The present research aims to study the direct and indirect influence of passion and empowerment on organizational citizenship behavior of teachers in a private university in Thailand mediated by organizational commitment. The sample comprises 124 teachers teaching in the university and the Organizational Citizenship Behavior Scale, adapted by Podsakoff and Mackenzie (1990), Passion Scale, developed by Vallerand, Carbonneau, Fernet and Guay (2008), School Participant Empowerment Scale (SPES) developed by Short and Rinehart (1992) and Organizational Commitment Scale which was modified from the original scale of Meyer and Allen (1991) by Meyer, Allen, and Smith (1993) were employed. The path model with the dependent variable organizational citizenship behavior and the independent variables passion, and empowerment and the mediating variable organizational commitment was tested using regression analysis. There are relationships between passion for teaching, teacher empowerment, and organizational commitment on the organizational citizenship behavior of teachers. The teachers have high level of organizational citizenship behavior, suggesting that they exhibit behaviors of discretionary nature that are not part of their formal role requirements, but which promote the effective functioning of the university.

La presente investigación se propone estudiar la influencia directa e indirecta de la pasión y el empoderamiento en el comportamiento de ciudadanía organizativa de los maestros en una universidad privada de Tailandia mediados por el compromiso organizacional. La muestra comprende a 124 maestros que enseñan en la universidad y se emplearon la Escala de Comportamiento de Ciudadanía Organizativa (Organizational Citizenship Behavior Scale) adaptada por Podsakoff y Mackenzie (1990), la Escala de Pasión (o entusiasmo) (Passion Scale) desarrollada por Vallerand, Carbonneau, Fernet y Guay (2008), la Escala de Empoderamiento de Participantes Escolares (School Participant Empowerment Scale-SPES) desarrollada por Short y Rinehart (1992) y la Escala de Compromiso Organizacional (Organizational Commitment Scale) que fue modificada de la escala original de Allen y Meyer (1991) por Meyer, Allen y Smith (1993). El modelo de trayectoria con la variable dependiente de comportamiento de ciudadanía organizativa y las variables independientes de pasión (entusiasmo) y empoderamiento y la variable de mediación de compromiso organizacional se puso a prueba con el uso del análisis de regresión. Hay relaciones entre la pasión por la enseñanza, empoderamiento del maestro y compromiso organizacional en el comportamiento de ciudadanía organizativa de los maestros. Los maestros tienen un alto nivel de comportamiento de ciudadanía organizativa, sugiriendo que muestran conductas de naturaleza discrecional que no son parte de los requisitos formales de su función, pero que promueven el funcionamiento efectivo de la universidad.

Modernization has changed the infrastructure of universities. There has been adequate emphasis given in technological advancements to create a learning environment for the present generation students. Teachers play a very significant role in the life of the students and the status of the university. The role goes beyond inspiring the students in academics, to make a field for the students to nurture their creativity. As stated by Garg and Rastogi (2006), the success of organizations largely depends on the commitment and effort put by their employees. It is fortunate for an organization when employees commit to an organization by devoting their free time and energy for the growth and prosperity of the organization (DiPaola & Hoy, 2005). Therefore, university lecturers play an important role in the educational system and their proficiency, novelty, and development can lead the organization to success.

In 1983 Smith, Organ, and Near introduced the concept of ‘organizational citizenship behavior’ and they defined it as “discretionary behavior that goes beyond one's official job and is intended to help other people in the organization or to show conscientiousness and support toward the organization” (p. 775). It was stated that organizational citizenship behavior can enhance the efficiency of organizations. Many empirical studies of organizational citizenship behavior were proven to be significant in many service organizations such as restaurants, hospital and hotels. Research indicates a high correlation between organizational citizenship behaviors and efficiency of organization, which means higher organizational citizenship behavior, higher will be the efficiency (Chu, 2005).

There is a scarcity of empirical research on organizational citizenship behavior of higher education in Thailand; therefore, it is interesting to investigate if the predictors of organizational citizenship behavior have a direct impact on the efficiencies of the universities. In the present educational setting the role of the teachers does not confine only to teaching as the university has to keep up to the standards set by the Office of Higher Education Commission. The private universities cannot survive with teachers who are good in teaching alone, the paperwork and the activities involved requires a tremendous effort which extends beyond their traditional role of teaching demands. They also require a more positive attitude and commitment. Chughtai and Zafar (2006) stated the significance of fostering positive organizational commitment among the academic staff, as there is a significant correlation of commitment and citizenship behavior.

Passion is defined as “a strong inclination or desire towards an activity that one likes and finds important and in which one invests time and energy” (Vallerand and Houlfort, 2003). Therefore, passion for teaching can be explained as the inclination or love for teaching or imparting knowledge to their student and invest their time and energy in their work. Another important area of concern that is closely linked to passion is empowerment. According to Wilson and Cooligan (1996), empowered lecturers will be confident in their potential and ability to be able to influence students learning and development. Thus, they have strong individual efficacy expectations. Moreover, it is evident that when the lectures have a sense of control over the job, they exhibit high levels of organizational citizenship. In the same way, when empowered teachers experience meaningfulness in their job, they are more likely to respond with high levels of persistence and motivation, which are likely to translate into high levels of organizational citizenship behaviors (Kirkman & Rosen, 1999; Kirkman, Rosen, Tesluk & Gibson, 2004).

Background of the studyResearch on organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) has received a great deal of attention from researchers with the belief that instructors in the university play a key role in the educational success and the overall efficiency of the university. Instructors with higher organizational citizenship behavior will be willing to spend extra time for the department or for the students and will be voluntarily going out of the way to carry out department or university activities (DiPaola & Neves, 2009). It is very important to study the factors that predict organization citizenship behavior. Though a strong relationship was identified with passion for teaching and citizenship behavior the mediating effect of organizational commitment was not studied to date. Teachers beyond the defined roles, involved in the activities of the department, and quality time with students are good examples of organizational citizenship behavior. It is very important to understand the underlying motivating factors that instigate the teachers to engage in activities which are beyond the requirements of their job roles. The present research aims to study the antecedents of OCB.

