Not all individuals referred to gender identity units receive gender-affirming medical treatment (GAMT). However, there is a paucity of literature examining the reasons for this. This study aimed to investigate the reasons for not initiating GAMT in individuals who initially reported gender identity concerns and requested body changes in a gender identity unit in Spain, all of whom underwent psychological assessment and counseling.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed a total of 457 health histories and collected basic socio-demographic data and information on reasons for not initiating GAMT. This information was grouped into categories based on thematic similarity following consensus among the authors.

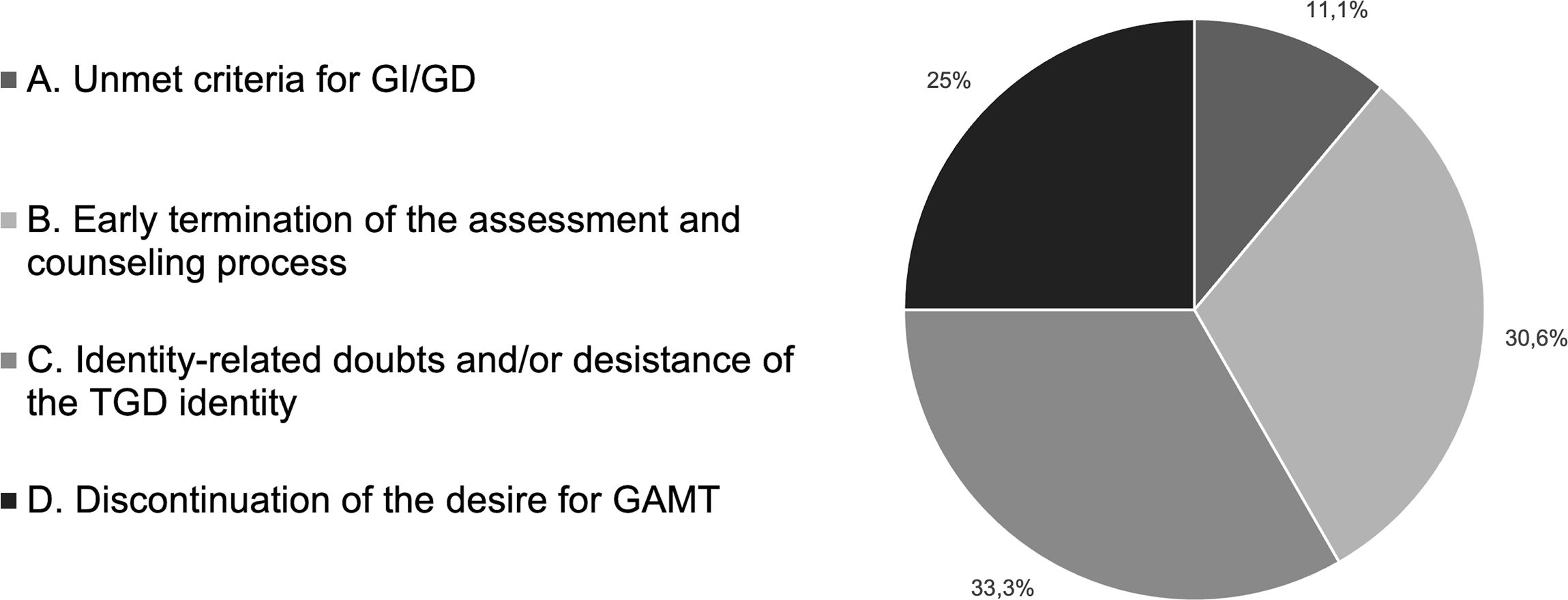

ResultsWe identified a total of 62 patients who did not start GAMT. A total of 26 were deemed ineligible for issues related to mental health, identity development, and inadequate understanding of the GAMT protocol. The remaining 36 patients were counseled and followed up for a mean of 8.4 months. We categorized the reasons for not starting GAMT into 4 groups: (A) failure to meet criteria for gender incongruence/dysphoria (four patients); (B) premature termination of the assessment/counseling process (11 patients); (C) gender identity-related doubts and/or desistance of the transgender identity (12 patients); and (D) discontinued desire for GAMT (9 patients).

