To assess the modifying effect of marital status on social and gender inequalities in mortality from diabetes mellitus (DM) in Andalusia.

Material and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted using the Andalusian Longitudinal Population Database. DM deaths between 2002 and 2013 were analyzed by educational level and marital status. Age-adjusted rates (AARs) and mortality rate ratios (MRRs) were calculated using Poisson regression models, controlling for several social and demographic variables. The modifying effect of marital status on the association between educational level and DM mortality was evaluated by introducing an interaction term into the models. All analyses were performed separately for men and women.

ResultsThere were 18,158 DM deaths (10,635 women and 7523 men) among the 4,229,791 people included in the study. The risk of death increased as the educational level decreased. Marital status modified social inequality in DM mortality in a different way in each sex. Widowed and separated/divorced women with the lowest educational level had the highest MRRs, 5.1 (95% CI: 3.6–7.3) and 5.6 (95% CI: 3.6–8.5) respectively, while single men had the highest MRR, 3.1 (95% CI: 2.7–3.6).

ConclusionsEducational level is a key determinant of DM mortality in both sexes, and is more relevant in women, while marital status also plays an outstanding role in men. Our results suggest that in order to address inequalities in DM mortality, the current focus on individual factors and self-care should be extended to interventions on the family, the community, and the social contexts closest to patients.

Evaluar el efecto modificador del estado civil sobre las desigualdades sociales y de género en la mortalidad por diabetes mellitus (DM) en Andalucía.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal a partir de la Cohorte Censal 2001 de Andalucía. Se estudiaron defunciones por DM entre 2002 y 2013 según nivel de estudios y estado civil. Se calcularon tasas de mortalidad ajustadas por edad (TA) y razones de tasas de mortalidad (RTM) mediante modelos de regresión de Poisson, controladas por otras variables sociodemográficas. Se evaluó el efecto modificador del estado civil incorporando a los modelos un término de interacción. Todos los análisis se realizaron separadamente para hombres y mujeres.

ResultadosSobre un total de 4.229.791 sujetos se registraron 18.158 muertes por DM (10.635 mujeres y 7.523 hombres). A medida que disminuye el nivel educativo aumenta el riesgo de muerte. El estado civil modifica la desigualdad social en la mortalidad por DM de forma diferente en cada sexo. Las mujeres viudas y separadas/divorciadas con menor nivel de estudios presentan las mayores RTM: 5,1 (IC 95%: 3,6-7,3) y 5,6 (IC 95%: 3,6-8,5), respectivamente, mientras que los hombres solteros tienen la RTM más elevada: 3,1 (IC 95%: 2,7-3,6).

ConclusionesEl nivel de estudios es un determinante fundamental de la mortalidad por DM en ambos sexos; su relevancia es mayor entre las mujeres, mientras que en los hombres también el estado civil es un factor clave. Para abordar las desigualdades en la mortalidad nuestros resultados sugieren que el énfasis actual en los factores individuales y el autocuidado debería extenderse hacia intervenciones sobre la familia, la comunidad y los contextos sociales más cercanos a los pacientes.

The growing importance of diabetes mellitus (DM) in relation to the global disease burden1 has favored the search for other determining factors beyond obesity and physical exercise. Socioeconomic status has been investigated in many studies, where it has been shown to be related to DM prevalence, incidence and mortality, and to the incidence of associated complications.2 In the evaluation of social inequalities in DM, the most widely used measures of individual socioeconomic status have been educational level, occupation, income and—from a contextual perspective—deprivation indices. Regarding social inequality the trend observed in most studies indicates that the lower the educational level3 or the greater the deprivation index,4 the higher the frequency of DM. Another consistent finding in the literature is that relative inequalities are more pronounced in women5—a fact that has been attributed by some authors to the greater prevalence of obesity and sedentary habits among females,3 with both of these factors being more common among the lower socioeconomic levels. In contrast, other investigators consider this situation to be a consequence of psychosocial and occupational factors.6

The socioeconomic status of a patient with DM is also associated with the mechanisms related to the evolution of the disease, such as accessibility to healthcare services, the quality of care, knowledge of the disease, or capability in following the medical instructions received.7 Furthermore, in DM as in other chronic diseases, social support in the immediate daily setting of the patient is crucial for maintaining the norms and behavior aimed at controlling the disease, particularly those related to eating habits.8

One of the factors to be taken into consideration with regard to social support in the immediate daily setting is marital status. Accordingly, the lesser mortality risk seen in married individuals, particularly males, could be explained in part by a protective effect related to the greater social support conferred by marriage.9 On the other hand, marriage, through the mutual care afforded by the couple (i.e., adherence to diet instructions, laboratory tests, treatment compliance, psychological support), in turn promotes healthy lifestyles and is associated with greater healthcare coverage.10,11 In turn, there may be a selection effect regarding those individuals who are physically and psychologically healthier and/or with healthier lifestyles, to the detriment of those subjects with health problems, who are more likely to remain single, divorce or become separated, or not remarry in the event of widowhood or divorce or separation.12 Among non-married individuals (single, widowed, divorced or separated people), and depending on the cause of death, gender and/or age, discordant results have been published regarding which marital status is associated with an increased mortality risk.13

In general, single or widowed males suffer greater mortality, though the differences with respect to women become attenuated with the increasing age of the study population. The analysis of marital status, in terms of its influence in designating differentiated gender roles, can help us to gain more in-depth knowledge of the causes of the gender inequalities seen in DM.14 Although mortality due to diabetes has progressively decreased in Andalusia (Spain) in recent years, fundamentally at the expense of a reduction in premature death, with rates similar to those found at Spanish national level,15 its distribution according to socioeconomic status and social support is not clear.

