During pregnancy, thyroid function disorders are associated with multiple complications, both maternal and foetal. In recent years, numerous Clinical Practice Guidelines have been developed to facilitate the identification and correct management of thyroid disease in pregnant women. However, this proliferation of guidelines has led to confusion by proposing different cut-off points for reference values and different recommendations for similar situations. For this reason, the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición and the Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia have prepared this Consensus Document, with the aim of creating a framework for joint action to unify criteria for the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid dysfunction in these patients. The document is structured to answer the most frequently asked questions in clinical practice, grouped into five sections: 1/Reference values for thyroid function tests and screening during pregnancy 2/Iodine nutrition 3/Hypothyroidism and pregnancy 4/Hyperthyroidism and pregnancy 5/ Thyroid autoimmunity.

Durante la gestación, las alteraciones de la función tiroidea se asocian a múltiples complicaciones, tanto maternas como fetales. En los últimos años se han elaborado numerosas Guías de Práctica Clínica para facilitar la identificación y correcto manejo de la patología tiroidea en la gestante. Esta proliferación de guías ha causado confusión al proponer distintos puntos de corte de valores de normalidad y distintas recomendaciones ante situaciones similares. Por ello, la Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición y la Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia han elaborado el presente Documento de Consenso, con el objetivo de crear un marco de actuación conjunto que unifique criterios de diagnóstico y tratamiento de la disfunción tiroidea en estas pacientes. El Documento se estructura respondiendo a las preguntas más frecuentes que se plantean en la práctica clínica, agrupándose en cinco apartados: 1/Valores de referencia de pruebas de función tiroidea y cribado durante la gestación 2/Nutrición de Yodo 3/Hipotiroidismo y gestación 4/Hipertiroidismo y gestación 5/ Autoinmunidad tiroidea.

Thyroid function disorders are very common in women of childbearing age. Given their association during pregnancy with multiple complications, both maternal and fetal, various clinical practice guidelines have been developed to help in the identification and correct management of thyroid disease in pregnant women. Over the last decade, the leading scientific societies have developed different guidelines: the American Thyroid Association (ATA) 2011, the Endocrine Society 2012, the European Thyroid Association (ETA) 2014, ATA 20171 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2020. This proliferation of guidelines has contributed to increasing confusion by proposing different cut-off points for normal values and different recommendations in similar situations.

For this reason, the Boards of Directors of the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición (SEEN) [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition] and the Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia (SEGO) [Spanish Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics] have promoted the drafting of a common Consensus Statement, so that the doctors from both specialties have a joint framework of action, with the same criteria for the diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

Three experts were proposed for each specialty who designed a panel of 21 questions, grouped into five topics:

- -

Reference values of thyroid function tests, classification of dysfunctions and screening during pregnancy.

- -

Iodine nutrition.

- -

Hypothyroidism and pregnancy.

- -

Hyperthyroidism and pregnancy.

- -

Thyroid autoimmunity in pregnancy and postpartum.

The objective was to answer the questions posed through an eminently practical approach, trying to lay the foundations for a consensual therapeutic approach. The levels of evidence of the recommendations have been established following those of the previous clinical guidelines.

1Reference values, classification of dysfunctions and screening1.1What are normal values for thyroid function tests during pregnancy?According to the 2017 ATA guide, whenever possible, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) reference ranges should be defined based on the reference population and specific for each trimester. (Strong recommendation, moderate evidence.)1

If no own reference ranges are available, the ATA guideline places the upper limit of TSH in the first trimester at 4 mU/l.

1.2What is the right time to screen pregnant women for thyroid dysfunction?This cut-off point is valid when the TSH determination is performed between weeks seven and 12 of pregnancy. In Spain, given that the biochemical analysis of the programme for early detection of aneuploidy takes place at 9−11 weeks, the most practical recommendation is to unify both screening programmes (Table 1).

Outline of TSH reference values in the first trimester.

| WITH own reference ranges | WITHOUT own reference ranges |

|---|---|

| Prepared in EACH laboratory from a representative sample of: | Upper limit: 4.0 mU/la |

| Women without thyroid pathology | Lower limit: 0.1 mU/la |

| With good iodine nutrition | |

| Negative antithyroid antibodies | |

| They will be specific for each laboratory platform, depending on the brand of its reagents or technical specifications. | They can be used in any healthcare setting |

| Time performed: at 9−11 weeks, together with biochemical screening for aneuploidy |

The initial evaluation of thyroid function is performed by determining the level of TSH. The different possibilities of thyroid dysfunction are shown in Table 2.

Summary of the possible combinations that include thyroid dysfunction.

| TSH | T4 and/or T3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothyroidism | TSH > 95th percentile RR or | Clinicala | ↓ |

| TSH > 4 mU/l | Subclinical | Normal | |

| Hyperthyroidism | TSH < 5th percentile RR or | Clinical | ↑ |

| TSH < 0.1 mU/l | Subclinical | Normal |

RR: own reference ranges (adjusted for each population and trimester).