Problem statementEmployees’ or lecturers’ committed behavior is critical for an institution's effective functioning.

Several studies on OCB have highlighted the significance of OCB on the success of the organization (Chen, Hui, & Sego, 1998). Researchers believe that the lack of OCB in lecturers can affect the academic performance of students and the success of the organization. It is, therefore, necessary to evaluate the determinants of organizational success in relation to its members’ effort and involvement in organizations. In the university context, it is also necessary to evaluate the determinants of a university's success in relation to the lecturers’ effort and involvement in the organization. Literature review in the area of OCB provides clear evidence that organizational commitment has a positive influence on organizational citizenship behavior (Alotaibi, 2001; Scholl, 1981; Yilmaz & Cokluk-Bokeoglu, 2008). Decision making, which is a sub variable of teacher empowerment also had been identified as a powerful predictor of organizational citizenship behavior (Bogler & Somech, 2004). Lecturers who have a passion for teaching tend to stay committed to the organization (Day, 2004).

Objectives of the study- 1.

To investigate the level of organizational citizenship behavior, passion, empowerment and organizational commitment among teachers in a private university in Thailand.

- 2.

To investigate the direct influence of passion for teaching and teacher empowerment on organizational citizenship behavior of teachers in a private university in Thailand.

- 3.

To investigate the indirect influence of passion for teaching and teacher empowerment on organizational citizenship behavior of teachers a private university in Thailand being mediated by organizational commitment.

It is important to understand the factors influencing OCB of lecturers. Firstly, exploring the concept of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) can add valuable literature on OCB within the university context. Second, this study will enrich the professional lives of the university lecturers by serving as a knowledge resource. Third, the findings, implications, and recommendations of this study will benefit university administrators to create plans and implement action plans to enhance OCB among the university lecturers. For example, if the research findings support that passion for teaching and teacher empowerment significantly influence OCB, then the management can put more emphasis on hiring lecturers who have demonstrated a passion for teaching and give them more freedom or control in their job responsibilities, with an aim to increase their OCBs.

Fourth, if the study variables passion for teaching, teacher empowerment, and organizational commitment are to significantly influence OCB, the study may encourage university administrators to develop and implement training programs and other interventions aimed at enhancing and sustaining the OCBs of teachers under their jurisdiction. Finally, the literature review, findings, and discussions of the study can be useful for further research.

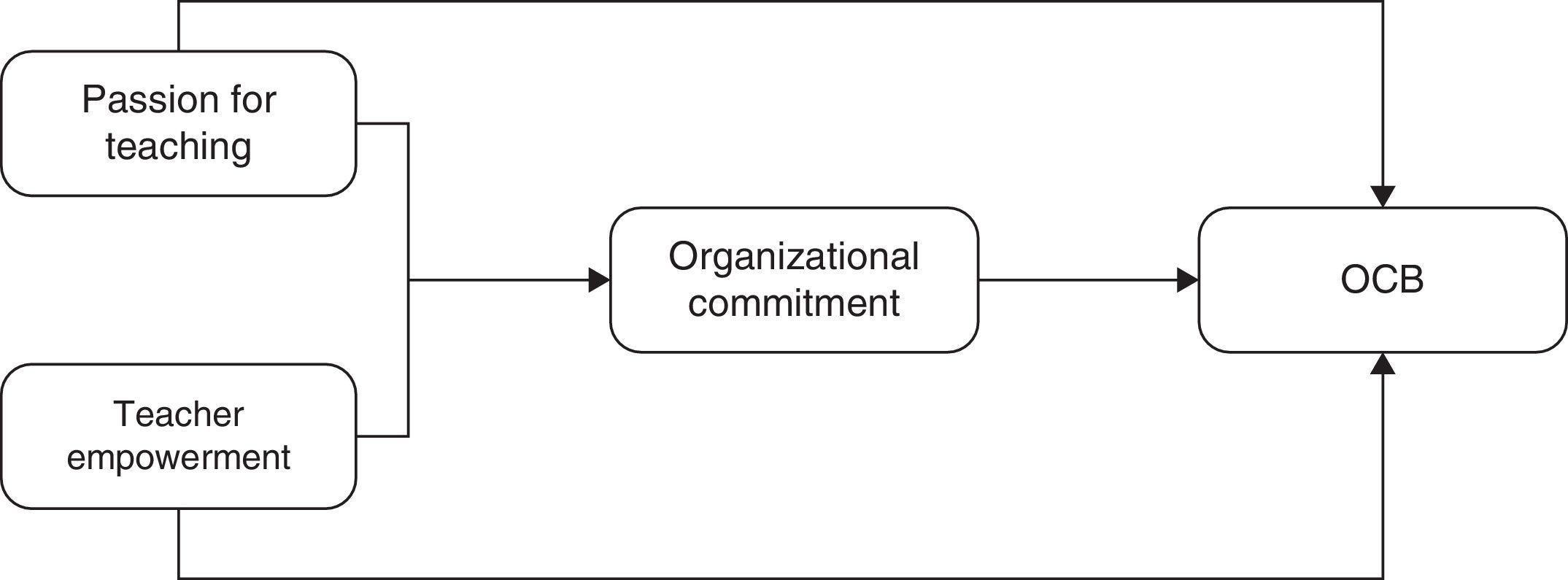

Conceptual frameworkThe study aims to analyze the direct influence of passion for teaching and teacher empowerment on the OCB of the teachers in a private university in Thailand. The investigation also aims to study indirect influence of passion and teacher empowerment on OCB mediated by organizational commitment. The conceptual framework of the current study is proposed, as follows.

