In late 2015, the ex-President of the United States, Jimmy Carter, announced that the brain metastases of his melanoma had disappeared completely thanks to a drug called pembrolizumab. Different media spoke of the “miraculous” recovery of the Nobel Prize winner. Treatment with monoclonal antibodies targeted to specific molecules of the immune system, or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICPIs), constitutes one of the great future promises in the management of different diseases, particularly cancer. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first drug belonging to this new family (ipilimumab) in 2011, for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Over the following months pembrolizumab and nivolumab were also approved for the same disease. Both of these drugs were in turn authorized shortly afterwards for the treatment of lung and kidney cancer. To date, 6 drugs have been approved as treatment for different neoplastic diseases: atezolizumab, avelumab and durvalumab, in addition to the three drugs mentioned above.1

A change in strategyUnlike classical chemotherapy, which acts directly upon the tumor cells, ICPIs stimulate the T lymphocytes of the immune system to eliminate the malignant cells. The activation of the T lymphocytes requires a double signal.2 On one hand, interaction is required between the T cell receptor and a peptide of the antigen-presenting cell (APC) forming part of the major histocompatibility complex. Furthermore, interaction is required between a second T lymphocyte receptor and its specific ligand of the APC. In turn, activation of the immune cell is accompanied by the induction of inhibitory receptors with the purpose of avoiding autoimmune phenomena and minimizing tissue damage during disproportionate activation of the immune response.3 These receptors, known as immune system checkpoints, fundamentally act by blocking the second activating signal. Many studies over the last few decades have identified different molecules with this function, such as CTLA-4, PD-1 and its two natural ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2), Tim-3 and LAG.3 It has been known for years that these checkpoints are over-expressed in intratumor lymphocytes, basically due to T cell exhaustion as a result of the chronically maintained stimulus against the tumor. Furthermore, certain cancers enhance checkpoint expression with the aim of evading immune vigilance. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are monoclonal antibodies that block these repressor molecules, thereby magnifying the potential of the cytotoxic T lymphocytes. At present, the approved drugs inhibit two of these checkpoints and comprise the anti-CTLA4 agents (ipilimumab) and drugs that act upon PD-1 (pembrolizumab and nivolumab) or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab and durvalumab). Many other inhibitors are also being analyzed in different clinical trials.

Different side effectsBased on the mechanism of action involved, it can be deduced that the side effects of the ICPIs are related to immune system over-activation, with the possible involvement of practically all the body organs and systems (skin, gastrointestinal system, liver, nervous system, lungs, etc.). Over 90% of all the treated patients experience immune-related adverse effects, with grade 3–4 toxicity in 10–20% of the cases.4 As a common element, the clinical expression is the development of organ-specific autoimmune disease in all cases. Within this range of side effects, endocrine gland autoimmunity is the second most common manifestation after skin effects. The hypophysis and thyroid are the most frequently implicated glands in this respect.5 Hypophysitis is the most characteristic adverse effect of the anti-CTLA-4 drugs, especially ipilimumab, with a reported incidence of 0–17%.6 Nevertheless, the most common endocrine manifestations appear in the thyroid gland, with incidences of up to 9–10% according to most published series.7 While the clinical behavior of hypophysitis is similar to that of lymphocytic hypophysitis, the thyroid gland manifestations are similar to those of silent thyroiditis, with an initial phase (not always present) characterized by hypothyroidism, followed in practically all patients by hypothyroidism. There have also been less frequent reports of autoimmune adrenalitis and type 1 diabetes mellitus.8 Although the clinical profile of the endocrine complications of ICPIs is analogous to that of the autoimmune condition not related to the drug, there are a series of specific features that complicate both the diagnosis and management approach.9 The faster course of the disease, the possible appearance of immune-related adverse effects at any time, the basal condition of the patient, concomitant medication, the evolution of the neoplasm or the presence of other associated autoimmune diseases all complicate both diagnosis and treatment. As a result, while these drugs are not particularly toxic in comparison with other antineoplastic agents, patient management is extraordinarily complex.