The objectives of this study are: (1) to analyze social inequality in mortality due to DM; and (2) to evaluate the possible modifying effect of marital status upon the social and gender inequalities in DM mortality in Andalusia.

Material and methodsData source (deaths and sociodemographic variables)The Andalusian Longitudinal Population Database (Base de Datos Longitudinal de Población de Andalucía [BDLPA]) was used.16 Created in 2002 by the Andalusian Institute of Statistics and Cartography (Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía [IECA]), this database incorporates information from the Andalusian Population and Homes Census of 2001 (Censo de Población y Viviendas de Andalucía de 2001), the Natural Population Movement (Movimiento Natural de la Población [MNP]) mortality statistics, and the residential variations posterior to the census date documented in the municipal census records. The study reference population comprised the individuals registered in the Population and Homes Census of 2001 (7,357,547), entered in the Municipal Inhabitants Census (Padrón Municipal de Habitantes [PMH]) of a municipality in Andalusia and who resided in Andalusia on 1 January 2002 (7,202,794), representing 97.9% of those in the census. In the course of follow-up, each member of the Census Cohort of 2001 contributed a certain number of persons/year of exposure or at risk. The end of follow-up could be due to: (a) death, as registered in the MNP and/or PMH; (b) emigration outside Andalusia; or (c) the end of the study census (31 December 2013, in our analysis).

The subjects included in the study were those individuals aged 30 years or older and residing in Andalusia between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2013, representing a total of 4,229,791 persons. At 30 years of age, most of them had already completed their education.

VariablesThe dependent variable was death due to DM (ICD-10 codes: E10-14) registered in the BDLPA between 2002 and 2013 (both inclusive). The independent variables (measured on the census date) were: (1) educational level (maximum educational level reached, classified into four categories: third grade (first, second and third cycle), second grade (first and second cycle), first grade, and incomplete studies, no education or illiteracy; (2) marital status, classified into four categories: married, single, separated or divorced, and widowed; (3) age, classified into 12 biweekly groups (30–34;...; 85 and +); (4) the census, based on the province of residency; (5) home ownership: own home or others; and (6) activity status: receiving some type of teaching, employed, unemployed, pensioner, performing or helping in domestic work, and other situations.

Statistical analysisThe DM mortality rates in Andalusia (×100,000 persons/year) were calculated, with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), controlling for age by the direct method to the European standard population (age adjusted rates [AARs]). The rates were first estimated separately according to educational level and marital status, and subsequently according to educational level for each marital status category.

In order to measure the relative inequalities, we calculated the mortality rate ratios (MRRs) and their corresponding 95% CI according to educational level and marital status, controlling for age, the census based province of residency, home ownership and activity status. These measures were calculated by adjusting Poisson regression models, with robust estimation of the standard errors. In order to assess the modifying effect of marital status upon MRRs according to educational level, we entered an interaction term between both variables in the Poisson regression models, taking mortality among married individuals with third grade educational level as the reference category. The persons/year of exposure were included as offset. All the analyses were made separately for men and women. The Stata IC 11® package was used for the calculations.