MethodResearch hypothesesBased on the path model (Fig. 1) and research question above, the following hypotheses were generated for testing:H1 There is a direct influence of passion for teaching and teacher empowerment on organizational citizenship behavior, such that higher the passion for teaching and teacher empowerment, the higher the organizational citizenship behavior. There is an indirect influence of passion for teaching and teacher empowerment on organizational citizenship behavior mediated by organizational commitment, such that higher the passion for teaching, teacher empowerment, and organizational commitment, the higher the organizational citizenship behavior.

The current study employed a correlational design, via path modeling, to test the research hypotheses. This quantitative study was based on the responses of lecturers in a private university to a survey questionnaire designed to tap the study's primary variables, namely: passion for teaching, teacher empowerment (status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact and autonomy) organizational commitment (affective, continuance and normative) and organizational citizenship behavior.

ParticipantsThe participants of the research are the lecturers of a private university in Thailand. There are 1200 lecturers teaching in the university under different schools/disciplines. The statistical program G*Power 3 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) was employed to determine the required sample size. Setting F-test and the use of multiple regression omnibuses (R2 deviation from Zero), the significance level at .05, power at .95, effect size at .15 (medium) and the number of predictors at 9, the required minimum sample size was determined to be 112. The sample collected was from 123 lecturers from different schools of the university. The convenience sampling technique was employed in obtaining the participants.

Research instrumentationThe researchers used a set of five questionnaires in English – a demographic questionnaire and four self-rating scales. The demographic questionnaire tapped into the demographic variables of gender, age, and years of experience. The first rating scale used was Organizational Citizenship Behavior Scale, adapted by Podsakoff and Mackenzie (1990) from Organ's (1988) version. The original questionnaire with 24 items consisted of five dimensions. The adapted one consisted of 15 items. The five dimensions are: altruism (items 9, 14, 10, 7), conscientiousness (items 11, 13, 15, 2), sportsmanship (items 3, 12, 1), courtesy (items 4, 5), and civic virtue (items 6, 8). Item number 3, 12 and 1 indicates reverse scoring. Podsakoff and Mackenzie (1990) conducted the confirmatory factor analysis of the scale and reported good correspondence with Organ's (1988) theoretical framework. Five factors were identified and all of the items loaded significantly on these factors. The internal consistency reliability of the subscales exceeded .80, except for civic virtue (.70) and good discriminant validity was also reported. Responses to all items were scored on a 7-point Likert Scale ranging from 1=Strongly Disagree to 7=Strongly Agree.

The second part of the survey questionnaire consisted of the Passion Scale, developed by Vallerand, Carbonneau, Fernet, and Guay (2008). This scale was used to measure passion for teaching. The scale consists of two dimensions: the first dimension measures the extent to which people have passion for an activity, and the second dimension of the scale measures harmonious and obsessive passion. The test-retest reliability was done for the scale with retest after 3 months, the Cronbach's alpha reported were .79 and .78 respectively. The Cronbach's alpha for harmonious passion was 0.87 for both times and the Cronbach's alpha of obsessive passion was.76, and. 80 respectively. The scale has 16 items. Items 1, 2, 3, 4 correspond to passion criteria; items 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 14 correspond to harmonious passion; and items 6, 8, 11, 13, 15, 16 correspond to obsessive passion. Responses to all items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale.

The third scale employed was School Participant Empowerment Scale (SPES) developed by Short and Rinehart (1992). The 38-item instrument measures teacher empowerment on six dimensions: decision making, professional growth, status, self-efficacy, autonomy, and impact. The present research employed an adapted version that consisted of 33 items. Items for status are 3, 7, 13, 18, 23, 30; items for professional growth are 2, 12, 17, 27; items for self-efficacy are 4, 8, 14, 19, 24, 28; items for decision-making are 1, 6, 11, 22, 26, 29, 31, 33; items for impact are 5, 10, 16, 21, 25, 32; and items for autonomy are 9, 15, 20. The SPES uses a five-point Likert- type rating scale for each of the 38 items, where 1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neutral, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly Agree. Cronbach's coefficient alpha reliabilities for the subscales measuring the dimensions were reported as follows: .79 for decision-making, .66 for professional growth, .84 for status, .83 for self-efficacy, .83 for autonomy, and .91 for impact. Alpha reliability for the total scale was .94 (Short & Rinehart, 1992, as cited in Klecker & Loadman, 1996).

The fourth survey questionnaire employed was Organizational Commitment Scale which was modified from the original scale of Meyer and Allen (1991) by Meyer, Allen, and Smith (1993).

This is a 24-item scale and responses are made on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1=Strongly Agree to 7=Strongly Disagree. The adapted items which used in this study consisted of 17 Items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 correspond to affective commitment; items 9, 10, 11, 12, correspond to continuance commitment; and items 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 correspond to normative commitment. For items 4, 5, 6, 8, 16 reverse-scoring is used. Meyer and Allen (1991) and Meyer et al. (1993) reported good reliability. Stallworth (2003) reported the reliability of the three commitment scales as high, ranging from .75 to .84. The alpha coefficient for the 24-item organizational commitment scale as a whole is .81.

ResultsThe sample consisted of 123 respondents of whom 49 (39.8%) were males and 74 (60.2%) were females. Their ages ranged from under 20 years to 60 years and above. Of the total sample, 11.4% (n=14) belonged to the age group of 20–29, 35.8% (44) belonged to the age group of 30–39, and 52.8% (65) belonged to the age group of 40 years and above. Of the sample 17.9% (22) had teaching experience of 1–4 years, 26.2% (n=32) had a teaching experience between 5 and 9 years, 16.3% (n=20) had teaching experience between 10 and 14 years, and 39% (n=48) had teaching experience between 15 and 20 years. Majority of the respondents were teachers with 15–20 years teaching experience.