ConclusionsGAMT is not the endpoint for all individuals seeking care, and reasons for not starting GAMT are heterogeneous and sometimes complex. Psychological assessment and counseling remain important features of quality gender-affirming care, and current debates about access to GAMT should take these experiences into account to better inform its future provision.

No todas las personas atendidas en unidades de identidad de género reciben tratamiento médico de afirmación de género (TMAG). Sin embargo, son escasas las publicaciones que analicen las causas. El objetivo de este estudio fue investigar las razones por las que no se inició el TMAG en personas que inicialmente refirieron problemas de identidad de género y solicitaron modificaciones corporales en una unidad de identidad de género de España, todas las cuales recibieron evaluación y acompañamiento psicológico.

Material y métodosSe realizó un análisis retrospectivo de 457 historias clínicas y se extrajeron datos sociodemográficos básicos e información sobre los motivos para no iniciar el TMAG. Esta información se agrupó en categorías temáticas basadas en el consenso entre los autores.

ResultadosSe identificaron 62 pacientes que no iniciaron el TMAG. Veintiséis fueron considerados inelegibles por cuestiones de salud mental, desarrollo identitario y comprensión inadecuada del protocolo de TMAG. Los 36 pacientes restantes recibieron acompañamiento psicológico y seguimiento durante una media de 8,4meses. Las razones para no iniciar el TMAG fueron agrupadas en cuatro categorías: (A) incumplimiento de criterios de incongruencia/disforia de género (4 pacientes); (B) interrupción prematura del proceso de evaluación/acompañamiento (11 pacientes); (C) dudas identitarias y/o desistencia de la identidad transgénero (12 pacientes); y (D) descontinuación del deseo de recibir TMAG (9 pacientes).

ConclusionesEl TMAG no es el punto final para todas las personas que buscan asistencia, y las razones para no iniciar el TMAG son heterogéneas y a veces complejas. La evaluación y el acompañamiento psicológico siguen siendo elementos importantes de una atención afirmativa de género de calidad, y los debates actuales sobre el acceso al TMAG deberían tener en cuenta estas experiencias para mejorar su prestación en el futuro.

This study describes the reasons for not initiating gender-affirming medical treatment (GAMT) in 62 patients who underwent psychological assessment in a gender identity unit. A total of 26 patients were deemed ineligible due to issues related to mental health, identity development, and inadequate understanding of the GAMT protocol. Four of the remaining 36 did not meet the criteria for gender incongruence/dysphoria, 11 terminated the assessment/counseling process prematurely, 12 experienced doubts or desisted from a transgender identity, and 9 expressed a discontinued desire for GAMT.

IntroductionThe number of individuals referred to specialized gender services (hereafter gender identity units or GIUs) has increased significantly over the past decade in Western countries, particularly among adolescents assigned female at birth.1 Some of these individuals experience a mismatch between their gender identity and their sex assigned at birth, referred to as gender incongruence (GI).2 This can lead to significant distress, clinically termed as gender dysphoria (GD),3 which they may seek to alleviate through gender-affirming social and/or medical interventions. The former may include changes in name, pronouns, and gender presentation—commonly known as social transition—while the latter may include the suppression of puberty through gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, hormone therapy with testosterone or estrogen, and various types of genital (e.g., vaginoplasty) and non-genital (e.g., chest masculinization) surgery aimed at modifying the person's physical sex characteristics—commonly known as medical transition.