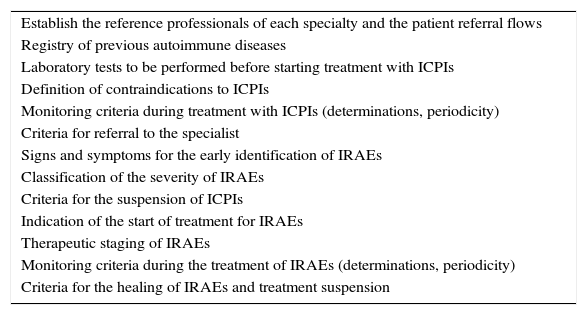

Essential collaborationThe immune-related adverse effects of ICPIs are frequent, can affect practically all the body systems (even simultaneously), are potentially serious, and moreover are very different from the complications that characterize classical chemotherapy. While clinical oncologists have specific knowledge as to how to treat cancer patients, the specialists that treat each of the implicated organs have become familiarized with the concrete management of organ-specific autoimmune diseases. In this respect, collaboration among the different specialties has almost spontaneously been recognized as an absolute necessity in order to minimize the toxicity of these drugs. With the purpose of promoting such collaboration, intervention protocols have started to appear, documenting the interaction among professionals as a key element.1,10–13 One of the first clinical practice guides was published by a group of experts at Gustave Roussy Hospital.10 Their recommendations established 5 fundamental references in the management of immune-related adverse effects: prevention, anticipation, detection, treatment and monitoring. According to the authors, in order to optimize these references, oncologists must receive the support of the specialists as soon as the diagnosis and management of an immune-related adverse effect becomes difficult. In the specific case of our speciality, collaboration between oncologists and endocrinologists is necessary, among other reasons, in order to ensure an early diagnosis and consequent treatment of adrenal gland insufficiency (primary or secondary), which is undoubtedly one of the most serious immune-related adverse effects. Furthermore, the management of hyper- and hypothyroidism, or of diabetes mellitus, is clearly the concern of the endocrinologist. Thus, each center should establish its own protocol, adapted to its specific characteristics. The design of the protocol should involve all the potentially involved specialists (including the specialized nursing staff), and should at least take into consideration each of the aspects detailed in Table 1. Some guides recommend that endocrinologists with experience in immune-related adverse effects should serve as reference professionals and consultants.

Key points to be included in the intervention protocols regarding the adverse effects of ICPIs.

| Establish the reference professionals of each specialty and the patient referral flows |

| Registry of previous autoimmune diseases |

| Laboratory tests to be performed before starting treatment with ICPIs |

| Definition of contraindications to ICPIs |

| Monitoring criteria during treatment with ICPIs (determinations, periodicity) |

| Criteria for referral to the specialist |

| Signs and symptoms for the early identification of IRAEs |

| Classification of the severity of IRAEs |

| Criteria for the suspension of ICPIs |

| Indication of the start of treatment for IRAEs |

| Therapeutic staging of IRAEs |

| Monitoring criteria during the treatment of IRAEs (determinations, periodicity) |

| Criteria for the healing of IRAEs and treatment suspension |

IRAEs: immune-related adverse effects; ICPIs: immune checkpoint inhibitors.

There are still important gaps in our knowledge of the immune-related adverse effects of ICPIs, particularly in the real life setting, since most of the available data come from highly controlled clinical trials. In the immediate future it will be necessary to establish not only the etiopathogenic mechanisms of the immune-related adverse effects, but also their true incidence and severity. Biological markers predictive of both the development of adverse effects and of their possible evolution are lacking. The treatment of such adverse effects is extrapolated from the management strategies that apply to their mirror autoimmune disorders not associated with the use of ICPIs, but it is by no means clear whether this is the best approach. For example, there are doubts as to the utility of TSH in defining the start of treatment with l-thyroxine and as to the required frequency of the control laboratory tests. Furthermore, while the combination of several of these drugs has been shown to be very effective in certain types of cancer, it is not clear whether this practice will increase the incidence or severity of any immune-related adverse effects. The results that are being obtained with ICPIs suggest a rapid expansion of their use and their approval for application in many neoplastic processes. As a result, endocrinological adverse effects can be expected to increase significantly, leading in turn to a growing number of requests for support from endocrinologists that will need to be adequately resolved. Organization within Departments of Endocrinology and close collaboration among medical specialties is the only way to guarantee optimum patient management, where the introduction of ICPIs, capable of healing brain metastatic disease in an ex-President of the United States, has opened a new and promising strategy in the fight against advanced cancer disease.

Please cite this article as: Zafon Llopis C. Inmunoterapia oncológica y endocrinología: una nueva oportunidad para la colaboración multidisciplinar. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2017;64:461–463.