Spindle cell oncocytoma (SCO) is a low-grade neoplasm in the sellar region originally described by Roncaroli y cols.1 in 2002. SCO is a rare tumor that accounts for 0.1% to 0.4% of sellar tumors, with a mean age at diagnosis of approximately 60 years and no sex differences.2–4 The fourth edition of the World Health Organization classification of endocrine tumors (EN-WHO2017)2 includes SCO as a non-neuroendocrine tumor of the pituitary gland within a rare group of tumors, defined by positive immunohistochemical staining for thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), which also includes pituicytoma, glandular cell tumor, and sellar ependymoma. The relevance of distinguishing between these tumor subtypes is currently questioned, because they show histological heterogeneity and characteristics that frequently overlap.2 Constitutive TTF-1 expression in these tumors points toward a common pituitary origin, ruling out the initial hypothesis that SCO originated from folliculostellate cells, which are negative for TTF-1.2,3 SCO is now considered to originate from proliferation of oncocytic pituicytes in the adenohypophysis,2 although its origin in pluripotent cells has been suggested.4,5 To date, less than 40 cases of pituitary SCO have been reported in the literature.3 Despite its nature of non-endocrine tumors, at least three cases of SCO with clinical signs of hormonal overproduction by the tumor have been reported.6–8 A patient with Cushing’s disease caused by an adenohypophyseal oncocytoma is reported here.

This was a 69 year-old woman with no toxic habits, a pathological history of hypertension with mild hypertensive heart disease treated with three antihypertensive drugs, and osteoporosis with no previous pathological fractures. In August 2017, the patient was referred to the department of endocrinology and nutrition for screening for Cushing’s syndrome due to significant weight gain, with worsening of blood pressure control and osteoporosis. Use of exogenous corticosteroids was excluded. Physical examination revealed body fat redistribution with central obesity and loss of muscle mass in the limbs, proximal muscle weakness, moon face and buffalo hump, and hirsutism. Body mass index (BMI) was 30.9 kg/m2. She had a thin skin but no purple striae. Basic biochemistry tests revealed moderate hypernatremia (Na 148–151 mmol/l) with hypokalemia (K 3.25 mmol/l) and metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.48; HCO3― 31 mmol/l) as significant findings. Hormone evaluation showed elevated cortisol levels in 24 h urine of 253 μg/24 h (normal range, 12.8–82.5 μg/24 h), elevation of basal cortisol levels at 8 h to 25.8 μg/dl (normal range, 4.3–22.4 μg/dl), and two elevated nocturnal salivary cortisol measurements (at 23 h) of 7.87 and 13.93 ng/ml respectively (normal range <1.00 ng/ml). In this context of hypercortisolism, an ACTH level of 31 pg/ml (normal range 5−46 pg/ml) was found, confirming the diagnosis of ACTH-dependent hypercortisolism. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a 5 mm nodular image in the right posterior area of the adenohypophysis. Catheterization of inferior petrosal sinuses with CRH stimulation showed lateralization to the right of ACTH secretion, which confirmed the pituitary origin of Cushing’s syndrome (ACTH in peripheral vein: 7 pg/ml at 0 min, 22 pg/ml at 3 min, 27 pg/ml at 5 min, 24 pg/ml at 10 min; ACTH in right petrosal sinus: 23 pg/ml at 0 min, 509 pg/ml at 3 min, 529 pg/ml at 5 min, 285 pg/ml at 10 min; ACTH in left petrosal sinus: 9 pg/ml at 0 min, 458 pg/ml at 3 min, 295 pg/ml at 5 min, 128 pg/ml at 10 min). The pituitary tumor was resected using the transsphenoidal approach with no incidents. The pathological study (Fig. 1) found oncocytic changes which were confirmed by electron microscopy. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for ACTH and GH, but not for FSH, LH, TSH, or prolactin. One year after surgical resection of the tumor, the patient had central adrenal insufficiency (ACTH 6 pg/ml, cortisol 0.9 μg/dl) that was treated with hydrocortisone at replacement doses. There were no deficiencies in all other pituitary hormones. The patient had a good clinical course, with a weight loss of 68.7 kg to 64 kg, and improved blood pressure control. One of the three antihypertensive drugs could be discontinued. Magnetic resonance imaging one year after surgery showed no evidence of pituitary lesions, and postoperative changes in the sphenoid sinus were only reported.

