To provide practical recommendations for the evaluation and management of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes mellitus.

ParticipantsMembers of the Diabetes Mellitus Working Group of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (SEEN).

MethodsThe recommendations were made based on the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to establish both the strength of the recommendations and the level of evidence. A systematic search was made in MEDLINE (PubMed) for the available evidence on each subject, and articles written in English and Spanish with an inclusion date up to 30 November 2019 were reviewed. This executive summary takes account of the evidence incorporated since 2013.

ConclusionsThe document establishes practical evidence-based recommendations regarding the evaluation and management of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Proporcionar unas recomendaciones prácticas para la evaluación y el manejo de la hipoglucemia en pacientes con diabetes mellitus.

ParticipantesMiembros del Grupo de Trabajo de Diabetes Mellitus de la Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición (SEEN).

MétodosLas recomendaciones se formularon según el sistema Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation para establecer tanto la fuerza de las recomendaciones como el grado de evidencia. Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en MED-LINE (PubMed) de la evidencia disponible para cada tema, y se revisaron artículos escritos en inglés y castellano con fecha de inclusión hasta el 30 de noviembre de 2019. En este resumen ejecutivo incluimos la evidencia reciente incorporada desde 2013.

ConclusionesEl documento establece unas recomendaciones prácticas basadas en la evidencia acerca de la evaluación y manejo de la hipoglucemia en pacientes con diabetes mellitus.

In 2013, the Diabetes Mellitus Working Group of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición, SEEN) drew up evidence-based recommendations on the evaluation and management of hypoglycaemia in patients with diabetes.1 That document now needs updating following the development of new therapies, the emergence of new evidence about the repercussions of hypoglycaemia and advances in technologies applied to diabetes.

Method for producing evidence-based clinical practice guidelinesThe recommendations were formulated according to the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for rating the strength of recommendations and the quality of evidence.2 A distinction is made between strong recommendations, expressed as "we recommend"/number 1, and weak recommendations, expressed as "we suggest"/number 2. The quality of the evidence is expressed with symbols: ⊕ very low; ⊕⊕ low; ⊕⊕⊕ moderate; and ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high.

Articles written in English and Spanish (PubMed) were reviewed with an inclusion date up to 28 February 2020. Once the recommendations had been formulated, they were discussed jointly by the Working Group. This executive summary includes the evidence incorporated since 2013.

Definition and classification of hypoglycaemiaRecommendations- -

We recommend evaluating the presence and severity of symptomatic or asymptomatic hypoglycaemia at each visit in people with type 1 (DM1) and type 2 (DM2) diabetes at risk of hypoglycaemia (1⊕⊕⊕○).

- -

We suggest that subjects with DM be alerted to the possibility of developing hypoglycaemia when their self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) reveals rapidly falling glucose levels or a level below 70 mg/dl (2⊕○○○).