Other thyroid disorders:

- a)

Isolated maternal hypothyroxinaemia: decreased plasma levels of T4, with normal TSH. The most common cause in our setting is nutritional iodine deficiency.

- b)

Thyroid autoimmunity: presence of antithyroid antibodies (Ab), mainly anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) and anti-thyroglobulin. If positive, this implies a greater susceptibility to both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism and is associated with a worse reproductive prognosis.

There has been repeated debate on whether the screening of thyroid function during pregnancy should be performed universally (all pregnant women) or selectively (only in patients considered at risk).

At the SEEN-SEGO, we were pioneers in arguing in favour of universal screening for thyroid disease in the first trimester of pregnancy.2 The recommended screening strategies are listed in Table 3.

Screening strategies for thyroid dysfunction.

| Time performed | Test requested | Attitude to take | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy pregnant women | 9−11 weeks | TSH | – TSH > 10 mU/l: treat with levothyroxine (LT4)– TSH > 2.5: consider ordering an anti-TPO testa– TSH < 0.1: order a TRAb test and assess βhCG |

| High-risk obstetric patients: | |||

| – Previous infertility– Repeated miscarriages– Intrauterine death– Preterm labour | Ideally, pre-conception or at the time of confirming pregnancy (positive pregnancy test) | TSHFT4Anti-TPO | – If TPO is positive: treat with LT4 from TSH > 2.5 mU/l.– If TPO is negative: treat with LT4 from TSH > 4.0 mU/l |

| Patients with previous thyroid pathology: | |||

| Hypothyroidism | Ideally, pre-conception or at the time of confirming pregnancy (positive pregnancy test) | TSHFT4Anti-TPOb | Initially, increase the pre-conception dose of LT4 by 30% |

| Hyperthyroidism | Ideally, pre-conception or at the time of confirming pregnancy (positive pregnancy test) | TSHFT4, T3TRAbc | If active hyperthyroidism or in treatment before pregnancy, refer to Endocrinology– If TRAb positive: compatible with Graves' disease– If TRAb negative: consider other possible causes (toxic nodule, thyroiditis) |

Assess whether to order an anti-TPO test, especially in cases with a personal or family history of autoimmune disease.

Iodine is an essential micronutrient vital for the synthesis of thyroid hormones, and the nutritional needs are increased during pregnancy.3

The WHO's recommended iodine intake is 250 μg/day. Likewise, it establishes a threshold of 500 μg/day, above which no additional benefits are achieved and it could even induce alterations in thyroid function. On the other hand, the Institute of Medicine in the USA sets the needs at 220 μg/day during pregnancy and 290 μg/day during lactation.4

2.2Is its pharmacological supplementation recommended during pregnancy?Nutritional sources of iodine are:

- a)

Iodised salt: it constitutes the best dietary vehicle to guarantee an adequate intake of iodine.

- b)

Milk and dairy products: they are an emerging source of iodine intake, especially in school-age children.

- c)

Fish: although its iodine content may be high, it is considered insufficient to guarantee the daily requirements during pregnancy.

To provide 250 μg/day of iodine, three portions of milk or dairy products and 2 g of iodised salt should be consumed daily. It is necessary to initiate a pregnancy with adequate repletion of iodine stores, which requires consumption of iodised salt for at least two years prior to pregnancy.

Methods to ensure adequate iodine intake would be:

- a)

Foods rich in iodine: those referred to in the previous point.

- b)

Pharmacological supplements: they have an iodine content of between 150 and 300 μg per tablet and are marketed on their own or in combination with folic acid and vitamin B12. They are recommended when there is no guarantee of adequate iodine intake. (Strong recommendation, moderate evidence.)1

- c)

Multivitamin supplements containing iodine: although their iodine content in the data sheet ranges from 150 to 225 μg, their actual content is highly variable and not always adjusted to that indicated on the label.

When there is no certainty of adequate iodine intake, the use of potassium iodide supplements is recommended, which should be started pre-conception, at least two months beforehand, in order to achieve adequate iodine stores at the beginning of pregnancy and maintain them until the end of exclusive breastfeeding.

In cases of hyperthyroidism due to Graves-Basedow disease, it is advisable to suspend iodised salt and avoid iodine supplementation. The attitude towards a multinodular goitre is similar. Hypothyroid women should have an adequate intake of iodine, even if they are treated with levothyroxine.

2.3Is its pharmacological supplementation recommended during postpartum and lactation?The indication for maintaining pharmacological iodine supplements after childbirth will be conditioned by the type of breastfeeding:

- -

In mothers who opt for artificial breastfeeding, they are not necessary, since these formula milks already contain iodine.

