Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a gastrointestinal functional disorder mainly characterised by abdominal pain, bloating and altered bowel habits. Dysbiosis might seem to be involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. Probiotics represent a potential treatment, since these could favour the functional microbiota and improve symptoms. The aim was to review the effectiveness of the use of probiotics in IBS symptomatology, analysing the influence of duration and dose. 18 articles were included. At the individual level, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Bacillus could be useful in the treatment of symptoms. Bifidobacterium bifidum reported the best results (1 × 109 CFU/day for 4 weeks). The most effective combination was 2 Lactobacillus strains, one of Bifidobacterium and one of Streptococcus (4 × 109 CFU/day for 4 weeks). Future clinical trials should confirm these results and analyse the difference between individual and combined treatments.

El síndrome del intestino irritable (SII) es un trastorno gastrointestinal funcional cuya sintomatología incluye dolor e hinchazón abdominal y alteración en el hábito intestinal. Entre los factores causales se encuentra la disbiosis. Los probióticos representan un tratamiento potencial, ya que pueden favorecer la microbiota funcional y mejorar los síntomas. El objetivo fue revisar la efectividad del uso de probióticos en la mejora del SII, analizando la influencia de la duración y la dosis. Se incluyeron 18 artículos. A nivel individual, los géneros Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium y Bacillus podrían ser útiles en el tratamiento de la sintomatología. En concreto, Bifidobacterium bifidum reportó los mejores resultados (1 × 109 CFU/día durante 4 semanas). La combinación más efectiva fue la compuesta por 2 cepas de Lactobacillus, una de Bifidobacterium y una de Streptococcus (4 × 109 CFU/día durante 4 semanas). Futuros ensayos clínicos deberían confirmar estos resultados y analizar las diferencias existentes entre los tratamientos individuales y combinados.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterised by recurrent, chronic abdominal pain, abdominal distension and change in bowel habits.1 The worldwide prevalence is 5–10%2 and it is two to four times more common among females.3 The Rome IV criteria4 are used for diagnosis. IBS is considered when a patient report having had abdominal pain for at least six months prior to diagnosis, occurring for a minimum of one day/week in the last three months. It should be associated with at least two of the following: defaecation; change in bowel movement frequency; and change in stool consistency. IBS can be classified into four subtypes: constipation-predominant (IBS-C); diarrhoea-predominant (IBS-D); mixed bowel habit (IBS-M), and unclassified (IBS-U). A fifth type is post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS), which occurs after a gastrointestinal infection.1

IBS has a multifactorial aetiology.5 Its development may be influenced by aspects such as altered gastrointestinal motility,5 visceral hypersensitivity,5,6 psychological disturbances (stress, anxiety and depression),7 dysbiosis and/or gender predisposition8,9 or genetics.10–12 A study has been made of the relationship between dysbiosis, defined as an alteration in the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota, and increased hypersensitivity to pain and increased intestinal mucosa permeability.2 Generally, an increase is found in bacteria with pro-inflammatory action, such as enterobacteria13 and a decrease in bacteria with anti-inflammatory action, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii.14 Levels of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which modulate the microbiota and immune system, are also low.13,14

The complexity and diversity of symptoms makes the choice of treatment for IBS difficult, so a multidisciplinary approach is often necessary. The treatment chosen by patients is usually dietary (48%), as opposed to drug therapy (29%) or psychotherapy (23%).15 The most commonly used dietary models have been a low FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) diet and a gluten-free diet. A low FODMAP diet does not contain short-chain fermentable carbohydrates, found primarily in fruits, vegetables, dairy and wheat.16 Most patients can report improvement by following these recommendations.17,18 However, long-term use is not advised because of the risk of nutritional deficiencies and alteration of the microbiota.19 There are few studies on patient follow-up after reintroduction of FODMAP.20 It has been reported that soluble fibre intake can improve symptoms, as it favours the microbiota, accelerates intestinal transit and improves stool consistency.21 However, it can also increase abdominal distension and pain, so it should be taken gradually and assessed on an individual basis.19,22–24 If the symptoms significantly affect quality of life, drug treatment and/or psychotherapy is added. The drugs used include antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of general symptoms.1 Psychotherapy includes cognitive behavioural therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy, which can be effective in the long term.25