The literature on the psychosocial benefits of both social and medical gender transition is mixed and conflicting. Among transgender and gender diverse (TGD) children and adolescents, social gender transition has been associated with reduced levels of mental health problems, comparable to those of normative control samples of peers or siblings,4,5 while other studies have failed to find an association between social transition and mental health status.6,7 Similarly, medical transition has been found to be associated with significant improvements in several domains of psychosocial functioning,8,9 while other studies have reported persistent or even increased psychiatric needs after medical transition.10,11 This, along with the lack of a strong evidence base supporting GAMT according to recent systematic reviews,12,13 has led to important debates and disagreements among clinicians, researchers, and policymakers, particularly regarding approaches to treating minors, who represent the fastest growing population of gender-affirming care seekers worldwide.14 This situation reflects some of the pressing moral and ethical dilemmas faced by health care professionals in the field of gender-affirming care.15

While the debate is still going, most studies published in the literature focus on people referred to GIUs who seek, start, and continue with GAMT. However, not all patients follow this trajectory, including those for whom GAMT is the recommended pathway following an initial psychological assessment or counseling. For example, in a study of 1072 adolescents consecutively referred to the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria in Amsterdam (The Netherlands) from 2000 to 2016,16 the authors found that an average of 22.3% of those diagnosed with a form of GD, and therefore considered eligible, did not initiate GAMT with puberty suppressants and/or hormone therapy during the study period. The authors also reported that most of the 107 adolescents who ended the diagnostic assessment process prematurely—and thus remained undiagnosed—did so because they no longer wanted GAMT.16 In a subsequent analysis of 1681 children and adolescents assessed at the same GIU between 1972 and 2018,17 the authors reported that 37% of those potentially eligible for GAMT did not start GAMT for not meeting criteria for a GI/GD diagnosis, not returning to the GIU despite becoming eligible for GAMT, discontinuation of the diagnostic assessment, and reasons related to mental health issues or incompetence to give informed consent, medical conditions, or the GIU protocol for starting GAMT. A different study of 75 adolescents and young adults referred to the Hamburg Gender Identity Service from 2013 to 2017 revealed,18 at the 2-year follow-up, that 9 participants who had not yet received GAMT discontinued or ended transition-related care at the service for a variety of reasons, mainly related to mental health issues and long travel distances. Recent studies from English19 and Australian20 pediatric services reported that 2.9% up to 4.9% of young people were discharged or had a referral closure before starting GAMT because they no longer identified as TGD,19 a phenomenon known as desistance.

Despite these studies, there is a paucity of data on individuals who are assessed and/or counseled and monitored but do not start any type of GAMT. Therefore, the main objective of the current study is to fill this gap by describing the main reasons for not starting GAMT among individuals attending a GIU in Spain, all of whom initially reported gender identity concerns and requested body changes, some of whom were considered eligible for GAMT after an initial psychological assessment and counseling phase.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective chart review of individuals who underwent psychological assessment and counseling at the GIU of Dr. Peset University Hospital (Valencia, Spain). This GIU acts as a reference service for residents of the Valencian Community and includes a multidisciplinary team of psychologists, pediatricians, endocrinologists, gynecologists, surgeons, and assisted reproduction experts. New referrals come from primary or specialized care providers, LGBTQ+ associations, or direct requests. However, in accordance with the team-agreed care protocol, all must undergo an initial psychological assessment and counseling (health care level 1) by a clinical psychologist with relevant expertise in sexology prior to their referral to the endocrinology service (health care level 2).

This assessment and counseling phase focuses on 2 main aspects. First, determine whether the person meets the criteria for GI/GD and rule out the possibility of significant psychopathology or mental health problems (e.g., borderline or psychotic disorders) that may influence the person's desire to seek GAMT or destabilize their future identity development. Second, understand the person's psychosocial and family background, gender history, and reasons for seeking GAMT. Third, explain important aspects associated with the possibility of starting GAMT, including its known and unknown consequences or undesired effects (e.g., loss of fertility) and its limitations to avoid unrealistic expectations and future frustration. Finally, offer alternative pathways to GAMT to live and express a TGD identity. In addition, to start GAMT, the person must have no physical contraindications and a stable personal situation, which excludes behavioral problems that may lead to treatment noncompliance. All information is provided in writing and verbally and is individualized to the cultural level of each person to ensure adequate understanding.