- -

In cases of mixed breastfeeding (maternal-artificial) it will depend on the proportion of both. The more the mother breastfeeds, the greater the mother's iodine needs.

- -

In case of exclusive breastfeeding, iodinated supplements should be maintained throughout lactation.

Women with known hypothyroidism should plan their pregnancy to reduce the rate of complications. A TSH concentration of <2.5 mU/l is recommended. (Strong recommendation, moderate evidence.)1

Why is there a limit of 2.5 mU/l in pre-pregnancy hypothyroid women, when the cut-off point in euthyroid pregnant women is 4.0 mU/l? Because this ensures that the increased hormonal requirements of pregnancy can be met.

3.2How should pregnant women with clinical hypothyroidism be managed? (Including those diagnosed prior to pregnancy)Clinical hypothyroidism is associated with multiple maternal complications (miscarriage, anaemia, hypertension and pre-eclampsia, placental abruption, threat of preterm delivery, postpartum haemorrhage…) and fetal or neonatal complications (intrauterine death, low birth weight, neonatal respiratory distress…).5

The management of pregnant women with clinical hypothyroidism prior to pregnancy differs from that of those diagnosed during pregnancy and is shown in Table 4.

Management of clinical hypothyroidism.

| Clinical hypothyroidism TSH > 10 mU/l | TSH > 4 mU/l with low T4 | TSH > 95th percentile RR with low T4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Known before pregnancy | Diagnosed in pregnancy | ||

| Well controlled | Poorly controlled | ||

| In pre-conception | Avoid pregnancy until reaching TSH < 2.5 mU/l | No pre-conception controlTreatment non-compliers orPoor response to dose increase | There is not enough evidence to establish pre-conception thyroid dysfunction screening, except for women with a history of infertility |

| Started pregnancy | Thyroxine requirements increase from 4−6 weeks | Increasing the dose in women with uncontrolled hypothyroidism in the first trimester decreases the risk of fetal loss | Approximately 0.65% of theoretically healthy pregnant women have unknown clinical hypothyroidism, which can only be detected by screening |

| Premises | Although the ATA recommends increasing the dose of LT4 by 20−30% at the time of pregnancy confirmation, the dose increase will have a lot to do with the aetiology of hypothyroidism and with the pre-conception TSH levelPatients with a thyroidectomy or thyroid ablation will require higher doses than those with autoimmune hypothyroidism | There is no standard recommendation for this group of patients | The factors that determine the appropriate dose at the start are:Gestational age at diagnosisAetiology and severity of hypothyroidism |

| Plan | If before pregnancy TSH is between 2.5 and 4 mU/l or between 2.5 mU/l and 95th percentile RR, increase the dose of LT4 in:–Primary autoimmune hypothyroidism: Increase dose 25−30% (double dose 2 days per week)–Ablation hypothyroidism: Increase dose 40−45% (double dose 3 days per week)If before pregnancy TSH is between 5th percentile RR/<1.2 mU/L, do not modify the doseMonitor every 4 weeks until reaching TSH < 2.5 mU/l | Some authors propose doubling the usual LT4 dose 3 days a week (an increase of around 40%) and titration every 4 weeks until reaching TSH < 2.5 mU/l | Start with a calculated dose, at a rate of 2.3 µg/kg/day of LT4In patients with severe clinical hypothyroidism (TSH > 10 mU/l), a higher dose (up to double) than calculated may be administered at the beginning, in order to normalise the extrathyroidal store of thyroxine as soon as possible |

- -

It will be done by serial TSH testing. The first test should be done at the time the pregnancy is confirmed.

- -

Follow-up tests will be taken every four weeks. Shorter periods may induce overtreatment.

- -

Once the therapeutic goal of TSH < 2.5 mU/l has been reached, the TSH tests can be done every four weeks, until reaching week 20 and, at least once again before week 30. (Strong recommendation, high evidence.)1

- -

In the case of iron supplementation, due to its interference with LT4 absorption, a minimum separation of 4 h must be established between the intake of iron and of LT4.

- -

Confirm that LT4 intake is 30 min before breakfast to avoid decreased absorption. In case of frequent episodes of morning vomiting, recommend taking LT4 after each episode.

The association of subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) with maternal-fetal complications, and the recommendation or not of treatment, is highly controversial,6 as there is no clear evidence that intervention with LT4 can prevent adverse perinatal events.