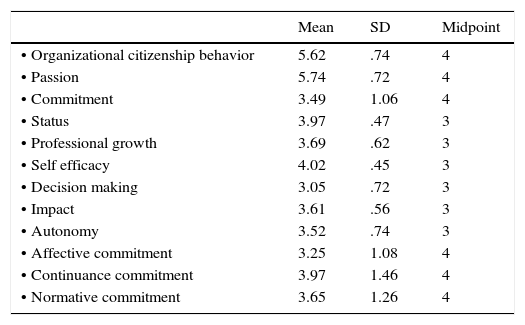

Reliability analysis was conducted for organizational citizenship behavior, passion for teaching, and the subscales of teacher empowerment, and organizational commitment. The purpose of the reliability analysis was to maximize the internal consistency of the measures by identifying those items that are internally consistent (i.e., reliable), and to discard those items that are not. Scale items together with their corrected item-total correlations >0.33 were retained and the factors were computed based on the retained items. The computed Cronbach's alpha coefficients for all 11 scales were above 0.7. After discarding items identified as unreliable (i.e., those with corrected item total correlation <0.33), each of the 11 factors of organizational citizenship behavior, passion, status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact, autonomy, affective commitment, continuous commitment, and normative commitment was then computed by summing across the (internally consistent) items that make up that factor and their means calculated. The following table represents the means and standard deviations for all the computed factors.

It is quite clear from Table 1 that the factors of organizational citizenship behavior, passion, status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact, and autonomy were rated above the midpoint. Thus, overall, respondents rated themselves as having organizational citizenship behavior, passionate in their teaching profession, perceived higher status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact, and autonomy in their teaching realm. While the factors of affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment were rated below the midpoint. Thus, the respondents generally perceived themselves as being less committed to their institution. Meyer et al. (1993) did not give the cut off scores for high and low commitment, hence the scores below the midpoint were considered as low commitment and the scores above midpoint as high commitment.

Means and standard deviations for the computed factors of organizational citizenship behavior, passion, status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact, autonomy, affective commitment, continuous commitment, and normative commitment.

| Mean | SD | Midpoint | |

|---|---|---|---|

| • Organizational citizenship behavior | 5.62 | .74 | 4 |

| • Passion | 5.74 | .72 | 4 |

| • Commitment | 3.49 | 1.06 | 4 |

| • Status | 3.97 | .47 | 3 |

| • Professional growth | 3.69 | .62 | 3 |

| • Self efficacy | 4.02 | .45 | 3 |

| • Decision making | 3.05 | .72 | 3 |

| • Impact | 3.61 | .56 | 3 |

| • Autonomy | 3.52 | .74 | 3 |

| • Affective commitment | 3.25 | 1.08 | 4 |

| • Continuance commitment | 3.97 | 1.46 | 4 |

| • Normative commitment | 3.65 | 1.26 | 4 |

In order to test the hypothesized direct and indirect relationships by the path model depicted in Figure 1, path analysis via regression analysis was conducted. The analysis was done in four steps: (1) a regression analysis was conducted using the factors of passion for teaching, sub variables of empowerment, that are status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact, autonomy, sub variables of commitment that are affective commitment, continuous commitment, and normative commitment as independent variables and organizational citizenship behavior as the dependent variable; (2) a second regression was conducted with the factors passion, status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact, and autonomy as independent variables and affective commitment as the dependent variable; (3) a third regression was conducted with the factors passion, status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact, and autonomy as independent variables with normative commitment as the dependent variable; and (4) a fourth regression was conducted using the factors passion, status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact, and autonomy as independent variables and continuance commitment as the dependent variable.