When dietary changes and drug treatment are not sufficient, supplements such as peppermint oil, aloe vera and psyllium are used.21 However, because of the clear link between dysbiosis and the development of IBS, the supplements with the greatest potential are probiotics, live microorganisms capable of establishing themselves in the gut microbiota. Several studies have shown the ability of probiotics to stabilise the intestinal wall and reduce visceral hypersensitivity, thus improving symptoms.13,26,27Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium genera have been studied the most.28 The British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines indicate that probiotics may be effective in relieving general symptoms and abdominal pain, but it is not possible to recommend a specific species or strain.19 Ford et al.29 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of probiotics in improving IBS.29 Individuals reported no adverse effects associated with probiotic consumption. Although the authors noted that certain individual probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum, E. coli and Streptococcus faecium), as well as some combinations of strains (Lacclean Gold [Bifidobacterium longum, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium lactis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Streptococcus thermophilus]) and the combination of seven strains (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium longum and Streptococcus thermophilus) could improve overall symptoms, they did not obtain robust results to determine which species is more effective, either individually or in combination. The review by Ford et al.29 is interesting as a starting point for the design of human studies to verify the potential benefits of consuming such combinations. However, the authors did not evaluate some of the important factors in the efficacy of probiotics, such as treatment duration or dose, or the analysis of individual symptoms. Therefore, the aim of this review is to provide an updated assessment of the effectiveness of probiotics in monotherapy and in combination with other strains and other agents on IBS symptoms, analysing the influence of the duration of the treatment or the doses used.

MethodsThis systematic review was carried out following the recommendations of the "Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews" (PRISMA).30 Adherence to the PRISMA checklist (reference items for publishing systematic reviews) is set out in the supplementary material section (Appendix A, Supplementary Table 1). The PubMed database was used to search for and select articles. The keywords used in the search were: "gut microbiota", "irritable bowel syndrome", "strain", "treatment" and "probiotics". Inclusion criteria applied were: date of publication after the year 2000, trials based on randomised controlled clinical trials, studies conducted in humans, and written in English. The articles for the review were identified separately by two different authors (C.R.S. and M.S.F.P.). First, the titles, abstracts and keywords of the articles were assessed to select those that might meet the inclusion criteria. Second, the authors reviewed each of the selected articles in their entirety to determine their suitability for inclusion in the review study. Disagreements between the authors were resolved by discussion. At this stage, various articles were eliminated from the review for one of the following reasons: duplication with another previously selected article; inappropriate study population; article not based on the authors' original trials; and methodology not related to the symptoms of the disease. Authors C.R.S. and M.S.F.P. separately and independently assessed the full text of the articles included in the review and carried out data extraction and synthesis using a predefined format. As a result, the following data were collected: study reference (authors, journal and year of publication); description of participants (sample size, diagnostic criteria, gender, age); characteristics of study design and probiotic supplementation (number of experimental groups, probiotic strains, dosage and duration); symptom scores (abdominal pain rating scales such as Abdominal Pain Severity-Numeric Rating Scale [APS-NRS]); bloating, diarrhoea, vomiting, constipation, defaecation frequency, sensation of evacuation, stool consistency, gas, nausea and dyspepsia; disease severity (Irritable Bowel Syndrome-Severity Scoring System [IBS-SSS], Global Improvement Scale [GIS]); and quality of life questionnaires (Irritable Bowel Syndrome-Quality of Life [IBS-QoL], Irritable Bowel Syndrome Adequate Relief [IBS-AR], RAND-36, SF-12/SF-36); and outcomes of interventions. With the results extracted, given the variability of the quantification systems used, a positive outcome (effective treatment of the probiotic strain for the improvement of symptoms) was considered when a significant statistical difference was evident between the experimental group and the placebo group (p < 0.05), and a negative outcome when the difference was not significant. The authors then checked the extracted data to confirm they were fit for purpose. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion of the data until consensus was reached. The methodological quality of the articles included was assessed individually using the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias tool for randomised controlled trials.31 A total of seven items were assessed (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and staff, blinding of outcome assessments, missing results, selective reporting of results and other types of bias). Each of the items was rated as "low risk of bias", "uncertain risk of bias" or "high risk of bias". A summary of the risk of bias for each study is shown in the supplementary material section (Appendix A, Supplementary Table 2).

Results and discussionFrom a total of 289 articles obtained through the search, 89 were selected after reviewing their titles, abstracts and keywords. After reading their full texts, 71 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 18 articles were included in this systematic review (the flow chart of the article selection process is shown in Appendix A, Supplementary Fig. 1). Overall, after analysis of the risk of bias, the methodological quality of the articles included was excellent. Only detection and attrition biases were rated as uncertain/high risk in nine and six studies, respectively.

The main objective of most of the studies was to evaluate the effectiveness of probiotic use in relieving the overall symptoms of IBS. The main symptom assessed was abdominal pain.