Therefore, the recommendations for and against treatment should be applied on an individual basis, assessing the pros and cons of treatment. The different possible scenarios and treatment recommendations are listed in Table 5

Indications for treatment with levothyroxine (LT4) during pregnancy, taking into account the main outcomes (maternal and neonatal).

| Recommendation | For | Against | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal outcomes | |||

| Positive TPO | |||

| TSH > 10 mU/l | LT4 is strongly recommended | Treatment of clinical hypothyroidism reduces the risk of obstetric complications | None |

| TSH 4.0−10.0 mU/l | LT4 is recommended | Treatment of this group reduces complications and prevents progression to clinical hypothyroidism. | LT4 therapy should be monitored to avoid under/over treatment |

| TSH 2.5−4.0 mU/l | LT4 treatment may be considered | Treatment should be restricted to high-risk situations such as infertility or recurrent miscarriage (weak evidence for preterm birth) | Treatment recommendation is weakHigh risk of overtreatmentNo evidence of effectiveness for: gestational diabetes, hypertensive disease, or fetal growth restriction |

| TSH < 2.5 mU/l | LT4 is not recommended | Treatment should be restricted to high-risk situations such as infertility, assisted reproduction or recurrent miscarriage, and considered on an individual basis. | There is no evidence that LT4 treatment improves fertility rate and has not been shown to reduce the miscarriage rate in this group |

| Negative TPO | |||

| TSH > 10 mU/l | LT4 is strongly recommended | It is considered clinical hypothyroidism | The quality of the evidence is low |

| TSH 4.0−10.0 mU/l | LT4 is recommended | The risk is similar to that of SCH with positive TPO when TSH is 5−10 mU/l | Weak recommendationThe quality of the evidence is lowTreatment should be considered with caution in the absence of proper reference ranges |

| TSH 2.5−4.0 mU/l | LT4 treatment should not be used | Low doses of LT4 can be used in women undergoing IVF or ICSI, in order to achieve a TSH level <2.5 mU/l | There is no evidence that LT4 treatment improves fertility rate in euthyroid and anti-TPO-negative women |

| TSH < 2.5 mU/l | Treatment with LT4 is not recommended | None | Strong recommendation against the use of LT4 in this situationPotential risks of iatrogenic use of LT4 in pregnancy:–Growth restriction–Abnormal brain morphology in children |

| Cognitive function of offspring | |||

| TSH > 10 mU/l | LT4 is strongly recommended | High levels of untreated maternal TSH are associated with low intelligence quotient, independent of the test | The effectiveness of LT4 treatment is limited to early intervention (during the first trimester) |

| TSH 4.0−10.0 mU/l | LT4 is recommended | Early treatment with LT4 can improve cognitive function in offspring | The effectiveness of LT4 treatment has not been conclusively demonstrated in terms of cognitive outcomes |

| TSH 2.5−4.0 mU/l | LT4 treatment should not be used | None | High risk of overtreatmentNo evidence of effectiveness in cognitive outcomes |

| TSH < 2.5 mU/l | Treatment with LT4 is not recommended | None | Strong recommendation against the use of LT4 in this situationPotential risks of overtreatment with LT4 in pregnancy:–Fetal growth restriction–Abnormal brain morphology in children |

If deciding to treat SCH, it is recommended that treatment be started with 50 μg of LT4 in most cases.

Monitoring will be carried out by means of serial TSH testing, being indicated in all patients who:

- -

Receive replacement therapy with LT4.

- -

Are at risk of developing clinical hypothyroidism: previous hemithyroidectomy or patients with positive anti-TPO. (Strong recommendation, high evidence.)1

Women with properly treated clinical or subclinical hypothyroidism do not have an increase in obstetric complications, so there is no indication for additional studies. (Strong recommendation, moderate evidence.)1

3.4What would be the attitude after childbirth regarding the control and treatment of hypothyroidism?It is necessary to guarantee control of thyroid function after childbirth, for which we propose the Stagnaro-Green follow-up plan7 outlined in Table 6.

Treatment of postpartum hypothyroidism.

| Diagnosis | Postpartum recommendation | Postpartum testing |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical hypothyroidism | Two-thirds of the final LT4 dose reached in pregnancyIn the case of Hashimoto's thyroiditis, consider maintaining 20% more LT4 compared to the pre-gestational dose | 6 weeks |

| Subclinical hypothyroidismPositive antibodies | Half of the final LT4 dose reached in pregnancy | 6 weeks |

| Subclinical hypothyroidismNegative antibodies | If the last dose was: | |

| – 25 μg/day: discontinue | ||

| – 50 μg/day: reduce to 25 μg/day | 6 weeks | |

| – 75−100 μg/day: reduce to 50 μg/day | 6 weeks | |

| – >100 μg/day: reduce 25 μg each week until reaching 50 μg/day as final dose | Every 6 weeks until under control |

Maternal hypothyroxinaemia in the first trimester of pregnancy compromises the supply of thyroxine necessary for proper fetal neurological development. However, no published study has shown that LT4 treatment improves IQ in offspring. Given that, in our setting, the most common cause of maternal hypothyroxinaemia is nutritional iodine deficiency, we recommend early supplementation as the first measure of prevention against maternal hypothyroxinaemia.