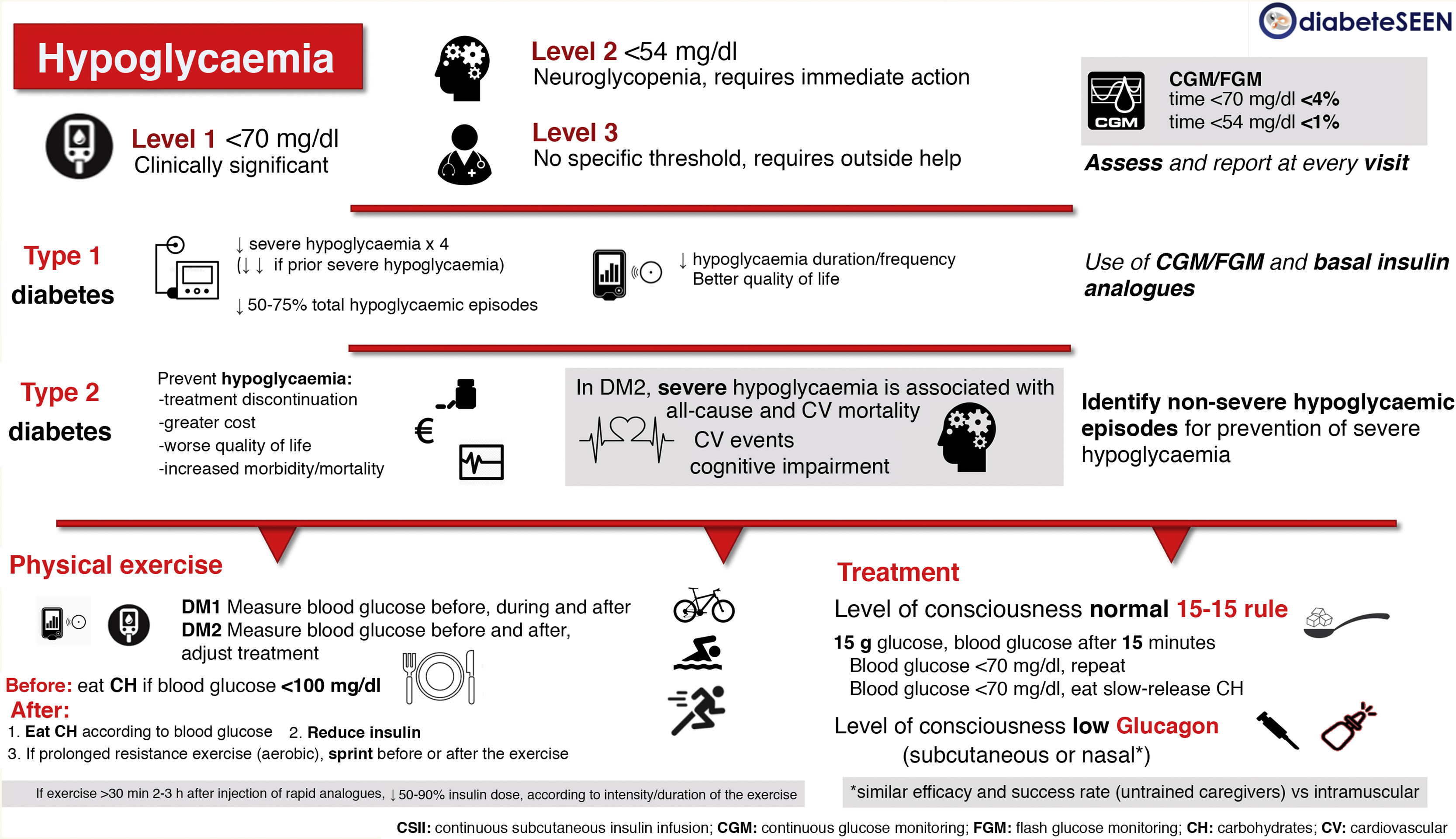

There is a lack of consensus on the clinical definition of hypoglycaemia, and in clinical practice it is classified according to its clinical consequences (Fig. 1).

Level 1 hypoglycaemia: blood glucose <70 mg/dl and >54 mg/dl, which can alert the person to take action. Considered clinically significant, regardless of the severity of the acute symptoms.

Level 2 hypoglycaemia: blood glucose <54 mg/dl. Threshold at which neuroglycopenic symptoms begin to appear and immediate action is required to resolve the episode.

Level 3 hypoglycaemia: Severe hypoglycaemia; there is no specified glucose threshold. A severe episode is characterised by an altered mental and/or physical state which requires external assistance from another person to resolve.

In subjects using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) or intermittent/flash glucose monitoring (FGM), time spent in hypoglycaemia is one of the parameters that should be assessed. The optimal goals are a time below 70 mg/dl <4% (includes the period of time below 54 mg/dl), and a time below 54 mg/dl <1%, both in adults with DM1 and in pregnant women with DM23 (Fig. 1).

Hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes mellitusRecommendations- -

We recommend prevention of hypoglycaemia through a suitable balance between insulin dose, diet and physical activity, as well as active monitoring using SMBG, especially when over five years since onset of DM (1⊕⊕⊕⊕).

- -

We recommend CGM or FGM, with or without continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion pump (CSII) therapy in patients with DM1 and frequent hypoglycaemia (severe or not) (1⊕⊕⊕⊕).

- -

In DM1, regardless of the insulin treatment modality (multidose therapy -MDI- or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion -CSII), CGM or FGM improves blood glucose control and reduces the incidence of hypoglycaemia (1⊕⊕⊕⊕). These benefits are correlated with the time of use of the device and/or with the number of FGM scans (1⊕⊕⊕⊕).

Different meta-analyses have shown that CSII therapy reduces the number of severe hypoglycaemic episodes by up to four times; the more previous episodes of severe hypoglycaemia a patient had, the greater the effect. A 50%–75% reduction in the total number of hypoglycaemic episodes has also been shown.

