The detection of an adrenal gland neoplasm in the study of arterial hypertension (AHT) opens up a wide range of diagnostic possibilities, potentially as a cause of or independent from AHT itself. We report a case with this association, with a peculiar diagnostic trajectory and an exceptional final diagnosis.

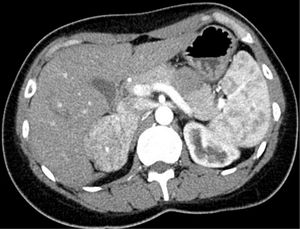

A 29-year-old woman was referred to the nephrology clinic after the detection of AHT due to headaches starting one year ago. She had undergone surgery at 5 years of age due to left pyeloureteral stenosis, and reported recent pollakiuria with nocturia. She provided a primary care report with mean daytime and nocturnal blood pressure (BP) values of 154/100 and 140/90mmHg, respectively. The laboratory tests requested by her primary care physician revealed low serum potassium levels in two determinations (3.49 and 3.12mEq/l), with normal renal function. The expanded study in the Nephrology Department revealed low plasma renin activity (0.2ng/ml/h) with normal-low aldosterone levels (7.3ng/dl), normal urinary catecholamines and a CT angiographic scan evidencing a hypervascular right adrenal mass measuring 6cm in diameter (Fig. 1). After consulting the Endocrinology Department, the study was further expanded with fractionated urinary metanephrines, urinary 3-methoxytyramine and urinary free cortisol – all of them yielding normal values – in addition to ACTH (34.5pg/ml) and plasma dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (1.31μg/ml), as well as serum chromogranin A and testosterone – all of which proved normal. Upon assessment in the clinic with these results, the patient presented no menstrual disorders or hirsutism, denied regular intake of liquorice, and had a normal phenotype. Preferential surgery was indicated in view of the size of the tumor, and the serum samples stored in the hospital serum repository were used for simultaneous measurement of intermediate metabolites of steroidogenesis in the core laboratory. Surgery took place one week later via subcostal laparotomy due to the potential malignancy of the lesion. The right adrenal gland was removed, weighing 87.1g and containing a 6.5cm homogeneous, solid non-encapsulated tumor with a thin, compressed adrenal tissue component. The pathology study revealed tumor growth with a trabecular and tubular-pseudoglandular pattern, with no mitoses, necrosis, calcification or vascular invasion. Immunohistochemistry proved positive for melan-A, inhibin and CKA1-AE3, and negative for chromogranin, S100, CEA, EMA and renal cell marker. All these data were consistent with adrenal gland adenoma, with Ki67<2%. The results of the pending tests were received after the operation, revealing deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) levels almost 16 times above the upper limit of normal (ULN) (237.9ng/dl; ULN: 15), with normal 11-deoxycortisol and corticosterone concentrations. Evaluation after 15 days showed BP to have normalized, the polyuria had disappeared, and the serum potassium concentration was normal (4.32mEq/l). One month after surgery, serum testing showed normal DOCA values (7.1ng/ml), with still low renin activity levels. Two and a half years after surgery, the patient remains asymptomatic, with normal PA and no surgical site lesions in the abdominal MRI study.

The possibility of a secondary form of AHT should be considered in the presence of certain clinical symptoms, mainly headache, tachycardia or excessive perspiration suggesting catecholamine excess, or laboratory changes – particularly spontaneous hypopotassemia.1 Such electrolyte alterations, in the absence of gastrointestinal losses or iatrogenic losses due to the use of diuretics, suggest possible mineralocorticoid excess. The most common underlying cause in this context is primary aldosteronism,2 characterized by autonomous aldosterone secretion in a unilateral adenoma or secretion by both glands in the case of bilateral hyperplasia. The other variants, including unilateral hyperplasia, multiple adenomas, aldosterone-producing carcinomas (isolated or co-secreted with other steroids) and genetic forms, are much less common. In all these presentations, renin (activity or mass measurement) is low or suppressed, with normal or high aldosterone levels (usually >15ng/dl), not suppressible with saline overload. Another form of apparent mineralocorticoid excess occurs with severe hypercortisolism due to overwhelming of the glucocorticoid receptors and escape from inactivation by 11ß-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11ß-HSD2), usually associated with malignant ectopic ACTH production and without a Cushing phenotype because of the explosiveness of the course of the disorder.3 Excessive liquorice intake, through blockade of the same inactivating enzyme, causes cortisol at physiological concentrations to activate the mineralocorticoid receptor, with consequent renin suppression, saline retention, and excessive urinary potassium excretion.4 This same genetic-based mechanism underlies the so-called apparent mineralocorticoid excess syndrome due to heterozygous 11ß-HSD2 enzyme mutations.5 Non-tumoral excess of other precursors of steroidogenesis as a cause of mineralocorticoid excess can be found in pediatric patients, associated to congenital enzyme deficiencies, particularly 11ß-hydroxylase,6 with an excess of 11-deoxycortisol and DOCA (both exerting a mineralocorticoid effects), and in defects in androgen synthesis (17α-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase) – with associated gonadal alterations.7 An excess of precursors of steroidogenesis associated to neoplastic conditions without Cushing syndrome is exceptional, and is dependent upon the level and intensity of enzyme blockade within the tumor tissue. This can be evaluated by chromatography, showing the secretion profile of each tumor. The condition is usually associated to adrenal gland carcinomas,8 and exceptionally to adrenal adenomas – unilateral (as in our case)9 or bilateral.10 Our patient had a number of very unusual characteristics, particularly the surprising detection of an adrenal tumor with isolated DOCA production, and especially the fact that this was a benign neoplasm despite its size and radiological appearance. The difference between an adrenal adenoma and carcinoma depends on not entirely precise criteria before surgery; careful surgical dissection in cases with potential malignancy is therefore crucial. Clinical, biochemical and radiological reversal after surgery confirmed the tumor origin of DOCA, with no other elevated steroidogenic metabolite, indicative of selective production of this hormone within an adenoma that appeared radiologically aggressive in view of its size and vascularization.

In conclusion, a new case of adrenal tumor producing DOCA has been described, with the peculiarity of its benign nature, favorable course and the absence of hypersecretion of other steroid metabolites.

AuthorshipMiguel Paja: study conception and design, and writing of the manuscript. Adela L. Martínez: data collection and interpretation. Andoni Monzón: data collection and interpretation. Javier Espiga: patient care and clinical monitoring, and critical review of the article.

Thanks are due to the patient for her collaboration in this publication.

Please cite this article as: Paja-Fano M, Martínez-Martínez A-L, Monzón-Mendiolea A, Espiga-Alzola J. Una causa singular de hipertensión endocrina. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2020;67:683–685.