultsOnce the websites of the 27 banks of the GABV were reviewed, and having calculated the SEBI index for each of them as previously indicated, we obtained the results presented in Table 7.

From the ranking presented above we can conclude, among others, that:

- -

Of the five entities that rank first place due to achieving the maximum score, four are European and one Canadian.

- -

The seven entities that rank second, with a score of 9.38, did not reach the maximum score due to not informing of the entirety of their investment projects, except for entity B11, which does not have its own foundation or carries out a direct donation of funds, and B14, which does not publish a catalogue of positive and negative criteria on banking activities. Of these eight entities, one of them is from a developing country, four are European, two are from the United States and one is from Canada.

- -

No ethical bank from those that operate in developing countries scores for the publication of the entirety of their investment projects, therefore, in future researches it could be analyzed if this characteristic makes sense for banks that are mainly focused on granting micro-credit in order to make possible the financial inclusion of their target clients.

- -

Raking third, with a score of 8.75, are seven entities, one European, two North-American, one Australian and three from developing countries. Ranking fourth, with a score of 8.13, there is one Canadian entity and three from developing countries. In the fifth position, with a score of 7.50, there is a North-American bank.

- -

The banks that ranked in the last places, B17 and B12, with scores of 6.25 and 4.38, respectively, are located in the United States and Nepal, respectively. These entities have limited scores regarding transparency, given that they do not publish information regarding previous ethical and social assessments of projects that requested financing; furthermore, B12 also obtains a limited score with regard to the information it offers on its awareness-raising efforts.

- -

Regarding the eight analyzed ethical banks from developing countries, we can conclude that all of them, with the exception of B12, rank among the four first positions. And that in these four ranking positions 89% of the 27 banks analyzed are concentrated, scoring between and outstanding (10) and a notably high (8.13) score.

In view of these results, we present below the main conclusions and implications of this research.

ConclusionsAfter analyzing the results of our research in the pages above, we explain the main conclusions that, in our opinion, derive from the same:

- (1)

Ethical Banks, in their diversity, have common characteristics among them. One of our objectives has been to define the common characteristics of all ethical banks. This was achieved due to the revision of the literature and to the information facilitated by the main ethical bank networks: ISB, GABV, FEBEA and INAISE. In short, we have concluded that there are 19 common characteristics that can be categorized into four more general categories:

- (a)

Radical transparency.

- (b)

Search of a triple benefit (social, environmental and economic), which includes the social and environmental assessment of the projects, prior to the financial analysis.

- (c)

Inclusive corporate governance and participatory, humane and sustainable organizational structures.

- (d)

Awareness-raising efforts to extend financial formation, responsible financial consumption and the need to get involved in a humane and sustainable development, both locally and globally.

- (a)

- (2)

The empirical objective of this work has been the measurement of the commitment of banks denominated ethical with the ethical banking movement through the SEBI index. As an important premise, we have taken into consideration that the index should be flexible and allow to quantify all diversity in the spectrum of ethical banks, and that the simplicity in the calculation and interpretation of the results should be paramount in its design.

Taking into consideration that the adherence to the ethical banking movement is entirely voluntary, without presently having any sort of regulations for the same, neither public nor private certification, we have concluded that quantification is extremely relevant as it can provide more credibility to this phenomenon and reinforce the trust of its current and potential clients.

- (3)

We have obtained a ranking of ethical banks through the calculation of the SEBI index for the ethical banks of the GABV. The ranking reveals that the European ethical banking has, in general, the highest level of commitment, though the high level of commitment of the banks in developing countries has also been proven (with the exception of one case) and, in general, the same applies for the high level of commitment of all the banks of the GABV, with 89% of them ranking among the first four positions in the ranking with minimum scores of 8.13.

In our opinion, it is important to stress that the aforementioned conclusions reflect the main contributions of this research with regard to previous works, which have addressed other aspects of the issue, such as the development of an index that compares ethical and traditional banking. Similarly, we understand that the contribution of an ethical bank ranking with a broad definition—that does not exclude any of the characteristics of ethical banking indicated in literature—facilitates the discovery of new and interesting research areas for the future.

In any case, we consider that the possibility to carry out the aforementioned contributions has been facilitated by this recent phenomenon, which in turn makes the scientific literature regarding the same be very limited, with many topics pending consensus such as the very definition of the same.

In the same manner, the youth of the movement has added difficulties to the research. Such as the fact that there are no databases, regulations or available certifications for the identification of ethical banks or the existence of a minimum homogenization criteria, given that the diversity observed in this type of banks is an obstacle that has compelled us to adapt our index to all the casuistry observed. Nevertheless, we understand that this homogenization work can also be an additional contribution, which could be expanded on in the future.

In this sense, we propose some future lines of research that, in our opinion, could be of further interest:

- a)

Analysis of the determining factors of the option for voluntary commitment with ethical banking of the banks affiliated to the phenomenon, based on possible motivations such as crisis, size, and social or environmental commitment.

- b)

Subsequent development of the SEBI index:

- -

In-depth analysis of the possible manifestations of the different variables in ethical banks that operate in developing countries, addressing the special typology of their clients.

- -

Validation of the hypothesis used in this work, regarding the identical weight of variables and indicators, or the proposal of alternative hypotheses analyzing the weight that should be granted to each of the indicators, and of the proposal for the calculation of each indicator based on the variables that comprise it.

- -

- c)

Development of procedures that allow verifying and certifying the affiliation of an entity to the ethical banking movement through the review of all relevant aspects: information, operation, procedures, human resource management, corporate governance, relations with the rest of the interest groups, awareness-raising efforts, etc.

- d)

In light of the fact that a well-known and relevant ethical bank such as the Grameen Bank does not belong to any of the ethical bank networks, we propose, as an added topic, the analysis of the costs and benefits that the affiliation of an ethical bank to the different networks that comprise it.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.