Twelve trials used the Rome III diagnostic criteria, three used Rome II,32–35 and one used Rome IV.36 One study does not mention the type of criteria used.37 The studies also used different methods to measure variation in IBS symptoms. Most studies used scales, including: Visual Analogue Scale35,38–43; Likert Scale28,32,35,37,42,44–47; Bristol Scale28,35,38–42,45,48; GIS47; and APS-NRS.36 In addition to these scales, different questionnaires were also used: IBS-SSS34,36,47–49; IBS-AR42; IBS-QoL46,48,49; RAND-36 and SF-12/SF-3634,44; and an unspecified quality of life questionnaire.35 The articles refer to the following probiotic genera: Bacillus, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Lactococcus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus and Propionibacterium; in different combinations and dosages.

Effectiveness in trials of a single strain compared to placeboSix randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies were included. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the sample

Description of studies evaluating the effectiveness of a probiotic strain.

| Study | Study design | Size (n) | Experimental groupsa | Gender(M or F) | Age (years) | Probiotic | Posology (dosage)b | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majeed et al. (2016)38 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 36 | 1 (n = 18)2 (n = 18) | M (n = 17)F(n = 19) | 18−55 | Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 | 1 – 0 – 0(2 × 109 CFU/day) | 90 days(12−13 weeks) |

| Guglielmetti et al. (2011)44 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 122 | 1 (n = 62)2 (n = 60) | M (n = 40)F (n = 82) | 18−68 | Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 | 1 – 0 – 0(1 × 1010 CFU/day) | 4 weeks |

| O'Sullivan and O'Morain (2000)37 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 24 | 1 (n = 12)2 (n = 12) | M (n = 4)F (n = 20) | 24−60 | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | 2 – 0 – 2(1 × 109CFU/day) | 20 weeks |

| Sinn et al. (2008)28 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 40 | 1 (n = 20)2 (n = 20) | M (n = 14)F (n = 26) | 18−70 | Lactobacillus acidophilus-SDC | 1 – 0 – 1(2 × 109 CFU/mL) | 4 weeks |

| Martoni et al. (2020)36 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 330 | 1 (n = 109)2 (n = 111)3 (n = 110) | M (n = 167)F (n = 163) | 18−70 | (2) Lactobacillus acidophilus DDS-1(3) Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis UABla-12 | 1 – 0 – 0(1 × 1010 CFU/day) | 6 weeks |

| O'Mahony et al. (2005)35 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 75 | 1 (n NS)2 (n NS)3 (n NS) | M (n = 27)F (n = 48) | 18−73 | (2) Lactobacillussalivarius UCC4331(3) Bifidobacteriuminfantis 35624 | 1 – 0 – 0(1 × 1010 CFU/day) | 8 weeks |

NS: not specified; M: male; F: female.

The total number of studies involved 603 adults with IBS, aged 18−73. Two studies included 330 and 122 patients,36,44 while the rest had fewer than 75 subjects. Four studies included higher ratios of females.28,35,37,44 The duration of treatment ranged from four to 20 weeks. The pharmaceutical form used was the capsule. The dose ranged from 1 × 109 to 1 × 1010 CFU/day. Some of the trials established two experimental groups: placebo group (1) and probiotic group (2). Others had three experimental groups35,36: one placebo group (1), and two experimental groups (2 and 3) (Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, respectively). The most studied genera were Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, evaluated in four28,35–37 and three35,36,44 of the five trials, respectively. One study used Bacillus coagulans.38

The scores evaluated and the results obtained are shown in Table 2.

Scores evaluated and results obtained in the probiotic strain effectiveness studies.

| Study | Scores | Resultsa |

|---|---|---|

| Majeed et al. (2016)38 | 1 Overall symptom relief (bloating, vomiting, diarrhoea, defaecation frequency, abdominal pain)2 Assessment of disease severity3 Quality of life | 1 (+)2 (+)3 (+) |

| Guglielmetti et al. (2011)44 | 1 Reduction in general symptoms2 Changes in variables: abdominal pain, bloating, defaecation urgency, frequency of intestinal transit, sensation of incomplete evacuation.3 Quality of life | 1 (+)2 Abdominal pain (+), bloating (+), urgency (+), frequency (NSC) and incomplete evacuation (NSC)3 (+) |

| O'Sullivan and O'Morain (2000)37 | 1 Reduced abdominal bloating, pain and defaecation frequency | NSC |

| Sinn et al. (2008)28 | 1 Reduction in abdominal pain2 Satisfaction with intestinal transit, straining to defecate, sensation of incomplete evacuation, defaecation frequency and stool consistency | 1 (+)2 Satisfaction with transit (+), straining to defecate (+), incomplete evacuation (+), frequency and consistency (NSC) |

| Martoni et al. (2020)36 | 1 Changes in abdominal pain severity2 IBS-SSS3 Stool consistency, quality of life and product tolerability | 1 (+) > in group (2)2 (+)3 Consistency (+), quality of life (NSC), tolerability (NSC) |

| O'Mahony et al. (2005)35 | 1 Reduction in abdominal pain2 Bloating or distension3 Difficult defaecation4 Stool frequency and consistency5 Quality of life | 1 (+) (3), (NSC) (2)2 (+) (3), (NSC) (2)3 (+) (3), (NSC) (2)4 (NSC)5 (NSC) |

IBS-SSS: Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptom Severity Score; NSC: no significant change.

