To use Google Trends to explore the trends of interest of the Spanish population regarding information related to different types of diets, focused on those that are popular and with evidence-based studies, over the last 10 years.

Material and methodsThe search trends referred to the terms “Mediterranean diet”, “ketogenic diet”, “low fat diet”, “intermittent fasting” and “vegan diet” were analyzed. The relative search volumes (RSV) of the terms were compared. The direction of the trend was studied using the Spearman's correlation coefficient (SC).

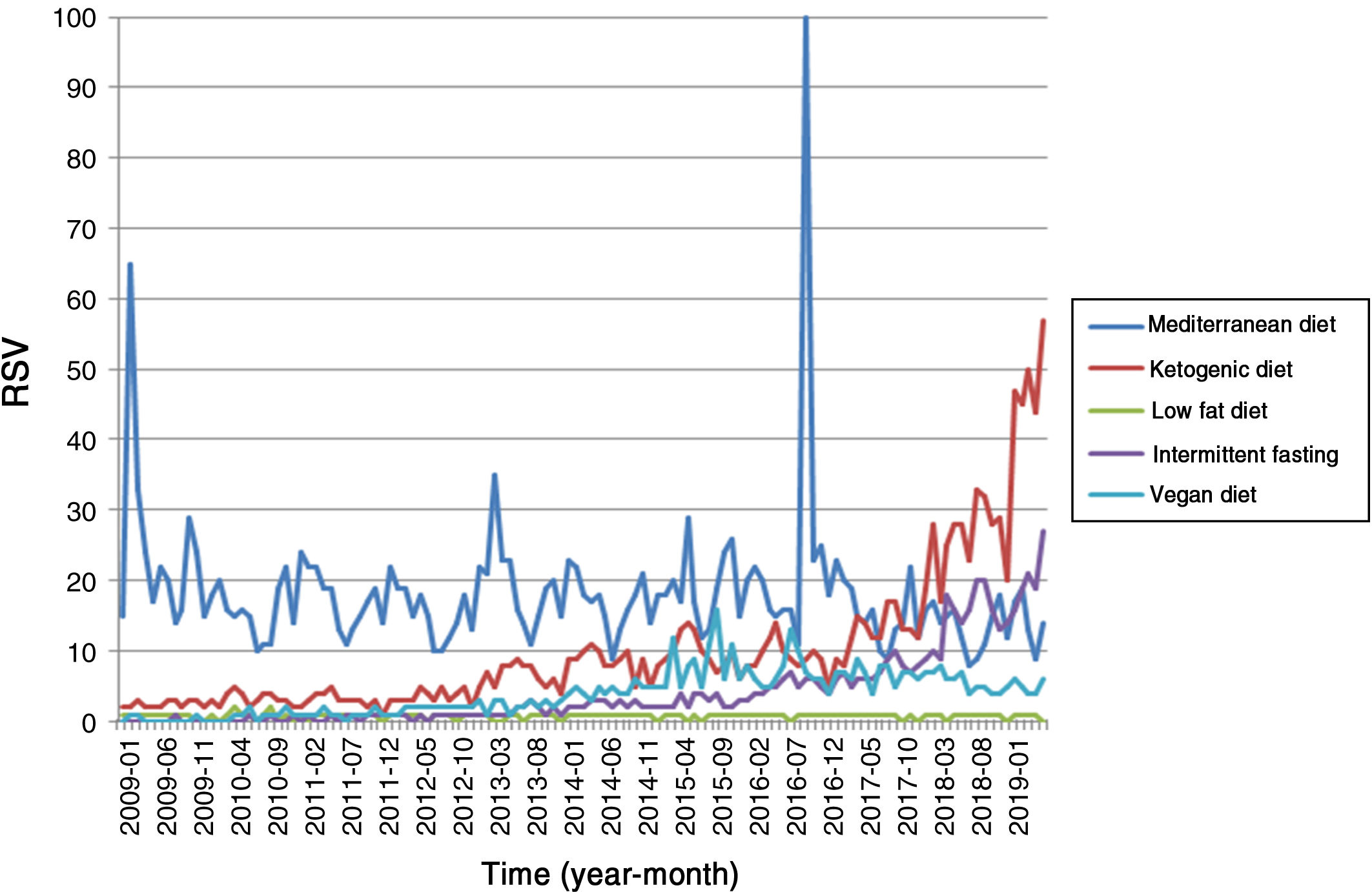

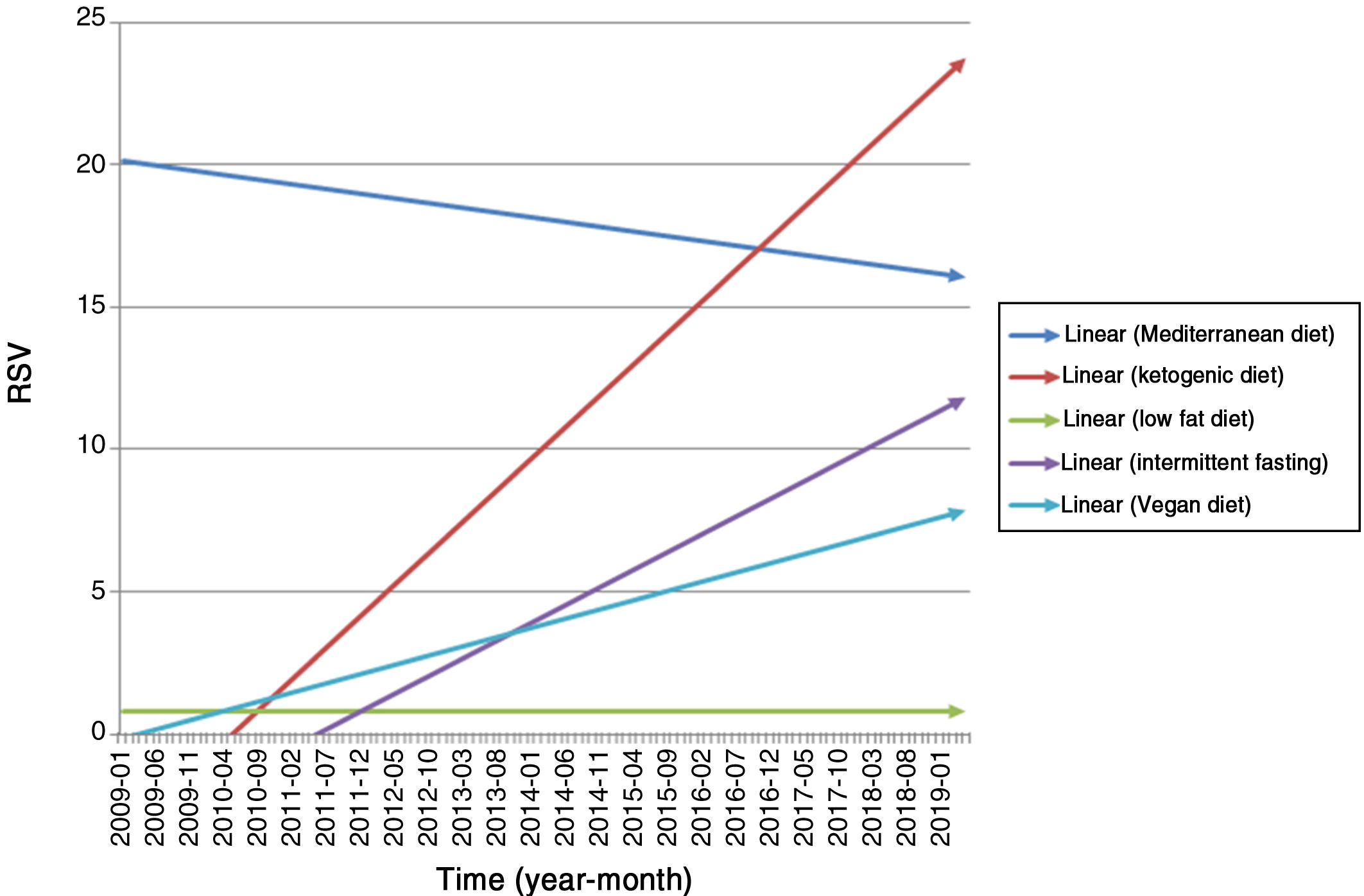

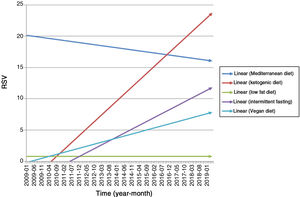

Results“Mediterranean diet” was the most widely searched term, with a median RSV of 16 (interquartile range [IQR] 6; range 8–100), though it exhibited a decreasing chronological trend (SC = −0.216). It was followed by “ketogenic diet”, with an RSV of 8 (IQR 9; range 1–57); “vegan diet”, with an RSV of 4 (IQR 5; range 0–16); “intermittent fasting”, with an RSV of 2 (IQR 5; range 0–27), and “low fat diet”, with an RSV of 1.16 (IQR 0; range 0–2). The term with the best correlation over time was “intermittent fasting” (SC = 0.96), followed by “ketogenic diet” (SC = 0.91) and “vegan diet” (SC = 0.85).

