In this paper, organizational social capital (OSC) is conceived as a particular organizational competency determined by the convergence of three relational assets (orientation towards collective goals, mutual trust and shared values), which allows organizations that have it, to coordinate and cooperate for mutual benefit and increased performance. Five case studies of a technology-based small enterprise (TBSE) and four Technology-based Micro Enterprises (TBME) were performed to answer the main research question: How to operationalize the concept of OSC to understand and manage it more effectively? From the empirical phase, the following results were obtained: first, an analysis model for the formation of OSC that graphically presents the adoption of a multilevel analysis (individual, team and organizational). Second, a set of signals of opportunity allowed to identify the presence and characterize the role of six key variables (relational competence, commitment, work environment, complementarity of roles, opportunities for communication and strategic orientation) in the formation of OSC.

En este artículo, el capital social organizativo (CSO) es concebido como una competencia organizativa determinada por la convergencia de tres activos relacionales (la orientación hacia objetivos colectivos, la confianza mutua y los valores compartidos), la cual permite a las organizaciones que la poseen coordinarse y cooperar para el beneficio mutuo y el aumento del desempeño. Cinco estudios de caso de una Pequeña Empresa de Base Tecnológica (PEBT) y de cuatro Microempresas de Base Tecnológica (MEBT) fueron efectuados para responder la pregunta de investigación principal: ¿Cómo operacionalizar la noción de CSO para comprenderla y administrarla más efectivamente? De la fase empírica fueron obtenidos los siguientes resultados: primero, un modelo de análisis de la formación de CSO que presenta gráficamente la adopción de un análisis multiniveles (individual, de equipo y organizativo). Segundo, un conjunto de señales de oportunidad permitió identificar la presencia y caracterizar el rol de seis variables determinantes (competencia relacional, compromiso, ambiente de trabajo, complementariedad de roles, espacios de comunicación y orientación estratégica) en la formación de CSO.

In this paper, the formation of Organizational Social Capital (OSC) in the Technology-based Micro Enterprises (TBME) is analyzed from the identification, characterization and illustration of a set of determining variables and signals called of opportunity. The interest of the authors is in strategy, specifically on choosing, building or obtaining sustainable competitive advantages. Among the various existing theories in strategy, the authors adhere to the theory of competitiveness based on resources (Penrose, 1995, Wernerfelt, 1984, Barney, 1991, Amit & Schoemaker, 1993). This theory includes various approaches (Eisenhardt & Santos, 2002; Acedo, Barroso & Galan, 2006; Desreumaux, Lecocq & Warnier, 2009), however, it can be said that it emphasizes on the strength of internal resources and competencies of an organization to promote and guide the definition of durable competitive advantages. The authors consider that OSC is part of the organizational skills that can become distinctive and can generate value.

The basic notion of this research, social capital (SC), had its origins in sociology. Indeed, in the mid-1980s this notion is beginning to be recognized and popularized by the contributions of Bourdieu (1986) and Coleman (1988). In this concept, the term “capital” is used metaphorically. The metaphor emphasizes that social relationships are important, valuable, and are an investment with returns, similarly to the manner of other types of capital.

The concept of SC has been applied by different authors to different levels: individuals, communities, countries and organizations. This research is placed in the latter group and, hence, the review of the realized literature and formulated proposals are directed exclusively to the world of organizations.

The use of the concept of SC within organizations is recent. Indeed, it was the founder article of Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) that stimulated the discussion on the subject; soon, Leana and Van Buren (1999) used the term OSC itself for the first time. From that moment, different conceptualizations have been proposed, and its revision allows jumping to the conclusion that there is no consensus on the nature or on the components or on the boundaries of the OSC. With regard to this notion, the same phenomenon that characterized the founding notion of SC is then identified: it is only possible to distinguish a “genotype” of SC linked to different “phenotypes”, i.e., to an impressive number of definitions and applications that grows through time (Adam & Ronce¿vic¿, 2003).

In this research, the OSC is defined as the organizational competency determined by the convergence of three relational assets constructed within a durable and appropriate internal and external network of social relations, which allows the holding organization to coordinate and cooperate for mutual benefit and improvement of their performance.

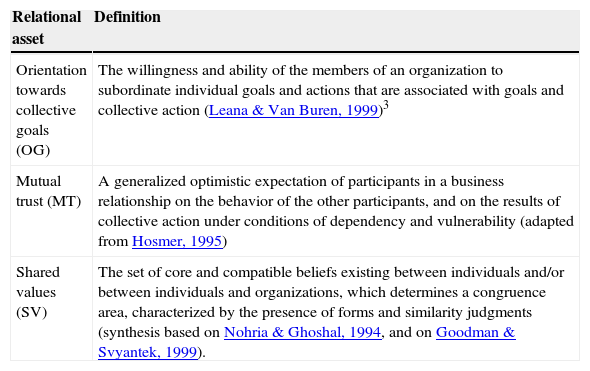

The three relational assets1 constituting the OSC are shown in Table 1.

The relational assets that constitute OSC.

| Relational asset | Definition |

|---|---|

| Orientation towards collective goals (OG) | The willingness and ability of the members of an organization to subordinate individual goals and actions that are associated with goals and collective action (Leana & Van Buren, 1999)3 |

| Mutual trust (MT) | A generalized optimistic expectation of participants in a business relationship on the behavior of the other participants, and on the results of collective action under conditions of dependency and vulnerability (adapted from Hosmer, 1995) |

| Shared values (SV) | The set of core and compatible beliefs existing between individuals and/or between individuals and organizations, which determines a congruence area, characterized by the presence of forms and similarity judgments (synthesis based on Nohria & Ghoshal, 1994, and on Goodman & Svyantek, 1999). |

Between different levels of analysis of SC, the organizational level is among the least studied (Bolino, Turnley & Bloodgood, 2002; Payne, Moore, Griffis & Autry, 2011). Additionally, studies employing the concept of OSC are quite diversified and concentrate more on the consequences of an organization having it than on its nature, its determinants, its contents or its dangers. Most of the previous investigations analyzed dyadic relationships: a causal variable and an outcome variable, the OSC assuming either role. However, many details about operationalization of this notion can still be clarified and deepened. Consequently, the research questions of this paper are the following: a) how to operationalize the concept of OSC to understand it and manage it in a more effective way?; b) how to identify the variables determining the formation of OSC in a TBME?2