A trend was found towards improvement of general IBS symptoms, except in studies with Lactobacillus rhamnosus37 and Lactobacillus salivarius.35 The study by O'Sullivan and O'Morain37 had the longest duration (20 weeks) and the highest dose (1 × 1010 CFU/day, four times/day). This could suggest that the most important aspect for the efficacy of a treatment is the strain used, and that the duration or dose should be adjusted to the minimum amount and time that leads to significant improvements. Lactobacillus acidophilus was able to minimise the overall symptoms of IBS and improve symptoms such as intestinal transit and stool consistency.28,36 In the study by Sinn et al.,28Lactobacillus acidophilus was able to reduce abdominal pain, improve bowel habit and straining to defecate and eliminate the sensation of incomplete evacuation (p < 0.05). These interesting results were also obtained by Martoni et al.,36 who also evaluated the IBS-SSS, achieving significant improvements, both in the overall score and in each item separately, and stool consistency was also improved. This probiotic showed positive results in a range of four to six weeks,28,36 with doses of 2 × 109 CFU twice/day28 and 1 × 1010 CFU/day.36

Three strains of Bifidobacterium were studied, with similar results.35,36,44Bifidobacterium bifidum showed a significant reduction in abdominal pain and bloating, and an improvement in defaecation urgency. In addition, an improvement in quality of life was also found, both in physical and mental health aspects, after completing the SF-12 questionnaire.47Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis significantly reduced the severity of abdominal pain, the overall IBS-SSS score and that of each item separately.36 Stool consistency also significantly improved.36Bifidobacterium infantis significantly reduced abdominal pain, abdominal bloating or distension and difficult defaecation. Its efficacy on stool frequency and consistency and quality of life was not significant.35 Although the duration of treatment was longer in the study by O'Mahony et al.35 (eight weeks) than in the other two studies,36,44 the authors found that the Bifidobacterium infantis strain was already producing the above-mentioned benefits at four weeks. The doses used were similar in all three studies (1 × 109–1 × 1010 CFU/day). The larger sample size in the studies by Guglielmetti et al.44 and Martoni et al.36 could make the results more robust.

The study with Bacillus coagulans38 (2 × 109 CFU/day for 90 days) showed significant improvement in abdominal bloating, vomiting, diarrhoea, defaecation frequency, abdominal pain and stool consistency. In this study, the patients had IBS-D, so this probiotic seems to be more targeted to that subtype of the disease.

After analysis of these studies, treatment with Bifidobacterium bifidum may be the most effective intervention in improving IBS symptoms, as it showed positive results at a lower dose (1 × 109 CFU/day) and in only four weeks.44 However, further studies are warranted to assess in parallel different strains of Bifidobacterium at the same dose and duration.

Effectiveness in trials of strain combinations compared to placeboTen studies on the effectiveness of different combinations of probiotic strains as a treatment for IBS were evaluated. The characteristics of these studies are shown in Table 3.

Description of studies assessing the effectiveness of different combinations of probiotic strains.

| Study | Study design | Size(n) | Experimental groupsa | Gender(M or F) | Age (years) | Probiotic | Posology (Dosage)c | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ishaque et al. (2018)48 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 360 | 1 (n = 179)2 (n = 181) | M (n = 281)F (n = 79) | 18−55 | Bio-Kult®: B. subtilis PXN 21, 4 strains of Bb. spp., 7 strains of L. spp., Lc. lactis PXN 63, and S. thermophilus PXN 66 | 2 – 0 – 2(8 × 1012 CFU/day) | 16 weeks |

| Yoon et al. (2014)45 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 49 | 1 (n = 24)2 (n = 25) | M (n = 17)F (n = 32) | 19−75 | LacClean Gold-S®: Bb. bifidum (KCTC 12199BP), Bb. lactis (KCTC 11904BP), Bb. longum (KCTC 12200BP), L. acidophilus (KCTC 11906BP), L. rhamnosus (KCTC 12202BP) and S. thermophilus (KCTC 11870BP) | 1 – 0 – 1(1000 mg/day)(5 × 109 CFU/capsule) | 4 weeks |

| Sisson et al. (2014)49 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 152 | 1 (n = 52)2 (n = 100) | M (n = 57)F (n = 129) | 18−65 | Symprove: L. rhamnosus NCIMB 30174, L. plantarumNCIMB 30173, L. acidophilusNCIMB 30175 and E. faecium NCIMB 30176 | 1 mL/kg/day(1 × 109 CFU/day) | 12 weeks |