ConclusionsIn Spain, the interest of the population in information about the Mediterranean diet is greater than for other diets. However, in recent years there has been a progressive increase in interest (measured as RSV) in other diets such as the ketogenic diet, vegan diet or intermittent fasting, and there has been a decrease in interest in the Mediterranean diet. The low fat diet does not generate interest in the Spanish population.

Explorar a través Google Trends las tendencias del interés de la población española sobre información relacionada con diferentes tipos de dietas, focalizadas en las más populares y con estudios de evidencia, a lo largo de los últimos 10 años.

Material y métodoSe analizaron las tendencias de búsqueda de los términos «dieta mediterránea», «dieta cetogénica», «dieta baja en grasas», «ayuno intermitente» y «dieta vegana». El volumen relativo de búsqueda (VRB) de cada término fue comparado. La dirección de la tendencia se estudió mediante la correlación de Spearman (CS).

ResultadosEl término «dieta mediterránea» fue el más buscado, con una mediana de VRB de 16 (rango intercuartil [RI] 6; rango 8−100), aunque siguió una tendencia cronológica decreciente (CS = −0,216). Le siguieron «dieta cetogénica», con VRB de 8 (RI 9; rango 1–57); «dieta vegana», con VRB de 4 (RI 5; rango 0–16); «ayuno intermitente», con VRB de 2 (RI 5; rango 0–27), y «dieta baja en grasas», con VRB de 1,16 (RI 0; rango 0–2). El término con mejor correlación a lo largo del tiempo fue «ayuno intermitente» (CS = 0,96), seguido de «dieta cetogénica» (CS = 0,91) y «dieta vegana» (CS = 0,85).

ConclusiónEn España, el interés de la población sobre la información acerca de la dieta mediterránea es mayor que para otras dietas. Sin embargo, en los últimos años se ha producido un incremento progresivo en el interés, medido como VRB, en otras dietas, como la dieta cetogénica, la dieta vegana o el ayuno intermitente, y se ha producido una reducción en el interés por la dieta mediterránea. La dieta baja en grasas no genera interés en la población española.

In recent years, scientific bodies, professionals in the field of nutrition, and the Spanish National Health Service (Sistema Nacional de Salud [SNS]) have all sought to consolidate healthy lifestyle and eating habits, in particular by promoting the Mediterranean diet1 following the publication of the PREDIMED study (Prevention with the Mediterranean Diet), in which adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with lower cardiovascular risk.2 However, the real impact of these campaigns and the interest they generate among the public are not known.