The length of the assessment is variable (usually between 1 and 2 months), with as many sessions as needed to allow the person to reflect calmly on all the information given and on their decision on whether to start GAMT. In this regard, respect for patient autonomy and shared decision-making are key elements of the process, as emphasized in the 8th edition of the Standards of Care (SOC 8) published by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH).21 However, for individuals who have doubts about their identity, their desire to start GAMT, or any other circumstances that may require psychological support, the counseling and follow-up time in health care level 1 can be extended for longer periods of time as needed to ensure appropriate informed consent. Once the assessment is complete, individuals who wish to start GAMT are referred to the endocrinology service, where all information is again provided by the endocrinologist. GAMT is covered by the Spanish public health system.

This study focuses on individuals potentially eligible for GAMT who were counseled and followed up at health care level 1 but not ultimately referred to the endocrinology service, and individuals who were eligible and referred to the endocrinology service to start GAMT after the initial psychological assessment, but later expressed no desire for GAMT. Specifically, we aimed to identify and understand the reasons why they themselves, or together with the team, decided to stop seeking GAMT. In addition, we also describe those patients who were considered ineligible for GAMT at the time of initial psychological assessment. Remarkably, all these patients’ initial requests included a desire for body changes due to concerns about their gender identity. To do this, we retrospectively searched the clinical histories of individuals assessed and counseled at health care level 1 and collected information on their age at first visit, sex assigned at birth, social transition status, and follow-up. These data were analyzed descriptively using means, medians, and percentages. Information on participants’ reasons for not starting GAMT was categorized according to their thematic similarity following consensus among the authors. If more than one reason was present, the most prominent reason was prioritized. Information on the participants’ reasons for not being considered eligible for GAMT at health care level 1 was analyzed descriptively using percentages. According to the although hospital ethics committee, ethical approval was deemed unnecessary for this study due to its retrospective design and absence of intervention, all patients assessed at the index visit gave their prior written informed consent for their anonymized data to be included in research studies.

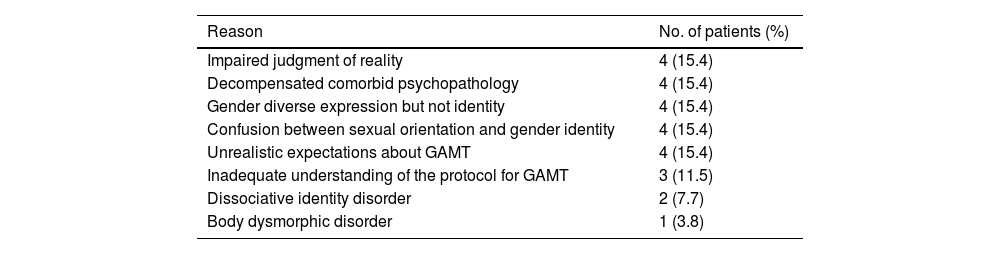

ResultsWe reviewed a total of 457 health histories and identified 62 patients who did not start GAMT. A total of 26 out of these patients were considered ineligible for GAMT at the initial psychological assessment for a variety of reasons, including issues related to mental health, gender expression and sexual identity development, and inadequate understanding the GAMT protocol (Table 1).

Reasons for not being considered eligible for GAMT.

| Reason | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Impaired judgment of reality | 4 (15.4) |

| Decompensated comorbid psychopathology | 4 (15.4) |

| Gender diverse expression but not identity | 4 (15.4) |

| Confusion between sexual orientation and gender identity | 4 (15.4) |

| Unrealistic expectations about GAMT | 4 (15.4) |

| Inadequate understanding of the protocol for GAMT | 3 (11.5) |

| Dissociative identity disorder | 2 (7.7) |

| Body dysmorphic disorder | 1 (3.8) |

Note. GAMT: gender-affirming medical treatment.

