Achieving an optimal glycaemic control without hypoglycaemia is the main treatment objective for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D). Over the last years, improvements in diabetes education, intensified insulin therapy, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) have supported people with T1D to achieve this goal. In spite of all these advances, still barriers exist to obtain an ideal control in the majority of patients.

Continuous intraperitoneal insulin (CIPII) administration may be considered as a treatment modality for both adults and children with T1D using optimised intensive insulin therapy for whom subcutaneous insulin has failed due to subcutaneous insulin resistance or skin conditions (lipoatrophy/hypertrophy, skin reaction or local allergy). Failure of subcutaneous insulin may result in recurrent or unexplained hypoglycaemia or hyperglycaemia.1 It has also been considered as a treatment modality for adults with T1D with severe needle phobia, and for those being considered for islet cell/pancreatic transplantation, or where transplantation is not available. It has been reported than CIPII has comparable glucose outcomes with less hypoglycaemia and less insulin dose than the obtained by CSII.2–4

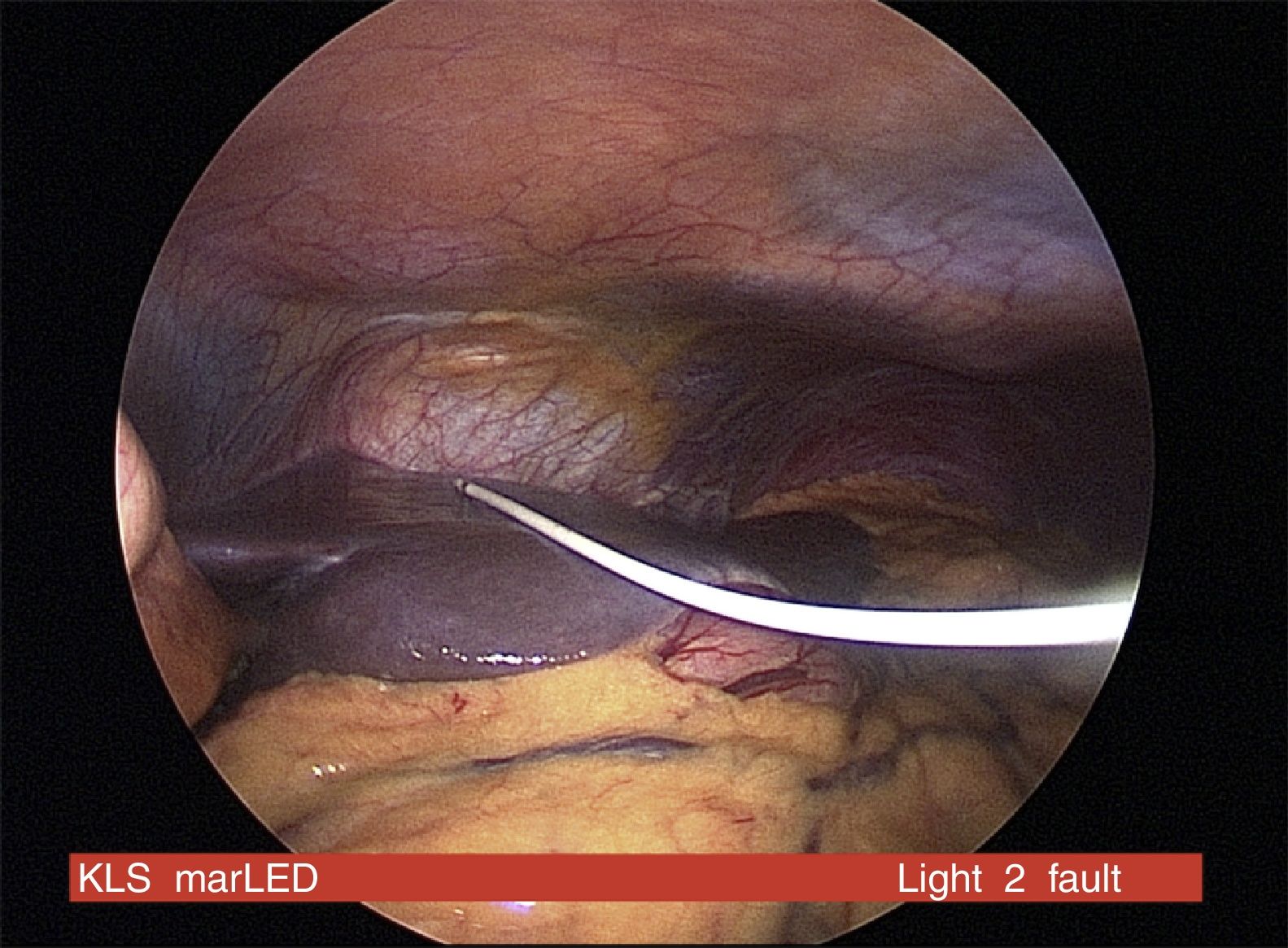

There are two different technologies developed in CIPII: implanted intraperitoneal pumps (MiniMed MIP2007C, Medtronic, Northidge, USA) and implanted catheter as the DiaPort system (Roche Diabetes, Germany). CIPII pumps are implanted surgically over the rectus abdominus muscle fascia and contains a reservoir that can be filled every 6 weeks with U400 insulin and a catheter extended into the peritoneal space. On the other hand, the DiaPort system consists of a surgically established intraperitoneal catheter connected to a percutaneous port implanted in the anterior abdominal wall. In this case, the Roche Accu-Chek Combo pump (Roche Diagnosis, Basilea, Switzerland) filled by U100 human insulin is connected to the port and operates as it was a CSII pump.5,6