New tools are emerging in the era of Big Data to facilitate healthcare research. One form of Big Data is that which is accumulated in the course of online search activities.3,4 Data from Internet searches can provide valuable information about the epidemiological patterns of certain diseases, as well as the behavior and interests of the population.3,4 One tool that allows Internet users to interact with search data is Google Trends, a free and publicly accessible online portal by Google Inc. Google Trends scans a portion of the 3000 million daily Google searches and provides data on geospatial and time patterns in search volumes under the terms specified by the user.5

Previous studies have used Google Trends to monitor overall suicide risk,6 determine public interest in cancer screening,7 track seasonal patterns in urinary tract infections8 or assess the use of infiltrations in osteoarthritis.9 In the field of nutrition, search trends referring to bariatric surgery techniques have been studied. Rahiri et al.10 observed a decrease in the search terms "gastric band" versus "gastric sleeve", and these results were reproduced worldwide.11 Tkachenko et al.12 in turn studied how Google Trends may be useful for detecting early signs of diabetes by generating combinations of keywords. In relation to diet, a study has investigated the annual variation in Internet searches using Google Trends in the United States, referring to the term “diet”. The study found that searches conform to a constant 12 month linear model, reaching a peak in January (after New Year’s Eve) and then decreasing linearly until the process is repeated the following January.13 However, no articles were found evaluating searches on Google Trends for certain diets or assessing which diets are most searched for by users. The previous studies addressed trends globally or in countries other than Spain. We therefore considered there was a need for an individualized study focusing on Spain.

Our aim was to use Google Trends to explore the trends of interest to the Spanish population regarding information on different types of diet, focusing on the most popular diets and on evidence-based studies published over the past 10 years.

Material and methodsIn order to analyze the trend in online searches for information on certain diets on the part of the Spanish population, one of the authors (IM), on 2 June 2019, used the software tool Google Trends in Spanish14 to analyze the data corresponding to the previous 10 years (from June 2009 to June 2019).

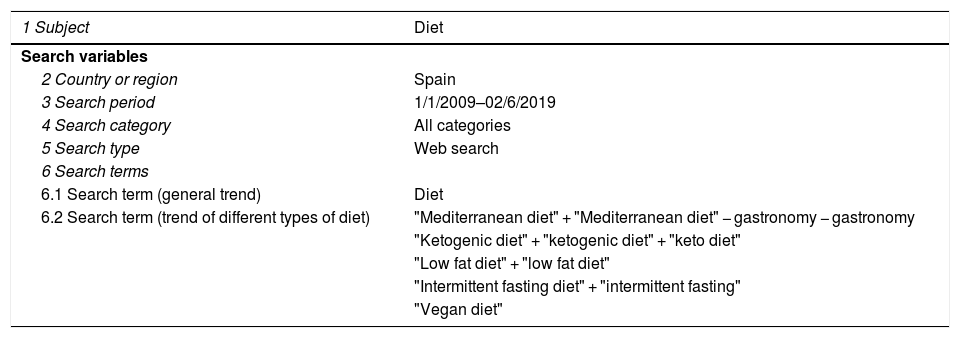

Search strategy“Spain” was selected as the country of interest, and “all categories” was selected since interest was general. The main search term was “diet”, together with combinations of the different possible diets. The method proposed by Nuti et al.3 was used to improve the reproducibility of our study (Table 1).

Checklist of search specifications.

| 1 Subject | Diet |

|---|---|

| Search variables | |

| 2 Country or region | Spain |

| 3 Search period | 1/1/2009–02/6/2019 |

| 4 Search category | All categories |

| 5 Search type | Web search |

| 6 Search terms | |

| 6.1 Search term (general trend) | Diet |

| 6.2 Search term (trend of different types of diet) | "Mediterranean diet" + "Mediterranean diet" − gastronomy − gastronomy |

| "Ketogenic diet" + "ketogenic diet" + "keto diet" | |

| "Low fat diet" + "low fat diet" | |

| "Intermittent fasting diet" + "intermittent fasting" | |

| "Vegan diet" |

Checklist proposed by Nuti et al.3.

In Google Trends, the primary outcome variable is the so-called “relative search volume” (RSV), which represents the search rate (on a 0–100 scale) for a specific term in relation to the total of selected searches (maximum 5 comparisons). The data descriptions allow evaluations of rates of change and comparisons between search terms. The software tool provides the numerical value of the RSV for each time interval of those search terms that meet a minimum volume threshold. The search results are proportional to the time and geographic location of a search according to the following process15:

- 1)

At each timepoint, the absolute volume of data is divided by the total searches of the geographic region in the time interval it represents, to compare relative popularity. If this were not done, the locations with the greatest volume of searches would always appear in the first places.