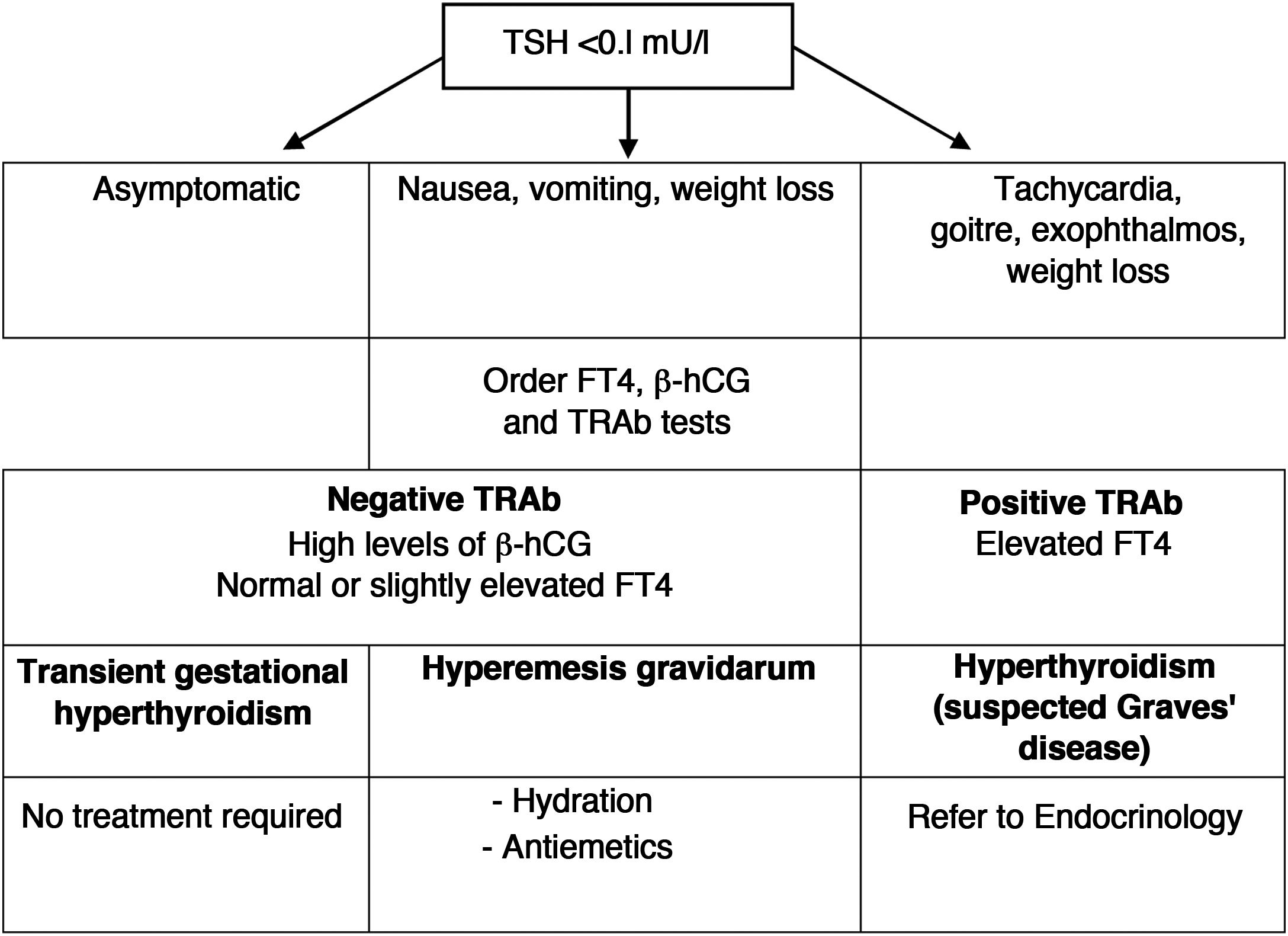

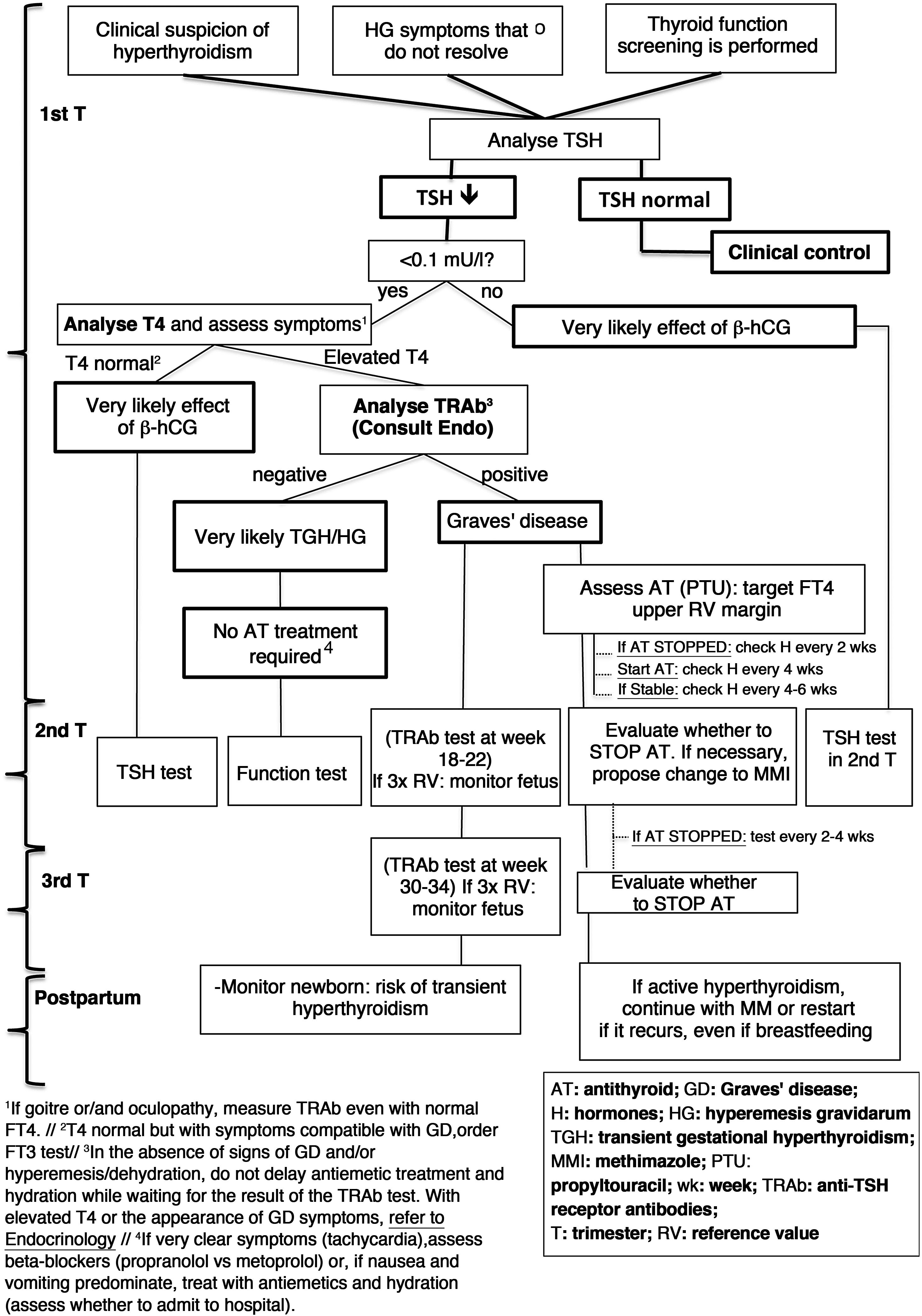

4Hyperthyroidism4.1How to distinguish hyperemesis gravidarum/transient gestational hyperthyroidism from Graves' disease?Nausea and vomiting are very common during the first trimester of pregnancy, but they are usually sporadic, of little relevance, and only a small percentage of women will develop hyperemesis gravidarum. Given that they present a low TSH, since its origin is related to a greater increase in ®-hCG, it must be distinguished from hyperthyroidism due to Graves' disease (GD). The clinical characteristics that help distinguish both conditions are listed in Table 7.

Differential diagnosis between gestational hyperthyroidism and Graves’ disease.

| Gestational hyperthyroidism | Graves' disease |

|---|---|

| Negative TRAb | Positive TRAb |

| Hyperemesis More common in multiple pregnancy | Frequently goitre and eye symptoms may be present |

| No symptoms before pregnancy | Probably already with symptoms before pregnancy |

| No family history of autoimmune disease | Family history of autoimmune disease |

| No need for antithyroid drugs | Need for antithyroid treatment |

| Usually self-limited from the second trimester | Variable clinical course, although it usually improves during pregnancy |

Transient gestational hyperthyroidism is more common in patients with high titres of ®-hCG (multiple pregnancy, assisted reproduction techniques, primigravida, etc.). It is not usually accompanied by any symptoms, and does not require treatment or additional thyroid function tests. The analytical alteration is self-limited when ®-hCG titres fall, starting in the second trimester.