Literature ReviewSince the late 1990s, several authors have conducted research on a number of aspects that can be categorized as follows: the characteristics of the OSC (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Tsai & Ghoshal, 1998; Leana & Pil, 2006); its determinants (Leana & Van Buren, 1999; Cohen & Prusak, 2001; Adler & Kwon, 2002; Bolino et al., 2002. Somaya, Williamson & Lorinkova, 2008; Nkakleu, 2009; Saparito & Coombs, 2013; Pastoriza & Arino, 2013); the process (Al Arkoubi & Davis, 2013), the stages of its formation (Anderson & Jack, 2002), its effects (Cooke & Wills, 1999; Yli-Renko, Autio, Sapienza & Hay, 2001; Watson & Papamarcos, 2002; Bilhuber, 2009); its contributions to entrepreneurship (Baron & Markman, 2000; Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Vieira Borges Jr., 2007; Gedajlovic, Honig, Moore, Payne & Wright, 2013; Kreiser, Patel & Fiet, 2013) and to entrepreneur orientation (De Clercq, Dimov & Thongpapanl(2013); its contributions to knowledge management (Greve & Salaff, 2001; Landry, Amara & Lamani, 2002; McElroy, 2002; Inkpen & Tsang, 2005; Weber & Weber, 2007;Exposito, 2008; Rhodes, Lok, Hung & Fang, 2008; Alguezaui & Filieri, 2010; Gooderham, Minbaeva & Pedersen, 2011;); finally, how to measure it (Spence, Schmidpeter & Habish, 2003, Baret & Soto, 2004; Sherif, Hoffman & Thomas, 2006; Oh, Labianca & Chung, 2006).

We adopted the name “OSC” as proposed by Leana and Van Buren (1999) and by Pennings and Lee (1999). Concerning its role in the domain of strategic management, we adhered to the statement of Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998), whereby the OSC is a facilitator of the process of knowledge creation. In addition, our definition of OSC is inspired by Esser (2008) who conceived the three systems (control, trust and moral) that fully match the three relational assets that constitute the OSC.

Regarding the variables that compose the OSC, some authors have established certain relations that serve as a background for this research. As Baron and Markman (2000) noted, the “social skills” of the entrepreneur are sources used to obtain resources for his/her organization. Adler and Kwon (2002) highlighted the non-structural elements that are necessary for the formation of SC: opportunity, motivation and ability. Bolino et al. (2002) sustained the relation between the behavior of employees and the formation of OSC. Watson and Papamarcos (2002) emphasized on the “commitment” variable and its role in the formation of OSC. Finally, Bilhuber (2009) illustrated the complementary nature between human capital and OSC.

Among the different levels of studies of SC, the organizational level (the OSC) is the least studied (Bolino et al., 2002; Payne, Moore, Griffis & Autry, 2011) and, consequently, the overview of literature on the subject still appears to be very fragmented. Most of the studies conclude that OSC is an independent variable that produces certain positive effects on companies, or a dependent variable on the action of a determinant factor. These cause-effect analyses have corroborated many hypotheses about the existence of specific bivariate correlations. However, it is possible to discern that, in practice, the formation of OSC cannot be the result of the action of a variable. As a complex notion, the OSC is a multidimensional concept whose determinants and indications remain unclear and undiscussed.

From the perspective of those in research fields, studies about OSC have been primarily conducted in large and medium enterprises (e.g. Cohen and Prusak (2001)), and this verification appears to coincide with the assertions of Marchesnay (2003). According to this author, social science research, particularly in management science, ignores in a large part small businesses whose number is nevertheless dominant in most countries of the world.

We support the perspective of the idea about the specificity of small business management and, by extension, of very small businesses (VSB) (Marchesnay, 2003; Torrès, 2003; Foliard, 2010), given that the problems do not emerge with the same intensity in companies of different sizes. Accordingly, in our further studies about VSB, our beliefs in understanding the motivation in developing and strengthening the OSC were supported, as well as the existence of determinants and indications of this capital, which are influenced by the size of the company.

Design of the ResearchWe chose the case studies as a strategy to access the field of research, and as a tool for theory building (Einsenhardt, 1989, Yin, 1994; Bonache, 1999; Hlady Rispal, 2002, David, 2003, Gerring, 2004). The case studies adopted a qualitative approach to analyze the content of the OSC.

The case studies were conducted in a technology-based small enterprise (TBSE) and four TBME. Besides their size, this type of enterprises are characterized by being knowledge-intensive, committed to Research, Development & Innovation (RD&I), oriented towards specialized market segments, and belonging to the sectors called “high technology”3 or “new economy”.4 Thus, although different subsectors are represented in the sample, all the selected companies utilize knowledge-intensive and innovative orientation characteristics as common factors.

The research protocol was organized in three stages:

1. Starting situation. Upon reviewing the literature and, based on our own insights, we formulated five initial proposals (Box 1).

Box 1 Initial proposals

The concepts of SC and OSC tend to be very abstract and many TBMEs are not aware of their existence nor their importance for the life of the company. Therefore, it is necessary to create a method to understand the wealth of the OSC attributes in a company based on the knowledge of their daily tasks.

The entrepreneur's SC has an important role in the strategic process for strengthening a TBME.

The entrepreneur can provide their individual SC for the assistance of business activities in aiding the TBME form its own OSC.

Aside from the entrepreneur, there are other important roles in the dynamics of social capital exchange (Román & Smida, 2009).

The variables used to characterize the OSC should be identified. The positive effects of the capital are known, but an ensemble of the variables involved to form the OSC has not been studied thus far.

2. Implementation. The size and type of economic activity determines the limits of targeted business population. The selection of chosen firms then conformed to three criteria: a) companies that attract attention on a local level; b) companies geographically located in the near perimeter within the country where we lived at the time; c) firms in which the entrepreneur or manager agreed to our proposal of participating in the case study.

Sampling was performed following the iterative method suggested by Thiétart & Coll. (1999). Thus, each unit of observation was selected after the collection and analysis of data from the previous unit. Since there are not objectives of comparison between cases, the sequential analysis of companies revealed the construction and reconstruction of the theoretical proposals resulting from this research, until obtaining generalized statements for all the analyzed cases.