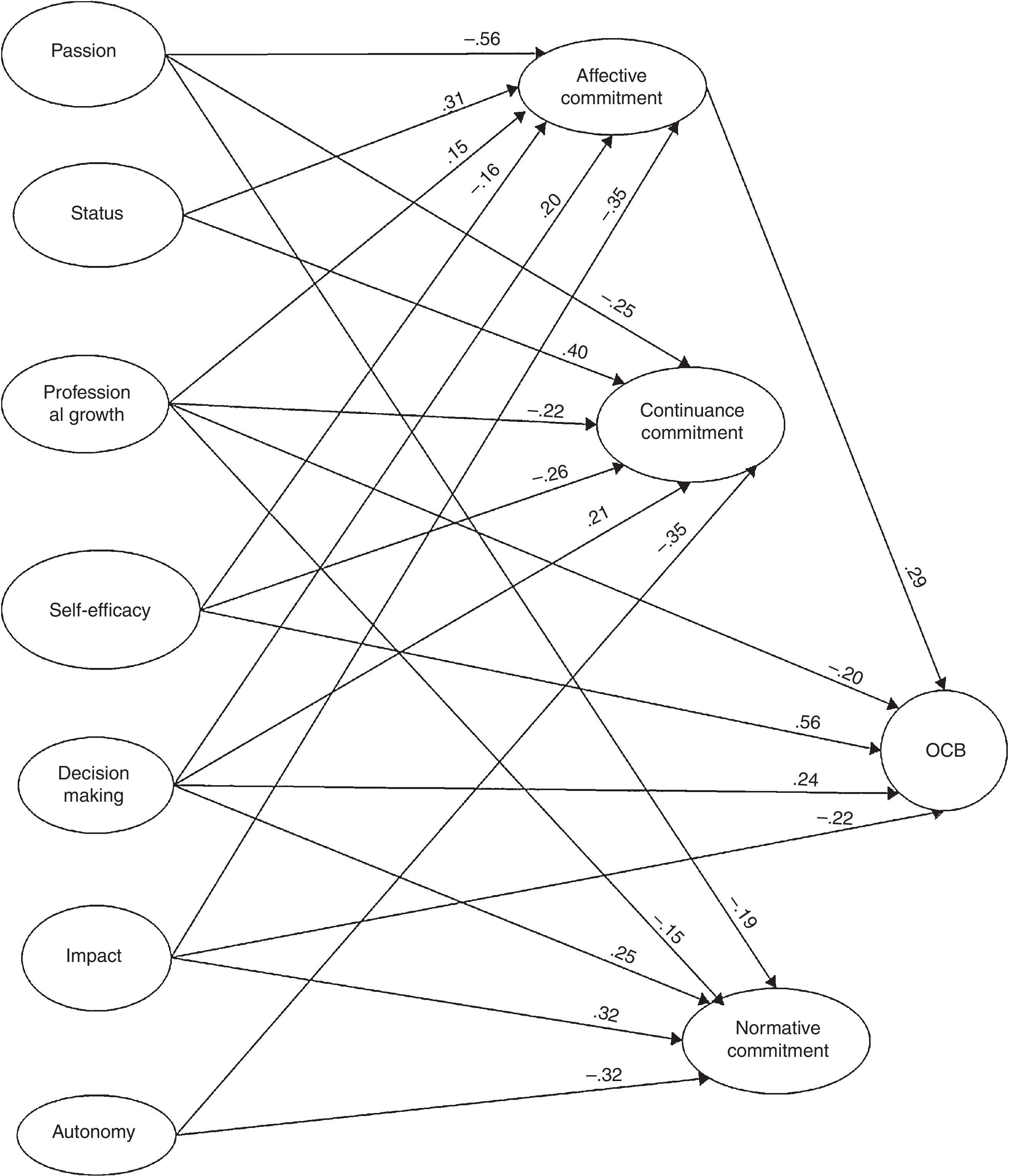

Figure 2 depicts the path model (as a result of path analysis via regression analysis) of organizational citizenship behavior as a function of the direct and indirect influences of their passion and teacher empowerment (status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact and autonomy), being mediated by their organizational commitment (affective commitment, continuous commitment, and normative commitment).

The results showed that professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, and impact have a direct and indirect relationship with organizational citizenship behavior. Thus, the higher the teachers’ perception of professional growth and impact, the lower is their organizational citizenship behavior [(Beta=−.20), t=−3.19, p<.01; (Beta=−.22), t=−2.16, p<.05, respectively)]. The higher the teachers’ perception of decision making power and self-efficacy, the higher is their organizational citizenship behavior [(Beta=.24), t=3.14, p<.01; (Beta=.56), t=6.74, p<.001]. The influence of professional growth, self-efficacy, decision-making, and impact on their reported level of organizational citizenship behavior are also being mediated by their affective commitment. Thus, the higher the teachers’ perceived professional growth and decision making, the higher is their reported level of affective commitment [(Beta=.15), t=2.90, p<.01; (Beta=.20), t=2.95, p<.01]. Subsequently, the higher their affective commitment, the higher is their organizational citizenship behavior [(Beta=.29), t=3.58, p<.001]. The higher the teachers’ perceived self-efficacy and impact, the lower is their reported level of affective commitment [(Beta=−.16), t=−2.17, p<.05; (Beta=−.35), t=−4.24, p<.001]. Subsequently, the lower their affective commitment, the lower is their reported level of organizational citizenship behavior [(Beta=.29), t=3.58, p<.001].

The results also indicated that passion and status have no direct influence on organizational citizenship behavior, but have an indirect influence on organizational citizenship behavior, being mediated by affective commitment. The higher their passion for teaching, the lower is their affective commitment [(Beta=−.56), t=−10.93, p<.001], and the lower their affective commitment, the lower is their organizational citizenship behavior [(Beta=.29), t=3.58, p<.001]. In the case of status, the higher their status, the higher is their affective commitment [(Beta=.31), t=4.31, p<.001], and the higher their affective commitment, the higher is their organizational citizenship behavior [(Beta=.29), t=3.58, p<.001]. It can also be gleaned from the path model that autonomy has no direct or indirect influence on organizational citizenship behavior.

The results also indicated that passion, status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, and autonomy have an influence on continuance commitment. The result showed that the higher the teachers’ passion, professional growth, self-efficacy, and autonomy, the lower their continuance commitment [(Beta=−.25), t=−4.30, p<.001; (Beta=−22), t=−3.82, p<.001; (Beta=−.26), t=−3.18, p<.01; (Beta=−.35), t=−4.57, p<.001, respectively]. Again, the study showed that the higher the teachers’ perceived status, and decision making, the higher their continuance commitment [(Beta=.40), t=4.99, p<.001; (Beta=.21), t=2.83, p<.01 respectively].

The result also showed that passion, professional growth, decision making, impact, and autonomy have an influence on normative commitment. The higher the teachers’ perceived passion, professional growth, and autonomy, the lower their normative commitment [(Beta=−.19), t=−2.86, p<.01; (Beta=−.15), t=−2.37, p<.05; (Beta=−.32), t=−3.68, p<.001, respectively].

Finally, the higher the teachers’ perception that they participate in decision making and have impact on the organization, the higher their normative commitment [(Beta=.25), t=2.88, p<.01; (Beta=.32), t=3.07, p<.01, respectively].

DiscussionThe teachers in this university reportedly go beyond their assigned duties and play extra roles (OCB) for the effective functioning of their respective departments or within the respective subjects they teach. Past research has clearly indicated that empowered teachers tend to exhibit organizational citizenship behaviors (Wall & Rinehart, 1998). The teachers involved in the current study were found to perceive themselves as having high teacher empowerment, indicated by a score above midpoint on all the components of teacher empowerment. This is quite true based on the university structure as the teachers responsible for a subject are given the freedom to design the course according to them and the effectiveness of the course is based on the structure given by the person who handles the course. This can be an explanation why the teachers in this study were found to have high organizational citizenship behavior. This finding is supported by earlier research (Bogler & Somech, 2004) which demonstrated that the more teachers perceived themselves as participating in any of the components of teacher empowerment, the more they exhibit organizational citizenship behaviors in the university.