The remaining 36 potentially eligible participants were counseled and monitored for a mean of 8.4 (SD=8.8) months (Mdn=5 months, range 0–37). Twenty-one participants (58.3%) were assigned male at birth and 15 (41.7%) female at birth, and the mean age at the index visit was 18.9 (SD=9.7) years (Mdn=16 years, range 4–44). At the time of assessment, 69.4% were minors (4–17 years old) and 38.9% had already fully socially transitioned in both their private and public lives. After reviewing their past medical histories, we decided to categorize the reasons for not starting GAMT into the following four groups: (A) unmet criteria for GI/GD; (B) early termination of the assessment and counseling process; (C) identity-related doubts and/or desistance of the TGD identity; and (D) discontinuation of the desire for GAMT (Fig. 1). Below, we briefly describe the casuistry of the patients included in each of these categories.

- A.

Unmet criteria for GI/GD

Four of the 36 patients (11.1%) were not referred to the endocrinology service for GAMT because they did not clearly meet the required criteria for a diagnosis of GI/GD. None of these patients had socially transitioned nor clearly or consistently articulated or expressed a gender identity that differed from their assigned sex at birth (i.e., a TGD identity). In fact, one of them expressed no dysphoria about their primary and/or secondary sexual characteristics. As a result, it was considered that their gender-related issues were part of their broader identity development and therefore should not be subject to any form of GAMT.

- B.

Early termination of the assessment and counseling process

Another 11 patients (30.6%) were not referred to the endocrinology service because the assessment and counseling process was terminated prematurely. Of note, their request for GAMT was inconsistent and fluctuated over time. None of these patients, except for one, had socially transitioned at the index visit. Four of the patients and their families decided to stop the gender transition process themselves, 2 of whom had previously expressed doubts and uncertainty about their gender identity and/or sexual orientation. Six patients were lost to follow-up because they stopped attending or canceled appointments. The remaining patient, the only one who had socially transitioned, tragically committed suicide during the counseling and follow-up period. This patient had a history of severe mental health and family issues that were not directly related to the gender transition process, and was also being treated and followed by the hospital psychiatric service.

- C.

Identity-related doubts and/or desistance of the TGD identity

Twelve out of the 36 patients (33.3%) expressed significant doubts about their gender identity or explicitly desisted from their previously expressed TGD identity during the counseling and follow-up period and prior to the referral to the endocrinology service, that is, they questioned their TGD identity and/or returned to identifying with their sex assigned at birth (i.e., they stopped identifying as TGD). Five of them had already socially transitioned at the index visit. As a result, medical gender transition was no longer the desired pathway and the request for GAMT was ultimately withdrawn.

- D.

Discontinuation of the desire for GAMT

The remaining 9 of the 36 patients (25%), 7 of whom had already socially transitioned at the index visit, were eligible for GAMT and referred to the endocrinology service at the end of the assessment process but decided not to proceed with GAMT. However, all of them continued to identify as TGD. One expressed doubts and experienced fluctuations in gender identity, after which they decided against GAMT because they had learned to accept their body as it was, despite their TGD identity. Seven patients refrained from GAMT due to fear and/or concern about the physical and psychological effects of the hormonal interventions involved in GAMT (1 because the participant did not want to follow the GAMT protocol after learning that it would come into conflict with some of the participant's current lifestyle choices).