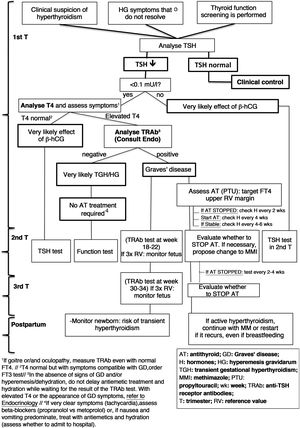

In the case of hyperemesis gravidarum, treatment should include hydration, electrolyte replacement and the use of antiemetic drugs. A diagram of the differential diagnosis and clinical management of low TSH in the first trimester is shown in Fig. 1.

4.3How is hyperthyroidism due to Graves' disease managed during pregnancy?Hyperthyroidism due to GD represents a situation of high obstetric risk:

- -

Patients most commonly present both maternal (pre-eclampsia, heart failure) and fetal (placental abruption, fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism) complications.

- -

The use of antithyroid drugs can have teratogenic effects.

The general principles of treatment of hyperthyroidism are8:

- -

When antithyroid treatment is indicated, it should be used with the lowest possible dose of drug that allows T4L levels to be maintained in the upper limit of normal. (Strong recommendation, very high evidence.)1

- -

The drug of choice in the first trimester is propylthiouracil. Subsequently, it is preferable to switch to methimazole due to the risk of hepatotoxicity of propylthiouracil.

- -

The maximum recommended daily dose for propylthiouracil is 200−400 mg and for methimazole it is 10−20 mg.

- -

Antithyroid drugs have been associated with a long list of birth defects. Therefore, withdrawal should be considered in women wanting to become pregnant or at the beginning of pregnancy, especially if anti-TSH receptor antibodies (TRAb) are low or undetectable, and when low doses are used.

- -

Thyroid function should be evaluated every four weeks, and treatment adjusted accordingly. (Strong recommendation, high evidence.)1

- -

Subclinical hyperthyroidism does not require treatment as it is not associated with greater obstetric or fetal morbidity.

A diagram of the diagnosis and treatment of hyperthyroidism due to GD is shown in Fig. 2.

Diagnosis and management of hyperthyroidism during pregnancy (based on Alexander et al.1).

Both TRAb present in the maternal circulation and antithyroid drugs can cross the placenta, so the fetus can have both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism.

Women who have undergone definitive treatment for GD may maintain high titres of circulating TRAb, so there is a risk of fetal hyperthyroidism in the absence of hyperthyroidism in the mother.

4.4.1TRAb tests during pregnancyThe control and follow-up of TRAb according to their concentration and trimester of pregnancy is shown in Table 8.

Control of TRAb plasma levels during pregnancy.

| Trimester | TRAb levels | Action |

|---|---|---|

| First | They are low or undetectable | Very low risk of fetal hyperthyroidism |

| If FT4 normalised, consider reducing or suspending AT. No further TRAb tests required | ||

| They are elevated | If FT4 also elevated, increase AT. Perform a new test at week 18−22 | |

| Second | They become negative | If FT4 normalised, consider reducing or suspending AT |

| Monthly monitoring of thyroid function | ||

| They continue to be elevated | If FT4 also elevated, increase AT | |

| Perform a new test at week 30−34 | ||

| They are 3 times the upper limit of the reference value | If FT4 also elevated, increase ATMonitor fetus from week 20−22 (high risk of fetal hyperthyroidism) | |

| Third | They are 3 times the upper limit of the reference value | Ultrasound monitoring of the fetus (high risk of fetal hyperthyroidism) |

| Newborn monitoring (very high risk of neonatal hyperthyroidism) |

AT: antithyroid.

If in the second or third trimesters TRAb levels are three times the reference value, there is a high risk of fetal hyperthyroidism, requiring ultrasound monitoring.

4.4.2Neonatal management of the child of a mother with Graves' diseaseWhenever there is a history of maternal thyroid disease, use of antithyroid drugs during pregnancy, or positive TRAb, this information should be reported to the newborn's neonatologist or paediatrician. (Strong recommendation, moderate evidence.)1

TRAb should be measured in cord blood or as soon as possible after delivery. In newborns with positive TRAb in cord blood, it is recommended to perform a thyroid function study on days 3–5 of life.

4.5How is Graves' disease managed postpartum and during lactation?There is a risk of reactivation of GD in the mother after delivery, especially between 4–12 months postpartum. In case of reactivation, the drug of choice is methimazole.

The level of antithyroid drugs passing into breast milk is very low and does not contraindicate breastfeeding. Thyroid function monitoring is not recommended in these infants. (Weak recommendation, moderate evidence.)1

4.6Pregnancy desire and hyperthyroidism: a contraindication?It is not an absolute contraindication, but the difficulty of managing hyperthyroidism during pregnancy and the risk it poses to the fetus and the newborn make it inadvisable, at least until the hyperthyroid situation is controlled.1 The recommended attitudes in these different situations are listed in Table 9.