Both CGM and FGM, and automatic stoppage in patients with CSII, have been shown to reduce hypoglycaemia duration.4 New technologies based on artificial pancreas models improve blood glucose control and reduce hypoglycaemia compared to conventional insulin pump therapy.

Hypoglycaemia and type 2 diabetes mellitusRecommendations- -

We recommend preventing hypoglycaemia as a priority objective in DM2 due to its association with a greater likelihood of treatment discontinuation, higher cost, deterioration in quality of life (1⊕⊕⊕⊕) and increase in morbidity and mortality (1⊕⊕⊕○).

- -

We recommend identifying patients with DM2 who have been diagnosed with episodes of non-severe hypoglycaemia and/or receive treatment with insulin and/or secretagogues (sulfonylureas or repaglinide), to implement strategies for the prevention of severe hypoglycaemia (1⊕⊕⊕○).

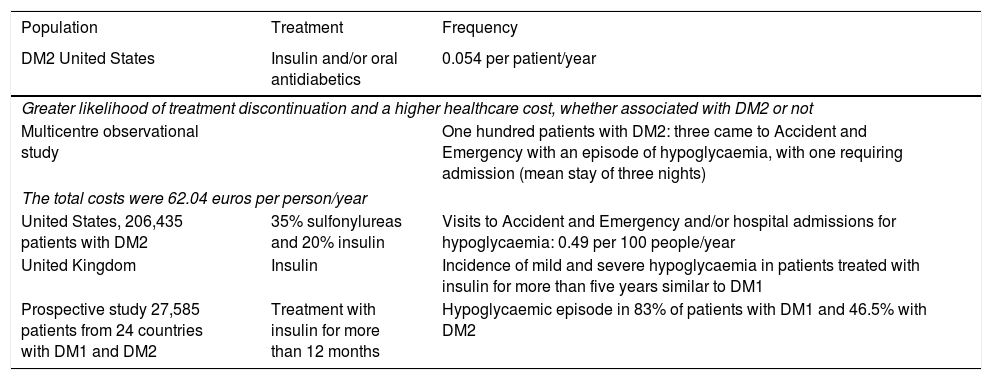

The incidence of hypoglycaemia in DM2 and the frequency of non-severe hypoglycaemia vary from one study to another (Table 1).

Hypoglycaemia in DM2.

| Population | Treatment | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| DM2 United States | Insulin and/or oral antidiabetics | 0.054 per patient/year |

| Greater likelihood of treatment discontinuation and a higher healthcare cost, whether associated with DM2 or not | ||

| Multicentre observational study | One hundred patients with DM2: three came to Accident and Emergency with an episode of hypoglycaemia, with one requiring admission (mean stay of three nights) | |

| The total costs were 62.04 euros per person/year | ||

| United States, 206,435 patients with DM2 | 35% sulfonylureas and 20% insulin | Visits to Accident and Emergency and/or hospital admissions for hypoglycaemia: 0.49 per 100 people/year |

| United Kingdom | Insulin | Incidence of mild and severe hypoglycaemia in patients treated with insulin for more than five years similar to DM1 |

| Prospective study 27,585 patients from 24 countries with DM1 and DM2 | Treatment with insulin for more than 12 months | Hypoglycaemic episode in 83% of patients with DM1 and 46.5% with DM2 |

- -

We recommend considering severe hypoglycaemia in DM2 as a factor associated with future all-cause mortality (1⊕⊕⊕○) and cardiovascular mortality (1⊕⊕⊕○).

- -

We recommend considering hypoglycaemia in DM2 as a factor associated with future cardiovascular events (1⊕⊕⊕○).

The post-hoc analyses of large randomised clinical trials (DEVOTE, ORIGIN, ADVANCE, ACCORD, VADT, LEADER and EXSCEL) have shown an increase in all-cause mortality in the months after a severe hypoglycaemic episode, a correlation between severe hypoglycaemia and a significant risk of cardiovascular mortality, and an association between severe hypoglycaemia and the future development of cardiovascular events. Different cohort studies have consistently demonstrated these same findings in patients with DM2 in routine clinical practice.5

In DM1, the evidence on this subject is very limited and the results inconsistent, so no recommendations or suggestions can be established.

Hypoglycaemia and physical exerciseRecommendations- -

We recommend that the glucose level should be checked (SMBG, CGM or FGM) in all people with DM1 before, during and after physical exercise (1⊕○○○).