| Saggioro (2004)32 | Randomised, placebo-controlled | 70 | 1 (n = 20)2 (n = 24)3 (n = 26) | M (n = 31)F (n = 39) | 26−64 | (2) L. Plantarum LP0 1 + Bb. breve BR0(3) L. plantarumLP01 + L. acidophilus LA02 | 1 – 0 – 1(5 × 109 CFU/mL) | 4 weeks |

| Jafari et al. (2014)43 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 108 | 1 (n = 54)2 (n = 54) | M (n = 43)F (n = 65) | 20−70 | Probio-Tec® Quatro-cap-4: Bb. animalis subsp. lactisBB-12, L. acidophilus LA-5, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus LBY-27, S. thermophilus STY-31 | 1 – 0 – 0(4 × 109 CFU/day) | 4 weeks |

| Kajander and Korpela (2006)34 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 86 | – | – | – | L. rhamnosus GG, L. rhamnosus Lc705, P. freudenreichii ssp. shermanii JS and Bb. breve Bb99 | 1 – 0 – 0(8−9 × 109 CFU/day) | 6 months |

| Sadrin et al. (2020)39 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 80 | 1 (n = 40)2 (n = 40) | M (n = 16)F (n = 39) | 30−60 | L. acidophilus NCFM and L. acidophilus subsp.helveticus LAFTI L10 | 2 – 0 – 0(5 × 109 CFU/capsule) | 9 weeks |

| Ringel-Kulka et al. (2011)46 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 60 | 1 (n = 31)2 (n = 29) | M (n = 17)F (n = 43) | 18−65 | L. acidophilus NCFM and Bb. lactis Bi-07 | 1 – 0 – 1(2 × 1011 CFU/day) | 8 weeks |

| Skrzydło-Radomańska et al. (2021)47 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 48 | 1 (n = 23)2 (n = 25) | M (n = 17)F (n = 31) | 18−70 | NordBiotic: 5 strains of Lactobacillus, 4 strains of Bifidobacterium and S. thermophilus | 1 – 0 – 1(2.5 × 109 CFU/day) | 8 weeks |

| Han et al. (2017)42 | Randomised, double-blind, controlled (double coated vs uncoated) | 46 | 1 (n = 23)b2 (n = 23) | M (n = 24)F (n = 22) | 19−65 | Duolac Care: L. acidophilus, L. plantarum,L. rhamnosus, Bb. breve, Bb. lactis, Bb. longumand S. thermophilus | 1 – 0 – 1(5 × 109 CFU/day) | 4 weeks |

B: Bacillus; Bb: Bifidobacterium; L: Lactobacillus; Lc: Lactococcus; S: Streptococcus; E: Enterococcus; P: Propionibacterium; M: male; F: female.

They included a total of 1059 adult patients aged 18–75. Three studies had more than 100 patients,43,48,49 with the rest evaluating from 46 to 86 subjects. In terms of gender distribution, in one study the majority were male (78%),48 while the remaining eight studies had a higher proportion of females. The duration of treatment ranged from four to 16 weeks. In eight studies the treatment was administered by capsule, in one in liquid form Sisson et al.,49 and in another, in the form of powder for solution.34 The dose ranged from 2500 million to 8 billion CFU/day.

The scores studied and the results obtained are shown in Table 4.

Scores evaluated and results obtained in studies on the effectiveness of different combinations of probiotic strains.

| Study | Scores | Resultsa |

|---|---|---|

| Ishaque et al. (2018)48 | 1 Changes in the IBS-SSS2 Changes in GI symptom severity and IBS-QoL questionnaire | 1 (+)2 (+) |

| Yoon et al. (2014)45 | 1 Overall symptom relief2 Intensity of abdominal pain and bloating, defaecation frequency, stool consistency | 1 (+)2 Intra-group pain and swelling (+), inter-group pain and swelling (NSC), frequency (NSC) and consistency (NSC) |

| Sisson et al. (2014)49 | 1 Changes in the IBS-SSS2 Changes in the IBS-QoL and changes in each component of the IBS-SSS | 1 (+)2 IBS-QoL (NSC), abdominal pain (+), pain frequency (NSC), bloating (NSC), satisfaction with bowel habit (+), quality of life (NSC) |

| Saggioro (2004)32 | 1 Reduction in abdominal pain2 Severity of symptoms (constipation, diarrhoea, bloating, gas, headache, nausea, dyspepsia) | 1 Reduction in pain: 29.5% (1), 45% (2), 49% (3).2 Reduction in symptom severity: 14.4% (1), 56% (2), 55.6% (3) |

| Jafari et al. (2014)43 | 1 Reduction in abdominal bloating2 Changes in abdominal pain, sensation of incomplete evacuation, general relief of symptoms at least 50% of the time. | 1 (+)2 Abdominal pain (+), incomplete evacuation (+), general relief (+). |