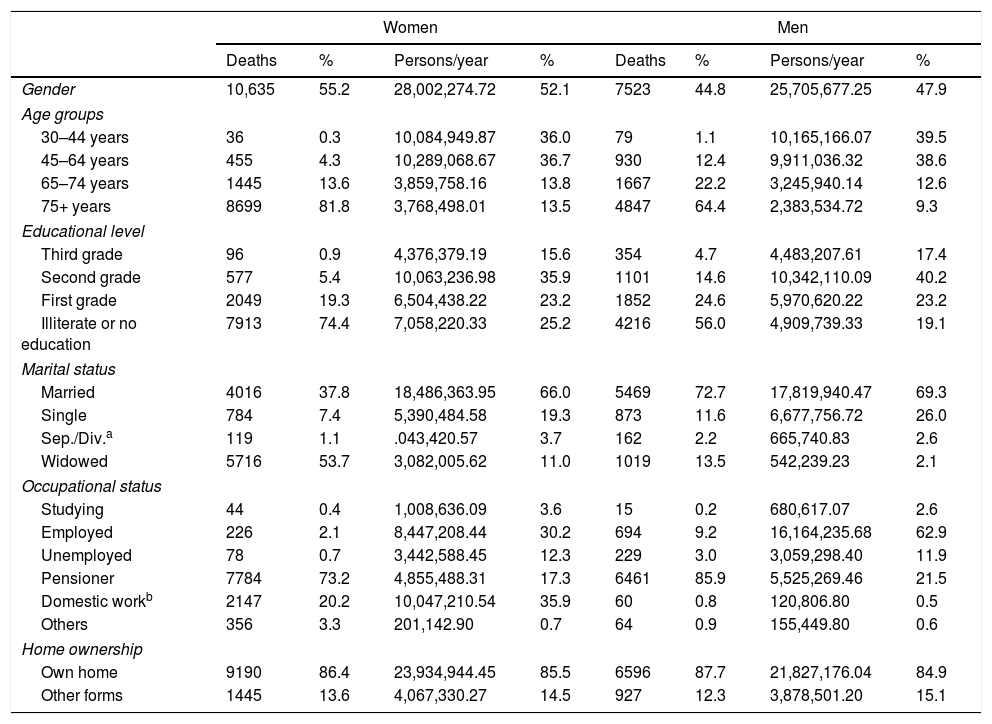

ResultsTable 1 summarizes the frequency data referring to deaths and persons/year at risk in the different categories of the analyzed independent variables. In the period 2002–2013 a total of 18,158 deaths due to DM were recorded: 10,635 in women (55.2%) and 7523 in men. These figures in turn represented 3.3% and 2.1% of all deaths in Andalusia during that period (in the population aged 30 years and older), respectively. Only 6.3% of the women and 19.3% of the men that died had reached secondary or higher education level. Of note is the 74.4% rate of illiteracy or no education among the women. A total of 72.7% of the men were married and 13.5% were widowed at the time of death, while the respective figures in women were 37.8% and 53.7%.

Deaths due to diabetes mellitus (≥30 years) in Andalusia, 2002–2013. General characteristics of the study subjects. Census cohort-2001 (BDLPA).

| Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | % | Persons/year | % | Deaths | % | Persons/year | % | |

| Gender | 10,635 | 55.2 | 28,002,274.72 | 52.1 | 7523 | 44.8 | 25,705,677.25 | 47.9 |

| Age groups | ||||||||

| 30–44 years | 36 | 0.3 | 10,084,949.87 | 36.0 | 79 | 1.1 | 10,165,166.07 | 39.5 |

| 45–64 years | 455 | 4.3 | 10,289,068.67 | 36.7 | 930 | 12.4 | 9,911,036.32 | 38.6 |

| 65–74 years | 1445 | 13.6 | 3,859,758.16 | 13.8 | 1667 | 22.2 | 3,245,940.14 | 12.6 |

| 75+ years | 8699 | 81.8 | 3,768,498.01 | 13.5 | 4847 | 64.4 | 2,383,534.72 | 9.3 |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Third grade | 96 | 0.9 | 4,376,379.19 | 15.6 | 354 | 4.7 | 4,483,207.61 | 17.4 |

| Second grade | 577 | 5.4 | 10,063,236.98 | 35.9 | 1101 | 14.6 | 10,342,110.09 | 40.2 |

| First grade | 2049 | 19.3 | 6,504,438.22 | 23.2 | 1852 | 24.6 | 5,970,620.22 | 23.2 |

| Illiterate or no education | 7913 | 74.4 | 7,058,220.33 | 25.2 | 4216 | 56.0 | 4,909,739.33 | 19.1 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 4016 | 37.8 | 18,486,363.95 | 66.0 | 5469 | 72.7 | 17,819,940.47 | 69.3 |

| Single | 784 | 7.4 | 5,390,484.58 | 19.3 | 873 | 11.6 | 6,677,756.72 | 26.0 |

| Sep./Div.a | 119 | 1.1 | .043,420.57 | 3.7 | 162 | 2.2 | 665,740.83 | 2.6 |

| Widowed | 5716 | 53.7 | 3,082,005.62 | 11.0 | 1019 | 13.5 | 542,239.23 | 2.1 |

| Occupational status | ||||||||

| Studying | 44 | 0.4 | 1,008,636.09 | 3.6 | 15 | 0.2 | 680,617.07 | 2.6 |

| Employed | 226 | 2.1 | 8,447,208.44 | 30.2 | 694 | 9.2 | 16,164,235.68 | 62.9 |

| Unemployed | 78 | 0.7 | 3,442,588.45 | 12.3 | 229 | 3.0 | 3,059,298.40 | 11.9 |

| Pensioner | 7784 | 73.2 | 4,855,488.31 | 17.3 | 6461 | 85.9 | 5,525,269.46 | 21.5 |

| Domestic workb | 2147 | 20.2 | 10,047,210.54 | 35.9 | 60 | 0.8 | 120,806.80 | 0.5 |

| Others | 356 | 3.3 | 201,142.90 | 0.7 | 64 | 0.9 | 155,449.80 | 0.6 |

| Home ownership | ||||||||

| Own home | 9190 | 86.4 | 23,934,944.45 | 85.5 | 6596 | 87.7 | 21,827,176.04 | 84.9 |

| Other forms | 1445 | 13.6 | 4,067,330.27 | 14.5 | 927 | 12.3 | 3,878,501.20 | 15.1 |