- 2)

The RSV value is then obtained. To this end, the numbers resulting from the previous process are scaled from 0 to 100, based on the proportion of a given term with respect to the total searches referring to all the terms.

- 3)

Exclusion is made of those searches performed for terms with a very low search volume, or made by very few users, which are shown with a value "0". Likewise, searches performed by the same person repeatedly over a short period of time are also eliminated.

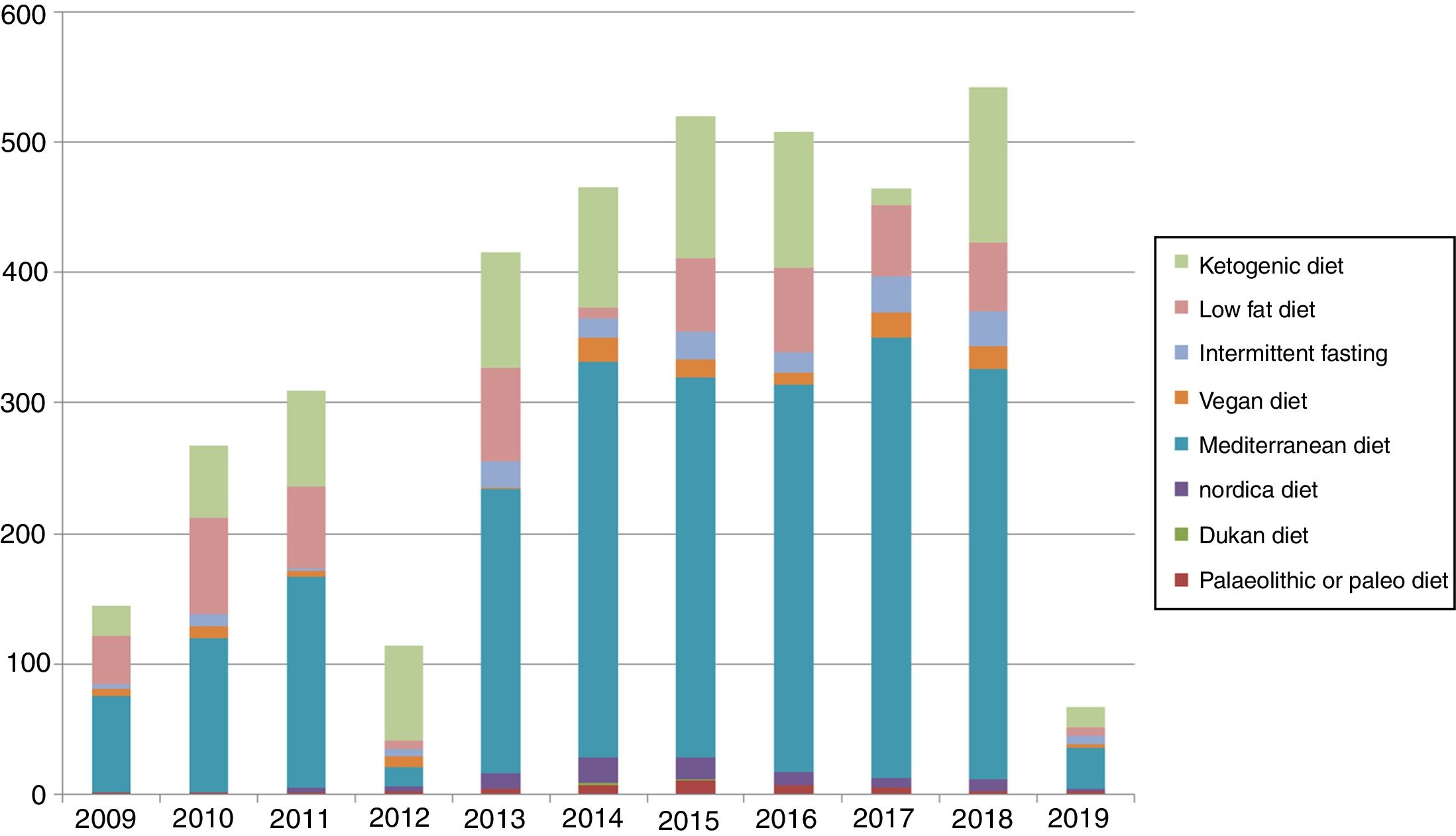

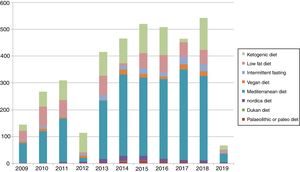

In order to determine the 5 diets to be compared, based on the general term "diet", we identified the most frequent related searches in Google. We were interested in knowing whether the most popular diets on Google had scientific evidence to support them. It was assumed that the diets with a greater number of publications in PubMed would serve as the cut-off point. For this reason we analyzed the timelines of the PubMed searches over the previous 10 years, and studied the number of publications that included the terms “Mediterranean diet”, “ketogenic diet”, “paleo diet”, “vegan diet”, “intermittent fasting”, “Dukan diet” or “Nordic diet” in the title or abstract. The terms “Mediterranean diet”, “ketogenic diet”, “vegan diet” and “intermittent fasting” were the most popular and were selected. The term “low fat diet” was added to the search, for although it had a low number of Google searches and was not among the most popular diets, it featured in a large number of publications over this period (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysisTrends were analyzed for each of the terms according to their RSV value. The RSV values for each term are presented as the median, interquartile range (IQR) and total