The teachers in this study were found to be passionate about their work and that they enjoy their teaching. It is evident that the teachers have a strong desire for teaching because they are motivated towards their teaching profession. This is true particularly in Thailand setting as teaching profession is not highly paid compared to other professions or compared to countries. People who come to this profession are the ones who like to teach. This finding is consistent with that of Day (2004) who posited that passion is closely related to motivation. According to Vallerand et al. (2008), one who is intrinsically motivated enjoys the activity in which he engages and, therefore, shares the aspects of liking the activity with the aspect of passion. The teachers under the present research perceived themselves as being empowered (perceived high status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, impact, and autonomy). This may be because the teachers experience and feel that their colleagues respect and appreciate them (status); that they are getting from the university the opportunity to equip themselves personally and professionally (professional growth); they feel that they are capable of helping the students to learn and are equipped with skills so that they perform successfully (self-efficacy); they are involved in decision making relative to curriculum, text books, activities, projects and class schedules, grading, etcetera, and they can see that their decisions actually affect the university's operation (decision making); they feel that they are effective at their job (impact), and they have freedom and control relative to their educational milieu (autonomy). These findings are in line with the findings of Bogler and Somech (2004) who explained that teachers perceive themselves as empowered when the university gives them more responsibility and power of decision making in different areas and this would lead to go beyond their defined roles.

The teachers in this study rated themselves as having low affective commitment, average continuance commitment, and low normative commitment towards the university. This may be true as the employee retention rate of the university seems to be low. The university job requires a lot of extra paper work, as the university follows Thai quality frame work (TQF) for quality control. The teachers might have to fulfill their family responsibilities and they might find it difficult to have a positive attitude towards the tiring and routine paper work and documentation. This can be a reason for their low affective and normative commitment to the university. This finding is supported by a previous study (Karakus & Aslam, 2009) which found that teachers do not have affective, normative, and continuance commitment due to problems with their schools or with their working group. The study also suggested that teachers may have low normative commitment because they assessed their salary as not satisfactory. In addition, as teachers’ external responsibilities and burdens increase, their normative and affective commitment to the profession decreases.

The administrators give them autonomy and they are allowed to participate in decision-making as well as having mutual respect and admiration. Additionally, they may feel that they have an influence on their department/university functioning.

Path analysisPath analysis has resulted in a number of findings relative to interrelationships between and among the key variables. These findings are presented and discussed accordingly in the following section.

First, as a result of path analysis, it was revealed that the respondents’ professional growth, self-efficacy, decision-making, and impact have direct and indirect influence on their organizational citizenship behavior (OCB).

Professional growth and organizational citizenship behaviorThe results indicated that when teachers’ perceived that they have higher professional growth; their reported level of organizational citizenship behavior was lower. This finding is not in agreement with the finding of Bogler and Somech (2004) which demonstrated that teachers exhibit higher OCB when they perceive that they get more opportunities to improve personally and professionally. Usually, teachers have the opportunity to enhance their professional expertise; it is also possible that they might think that it is under utilization of their skills, when they have to participate in activities of university like long hours of proctoring examinations, going through the elaborate rehearsals of graduation ceremony, or other regular activities of university. Finegan (2000) explained that, in order to increase their career marketability, employees seem to take greater responsibility for their own professional growth rather than use it for the success of the organization. Following the same logic, it can be said that teachers might use knowledge expansion, career development or academic research that improves their work profile instead of contributing to the university's development.

Self-efficacy and organizational citizenship behaviorWhen the teachers perceived that they have higher self-efficacy, their OCB was also higher. These findings are in line with that of Bogler and Somech (2004) revealed that when teachers believe they are competent and can adapt with the demands of the students, they would exhibit extra role behavior. University teachers have high belief in their ability to carry out their role effectively in university. Therefore, they perform extra roles beyond the formal ones.

Decision making and organizational citizenship behaviorThe higher the teachers’ participation in decision making, the higher is their reported level of OCB. This is again consistent with the result of Bogler and Somech (2004) who found that decision making is a strong predictor of OCB. Teachers’ participation in joint decision making will most likely lead to their satisfaction with their job and, thus, show more OCB. Teachers’ involvement can increase a sense of fairness and trust among the administrators and management (Koopman & Wierdsma, 1998); this sense of equality increases the willingness of teachers to engage in OCB.

Impact and organizational citizenship behaviorThe higher the teachers’ perception of themselves as having an impact on the school, the lower is their reported OCB. In contrast to the research by Bogler and Somech (2004) that indicated a positive relationship between impact and OCB, the present research found a negative relationship. The result of the current study can be explained that, although the teachers may see that they have the ability and knowledge to influence the life of the students and the university, they may not be necessarily having an emotional inclination towards the management or other aspects of work which would have restricted them from performing organizational citizenship behavior. On the other hand, previous studies have demonstrated that highly committed teachers exhibit high levels of extra role behaviors (Noor, 2009; Stallworth, 2003).

The path analysis also showed that the influence of the teachers’ passion for teaching, status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, and impact on their organizational citizenship behavior is mediated by their affective commitment.

Passion for teaching, affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviorWhen teachers have high passion for teaching, their affective commitment was found to be low; subsequently, when their affective commitment was low, their OCB was also found to be low. This finding is partly supported by Chang (2001) whose study demonstrated that passion for teaching and commitment are positively correlated. This may be because teachers may have a passion for teaching, but if it is out of their control, it can affect the other aspects of their life such as leisure, family, socialization with co-workers, etcetera. Thus, the situation may produce less adaptive outcomes and the teacher may not have any emotional bonding to the university. Vallerand et al. (2008) stated that obsessive passion for teaching comes from controlled internalization and results in negative outcomes. Thus, the lower the affective commitment, the lower is the individual's OCB. Furthermore, when teachers feel less committed to their organization, they may not spend their extra time for the university or institution and may eventually leave, as suggested by Porter, Steers, Mowday, and Boulian (1974) who revealed that workers with low levels of commitment were more likely to leave their institution.