- -

We recommend reducing the rapid-acting insulin bolus before exercise (when the exercise is 90−120 min after the insulin) and/or modifying carbohydrate (CH) intake, in order to prevent hypoglycaemia (1⊕⊕○○).

- -

We recommend eating CH before starting to exercise if blood glucose is below 100 mg/dl and after the exercise according to blood glucose (1⊕⊕○○).

- -

After exercise, we suggest reducing the insulin and/or eating CH (2⊕⊕○○) to prevent hypoglycaemia after the physical activity.

- -

In patients with DM2 on treatment with sulfonylureas or repaglinide and/or insulin, we recommend checking blood glucose before physical exercise (1⊕○○○) and adjusting drug treatment to prevent hypoglycaemia induced by exercise (1⊕⊕○○).

- -

We suggest that patients carry some form of diabetes identification (2⊕○○).

- -

We suggest not exercising for 24 h after a severe episode of hypoglycaemia due to the substantially higher risk of a major severe episode during exercise (2⊕⊕○○).

- -

After prolonged resistance exercise (predominantly aerobic), we suggest sprinting before or after the exercise as an alternative or complementary approach not related to insulin or food intake (2⊕⊕○○).

- -

We suggest the use of a mini-dose of glucagon to prevent exercise-induced hypoglycaemia in patients with DM1 (2⊕⊕⊕○).

If the exercise lasts longer than 30 min and takes place 2−3 h after the injection of rapid-acting analogues or 4−6 h after regular insulin, a 50%–90% reduction in the dose of insulin should be considered, depending on the intensity and duration of the planned exercise. In addition, extra CH (10−20 g) should be taken if blood glucose before exercise is less than 100 mg/dl. Taking glucose (fortified drinks or foods) at a rate of 1 g/kg/h improves performance and reduces the risk of hypoglycaemia.6

The blood glucose-lowering effect is greatest within 60−90 min following physical activity, although it persists for 6−15 h. Added to that, the counter-regulatory response is reduced, which can affect the perception of hypoglycaemia. Taking 5−6 mg/kg of caffeine prior to exercise reduces hypoglycaemia during and after exercise.6

Also recommended is reducing the basal insulin dose after exercise in line with the intensity and duration of the exercise. After the activity, it is advisable to check blood glucose and take a supplement of about 15−20 g of CH if the blood glucose is below 120 mg/dl. The timing of CH intake after exercise affects short-term glycogen synthesis; within 30 min after exercise (1–1.5 g CH/kg at intervals of 2–6 h) leads to higher levels of glycogen than when the intake is delayed 2 h.

Treatment of hypoglycaemiaRecommendations- -

In conscious patients, we recommend treatment of the hypoglycaemic episode preferably with 15−20 g of glucose, or with any CH containing that amount. This treatment should be repeated 15 min later if a capillary blood glucose test shows that the hypoglycaemia persists. When blood glucose has returned to normal, we recommend consuming a slow-release CH supplement to prevent a further hypoglycaemic episode (1⊕⊕○○).

- -

In unconscious patients, we recommend the administration of glucagon by subcutaneous injection (1⊕⊕○○) or nasally.

- -

In patients treated with insulin or secretagogues, we recommend periodically assessing their knowledge about the detection and treatment of hypoglycaemia, and reminding them of the need to always carry enough CH with them to treat a hypoglycaemic episode and to make sure they also have glucagon (1⊕OOO).

- -

We recommend re-assessing the treatment regimen if the patient experiences one or more episodes of level 3 hypoglycaemia, and arranging a temporary raising of their blood glucose targets to reduce the risk of future episodes in the case of patients with hypoglycaemia unawareness (1⊕⊕○○).

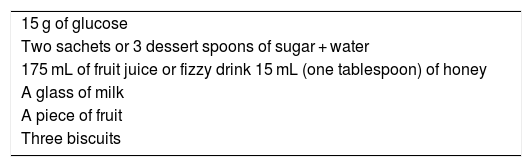

For the treatment of level 1 hypoglycaemia, administration of 15−20 g of glucose or equivalent is recommended1 (Table 2).