3. Intervention. The logistics of conducting the case studies included the following activities: a) identifying the company associated with the population of interest and within the constraints of location; b) contacting the entrepreneur or the manager of the company, explaining the research objectives and signing of the confidentiality agreement; c) preparation of the case study: collecting information about the company and arranging of questionnaires and interview questions; d) conducting interviews (entrepreneur and employees) and other activities of internal data collection; e) information processing: transcribing interviews and content analysis. Simultaneously, while recording the content of the interviews, a list of frequently mentioned variables and signals associated with these variables were created as well as text coding that was entered manually to find corresponding paragraphs for each variable and signal; f) development of case study reports: each case study ended with the preparation of a report.

The case studies were carried out between May 2009 and May 2012 with an average duration of 2.5 months each. The primary source of field information was the in-depth interviews. A total of 43 interviews (average duration of one hour each) were made with the entrepreneurs and a selection of employees. Content analysis supported by the software package Nvivo9® enabled, at the completion of the case studies, to constitute a set of presence signals of the variables determining the formation of OSC.

The Object of the Research: Five Cases Studied

Two Exploratory Cases

1. The “Hipertexto” case

“Hipertexto” is a family enterprise which started operations in May 2004, working in several areas of organizational communication.5 Among them, the development of an e-commerce portal for academic publications, both scientific and cultural, (“La Librería de la U”6) is outstanding. Its performance has earned the company several national awards in the field of digital media. The entry of the company on the eBook market was positioned at the forefront of development and commercialized activities of these potential products at a local and international level. In February 2009, “Hipertexto” signed its most important strategic alliance with the Spanish company “Publidisa.” As part of this alliance, the two companies traded their inventory of books; “Hipertexto” is the official representative of “Publidisa” in Colombia and is the country's leader of the conversion of traditional books into an electronic format.

The founding couple integrated some of their family members into the business; later, they decided to omit the family from the company and hire people without any family ties. In 2009, the company had 15 full-time employees and other persons that provided services and were paid per job.

“Hipertexto” has business relationships with several stakeholders. Its suppliers include university presses, printers, freight companies, freelance professionals and manufacturers of POP marketing products. Its clients include the general public and institutional clients; their partners, on the other hand, include companies like “Publidisa” as well as national and international organizations that support the editorial production.

The content of the interviews in this case indicated some concepts that were frequently mentioned. Five essential characteristics of entrepreneurs were revealed by the key variables of their company's SC in the following: The relational competence of the entrepreneur facilitates the recognition of new business opportunities and increases its credibility; individual work style of the entrepreneur tends to be transmitted to the company's staff which gives it a corporate identity and to improve its reputation among the public; the development of a capacity of delegation for the entrepreneur is a requirement to create autonomous teams; the innovative capacity and the long-term vision of the entrepreneur is both appealing and motivating for the employees and motivates them to do their best in order to achieve success; finally, the forming intention of the entrepreneur and their desire in creating a more qualified team also improves the company's reputation.

2. The “Kirvit” case

In 2001, two founding partners, supported by their families, decided to create “Kirvit” for the production of video games. After initial difficulties, the current owner decided to buy out his partner and move into the production of flight training systems. This equipment, used by private schools of aviation and by the armed forces, are educational tools for pilots in training. The company's products are unique in the national electronic industry and are creating a high interest in both current and potential users as well as in the general public. In 2009, the company won a National Innovation Award in the category of Originality.

In March 2010, there were seven full-time employees (including the two business partners – the owner and his wife). Most of the employees are family members of the owners. This particular composition of employees was the foundation of the company, especially due to the strong commitment of some of its members.

The company's financial difficulties were a consequence of the market constraints: the narrow niche, the high costs of R&D and manufacturing, and a limited purchasing power for a section of the clientele. The company had an inefficient marketing department and did not have a dedicated staff in this area. In financial terms, a vicious circle was created: the limited economic resources slowed the development of other products and did not establish an aggressive marketing strategy.

“Kirvit” stakeholders’ are diverse. For a majority of its products, the company focuses on institutional clients. Its suppliers include the manufacturers of metal structures, simulation engines, printed circuit boards, and distributors of electronic components as well as specialized professionals. The company also maintains inter-organizational relationships with the Technology Development Centre in the electronics sector as well as national organizations that promote R&D (“Colciencias,” “Innpulsa Mipymes), Universities and regulatory agencies such as “Aerocivil” and the “Ministry of Transportation.”

After implementing the interviews in “Kirvit” and working on our reflections about the concept of OSC, we were inclined to use a different approach of analysis. We decided to separate the development process of a new product in order to study the occurrence of a transition from a group of individual-level variables to a set of relational assets that constitute the OSC in a very specific situation. Following our study, we decided on three variables of individual level: relational competence, commitment and individual ethical values. The first variable was taken into account in our first case study and we did not include the others. We identified sufficient evidence of commitment among employees, even from those who do not belong to the family of the founding couple. The information provided by the interviewees also allowed us to identify the ethical values of the entrepreneur that appear and are transmitted to employees in the workplace. Our concept of individual-level variables changed. We did not think only about the entrepreneur but about all the other members of the company.

Modelling and corroboration cases

1. The “Evamed” Modelling case

Our third case study implemented a model that influences the variables in the formation of OSC. On this occasion, we have retained a TBME located in Caen (France). Moving to another country was not a deliberate decision. However, we have respected the characteristics of the studied population that is the TBME.

“Evamed” SAS is a TBME that was created in 2005. This company developed a specialized software in the evaluation of the quality of medical devices. It was the winner of the National Competition for Companies using Innovative Technologies, organized by the Ministry of Higher Education and Research, in 2005 and 2006. To develop its product, the company made significant investments in R&D. It started performing activities within the project “Normandie Incubation.” This organization offered the company the physical space required in addition to training services and support. The company then moved to the incubator “Emergence” due to the expiration of the duration of the authorized period from the organization. In October 2010, “Evamed” received an ISO 9001 certification from the group “TÜV Rheinland.” In the first half of 2011, the company had four full-time employees (including the entrepreneur), an employee who was continuing his higher education studies, another part-time employee and two interns. In addition, three staff recruitment processes were ongoing.