Status, affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviorWhen status of the teachers was higher, their affective commitment is also found higher. Subsequently, the higher their affective commitment, the higher is their OCB. The teachers in this study showed high level of commitment to the school because they perceived that they are given respect and regard by other teachers. In the same vein, Bogler and Somech (2004) found that those teachers who have a high sense of status in their job show high affective commitment, leading to high level of OCB as their contribution to the school. Teachers who feel an emotional attachment to the university or department tend to experience a feeling of ‘ownership’; thus, they would not hesitate to spend their extra time for the success of university. This assertion is supported by previous research (Aube, Rousseau, & Morin, 2007; Gemmiti, 2007) which demonstrated that affective commitment produces extra role behavior.

Professional growth, affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviorWhen the teachers’ experience higher professional growth, higher were their affective commitment; subsequently leading to a higher level of OCB. Teachers in university may identify opportunities given by their school to nurture them personally and professionally and, therefore, may be inclined to give more to the school as evidence of their commitment to the organization and to the enhancement of the profession. In other words, they may feel an emotional bond with university. This argument is supported by Bogler and Somech (2004) who showed that working in a university that encourages professional development may influence teachers’ emotional attachment and commitment to the school and to their job. As a result, the higher the affective commitment, the higher is the individual's OCB.

Self-efficacy, affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviorWhen the teachers experience higher self-efficacy, the lower is their reported level of affective commitment; and the lower the teacher's affective commitment, the lower is their level of OCB. A previous study had shown that there is a positive relationship between self-efficacy and affective commitment (Bogler & Somech, 2004). In contrast, the present study revealed a negative relationship. This may be because teachers in this university may feel quite confident about their teaching skills and may not be committed enough to remain in the organization for a long period of time. Although these teachers may feel confident about their skills and abilities, they may not have intrinsic motivation to have an emotional commitment to the institution, which could be due to several reasons. The internal communication system within the school or department may not be strong enough to create an affective commitment. Thus, it is likely that the lower their affective commitment to the school, the lower is their demonstrated OCB.

Decision making, affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviorThe more the teachers’ participate in decision making, the higher is their affective commitment, which could subsequently lead to a high level of OCB. This position is supported by Bogler and Somech (2004) who found that teachers’ involvement in decision-making resulted in increased commitment to the school, leading to more expression of OCB. When teachers are given the opportunity to participate in decision making that is deemed instrumental to better school performance and more enhanced teaching-learning processes, they are likely to interact more and develop greater emotional and mental attachment to the school; as a result, they may continue to stay in the school. This statement is similar to that of some researchers (Bogler & Somech, 2004; Hoy, Tartar, & Bliss, 1990) who asserted that teachers who feel that they are involved in major decision making may stay longer in the institution and work for the achievement of its goals. It was demonstrated in the present study that the higher the teachers’ affective commitment, the higher is their OCB.

Impact, affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviorThe more the teachers see that they have an impact on school life, the lower their affective commitment, subsequently leading to lower level of OCB. This finding does not concur with that of Bogler and Somech (2004) who found a positive relationship between impact and commitment. In the current study, it may be that the teachers feel that they have influence on university events and student achievement but are not necessarily emotionally attached to the university possibly because of dissatisfaction with complicated working conditions or certain managerial actions. The emotional attachment could also come from the communication system within the school and the co-workers. When they are not attached to the school emotionally their tendency to help out the school in activities will be less. This argument is supported by Karakus and Aslam (2009) who similarly found that the lower the affective commitment, the lower the OCB among organizational members. The path analysis also revealed that passion, status, professional growth, self-efficacy, decision making, and autonomy have an influence on continuance commitment.

Passion for teaching and continuance commitmentWhen the passion for teaching is higher for the teachers, their continuance commitment seem to be lower. A review of literature revealed that some earlier studies explained this outcome by linking type of motivation with job satisfaction and commitment to stay in the organization, suggesting that when employees are intrinsically motivated at work, they exhibit profound enjoyment and satisfaction in the workplace; whereas, when people are extrinsically motivated, they engage in behaviors that might attract some objective outcome or consequence such as concrete rewards or praise (Deci, 1975; Vansteenkiste, Lens, & Deci, 2006). Using the same reasoning, the results of this study may be explained in the case of teachers who are passionate about teaching will not stay for the job benefits. Continuance commitment is associated with the awareness of the costs if they continue to stay in the school or institution vis-à-vis the costs if they leave the school (Karakus & Aslam, 2009).

Status and continuance commitmentThe teachers’ sense of status is more, the continuance commitment seem to be higher. The teachers’ commitment to stay in the same university and department increases because they believe they are respected and praised by their colleagues. Hence, it can be inferred that the teachers in this study might feel that they would lose their status if they leave the university.

Professional growth and continuance commitmentWhen the teachers’ seem to experience higher professional growth, their continuance commitment seems to be lower. The reason may be that the teachers in his study may realize that although they get a lot of opportunities to increase their skill and knowledge for professional advancement, the benefits they receive may be satisfactory enough for them to stay. Thus, they may perceive the benefits associated with continuing in the same job as being unattractive and, therefore, their level of continuance commitment is low.

Self-efficacy and continuance commitmentThe teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs was higher, the their continuance commitment is lower. Bandura (1977) explained self-efficacy based on two dimensions – outcome expectancy and efficacy expectancy. Following Bandura's theoretical perspective, it may be that the university teachers involved in this study perceived that they have competence and skill and that they can make a difference in their students but may not witness a better outcome after teaching. Thus, they may not be satisfied with the outcome they expect from either the students or from the university and hence lower continuance commitment.