DiscussionThe aim of this study was to describe the reasons for not starting GAMT in a sample of individuals from health care level 1 of a GIU in Spain, consisting of psychological assessment, counseling, and follow-up. After reviewing a total of 457 past medical histories, we found 62 individuals who did not start GAMT. All of them reported gender identity concerns and requested body change interventions at the index visit. Twenty-six were considered ineligible for GAMT at the time of psychological assessment due to issues related to mental health, identity development, and inadequate understanding of the GAMT protocol, while the remaining 36 potentially eligible participants were counseled and followed up for a mean of 8.4 months. Four patients were not referred to the endocrinology service because they did not clearly meet the criteria for GI/GD, while in 11 cases, the assessment process was terminated prematurely, either at the request of the patient or due to failure to attend appointments. Tragically, one of these patients committed suicide, although the causes did not seem to be directly related to the gender transition process, as this patient had a long history of severe mental health and family issues. Twelve of the remaining patients experienced identity-related doubts and/or desisted from their prior TGD identity and therefore withdrew their request for GAMT, while 9 eligible participants expressed a discontinued desire to start GAMT, mainly due to fears or concerns about its potential physical and/or mental health implications. In essence, our findings show that some individuals who present to the GIU and undergo psychological assessment, counseling, and follow-up do not start GAMT, even when they experience GI/GD and express a desire to change their physical appearance through medical procedures. These findings are consistent with former studies16–20 showing that psychological concerns, not meeting the diagnostic criteria for GI/GD, cessation of the psychological assessment process, discontinuation of the desire for GAMT, and desistance from a TGD identity stand out as reasons for not initiating GAMT.

These findings have four implications. First, they reveal that the psychological assessment and counseling phase is valuable in identifying those individuals for whom GAMT may not be the most beneficial way forward because their current mental health status, stage of identity development, or ability to understand what GAMT entails and offers does not allow for the full exercise of autonomy and informed consent. Therefore, it is necessary to explore whether there are unrecognized mental health problems or other concerns or difficulties, not directly related to gender, that may be influencing the person's feelings of GI/GD or their desire to seek GAMT, as these will not be resolved or may even be exacerbated by GAMT. The aim of psychological assessments is therefore not to create more barriers to gender-affirming care, but to support the patients’ autonomy, decision-making, and informed consent through a deeper understanding of themselves and of the circumstances that may be influencing their gender-related distress,22 which are key features of quality gender-affirming care. Given the ethical dilemmas surrounding gender-affirming care and the divided opinions on the evidence for GAMT, it is crucial to proceed with caution to maximize long-term health benefits and minimize the risk of iatrogenic harm.

Secondly, it is important to emphasize that GAMT is not necessarily the ultimate goal of gender-affirming care. Rather, GAMT should be seen as part of an ongoing process of exploration, reflection, and shared decision-making that revolves around and changes according to each person's developmental context and broader process of identity elaboration and expression. In this regard, our findings suggest that referred patients’ requests for GAMT may sometimes be better understood as signs of their unique process of self-exploration and self-understanding, and that this may not be stable, but change over time. Some patients may be adamant about their identity and treatment desires at referral, but later change their minds as the assessment progresses. In other cases, young patients who initially request GAMT may simply need psychological counseling and support to clarify their gender identity or sexual orientation, as these are sometimes confused. Importantly, individuals need to be offered alternatives to GAMT so that they can freely and fully express and live their TGD identities, thereby challenging deeply held transnormative ideas about how TGD people should think about themselves and relate to GAMT.23 In our view, psychoeducation, counseling, and support can be highly beneficial for some gender-distressed individuals, whereas highly medicalized services risk overlooking their needs. In this regard, the phase of psychological assessment and counseling should be conceptualized as an opportunity to support each person in their gender exploration process, while acknowledging the complexities inherent in their care, which include developmental, psychosocial, and familial factors.24 Indeed, when working with minors, the SOC 8 recommends undertaking a comprehensive psychological assessment from a neutral and curious clinical stance that does not favor any particular outcome or identity,21 based on evidence of the benefits of GAMT that comes from GIUs with such assessments.9