The stakeholders of “Evamed” are numerous. In the group of suppliers, its main relationship is maintained with their internet supplier and the server hosting service. Its clients include the manufacturers of medical devices and healthcare facilities (clinics, hospitals); there is also an extensive network with medical-researchers, certified organizations, professional doctors, the pole of competitiveness TES, research groups, business schools, local incubators and an investment fund (NCI Gestión).

The implementation of the new interviews with the participants of “Evamed” and our reflection about the previous case studies have provided us with the ideas to use the appropriate approach and choose the final route that will guide our research proposal. Two new conjectures define the new pathway: a) the formation of OSC is a multilevel phenomenon where the individual level is involved, though it is not the only existing component; (b) two new levels emerged from our analysis: collective, being represented by each of the two existing working teams at “Evamed,” and organizational, which represents the direction of the company.

2. The “Quidd” Corroboration case

“Quidd”7 is a R&D company specialized in preclinical and clinical optical imaging. Through its composition and its multidisciplinary expertise, the company provides solutions and services for academic and industrial participants in the world of human and animal health. “Quidd” concentrates on two types of innovative and complementary technologies: injectable molecules (called probes) which emit a signal of light that is proportional to a targeted biological phenomenon, as well as detection systems that capture these signals within a living body.

In October 2003, “Quidd” was created with the aid of a 400,000 euro grant awarded to the winner of a national business competition. From its inception, this company envisioned covering the entire chain of certain pathology detection, finding the most suitable biomarker and producing the molecular probe and the optical device to detect them. Chemistry is the core of the company's business that also has significant experience in biology, engineering, optics and image analysis. The multiple disciplines are the strength of the company, but they are also the cause of a diversification effect on the company that exceeds the possibilities for funding.

In September 2009, three small biotech companies opened their new offices in the industrial park “Pharma Parc II” in Val-de-Reuil (France), and “Quidd” has also been established there since late 2010. For the company the move brought the chemistry, biology, and engineering groups together, as well as the Management Department, in one location. In late 2011, the company had nine employees including the General Director.

Clients of “Quidd” include pharmaceutical companies, public research centers, pharmaceutical industry subcontractors and other biotech companies. Among its providers, there are manufacturers of parts and components for assembly of scanning equipment, manufacturers of biomarkers and other chemicals, as well as specialized services. The company also maintains inter-organizational relationships with research centers, laboratories, universities, research groups, and both regional and local promoters of R&D.

The aim of our two corroboration cases is to verify the existence of the six variables used in our analysis model of the different factors in the formation of OSC. The “Quidd” case study gave us different elements to examine. This is a very unique business model that struggled to survive after performing activities that corresponded to R&D centers were instead performed by the current director of the company. The various locations of the company's working teams and the several appointed directors were major obstacles that the company faced during its first seven years of life. However, despite the troubles, the director's relational competence was evident, the general appreciation of the value of the company's mission generated commitment from the workers, the work environment and communication capabilities improved with the physical locations of the groups, the complementary roles of employees of the company was high, and the current General Director (at the time of the study) worked on the strategic orientation of the company.

3. The “Ophtimalia” corroboration case

Four engineers, former-employees of the company NXP,8 had worked for the company several years earlier and met together to work on an R&D project in an ad-hoc discussing group at the Institut de la Vision (Paris). They aspired to develop a system to make a continuous measurement of intraocular pressure. The four engineers left NXP in early September 2009 and they created “Ophtimalia” at the end of September 2009. The spin-off agreement signed with NXP defined, among other aspects, the transfer of ownership of the current project to the new company, a business area that can be rented at low cost on the technological campus Effi-Science,9 along with authorized use of NXP's laboratory equipment for two years. Ophtimalia was winner of the 2009 Competition Enterprise Innovation, organized by Synergia,10 and was the winner of the National Contest of Aiding Innovative Technology Business’ Creation 2010, organized by the Ministry of High Education and Research and Oséo.11

Until May 2012, Ophtimalia held three patents on various components of glaucoma diagnostic systems: one on the glasses and the two remaining on the lenses. At the time, the company began the phase of establishing contracts with all necessary partners according to its production model by integrating themselves in the market with nine employees at the time, two new hires were needed for a short term: a person involved in the legal field and a biologist with the ability to work with sensor tests on the eye.

Ophtimalia's providers include companies specializing in contact lenses, milled plastic, and manufacturers of specialized components: glasses, sensor, electronic subsystem for glasses, recorder and recording hardware and software. Its customers include ophthalmologists, health facilities (clinics and hospitals) and research laboratories. Moreover, the company has inter-organizational relations with the Institut de la Vision (Paris), expert ophthalmologists, certifying authorities, an anonymous industry partner, laboratories and schools of specialized higher education, networks of local entrepreneurs and regional institutions related to innovation.

Different indications of the variables determining the OSC formation were corroborated in the history of Ophtimalia. Relational competence of its partners was based on the vast previous experience and outstanding expertise of the group. The entrepreneurial team and its employees used various methods and working frameworks of both very small and large enterprises. They had a tendency to prefer the TBME and it developed into a dependency of the company to follow this model. From the beginning, the assurance of respect and trustworthiness was a collective perception of a good working environment. Functional complementarity became fundamental to develop the proposed diagnostic system. The partners are engaged in a long-term project that highlights their strategic orientation and its formal and informal opportunities of communication which are defined in Ophtimalia to create a copasetic environment and facilitate information exchange.