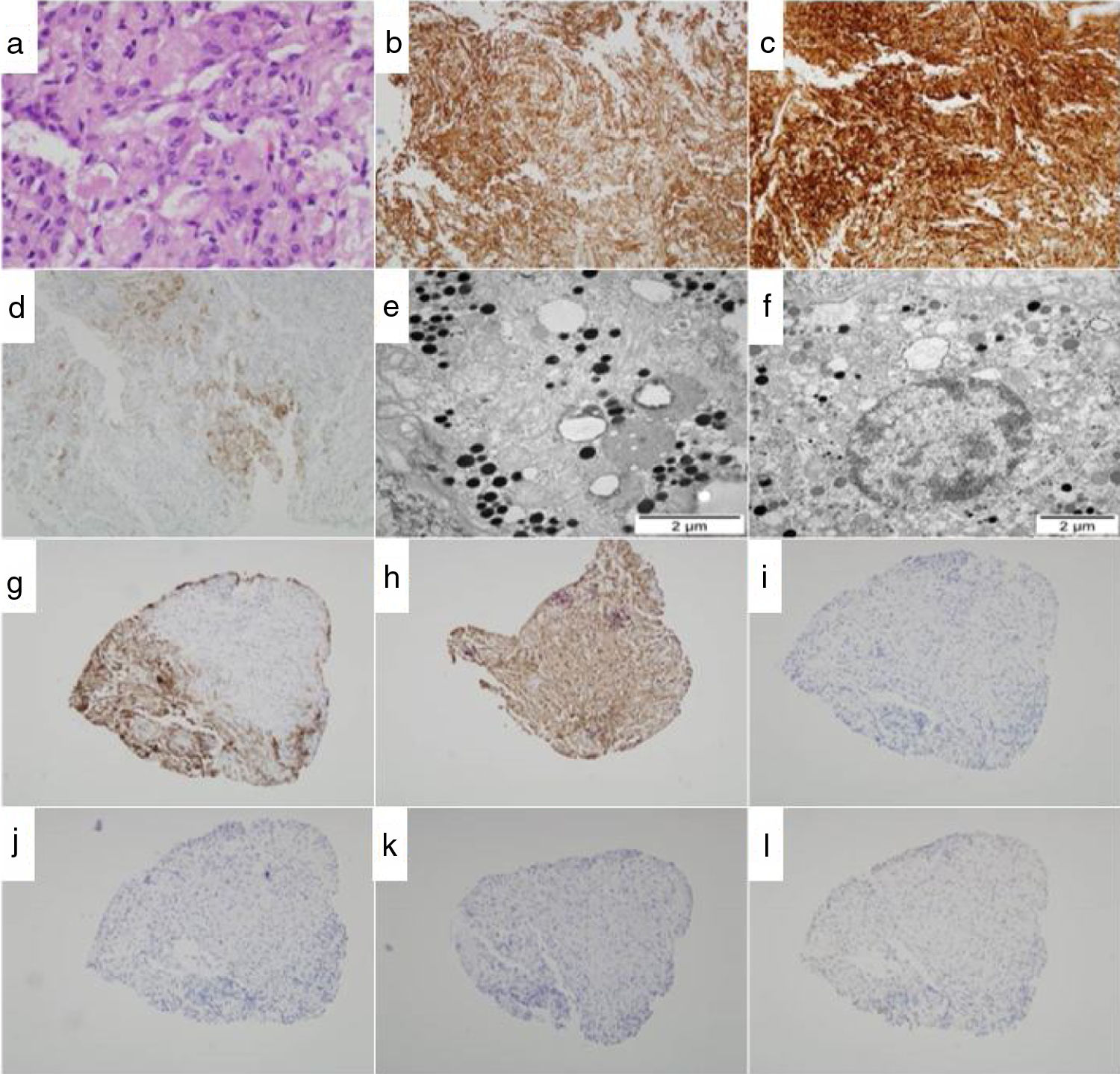

Histopathological and immunohistochemical study of the pituitary tumor (consecutive sections). (a) Microstructure of SCO based on cells with oncocytic changes with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (HE, ×29). (b–d) Immunohistochemical stains: b, vimentin; c, protein S-100; d, EMA (×10). Immunohistochemistry was negative for CD34, glial protein, desmin, and C-kit (not shown). (e–f) Ultrastructural study by electron microscopy. Oncocytic cells with abundant secretory granules and mitochondria are seen. Magnification: ×10,500 (f), ×13,500 (e). (g–l) Immunoprofile: g, ACTH; h, GH; i, FSH; j, LH; k, TSH; l, prolactin (×2.5).

Despite its definition as non-neuroendocrine tumors, at least three more cases of SCO associated with hormone overproduction have been reported in the literature. One case of SCO diagnosed by electron microscopy was reported in a 19 year-old woman with hyperprolactinemia, GH deficiency, and clinical signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism that relapsed after surgery as Cushing’s disease.6 Hormone immunohistochemical analysis of the surgical specimen was not available in this case. An SCO was subsequently reported in a 24 year-old woman with clinical signs of amenorrhea and galactorrhea attributed to prolactin secretion by the tumor, with positive staining for prolactin in the histopathological study.7 More recently, a 19 year-old woman was reported to have Cushing’s disease due to ACTH overproduction by an SCO, also confirmed by an immunohistochemical study.8 It should be noted that the first two cases cited were published in 1978 and 1980 respectively, and the diagnostic and therapeutic approach, as well as the pathological assessment techniques, are therefore not comparable to current techniques. In the case reported here, immunohistochemical staining for TTF-1 could not be performed either due to a lack of archived tumor tissue. In addition, the potential coexistence of an ACTH-secreting pituitary microtumor that had not been diagnosed in the pathological analysis cannot be ruled out in any of the cases.

Hormone overproduction in some of the cases of adenohypophyseal SCO supports the hypothesis pointing to its origin in pluripotent cells able to acquire a mesenchymal or neurosecretory phenotype during the differentiation process,5 with the possibility that oncocytes acquire the ability to synthesize hormones. The importance of reporting all cases of SCO with hormone overproduction and the need for targeted studies on the cellular origin of SCOs, as yet unknown, is therefore demonstrated.

Please cite this article as: Ballesta S, Chillarón JJ, Alameda F, Lafuente J, Carrera MJ. Enfermedad de Cushing debida a un oncocitoma hipofisario: reporte de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:208–210.