| Kajander and Korpela (2006)34 | 1 Changes in IBS-SSS2 Individual symptoms, bowel habits and quality of life. | 1 (+)2 (NSC) |

| Sadrin et al. (2020)39 | 1 Reduction in abdominal pain2 Changes in bloating, flatus, stomach rumbling, "composite score" (abdominal pain, bloating, flatus and stomach rumbling), stool consistency. | 1 (NSC)2 Swelling (NSC), flatus (+), rumbling (NSC), "composite score" (+) and consistency (NSC) |

| Ringel-Kulka et al. (2011)46 | 1 Overall symptom relief and satisfaction with treatment2 Change in severity of symptoms: abdominal pain and bloating, postprandial pain, stool frequency and consistency | 1 (NSC)2 Abdominal pain (NSC), abdominal bloating (+), postprandial pain (NSC), stool frequency (NSC), consistency (NSC) |

| Skrzydło-Radomańska et al. (2021)47 | 1 Changes in total IBS-SSS and in each item. Changes in the GIS2 Changes in stool consistency, severity of pain and gas, defaecation urgency, tenesmus, intervention effect and adverse effects | 1 IBS-SSS (+), abdominal pain (+), pain frequency (NSC), bloating (NSC), satisfaction with bowel habit (NSC), quality of life (+), GIS (+).2 (NSC) |

| Han et al. (2017)42 | 1 General symptom relief2 Stool consistency and normal/hard/liquid stool ratio3 Improvement in abdominal pain, discomfort and bloating, flatulence, defaecation urgency and mucus in the stool. | 1 Intragroup (+); Intergroup: 3rd week (+), 4th week (NSC)2 Consistency (NSC) and ratio (+)3 Intragroup (+), intergroup (NSC) |

IBS-SSS: Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptom Severity Score; GI: Gastrointestinal; IBS-QoL: Quality of Life Questionnaire; GIS: Global Improvement Scale.

b (1): Placebo group; (2): Probiotic group: L. Plantarum LP0 1 + Bb. breve BR0; (3) Probiotic group: L. plantarum LP01 + L. acidophilus LA02. No statistical study.

The different combinations of probiotics could be classified into three groups: group 1 (various strains of Lactobacillus); group 2 (Lactobacillus + Bifidobacterium); and group 3 (Lactobacillus + Bifidobacterium + Streptococcus).

Within group 1, the combination of two strains of L. acidophilus39 (5 × 109 CFU/capsule for nine weeks) showed no significant differences in reducing pain, bloating or abdominal noises, although it did improve flatus. The improvement obtained was significant, however, when considering these four symptoms as a composite score. Stool consistency also showed no significant improvement. In contrast, the combination of L. plantarum and L. acidophilus32 (5 × 109 CFU/mL for four weeks) reduced overall symptoms, although this study did not provide a statistical analysis.

Adding Enterococcus faecium to three Lactobacillus strains (1 × 109 CFU/day for 12 weeks) significantly improved the IBS-SSS total score and abdominal pain and satisfaction with bowel habit.49 Therefore, the inclusion of Enterococcus in the Lactobacillus formulation could be beneficial.

In group 2, L. plantarum and Bifidobacterium breve32 (5 × 109 CFU/mL for four weeks) reduced pain and general symptoms, but this study also did not provide a statistical analysis. The combination of L. acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis46 (2 × 1011 CFU/day for eight weeks) only produced a significant improvement in abdominal bloating after four weeks of treatment. Kajander and Korpela34 added Propionibacterium to the combination (8−9 × 109 CFU/day for six months), with this only resulting in a significant decrease in the total IBS-SSS score.

A mixture of different strains of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Streptococcus was used in group 3. The four-strain trial by Jafari et al.43 (4 × 109 CFU/day for four weeks) showed a significant decrease in abdominal pain and bloating and in the sensation of incomplete evacuation, and relief of general symptoms. Yoon et al.45 (1 × 1010 CFU/day for four weeks) showed that their combination of six strains was significantly effective in alleviating IBS symptoms overall. A decrease in abdominal pain and bloating was also observed, although this was not significant. Skrzydło-Radomańska et al.47 used the largest number of strains (10 strains), with doses of 2.5 × 109 CFU/day for eight weeks, obtaining an overall improvement in symptom severity and quality of life, and a significant decrease in the total IBS-SSS score. Other parameters, such as changes in stool consistency, gas, defaecation urgency, tenesmus and intervention effect, showed no significant differences.