Possible scenarios in cases with a history of hyperthyroidism due to Graves' disease with pregnancy desire.

| In pre-pregnancy | Controlled hyperthyroidism | Uncontrolled hyperthyroidism |

|---|---|---|

| Patient profile | Patients in remission who do not require treatment or who have been stable with antithyroid treatment (MMI/PTU) for at least 2 months | Patients who have poor control despite antithyroid treatment or who require very high doses of antithyroid drugs |

| Laboratory findings | TSH, FT4 and FT3 in normal or minimally altered ranges | TSH very low |

| Elevated FT4 and/or FT3 | ||

| TRAb negative or with low titres | TRAb at high titres | |

| Attitude to take | Confirm euthyroidism at 2 months | Establish contraceptive method |

| Adjust treatment: | ||

| If taking MMI, consider changing to PTU | ||

| Increase dose until euthyroidism is achieved | ||

| Recommendation | Pregnancy can be planned | Pregnancy is not recommended |

| Assess whether to withdraw antithyroid treatment before pregnancy or replace MMI with PTU | If very high doses of antithyroid drugs are required, evaluate definitive treatment (thyroidectomy or ablation with 131I) | |

| In case of pregnancy | Assess whether to withdraw treatment in the first trimester. In case of treatment, replace MMI with PTU | High risk pregnancy |

| Maintain strict monitoring in the event of a possible exacerbation (request TSH, T4, T3 and TRAb tests at the time the pregnancy is confirmed.) | Immediately switch treatment from MMI to PTU | |

| Iodine supplementation is not recommended | Closely monitor the fetus for: risk of congenital anomalies associated with antithyroid drugs and for risk of fetal hypo/hyperthyroidism | |

| Iodine supplementation is not recommended |

MMI: methimazole; PTU: propylthiouracil.

It has been considered that the presence of thyroid autoimmunity is an independent risk factor for miscarriage,9 and there is debate about whether euthyroid pregnant women with positive anti-TPO should be treated with LT4. Table 5 summarises the possible options.

5.1.2Thyroid autoimmunity and preterm birthThe association between thyroid autoimmunity and risk of preterm birth has been evidenced in different meta-analyses. However, the ATA guideline considers that there is not enough evidence to recommend treating euthyroid pregnant women with positive anti-TPO with LT4 to prevent preterm delivery. (No recommendation, insufficient evidence.)1

5.2In what situations is an anti-TPO Ab test recommended?In pregnant women, an anti-TPO Ab test is recommended when TSH is greater than 2.5 mU/l at the beginning of pregnancy.1

Antithyroglobulin Abs are becoming increasingly important as a cause of infertility/subfertility.10 For this reason, it is recommended that they be measured in women who consult for infertility. (Strong recommendation, moderate evidence.)10

5.3When to suspect postpartum thyroiditis and how is it controlled?Postpartum thyroiditis (PPT) is the appearance of an autoimmune thyroid disease in the first year postpartum. Its prevalence is around 5%.

Risk factors for its appearance are the presence of thyroid autoimmunity or other autoimmune diseases, as well as a previous history of PPT.

5.3.1Presentation of postpartum thyroiditisThe clinical form of presentation is variable:

- -

Classic: Transient phase of hyperthyroidism, followed by transient phase of hypothyroidism, with return to euthyroidism by the end of the first postpartum year. It accounts for about 20% of the different forms of PPT.

- -

Isolated hyperthyroiditis: Symptoms of thyrotoxicosis, which require differential diagnosis with GD It accounts for about 30% of the different forms of PPT.

- -

Isolated hypothyroiditis: Almost half of PPTs present as hypothyroidism, which appears 3–8 months postpartum. In a significant percentage of cases (10–50%), hypothyroidism will be permanent.

- -

During the thyrotoxic phase of PPT, symptomatic women can be treated with beta-blockers safe for breastfeeding, such as propranolol or metoprolol, at the lowest dose that relieves symptoms. (Strong recommendation, moderate evidence.)1

- -

LT4 treatment should be considered in symptomatic women in the hypothyroid phase of PPT. If treatment is not started, assessment of TSH levels should be repeated every 4–8 weeks until thyroid function returns to normal. LT4 treatment should also be started if the woman is trying to become pregnant or is lactating. (Weak recommendation, moderate evidence.)1

- -

If treatment with LT4 is started, its suspension should be attempted after 6–12 months. Dose reductions should be avoided if the woman wants to become pregnant or is pregnant. (Weak recommendation, low evidence.)1

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors wish to thank Drs Elena Navarro, Juan Carlos Galofré, Mercè Albareda and Piedad Santiago for their contribution in reviewing this manuscript.

The full Consensus Statement is available at: https://www.seen.es/ModulGEX/workspace/publico/modulos/web/docs/apartados/3356/100322_120046_3574428481.pdf.