Mauriac syndrome is a rare clinical condition predominantly observed in patients with poor glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes.1 Classically, this syndrome is characterised by short stature, delayed puberty, hepatomegaly, cushingoid features, muscle weakness, elevated serum transaminases, and hypertriglyceridaemia. Persistent hyperlactataemia, however, is not a well-recognised feature of the clinical spectrum.2 Herein, we present two cases of young patients with type 1 diabetes who arrived at the emergency department with hyperglycaemia, hepatomegaly, and persistent lactic acidosis.

An 18-year-old woman presented at the emergency department with a history of severe and diffuse abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. She had type 1 diabetes mellitus diagnosed 9 years earlier and was treated with a premixed insulin regimen. She also reported to have primary amenorrhoea, and hypertriglyceridaemia treated with bezafibrate. Importantly, in the past year she reported two previous hospitalisations due to hypertriglyceridaemia-induced pancreatitis and diabetic ketoacidosis. The patient had Cushing sign, dorsocervical fat pad, and non-tender hepatomegaly. Laboratory tests reported a random glucose level of 392mg/dl and an HbA1c of 11.7%. Urinalysis revealed ketonuria, blood ketones resulted in positive, and the venous blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.00, bicarbonate of 3.0meq/dl, an anion gap of 18, and lactate of 6.3mmol/l; which confirmed the diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis. Additional laboratory data revealed a mild elevation of alkaline phosphatase, amylase level of 575U/l, and triglyceride levels of 535mg/dl. Serum transaminase levels and other tests were within normal ranges. An abdominal CT scan was performed to evaluate her abdominal pain and hepatomegaly (24cm) and an enlarged pancreas without peripancreatic inflammatory changes compatible with Balthazar B pancreatitis were found. Serological test for hepatitis B, C, HIV, and anti-nuclear antibodies resulted in negative. The patient was treated with fasting, IV insulin and Ringer's lactate solution. Both diabetic ketoacidosis and acute pancreatitis were resolved without complications 48h later; however, hyperlactataemia persisted with an average level of 4.5mmol/l without objective signs of hypoperfusion during her hospital stay. The clinical diagnosis of Mauriac syndrome was made, and our patient was discharged with normal serum lactate levels.