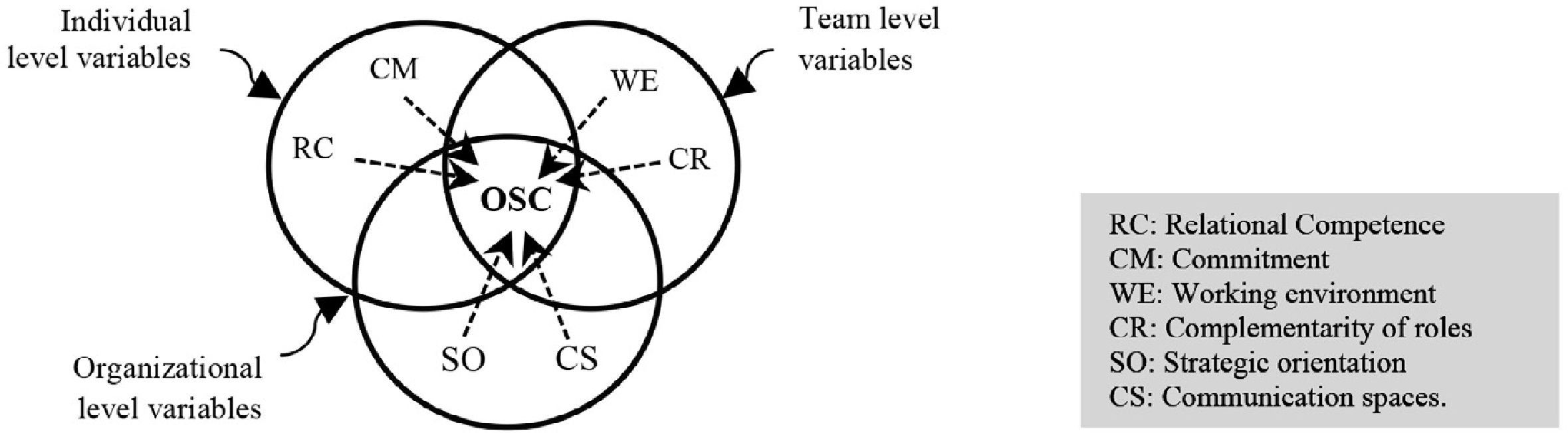

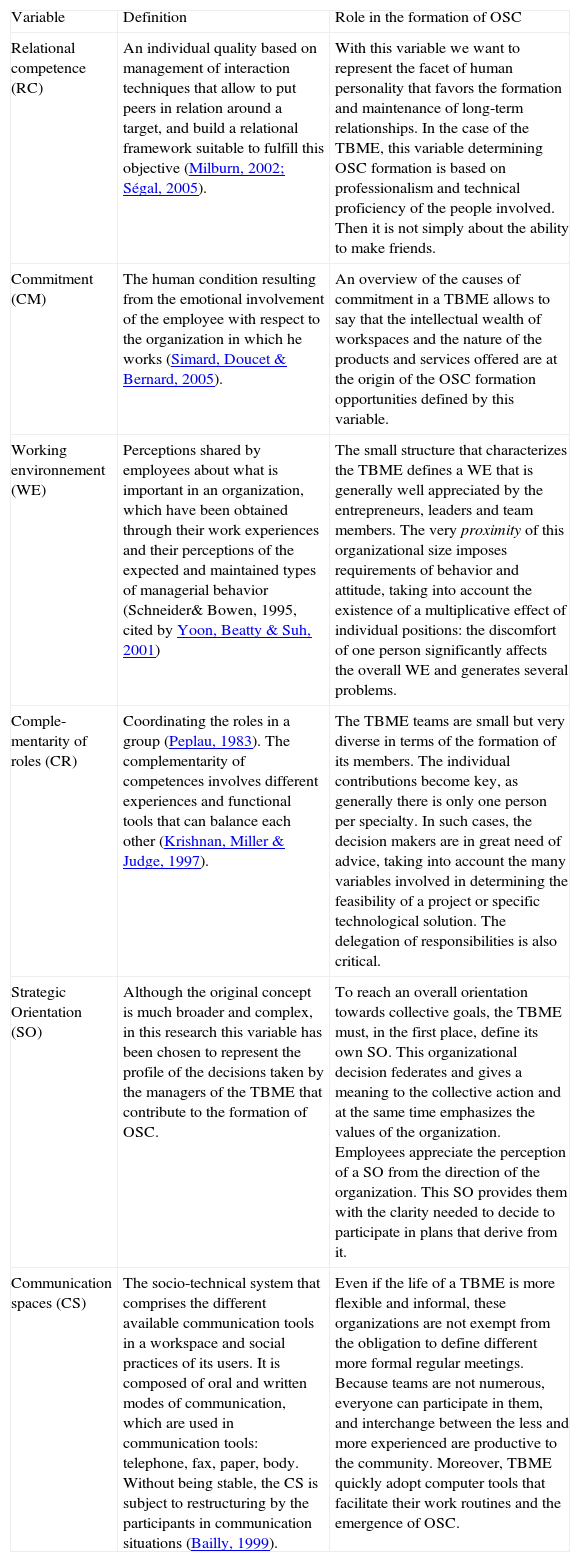

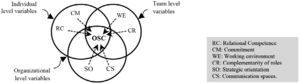

ResultsA first result is a model representing levels and variables chosen to analyze the OSC formation. The variables are: relational competence and commitment for the individual level, working environment and complementarity of roles for the team level, and strategic orientation and communication spaces for the organizational level (figure 1).

A model analysis of the variables determining the formation of OSC Definitions of variables are showing in Table 2.

Definition of the determinant variables and their role in the formation of the OSC.

| Variable | Definition | Role in the formation of OSC |

| Relational competence (RC) | An individual quality based on management of interaction techniques that allow to put peers in relation around a target, and build a relational framework suitable to fulfill this objective (Milburn, 2002; Ségal, 2005). | With this variable we want to represent the facet of human personality that favors the formation and maintenance of long-term relationships. In the case of the TBME, this variable determining OSC formation is based on professionalism and technical proficiency of the people involved. Then it is not simply about the ability to make friends. |

| Commitment (CM) | The human condition resulting from the emotional involvement of the employee with respect to the organization in which he works (Simard, Doucet & Bernard, 2005). | An overview of the causes of commitment in a TBME allows to say that the intellectual wealth of workspaces and the nature of the products and services offered are at the origin of the OSC formation opportunities defined by this variable. |

| Working environnement (WE) | Perceptions shared by employees about what is important in an organization, which have been obtained through their work experiences and their perceptions of the expected and maintained types of managerial behavior (Schneider& Bowen, 1995, cited by Yoon, Beatty & Suh, 2001) | The small structure that characterizes the TBME defines a WE that is generally well appreciated by the entrepreneurs, leaders and team members. The very proximity of this organizational size imposes requirements of behavior and attitude, taking into account the existence of a multiplicative effect of individual positions: the discomfort of one person significantly affects the overall WE and generates several problems. |