Decision making and continuance commitmentThe more the teachers feel that they participate in decision making, the higher is their continuance commitment. In a related study, Smylie (1994) found that participation in the decision making process and the exercise of influence enhances teachers’ commitment to the institution. By the same token, the teachers in this study may perceive that they are involved in decision making, related their course or curriculum and activities, consequently, they feel empowered. This explanation is in complete agreement with that of Bogler and Somech (2004).

Autonomy and continuance commitmentWhen teachers’ experience higher sense of autonomy, their continuance commitment is lower. The teachers who participated in this study may perceive themselves as having a high sense of freedom and control over aspects of their work such as curriculum development, scheduling, textbook and instructional planning but are not necessarily committed to the institution. Freedom in the work may not actually satisfy them to stay with the university. There may be other motivators that are not satisfied, for them to stay with the university. The path analysis also studied that passion, professional growth, decision making, impact, and autonomy have an influence on normative commitment.

Passion for teaching and normative commitmentWhen the teachers have more passion for teaching, their normative commitment is low. Though they teach well and have a strong internal inclination towards their profession, they may not feel committed to continue their job with the university, if they have better options. It can be inferred from the findings that many teachers may feel little or no obligation to continue working with this university as they don’t have any kind of contracts signed or other external pressures to continue with the job.

Professional growth and normative commitmentWhen teachers’ perception of professional growth is more, their normative commitment is less. Usually, when university provides more opportunities for teachers to improve their professional skills and abilities, they are expected to work harder and perform better in order to improve their university's performance and effectiveness. When university provides opportunity for professional advancement like training and workshops to enhance their skills, they take it up. Though they are happy about their professional growth, they are not obliged to have a commitment to continue their job in the university, if they have better options. Research and external professional service like working as a consultant to other business organizations are considered as activities that enhance their professional growth. Though these activities enhance the image of the university, they may not necessarily be a motivator to stay committed to the university. If there are better opportunities available, they would not mind quitting the job, even though they have opportunities for professional growth.

Decision making and normative commitmentThe more the teachers feel they are involved in decision making, the higher is their normative commitment. It can be inferred from this finding that teachers feel empowered when they participate in critical decision making that affects their work and school functioning. The teachers may feel there is a fair redistribution of power and authority within the organizational hierarchy, as suggested by Lambert (1999). These feelings and insights are likely to translate into feelings of obligation to remain with the organization. It would be easy to assume that teachers who believe that they are empowered through participation in decision making will not leave the university because of a moral sense of duty, or that they feel the need to stay in the university because it an obligation, as suggested by Yavuz (2010). Dulyarkorn (2010) likewise found that decision making increases normative commitment.

Impact and normative commitmentThe higher the teachers perceive they have impact on their school events and life, the higher is their normative commitment. Logically, when teachers feel that they have an influence on what is going on in the school, they feel empowered and are likely to be contented and satisfied in their job. They feel a psychological contract with the university and its administrators, thus developing normative commitment to the institution (Roussenau, 1995). In the same vein, Yilmaz and Cokluk-Bokeoglu (2008) found that career satisfaction is a predictor of normative commitment.

Autonomy and normative commitmentThe higher the sense of autonomy teachers’ experience, higher is their normative commitment. This finding is not in agreement with the finding of Bogler and Somech (2004) who demonstrated that there is a positive relationship between autonomy and commitment. Earlier, Harvey, Barnes, Sperry, and Harris (1974) found that individuals with internal locus of control think that they are capable of exercising control over their achievements and failures, and that they are likely to attribute the thoughtfulness and retributions they get to their own actions rather than to the kindness and generosity of their boss. In the same light, if the teachers in this study believe they have freedom to make decisions related to school aspects such as selection of books, adjusting the courses, activities, introducing plans for curriculum development, but these situations can be interpreted as proof of their personal competence and ability to control various aspects of their working life rather than an act of kindness or a favor granted by the management. Teachers’ perceptions taken in this context may dampen their feelings of obligation and gratitude to the school, as suggested by Harris (2005).

Limitations of the studyIt is essential to note the limitations of this study. First, the study's findings are only be generalized to the teachers in a private university in Thailand. In addition, the present study's variables may not be culturally relevant in the East since the theories underlying the primary variables of the study were developed and applied mainly in the West. For example, the Western educational system and the university culture are different from the Eastern educational system. Further to this, the same argument applies to the research instrumentation used in the present study. The instruments were developed and used in the western setting. Thus, the above drawbacks and limitations could have contributed to some of the inconsistencies between the findings of the current study and those of studies cited in-text.

ConclusionsOn the whole, it can be concluded that there are relationships between passion for teaching, teacher empowerment, and organizational commitment on the organizational citizenship behavior of teachers in a private university in Thailand. Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Bommer (1996) reported that leadership style can influence organizational citizenship acts. Administrator's leadership style plays an important role. Later on, Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Paine, and Bacharach (2000) empirically found that leadership and characteristics of work environment affect organizational citizenship behavior more than worker's personality. The teachers who participated in this study have a high level of organizational citizenship behavior, suggesting that they exhibit behaviors of discretionary nature that are not part of their formal role requirements, but which promote the effective functioning of university. In addition, these teachers have a high sense of passion for teaching, suggesting that they have generally strong inclination or desire towards their profession, which they find important, and worth investing their time and energy. It can also be concluded that the teachers under study have a high level of teacher empowerment, suggesting that they believe that they have developed the competence to take charge of their own personal and professional growth and resolve their problems as well as those of the university. Teaching job in Thai university has more autonomy and teachers have the freedom to do research or do consultation services outside the university and can enhance their professional expertise. The research or consultation services are done independently. It is a challenge for the administrators to align their personal goals in line with the university goals. Though the personal development also contributes to the university goal, this may not enhance their commitment to the university. Finally, this researcher concludes that, in spite of all the given positive aspects of their work, teachers in this university have low commitment to the university. In effect, the psychological state that binds the teachers to their respective university is weak, suggesting that their emotional attachment and faithfulness to the university is fragile and may be compromised if certain intrinsic needs are not met.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.