Thirdly, our findings show that gender identity can be fluid and not necessarily remain stable over time, which is consistent with research showing that a proportion of young people experience gender identity fluidity, both within and between TGD and cisgender identities.25 The findings also show that some TGD people's desires for GAMT can change and shift, and that this may not be an uncommon phenomenon, as recent reports have shown.26 Furthermore, the confusion between gender identity and sexual orientation observed in some young patients may suggest that, sometimes, gender diverse expression or identity can evolve into a non-heterosexual sexual orientation rather than a TGD identity, which is consistent with the findings from longitudinal reports.27 In light of this evidence, we believe that there should be sufficient space and time for exploration and reflection on sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender-related treatment desires of young people before accessing GAMT. Otherwise, some individuals may end up accessing medical interventions that feel affirming at the time, but harmful or distressing at a later point in their lives.28 The affirmation of TGD people's unique needs and experiences, based on respect for their autonomy and shared decision-making, should not lead to a rushed process of accessing GAMT, but rather open up a space to facilitate their own identity exploration and expression in a supportive and collaborative way, avoiding preconceived ideas of what the outcome should be. This does not mean, however, that access to GAMT should be delayed unjustifiably or unnecessarily when clearly indicated, such as when the individual is in severe distress.

Finally, we would like to highlight the role that multidisciplinary teams of professionals with expertise in the treatment GI/GD can play in improving the quality of gender-affirming care. Essentially, these teams provide a wider space for exploration and reflection on gender identity, as well as more opportunities for discussion of GAMT and shared decision-making between patients and health care professionals. In addition, bringing clinical insights from different disciplines into the process of gender transition can broaden the perspectives of both health care professionals and patients involved, leading to better decisions and outcomes in the long term. Therefore, we believe that isolated points of direct access to GAMT without any kind of psychological assessment and counseling29 may be detrimental to the wellbeing of some young people, as they would greatly benefit from exploring and clarifying their identities and gender-related treatment desires before accessing the partially or totally irreversible interventions involved in GAMT. Leaving the decision to provide GAMT to endocrinologists without the input of mental health professionals, thus creating a dilemma between acting without questioning or being perceived as pathologizing, is a threat to quality gender-affirming care.

However, there are some limitations associated with the study. Firstly, of note, the number of clinical histories we reviewed does not include the full sample of individuals who have been assessed and treated at the GIU, whose demographic characteristics have been reported elsewhere.30 Secondly, the study sample comes from a single GIU and may not be representative of the wider population of people who seek GAMT, let alone of the subpopulation of individuals who do not start GAMT. Finally, although this GIU is the reference service for residents of the Valencian Community, we cannot exclude the possibility that some participants who dropped out of the psychological assessment and counseling process, or who were deemed ineligible for GAMT, sought it in another province or region. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results.

ConclusionsIn this study, we describe the reasons for not starting GAMT in a sample of individuals who reported gender identity concerns and requested body changes in a gender identity unit in Spain. In accordance with the team-agreed care protocol, all underwent psychological assessment, counseling, and follow-up for a variable period of time. A proportion of patients were considered ineligible for GAMT due to issues related to mental health, identity development, and inadequate understanding of the GAMT protocol. Among the remaining potentially eligible patients, the main reasons for not initiating GAMT were not meeting the criteria for GI/GD, premature termination of the assessment and counseling process, experiencing identity-related doubts and/or desisting from the TGD identity, and no longer wishing to go on with GAMT due to health and protocol compliance concerns. The findings highlight the importance of psychological assessment and counseling as tools for quality care through the exploration of gender identity, sexual orientation, and gender-related treatment desires; the fluid nature of gender identity for some young people; and the role that multidisciplinary teams can play in improving the quality of gender-affirming care. In conclusion, the findings of this study are valuable in that they provide further understanding of individuals who present to the GIU but have different care trajectories, which is essential for the development of tailored services to meet their needs. However, given the paucity of literature, more research is needed to understand the experiences and needs of individuals who seek but do not move into GAMT.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.