| Comple-mentarity of roles (CR) | Coordinating the roles in a group (Peplau, 1983). The complementarity of competences involves different experiences and functional tools that can balance each other (Krishnan, Miller & Judge, 1997). | The TBME teams are small but very diverse in terms of the formation of its members. The individual contributions become key, as generally there is only one person per specialty. In such cases, the decision makers are in great need of advice, taking into account the many variables involved in determining the feasibility of a project or specific technological solution. The delegation of responsibilities is also critical. |

| Strategic Orientation (SO) | Although the original concept is much broader and complex, in this research this variable has been chosen to represent the profile of the decisions taken by the managers of the TBME that contribute to the formation of OSC. | To reach an overall orientation towards collective goals, the TBME must, in the first place, define its own SO. This organizational decision federates and gives a meaning to the collective action and at the same time emphasizes the values of the organization. Employees appreciate the perception of a SO from the direction of the organization. This SO provides them with the clarity needed to decide to participate in plans that derive from it. |

| Communication spaces (CS) | The socio-technical system that comprises the different available communication tools in a workspace and social practices of its users. It is composed of oral and written modes of communication, which are used in communication tools: telephone, fax, paper, body. Without being stable, the CS is subject to restructuring by the participants in communication situations (Bailly, 1999). | Even if the life of a TBME is more flexible and informal, these organizations are not exempt from the obligation to define different more formal regular meetings. Because teams are not numerous, everyone can participate in them, and interchange between the less and more experienced are productive to the community. Moreover, TBME quickly adopt computer tools that facilitate their work routines and the emergence of OSC. |

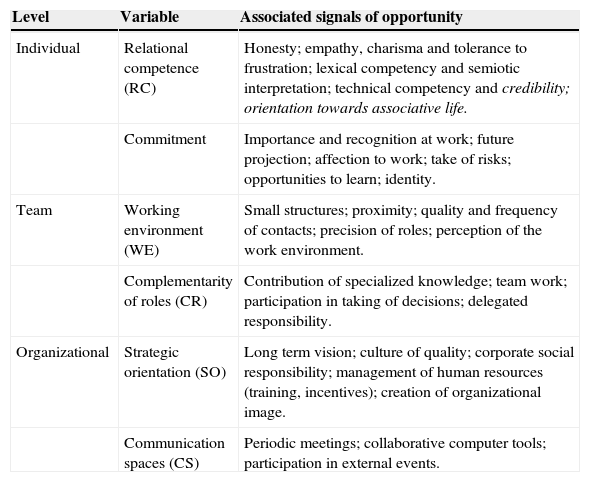

Given the interest of the authors in order to indicate the presence or absence of the determinant variables into a TBME and their positive or negative contribution in the creation of OSC, a set of signals of opportunity was associated with each variable (Table 3). The identification of a signal does not always mean that OSC exists, but it defines an opportunity to form it. Only the convergence of various signals and of all determining variables produces the expected result.

Signals of opportunity associated to the determining variables of OSC.

| Level | Variable | Associated signals of opportunity |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Relational competence (RC) | Honesty; empathy, charisma and tolerance to frustration; lexical competency and semiotic interpretation; technical competency and credibility; orientation towards associative life. |

| Commitment | Importance and recognition at work; future projection; affection to work; take of risks; opportunities to learn; identity. | |

| Team | Working environment (WE) | Small structures; proximity; quality and frequency of contacts; precision of roles; perception of the work environment. |

| Complementarity of roles (CR) | Contribution of specialized knowledge; team work; participation in taking of decisions; delegated responsibility. | |

| Organizational | Strategic orientation (SO) | Long term vision; culture of quality; corporate social responsibility; management of human resources (training, incentives); creation of organizational image. |

| Communication spaces (CS) | Periodic meetings; collaborative computer tools; participation in external events. |

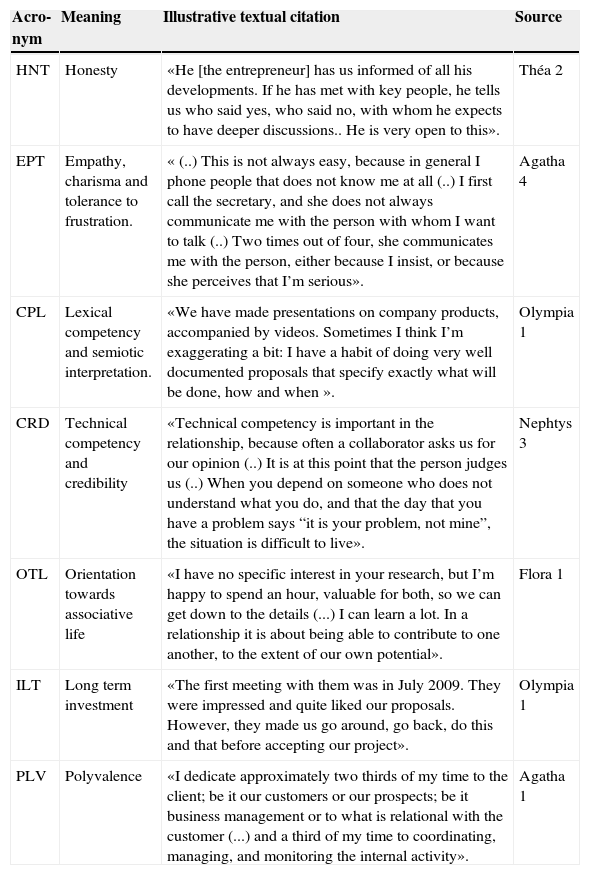

An example of identification of the individual signals associated to one variable is presented below (Table 4). Around the relational competence variable seven signals indicative of the presence of this variable were identified. A verbatim quotation supplements the identification of each signal, and the data source is anonymous for the stage of inter-case analysis.