Level 3 hypoglycaemic episodes may require the subcutaneous, intramuscular or nasal administration of glucagon, and it should be checked periodically that the patient has a supply of this drug. The use of nasal glucagon has shown efficacy similar to intramuscular glucagon, with important differences in terms of ease of use. The mean time for administration (nasal vs conventional glucagon) was 16 s vs 1 min 53 s for trained caregivers, and 26 s vs 2 min 24 s for non-trained acquaintances. With the trained caregivers, the full dose of glucagon was received in 94% of cases with nasal glucagon vs 13% with intramuscular glucagon. With non-trained acquaintances, 93% received the full dose of nasal glucagon, but only 20% received a partial dose of conventional glucagon and the rest did not receive the drug.7 In addition, it can be stored at room temperature (up to 30 °C).

Hypoglycaemia unawarenessRecommendations- -

We recommend considering conventional risk factors and those that indicate impaired counter-regulation in patients with recurrent hypoglycaemia (1⊕⊕⊕⊕).

- -

We recommend avoiding hypoglycaemia for at least 2−3 weeks in patients with asymptomatic hypoglycaemia to improve their perception of hypoglycaemia (1⊕⊕○○).

- -

We recommend using strategies to improve the detection of hypoglycaemia if there is hypoglycaemia unawareness, including application of the Clarke test (1⊕⊕⊕○).

- -

We recommend using CGM as an effective tool when used with either CSII or MDI. The benefits are greater when used in a sensor-augmented pump (SAP) therapy system (1⊕⊕⊕○).

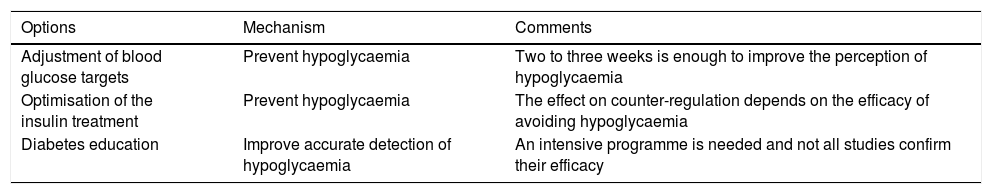

Hypoglycaemia unawareness affects approximately 20%–25% of people with DM1 and 10% of patients with DM2 treated with insulin, and increases the risk of severe hypoglycaemia. There are different strategies for the prevention and management of hypoglycaemia unawareness (Table 3).

Strategies for the prevention and management of hypoglycaemia unawareness.

| Options | Mechanism | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Adjustment of blood glucose targets | Prevent hypoglycaemia | Two to three weeks is enough to improve the perception of hypoglycaemia |

| Optimisation of the insulin treatment | Prevent hypoglycaemia | The effect on counter-regulation depends on the efficacy of avoiding hypoglycaemia |

| Diabetes education | Improve accurate detection of hypoglycaemia | An intensive programme is needed and not all studies confirm their efficacy |

In patients with DM1 and hypoglycaemia unawareness, CSII halves the episodes of hypoglycaemia and severe hypoglycaemia in particular (from 1.25 to 0.05 events/year). In the case of severe recurrent hypoglycaemia, transplantation of the pancreas and pancreatic islet cells should be considered as a treatment option.

CGM may be effective when used with either CSII or MDI in reducing the risk of severe hypoglycaemia and improving perception in patients with hypoglycaemia unawareness. The evidence for the use of CGM is more limited in people with DM2.

The use of CGM with the low-glucose suspend and predictive low-glucose suspend functions is a technological innovation with high therapeutic potential in hypoglycaemia unawareness,8 although results may be limited in patients with poor adherence and involvement in their own treatment.

Measurement of blood glucose and hypoglycaemiaRecommendations- -

We recommend SMBG when hypoglycaemia is suspected, after hypoglycaemia treatment until blood glucose returns to normal, and before engaging in activities that may increase their risk (exercise) or are potentially dangerous (driving, childcare, risk activities) (1⊕⊕⊕⊕).

- -

We recommend regularly checking the SMBG technique, the results and the ability to make appropriate decisions based on the results (1⊕○○○).

- -

We recommend CGM in people with DM1 (treated with MDI or CSII) to reduce the frequency of hypoglycaemia and the time spent in hypoglycaemia (1⊕⊕⊕○).

- -

We recommend CGM or FGM in DM1, as it reduces both the time spent in hypoglycaemia and the number of hypoglycaemic episodes (1⊕⊕ ○○).

In adult studies using CGM and FGM where reduction in hypoglycaemic episodes was the primary objective, there was a decrease both in subjects treated with MDI and those treated with CSII. In patients at increased risk of hypoglycaemia, a decrease was found in all levels of hypoglycaemia.