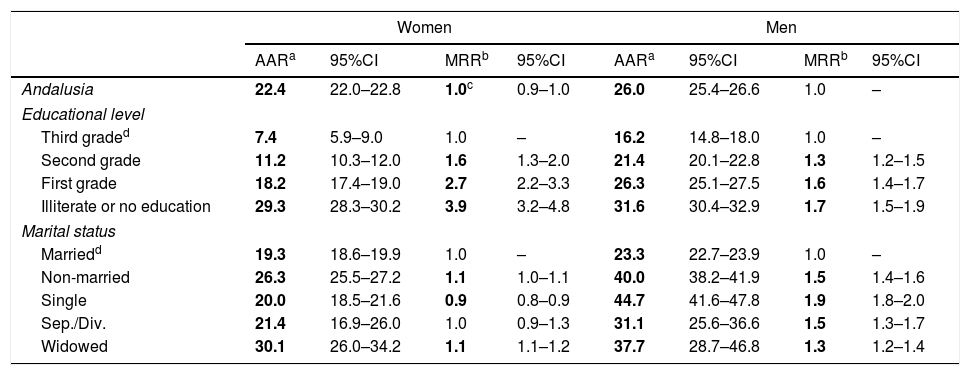

Table 2 shows the adjusted mortality rates according to educational level and marital status, for each gender. The respective male and female mortality rates among illiterate individuals and subjects without education were 29.3 (95% CI: 28.3–30.2) and 31.6 (95% CI: 30.4–32.9), while in those with third grade education the figures were 7.4 (95% CI: 5.9–9.0) and 16.2 (95% CI: 14.5–18.0) per 100,000 persons/year. The corresponding rates for married and non-married women were 19.3 (95% CI: 18.6–19.9) and 26.3 (95% CI: 25.5–27.2), while in the case of men the figures were 23.3 (95% CI: 22.7–23.9) and 40.0 (95% CI: 38.2–41.9). In all marital status categories men had higher AARs than women. The MRR in single versus married men was 1.9 (95% CI: 1.8–2.0), while in single women it was 0.9 (95% CI: 0.8–0.9).

Mortality due to diabetes mellitus in Andalusia, 2002–2013. Age adjusted rates and mortality rate ratios, according to educational level and marital status (≥30 years).

| Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AARa | 95%CI | MRRb | 95%CI | AARa | 95%CI | MRRb | 95%CI | |

| Andalusia | 22.4 | 22.0–22.8 | 1.0c | 0.9–1.0 | 26.0 | 25.4–26.6 | 1.0 | – |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Third graded | 7.4 | 5.9–9.0 | 1.0 | – | 16.2 | 14.8–18.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Second grade | 11.2 | 10.3–12.0 | 1.6 | 1.3–2.0 | 21.4 | 20.1–22.8 | 1.3 | 1.2–1.5 |

| First grade | 18.2 | 17.4–19.0 | 2.7 | 2.2–3.3 | 26.3 | 25.1–27.5 | 1.6 | 1.4–1.7 |

| Illiterate or no education | 29.3 | 28.3–30.2 | 3.9 | 3.2–4.8 | 31.6 | 30.4–32.9 | 1.7 | 1.5–1.9 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Marriedd | 19.3 | 18.6–19.9 | 1.0 | – | 23.3 | 22.7–23.9 | 1.0 | – |

| Non-married | 26.3 | 25.5–27.2 | 1.1 | 1.0–1.1 | 40.0 | 38.2–41.9 | 1.5 | 1.4–1.6 |

| Single | 20.0 | 18.5–21.6 | 0.9 | 0.8–0.9 | 44.7 | 41.6–47.8 | 1.9 | 1.8–2.0 |

| Sep./Div. | 21.4 | 16.9–26.0 | 1.0 | 0.9–1.3 | 31.1 | 25.6–36.6 | 1.5 | 1.3–1.7 |

| Widowed | 30.1 | 26.0–34.2 | 1.1 | 1.1–1.2 | 37.7 | 28.7–46.8 | 1.3 | 1.2–1.4 |

MRR: mortality rate ratio; AAR: age adjusted rate.

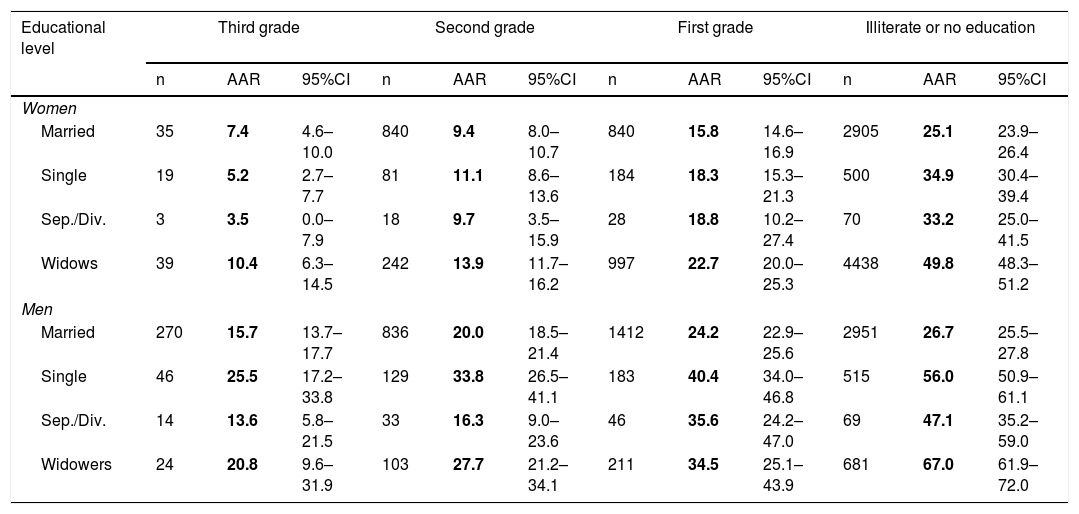

The mortality rates due to DM according to educational level for each marital status category are shown in Table 3. Of note were the rates of 66.99 (95% CI: 61.94–72.00) and 49.76 (95% CI: 48.30–51.22) in widowed men and women who were illiterate or had no education. In each marital status category the rates exhibited an inverse social gradient, being more pronounced among women.