Signals of opportunity associated to the relational competence.

| Acro-nym | Meaning | Illustrative textual citation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| HNT | Honesty | «He [the entrepreneur] has us informed of all his developments. If he has met with key people, he tells us who said yes, who said no, with whom he expects to have deeper discussions.. He is very open to this». | Théa 2 |

| EPT | Empathy, charisma and tolerance to frustration. | « (..) This is not always easy, because in general I phone people that does not know me at all (..) I first call the secretary, and she does not always communicate me with the person with whom I want to talk (..) Two times out of four, she communicates me with the person, either because I insist, or because she perceives that I’m serious». | Agatha 4 |

| CPL | Lexical competency and semiotic interpretation. | «We have made presentations on company products, accompanied by videos. Sometimes I think I’m exaggerating a bit: I have a habit of doing very well documented proposals that specify exactly what will be done, how and when ». | Olympia 1 |

| CRD | Technical competency and credibility | «Technical competency is important in the relationship, because often a collaborator asks us for our opinion (..) It is at this point that the person judges us (..) When you depend on someone who does not understand what you do, and that the day that you have a problem says “it is your problem, not mine”, the situation is difficult to live». | Nephtys 3 |

| OTL | Orientation towards associative life | «I have no specific interest in your research, but I’m happy to spend an hour, valuable for both, so we can get down to the details (...) I can learn a lot. In a relationship it is about being able to contribute to one another, to the extent of our own potential». | Flora 1 |

| ILT | Long term investment | «The first meeting with them was in July 2009. They were impressed and quite liked our proposals. However, they made us go around, go back, do this and that before accepting our project». | Olympia 1 |

| PLV | Polyvalence | «I dedicate approximately two thirds of my time to the client; be it our customers or our prospects; be it business management or to what is relational with the customer (...) and a third of my time to coordinating, managing, and monitoring the internal activity». | Agatha 1 |

Three proposals synthesize the findings of this research (box 2).

Box 2. Resulting proposals of research.

P1. The OSC is an organizational competency resulting from the action of various key variables provided by actors from three different levels of analysis: the individual level (the members of the organization), a collective level (the teams) and an organizational level (organization, as a decision-making body of the strategy).

P2. Relational competence, commitment, work environment, roles complementarity, strategic orientation and communication spaces are crucial variables for the formation of OSC in a TBME. Relational competence and commitment are crucial individual-level variables; work environment and complementarity are key collectively level variables; guidance and communication spaces are key determinant variables of organizational level.

P3. The identification and monitoring of a set of signals of opportunity facilitate the characterization of the role of each determinant variable in the formation of OSC, and of each constituent relational asset in this competency. The greater the number of identified signals of opportunity, the greater the propensity to form and increase the OSC possessed by a TBME.

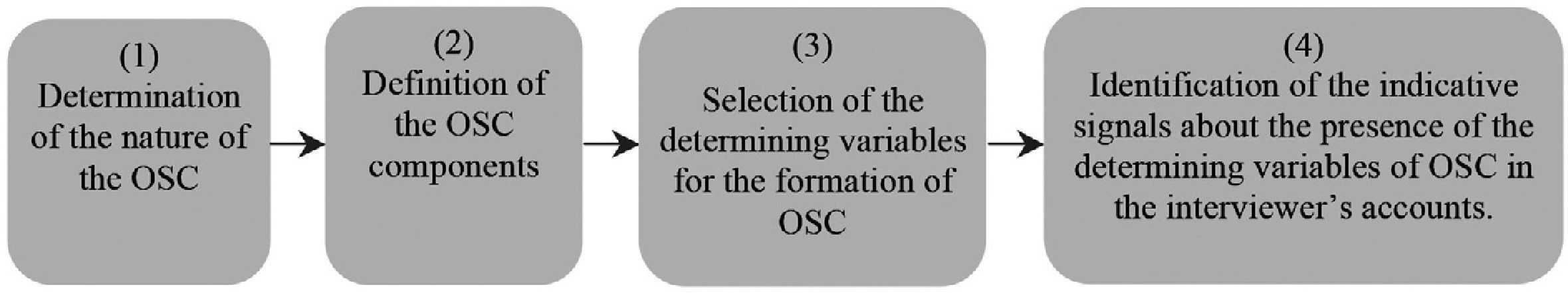

This research will conclude by a returning to the original research question: how to operationalize the concept of OSC to understand it and manage it more effectively?

The operationalization of the OSC is a consequence of the concept that has been attributed to this capital. The reflection of the authors has led to attribute to OSC the quality of organizational competency inseparable of participants in social relations that produce it. Consequently, the next step is to define the components of this capital. In this case, three relational assets were held as OSC components: orientation towards collective goals, mutual trust and shared values. These two decisions determine the fundamentals for the proposed operationalization process.

The details of the subsequent operationalization should respond to the interests of analysts. In this case, the literature review had identified several studies of OSC dealing mainly on the analysis of dyadic relationships constituted by a cause and an effect. A multivariate multilevel analysis then began to take shape over time. After selecting the six key variables from three levels of analysis (individual, team, organization), the authors noted that the identification of these variables determining the formation of OSC in the field was done intuitively. It was then necessary to identify what the signals associated with each variable were in order to perceive its presence in the stories of the interviewees. In short, the problem of operationalizing the OSC was solved by a four-step process (figure 2).

ConclusionsWe proposed a definition of OSC that was inspired by the relevant literature but also features some differences from previous conceptualizations. The differences in our definition start with the assignment of the character of organizational competence to OSC. The organization is oriented to its collective goals, enjoying an atmosphere of mutual trust and shared set of values. Our conclusion is that this company has built a potentiality, i.e., an ability to work together more effectively than other companies, therefore, an organizational competence. This capability may be transversely capitalized in a strategic process generating value: innovation, creation of organizational image, and the transfer and integration of knowledge.

The concept of using relational assets to indicate the components of the OSC became the second distinction of our definition. It was chosen over competing concepts as social resources or simply resources. These last two notions do not target our belief of OSC as we consider them to be too general and could be open to several interpretations. The concept of relational assets, instead, denotes intangible assets that can only spring up within a social relationship, and in our opinion, it is the essence of the OSC.

The timely convenience of research on the OSC is bound to the particular interest of researchers in learning more details about a set of organizations that is distinguished throughout the country. These are small structures that take on the challenge to develop and offer innovative technology solutions to the market, and whose main asset is their own knowledge: technology-based micro enterprises (TBME).

Being a specific population and from the perspective of management sciences, TBMEs have been the object of very few specialized studies, even less regarding the quality of their social relationships. Because the material resources of these organizations are generally limited and their end products tend to be complex, with different or sometimes unique characteristics and with very few competitors, the intuition of the researchers indicated that the knowledge of their backgrounds and their current modus vivendi could become a rich source of insights and analysis on the formation of OSC. We were interested in identifying the variables involved in the formation of OSC in the population of the chosen firms.