The design of the study by Han et al.42 was different, as it assessed possible differences in the effectiveness of this probiotic combination encapsulated with double-coating compared to the same formulation uncoated (5 × 109 CFU/day for four weeks). Significant overall symptom relief was found in the second week, but this was not sustained at the end of the study. The visual analogue scale (VAS) revealed significant improvements in symptoms such as abdominal pain, discomfort and bloating, flatulence, defaecation urgency and presence of mucus in the stool, compared to baseline values; there were no significant differences between groups. The only parameter with significant differences between groups was stool consistency, which was better in the coated group.42 The probiotic formulation used may have potential benefits for IBS symptoms, but the double coating does not appear to make a difference.

Ishaque et al.48 incorporated Bacillus and Lactococcus genera to these three probiotic genera, creating a 14-strain formulation (8 × 1012 CFU/day for 16 weeks), and found a significant improvement in symptom severity, total score and the five items that make up the IBS-SSS. Using the IBS-QoL, quality of life improved significantly in the experimental group.

In general, the results obtained are very diverse according to the multi-strain probiotics used. The combination of three Lactobacillus strains49 (L. rhamnosus, L. plantarum and L. acidophilus) obtained interesting results in several parameters, although it was not remarkable in terms of improvement of patients' quality of life. The best-performing trial was that by Ishaque et al.48 with the most complex probiotic combination, containing 14 strains of different species. However, because it contained so many strains, it involved the highest dose (8 × 1012 CFU/day), which resulted in a regimen that was more difficult to follow (four capsules/day). The combination that offered the most convenient dosage (one capsule/day), at a lower dose (4 × 109 CFU/day) and with which positive results were obtained in four weeks, was the one composed of two strains of Lactobacillus (L. acidophilus LA-5 and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus LBY-27), one of Bifidobacterium (Bb. animalis subsp. lactis BB-12) and one of Streptococcus (S. thermophilus STY-31) (Probio-Tec), which alleviated general symptoms in 85% of patients.43 Quality of life was not measured, but given the aspects of improvement, it is very likely that patients would have reported an improvement in their daily lives. This combination is in line with that proposed by Ford et al.29

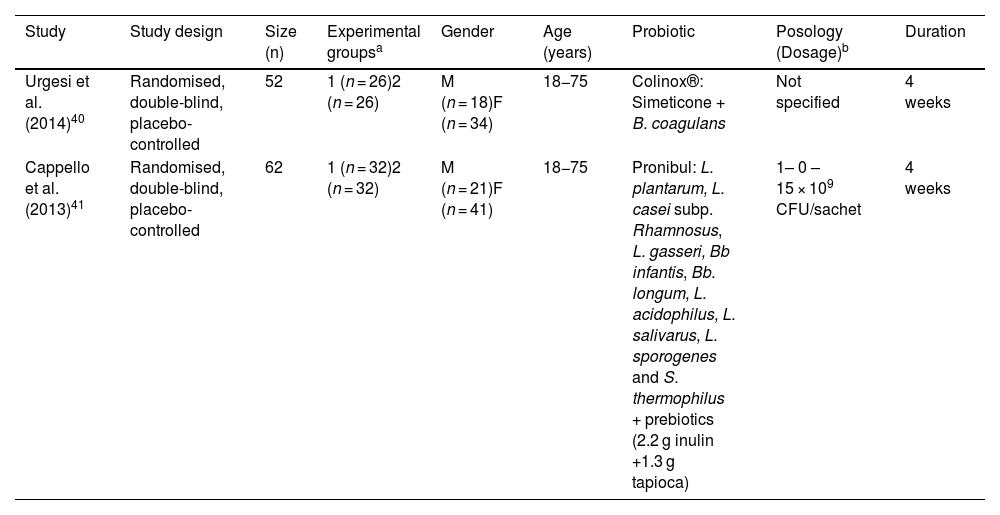

Effectiveness in trials of probiotics in combination with other agentsIn the absence of strong scientific evidence to date for the use of probiotics alone as a single treatment to alleviate all IBS symptoms, some studies have assessed the joint efficacy of probiotics with other agents, which may exert a synergistic effect to improve symptoms. The characteristics of the studies included in this section are shown in Table 5.

Description of studies assessing the effectiveness of different combinations of probiotic strains with other agents.

| Study | Study design | Size (n) | Experimental groupsa | Gender | Age (years) | Probiotic | Posology (Dosage)b | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgesi et al. (2014)40 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 52 | 1 (n = 26)2 (n = 26) | M (n = 18)F (n = 34) | 18−75 | Colinox®: Simeticone + B. coagulans | Not specified | 4 weeks |

| Cappello et al. (2013)41 | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 62 | 1 (n = 32)2 (n = 32) | M (n = 21)F (n = 41) | 18−75 | Pronibul: L. plantarum, L. casei subp. Rhamnosus, L. gasseri, Bb infantis, Bb. longum, L. acidophilus, L. salivarus, L. sporogenes and S. thermophilus + prebiotics (2.2 g inulin +1.3 g tapioca) | 1– 0 – 15 × 109 CFU/sachet | 4 weeks |

B: Bacillus; L: Lactobacillus; Bb: Bifidobacterium; S: Streptococcus; M: male; F: female.