Adjusted mortality rates due to diabetes mellitus in Andalusia, 2002–2013, according to educational level for each marital status category (≥30 years).

| Educational level | Third grade | Second grade | First grade | Illiterate or no education | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | AAR | 95%CI | n | AAR | 95%CI | n | AAR | 95%CI | n | AAR | 95%CI | |

| Women | ||||||||||||

| Married | 35 | 7.4 | 4.6–10.0 | 840 | 9.4 | 8.0–10.7 | 840 | 15.8 | 14.6–16.9 | 2905 | 25.1 | 23.9–26.4 |

| Single | 19 | 5.2 | 2.7–7.7 | 81 | 11.1 | 8.6–13.6 | 184 | 18.3 | 15.3–21.3 | 500 | 34.9 | 30.4–39.4 |

| Sep./Div. | 3 | 3.5 | 0.0–7.9 | 18 | 9.7 | 3.5–15.9 | 28 | 18.8 | 10.2–27.4 | 70 | 33.2 | 25.0–41.5 |

| Widows | 39 | 10.4 | 6.3–14.5 | 242 | 13.9 | 11.7–16.2 | 997 | 22.7 | 20.0–25.3 | 4438 | 49.8 | 48.3–51.2 |

| Men | ||||||||||||

| Married | 270 | 15.7 | 13.7–17.7 | 836 | 20.0 | 18.5–21.4 | 1412 | 24.2 | 22.9–25.6 | 2951 | 26.7 | 25.5–27.8 |

| Single | 46 | 25.5 | 17.2–33.8 | 129 | 33.8 | 26.5–41.1 | 183 | 40.4 | 34.0–46.8 | 515 | 56.0 | 50.9–61.1 |

| Sep./Div. | 14 | 13.6 | 5.8–21.5 | 33 | 16.3 | 9.0–23.6 | 46 | 35.6 | 24.2–47.0 | 69 | 47.1 | 35.2–59.0 |

| Widowers | 24 | 20.8 | 9.6–31.9 | 103 | 27.7 | 21.2–34.1 | 211 | 34.5 | 25.1–43.9 | 681 | 67.0 | 61.9–72.0 |

AAR: age-adjusted rate×100,000 persons/year, adjusted to the European standard population.

