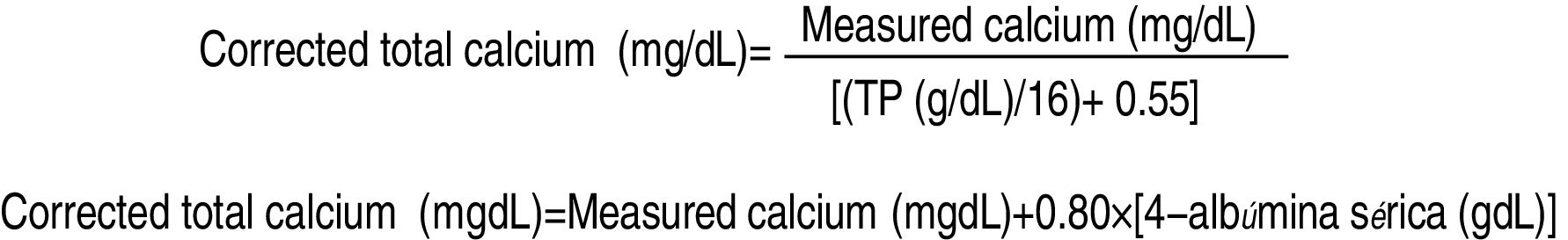

Plasma calcium is the parameter most commonly used to determine patient calcium levels in clinical practice. However, in certain physiological conditions, plasma calcium may not reflect the true clinical situation of the patient. Calcemia (blood calcium concentration) is closely regulated in the body, with total calcium values between 2.2 and 2.6mmol/l (9–10.5mg/dl) and ionic calcium values between 1.1 and 1.4mmol/l (4.5–5.6mg/dl). Forty percent of circulating plasma calcium is bound to proteins (mainly albumin, but also to globulins), 6% is bound to phosphates, citrate and bicarbonate, and the remaining 54% corresponds to ionic calcium.1 The total calcium values change when the plasma protein levels change, while ionic calcium remains unchanged.2,3 Situations where calcemia can be strongly influenced by changes in plasma protein levels include volume overload, malnutrition and nephrotic syndrome. Hypoalbuminemia can also be found in patients with cancer or surgical complications (bleeding, fistula, intestinal perforation, etc.). In these cases, we observe a decrease in total plasma calcium, but not in ionic calcium, a situation known as pseudohypocalcemia.4 There are other circumstances in which total calcium is hardly evaluable, such as a reduced glomerular filtration rate and alkalosis, since alterations in acid-base equilibrium cause H+ ions to compete with Ca2+ for the protein binding points, though total calcium remains unchanged.5–7 However, when there are alterations in acid-base equilibrium, the free calcium fraction is modified, and the patients clinically manifest hypocalcemia due to a decrease in ionic calcium, thereby underlining the importance of determining it through laboratory tests.8 Of note is the high frequency of hypoproteinemia in patients subjected to total parenteral nutrition (TPN) (approximately 85%9), which points to the need for strict control in such cases. When interpreting the biochemical parameters of a patient, uncorrected plasma calcium is of no diagnostic value and must be confirmed by the measurement of ionic calcium as the gold standard. When ionic calcium cannot be determined, the total protein (TP) or albumin correction methods can be used (Fig. 1).1,5

A series of cases are presented below, corresponding to patients receiving TPN and followed-up on by the Nutrition Unit of Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal (Madrid, Spain). An analysis is made of the best calcium adjustment method for the diagnosis of hypocalcemia, using equations that correct the plasma calcium levels and afford estimates that are closer to the real concentration.

The indications of TPN were as follows: case 1: a 53-year-old woman operated upon due to a pelvic tumour; case 2: a 54-year-old male with perforation of the sigmoid colon and peritonitis; case 3: a 60-year-old woman with peritoneal pseudomyxoma and peritoneal carcinomatosis; case 4: a 72-year-old male with urothelial carcinoma, chronic calcifying pancreatitis and acute lithiasic cholecystitis; case 5: a 79-year-old woman operated upon due to postsurgery eventration; case 6: a 56-year-old male with esophageal adenocarcinoma; and case 7: a 74-year-old male with a metal mitral valve prosthesis and annuloplasty, pneumonia and respiratory distress syndrome.