Here we present data from a 52-year-old man with T1D diagnosed in 1974 at the age of 11. He started treatment with CSII (Accu-Chek Combo) in 2013 because of repeated severe/non severe hypoglycaemia/hypoglycaemia unawareness at Charing Cross Hospital, London. At the same time, CGM through a Dexcom G4 platinum (Dexcom, CA, USA) system was started. In 2014, he presented active retinopathy with recurrent photocoagulation due to continuous proliferative changes. His HbA1c was 48mmol/mol (6.5%) and his creatinine was 84μmol/L. The same year, he started developing problems with subcutaneous insulin absorption. It was reported that delivered insulin was not acting appropriately with a delayed insulin absorption and late episodes of hypoglycaemia.

An individualised programme for optimising his glycaemic control was then started. Structured education revised, insulin use checked and the patient was closely monitored to improve his metabolic control. Addison's disease, presence of autoantibodies against insulin and other endocrinopathies were excluded during the study. Finally, different types of insulin, injection sites and cannulae were tried to solve the situation.

A subcutaneous insulin absorption test was performed in order to complete the study. All subcutaneous insulin was stopped at midnight. IV aspart insulin was administered in a sliding scale overnight. During the morning, IV insulin was stopped to give a subcutaneous bolus of 0.3UI/kg of insulin aspart. Glucose (mmol/L) and insulin (mu/L) were measured at times −60, 0, 30, 60 and 90min. C-peptide was undetectable (<3pmol/L). Measurements of glucose/insulin were 11.0/14.1, 11.8/68.7, 10.4/75.1 and 8.9/78.6 at 0, 30, 60 and 90min respectively. The test was considered abnormal as the glucose lowering was delayed to 90min with serum insulin still rising.

The presence of active microvascular complications, hypoglycaemia unawareness, insulin requirements >0.8UI/kg/24h, variable insulin absorption, significant psychological impact and being on an intensified regimen supported by technology forced the team to rethink his treatment.

The clinical team finally decided to proceed for individual funding approval for DiaPort CIPII system. Human insulin U100 in combination with a stabilising agent was chosen instead of rapid acting insulin analogues as they are not suitable for CIPII because have been associated with catheter occlusion. CGM through Dexcom G4 platinum was continuously used before and after the procedure. During the 2-years follow-up there were neither severe hypoglycaemia nor ketosis/ketoacidosis episodes presented. Retinopathy remained stable and hypoglycaemia awareness was not completely restored. Two catheters replacements due to blockage were performed during the follow-up.

CIPII devices require a surgical procedure for insertion with associated risks of the anaesthesia, bleeding, infection and discomfort (Fig. 1). The commonest complications of CIPII use are catheter occlusion, pump dysfunction, pain and local infection. However, 80% of people using CIPII had no reported complications over a 15-month period. Peritonitis is rare (0.4/100 patient year) and no mortality related to peritonitis has been reported with CIPII.7 In a prospective randomised trial using CIPII through catheter, the more frequently reported adverse event was infection/inflammation around the port affecting 21%/10% of the patients after 6/12-months of follow-up, respectively. The median time from implantation to the occurrence of the first complication requiring surgical intervention was 3.6 years (95%CI: 2.2–5.0 years).8

The cost between both CIPII techniques differ substantially. While DiaPort implantation kit cost is around €5000 excluding the costs of insulin and surgical implantation, the cost for an implantable pump is close to €30000 with an expected battery life of 8 years (the cost of additional visits for pump reservoir filling and U400 insulin are not included).9

CIPII seems to be a valuable option for people with T1D who are unable to safely or effectively manage their diabetes with subcutaneous insulin due to skin issues. Until now, it has been also a good choice for those people with T1D and severe hypoglycaemia, and for whom transplantation options were either unavailable or unsuitable.10 Moreover, given the reversible nature of CIPII and its comparatively low risks and costs when compared with transplantation, it may be a treatment modality to consider as an alternative to islet cell/pancreas transplantation. Nevertheless, as new technological options appear on the market (like sensor-augmented pump with low/predictive suspend or hybrid closed-loop systems) it is difficult to value the paper that CIPII is going to have in the next future. In this scenario, it is very likely that it will eventually only become an alternative for those with skin problems or extreme insulin resistance.