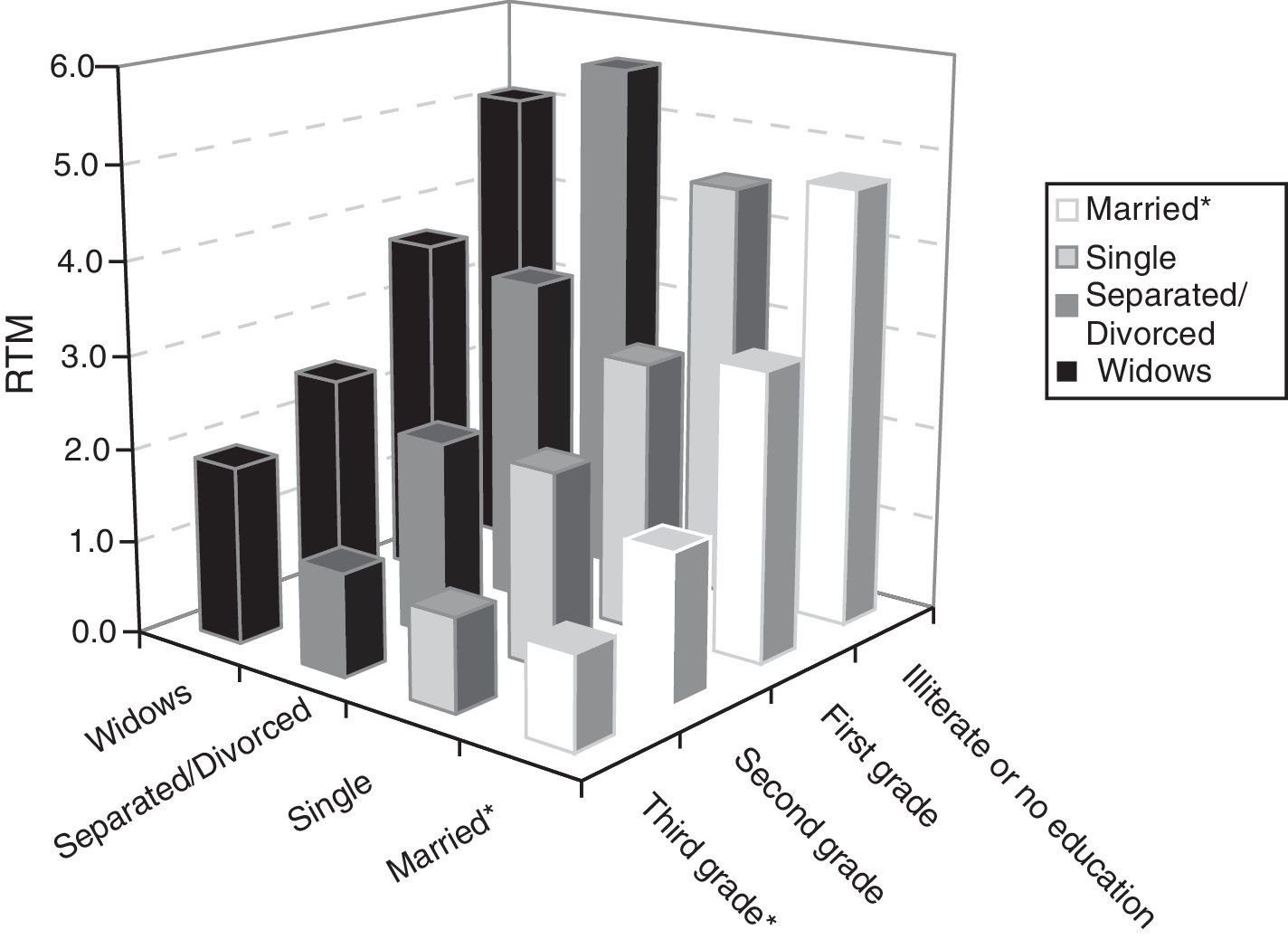

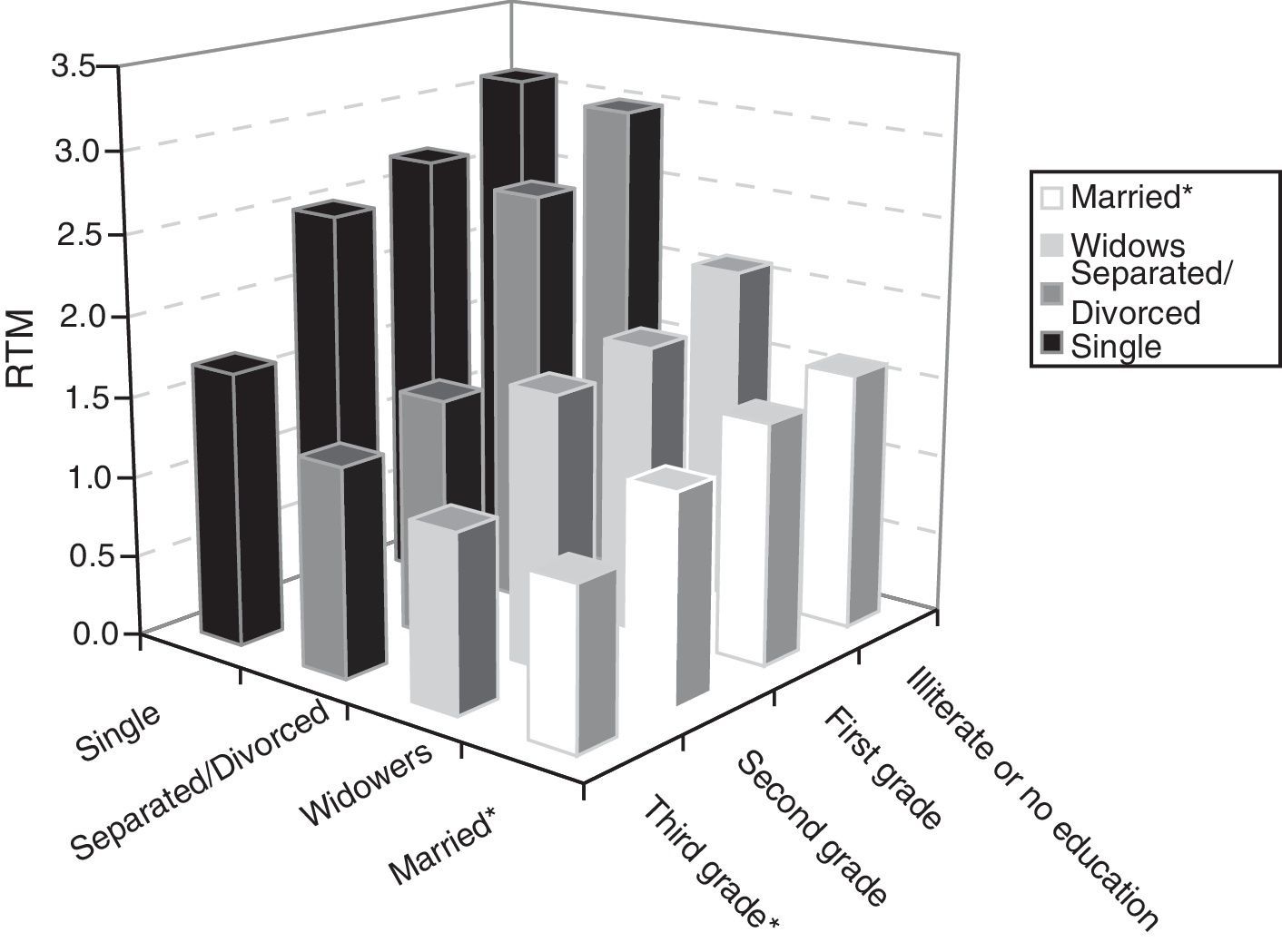

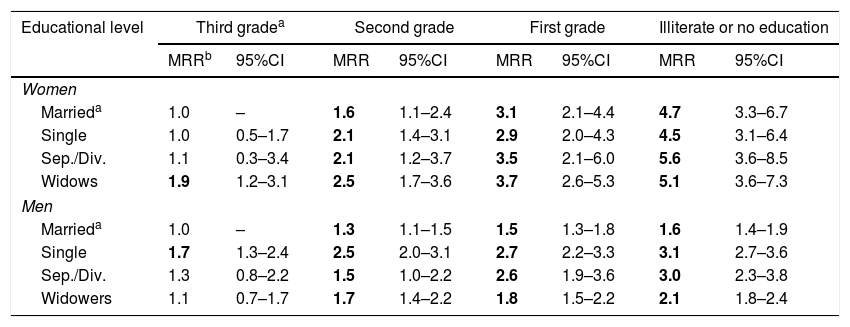

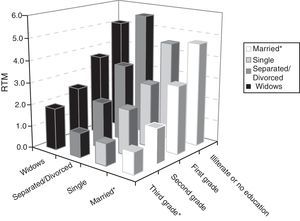

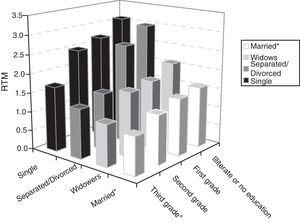

Table 4 (Figs. 1 and 2) describes the estimated MRRs and corresponding 95% CI for each gender referring to the modification of mortality risk according to educational level, with marital status, age adjusted estimates, province of residency, home ownership and activity status being taken into consideration. With regard to the married individuals with third grade education (reference category), we found that as the educational level decreased, the DM mortality risk increased in both males and females, with an MRR in widowed women of 1.9 (95% CI: 1.2–3.1), 2.5 (95% CI: 1.7–3.6), 3.7 (95% CI: 2.6–5.3) and 5.1 (95% CI: 3.6–7.3) for third, second and first grade education and illiteracy and no education, respectively. Separated or divorced individuals of both genders showed high MRRs, except those with third grade education.

Mortality rate ratios corresponding to diabetes mellitus in Andalusia, 2002–2013, according to the educational level for each marital status category (≥30 years).

| Educational level | Third gradea | Second grade | First grade | Illiterate or no education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRRb | 95%CI | MRR | 95%CI | MRR | 95%CI | MRR | 95%CI | |

| Women | ||||||||

| Marrieda | 1.0 | – | 1.6 | 1.1–2.4 | 3.1 | 2.1–4.4 | 4.7 | 3.3–6.7 |

| Single | 1.0 | 0.5–1.7 | 2.1 | 1.4–3.1 | 2.9 | 2.0–4.3 | 4.5 | 3.1–6.4 |

| Sep./Div. | 1.1 | 0.3–3.4 | 2.1 | 1.2–3.7 | 3.5 | 2.1–6.0 | 5.6 | 3.6–8.5 |

| Widows | 1.9 | 1.2–3.1 | 2.5 | 1.7–3.6 | 3.7 | 2.6–5.3 | 5.1 | 3.6–7.3 |

| Men | ||||||||

| Marrieda | 1.0 | – | 1.3 | 1.1–1.5 | 1.5 | 1.3–1.8 | 1.6 | 1.4–1.9 |

| Single | 1.7 | 1.3–2.4 | 2.5 | 2.0–3.1 | 2.7 | 2.2–3.3 | 3.1 | 2.7–3.6 |

| Sep./Div. | 1.3 | 0.8–2.2 | 1.5 | 1.0–2.2 | 2.6 | 1.9–3.6 | 3.0 | 2.3–3.8 |

| Widowers | 1.1 | 0.7–1.7 | 1.7 | 1.4–2.2 | 1.8 | 1.5–2.2 | 2.1 | 1.8–2.4 |

MRRs: mortality rate ratios.

Mortality rate ratios (MRRs) corresponding to diabetes mellitus in Andalusia, 2002–2013, according to the educational level for each marital status category (≥30 years). Women. *Reference category: married with third grade education (source data: see Table 4).

Mortality rate ratios (MRRs) corresponding to diabetes mellitus in Andalusia, 2002–2013, according to the educational level for each marital status category (≥30 years). Men. *Reference category: married with third grade education (source data: see Table 4).