These studies involved 114 adult patients in total, aged 18–75. The duration of treatment was four weeks. The dosage forms used were capsule,40 and powder for solution.41 The dose of probiotic administered is only specified in one of the studies, being 1 × 1010 CFU/day.41

Urgesi et al.40 evaluated a combination of Bacillus coagulans and simeticone (Colinox®). Cappello et al.41 evaluated a symbiotic mixture composed of nine probiotic strains of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Streptococcus species, inulin and tapioca (resistant starch) (Pronibul).

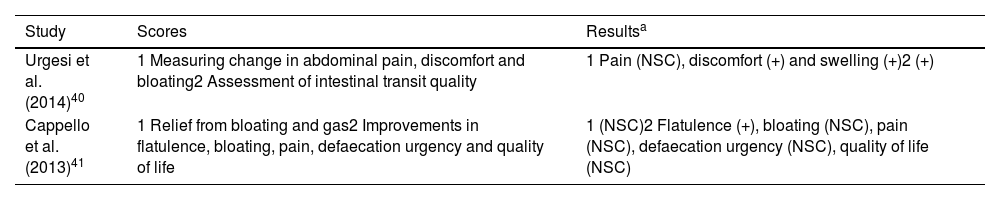

The scores evaluated are listed in Table 6 with the results obtained.

Scores evaluated and results obtained in studies on the effectiveness of different combinations of probiotic strains with other agents.

| Study | Scores | Resultsa |

|---|---|---|

| Urgesi et al. (2014)40 | 1 Measuring change in abdominal pain, discomfort and bloating2 Assessment of intestinal transit quality | 1 Pain (NSC), discomfort (+) and swelling (+)2 (+) |

| Cappello et al. (2013)41 | 1 Relief from bloating and gas2 Improvements in flatulence, bloating, pain, defaecation urgency and quality of life | 1 (NSC)2 Flatulence (+), bloating (NSC), pain (NSC), defaecation urgency (NSC), quality of life (NSC) |

Colinox® reduced abdominal bloating and discomfort and significantly improved stool consistency.40 Pronibul decreased the severity of gas in IBS patients.41 For other variables, such as bloating, abdominal pain and defaecation urgency, there were no significant differences. In view of these results, it does not appear that the addition of prebiotics or other active ingredients would provide greater relief of IBS symptoms compared to probiotics alone.

LimitationsA possible methodological limitation was not to include non-English-language papers, as cited in the inclusion criteria. However, we found there was only one study that was not considered, in Spanish, the full text of which was not available. Another possible limitation was the use of a single database to search for articles (PubMed), although given the biomedical research nature of this database, it is likely that almost all of the clinical studies covered by this review were assessed.

In terms of limitations encountered in clinical trials, in general, the sample size of the studies included is low. Only five studies included more than 100 patients.36,43,44,48,49 Furthermore, with small sample sizes it is difficult to discern between the different subtypes of IBS. Studies with a larger population would be warranted to address these limitations.

The duration of the studies was short. Only five studies lasted 12 weeks or longer,34,37,38,48,49 and only four trials followed up after finishing treatment35,42,44,46,49. Some probiotics may be effective over a longer period.

The diagnostic approach to IBS differed between studies, which may result in some of the patients included not meeting the current diagnostic criteria. However, these trials only include patients with noticeable (moderate to severe) symptoms, which may minimise this limitation.

There is great heterogeneity in the tools used to measure changes in symptoms, which complicates comparison between studies.

Few studies include other agents (fibre, prebiotics, drugs), so robust conclusions cannot be drawn.

ConclusionsProbiotics could be considered as a potential treatment to improve the overall symptoms of IBS, especially abdominal pain and bloating, and thus improve quality of life. In terms of individual probiotics, the genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Bacillus could be useful in treating symptoms. Specifically, the strain Bifidobacterium bifidum yielded the most effective results, considering a lower dose and duration of treatment (1 × 109 CFU/day for four weeks). The combination of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Streptococcus strains was striking for its role in alleviating a greater number of symptoms with a better ratio between dose (4 × 109 CFU/day) and duration of treatment (four weeks). The combination of probiotics with other agents did not provide superior benefits, although the number of items assessed was low. Due to the limitations encountered, the results should be interpreted with caution. Future trials should confirm these results and analyse the differences between individual and combined treatments. In addition, probiotics should be tested for sustained effects over time. Longer patient follow-up would also corroborate the absence of adverse effects.

FundingThis study did not receive any type of funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.