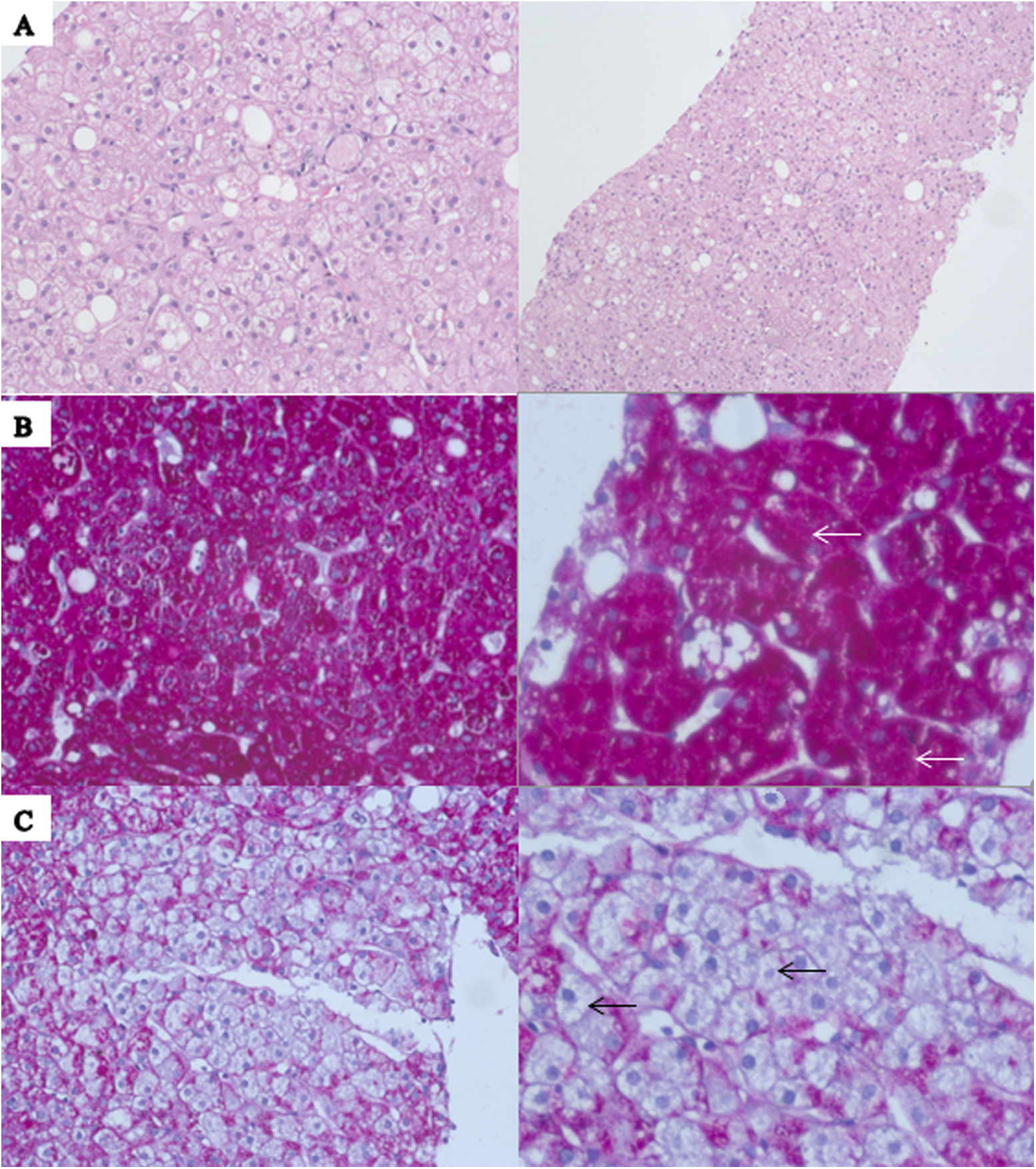

A 24-year-old woman with a history of type 1 diabetes diagnosed 16 years earlier, treated with intermediate-acting insulin because of a low-income household level, presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that started one week before her arrival. She reported several hospitalisations due to acute hyperglycaemic crises in the past years. Her physical examination was relevant for tachycardia, tachypnoea and hepatomegaly. A serum glucose of 512mg/dl, and HbA1c of 11.9% were reported. Urinalysis revealed ketonuria, blood ketones resulted in positive, and the blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.01, bicarbonate of 3.0meq/dl, anion gap of 20, and lactate of 3.3mmol/l; with the previous information, the diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis was made. Additional laboratory data revealed aspartate aminotransferase of 149U/l, alanine aminotransferase of 200U/l, and normal total bilirubin. Serological test for hepatitis B, C, HIV, and anti-nuclear antibodies resulted in negative. Diabetic ketoacidosis was treated according to American Diabetes Association guidelines3 and resolved after 24h. However, hyperlactataemia persisted until day six with an average level of 6.7mmol/l without objective signs of hypoperfusion during her hospitalisation. A liver biopsy was performed to establish a definitive diagnosis. Histopathological results reported accentuated cell membranes, glycogenation of the nuclei, and the presence of abundant glycogen on the hepatocytes, confirming the diagnosis of glycogenic hepatopathy (Fig. 1 A–C). She was discharged with normal transaminases and normal serum lactate levels.

(A) Haematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrates preserved parenchyma architecture with typical hepatocytes diffusely swollen with rarefaction of the cytoplasm, accentuated cell membranes and glycogenation of the nuclei; it may be accompanied with large fatty droplets on liver tissue. (B) Periodic acid-Schiff staining is positive for the presence of glycogen (white arrows). (C) Confirmed after diastase digestion causing the presence of pure glycogen within the hepatocytes (black arrows).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of Mauriac syndrome with both diabetic ketoacidosis and hypertriglyceridaemia-induced pancreatitis. Both cases emphasise the existence of these reversible metabolic abnormalities in patients with type 1 diabetes and the importance of adequate glycaemic control.

Glycogenic hepatopathy is developed due to prolonged periods of hyperglycaemia in which glucose enters the hepatocytes through GLUT2 transporters.4 Then, glucokinase converts the glucose into glucose-6-phosphate with subsequent trapping in the liver cells.4 The presence of insulin in greater concentrations promotes glucose-6-phosphate to glycogen polymerisation, with glycogen accumulation in the liver.5 Those mechanisms lead to hepatomegaly and elevated serum transaminase levels, which vary significantly from normal to 10 times the upper reference limit.6 High levels of transaminases and a hyperdense liver on CT are congruent with glycogen hepatopathy found in Mauriac syndrome.7 Even though transaminases in the first case were within normal ranges, this is not a limit to make the diagnosis of Mauriac syndrome. Transient elevation of transaminases is also a common laboratory feature in DKA, reported in approximately 40% of the cases.8 Further investigation should be made if transaminases fail to rapidly normalise on their own or hepatomegaly persists without improvement.8

Although cushingoid features are presumed infrequent at present, moon face and a dorsocervical fat were found on examination of our patient. Physicians should avoid ordering laboratory tests looking for the diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome since the cause of cushingoid features is presumably due to a physiologic hypercortisolism secondary to poorly controlled diabetes and those tend to resolve after a better glycaemic control is reached.

Mauriac syndrome must come to the physician's mind when hepatomegaly appears in a patient with uncontrolled type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diagnosis becomes more probable when hepatomegaly is accompanied by delayed puberty, cushingoid features, and growth retardation.

Histopathological assessment may be essential for a definitive diagnosis for glycogenic hepatopathy in Mauriac syndrome; however, if the clinical presentation is consistent enough like occurs in our first case, it could be diagnosed conservatively.9

Both cases represented a diagnostic challenge in the emergency department since they presented as a hyperglycaemic crisis, making it easy to omit the diagnosis of Mauriac syndrome. These cases also emphasise the clinical relevance of persistent hyperlactataemia during their treatment since it is recognised as a marker of hypoperfusion. However, hyperlactataemia must be correlated with the clinical condition of every patient to avoid overtreatment. Our patients were normotensive and asymptomatic; therefore, we classified their persistent hyperlactataemia as a part of the spectrum of Mauriac syndrome.

It is important to recall that in the spectrum of abnormalities that can exist in a patient with Mauriac syndrome, persistent hyperlactataemia with a normal pH may be present for several days even after the resolution of a hyperglycaemic crisis.

Mauriac syndrome's varying clinical presentations represent a diagnostic challenge for physicians; these case series highlight the need to actively search for laboratory and clinical findings such as puberty delay, cushingoid features, growth retardation, hepatomegaly, and persistent hyperlactataemia when encountering type 1 diabetes patients.

Source of fundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose. All co-authors agree with the manuscript and certify that the submission is original work and is not under review at any other publication.