The results of our study reveal the existence of social inequality in both men and women as regards mortality due to DM in Andalusia, with the observation of a clear inverse social gradient that was much more pronounced in women. The lower the educational level, the greater the DM mortality risk. Although for all marital status categories the mortality rates according to educational level were higher in males, the most pronounced social gradients were observed in women—particularly widows. In both genders, marital status modified the impact of educational level upon DM mortality. On taking married individuals with the highest educational level as the reference category, widowed women, single men and separated or divorced persons showed the highest mortality risk.

Despite the repeated observations in the literature on the relationship between marital status and mortality, the evaluation of the former as a possible modifier of the effect of socioeconomic status variables has been very limited to date, and to the best of our knowledge it has never been addressed in relation to mortality due to DM. The few studies that have examined this issue have found that being married and having a high educational level is associated with lesser mortality in general.17 In relation to causes of death such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, respiratory and infectious disorders, unmarried people show very high mortality risk levels, though the magnitude varies according to whether the individuals are widowed, single, or separated or divorced.18,19

Apart from the known greater relative inequality in mortality among women,10 our study adds the perspective of social inequality while taking into account the effect of marital status. In a chronic disease such as DM, therapeutic care and follow-up are crucial in order to avoid complications and to reduce patient mortality. The negative impact of an unfavorable economical situation is compounded by the effect of a marital status that favors poor control of the disease. Our results show that marital status, to the degree to which it conditions a greater or lesser presence of health-favoring factors in patients with DM, modifies the social inequality in the mortality risk due to DM. In this context, unmarried people have a lesser availability of family support and social networks, poorer health habits (smoking, alcohol abuse, sedentary lifestyle), and less motivation to follow therapeutic recommendations.