range. Data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. All trends were evaluated by observing the correlation between time and RSV, based on the Spearman coefficient (SC), being very weak or absent for values of 0–0.25, weak for 0.26–0.50, moderate for 0.51–0.75, and strong for values of ≥0.76. The RSV values between the different terms were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test, and paired comparisons were made with Bonferroni correction. Statistical significance was considered for p < 0.05 in all cases.

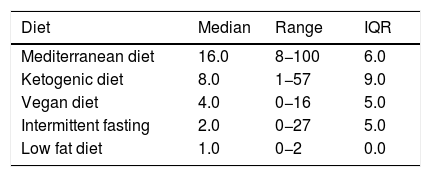

ResultsThe term with the greatest RSV was "Mediterranean diet" (p < 0.001). Following "Mediterranean diet", and in decreasing order of interest, we found "ketogenic diet", "vegan diet", "intermittent fasting", and finally "low fat diet" (Table 2).

Relative search volume (RSV) values for different diets over a period of 10 years.

| Diet | Median | Range | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean diet | 16.0 | 8−100 | 6.0 |

| Ketogenic diet | 8.0 | 1−57 | 9.0 |

| Vegan diet | 4.0 | 0−16 | 5.0 |

| Intermittent fasting | 2.0 | 0−27 | 5.0 |

| Low fat diet | 1.0 | 0−2 | 0.0 |

Ordered from highest to lowest, according to the median relative search volume (RSV).

IQR: interquartile range.

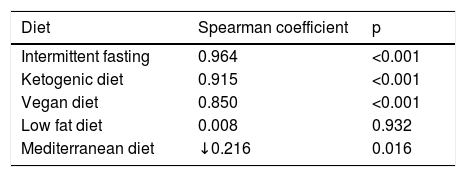

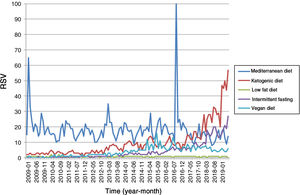

However, on examining the search trends over the previous 10 years (Fig. 2), we observed a very weakly descending trend in the term “Mediterranean diet”. The term “low fat diet” showed no changes, with a zero trend. On the other hand, the terms "ketogenic diet", "intermittent fasting" and "vegan diet" showed a strong increasing search trend (Fig. 3). The term "intermittent fasting" showed the best direct correlation with time, followed by "ketogenic diet" and "vegan diet" (Table 3).