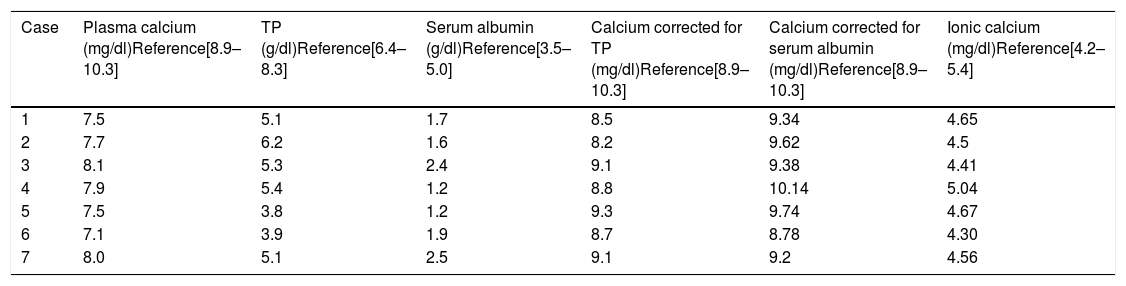

Total plasma calcium, TP and albumin were analysed with the ARCHITECT c16000 Abbot system (the routine protocol in the laboratory of our hospital), and TP and albumin correction methods were used. Ionic calcium was determined by potentiometry (GEM Premier 4000 gasometer). In order for hypocalcemia to be symptomatic (Trousseau and Chvostek signs), calcium levels must be <8mg/dl. The above-mentioned patients had low calcium levels without clinical manifestations, no history of hypocalcemia, and were not receiving drugs capable of inducing hypocalcemia. With correction, plasma calcium was seen to exceed 8mg/dl. Fifty-seven percent of the patients continued to show hypocalcemia after calcium correction for proteins, but only 14% showed hypocalcemia after correction for albumin. On contrasting these values with those of ionic calcium, all the calcium values were found to be normal (pseudohypocalcemia) (Table 1).

Plasma calcium levels, total protein levels, serum albumin levels, corrections and ionic calcium corresponding to each of the patients analysed.

| Case | Plasma calcium (mg/dl)Reference[8.9–10.3] | TP (g/dl)Reference[6.4–8.3] | Serum albumin (g/dl)Reference[3.5–5.0] | Calcium corrected for TP (mg/dl)Reference[8.9–10.3] | Calcium corrected for serum albumin (mg/dl)Reference[8.9–10.3] | Ionic calcium (mg/dl)Reference[4.2–5.4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 8.5 | 9.34 | 4.65 |

| 2 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 1.6 | 8.2 | 9.62 | 4.5 |

| 3 | 8.1 | 5.3 | 2.4 | 9.1 | 9.38 | 4.41 |

| 4 | 7.9 | 5.4 | 1.2 | 8.8 | 10.14 | 5.04 |

| 5 | 7.5 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 9.3 | 9.74 | 4.67 |

| 6 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 8.7 | 8.78 | 4.30 |

| 7 | 8.0 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 4.56 |

TP: total proteins.

Our study indicates that calcemia correction for albumin is more reliable for correctly diagnosing hypocalcemia.10 The cases presented reflect the influence of protein/albumin upon the calcium levels, as previously reported in the literature, mainly in patients with renal failure.6 This may result in an incorrect diagnosis, which in some cases could lead to the provision of TPN with more calcium than necessary. Routine biochemical testing usually reports total calcium levels and protein-corrected levels, but not albumin-corrected or ionic calcium levels. However, there is still controversy in the literature regarding the best method for measuring plasma calcium, with significant differences in terms of costs and clinical sensitivity.8

We conclude that it is essential to accurately determine calcemia in patients receiving TPN as well as in all hospitalized patients in general. It is therefore advisable to request albumin in the laboratory tests and, in the event of doubt, to determine ionic calcium, particularly in patients with alkalosis and/or altered renal function. If albumin or blood gases are not immediately available, the laboratory test results should be examined with caution, especially if the reported calcium concentration is <8mg/dl. In such a case, the clinical condition of the patient should be prioritised, TPN being supplemented with calcium only in the presence of symptoms of hypocalcemia. However, while the study suggests that calcium correction for albumin is more useful in clinical practice, and specifically for adjusting parenteral nutrition, than correction for proteins, studies involving larger samples are needed to consolidate these findings.

Financial supportThe present study has received no specific support from public, commercial or non-profit sources.

Please cite this article as: García L, Fernández M, Bengoa N, Pintor R, Arrieta F. Nutrición parenteral: albúmina versus proteínas totales en la valoración del calcio plasmático para ajustar la nutrición parenteral: a propósito de una serie de casos. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:272–274.