The studies carried out in DM2 are heterogeneous in terms of design, and include patients treated with basal insulin and/or oral antidiabetic therapy, MDI or CSII or MDI. In the DIAMOND study, in DM2 subjects treated with MDI, there was an improvement in blood glucose control with CGM, but not in the frequency of hypoglycaemia.

In patients with DM2 treated with insulin and with inadequate blood glucose control (A1c 8.8%), despite not inducing changes in blood glucose control, FGM reduced the time spent in hypoglycaemia by 43%. In DM1, FGM has been shown to reduce the time in hypoglycaemia by 38% six months after the intervention.9

Hypoglycaemia and workRecommendations- -

We recommend the use of CGM/FGM and also of certain basal insulin analogues or CSII in DM1 (1⊕⊕⊕○). In DM2, we recommend the use of non-blood glucose-lowering drugs (avoiding the use of sulfonylureas/glinides) and using certain basal insulin analogues in the case of insulin treatment (1⊕⊕⊕○).

- -

We suggest that the employer facilitate stable shifts, and allow glucose monitoring and CH intake during the working day, with the aim of preventing hypoglycaemia or treating it early should it occur (2⊕○○○).

- -

We suggest the application of the General Provision of the BOE 20/02/2019 (Spanish Official Gazette 20/02/2019) to the regulations of the Autonomous Regions in Spain so that diabetes ceases to be a cause of direct exclusion from offers of employment in the public sector, whether civil or military (2⊕⊕○○).

Incretins have granted DM2 patients access to activities they were previously excluded from: driving public transport such as trains, piloting planes, air traffic control and supervision of motorised traffic; weapons-related work; work with risk of falls (electrician, rooftop work). SGLT2 inhibitors are not yet included. Insulin treatment remains the limitation, despite the evidence on the new basal insulin analogues and on the use of CSII in reducing hypoglycaemia.

Diabetes has recently ceased to be a cause of direct exclusion from the entrance exams for civil servants and public employees in Spain, whether civilian or military, and these cases have to be assessed by a medical tribunal on an individual basis.

European Aviation Safety legislation maintains that DM with insulin means loss of or failure to obtain a licence for the position of air-traffic controller, pilot or cabin crew, adding incretins to metformin and alpha-glucosidases as permitted therapies in DM2, with medical checks to determine stability of blood glucose control.

Since 2010, driving licence validity is up to five years in DM1/DM2 with insulin for group 1, and one year in group 2. For licence renewals, having a favourable medical report that "certifies that the person concerned has adequate disease control and level of diabetes education" is mandatory.

Variable work shifts are discouraged "in insulin-dependent diabetics, although they can be adapted, with education and adjusting diet and insulin to work requirements".

Cognitive impairment and hypoglycaemiaRecommendations- -

We recommend considering that repeated and/or severe hypoglycaemic episodes are associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment in patients with DM (1⊕⊕⊕⊕).

- -

We recommend dietary and pharmacological strategies aimed at preventing hypoglycaemia in order to reduce the associated cognitive impairment (1⊕○○○).

Prolonged or severe hypoglycaemia can cause definitive cognitive changes. The mechanisms involved are multifactorial.10

In a retrospective study of 16,667 elderly people with diabetes, the risk of dementia increased by 26% (HR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.1–1.49) after a severe episode of hypoglycaemia, by 80% (HR: 1.80; 95% CI: 1.37–2.46) after a second episode and by 94% (HR: 1.94; 95% CI: 1.42–2.64) after three or more episodes. Several prospective studies have demonstrated the association between severe hypoglycaemia and dementia. It is a two-way relationship.

However, intervention studies, such as the Action Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD), have shown that intensification of blood glucose control increases the risk of hypoglycaemia, but have found no worsening of cognitive function. The ACCORD MIND MRI substudy found that severe hypoglycaemia was not associated with structural changes in the brain assessed by magnetic resonance imaging.

Please cite this article as: Reyes-García R, Mezquita-Raya P, Moreno-Pérez Ó, Muñoz-Torres M, Merino-Torres JF, Márquez Pardo R, et al. Resumen ejecutivo: Documento de posicionamiento: evaluación y manejo de la hipoglucemia en el paciente con diabetes mellitus 2020. Grupo de Trabajo de Diabetes Mellitus de la Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:270–276.