Correlation of relative search volume (RSV) of the different diets over time.

| Diet | Spearman coefficient | p |

|---|---|---|

| Intermittent fasting | 0.964 | <0.001 |

| Ketogenic diet | 0.915 | <0.001 |

| Vegan diet | 0.850 | <0.001 |

| Low fat diet | 0.008 | 0.932 |

| Mediterranean diet | ↓0.216 | 0.016 |

Ordered from highest to lowest, according to the Spearman correlation coefficient.

Our results indicate that the interest of the Spanish population in Internet searching for the Mediterranean diet is high, it having been the most consulted diet over the last 10 years. However, despite the growing scientific evidence regarding its benefits in terms of cardiovascular disease prevention,2 the prevention or improvement of diabetes control,16 lipid profile17 and even the reduction of all-cause mortality,18 the interest it generates exhibits a negative trend. This could be because such information is not adequately conveyed or is unable to stimulate sufficient interest among Internet users.

On the other hand, we observed that population interest in certain diets has increased significantly over the last 10 years. Specifically, intermittent fasting, followed by the ketogenic diet and finally the vegan diet, have generated increasing interest among the population, with a progressive increase in the number of searches over the evaluated time period. This observation is accompanied by the appearance in the last 10 years of scientific publications in favor of these diets.19–21

It must be emphasized that Internet searches in the education of the population, and particularly of patients, play a very important role. Specifically, access to health information is particularly important in relation to diseases which can be self-diagnosed, such as overweight or obesity. Access to websites containing quality information on types of diet is particularly important for such patients, who may feel that the information provided by their physician is incomplete, or who are unable to access specialist care (waiting lists are estimated to range from 4 months to 2 years22) and therefore resort to the Internet as their primary source of information. Lewis et al.23 found that the Internet is a convenient source of support and information for obese people. However, many resort to the same failed online solutions, e.g., fad diets; it is therefore important to evaluate the accuracy of the information which patients find online. A recent study showed that the quality of information related to the Mediterranean diet is highly variable, and is often poor. The authors concluded that anyone interested in the Mediterranean diet should seek advice from physicians or dieticians.24 Based on the above, validating the quality of the information provided in relation to the different types of diet through search engines is an important step in improving the education of the population. In this respect, it should be the task of health professionals, and especially of dieticians, to help people to adequately search for and assess nutritional information online.25

The increased interest we have observed in diets other than the Mediterranean diet may be related to the profile of the users who perform Internet searches. A number of studies have found that younger people with a higher educational level and income are more likely to use health applications. In turn, the use of such applications is associated with a personal intention to change diet and comply with the recommendations referring to physical activity.26–28 This could explain why there are population groups that seek a more novel dietary alternative than the more traditional approaches, such as the Mediterranean diet. However, Google Trends does not provide information on the profile of the user making the search, and there are no national registries providing data on the type of diets that are followed or predominantly prescribed.

The present study has limitations. The results may not fully consider those with limited resources or poor access to the Internet. We consider that our selection of the 5 diets to be compared was the correct one, since these are the diets with the greatest number of publications available among those most consulted by online users. In this regard, there are a great number of diets with different purposes, and the limitations of the tool did not allow us to compare all of them. Likewise, it is difficult to quantify the number of people who finally adhere to some type of diet among those considered in our study, since we know of no national registry allowing us to study this subject. Therefore, we cannot correlate the search activity to the actual use of diets and adherence to them. However, it should be noted that the aim of this study was to reflect the interests of the population.

ConclusionsIn Spain, interest in information regarding the Mediterranean diet is greater than interest in other types of diet. However, in recent years there has been a gradual increase in interest (measured as RSV) in other types of diet such as the ketogenic diet, vegan diet or intermittent fasting, and a decrease in interest in the Mediterranean diet. The low fat diet does not generate interest among the Spanish population.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Modrego-Pardo I, Solá-Izquierdo E, Morillas-Ariño C. Tendencia de la población espa˜nola de búsqueda en internet sobre información relacionada con diferentes dietas. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endinu.2019.11.003