We summarized the results of our research in a graphic format. For the formation of OSC, three types of actors must participate: individuals, work teams and organizations. This means that it requires the intervention of an individual and two collective levels of analysis to represent the overlap between them. Our second result was the identification of the signals of opportunity that we associate with the determining variables of the OSC. These signals allow us to anticipate the existence of an appropriate environment to develop OSC.

Six variables were pointed out as determinants of the formation of OSC. We do not claim, with the variables selected in this research, an exhaustive list of those involved in the phenomenon. However, we affirm that the influence of this set of variables is significant. They were chosen because they represent the notions most frequently mentioned by interviewees throughout all our case studies.

The objective of identifying signals of opportunity is the systematization of our preconceptions. Indeed, during the content analysis of the interviews and encountering certain statements of the interviewees, we believe that the variables of interest were present and could contribute to the formation of OSC. It was then necessary to name the signal that aided us in identifying the variable in question, which could be interpreted as an opportunity for the formation of this intangible capital to the extent that its effect could not guarantee a result. Through the reading and researching of the data collection of the same variable, we decided if each variable was a previously identified signal or a different one that was to be identified and added it to the list. We concluded that the list of signals created facilitated monitoring and characterization of key variables of the formation of OSC and of the relational assets that constituted this capital.

Previous research studied dyadic relationships between the variables contained in our analysis model of the formation of OSC. An overview of the said model allows us to conclude that we have identified two types of variables. The first group of variables is highly present in the concerning literature: relational competence (e.g. Baron & Markman, 2000; Hitt & Duane, 2002; Bilhuber, 2009; Omrane et al., 2011), commitment (e.g. Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Leana & Van Buren, 1999; Bolino et al., 2002) and strategic orientation (e.g. Melé, 2003, Pastoriza, Ariño & Ricart, 2009). A second group of variables, against, has a secondary role in the research: work environment (e.g. Huysman & Hulf, 2006) and communication spaces, (e.g. Chen, Chang & Hung, 2008), or it is difficult to discover the complementarity of roles in studies of OSC.

As for the peculiarities of the TBME for the formation of OSC the findings of this research indicate that high market demands, the complexity of the products and services offered, long-term projects that these organizations should undertake daily, the interdisciplinarity and the need of teamwork determine an environment in which the OSC becomes a critical resource.

The multiple case studies gathered by companies belonging to the target population, but also different with respect to particular characteristics, become the evidence that our research proposals are not based on idiosyncratic features of a single organization. Hierarchical leaders and executives of the TBME can benefit from a systemic view of a complex phenomenon as the formation of OSC. The proposed set of signals of opportunity may be subject to a monitoring process designed to control and accelerate the formation of this valuable organizational competency.

Several limitations should be noted with respect to the realized investigation. As for the definition of the research topic, the authors focused on studies of OSC, i.e. the SC possessed by organizations. Consequently some authors, particularly sociologists analyzing the SC of individuals, of communities or countries, were not included in the conducted literature review. There is also no analysis of the effects and features of SC at those levels.

The approach of this research is also focused on non-structural aspects of the formation of OSC. Therefore, the analysis performed does not follow the guidelines of the theory of social networks and the multiple studies analyzing the configuration of these networks also are not part of the focus of this work. Moreover, we have explored the content analysis of OSC. Consequently, neither the effects of the time variable nor the formation of this capital are part of the study.

In regards to the case studies, they were not entirely homogeneous although all organizations belong to the population of interest (TBME). In addition to the differences in features between them, the conduct of these studies did not follow the logic of the theoretical or literal replication characterized by Yin (1994). In contrast, its sequential realization led researchers to make permanent adjustments to better respond to the mature conceptual and to precisions and progressive boundaries of the central subject and the research objectives. The length and variety of sources of each case study were equally affected by favorable or unfavorable situations experienced by the TBME and by the availability and willingness to work of entrepreneurs or senior leadership of organizations.

With regard to the research method, a test of simultaneous analyses of intra organizational OSC (OSCINT) and inter-organizational (OSCEXT) has been carried out, but all the data sources used were internal. In other words, the external stakeholders of the TBSE and TBME studied were not interviewed. Furthermore, content analysis of the interviews was the only technique used for information processing. Some observations of internal documents and inquiries were made as a contrast source and for ratification of interpretations but this analysis was not due to a systematic and documented procedure.

The multilevel analysis realized also has limits. The relationships between the key variables studied are only those between each variable in the analysis model and research leading to construct OSC and the orientation of the analysis is ascending (from the organizational hierarchy lower levels to the upper level) and not in the reverse direction. Thus, the design adopted is only one of many possibilities of multilevel analysis possible in the domain of management sciences.

Other types of organizations have or may have specificities with respect to the formation of OSC that would merit being brought out in future work. It is also possible to elaborate on the cognitive aspects of the formation of OSC, and on their links with the fashionable topic of the cognitive aspects of the strategy.

Deepening on OSC contribution to the creation of organizational value and on the extent of this capital are other possible ways of research. Finally, other architectures of multilevel research can be designed so that it may be possible to analyze other types of relationships among determining variables of the formation of OSC, and the passage from one level to another.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

This term designates intangible relational assets that can only occur in the context of a relationship with the others. These assets are indivisible and cannot be conceived as the sum of the individual assets. On the contrary, they are the product of mutual knowledge, consent and eventually intimacy (Gui, 1996 et 2000).

These authors mobilize the notion of sociability, but with the same meaning given in this work to the “orientation towards collective goals”.

Aerospace, computer, electronics and telecommunications equipment and pharmacy sectors (Hatzichronoglou, 1997).

The new economy is a term that appeared in 1993, it can take at least one of the following meanings (European Commission, 2002): a) the period of sustainable growth in the United States during the 1990s; b) information intensive organizations or knowledge, rather than capital-intensive; c) technology-oriented start-ups; d) the organizations on the NASDAQ; e) organizations that sell their products or services espe- cially online.

At the time of this case study, the company was 5 years old.

www.libreriadelau.com

Quidd = Quantitive Imaging in Drug Development. The 6th December 2012 this company was liquidated in court.

NXP Semiconductors is a global semiconductor company who provide High Performance Mixed Signal and Standard Product solutions that leverage its leading RF, Analog, Power Management, Interface, Security and Digital Processing expertise (www.nxp.com).