The greater relative inequality observed in women suggests that they have been the most severely affected subjects in terms of the availability of care, access to treatments, and therapeutic and dietetic monitoring, particularly in the context of a low educational level. The lesser relative inequalities seen in men could reflect (particularly in the case of married individuals) greater care received and fundamentally provided by women, whether spouse or female siblings and/or other female relatives, at all educational levels. In Spain, the responsibility of providing care for the ill falls largely on women,20 particularly those with a lower educational level, unemployed women, and women belonging to less privileged social classes.21 Despite changes in younger Spanish female cohorts, which tend to balance the genders in terms of educational level and professional occupation, the gender distribution regarding the provision of care for the ill still lags behind the situation found elsewhere in Europe. In effect, Spanish women remain the main providers of care centered on the family.22 Although from the age of 65 years onwards dependency exhibits a clear female character (two-thirds of all dependent people being women), the corresponding caregivers are also women, and in the case of married dependent persons, the woman usually takes care of the man (in 41.2% of the cases), rather than the other way around (15.3%).22

Among married couples, the wife is usually the person responsible for exerting a positive influence on the spouse regarding healthy living. This is particularly the case in adherence to dietetic instructions,23 obliging the woman to take on physical and emotional burdens that can negatively affect her own health.24,25 The negative effect of widowhood upon mortality (less social support, a greater frequency of dependency, depression, loneliness and lower incomes) is compacted by the social inequality in mortality (with higher mortality among lower educational levels). In this regard women, who are more often widowed and have a poorer social position, find themselves in a situation of greater relative inequality.26,27

On the other hand, and in contrast to women, men die more frequently while they are married. This implies that they can receive care from the spouse for a longer period of time than women, and therefore have greater protection against DM mortality—particularly men with a high educational level—and hence longer life expectancy. In men, the loss of the spouse represents the loss of their main source of social support, and this loss is more serious when their educational level is low.26

Although in absolute terms the impact of widowhood on men is greater than on women, in relative terms single and separated or divorced males are the individuals that show the greatest social gradients—possibly as a consequence of their disadvantage with respect to married men in terms of available family and social support, with an unhealthy lifestyle and with less motivation to adhere to treatment. In Spain it has been seen that separated or divorced men are at a greater risk of suffering chronic depression than other males, while separated or divorced women are more likely to suffer both chronic anxiety and chronic depression.28

LimitationsDespite the fact that we made use of a longitudinal database, the study has some limitations inherent in its cross-sectional design, which makes it difficult to establish causal relationships. For example, marital status designated in the BDLPA corresponds to that existing on the census date (2001), without taking into account possible transitions that may have taken place before that date or up until the date of death, and their possible effects upon mortality risk. Those studies based on longitudinal perspectives have shown for example that remarrying after a failed marriage exerts a protective effect against mortality.29 The great transformations seen in recent decades in the demographic structure of families in Spain, such as older age at the time of first marriage, and a greater frequency of divorce, monoparental families or de facto unions, among other circumstances,30 give us an opportunity to explore how these changes can modify the picture regarding the relationship between marital status and mortality, as well as their effect upon social inequality.

Implications for public health and the diabetic patient care servicesThe study of social inequalities in DM mortality has mainly been conducted from two major perspectives. On one hand, analyses have been made of individual social position,3 expressed in terms of educational level, social class or income level, and on the other hand defined contextual analyses have been carried out according to the deprivation level of the restricted area of residence of the deceased individuals.4 The inclusion of marital status adds a new analytical dimension that refers us to the family context, the home—a context very significant for daily social interaction. This setting is crucial to the care family members provide to each other, and is therefore relevant for the control of a disease such as DM.31 The family environment should also be more generally recognized as a conditioner of health in the sense that it constitutes a fundamental social context for health education, which is a key determinant of health,32 being strongly associated with DM morbidity–mortality. However, the current strategies of the health services regarding the primary or secondary prevention of DM, focused on modifying individual lifestyles, focus very little attention on the effect of socioeconomic variables, social support or the family situation of the patients.33 Although interventions that take these factors into consideration have been very limited in the context of DM, the results of a program specifically targeted toward people of low socioeconomic level have recently been published. This program took the social and family context into account, and revealed an improvement in behavior related to the self-care of patients with socioeconomic deprivation.34

ConclusionsIn both genders educational level is a key determinant of mortality due to DM in Andalusia, and its relevance is comparatively greater in women. In men, marital status is also a key factor.

In order to address the inequalities in mortality, our results suggest that the current emphasis on individual factors and self-care should give way to interventions targeted on the family, the community and the other social contexts closest to the patients.

Financial supportThis study was supported by a research grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Carlos III Health Institute (Ref. PI 15/01106).

AuthorshipAEP and JACD designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, prepared the first draft of the manuscript, carried out a critical review of the contents, and approved the definitive version of the article.

IGJ, GJR, VSS, EMS and MAD made critical contributions to the contents, and all the authors approved the final version of the study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to the contents of the manuscript.

Thanks are due to the Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía, particularly to Dr. Francisco Viciana, and to the team in charge of the creation and development of the Base de Datos Longitudinal de Población de Andalucía (BDLPA). Thanks are also due to the Integral Diabetes Plan of Andalusia (Plan Integral de Diabetes de Andalucía).

Please cite this article as: Escolar-Pujolar A, Córdoba Doña JA, Goicolea Julían I, Rodríguez GJ, Santos Sánchez V, Mayoral Sánchez E, et al. El efecto del estado civil sobre las desigualdades sociales y de género en la mortalidad por diabetes mellitus en Andalucía. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:21–29.